Assessing the Use of Molecular Barcoding and qPCR for Investigating the Ecology of Prorocentrum minimum (Dinophyceae), a Harmful Algal Species

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

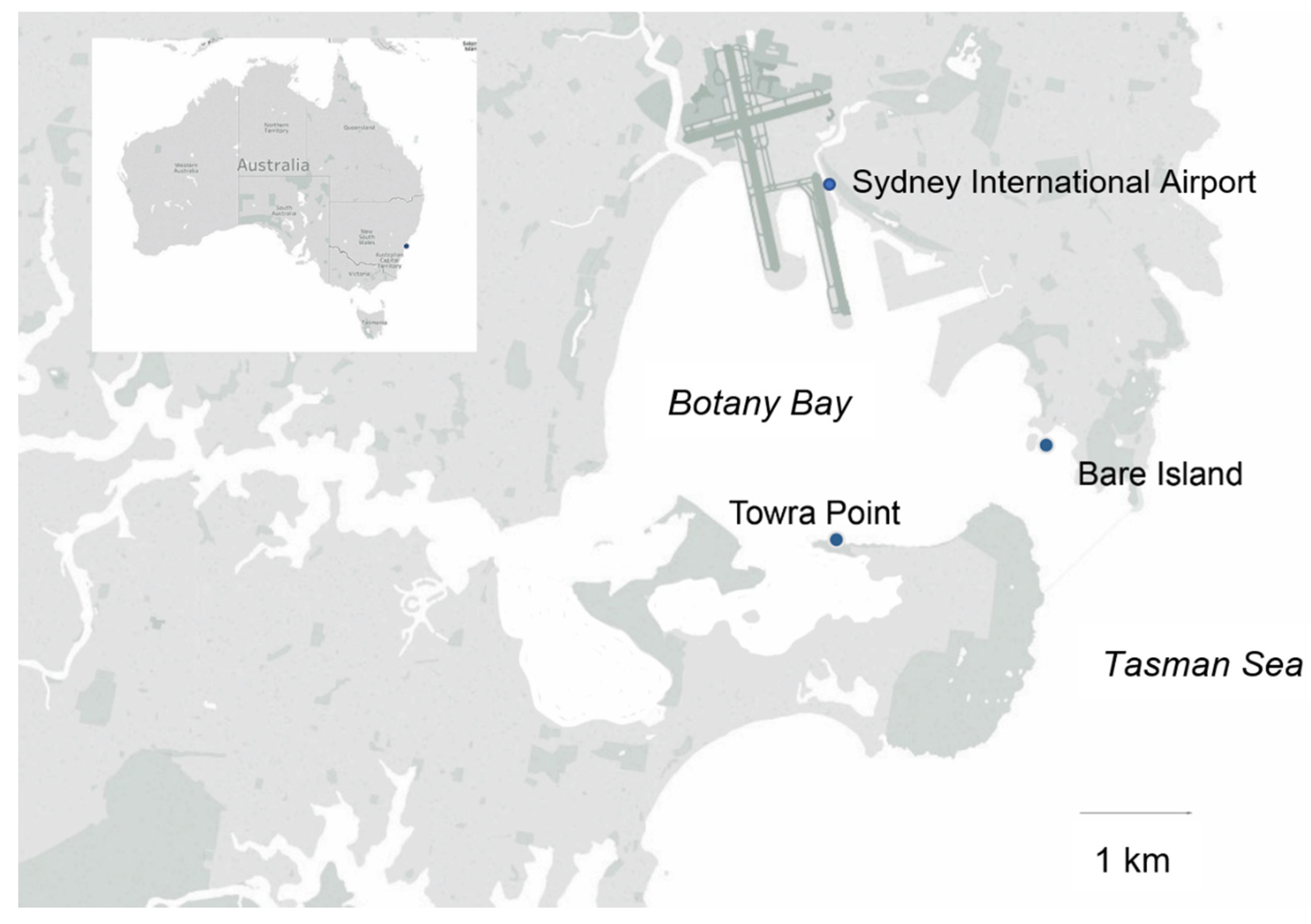

2.1. Sampling Sites

2.2. Sampling, DNA Extraction for Amplicon Sequencing, Metabarcoding, and Physico-Chemical Data

2.3. Cell Culture and Culturing Conditions

2.4. Toxin Analysis

2.5. DNA Extraction and PCR for Strain Identification

2.6. qPCR Assay Development

2.6.1. Primer Design

2.6.2. qPCR Assays

2.7. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.8. Environmental Parameters

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Strain Isolation, Identification, and Toxin Testing

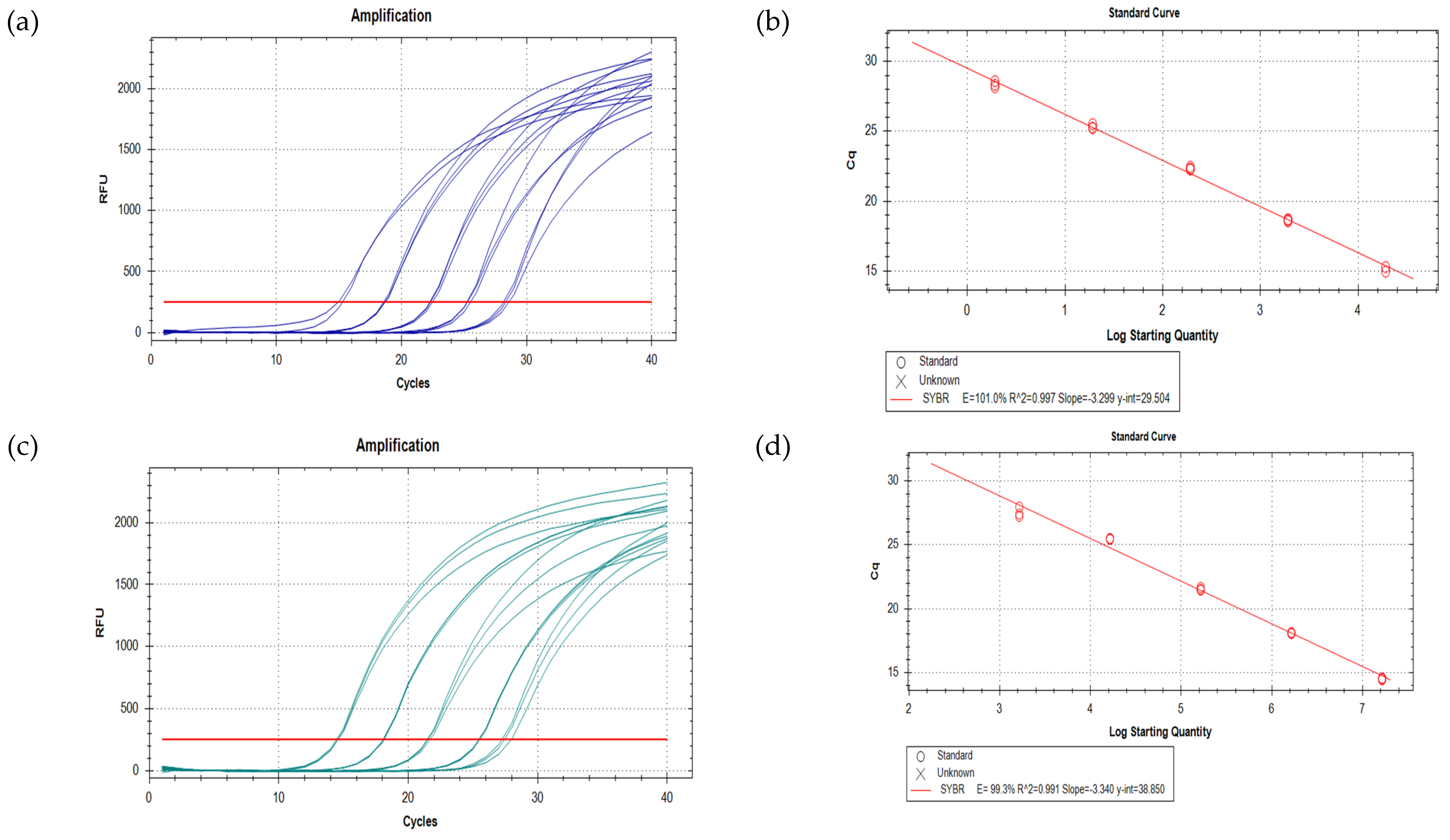

3.2. qPCR Assay Development and Testing

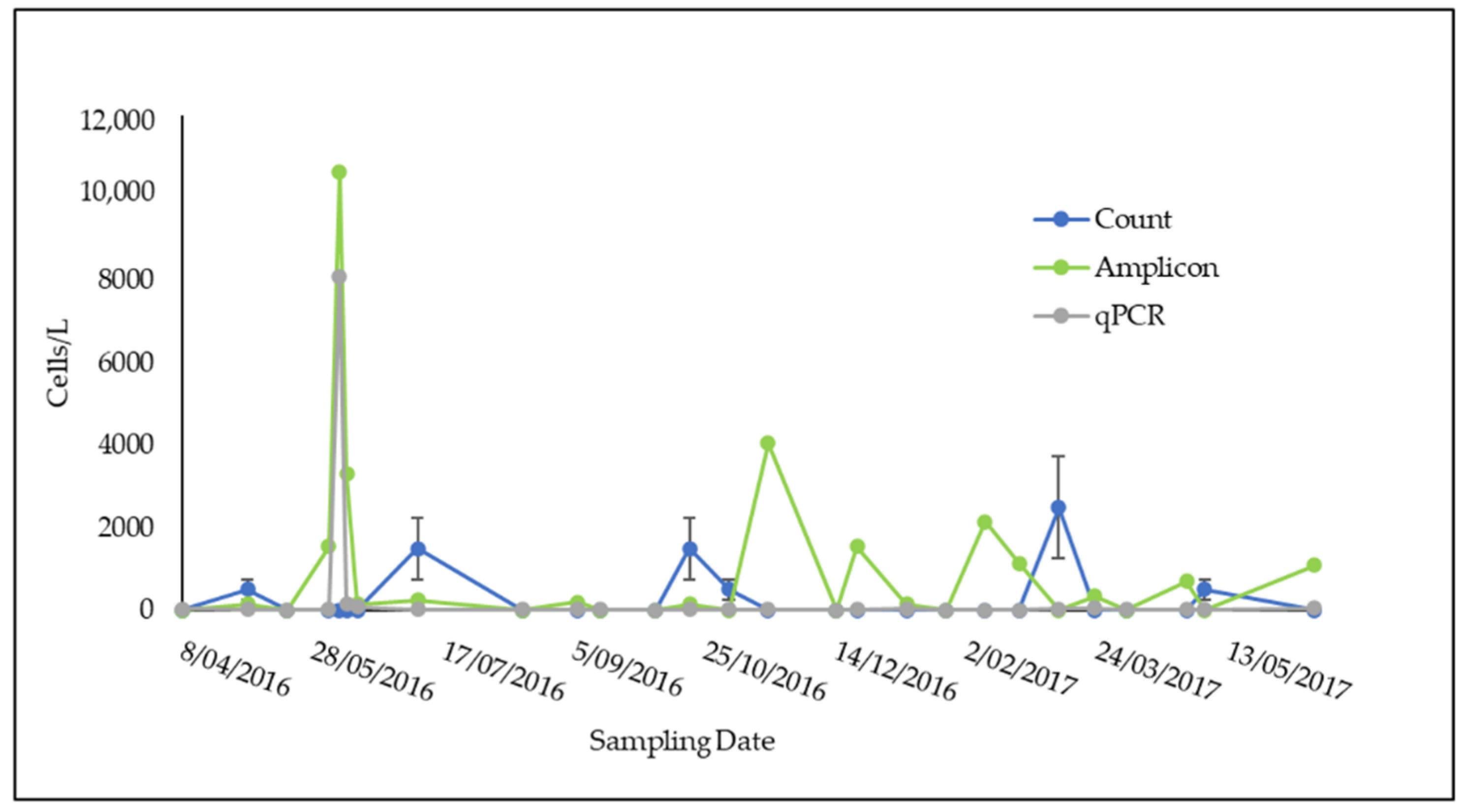

3.3. Comparison of qPCR, Light Microscope Count, and Amplicon Sequencing Abundance Results

3.4. Amplicon Sequencing Results

3.5. Factors Influencing the Growth of P. minimum in Botany Bay

Co-occurrence Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heil, C.A.; Glibert, P.M.; Fan, C. Prorocentrum minimum (Pavillard) Schiller: A review of a harmful algal bloom species of growing worldwide importance. Harmful Algae 2005, 4, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobler, C.J.; Doherty, O.M.; Hattenrath-Lehmann, T.K.; Griffith, A.W.; Kang, Y.; Litaker, R.W. Ocean warming since 1982 has expanded the niche of toxic algal blooms in the North Atlantic and North Pacific oceans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 4975–4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, S.W. Coastal marine eutrophication: A definition, social causes, and future concerns. Ophelia 1995, 41, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloern, J.E. Our evolving conceptual model of the coastal eutrophication problem. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2001, 210, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménesguen, A.; Lacroix, G. Modelling the marine eutrophication: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018.

- Glibert, P.M.; Mayorga, E.; Seitzinger, S. Prorocentrum minimum tracks anthropogenic nitrogen and phosphorus inputs on a global basis: Application of spatially explicit nutrient export models. Harmful Algae 2008, 8, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdu, S.; Pertola, S.; Kuosa, H. Prorocentrum minimum (Dinophyceae) in the Baltic Sea: Morphology, occurrence—A review. Harmful Algae 2005, 4, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertola, S.; Kuosa, H.; Olsonen, R. Is the invasion of Prorocentrum minimum (Dinophyceae) related to the nitrogen enrichment of the Baltic Sea? Harmful Algae 2005, 4, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlato, S.; Telesh, I.; Mantnaseva, O.; Pozdnyakov, I.; Berdieva, M.; Schubert, H.; Filatova, N.; Knyazev, N.; Pechkovskaya, S. Studies of bloom-forming dinoflagellates Prorocentrum minimum in fluctuating environment: Contribution to aquatic ecology, cell biology and invasion theory. Protistology 2018, 12, 113–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajani, P.A.; Larsson, M.E.; Woodcock, S.; Rubio, A.; Farrell, H.; Brett, S.; Murray, S.A. Bloom drivers of the potentially harmful dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum (Pavillard) Schiller in a south eastern temperate Australian estuary. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 215, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisler, J.; Glibert, P.; Burkholder, J.; Anderson, D.; Cochlan, W.; Dennison, W.; Gobler, C.; Dortch, Q.; Heil, C.; Humphries, E.; et al. Eutrophication and Harmful Algal Blooms: A Scientific Consensus. Harmful Algae 2008, 8, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, B.; Jeong, E.-S.; Malazarte, J.M.; Sin, Y. Physiological and Molecular Response of Prorocentrum minimum to Tannic Acid: An Experimental Study to Evaluate the Feasibility of Using Tannic Acid in Controling the Red Tide in a Eutrophic Coastal Water. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajdu, S.; Edler, L.; Olenina, I.; Witek, B. Spreading and Establishment of the Potentially Toxic DinoflagellateProrocentrum minimum in the Baltic Sea. Int. Rev. Hydrobiol. 2000, 85, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telesh, I.; Schubert, H.; Skarlato, S.O. Ecological niche partitioning of the invasive dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum and its native congeners in the Baltic Sea. Harmful Algae 2016, 59, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tango, P.J.; Magnien, R.; Butler, W.; Luckett, C.; Luckenbach, M.; Lacouture, R.; Poukish, C. Impacts and potential effects due to Prorocentrum minimum blooms in Chesapeake Bay. Harmful Algae 2005, 4, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, M.A.; Seliger, H.H. Selection for a red tide organism: Physiological responses to the physical environment1,2. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1981, 26, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoecker, D.; Li, A.; Coats, D.; Gustafson, D.; Nannen, M. Mixotrophy in the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1997, 152, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denardou-Queneherve, A.; Grzebyk, D.; Pouchus, Y.; Sauviat, M.; Alliot, E.; Biard, J.; Berland, B.; Verbist, J. Toxicity of French strains of the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum experimental and natural contaminations of mussels. Toxicon 1999, 37, 1711–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzebyk, D.; Denardou, A.; Berland, B.; Pouchus, Y.F. Evidence of a new toxin in the red-tide dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum. J. Plankton Res. 1997, 19, 1111–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langeland, G.; Hasselgård, T.; Tangen, K.; Skulberg, O.M.; Hjelle, A. An outbreak of paralytic shellfish poisoning in western Norway. Sarsia 1984, 69, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangen, K. Shellfish poisoning and the ocurrence of potentially toxic dinoflagellates in Norwegian waters. Sarsia 1983, 68, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsberg, J.H. The Effects of Harmful Algal Blooms on Aquatic Organisms. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2002, 10, 113–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikfors, G. A review and new analysis of trophic interactions between Prorocentrum minimum and clams, scallops, and oysters. Harmful Algae 2005, 4, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogburn, D.; Callinan, R.; Pearce, I.; Hallegraeff, G.; Landos, M. Investigation and Management of a Major Oyster Mortality Event in Wonboyn Lake, Australia. In Diseases in Asian Aquaculture; Walker, P., Lester, R., Bondad-Reantaso, M.G., Eds.; Asian Fisheries Society: Manila, Philippines, 2005; pp. 301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, I.; Alfonso, A.; Alonso, E.; Rubiolo, J.A.; Roel, M.; Vlamis, A.; Katikou, P.; Jackson, S.A.; Menon, M.L.; Dobson, A.; et al. The association of bacterial C9-based TTX-like compounds with Prorocentrum minimum opens new uncertainties about shellfish seafood safety. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlamis, A.; Katikou, P.; Rodriguez, I.; Rey, V.; Alfonso, A.; Papazachariou, A.; Zacharaki, T.; Botana, A.; Botana, L.; Vlamis, A.; et al. First Detection of Tetrodotoxin in Greek Shellfish by UPLC-MS/MS Potentially Linked to the Presence of the Dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum. Toxins 2015, 7, 1779–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.S.; Guo, R.; Lim, W.-A.; Ki, J.-S. Importance of free-living and particle-associated bacteria for the growth of the harmful dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum: Evidence in culture stages. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2018, 69, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäki, A.; Salmi, P.; Mikkonen, A.; Kremp, A.; Tiirola, M. Sample Preservation, DNA or RNA Extraction and Data Analysis for High-Throughput Phytoplankton Community Sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellner, K.G.; Doucette, G.J.; Kirkpatrick, G.J. Harmful algal blooms: Causes, impacts and detection. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 30, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlin, L. Molecular tools for monitoring harmful algal blooms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 6683–6685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefterova, M.I.; Budvytiene, I.; Sandlund, J.; Färnert, A.; Banaei, N. Simple Real-Time PCR and Amplicon Sequencing Method for Identification of Plasmodium Species in Human Whole Blood. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 2251–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlin, L.; Orozco, J. Molecular Techniques for the Detection of Organisms in Aquatic Environments, with Emphasis on Harmful Algal Bloom Species. Sensors 2017, 17, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudela, R.M.; Howard, M.D.A.; Jenkins, B.D.; Miller, P.E.; Smith, G.J. Using the molecular toolbox to compare harmful algal blooms in upwelling systems. Prog. Oceanogr. 2010, 85, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, D.C.; Coghlan, M.L.; Bunce, M. From Benchtop to Desktop: Important Considerations when Designing Amplicon Sequencing Workflows. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, R.F.; Horak, A.; Andrew, R.L.; Coffroth, M.-A.; Andersen, R.A.; Küpper, F.C.; Jameson, I.; Hoppenrath, M.; Véron, B.; Kasai, F.; et al. Environmental barcoding reveals massive dinoflagellate diversity in marine environments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L.; Bertozzini, E.; Penna, A.; Perini, F.; Garcés, E.; Magnani, M. Analysis of rRNA gene content in the Mediterranean dinoflagellate Alexandrium catenella and Alexandrium taylori: Implications for the quantitative real-time PCR-based monitoring methods. J. Appl. Phycol. 2010, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godhe, A.; Asplund, M.E.; Härnström, K.; Saravanan, V.; Tyagi, A.; Karunasagar, I. Quantification of diatom and dinoflagellate biomasses in coastal marine seawater samples by real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 7174–7182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachvaroff, T.R.; Place, A.R. From Stop to Start: Tandem Gene Arrangement, Copy Number and Trans-Splicing Sites in the Dinoflagellate Amphidinium carterae. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krehenwinkel, H.; Wolf, M.; Lim, J.Y.; Rominger, A.J.; Simison, W.B.; Gillespie, R.G. Estimating and mitigating amplification bias in qualitative and quantitative arthropod metabarcoding. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, I.M.; Pinto, A.J.; Guest, J.S. Design and Evaluation of Illumina MiSeq-Compatible, 18S rRNA Gene-Specific Primers for Improved Characterization of Mixed Phototrophic Communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 5878–5891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Microbiome–Australian Microbiome. Available online: https://www.australianmicrobiome.com/ (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Ajani, P.; Brett, S.; Krogh, M.; Scanes, P.; Webster, G.; Armand, L. The risk of harmful algal blooms (HABs) in the oyster-growing estuaries of New South Wales, Australia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 5295–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelkerling, W.J.; Kowal, R.R.; Gough, S.B. Sedgwick-rafter cell counts: A procedural analysis. Hydrobiologia 1976, 48, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throndsen, J. Preservation and storage. In Phytoplankton Manual; Sournia, A., Ed.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1978; pp. 69–74. ISBN 9231015729. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Kamp, J.; Mazard, S. Coastal Seawater Sampling for Australian Coastal Microbial Observatory Network. In Australian Microbiome Methods; Bioplatforms Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2020; pp. 12–18. Available online: https://www.australianmicrobiome.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/AM_Methods_for_metadata_fields_18012021_V1.2.3.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- Keller, M.D.; Selvin, R.C.; Claus, W.; Guillard, R.R.L. Media for the culture of oceanic ultraphytoplankton. J. Phycol. 2007, 23, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, S.W.; LeRoi, J.M. Simple procedures for growing SCOR reference microalgal cultures. In Phytoplankton Pigments in Oceanography: Monographs on Oceanographic Methodology; Jeffrey, S.W., Mantoura, R.F.C., Wright, S.W., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1997; pp. 181–205. ISBN 9231032755. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood, T.; Boundy, M.; Selwood, A.; Ginkel, R.; MacKenzie, L.; McNabb, P. Refinement and implementation of the Lawrence method (AOAC 2005.06) in a commercial laboratory: Assay performance during an Alexandrium catenella bloom event. Harmful Algae 2013, 24, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc. T100TM Thermal Cycler. Available online: https://www.bio-rad.com/en-au/product/t100-thermal-cycler?ID=LGTWGIE8Z (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Handy, S.M.; Demir, E.; Hutchins, D.A.; Portune, K.J.; Whereat, E.B.; Hare, C.E.; Rose, J.M.; Warner, M.; Farestad, M.; Cary, S.C.; et al. Using quantitative real-time PCR to study competition and community dynamics among Delaware Inland Bays harmful algae in field and laboratory studies. Harmful Algae 2008, 7, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc. CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System. Available online: https://www.bio-rad.com/en-au/product/cfx96-touch-real-time-pcr-detection-system?ID=LJB1YU15 (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.C.; Nadeau, K.; Abbasi, M.; Lachance, C.; Nguyen, M.; Fenrich, J. The Ultimate qPCR Experiment: Producing Publication Quality, Reproducible Data the First Time. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larionov, A.; Krause, A.; Miller, W. A standard curve based method for relative real time PCR data processing. BMC Bioinform. 2005, 6, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadziavdic, K.; Lekang, K.; Lanzen, A.; Jonassen, I.; Thompson, E.M.; Troedsson, C. Characterization of the 18S rRNA gene for designing universal eukaryote specific primers. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioplatforms Australia. Protocol for 18S rRNA Amplification and Sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq; Bioplatforms Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral-Zettler, L.; Bauer, M.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Betley, J.; Caporaso, J.G.; Ducklow, H.W.; Fierer, N.; Fraser, L.; Gilbert, J.A.; Gormley, N.; et al. EMP 18S Illumina Amplicon Protocol.; Earth Microbiome Project. Available online: https://earthmicrobiome.org/protocols-and-standards/18s/ (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- Guillou, L.; Bachar, D.; Audic, S.; Bass, D.; Berney, C.; Bittner, L.; Boutte, C.; Burgaud, G.; de Vargas, C.; Decelle, J.; et al. The Protist Ribosomal Reference database (PR2): A catalog of unicellular eukaryote Small Sub-Unit rRNA sequences with curated taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D597–D604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croux, C.; Dehon, C. Influence functions of the Spearman and Kendall correlation measures. Stat. Methods Appt. 2010, 19, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.M.; Veech, J.A.; Marsh, C.J. cooccur: Probabilistic Species Co-Occurrence Analysis in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2016, 69, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Veech, J.A. A probabilistic model for analysing species co-occurrence. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2013, 22, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.J.; Nedwell, D.B.; Dong, L.F.; Osborn, A.M. Evaluation of quantitative polymerase chain reaction-based approaches for determining gene copy and gene transcript numbers in environmental samples. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 8, 804–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.J.; Osborn, A.M. Advantages and limitations of quantitative PCR (Q-PCR)-based approaches in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009, 67, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Zhen, Y.; Mi, T.; Yu, Z. Detection of Prorocentrum minimum (Pavillard) Schiller with an Electrochemiluminescence-Molecular Probe Assay. Mar. Biotechnol. (NY) 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, E.S.; Sousa, I. Experimental work on the dinoflagellate toxin production. Arq. Inst. Nac. Saude 1981, 6, 381–387. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.Q.; Gu, X. An ecological study of red tides in the East China Sea. In Toxic Phytoplankton Blooms in the Sea; Smayda, T.J., Shimizu, Y., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Grzebyk, D.; Berland, B. Influences of temperature, salinity and irradiance on growth of Prorocentrum minimum (Dinophyceae) from the Mediterranean Sea. J. Plankton Res. 1996, 18, 1837–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, D.C.; Bunce, M.; Cannell, B.L.; Oliver, R.; Houston, J.; White, N.E.; Barrero, R.A.; Bellgard, M.I.; Haile, J. DNA-Based Faecal Dietary Analysis: A Comparison of qPCR and High Throughput Sequencing Approaches. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvindy, R.; Bolch, C.J.; MacKenzie, L.; Smith, K.F.; Murray, S.A. qPCR Assays for the Detection and Quantification of Multiple Paralytic Shellfish Toxin-Producing Species of Alexandrium. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svec, D.; Tichopad, A.; Novosadova, V.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Kubista, M. How good is a PCR efficiency estimate: Recommendations for precise and robust qPCR efficiency assessments. Biomol. Detect. Quantif. 2015, 3, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontanis, E.J.; Reed, F.A. Evaluation of Real-Time PCR Amplification Efficiencies to Detect PCR Inhibitors. J. Forensic Sci. 2006, 51, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, S.; Flø Jørgensen, M.; Ho, S.Y.W.; Patterson, D.J.; Jermiin, L.S. Improving the Analysis of Dinoflagellate Phylogeny based on rDNA. Protist 2005, 156, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litaker, R.W.; Vandersea, M.W.; Kibler, S.R.; Reece, K.S.; Stokes, N.A.; Lutzoni, F.M.; Yonish, B.A.; West, M.A.; Black, M.N.D.; Tester, P.A. Recognizing dinoflagellate species using ITS rRNA sequences. J. Phycol. 2007, 43, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andree, K.B.; Fernández-Tejedor, M.; Elandaloussi, L.M.; Quijano-Scheggia, S.; Sampedro, N.; Garcés, E.; Camp, J.; Diogène, J. Quantitative PCR coupled with melt curve analysis for detection of selected Pseudo-nitzschia spp. (Bacillariophyceae) from the northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 1651–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winder, L.; Phillips, C.; Richards, N.; Ochoa-Corona, F.; Hardwick, S.; Vink, C.J.; Goldson, S. Evaluation of DNA melting analysis as a tool for species identification. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2011, 2, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.; Huggett, J. qPCR primer design revisited. Biomol. Detect. Quantif. 2017, 14, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, W.J.; García-Robledo, C.; Uriarte, M.; Erickson, D.L. DNA barcodes for ecology, evolution, and conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godhe, A.; Cusack, C.; Pedersen, J.; Andersen, P.; Anderson, D.M.; Bresnan, E.; Cembella, A.; Dahl, E.; Diercks, S.; Elbrächter, M.; et al. Intercalibration of classical and molecular techniques for identification of Alexandrium fundyense (Dinophyceae) and estimation of cell densities. Harmful Algae 2007, 6, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bescot, N.; Mahé, F.; Audic, S.; Dimier, C.; Garet, M.J.; Poulain, J.; Wincker, P.; de Vargas, C.; Siano, R. Global patterns of pelagic dinoflagellate diversity across protist size classes unveiled by metabarcoding. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 609–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.F.; Kohli, G.S.; Murray, S.A.; Rhodes, L.L. Assessment of the metabarcoding approach for community analysis of benthic-epiphytic dinoflagellates using mock communities. New Zeal. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2017, 51, 555–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Bunge, J.; Leslin, C.; Jeon, S.; Epstein, S.S. Polymerase chain reaction primers miss half of rRNA microbial diversity. ISME J. 2009, 3, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajani, P.A.; Hallegraeff, G.M.; Allen, D.; Coughlan, A.; Richardson, A.J.; Armand, L.K.; Ingleton, T.; Murray, S.A. Establishing Baselines: Eighty Years of Phytoplankton Diversity and Biomass in South- Eastern Australia. In Oceanography and Marine Biology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 395–420. [Google Scholar]

- Ajani, P.A.; Allen, A.P.; Ingleton, T.; Armand, L.K. A decadal decline in relative abundance and a shift in microphytoplankton composition at a long-term coastal station off southeast Australia. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2014, 59, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macheriotou, L.; Guilini, K.; Bezerra, T.N.; Tytgat, B.; Nguyen, D.T.; Phuong Nguyen, T.X.; Noppe, F.; Armenteros, M.; Boufahja, F.; Rigaux, A.; et al. Metabarcoding free-living marine nematodes using curated 18S and CO1 reference sequence databases for species-level taxonomic assignments. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 1211–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boers, S.A.; Jansen, R.; Hays, J.P. Understanding and overcoming the pitfalls and biases of next-generation sequencing (NGS) methods for use in the routine clinical microbiological diagnostic laboratory. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 1059–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pochon, X.; Bott, N.J.; Smith, K.F.; Wood, S.A. Evaluating detection limits of next-generation sequencing for the surveillance and monitoring of international marine pests. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, G.S.; Neilan, B.A.; Brown, M.V.; Hoppenrath, M.; Murray, S.A. Cob gene pyrosequencing enables characterization of benthic dinoflagellate diversity and biogeography. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Penna, A.; Bertozzini, E.; Vila, M.; Garces, E.; Magnani, M. Development of a Real-Time PCR Assay for Rapid Detection and Quantification of Alexandrium minutum (a Dinoflagellate). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.L.-A. Metagenomic Amplicon Sequencing as a Rapid and High-Throughput Tool for Aquatic Biodiversity Surveys; University of Adelaide: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Penna, A.; Galluzzi, L. The quantitative real-time PCR applications in the monitoring of marine harmful algal bloom (HAB) species. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2013, 20, 6851–6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxinos, R. A rapid Utermohl method for estimating algal numbers. J. Plankton Res. 2000, 22, 2255–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.A.; Ruvindy, R.; Kohli, G.S.; Anderson, D.M.; Brosnahan, M.L. Evaluation of sxtA and rDNA qPCR assays through monitoring of an inshore bloom of Alexandrium catenella Group 1. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engesmo, A.; Strand, D.; Gran-Stadniczeñko, S.; Edvardsen, B.; Medlin, L.K.; Eikrem, W. Development of a qPCR assay to detect and quantify ichthyotoxic flagellates along the Norwegian coast, and the first Norwegian record of Fibrocapsa japonica (Raphidophyceae). Harmful Algae 2018, 75, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loveless, A.M. A multi-dimensional receiving water quality model for Botany Bay (Sydney, Australia). In Proceedings of the 18th World IMACS/MODSIM Congress, Cairns, Australia, 13–17 July 2009; pp. 4170–4176. [Google Scholar]

- DECCW. Towra Point Nature Reserve Ramsar Site; DECCW: Sydney, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ajani, P.; Ingleton, T.; Pritchard, T.; Armand, L. Microalgal Blooms in the Coastal Waters of New South Wales, Australia. Proc. Linn. Soc. New South. Wales 2011, 133, 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, F.X.; Zhang, Y.; Warner, M.E.; Feng, Y.; Sun, J.; Hutchins, D.A. A comparison of future increased CO2 and temperature effects on sympatric Heterosigma akashiwo and Prorocentrum minimum. Harmful Algae 2008, 7, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlato, S.; Filatova, N.; Knyazev, N.; Berdieva, M.; Telesh, I. Salinity stress response of the invasive dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 211, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, T.; Vidussi, F.; Mas, S.; Parin, D.; Simier, M.; Mostajir, B. Water temperature drives phytoplankton blooms in coastal waters. PLoS ONE 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collos, Y. Time-lag algal growth dynamics: Biological constraints on primary production in aquatic environments. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1986, 33, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguera, B.; Velo-Suárez, L.; Raine, R.; Park, M.G. Harmful Dinophysis species: A review. Harmful Algae 2012, 14, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M.; Alpermann, T.J.; Cembella, A.D.; Collos, Y.; Masseret, E.; Montresor, M. The globally distributed genus Alexandrium: Multifaceted roles in marine ecosystems and impacts on human health. Harmful Algae 2012, 14, 10–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yu, R.C.; Chen, J.H.; Zhang, Q.C.; Kong, F.Z.; Zhou, M.J. Distribution of Alexandrium fundyense and A. pacificum (Dinophyceae) in the Yellow Sea and Bohai Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 96, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.H.; Li, Z.; Kim, E.S.; Park, J.-W.; Lim, W.A. Which species, Alexandrium catenella (Group I) or A. pacificum (Group IV), is really responsible for past paralytic shellfish poisoning outbreaks in Jinhae-Masan Bay, Korea? Harmful Algae 2017, 68, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Sequence (Forward) | Name | Sequence (Reverse) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer Sequences for qPCR | |||

| Pm 200F | TGTGTTTATTAGTTACAGAACCAGC | Pm 525R | AATTCTACTCATTCCAATTACAAGACAAT |

| 1F Pmin | CGCAGCGAAGTGTGATAAGC | 1R Pmin | TCTGGAAAGGCCAGAAGCTG |

| 2F Pmin | TCGGCTCGAACAACGATGAA | 2R Pmin | AAGCGTTCTGGAAAGGCCAG |

| 3F Pmin | TTCTGGCCTTTCCAGAACGC | 3R Pmin | CATGCCCAACAACAAGGCAA |

| 4F Pmin | CGTATACTGCGCTTTCGGGA | 4R Pmin | CACACAGAAACACACAAGCGT |

| 5F Pmin | CCTTTCCAGAACGCTTGTGTG | 5R Pmin | CTGGGCACTAGACAGCAAGG |

| 6F Pmin | CAGGCTCAGACCGTCTTCTG | 6R Pmin | AGCGTTCTGGAAAGGCCAG |

| 7F Pmin | CAACAGTTGGTGAGGCTCT | 7R Pmin | ATTCAAAAACACAGAAGATCAGGAA |

| 8F Pmin | AACAACAGTTGGTGAGGCTCTG | 8R Pmin | CAAAAACACAGAAGATCAGGAAGAC |

| 9F Pmin | GTGAGGCTCTGGGTGGG | 9R Pmin | CAAAAACACAGAAGATCAGGAAGAC |

| 10F Pmin | TCATTCGCACGCATCCATTC | 10R Pmin | AAGGACAGGCACAGAAGACG |

| 11F Pmin | TTCAGTGCACAGGGTCTTCC | 11R Pmin | GTCTTGGTAGGAGTGCGCTG |

| 12F Pmin | GCCTTTCCAGAACGCTTGTGT | 12R Pmin | GCTGACCTAACTTCATGTCTTGG |

| 13F Pmin | CGCTTGTGTGTTTCTGTGTG | 13R Pmin | CCATGCCCAACAACAAGGC |

| 14F Pmin | TCTTCCCACGCAAGCAACT | 14R Pmin | CGGGTTTGCTGACCTAAACT |

| 15F Pmin | ACATTCGCACGCATCCATTC | 15R Pmin | TTGCTGCCCTTGAGTCTCTG |

| 16F Pmin | AACAGTTGGTGAGGCTCTGG | 16R Pmin | AAGGACAGGCACAGAAGACG |

| 17F Pmin | ACAACAGTTGGTGAGGCTCT | 17R Pmin | TTGCTGCCCTTGAGTCTCTG |

| 18F Pmin | CAGTTGGTGAGGCTCTGGG | 18R Pmin | CAGAAGACGGTCTGAGCCTG |

| 19F Pmin | TTCAGTGCACAGGGTCTTCC | 19R Pmin | CATGCCCAACAACAAGGCAA |

| 20F Pmin | ATTCCAGCTTCTGGCCTGTC | 20R Pmin | TAGTTGCTTGCGTGGGAAGA |

| 21F Pmin | CTGTCCAGAACGCTTGTGTG | 21R Pmin | CTTCTAGTTGCTTGCGTGGG |

| 22F Pmin | TTCCCACGCAAGCAACTAGA | 22R Pmin | GCACTAGACAGCAAGGCCA |

| Primer Sequences for Amplicon Sequencing | |||

| Modified TAReuk454FWD1 | CCAGCASCYGCGGTAATTCC | Modified TAReukREV3 | ACTTTCGTTCTTGATYRATGA |

| Primer Sequences for PCR and Sanger Sequencing | |||

| d1f | ACCCGCTGAATTTAAGCATA | d3b | TCGGAGGGAACCAGCTACTA |

| ITSfwd | TTCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG | ITSrev | ATATGCTTAAATTCAGCGGGT |

| Strain Description | Percent Identity | Accession |

|---|---|---|

| Prorocentrum minimum strain DAB02 28S | 99.66% | KU999985.1 |

| Prorocentrum minimum strain D-127 | 99.66% | JX402086.1 |

| Prorocentrum minimum isolate PIPV-1 | 99.54% | JQ616823.1 |

| Prorocentrum minimum isolate SERC | 99.54% | EU780639.1 |

| Prorocentrum minimum strain Pmin1 | 99.54% | AY863004.1 |

| Strain Description | Percent Identity | Accession |

|---|---|---|

| Prorocentrum minimum strain D-127 | 99.67% | JX402086.1 |

| Prorocentrum minimum strain AND3V | 100.00% | EU244473.1 |

| Prorocentrum minimum isolate PIPV-1 | 99.35% | JQ616823.1 |

| Prorocentrum minimum strain PMDH01 | 99.35% | DQ054538.1 |

| Prorocentrum minimum strain NMBjah049 | 99.67% | KY290717.1 |

| Species Name | Culture Collection | Strain ID # |

|---|---|---|

| Prorocentrum cf. balticum | Cawthron Culture Collection (CICCM) | CAWD38 |

| Prorocentrum cassubicum | Australian National Culture Collection (ANAAC) | CS-881 |

| Prorocentrum concavum | Seafood Safety Team, University of Technology Sydney (UTS) | Pmona (SM46) |

| Prorocentrum lima | Seafood Safety Team, University of Technology, Sydney (UTS) | SM43 |

| Specificity | Efficiency | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primer Set | P. minimum | P. cf. balticum | P. cassubicum | P. concavum | P. lima | gBlock (%) | P. min DNA (%) |

| Pm 200F/525R | + | + | − | / | / | 70 | − |

| 3 | + | / | − | − | − | 65 | − |

| 4 | + | + | − | − | − | 64 | − |

| 5 | + | + | + | + | − | 62 | − |

| 6 | + | + | + | + | + | 65 | − |

| 7 | + | / | − | − | − | 57 | − |

| 8 | + | + | − | − | − | 56 | − |

| 9 | + | + | − | − | − | 58 | − |

| 10 | + | + | N/A | / | / | 60 | − |

| 11 | + | − | N/A | − | − | 76 | − |

| 12 | + | / | N/A | / | − | 85 | − |

| 13 | + | − | + | N/A | + | 43 | − |

| 15 | + | + | N/A | + | + | 328 | 335 |

| 19 | + | + | N/A | + | + | 220 | 383 |

| 20 | + | / | − | / | / | 99 | 101 |

| 21 | + | + | + | + | + | N/A | N/A |

| 22 | + | + | + | + | + | 115 | 147 |

| qPCR vs. Amplicon Sequencing | qPCR vs. Count | Amplicon Sequencing vs. Count | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple R | 0.90 | 0.18 | 0.23 |

| R2 | 0.82 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.81 | −0.02 | 0.00 |

| Standard Error | 1172.31 | 670.05 | 662.94 |

| df | 35 | 20 | 20 |

| p (Significance) | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.31 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McLennan, K.; Ruvindy, R.; Ostrowski, M.; Murray, S. Assessing the Use of Molecular Barcoding and qPCR for Investigating the Ecology of Prorocentrum minimum (Dinophyceae), a Harmful Algal Species. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9030510

McLennan K, Ruvindy R, Ostrowski M, Murray S. Assessing the Use of Molecular Barcoding and qPCR for Investigating the Ecology of Prorocentrum minimum (Dinophyceae), a Harmful Algal Species. Microorganisms. 2021; 9(3):510. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9030510

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcLennan, Kate, Rendy Ruvindy, Martin Ostrowski, and Shauna Murray. 2021. "Assessing the Use of Molecular Barcoding and qPCR for Investigating the Ecology of Prorocentrum minimum (Dinophyceae), a Harmful Algal Species" Microorganisms 9, no. 3: 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9030510

APA StyleMcLennan, K., Ruvindy, R., Ostrowski, M., & Murray, S. (2021). Assessing the Use of Molecular Barcoding and qPCR for Investigating the Ecology of Prorocentrum minimum (Dinophyceae), a Harmful Algal Species. Microorganisms, 9(3), 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9030510