Abstract

Lactobacillus acidophilus is one of the most commonly used industrial products worldwide. Since its probiotic efficacy is strain-specific, the identification of probiotics at both the species and strain levels is necessary. However, neither phenotypic nor conventional genotypic methods have enabled the effective differentiation of L. acidophilus strains. In this study, a whole-genome sequence-based analysis was carried out to establish high-resolution strain typing of 41 L. acidophilus strains (including commercial isolates and reference strains) using the cano-wgMLST_BacCompare analytics platform; consequently, a strain-specific discrimination method for the probiotic strain LA1063 was developed. Using a core-genome multilocus sequence-typing (cgMLST) scheme based on 1390 highly conserved genes, 41 strains could be assigned to 34 sequence types. Subsequently, we screened a set of 92 loci with a discriminatory power equal to that of the 1390 loci cgMLST scheme. A strain-specific polymerase chain reaction combined with a multiplex minisequencing method was developed based on four (phoU, secY, tilS, and uvrA_1) out of 21 loci, which could be discriminated between LA1063 and other L. acidophilus strains using the cgMLST data. We confirmed that the strain-specific single-nucleotide polymorphisms method could be used to quickly and accurately identify the L. acidophilus probiotic strain LA1063 in commercial products.

1. Introduction

Lactobacillus acidophilus is a commonly recognized species of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) that can be isolated from animal and human microbiota, such as those of the feces, mouth, and vagina [1,2,3,4]. L. acidophilus strains have been widely used in commercial probiotic products, including cheese, acidophilus milk, and yogurt, as well as in dietary supplements, with reported functional effects [5]. L. acidophilus NCFM is a well-known probiotic strain that is generally recognized as safe by the United States Food and Drug Administration: it improves the human intestinal environment and adjusts the balance of enteric bacteria [6]. The health benefits attributed to probiotic microorganisms are strain-specific [7,8]. Huys et al. [9] indicated that, because of methods that limit taxonomic resolution, more than 28% of commercially available probiotics are incorrectly labeled at the species or genus level. The ability to accurately identify probiotic strains in products is critical for suppliers and manufacturers. Therefore, starter cultures must be identified not only at the species level, but also, at the strain level to manage and control the quality of probiotic products.

Conventional molecular methods for strain typing L. acidophilus, such as randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometry, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), are based on DNA and protein fingerprinting [10,11,12]. Although PFGE is considered the gold standard for bacterial strain typing, the discriminatory power of these methods is insufficient [13]. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) is based on partial nucleotide sequences of multiple housekeeping genes and has been used for Lactobacillus species, including L. delbrueckii, L. fermentum, L. plantarum, L. paracasei, and L. sakei [14,15,16,17,18]. MLST is a suitable alternative to PFGE [19]. Ramachandran et al. [11] reported that the MLST scheme using seven conserved housekeeping genes (fusA, gpmA, gyrA, gyrB, lepA, pyrG, and recA) could be used as an intraspecies subtyping technique for the Lactobacillus complex (L. acidophilus, L. amylovorus, L. crispatus, L. gallinarum, L. gasseri, and L. johnsonii); however, two allelic profiles from five L. acidophilus strains were observed only in the gyrA gene. L. acidophilus strains have been considered to have little genome sequence variation [20,21,22,23], and they are regarded as a monophyletic taxon [10]. Therefore, higher-resolution strain-level differentiation methods must be developed for L. acidophilus strains.

With the technological achievement of whole-genome sequencing (WGS), dry-lab in silico analyses now rely on comparative genome sequences instead of conventional taxonomic methods for deep-level phylogenies [24,25]. Chun et al. [26] proposed minimum standards for species identification on the basis of overall genome-related indices, such as digital DNA‒DNA hybridization (dDDH) values and average nucleotide identity (ANI). By contrast, WGS-based strain typing uses a gene-by-gene approach, such as whole-genome MLST (wgMLST) or core-genome MLST (cgMLST), which entails the use of numerous gene loci to compare genomes [27,28]. These approaches provide resolutions superior to those of current subtyping techniques (including PFGE and multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (MLVA)) because they can discriminate between closely related strains of clinically relevant foodborne pathogens [29,30,31].

In this study, we aimed to develop a high-resolution strain-typing method for L. acidophilus probiotic strains, including a differential cgMLST scheme and a strain-specific detection technique, using comparative genome analyses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. L. acidophilus Strains and Culture Conditions

The 11 reference strains and probiotic strain LA1063 used in this study were obtained from the Bioresource Collection and Research Center (BCRC, Hsinchu, Taiwan), and Synbio Tech Inc., Kaohsiung, Taiwan, respectively, and they were authenticated through 16S rRNA gene sequencing (Supplementary Table S1). Strain LA1063 was isolated from feces of healthy Taiwanese adults and was used as a manufacturing strain for the probiotic supplements. The Lactobacillus strains were incubated anaerobically on Lactobacilli MRS agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) at 37 °C for 36 h, and fresh cultures were used for further DNA analyses.

2.2. WGS and Phylogenomic Metric Calculation

Genomic DNA was extracted using the EasyPrep HY genomic DNA extraction kit (Biotools Co. Ltd., Taipei, Taiwan) following the manufacturer’s protocols. The draft genomes of nine reference strains (BCRC 12255, BCRC 14065, BCRC 14079, BCRC 16092, BCRC 16099, BCRC 17008, BCRC 17481, BCRC 17486, and BCRC 80064) and the probiotic strain LA1063 were sequenced from an Illumina paired-end library with an average insert size of 350 bp by using an Illumina HiSeq4000 platform with the PE 150 strategy at Beijing Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The resulting raw reads were assembled de novo using SOAPdenovo software [32]. A total of 31 public genome sequences of L. acidophilus strains were downloaded from the United States National Center for Biotechnology Information bacterial genome database. Whole-genome similarities among the L. acidophilus strains were estimated using orthologous ANI [33].

2.3. cgMLST Scheme for L. acidophilus Strains

The cano-wgMLST_BacCompare web-based tool [34] was applied to the cgMLST analysis. This platform is composed of two major processes: whole-genome scheme extraction and discriminatory loci refinement. In this pipeline, genes were annotated using Prokka [35], and comparative genomics was performed using Roary [36]. Allele calling was performed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool Type N [37], with a minimum identity of 90% and coverage greater than 90% for the locus assignment (presence/absence profile) and exact match for the allele assignment (allele profile). Genetic relatedness trees were constructed from the allelic profile by using a neighbor-joining clustering algorithm in the Phylogeny Inference Package program [38], FigTree software (v1.4.3) [39], and GrapeTree software (v1.5.0) [40]. Finally, the Environment for the Tree Exploration v3 toolkit [41] and feature importance [42] program from scikit-learn [43] were applied to determine the discriminatory loci.

2.4. Validation of the cgMLST through a Differential MLST Scheme in Reference Strains

The cgMLST analysis results were validated by using an MLST scheme based on the reference strains. In short, by comparing with the sequence of cgMLST loci, the degenerate primers of several differential target genes were designed and tested (Supplementary Table S2). The 11 reference strains were used for validation. Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed using 81 μL of sterile Milli-Q water, 10 μL of 10× PCR buffer, 1.5 μL of denucleoside triphosphates (10 mM), 2.5 μL of forward primer (10 mM), 2.5 μL of reverse primer (10 mM), 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (DreamTaq, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and 3 μL of template DNA (100 ng/μL). The thermal protocol consisted of the following conditions: initial strand denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, 60 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min. The resulting amplicons were purified using a QIA quick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) and sequenced using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle-sequencing kit on a 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems and Hitachi, Foster City, CA, USA). The gene sequences of all strains obtained from sequencing were aligned using the Clustal X program, version 1.8 [44]. The MLST allele profiles and sequence types were analyzed using DnaSP version 5.1 [45].

2.5. Strain-Specific Identification for Probiotic Strain LA1063

The PCR- and single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based discrimination analyses were integrated for the direct strain-specific identification of probiotic strain LA1063. Strain-specific primers were designed using the genes that were chosen based on the presence or absence analysis and the cgMLST allele profiles. The multiplex minisequencing protocol for the analysis of SNPs was performed by following the method described by Huang et al. [46] and Lomonaco et al. [47]. The various concentrations of multiplex PCR and multiplex SNP-specific primers are listed in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. The thermal cycling conditions for the multiple PCR and multiplex minisequencing were as follows: one cycle of 94 °C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 60 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min; one cycle of 72 °C for 7 min; and 25 cycles at 96 °C for 10 s, 50 °C for 5 s, and 60 °C for 1 min.

Table 1.

Multiplex PCR primers designed to direct strain typing for Lactobacillus acidophilus LA1063.

Table 2.

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) primers designed to direct strain typing for Lactobacillus acidophilus LA1063.

2.6. Authentication of Probiotic Strains in Commercial Products by Strain-Specific Assay

Three powder samples from separate batches of LA1063-derived materials for the production of probiotic supplements were analyzed. The LA1063 strain was isolated using serial dilution and plating methods and was identified using a MALDI Microflex LT mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany), as described previously [48], followed by an LA1063 strain-specific assay.

3. Results and Discussion

The genomic data of all L. acidophilus strains had sequences of good quality that were directly reflected in the relatively small number of contigs (median, 24 and interquartile range, 17–34) (Supplementary Table S1), and these data were used in further comparative genomic approaches. Strains had diverse biochemical and phenotypic characteristics. However, high genome similarities among L. acidophilus strains are reported when the sequenced genomes are aligned [10]. This finding was consistent with the high ANI values (≥ 99.3%) among the 41 L. acidophilus strains in our study. In particular, most commercial isolates shared an extremely high degree of genome similarity (approximately 99.9%, Supplementary Figure S1). Comparable genomic conservation levels were previously identified in Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis, for which isolates from dissimilar commercial products had highly conserved genome sequences [49,50].

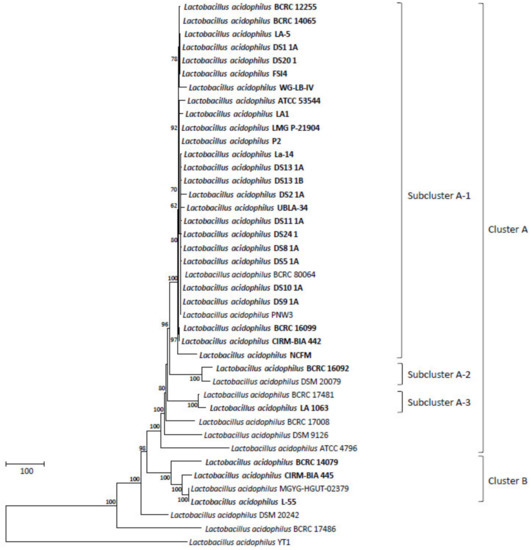

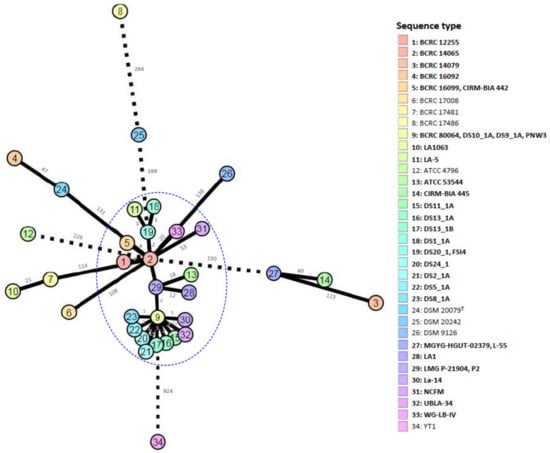

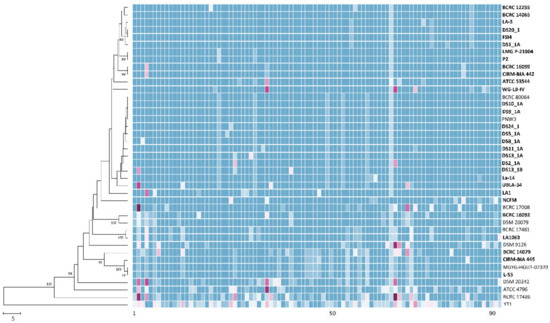

Comparative pan-genome analyses of LAB strains indicated that the health effects of those strains varied among species and strains [51,52,53,54,55]. This variation warrants the genome-level characterization of probiotic strains. A further analysis of genome sequences for high-resolution strain typing of 41 L. acidophilus strains was conducted using the cano-wgMLST_BacCompare analytics platform. For this dataset, the L. acidophilus pan-genome allele database (PGAdb) contained 2603 genes, of which 1390 (53.4%), 687 (26.4%), and 526 (20.2%) were core, accessory, and unique, respectively. Using the cgMLST analysis based on the allele profiles of the 1390 core genes, 38 out of 41 L. acidophilus strains were separated into two clusters, Cluster A (comprising 34 strains) and Cluster B (comprising four strains); moreover, Cluster A was further separated into three subclusters, namely Clusters A-1 (27 strains), A-2 (two strains), and A-3 (two strains), along with three disparate strains. Almost all strains (> 90%) in Cluster A-1 were the commercial strains (Figure 1). A total of 34 different sequence types (STs) were obtained from the 41 strains by using a minimum spanning tree based on the 1390 loci (Supplementary Table S3). Of these, 29 STs were assigned to single strains; four STs (ST5, ST19, ST27, and ST29) were assigned to two strains; and one ST (ST9) was assigned to four strains. A total of 22 out of the 26 STs comprising the commercial strains were grouped into a tight cluster. The differences between the strains within this tight cluster ranged from 0 to 53 alleles (Figure 2). Strain LA1063 showed 21 loci differences from strain BCRC 17481. This result demonstrates the extremely low diversity in commercial isolates and is consistent with the findings of a wgMLST study that used 1815 loci [10]. In addition, we screened a set of the 92 loci with a discriminatory power equal to that of the 1390 loci cgMLST scheme (Figure 3). Detailed information on these loci with high discriminatory powers is provided in Table 3. A differential MLST scheme based on the eight loci of oppA_1, tr, ybhL, frdA, hp, rr, uvrA_2, and phoU genes for 11 reference strains, and one probiotic strain (LA1063) was also used to validate the genome-based analytical data through direct Sanger sequencing. The partial sequences containing the informatic SNPs of the eight differential genes were successfully amplified and sequenced (data not shown) and could be distinguished into different STs, although their lengths were different from those of the WGS in the database (Table 4).

Figure 1.

The allele-based neighbor-joining tree constructed with core-genome multilocus sequence-typing (cgMLST) profiles for the 41 Lactobacillus acidophilus strains on the basis of a comparison of 1390 differentiated core genes. The bold letters indicate commercial isolates. Bar, allele numbers.

Figure 2.

The allele-based minimum spanning tree constructed with cgMLST profiles for the 41 Lactobacillus acidophilus strains on the basis of a comparison of 1390 differentiated core genes. Each circle represents a different sequence type. Branch values indicate the number of loci that differ between nodes.

Figure 3.

The allele-based neighbor-joining tree and heatmap constructed with cgMLST profiles for the 41 Lactobacillus acidophilus strains on the basis of 92 differentiated core genes. The bold letters indicate commercial strains. Different alleles in the same column are indicated by different colors. Bar, allele numbers.

Table 3.

List of the 92 highly discriminatory loci in 41 Lactobacillus acidophilus strains.

Table 4.

Strain typing of 11 reference Lactobacillus acidophilus strains and 1 commercial probiotic strain by multilocus sequence-typing (MLST).

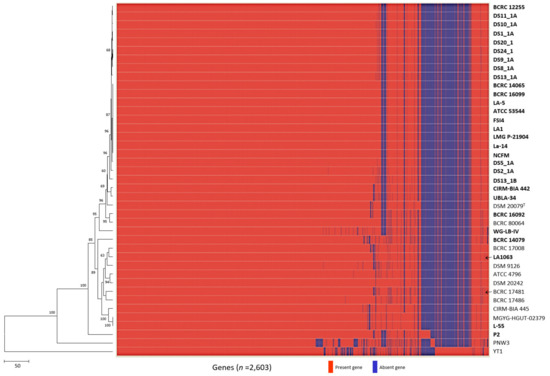

Compared with genome sequence–based typing, a rapid, precise, cost-efficient, and reproducible method for strain identification would be ideal for probiotic starter strains [56,57]. Strain-specific sequences for probiotic strains have been developed mainly by targeting the 16S–23S internal transcribed spacer region, phages, and protein-encoding genes [58,59,60], as well as by using DNA banding patterns [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. However, because these methods have resolution limitations pertaining to monophyletic taxa, strain-specific marker identification can be replaced by a comparative genome analysis that targets unique insertions and deletions (INDELs) or SNPs in DNA sequences [47,69]. Gene presence/absence profiles among L. acidophilus strains were analyzed in a pan-genomic analysis by using 41 genomes, revealing that two strains (LA1063 and BCRC 17481) exhibited absences of the redox-sensing transcriptional repressor Rex 2 (Rex2) gene, whereas the other 39 strains had this gene (Figure 4). However, when we analyzed the specific primer pair targeted by Rex2, we found that strains LA1063 and BCRC 17481 had a 68-bp deletion in this gene (Supplementary Materials Figure S2a,b).

Figure 4.

Development of the LA1063 strain-specific PCR-based identification method. Heatmap and neighbor-joining tree of the analyzed the 41 Lactobacillus acidophilus strains based on the presence or absence of genes. Arrows indicate strain-specific markers for Lactobacillus acidophilus LA1063 and BCRC 17481 strains.

To date, no consensus has been reached on the definition of a strain based on the number of nucleotide differences. However, a single-base pair cutoff has been discussed and considered by expert panels [57]. The 21 loci from the cgMLST data of 1390 core genes could be used to discriminate LA1063 from the other 40 strains (Table 5); therefore, to distinguish between LA1063 and other L. acidophilus strains, four of the 21 discriminated loci from the cgMLST data were selected, and they were confirmed to have T→G, T→G, T→G, and A→C nucleotide variations at the phoU, secY, tilS, and uvrA_1 loci, respectively (Supplementary Figure S3).

Table 5.

Strain-specific loci for Lactobacillus acidophilus LA1063.

Sharma et al. [70] successfully used RAPD, a repetitive element–based PCR method, and MLST for tracking intentionally inoculated LAB strains in yogurt and probiotic powder; their proposed polyphasic approach effectively tracked the starter strains. However, such an approach is time- and cost-intensive. By contrast, multiplex minisequencing can be used to identify the nucleotide located at a given site. This method is especially useful for simultaneously screening many SNPs within one reaction tube. Automated fluorescent capillary electrophoresis for minisequencing products can be performed in only 40 min, which is less than the 2.5 h required for direct sequencing. Multiplex minisequencing has been successfully developed for the identification and differentiation of probiotic bacteria at the strain, subspecies, and species levels [46,71,72,73].

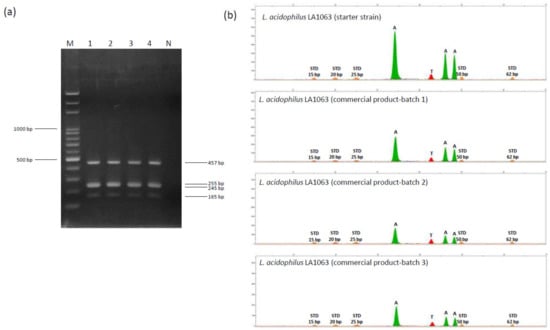

Subsequently, multiplex minisequencing was performed to directly identify strain-specific SNP-based markers in the probiotic LA1063 strain. Primers specific to SNPs were used to achieve simultaneous annealing next to the nucleotide at strain-specific SNPs, and three of the primers included different-length 5′ nonhomologous poly(dGACT) tails to facilitate terminator-incorporated primer differentiation by size (Table 2). Subsequently, multiple PCR amplicons with four diagnostic sizes (165, 245, 255, and 457 bp) (Figure 5a) were purified and applied in multiplex minisequencing. Four peaks with expected colors and positions were observed for LA1063 (Figure 5b). Next, by using the strain-specific multiplex PCR and SNP primers, separate batches of LA1063-derived probiotics in powder products were analyzed, and the nucleotide bases were found to be identical to those of the original probiotic strain (Figure 5), which demonstrated the specificity and reproducibility of this method.

Figure 5.

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping of four polymorphisms in the phoU, secY, tilS, and uvrA_1 distinguished genes on the Lactobacillus acidophilus LA1063 strain. (a) Electropherogram of a 2% agarose gel containing multiple PCR products derived from four DNA fragments. Lane M, 100-bp ladder DNA marker; lane 1, LA1063 probiotic strain; lanes 2‒4, LA1063 isolated from separate batches of its derived probiotic product; and lane N, negative control. (b) Electropherograms obtained from the LA1063 strains by four-plex SNaPshot minisequencing assay. The X-axis represents the size of the minisequencing products (nucleotides); the Y-axis represents relative fluorescence units (RFUs). STD: GS120 LIZ size standard.

4. Conclusions

Conventionally, the strain-level typing and identification of monophyletic species such as L. acidophilus is challenging. Our study revealed that comparative genomic analysis could substantially increase discriminatory power to reach high-resolution typing on the basis of the allele profiles of the cgMLST scheme, and the 41 L. acidophilus strains were categorized into 34 STs. Consequently, the strain-specific identification method relying on INDEL-SNP markers was successfully developed and made available for the direct discrimination and tracking of probiotic strains in commercial products.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/8/9/1445/s1, Figure S1: Unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) dendrogram based on OrthoANI values among the 41 Lactobacillus acidophilus strains. Figure S2: Alignment of Rex2 gene sequences among the 11 Lactobacillus acidophilus strains reference strains and LA1063, differs in a 68-bp insertion/deletion. Figure S3: Discriminated loci between Lactobacillus acidophilus LA1063 and BCRC 17481. Table S1: Genomic characteristics of Lactobacillus acidophilus strains. Table S2. Genes and primers used for validation of reference strains. Table S3. List of the 1390 cgMLST loci in 41 Lactobacillus acidophilus strains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-H.H. and K.W.; formal analysis, C.-H.H., C.-C.C., S.-H.C., J.-S.L. (Jong-Shian Liou), and Y.-C.L.; funding acquisition, C.-H.H. and J.-S.L. (Jin-Seng Lin); methodology, C.-H.H. and C.-C.C.; project administration, C.-H.H.; supervision, L.H. and K.W.; visualization, C.-H.H. and C.-C.C.; writing—original draft, C.-H.H; and writing—review and editing, L.H. and K.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, ROC (project no. MOST 108-2320-B-080-001) and Ministry of Economic Affairs, Taiwan, ROC (project no. 109-EC-17-A-22-0525).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Chii-Cherng Liao and Wen-Shen Chu (Food Industry Research and Development Institute, Hsinchu, Taiwan) for their encouragement during the course of this research activity.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fujisawa, T.; Benno, Y.; Yaeshima, T.; Mitsuoka, T. Taxonomic study of the Lactobacillus acidophilus group, with recognition of Lactobacillus gallinarum sp. nov. and Lactobacillus johnsonii sp. nov. and synonymy of Lactobacillus acidophilus group A3 (Johnson et al. 1980) with the type strain of Lactobacillus amylovorus (Nakamura 1981). Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1992, 42, 487–491. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliland, S.E.; Speck, M.L.; Morgan, C.G. Detection of Lactobacillus acidophilus in feces of humans, pigs, and chickens. Appl. Microbiol. 1975, 30, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Pena, M.D.; Castro-Escarpulli, G.; Aguilera-Arreola, M.G. Lactobacillus species isolated from vaginal secretions of healthy and bacterial vaginosis-intermediate Mexican women: A prospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Méndez, C.; Badet, C.; Yáñez, A.; Dominguez, M.A.; Giono, S.; Richard, B.; Nancy, J.; Dorignac, G. Identification of oral strains of Lactobacillus species isolated from Mexican and French children. J. Dent. Oral Hyg. 2009, 1, 009–016. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, M.; Plummer, S.; Marchesi, J.; Mahenthiralingam, E. The life history of Lactobacillus acidophilus as a probiotic: A tale of revisionary taxonomy, misidentification and commercial success. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2013, 349, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, M.E.; Klaenhammer, T.R. The scientific basis of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM functionality as a probiotic. J. Dairy Sci. 2001, 84, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, L.; Capurso, L. FAO/WHO guidelines on probiotics: 10 years later. J. Clin. Gastroentero. 2012, 46, S1–S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewale, R.N.; Sawale, P.D.; Khedkar, C.D.; Singh, A. Selection criteria for probiotics: A review. Int. J. Probiotics Prebiotics 2014, 9, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Huys, G.; Vancanneyt, M.; D’Haene, K.; Vankerckhoven, V.; Goossens, H.; Swings, J. Accuracy of species identity of commercial bacterial cultures intended for probiotic or nutritional use. Res. Microbiol. 2006, 157, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, M.J.; Jolley, K.A.; Bray, J.E.; Aerts, M.; Vandamme, P.; Maiden, M.C.J.; Marchesi, J.R.; Mahenthiralingam, E. The domestication of the probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus acidophilus. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, P.D.; Lacher, W.; Pfeiler, E.A.; Elkins, C.A. Development of a tiered multilocus sequence typing scheme for members of the Lactobacillus acidophilus complex. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 7220–7228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šedo, O.; Vávrová, A.; Vad’urová, M.; Tvrzová, L.; Zdráhal, Z. The influence of growth conditions on strain differentiation within the Lactobacillus acidophilus group using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry profiling. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2013, 27, 2729–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaminathan, B.; Barrett, T.J.; Hunter, S.B.; Tauxe, R.V. PulseNet: The molecular subtyping network for foodborne bacterial disease surveillance, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2001, 7, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaillou, S.; Lucquin, I.; Najjari, A.; Zagorec, M.; Cham-pomier-Verges, M.C. Population genetics of Lactobacillus sakei reveals three lineages with distinct evolutionary histories. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, T.; Liu, W.; Song, Y.; Xu, H.; Menghe, B.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Z. The evolution and population structure of Lactobacillus fermentum from different naturally fermented products as determined by multilocus sequence typing (MLST). BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parolo, C.C.; Do, T.; Henssqe, U.; Alves, L.S.; de Santan Giongo, F.E.; Corcao, G.; Maltz, M.; Beighton, D. Genetic diversity of Lactobacillus paracasei isolated from in situ human oral biofilms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 111, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanigawa, K.; Watanabe, K. Multilocus sequence typing reveals a novel subspeciation of Lactobacillus delbrueckii. Microbiology 2011, 157, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, W.; Yu, J.; Song, Y.; Menhe, B.; Zhang, H.; Sun, X. Use of multilocus sequence typing to infer genetic diversity and population structure of Lactobacillus plantarum isolates from different sources. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxman, B.; Zhang, L.; Koopman, J.S.; Manning, S.D.; Marrs, C.F. Choosing an appropriate bacterial typing technique for epidemiologic studies. Epidemiol. Perspect. Innov. 2005, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, S.N.; Vora, G.J.; Walper, S.A. Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus acidophilus strain ATCC 53544. Genome Announc. 2017, 5, e01138-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iartchouk, O.; Kozyavkin, S.; Karamychev, V.; Slesarev, A. Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus acidophilus FSI4, isolated from yogurt. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e00166-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomino, M.M.; Allievi, M.C.; Martin, J.F.; Waehner, P.M.; Acosta, M.P.; Rivas, C.S.; Ruzal, S.M. Draft genome sequence of the probiotic strain Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356. Genome Announc. 2015, 5, e01421-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, B.; Barrangou, R. Complete genome sequence of probiotic strain Lactobacillus acidophilus La-14. Genome Announc. 2013, 1, e00376-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouioui, I.; Carro, L.; García-López, M.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.; Woyke, T.; Kyrpides, N.; Klenk, H.P.; Goodfellow, M.; Göker, M. Genome-based taxonomic classification of the phylum Actinobacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Harri, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.; Oren, A.; Ventosa, A.; Christensen, H.; Arahal, D.R.; da Costa, M.S.; Rooney, A.P.; Yi, H.; Xu, X.W.; De Meyer, S.; et al. Proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schürch, A.C.; Arredondo-Alonso, S.; Willems, R.J.L.; Goering, R.V. Whole genome sequencing options for bacterial strain typing and epidemiologic analysis based on single nucleotide polymorphism versus gene-by-gene-based approaches. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uelze, L.; Grützke, J.; Borowiak, M.; Hammerl, J.A.; Juraschek, K.; Deneke, C.; Tausch, S.H.; Malorny, B. Typing methods based on whole genome sequencing data. One Health Outlook 2020, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, B.; Prior, K.; Bender, J.K.; Harmsen, D.; Klare, I.; Fuchs, S.; Bethe, A.; Zühlke, D.; Göhler, A.; Schwarz, S.; et al. A core genome multilocus sequence typing scheme for Enterococcus faecalis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 57, e01686-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, M.E.; Alikhan, N.F.; Dallman, T.J.; Zhou, Z.; Grant, K.; Maiden, M.C.J. Comparative analysis of core genome MLST and SNP typing within a European Salmonella serovar Enteritidis outbreak. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 274, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.J.; Lappi, V.; Wolfgang, W.J.; Lapierre, P.; Palumbo, M.J.; Medus, C.; Boxrud, D. Characterization of foodborne outbreaks of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis with whole-genome sequencing single nucleotide polymorphism-based analysis for surveillance and outbreak detection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 3334–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, Y.; Kristiansen, K.; Wang, J. SOAP: Short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 713–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Ouk Kim, Y.; Park, S.C.; Chun, J. OrthoANI: An improved algorithm and software for calculating average nucleotide identity. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1100–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Lin, J.W.; Chen, C.C. cano-wgMLST_BacCompare: A bacterial genome analysis platform for epidemiological investigation and comparative genomic analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, A.J.; Cummins, C.A.; Hunt, M.; Wong, V.K.; Reuter, S.; Holden, M.T.; Fookes, M.; Falush, D.; Keane, J.A.; Parkhill, J. Roary: Rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3691–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.F.; Foulds, L.R. Comparison of phylogenetic trees. Math. Biosci. 1981, 53, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A. FigTree. Available online: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ (accessed on 6 January 2016).

- Zhou, Z.; Alikhan, N.F.; Sergeant, M.J.; Luhmann, N.; Vaz, C.; Francisco, A.P.; Carrico, J.A.; Achtman, M. GrapeTree: Visualization of core genomic relationships among 100,000 bacterial pathogens. Genome Res. 2018, 28, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Cepas, J.; Serra, F.; Bork, P. ETE 3: Reconstruction, analysis, and visualization of phylogenomic data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1635–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, P.; Ernst, D.; Wehenkel, L. Extremely randomized trees. Mach. Learn. 2006, 63, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.D.; Gibson, T.J.; Plewniak, F.; Jeanmougin, F.; Higgins, D.G. The CLUSTAL X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 4876–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Librado, P.; Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Chang, M.T.; Huang, M.C.; Lee, F.L. Application of the SNaPshot minisequencing assay to species identification in the Lactobacillus casei group. Mol. Cell. Probes 2011, 25, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomonaco, S.; Furumoto, E.; Loquasto, J.J.R.; Morra, P.; Grassi, A.; Roberts, R.F. Development of a rapid SNP-typing assay to differentiate Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis strains used in probiotic-supplemented dairy products. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 804–812. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.H.; Huang, L. Rapid species- and subspecies-specific level classification and identification of Lactobacillus casei group members using MALDI Biotyper combined with ClinProTools. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briczinski, E.P.; Loquasto, J.R.; Barrangou, R.; Didley, E.G.; Roberts, A.M.; Roberts, R.F. Strain-specific genotyping of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis by using single-nucleotide polymorphisms, insertions, and deletions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7501–7508. [Google Scholar]

- Milani, C.; Duranti, S.; Lugli, G.A.; Bottacini, F.; Strati, F.; Arioli, S.; Foroni, E.; Turroni, F.; van Sinderen, D.; Ventura, M. Comparative genomics of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis reveals a strict monophyletic bifidobacterial taxon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 4304–4315. [Google Scholar]

- Ghattargi, V.C.; Gaikwad, M.A.; Meti, B.S.; Nimonkar, Y.S.; Dixit, K.; Prakash, O.; Shouche, Y.S.; Pawar, S.P.; Dhotre, D.P. Comparative genome analysis reveals key genetic factors associated with probiotic property in Enterococcus faecium strains. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyereisen, M.; Mahony, J.; Kelleher, P.; Roberts, R.J.; O’Sullivan, T.; Geertman, J.A.; van Sinderen, D. Comparative genome analysis of the Lactobacillus brevis species. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.; Falasconi, I.; Molinari, P.; Treu, L.; Basile, A.; Vezzi, A.; Campanaro, S.; Morelli, L. Genomic comparison of Lactobacillus helveticus strains highlights probiotic potential. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.L.; Kim, D.H. Genome-wide comparison reveals a probiotic strain Lactococcus lactis WFLU12 isolated from the gastrointestinal tract of olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) harboring genes supporting probiotic action. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Ji, H. Complete genome sequencing and comparative genome characterization of Lactobacillus johnsonii ZLJ010, a potential probiotic with health-promoting properties. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treven, P. 2015. Strategies to develop strain-specific PCR based assays for probiotics. Benef. Microbes 2015, 6, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.A.; Schoeni, J.L.; Vegge, C.; Pane, M.; Stahl, B.; Bradley, M.; Goldman, V.S.; Burguière, P.; Atwater, J.B.; Sanders, M.E. Improving end-user trust in the quality of commercial probiotic products. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brigidi, P.; Vitali, B.; Swennen, E.; Altomare, L.; Rossi, M.; Matteuzzi, D. Specific detection of Bifidobacterium strains in a pharmaceutical probiotic product and in human feces by polymerase chain reaction. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 23, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, K.; Alatossava, T. Specific identification of certain probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains with PCR primers based on phage-related sequences. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 84, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapetsas, A.; Vavoulidis, E.; Galanis, A.; Sandaltzopoulos, R.; Kourkoutas, Y. Rapid detection and identification of probiotic Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393 by multiplex PCR. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 18, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlroos, T.; Tynkkynen, S. Quantitative strain-specific detection of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in human faecal samples by real-time PCR. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 106, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, J.; Matsuki, T.; Sasamoto, M.; Tomii, Y.; Watanabe, K. Identification and quantification of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota in human feces with strain-specific primers derived from randomly amplified polymorphic DNA. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 126, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, J.; Tanigawa, K.; Kudo, Y.; Makino, H.; Watanabe, K. Identification and quantification of viable Bifidobacterium breve strain Yakult in human faeces by using strain-specific primers and propidium monoazide. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 110, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, J.; Watanabe, K. Quantitative detection of viable Bifidobacterium bifidum BF-1 cells in human feces by using propidium monoazide and strain-specific primers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 2182–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.H.; Shih, T.W.; Pan, T.M. A “Ct contrast”-based strain-specific real-time quantitative PCR system for Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2018, 51, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzotto, M.; Maffeis, C.; Paternoster, T.; Ferrario, R.; Rizzotti, L.; Pellegrino, M.; Dellaglio, F.; Torriani, S. Lactobacillus paracasei A survives gastrointestinal passage and affects the fecal microbiota of healthy infants. Res. Microbiol. 2006, 157, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisto, A.; De Bellis, P.; Visconti, A.; Morelli, L.; Lavermicocca, P. Development of a PCR assay for the strain-specific identification of probiotic strain Lactobacillus paracasei IMPC2.1. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 136, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshimitsu, T.; Nakamura, M.; Ikegami, S.; Terahara, M.; Itou, H. Strain-specific identification of Bifidobacterium bifidum OLB6378 by PCR. Biosci. Biotech. Bioch. 2013, 77, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.J.Z.; Morovic, W.; Demeules, M.; Stahl, B.; Sindelar, C.W. Absolute enumeration of probiotic strains Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM®® and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Bl-04®® via chip-based digital PCR. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 704. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Kaur, J.; Lee, S.; Park, Y.C. Tracking of intentionally inoculated lactic acid bacteria strains in yogurt and probiotic powder. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Chang, M.T.; Huang, M.C.; Lee, F.L. Rapid identification of Lactobacillus plantarum group using the SNaPshot minisequencing assay. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 34, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Chang, M.T.; Huang, M.C.; Wang, L.T.; Huang, L.; Lee, F.L. Discrimination of the Lactobacillus acidophilus group using sequencing, species-specific PCR and SNaPshot mini-sequencing technology based on the recA gene. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 2703–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.H.; Huang, L.; Chang, M.T.; Wu, C.P. Use of novel specific primers targeted to pheS and tuf gene for species and subspecies identification and differentiation of the Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Bacillus licheniformis. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 11, 264–270. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).