Abstract

Mycoparasites cause heavy losses in commercial mushroom farms worldwide. The negative impact of fungal diseases such as dry bubble (Lecanicillium fungicola), cobweb (Cladobotryum spp.), wet bubble (Mycogone perniciosa), and green mold (Trichoderma spp.) constrains yield and harvest quality while reducing the cropping surface or damaging basidiomes. Currently, in order to fight fungal diseases, preventive measurements consist of applying intensive cleaning during cropping and by the end of the crop cycle, together with the application of selective active substances with proved fungicidal action. Notwithstanding the foregoing, the redundant application of the same fungicides has been conducted to the occurrence of resistant strains, hence, reviewing reported evidence of resistance occurrence and introducing unconventional treatments is worthy to pave the way towards the design of integrated disease management (IDM) programs. This work reviews aspects concerning chemical control, reduced sensitivity to fungicides, and additional control methods, including genomic resources for data mining, to cope with mycoparasites in the mushroom industry.

1. Introduction

Mushrooms are worldwide cultivated and consumed. In 2013, the global edible mushroom industry size was valued at 34 B € [1]. The cultivated mushroom industry, in line with the vegetable and fruit production industry, is subjected to increasing pressure for a change in the productive systems. A consumer-driven shift is claiming for healthier products with an environmentally respectful background to cut down dependence on chemical fungicides. Cultivated mushrooms are grown indoors under controlled environmental conditions that facilitate the implementation of integrated disease management programs, combining chemical fungicides, biocontrol alternatives, and correct agronomical management (the choice of casing and moisture level, the disinfection method, and management at the time of infection) to prevent outbreaks and disease dispersion [2,3,4].

Fungal diseases are among the most serious disorders of mushroom crops, damaging yield and mushroom quality [2,5]. The preventive use of phytosanitary products is routinely applied on top of the casing layer, although multiple evidence of resistance has been reported from the second half of the 20th century to different fungicide groups such as dithiocarbamates (multisite activity) [6], methylbenzimidazole carbamates (MBC) (targeting mitosis and cell division, inhibitor of spindle microtubules assembly) [7,8,9,10,11] or demethylation inhibitors (DMI-fungicides) (inhibitor of sterol biosynthesis in fungal cells) [12,13]. However, some alternative fungicides such as metrafenone (benzophenone) (whose mode of action targets cytoskeleton and motor protein; actin/myosin/fibrin function), introduced in the mushroom industry by the mid-2010s, showed promising results [14,15,16]. The continued use of the same active substances to fight fungal parasites of mushroom crops can prompt the onset of resistant strains [10,17]. Prior to allowing new fungicides, the effect on commercial host strains must be studied both in vitro and in vivo before approval to prevent crop damage [18]. Since both mycoparasite and host are fungi, proven selectivity is the key aspect for suitable fungicides, which restricts the emergence of alternative chemicals [19].

Although some evidence of a defensive response of mushrooms to the attack of fungal parasites has been studied, such as the noted increasing production of laccase to fight green mold [20], the immune response of mushrooms to mycoparasite action still remains broadly unresolved [5], which represents a shortcut to design resistant strains through breeding programs [21]. Likewise, mechanisms of host–microorganism interaction are still mostly unknown. However, different genomic resources, including the release of host [22] and some mycoparasite genomes [23,24,25,26], have been disclosed within recent years. The knowledge available can, for instance, serve as a tool for mapping quantitative trait loci (QTL) of mycoparasite-resistant genes in the mushroom host through data mining [27,28].

The present work reviews the four most harmful fungal diseases in cultivated mushrooms: dry bubble disease (DBD), cobweb, wet bubble disease (WBD), and green mold, including reported symptoms and causal agents, chemical control, and resistant evidence to eventually introduce proved alternative control methods in the form of bio-based product application and active biocontrol agents. Ultimately, recently released genomic resources are reviewed and discussed as a tool to design strategies for breeding programs to produce resistant strains. Besides, the authors compile a guide of good practices to cope with fungal diseases by means of intensive hygiene and crop management.

2. Dry Bubble (Lecanicillium fungicola)

2.1. Causative Agent and Symptoms of Disease

The causative agent of dry bubble (DBD) in mushroom crops [29] is associated with two varieties of the species Lecanicillium fungicola, var. fungicola and var. aleophilum, historically described as Verticillium fungicola [30]. Dry bubble is a ubiquitous fungal disease reported occurring in different countries cropping edible mushrooms [31,32,33,34], parasitizing various cultivated mushroom hosts such as Pleurotus ostreatus, Agaricus bitorquis, and Agaricus bisporus [29,35,36]. DBD accounts for an estimated 20% of button mushroom crop losses globally [37], which for the European sector represents losses of approximately 300 M€ annually. The ascomycete L. fungicola (Figure 1a) is an asexual organism that has been detected by metataxonomic analysis to be present in the compost and casing used in mushroom cultivation even in asymptomatic crops [32]. It is remarkable that symptoms of the disease have not been reported to occur in the colonized compost (Phase III) before applying the casing material on top. Therefore, first symptoms are reported to occur in the casing material, rarely prior to the harvest when the induction to fructification is promoted by means of environmental cues [38]. Primary infection drives to undifferentiated masses of infected host tissue known as bubbles. Likewise, other symptoms such as stipe blow-up (distorted and broken stipes of fully developed mushrooms) (Figure 1a), spotting, and sunken lesions in the caps generate serious yield losses [2].

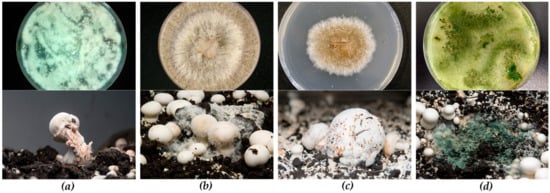

Figure 1.

Mycoparasite plated on potato dextrose agar (PDA) (top pictures) and disease symptoms in Agaricus bisporus commercial crops (bottom pictures): (a) Lecanicillium fungicola/dry bubble disease (DBD); (b) Cladobotryum spp./cobweb disease; (c) Mycogone perniciosa/wet bubble disease (WBD); (d) Trichoderma spp./green mold disease.

The vegetative mycelium (net of hyphae colonizing the compost and the casing before fructification) has been proved resistant to L. fungicola [29]. The infected host tissue (reproductive morphological stage, mushroom tissue) is covered by the parasite which produces spherical masses (clusters) of conidia covered by sticky mucilage that favors the disease dispersion through watering, fly vectors (phorid and sciarid flies), workers, or dirty machinery [30,38]. The air powered through ventilation systems can also play an important role in disseminating DBD inside the mushroom farm or even transporting it to nearby installations. The main primary source of L. fungicola mentioned in mushroom crops is the casing material and, especially, peat [39]. Besides, infected mushrooms, phorid flies, and contaminated equipment can also play an important role as a primary source of infection [40].

2.2. Chemical Control and Resistance

The severity of the damage caused by DBD has led to applying several control measures against its causative agent. These preventive measures refer to the application of fungicides, control through the implementation of efficient cultural practices, sanitation, and attempts on the application of biological control.

In respect to the preventive fungicides applied to cope with DBD, the emergence of active substances from the group of methyl benzimidazole carbamates (MBC) in the late 1960s enabled efficient control of different fungal diseases affecting mushroom crops, including DBD as a major concern [41,42,43]. However, the continuous application of the same fungicides was quickly conducted to reduce sensitive and resistant L. fungicola strains, in addition to cross-resistance among MBC fungicides [7,8]. Bonnen and Hopkins [44], when evaluating fungicide response against isolates of L. fungicola, collected over a period of 45 yr, detected cross-resistance between benomyl and thiabendazole, negative cross-resistance between these two benzimidazole fungicides and the carbamate fungicide diethofencarb, and relatively high resistance towards chlorothalonil (chloronitrile, whose mechanism of action reduces and thereby deactivates glutathione). Evidence of resistance to the widely used benzimidazole and ergosterol demethylation inhibiting fungicides, including benomyl (ED50 = 415.45–748.12 mg L−1), carbendazim (ED50 = 1123.87–1879.59 mg L−1), and iprodione+carbendazim (ED50 = 415.45–748.12 mg L−1) have been also reported among Iranian strains isolated from diseased button mushrooms [31]. Besides, moderately reduced sensitivity to iprodione was noted among Serbian L. fungicola isolates [45], and resistant isolates to this active substance were also reported in Spain [46].

Prochloraz-Mn, currently approved imidazole fungicide to fight DBD in European mushroom crops, was introduced in 1983 to treat varieties of Lecanicillium fungicola resistant to benzimidazoles, WBD, and cobweb [47]. Likewise, evidence of reduced sensitivity to prochloraz-Mn with isolates showing ED50 values of 16.17 mg L−1 has been reported among Iranian strains [31]. In a major analysis of dose–response confronting L. fungicola to prochloraz-Mn, 105 isolates of L. fungicola from Spanish button mushroom crops collected between 1992–1999 were tested in vitro. L. fungicola sensitivity to prochloraz-Mn gradually diminished among newer isolates and moderately resistant strains were noted among the newest strains under study [13].

2.3. Alternative Control and Breeding

The number of biocontrol agents available to cope with mycoparasites of mushroom crops is still limited in the market [4,48]. However, currently, a fluent scientific activity aims to generate alternatives for the overused and, in some cases, relatively low-efficient chemical pesticides. Table 1 reviews alternative bio-based formulations reported within the last 15 years to fight mycoparasites (L. fungicola, M. perniciosa, Cladobotryum spp., and Trichoderma spp.) of cultivated mushrooms.

Table 1.

Alternative bio-based formulations employed to fight mycoparasites of cultivated mushrooms: EOs from botanicals, plant extracts, and compost teas (last 15 years).

Among them, aqueous extracts obtain from diverse biological matrixes have proved efficient to treat DBD in crop trials and to avoid parasite germination and mycelial growth in vitro. Aqueous extracts obtained from composted bio-waste materials, known as compost teas (CT), exhibit antifungal properties to control plant pathogens [72]. Aerated and non-aerated compost teas obtained from spent mushroom compost (SMC), grape marc compost (GMC), crop residues compost (CRC), and crop residues vermicompost (CRV) provided significant in vitro suppression of L. fungicola [53]. In further work, the authors reported that the microbial community of these compost teas is the main factor responsible for the antagonistic effect against mycoparasites [73], which is in accordance with the state-of-the-art [74]. The selective suppressive effect noted in teas from SMC towards the mycoparasites could be related to the selectivity of mushroom compost for the growth of A. bisporus, which means that the native microbiota inhabiting this environmental niche is innocuous for the host while exhibiting fungitoxicity against the mycoparasites. After the evaluation of 16S rDNA-based denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) profiles (a technique used to separate DNA fragments by length based on their melting characteristics), they showed higher bacterial richness, diversity, and evenness values in aerated compared to non-aerated compost teas and noted high levels of siderophore (low-molecular-weight high-affinity iron-chelating compounds secreted by microorganisms that serve as iron carrier across cell reducing the availability of iron, an essential micronutrient for the mycoparasite) production in teas from CRC and CRV, high and consistent cellulase activity in teas from GMC and high protease activity in all the aerated compost teas under study, especially SMC [73]. Application of compost teas has been reported as innocuous for button mushroom crops since their application had no significant deleterious effect on the quantitative production parameters for the crop (yield, unitary weight, biological efficiency, and crop earliness) and compost teas incorporated into growth media in vitro was not fungitoxic for the host [75]. Therefore, the fungitoxic effect observed in vitro against L. fungicola and the results achieved showing a better response of aerated compost tea from SMC in comparison to prochloraz-Mn to prevent dry bubble disease in crop trials [54] suggest that the application of compost teas could be a suitable alternative to common fungicides. In addition to compost teas, EOs from aromatic plants have also shown fungitoxic effect in plate (cinnamon, thyme, and clove oils were the most effective in inhibiting the mycelial growth and conidia germination of L. fungicola) and effectiveness in crop applications (particularly effective in application after infestation) [56]. However, the selectivity of EOs towards the parasite is reduced and all the EOs tested by Geösel et al. [76] caused damage in the crop, inhibiting the growth of host mycelium and causing necrotic spots on mushroom caps. In this respect, selectivity trials must be conducted in addition to toxicity tests for the selection of more efficient products. Mehrparvar et al. [31] when evaluating the antifungal activity of eleven EOs against L. fungicola and A. bisporus noted different selectivity values (associated with the singular enzymatic pathways of the parasite and the host), highlighting the EOs of Zataria multiflora (main components thymol and carvacrol) and Satureja hortensis (main component carvacrol) as the most selective.

The mechanism of host–pathogen interaction driving mycoparasitism of mushroom crops is still unknown, which is a limitation to develop breeding programs aimed to leverage host varieties resistant to fungal parasites. Zied et al. [77] reported different degrees of tolerance to the pathogen among 15 commercial strains of A. bisporus assayed in crop trials. The comparison of sensitive and resistant host strains can facilitate the identification of candidate genes involved in defensive response and also identify promoters suitable to ensure specificity of expression. The commercial white button mushroom line of A. bisporus has been proved to express specific genes differentially after infection [78]. DBD symptoms related to cap spotting can be a result of secondary metabolites produced by the parasite during conidia germination. The recently released genome of L. fungicola strain 150-1 (GenBank Ac. No. FWCC00000000) (Table 2) revealed 38 biosynthetic gene clusters for secondary metabolites including 8 PKSs (PolyKetide Synthases), 21 NRPS (Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases) or NRPS-like clusters, 3 PKS-NRPS hybrids, 5 terpene synthases, and 1 indole cluster [23]. Further investigation and data mining can contribute to design programs for classical breeding and genetic modification with the aim of generating resistant varieties.

Table 2.

Genome features of host strain and mycoparasites were recently released as a source of information for breeding programs.

3. Cobweb Disease (Cladobotryum spp.)

3.1. Causative Agent and Symptoms of Disease

Cobweb is a globally widespread pathology whose causative agent corresponds with several Ascomycota species described as harmful in different mushroom-producing countries and all belonging to the genera Cladobotryum spp. Among them, C. dendroides [26], C. mycophilum [79], C. protrusum [25], or C. varium [80] have been described as parasites of cultivated mushrooms but also infecting mushrooms in the wild [81]. Cladobotryum spp. is a versatile parasite with a broad host range; among the reported cultivated species susceptible to cobweb are button mushrooms (Agaricus spp.), oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus spp.), shiitake (Lentinula edodes), beech mushroom (Hypsizigus marmoreus), winter mushroom (Flammulina velutipes) or reishi (Ganoderma spp.) [80,82,83,84,85,86,87]. The taxonomy and morphological features associated with the different parasites have been thoroughly described [88]. The prevalence of cobweb disease in commercial mushroom crops has been reported to vary between 6.8-33% in India, Turkey, or Spain [85]. Heavy losses up to 40% were noted when the disease reached epidemic proportions in the UK and Ireland in the mid-1990s [89].

Symptoms of the disease include the initial development of aerial and light-whitish mycelium over the casing layer and infected carpophores (Figure 1b) that quickly evolves due to massive sporulation to a dense white-floury mass that engulfs the surface of the casing layer and the surrounding carpophores; therefore, reducing the crop area available [86,87,88]. It is also worth noting that due to the nature of the dry spores generated by Cladobotryum (Figure 1b), they are easy to disturb from the patches of disease during cropping operations such as watering or picking, or even by low air currents in the growing facility [89]. When conidia land on mushroom caps, they generate spots that makes the crop unsalable, ending in significant losses [2,88].

Cobweb appears more often at the end of the crop cycle (although the earlier it appears, the more devastating it can be), commonly during autumn and winter cycles [86]. Under unfavorable conditions, particularly when the relative humidity (RH) is low, most Cladobotryum spores do not survive for long periods. However, the fungus produces microsclerotia, resistant structures that can germinate even when they are stored at 0% RH [90]. High humidity conditions outside the cropping rooms will facilitate the survival of the pathogenic conidia and their dispersal throughout the production area [88,91].

It is also worth noting that due to the nature of the dry spores generated by Cladobotryum (Figure 1b), they are easy to disturb from the patches of disease during cropping operations such as watering or picking, or even by low air currents in the growing facility. A single conidium or mycelium debris mobilized from the initial infection can generate a new secondary outbreak because of their asexual nature. Since mushroom cultivation is produced in localized areas with a high density of growers, the initial source of the disease has been associated with external contamination of mushroom substrates through airborne conidia from nearby aged crops [88] or even specimens infected in the wild [92].

3.2. Chemical Control and Resistance

To prevent disease outbreaks, complex hygiene procedures are introduced during the transport of cultivation inputs (substrates, casing materials) and at the growing facilities as detailed in Section 6 [2,93]. However, still, many growers have no adequate means of controlling mushroom diseases such as cobweb and thus the risk of disease occurrence is extremely high. To tackle disease occurrence, chemical products are often applied as preventive treatments for extensive outbreaks. Despite different families of active substances have been historically applied including prochloraz-Mn (DMI-fungicides), metrafenone (benzophenone), chlorothalonil (chloronitrile), or thiabendazole (MBC-fungicide), in the last years the license of some broadly applied active substances are not renewed, for instance, recently the EU Member States voted to ban chlorothalonil [94], and the expected scenario suggests increasingly restrictive legislation. The scarce range of available products in addition to the continuous exposure to the same active substances has also favored the occurrence of resistance among Cladobotryum strains, which negatively affect the efficiency of treatments [82]. McKay et al. [95] reported the detection of a point mutation causing substitution from tyrosine to cysteine that removed an Acc I restriction site in the β-tubulin gene sequence of C. dendroides isolates resistant to MBC fungicides. Besides, C. mycophilum Type II isolate 192B1 was proved benzimidazole-resistant but sensitive to prochloraz-Mn, although prochloraz-Mn was unable to prevent spotting symptoms of cobweb disease [11]. The evidence reported suggests that it is necessary to count on alternative products to mitigate resistance occurrence, for example, the highly selective and effective metrafenone [15]. Nevertheless, fungicide discovery for mushroom crops is challenging and requires a priori knowledge about specificity for the relevant parasite while showing low toxicity for the host. Henceforth, it is difficult to expect the inclusion of novel fungicides to manage cobweb disease in mushroom crops in the short term.

3.3. Alternative Control and Breeding

Bioactive compounds extracted from different sources are interesting alternatives with proven antifungal activity tested as useful products to manage cobweb disease (Table 1). EOs from cinnamon, geranium, and spearmint completely inhibited the growth of C. dendroides, both by contact and the volatile phase were efficient, but low selectivity was reported, and the authors suggested the EOs can damage the host mycelium [76]. EOs from the Mediterranean aromatic plants Thymus vulgaris (main compounds p-cymene and thymol) and Satureja montana (main compounds carvacrol and p-cymene) were selective and efficient to inhibit mycelial growth of C. mycophilum in vitro, and reported significant control of cobweb disease, comparable to the fungicide treatment with metrafenone, when infected A. bisporus crops were treated with these EOs at 1%; although crop losses were noted in the first flush, suggesting some fungitoxic effect and crop delay [61]. The impact of cobweb disease in Agaricus and Pleurotus crops was also reduced significantly by the active component of the biofungicide Timorex 66 EC, tea tree oil; however, it showed significantly lower toxicity against C. dendroides mycelium than prochloraz-Mn in vitro [58,96].

Even though the mechanism underpinning cobweb disease of mushrooms is still unknown, genetic resources available for the researchers are gradually increasing, which can facilitate the development of studies on functional genomics fostering IDM strategies and facilitating programs for host breeding. For instance, the sequenced mitochondrial genomes of Hypomyces aurantius H.a0001 [97] and C. mycophilum MT108299 [98] have provided genetic resources for intra-species identification of the causal agent of cobweb disease, which represents significant information to design tailored control tools for a targeted species in local areas. The first complete genomes of the genus Cladobotryum were recently released (Table 2) [25,26]. The complete genome of C. protrusum strain CCMJ2080 (NCBI genome Acc. No RZGP00000000) showed that the long-interspersed element (LINE) detected in the genome (0.60%) could be related to the occurrence of resistance to DMI fungicides such as the commonly used prochloraz-Mn. The authors specifically suggest that fungicide resistance in Cladobotryum spp. maybe related to point mutations in one of the target genes (BcSdhB, cox10, cytb, CYP51, DHFR, DHPS, FKS1, FUR1, and tub2) [21]. In this respect, fungicides from benzophenone (like metrafenone), pyrimidinamines, and quinazoline groups pointing actin cytoskeleton-regulatory complex protein (PF12761), and NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (PF12853) are suggested as efficient to control C. protrusum. It is noteworthy that the genome encodes genes from CAZymes, secondary metabolites, or cytochrome P450s, contributing to mycotrophic lifestyle [25]. The later release of the complete genome of C. dendroides strain CCMJ2808 (NCBI genome Acc. No WWCI01000000) showed that, among different mushroom mycoparasites, Cladobotryum genus was closer to Mycogone than to Trichoderma according to phenotypic evidence [26]. Pathogenicity-related genes were predicted and analyzed, detecting gene families in C. dendroides strongly associated with pathogenicity (such as CAZymes and fungal effectors), virulence (genes related to secondary metabolites production), and resistance (C. dendroides shared few unique orthologous gene families with other mushroom mycoparasites such as C. protrusum and M. perniciosa) [26].

4. Wet Bubble (Mycogone Perniciosa)

4.1. Causative Agent and Symptoms of Disease

Wet bubble disease (WBD), caused by the mycoparasite M. perniciosa, is a worldwide disease affecting commercial cultivation of white button mushroom (A. bisporus) and other cultivated fungi such as Pleurotus citrinopileatus but also found in the wild, parasitizing a range of basidiomycetes [2,63,99,100,101,102]. For many years, outbreaks of WBD have been sporadic, but it is recently reported that the presence of this mycoparasite is expanding, particularly in China, where WBD can cause yield losses of about 15–30% [103,104,105,106]. A taxonomic and morphological description of M. perniciosa (Figure 1c) can be found in several studies [2,101,102].

M. perniciosa affects the morphogenesis of A. bisporus fruit bodies but not the vegetative mycelium [102]. The easily recognized symptoms of WBD include the presence of masses of deformed tissue with no signs of differentiation into stipe or cap, which can reach 10 cm in diameter (Figure 1c). The wet bubbles are initially white, fluffy, and spongy before they acquire a brown color and decay. Later, they can secrete amber liquid drops containing bacteria and spores and eventually rot, releasing an unpleasant smell [2]. A cross-section of deformed sporophores shows black circular areas just beneath the upper layer. The main source of inoculum is the casing material, while compost is not cited as a major source [2]. Like L. fungicola, M. perniciosa can be spread by water splashing and operators (contaminated tools, hands, clothes, etc.). Air can also transport conidia.

4.2. Chemical Control and Resistance

WBD is managed by cultural practices, sanitation, and chemical fungicides. By the mid-1970s, the control of WBD relied on the use of benzimidazole fungicides, mainly benomyl, because this fungicide was toxic against a wide range of fungi but was not effective in inhibiting the growth of most Basidiomycetes [41,42]. When these fungicides were firstly used in the mushroom industry, they provided excellent control of M. perniciosa. Besides, isolates from Spain and Serbia have been proved highly sensitive to iprodione and prochloraz-Mn [64,100]. Recently in China, with the aim of screening suitable fungicides for the control of WBD, 26 fungicides from different FRAC groups (https://www.frac.info/ (accessed on 23 February 2021)) were tested in vitro against M. perniciosa and the host A. bisporus, while 13 selected fungicides were tested in mushroom-growing rooms infected with M. perniciosa. Among the fungicides assessed, prochloraz-Mn (DMI-fungicide) and thiabendazole (MBC-fungicide) are still useful to manage WBD, fludioxonil (DMI-fungicide), diniconazole (DMI-fungicide), fenbuconazole (DMI-fungicide), and imazalil (DMI-fungicide) and were also reported as suitable alternatives to prevent the occurrence of resistant strains [106]. However, extensive research must be performed before further approval of fungicides to treat WBD, evaluating the presence of residues after treatment as well as clarifying toxicity over the environment and human beings. To date, no solid evidence of resistance occurrence has been reported among M. perniciosa strains which are certainly remarkable in comparison to the evidence reported for other mycoparasites. This could be related to the nature of the organism and a limited ability to generate mutations driven toward fungicide resistance.

4.3. Alternative Control and Breeding

Some EOs from aromatic plants can suppress the growth of M. perniciosa in vitro (Table 1). EO from savory (Satureja thymbra) expressed better antifungal activity against M. perniciosa than S. pomifera oil, and those of oregano and geranium expressed the strongest antifungal activity against the mycopathogen; since EOs are considered nontoxic and easily biodegradable, their application is also recommended for disinfection of commercial casing soil with 2% oregano oil before application on germinated compost [107]. Among a wide range of forty EOs under study, Lemon verbena (Lippia citriodora), lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus), and thyme (Thymus vulgaris) oils selectively inhibited the growth of M. perniciosa. Lemon verbena or thyme oils were efficient to prevent wet bubble when M. perniciosa was inoculated in the casing. Besides, in crop trial, the application of these oils, nerol and thymol (two major compounds of these substances), at a concentration of 40 μL L−1 showed a similar yield to those blocks treated with the fungicide prochloraz-Zn [65].

Highly WBD-resistant wild strains of button mushrooms from China have been reported, and the library of simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers generated during the study conforms a useful toolbox for the design of breeding programs to generate commercial WBD-resistant strains in addition to the precision mapping of QTL of WBD-resistant genes in A. bisporus [28]. Developing integrated programs for the successful management of WBD of button mushrooms requires knowledge from the genetic diversity and phenotypic virulence of M. perniciosa. In this sense, the amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis technique has been proved as efficient to distinguish the genetic variation among M. perniciosa isolates from China [105]. Ultimately, the targeting of genetic markers associated with disease incidence and parasite virulence will generate resources to breed A. bisporus. Genome resources recently generated in China through the release of the highly virulent strain of Hypomyces perniciosus HP10 (NCBI database under accession number: SPDT00000000) genome (Table 2) provided insights into the parasitic behavior of the organism, including the identification of significantly expanded protein families of transporters/carriers required for mycoparasitism and adaptation to rough environments (protein kinases, CAZymes, peptidases, cytochrome P450, and secondary metabolites) [24].

5. Green Mold (Trichoderma spp.)

5.1. Causative Agent and Symptoms of Disease

Green mold is a devastating disease for mushroom farmers in crops such as button mushroom, oyster mushroom, shiitake, winter mushroom, or milky mushroom (Calocybe indica) [108,109,110,111,112,113]. In December 2015, massive green mold epidemics caused by Trichoderma aggressivum f. aggressivum was reported to occur in Hungary, with nearly 100% crop loss in the infected button mushroom beds [114]. Symptoms of disease detected in compost and casing surface have been described as extensive sporulating green patches covering the substrates and generating brown spotting on mushroom caps [113] (Figure 1d). Several species belonging to the genus Trichoderma have been described as a causative agent for the disease including T. aggressivum [114], T. citrinoviride [109], T. pleuroticola, and T. pleuroti [112] or T. harzianum [111]. Different degree of virulence among biotypes is described, highlighting T. aggressivum f. europaeum and T. aggressivum f. aggressivum as the most dangerous parasites in button mushroom crops [113,115,116]. Other mushroom-substrate-inhabiting species such as T. atroviride are considered host competitors with reduced damage for the crop [2,116]. Morphologically the genus Trichoderma is characterized for producing heavy sporulation of small conidia, initially, white colonies turned to yellow and green and finally dark green depending on the species (Figure 1d). The different species from this genus are difficult to identify through taxonomy, so molecular identification is more often required [69,117].

The emergence of Trichoderma on the compost could be due to contamination during spawning. Trichoderma grows well on carbohydrates, and in this sense, seed grain is an important source of food and is very vulnerable. Once installed on the compost, the pathogen is able to colonize large areas since it is favored by the distribution of the seed grains in the compost mass [3].

Critical periods are the time of spawning and packaging of the compost when it is necessary to take extra precautions. The stage of colonization of the substrate is also critical, as there must be a good control of the temperature. The disease can be spread by general operations during cropping such as watering and by mean of pest flies acting as vectors for green mold [109,115].

5.2. Chemical Control and Resistance

Since green mold was considered historically a minor disease due to the relatively low impact when Phase II compost farming was conducted (which consist of the incubation of spawned compost in the growing facilities), the studies evaluating the efficiency of fungicides to prevent green mold is reduced.

The imidazole prochloraz-Mn has been proved effective against both T. pleuroticola and T. pleuroti, causal agents of green mold in P. ostreatus, both in in vitro and in crop trials when artificially infected [112]. T. pleuroti was more sensitive to the fungicide than T. pleuroticola, which points to the identification of the target species as an important intermediate step to optimize effective fungicide treatments in mushroom crops. Besides, the T. aggressivum f. europaeum strains T76, T77, and T85, isolated from green mold infecting compost in Serbia, when confronted to a range of fungicides, showed the largest sensitivity to chlorothalonil and carbendazim and were less susceptible to iprodione, some resistant to thiophanate-methyl, and resistant to trifloxystrobin [118].

5.3. Alternative Control and Breeding

Biochemical substances such as EOs from plants (Table 1) have shown strong activity against Trichoderma aggressivum f. europaeum, particularly basil and mint oils [119]. However, as noted before, some of these substances exhibit low selectivity and may damage the crop.

In addition, commercial biofungicides such as Serenade® WP (Bayern, Germany), based on Bacillus velezensis QST713, and Ekstrasol F SC (BioGenesis d.o.o., Belgrade, Serbia), based on Bacillus subtilis Ch-13 1, have been noted effective to control green mold disease when T. aggressivum f. europaeum T77 was artificially inoculated in mushroom plots, showing a biological treatment comparable or even better than those plots treated with prochloraz-Mn [120]. Although mechanisms involving biocontrol of green mold from biofungicides have been barely described, according to Pandin et al. [121,122], the mechanisms acting in the antagonism of T. aggressivum by B. velezensis QST713 may be a combination of (i) competence in the environmental niche through the formation of competitive biofilm to exclude T. aggressivum, (ii) production and secretion of compounds with antifungal activity against the parasite, and (iii) release of signaling molecules, such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) or the quorum-sensing-controlled processes, which can lead to defense response in A. bisporus or reduce parasite activity. The environmental niche where mushrooms develop and fructify is a highly dynamic and rich microbiome where multiple agents act and its configuration may have a direct impact on yield performance and disease occurrence [32,123,124]. Bacteria genera inhabiting casing material, including Bacillus and Pseudomonas, can be responsible for the casing fungistasis of mycoparasites observed in the absence of the host mycelium [125], however, the host mycelium modifies the microbiome structure breaking the fungistatic equilibrium and the native microbiota results inefficient to suppress mycoparasites under conditions of high disease pressure [32,48]. Bearing in mind the described behavior, selected microbiota isolated from mushroom substrates can be effectively reintroduced during cultivation as biological control agents (BCAs) to control green mold. For instance, the casing gram-negative bacteria Pseudomonas putida has been noted to promote the growth of harmful mycelium of T. aggressivum, and conversely casing inhabitants have been proved to reduce the growth of the parasitic mycelium but enhancing sporulation (Pseudomonas tolaasii) [113]. Among fifty bacterial strains isolated from mushroom compost, Bacillus subtillis B-38 inhibited T. harzianum T54 (48.08%) and T. aggressivum f. europaeum T77 (52.25%) mycelium growth in vitro. In plot trials, those plots artificially inoculated with the cited Trichoderma strains and treated with Bacillus subtillis B-38 presented significantly lower disease incidence comparing to the control and results for disease control and yield harvested were comparable to the plots treated with prochloraz-Mn [126]. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens B-129 (NCBI GenBank Ac No KT692726) isolated from Phase II compost and B. amyloliquefaciens B-268 (NCBI GenBank Ac No KT692735) isolated from casing soil have proved antagonistic activity against T. aggressivum f. europaeum T77, T. harzianum T54, T. koningii T39, and T. atroviride T33 in vitro, which indicates broad-spectrum activity among these gram-positive bacteria towards members of the Trichoderma genus [127].

Understanding genetic cues driving green mold disease can be crucial for the development of breeding strategies to product-resistant host strains. In this context, QTL in A. bisporus associated with Trichoderma lytic enzymes and metabolites have been described [27]. The authors suggest that the ability of Agaricus to resist or adapt to Trichoderma lytic enzymes and antifungal metabolites could be related to the fitness of the host strain, lower incidence and disease severity is associated with the prompt colonization of the compost by A. bisporus before T. aggressivum develops. Due to the evidence reported, it is highly advisable to prevent early contamination at the beginning of the crop cycle during the compost production and mycelium germination when strict hygiene measures must apply to prevent contamination. Resistance associated with laccase activity as a defense response of A. bisporus to T. aggressivum toxins has been also described, particularly associated with A. bisporus lcc2 gene (laccase 2) [20]. Laccase production in A. bisporus increased in vitro in strains U1 and SB65 to confront toxic metabolites produced by T. aggressivum. The commercial brown strains SB65 showed enhanced defensive mechanisms, which can contribute to generating resistant strains against green mold through breeding programs. Besides, cell-wall-degrading enzymes encoded by three T. aggressivum genes: prb1 (encoding a proteinase), ech42 (encoding an endochitinase), and a β-glucanase gene, have been described and differences of β-glucanase transcription between the sensitive A. bisporus strain U1 (off-white hybrid) and the resistant A. bisporus strain SB65 (large brown strain) were noted [128]. In this framework, a strategy to design resistant strains for green mold disease may be the identification of genes that contribute to disease development because preventing the expression of targeted genes could facilitate the inhibition of the disease.

6. Recommended Hygienic Measures for the Control of Fungal Diseases

6.1. Hygienic Measures Common to the Four Diseases Described

To cope with fungal diseases, a number of management strategies can be designed to prevent disease outbreaks and avoid disease dispersion. The following are the most common general hygienic measures [2,3,129]: (1) Any agronomical activity which requires entering the growing facility should always be carried out from newer crops to the elder ones; (2) Disease vectors should be avoided by controlling fly and mite populations; (3) Batches of raw casing materials should not remain near crop facilities, otherwise, sealed spaces must be designed for casing storage to prevent spore contamination.; (4) Remove all affected mushrooms before applying agronomical actions such as harvesting or watering; (5) Disinfection of clothes, footwear and tools in critical areas is key action; (6) Boxes employed for mushroom collection must be disinfected before entering the growing facility and never come from nearby contaminated crops in the farm; (7) Do not lengthen unnecessarily the crop cycle (2–3 flushes maximum); (8) Once the crop cycle is terminated, when available, a cooking-out step on the crops must be applied using steam water to kill pathogens followed by thoroughly cleaning and disinfection of empty facilities.

6.2. Hygienic Measures Especially Recommended for the Control of Cobweb Disease

Particularly in the case of cobweb disease [88,89,130]: (1) Do not water or manipulate cropping areas that are affected by cobweb. It is recommended to place damp paper over the affected area (infected casing material or basidiomes) in such a way that the edges exceeded the pathogenic colony by several centimeters to prevent conidia release from sporulating patches; (2) Avoid long periods of high humidity on the carpophores and ensure a good rate of evaporation through the compost to prevent conidia germination on damp mushroom caps; (3) Prevent air ventilation and dispose slightly of suboptimal temperature and relative humidity to prevent disease dispersion and conidia germination when several patches of the disease have been noted.

6.3. Hygienic Measures Especially Recommended for the Control of Green Mould Disease

Especially in the case of green mold disorder, the most important measurements are [2,129,130]: (1) Ensure good mixing of base materials during Phase I of composting and avoid the appearance of anaerobiosis zones; (2) Ensure that the whole mass of compost receives good pasteurization. There should be a good flow of air through the whole mass to prevent the development of Trichoderma due to anaerobiosis; (3) Dispose of adequate air filters in Phase II rooms, areas of spawning, and incubation rooms; (4) Prevent excessive moisture in the final compost (<70%); (5) Control the levels of ammonia during phase II; (6) The packaging area must be sealed and equipped with positive pressure filtered air. Intensive cleaning of these areas must be performed at least once a week; (7) The spawning equipment must be disinfected at the end of the day; (8) Avoid unnecessary operations and temperatures of over 27–28 °C during the incubation phase.; (9) To prevent cap spotting, avoid humid conditions on the caps and poor evaporation rate through the carpophores when they develop.

7. Conclusions

The present work offers a comprehensive review in respect to the most harmful mycoparasites of cultivated mushrooms by describing the causal agents and disease symptoms of the worldwide occurring DBD, cobweb disease, WBD, and green mold and describing attempts for chemical control and evidence of disease resistance to finally introduce alternative methods for disease control and genomic resources to design programs for host breeding. This review is based on the authors’ long-lasting experience on the topic to compile topic knowledge as a toolbox for the design of strategies for integrated disease management of fungal diseases in mushroom crops, prevent the outbreak of resistant isolates, and eventually fight resistant variants through alternative control measurements.

In summary, evidence of reduced sensitivity and resistance occurrence has been reported among fungal parasitic strains continuously exposed to most of the active substances historically employed by the mushroom industry. Noteworthy, continuous exposure to the same active substances is related to a consistent trend, indicating higher tolerance among the most recent isolates. The great variability observed among fungicides with a different mode of action highlights the necessity for research studies to select suitable active substances that can be complementary. Complementary treatments may avoid overusing a single product to preclude the occurrence of resistant strains. Hence, growers and the mushroom industry have several challenges to overcome risks derived from the resistant evidence described, including the nature of the crop (increasing the pesticide doses is not a suitable alternative to fight mycoparasites), the restrictive legislative environment, and consumer demand for healthier and environmentally respectful cropping systems.

Natural plant-derived fungicides can provide a wide variety of compounds as an alternative to synthetic fungicides once tested selective for parasites and safe both for human health and the environment. Compost teas obtained from different agronomical wastes can be also efficient alternatives for the control of fungal diseases due to the intensive activity of the microbial community inhabiting these broths. Besides, comparing to the commercial biocontrol agents in the market, strains isolated from mushroom substrates may represent a sustainable solution tailor-made to this particular crop since the biocontrol agents will be perfectly adapted to the environmental niche associated with the mushrooms. Anyhow, the cost-effectiveness of treatments alternative to chemical fungicides must be taken into account and, in our opinion, both types of preventive treatments must cohabit in the short- and medium-term.

Genomic resources regarding mushroom mycoparasites have been generated within the last ten years. Further efforts must be taken into account to generate larger datasets through sequencing with the aim of enlightening the mechanism involved in host–parasite interactions, and ultimately design programs for the breeding of resistant varieties.

Intensive cleaning of compost yards and growing facilities, the integration of bioactive compounds, and the generation of further genomic data with a deepening understanding of available resources through data mining will be key inputs for designing IDM programs while integrating approved fungicides and good agricultural practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J.G. and J.C.; investigation, F.J.G. and J.C.; resources, F.J.G., M.J.N. and J.C.; data curation, F.J.G. and J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.; writing—review and editing, F.J.G., M.J.N. and J.C.; visualization, F.J.G., M.J.N. and J.C.; supervision, F.J.G. and J.C.; funding acquisition, F.D. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by MINECO (Spain) and FEDER (Projects RTA2010-00011-C02 and E-RTA2014- 00004-C02) with the support of Consejería de Agricultura de Castilla-La Mancha and Patronato de Desarrollo Provincial de la Diputación de Cuenca.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Some images have been handed over by Antonio Martinez (CIES).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Royse, D.J.; Baars, J.; Tan, Q. Current Overview of Mushroom Production in the World. In Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms: Technology and Applications; Zied, D.C., Pardo-Gimenez, A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2017; pp. 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, J.T.; Gaze, R.H. Mushroom Pest and Disease Control: A Colour Handbook, 1st ed.; Manson Publishing Ltd. Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008; 192p. [Google Scholar]

- Gea, F.J.; Navarro, M.J. Mushroom Diseases and Control. In Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms: Technology and Applications; Zied, D.C., Pardo-Gimenez, A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2017; pp. 239–259. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, G.M.; Carrasco, J.; Gea, F.J.; Navarro, M.J. Biological Control of Microbial Pathogens in Edible Mushrooms. In Biology of Macrofungi; Singh, B.P., Passari, A.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Largeteau, M.L.; Savoie, J.M. Microbially induced diseases of Agaricus bisporus: Biochemical mechanisms and impact on commercial mushroom production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 86, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoder, J.B.; Sinden, J.W.; Hauser, E. Experience with zinc ethylene bis-dithio-carbamate as a fungicide in mushroom cultivation. Mushr. Sci. 1950, 1, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wuest, P.; Cole, H.; Sanders, P.L. Tolerance of Verticillium malthousei to benomyl. Phytopathology 1974, 64, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, G.J.; van Zaayen, A. Resistance to benzimidazole fungicides in pathogenic strains of Verticillium fungicola. Neth. J. Plant Pathol. 1975, 81, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.T.; Yarham, D.J. The incidence of benomyl tolerance in Verticillium fungicola, Mycogone perniciosa and Hypomyces rosellus in mushroom crops. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1976, 84, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, H.M.; Gaze, R.H. Fungicide resistance among Cladobotryum spp.—causal agents of cobweb disease of the edible mushroom Agaricus bisporus. Mycol. Res. 2000, 104, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, H.M. Fungicide control of mushroom cobweb disease caused by Cladobotryum strains with different benzimidazole resistance profiles. Pest Manag. Sci. 2006, 2, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grogan, H.M.; Keeling, C.; Jukes, A.A. In vivo response of the mushroom pathogen Verticillium fungicola (dry bubble) to prochloraz-manganese. In Proceedings of the BCPC Conference: Pests and Diseases, Brighton, UK, 13–16 November 2000; British Crop Protection Council: Brighton, UK, 2000; pp. 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Gea, F.J.; Navarro, M.J.; Tello, J.C. Reduced sensitivity of the mushroom pathogen Verticillium fungicola to prochloraz-manganese in vitro. Mycol. Res. 2005, 109, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyck, N.; Sedeyn, P.; Demeulemeester, M.; Grogan, H. Evaluation of metrafenone against Verticillium and Cladobotryum spp.—Causal agents of dry bubble and cobweb disease. In Science and Cultivation of Edible and Medicinal Fungi–Mushroom Science XIX. Proceedings of the 19th International Congress on the Science and Cultivation of Edible and Medicinal Fungi; Baars, J.J.P., Sonnenberg, A.S.M., Eds.; Wageningen University and Research Centre: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, J.; Navarro, M.J.; Santos, M.; Gea, F.J. Effect of five fungicides with different modes of action on cobweb disease (Cladobotryum mycophilum) and mushroom yield. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2017, 171, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luković, J.; Milijašević-Marčić, S.; Hatvani, L.; Kredics, L.; Szűcs, A.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Duduk, N.; Vico, I.; Potočnik, I. Sensitivity of Trichoderma strains from edible mushrooms to the fungicides prochloraz and metrafenone. J. Environ. Sci. Health B 2020, 56, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zaayen, A.; Van Adrichem, J.C.J. Prochloraz for control of fungal pathogens of cultivated mushrooms. Neth. J. Plant Pathol. 1982, 88, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulou, P.; Philippoussis, A.; Kastanias, M.; Flouri, F.; Chrysayi-Tokousbalides, M. Effect of famoxadone, tebuconazole and trifloxystrobin on Agaricus bisporus productivity and quality. Sci. Hortic. 2006, 109, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysayi-Tokousbalides, M.; Kastanias, M.A.; Philippoussis, A.; Diamantopoulou, P. Selective fungitoxicity of famoxadone, tebuconazole and trifloxystrobin between Verticillium fungicola and Agaricus bisporus. Crop Prot. 2007, 26, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjaarda, C.P.; Abubaker, K.S.; Castle, A.J. Induction of lcc2 expression and activity by Agaricus bisporus provides defence against Trichoderma aggressivum toxic extracts. Microb. Biotechnol. 2015, 8, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenberg, A.S.; Baars, J.J.P.; Gao, W.; Visser, R.G. Developments in breeding of Agaricus bisporus var. bisporus: Progress made and technical and legal hurdles to take. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 1819–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, E.; Kohler, A.; Baker, A.R.; Foulongne-Oriol, M.; Lombard, V.; Nagye, L.G.; Martin, F. Genome sequence of the button mushroom Agaricus bisporus reveals mechanisms governing adaptation to a humic-rich ecological niche. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 17501–17506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, A.M.; Aminuddin, F.; Williams, K.; Batstone, T.; Barker, G.L.; Foster, G.D.; Bailey, A.M. Genome sequence of Lecanicillium fungicola 150-1, the causal agent of dry bubble disease. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2019, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Sossah, F.L.; Sun, L.; Fu, Y.; Li, Y. Genome analysis of Hypomyces perniciosus, the causal agent of wet bubble disease of button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). Genes 2019, 10, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sossah, F.L.; Liu, Z.; Yang, C.; Okorley, B.A.; Sun, L.; Fu, Y.; Li, Y. Genome sequencing of Cladobotryum protrusum provides insights into the evolution and pathogenic mechanisms of the cobweb disease pathogen on cultivated mushroom. Genes 2019, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Liu, X.; Peng, B.; Liu, P.; Li, Z.; Dai, Y.; Xiao, S. Genomic features of Cladobotryum dendroides, which causes cobweb disease in edible mushrooms, and identification of genes related to pathogenicity and mycoparasitism. Pathogens 2020, 9, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foulongne-Oriol, M.; Minvielle, N.; Savoie, J.M. QTL for resistance to Trichoderma lytic enzymes and metabolites in Agaricus bisporus. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Mushroom Biology and Mushroom Products, Arcachon, France, 4–7 October 2011; Savoie, J.M., Foulougne-Oriol, M., Largeteau, M., Barroso, G., Eds.; INRA: Bordeaux, France, 2011; pp. 190–195. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Song, B.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Q.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Identification of resistance to wet bubble disease and genetic diversity in wild and cultivated strains of Agaricus bisporus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berendsen, R.L.; Baars, J.J.; Kalkhove, S.I.; Lugones, L.G.; Wösten, H.A.; Bakker, P.A. Lecanicillium fungicola: Causal agent of dry bubble disease in white-button mushroom. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2010, 11, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zare, R.; Gams, W. A revision of the Verticillium fungicola species complex and its affinity with the genus Lecanicillium. Mycol. Res. 2008, 112, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrparvar, M.; Mohammadi Goltapeh, E.; Safaei, N. Resistance of Iranian Lecanicillium fungicola to benzimidazole and ergosterol demethylation inhibiting fungicides. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2013, 15, 389–396. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, J.; Tello, M.L.; de Toro, M.; Tkacz, A.; Poole, P.; Pérez-Clavijo, M.; Preston, G. Casing microbiome dynamics during button mushroom cultivation: Implications for dry and wet bubble diseases. Microbiology 2019, 165, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caitano, C.E.; Iossi, M.R.; Pardo-Giménez, A.; Júnior, W.G.V.; Dias, E.S.; Zied, D.C. Design of a useful diagrammatic scale for the quantification of Lecanicillium fungicola disease in Agaricus bisporus cultivation. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 4037–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thao, L.D.; Binh, V.T.P.; Khanh, T.N.; Thanh, H.M.; Hien, L.T.; Anh, P.T.; Trang, T.T.T.; Dung, N.V.; Hoai, H.T. First report of Lecanicillium fungicola var. aleophilum infecting white-button mushroom in Vietnam. New Dis. Rep. 2020, 41, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlowe, A.; Romaine, C.P. Dry bubble of oyster mushroom caused by Verticillium fungicola. Plant Dis. 1982, 66, 859–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea, F.J.; Tello, J.C.; Navarro, M.J. Occurrence of Verticillium fungicola var. fungicola on Agaricus bitorquis mushroom crops in Spain. J. Phytopathol. 2003, 151, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture. Defending the Mushroom Industry against Disease. Available online: https://www.utas.edu.au/tia/news-events/news-items/defending-the-mushroom-industry-against-disease (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Gomez, A. New technology in Agaricus bisporus cultivation. In Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms: Technology and Applications; Zied, D.C., Pardo-Gimenez, A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2017; pp. 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Piasecka, J.; Kavanagh, K.; Grogan, H. Detection of sources of Lecanicillium (Verticillium) fungicola on mushroom farms. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Mushroom Biology and Mushroom Products, Arcachon, France, 4–7 October 2011; Savoie, J.M., Foulougne-Oriol, M., Largeteau, M., Barroso, G., Eds.; INRA: Bordeaux, France, 2011; pp. 479–484. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, W.C.; Preece, T.F. Sources of Verticillium fungicola on a commercial mushroom farm in England. Plant Pathol. 1987, 36, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, G.J.; Fuchs, A. On the specificity of the in vitro and in vivo antifungal activity of benomyl. Neth. J. Plant Pathol. 1970, 76, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgington, L.V.; Khew, K.I.; Barron, G.L. Fungitoxic spectrums of benzimidazole compounds. Phytopathology 1971, 61, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snel, M.; Fletcher, J.T. Benomyl and thiabendazole for the control of mushroom diseases. Plant Dis. Rep. 1971, 55, 120–121. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnen, A.M.; Hopkins, C. Fungicide resistance and population variation in Verticillium fungicola, a pathogen of the button mushroom, Agaricus bisporus. Mycol. Res. 1997, 101, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potočnik, I.; Vukojević, J.; Stajić, M.; Tanović, B.; Todorović, B. Fungicide sensitivity of selected Verticillium fungicola isolates from Agaricus bisporus farms. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2008, 60, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea, F.J.; Tello, J.C.; Honrubia, M. In vitro sensitivity of Verticillium fungicola to selected fungicides. Mycopathologia 1996, 136, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, J.T.; Hims, M.J.; Hall, R.J. The control of bubble diseases and cobweb disease of mushrooms with prochloraz. Plant Pathol. 1983, 32, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, J.; Preston, G.M. Growing edible mushrooms: A conversation between bacteria and fungi. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 858–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianez, F.; Santos, M.; Boix, A.; de Cara, M.; Trillas, I.; Avilés, M.; Tello, J.C. Grape marc compost tea suppressiveness to plant pathogenic fungi: Role of siderophores. Compost Sci. Util. 2006, 14, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soković, M.; van Griensven, L.J.L.D. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils and their components against the three major pathogens of the cultivated button mushroom, Agaricus bisporus. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2006, 116, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanović, B.; Potočnik, I.; Delibašic, G.; Ristić, M.; Kostić, M.; Marković, M. In vitro effect of essential oils from aromatic and medicinal plants on mushroom pathogens: Verticillium fungicola var. fungicola, Mycogone perniciosa, and Cladobotryum sp. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2009, 61, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea, F.J.; Navarro, M.J.; Tello, J.C. Potential application of compost teas of agricultural wastes in the control of the mushroom pathogen Verticillium fungicola. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2009, 116, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, F.; Santos, M.; Diánez, F.; Carretero, F.; Gea, F.J.; Yau, J.A.; Navarro, M.J. Characters of compost teas from different sources and their suppressive effect on fungal phytopathogens. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 29, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gea, F.J.; Carrasco, J.; Diánez, F.; Santos, M.; Navarro, M.J. Control of dry bubble disease (Lecanicillium fungicola) in button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) by spent mushroom substrate tea. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 138, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrparvar, M.; Goltapeh, E.M.; Safaie, N.; Ashkani, S.; Hedesh, R.M. Antifungal activity of essential oils against mycelia growth of Lecanicillium fungicola var. fungicola and Agaricus bisporus. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016, 84, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, T.L.; Belan, L.L.; Zied, D.C.; Dias, E.S.; Alves, E. Essential oils in the control of dry bubble disease in white button mushroom. Cienc. Rural 2017, 47, e20160780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luković, J.; Stepanović, M.; Todorović, B.; Milijašević-Marčić, S.; Duduk, N.; Vico, I.; Potočnik, I. Antifungal activity of cinnamon and clove essential oils against button mushroom pathogens Cladobotryum dendroides (Bull.) W. Gams & Hooz. and Lecanicillium fungicola var. fungicola (Preuss) Hasebrauk. Pestic. Phytomed. 2018, 33, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Potočnik, I.; Vukojević, J.; Stajić, M.; Rekanović, E.; Stepanović, M.; Milijašević, S.; Todorović, B. Toxicity of biofungicide Timorex 66 EC to Cladobotryum dendroides and Agaricus bisporus. Crop Prot. 2010, 29, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianez, F.; Santos, M.; Parra, C.; Navarro, M.J.; Blanco, R.; Gea, F.J. Screening of antifungal activity of twelve essential oils against eight pathogenic fungi of vegetables and mushroom. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, I.; Sossah, F.L.; Yang, Y.; Li, D.; Li, S.; Fu, Y.; Li, Y. Identification of resistance to cobweb disease caused by Cladobotryum mycophilum in wild and cultivated strains of Agaricus bisporus and screening for bioactive botanicals. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 14758–14765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea, F.J.; Navarro, M.J.; Santos, M.; Diánez, F.; Herraiz-Peñalver, D. Screening and evaluation of essential oils from mediterranean aromatic plants against the mushroom cobweb disease, Cladobotryum mycophilum. Agronomy 2019, 9, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glamočlija, J.; Soković, M.; Vukojević, J.; Milenković, I.; Van Griensven, L.J.L.D. Chemical composition and antifungal activities of essential oils of Satureja thymbra L. and Salvia pomifera ssp. calycina (Sm.) Hayek. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2006, 18, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glamočlija, J.; Soković, M.; Grubisic, D.; Vukojevic, J.; Milinekovic, I.; Ristic, M. Antifungal activity of Critmum maritimum essential oil and its components against mushroom pathogen Mycogone perniciosa. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2009, 45, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potočnik, I.; Vukojević, J.; Stajic, M.; Tanovic, B.; Rekanovic, E. Sensitivity of Mycogone perniciosa, pathogen of culinary-medicinal button mushroom Agaricus bisporus (J. Lge) Imbach (Agaricomycetideae), to selected fungicides and essential oils. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2010, 12, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnier, T.; Combrinck, S. In vitro and in vivo screening of essential oils for the control of wet bubble disease of Agaricus bisporus. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2010, 76, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabharwal, A.; Kapoor, S. In vitro effect of essential oils on mushroom pathogen Mycogone perniciosa causal agent of wet bubble disease of white button mushroom. Indian J. Appl. Res. 2014, 4, 482–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokouhi, D.; Seifi, A. Organic extracts of seeds of Iranian Moringa peregrina as promising selective biofungicide to control Mycogone perniciosa. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 101848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glamočlija, J.; Soković, M.; Tešević, V.; Linde, G.A.; Barros Colauto, N. Chemical characterization of Lippia alba essential oil: An alternative to control green molds. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2011, 42, 1537–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosanović, D.; Potočnik, I.; Duduk, B.; Vukojević, J.; Stajić, M.; Rekanović, E.; Milijašević-Marčić, S. Trichoderma species on Agaricus bisporus farms in Serbia and their biocontrol. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2013, 163, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, R.; Wang, J.; Cheng, M.; Lu, W.; Chen, M.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X. Development and characterization of corn starch/PVA active films incorporated with carvacrol nanoemulsions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 1631–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanhaeian, A.; Nazifi, N.; Ahmadi, F.S.; Akhlaghi, M. Comparative study of antimicrobial activity between some medicine plants and recombinant Lactoferrin peptide against some pathogens of cultivated button mushroom. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 2525–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- On, A.; Wong, F.; Ko, Q.; Tweddell, R.J.; Antoun, H.; Avis, T.J. Antifungal effects of compost tea microorganisms on tomato pathogens. Biol. Control 2015, 80, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianez, F.; Marín, F.; Santos, M.; Gea, F.J.; Navarro, M.J.; Piñeiro, M.; González, J.M. Genetic analysis and in vitro enzymatic determination of bacterial community in compost teas from different sources. Compost. Sci. Util. 2018, 26, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, H.; Hashemi, M.; Sharifi, K. The effect of spent mushroom compost on Lecanicillium fungicola in vivo and in vitro. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2012, 45, 2120–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea, F.J.; Santos, M.; Diánez, F.; Tello, J.C.; Navarro, M.J. Effect of spent mushroom compost tea on mycelial growth and yield of button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 2765–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geösel, A.; Szabó, A.; Akan, O.; Szarvas, J. Effect of essential oils on mycopathogens of Agaricus bisporus. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Mushroom Biology and Mushroom Products (ICMBMP8), New Delhi, India, 19–22 November 2014; Solan, H.P., Ed.; ICAR-Directorate of Mushroom Research: Solan, India, 2014; pp. 530–535. [Google Scholar]

- Zied, D.C.; Nunes, J.S.; Nicolini, V.F.; Gimenez, A.P.; Rinker, D.L.; Dias, E.S. Tolerance to Lecanicillium fungicola and yield of Agaricus bisporus strains used in Brazil. Sci. Hort. 2015, 190, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.M.; Collopy, P.D.; Thomas, D.J.; Sergeant, M.R.; Costa, A.M.; Barker, G.L.; Mills, P.R.; Challen, M.P.; Foster, G.D. Transcriptomic analysis of the interactions between Agaricus bisporus and Lecanicillium fungicola. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2013, 55, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Lee, Y.H.; Cho, K.M.; Lee, J.Y. First report of cobweb disease caused by Cladobotryum mycophilum on the edible mushroom Pleurotus eryngii in Korea. Plant Dis. 2012, 96, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, C.G.; Lee, C.Y.; Seo, G.S.; Jung, H.Y. Characterization of species of Cladobotryum which cause cobweb disease in edible mushrooms grown in Korea. Mycobiology 2012, 40, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkireddy, K.; Khonsuntia, W.; Kües, U. Mycoparasite Hypomyces odoratus infests Agaricus xanthodermus fruiting bodies in nature. AMB Express 2020, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakwiya, A.; Van der Linde, E.J.; Korsten, L. In vitro sensitivity testing of Cladobotryum mycophilum to carbendazim and prochloraz manganese. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2015, 111, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chakwiya, A.; Van der Linde, E.J.; Chidamba, L.; Korsten, L. Diversity of Cladobotryum mycophilum isolates associated with cobweb disease of Agaricus bisporus in the south African mushroom industry. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 154, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, B.; Lu, B.H.; Liu, X.L.; Wang, Y.; Ma, G.L.; Gao, J. First report of Cladobotryum mycophilum causing cobweb on Ganoderma lucidum cultivated in Jilin province, China. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea, F.J.; Carrasco, J.; Suz, L.M.; Navarro, M.J. Characterization and pathogenicity of Cladobotryum mycophilum in Spanish Pleurotus eryngii mushroom crops and its sensitivity to fungicides. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2017, 147, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea, F.J.; Navarro, M.J.; Suz, L.M. First report of cobweb disease caused by Cladobotryum dendroides on shiitake mushroom (Lentinula edodes) in Spain. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea, F.J.; Navarro, M.J.; Suz, L.M. Cobweb disease on oyster culinary-medicinal mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) caused by the mycoparasite Cladobotryum mycophilum. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 101, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, J.; Navarro, M.J.; Gea, F.J. Cobweb, a serious pathology in mushroom crops: A review. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adie, B.; Grogan, H.; Archer, S.; Mills, P. Temporal and spatial dispersal of Cladobotryum conidia in the controlled environment of a mushroom growing room. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 7212–7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, C.R.; Cooke, R.C.; Burden, L.J. Ecophysiology of Dactylium dendroides—The causal agent of cobweb mould. In Science and Cultivation of Edible Fungi, Vol. 1. 14th International Congress on the Science and Cultivation of Edible Fungi; Elliott, T.J., Ed.; Balkema: London, UK, 1991; pp. 365–372. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, J.; Navarro, M.J.; Santos, M.; Diánez, F.; Gea, F.J. Incidence, identification and pathogenicity of Cladobotryum mycophilum, causal agent of cobweb disease on Agaricus bisporus mushroom crops in Spain. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2016, 268, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamm, H.; Põldmaa, K. Diversity, host associations and phylogeography of temperate aurofusarin producing Hypomyces/Cladobotryum including causal agents of cobweb disease of cultivated mushrooms. Fungal Biol. 2013, 117, 348–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, J. Parasitic fungi—A recurring nightmare. Mushroom Bus. 2018, 10, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU). Concerning the Non-Renewal of the Approval of the Active Substance Chlorothalonil in Accordance with Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council Concerning the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market, and Amending Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No. 540/2011. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, L114, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, G.J.; Egan, D.; Morris, E.; Brown, A.E. Identification of benzimidazole resistance in Cladobotryum dendroides using a PCR-based method. Mycol. Res. 1998, 102, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potočnik, I.; Stepanović, M.; Rekanović, E.; Todorović, B.; Milijašević-Marčić, S. Disease control by chemical and biological fungicides in cultivated mushrooms: Button mushroom, oyster mushroom and shiitake. Pestic. Phytomed. 2015, 30, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ming, R.; Lin, L.; Lin, X.; Lin, Y.; Li, X.; Xie, B.; Wen, Z. Analysis of the mitochondrial genome in Hypomyces aurantius reveals a novel twintron complex in fungi. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Fu, R.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Lu, D. The complete mitochondrial genome of Cladobotryum mycophilum (Hypocreales: Sordariomycetes). Mitochondrial DNA B 2020, 5, 2595–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieterse, Z. Mycogone perniciosa, a Pathogen of Agaricus bisporus. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, November 2005; 104p. [Google Scholar]

- Gea, F.J.; Tello, J.C.; Navarro, M.J. Efficacy and effects on yield of different fungicides for control of wet bubble disease of mushroom caused by the mycoparasite Mycogone perniciosa. Crop Prot. 2010, 29, 1021–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouser, S.; Shah, S. Isolation and identification of Mycogone perniciosa, causing wet bubble disease in Agaricus bisporus cultivation in Kashmir. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 8, 4804–4809. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.L.; Xu, J.Z.; Kakishima, M.; Li, Y. First report of wet bubble disease caused by Hypomyces perniciosus on Pleurotus citrinopileatus in China. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, X.; Chen, B.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Wen, Z. Analysis of genetic diversity and development of SCAR Markers in a Mycogone perniciosa population. Curr. Microbiol. 2016, 73, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Li, D.; Chen, L.; Li, Y. Genetic diversity analysis of Mycogone perniciosa causing wet bubble disease of Agaricus bisporus in china using SRAP. J. Phytopathol. 2016, 164, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Sossah, F.L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Dai, Y.; Song, B.; Li, Y. Genetic and pathogenic variability of Mycogone perniciosa isolates causing wet bubble disease on Agaricus bisporus in China. Pathogens 2019, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, N.; Ruan, H.; Jie, Y.; Chen, F.; Du, Y. Sensitivity and efficacy of fungicides against wet bubble disease of Agaricus bisporus caused by Mycogone perniciosa. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 157, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soković, M.D.; Glamočlija, J.M.; Ćirić, A.D. Natural products from plants and fungi as fungicides. In Fungicides: Showcases of Integrated Plant Disease Management from Around the World; Nita, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013; pp. 185–232. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.G.; Weon, H.Y.; Seok, S.J.; Lee, K.H. In vitro antagonistic characteristics of bacilli isolates against Trichoderma spp. and three species of mushrooms. Mycobiology 2008, 36, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kwon, H.W.; Tang, L.; Kim, S.H. Identification and characterization of Trichoderma citrinoviride isolated from mushroom fly-infested oak log beds used for shiitake cultivation. Plant Pathol. J. 2012, 28, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kwon, H.W.; Yun, Y.H.; Kim, S.H. Identification and characterization of Trichoderma species damaging shiitake mushroom bed-logs infested by Camptomyia pest. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 26, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.; Kumar, M.; Singh, J.K.; Goyal, S.P.; Singh, S. Management of the green mould of milky mushroom (Calocybe indica) by fungicides and botanicals. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 4931–4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, G.; Montanari, M.; Righini, H.; Roberti, R. Trichoderma species associated with green mould disease of Pleurotus ostreatus and their sensitivity to prochloraz. Plant Pathol. 2019, 68, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosanovic, D.; Grogan, H.; Kavanagh, K. Exposure of Agaricus bisporus to Trichoderma aggressivum f. europaeum leads to growth inhibition and induction of an oxidative stress response. Fungal Biol. 2020, 124, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatvani, L.; Kredics, L.; Allaga, H.; Manczinger, L.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Kuti, K.; Geösel, A. First report of Trichoderma aggressivum f. aggressivum green mold on Agaricus bisporus in Europe. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazin, M.; Harvey, R.; Andreadis, S.; Pecchia, J.; Cloonan, K.; Rajotte, E.G. Mushroom sciarid fly, Lycoriella ingenua (Diptera: Sciaridae) adults and larvae vector Mushroom Green Mold (Trichoderma aggressivum ft. aggressivum) spores. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2019, 54, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğdu, M.; Kurbetli, İ.; Kitapçı, A.; Sülü, G. Aggressiveness of green mould on cultivated mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) in Turkey. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2020, 127, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, G.J.; Dodd, S.L.; Gams, W.; Castlebury, L.A.; Petrini, O. Trichoderma species associated with the green mold epidemic of commercially grown Agaricus bisporus. Mycologia 2002, 94, 146–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosanovic, D.; Potocnik, I.; Vukojevic, J.; Stajic, M.; Rekanovic, E.; Stepanovic, M.; Todorovic, B. Fungicide sensitivity of Trichoderma spp. from Agaricus bisporus farms in Serbia. J. Environ. Sci. Health B 2015, 50, 607e613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potočnik, I.; Todorović, B.; Đurović-Pejčev, R.; Stepanović, M.; Rekanović, E.; Milijašević-Marčić, S. Antimicrobial activity of biochemical substances against pathogens of cultivated mushrooms in Serbia. Pestic. Phytomed. 2016, 31, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potočnik, I.; Rekanović, E.; Todorović, B.; Luković, J.; Paunović, D.; Stanojević, O.; Milijašević-Marčić, S. The effects of casing soil treatment with Bacillus subtilis Ch-13 biofungicide on green mould control and mushroom yield. Pestic. Phytomed. 2019, 34, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandin, C.; Védie, R.; Rousseau, T.; Le Coq, D.; Aymerich, S.; Briandet, R. Dynamics of compost microbiota during the cultivation of Agaricus bisporus in the presence of Bacillus velezensis QST713 as biocontrol agent against Trichoderma aggressivum. Biol. Control 2018, 127, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandin, C.; Le Coq, D.; Deschamps, J.; Védie, R.; Rousseau, T.; Aymerich, S.; Briandet, R. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus velezensis QST713: A biocontrol agent that protects Agaricus bisporus crops against the green mould disease. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 278, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, J.; García-Delgado, C.; Lavega, R.; Tello, M.L.; De Toro, M.; Barba-Vicente, V.; Rodríguez-Cruz, M.S.; Sánchez-Martín, M.J.; Pérez, M.; Preston, G.M. Holistic assessment of the microbiome dynamics in the substrates used for commercial champignon (Agaricus bisporus) cultivation. Microb. Biotechnol. 2020, 13, 1933–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, F.R.; Pecchia, J.A.; Segato, F.; Polikarpov, I. Exploring oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) substrate preparation by varying phase I composting time: Changes in bacterial communities and physicochemical composition of biomass impacting mushroom yields. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 126, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, R.L.; Kalkhove, S.I.C.; Lugones, L.G.; Baars, J.J.P.; Wösten, H.A.B.; Bakker, P.A.H.M. Effects of fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. isolated from mushroom cultures on Lecanicillium fungicola. Biol. Control 2012, 63, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]