Impact of Surfactant Protein-A Variants on Survival in Aged Mice in Response to Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection and Ozone: Serendipity in Action

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Preparation of Bacteria

2.3. Infection of Mice with K. Pneumoniae

2.4. Filtered Air (FA) and Ozone (O3) Exposure and Infection

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

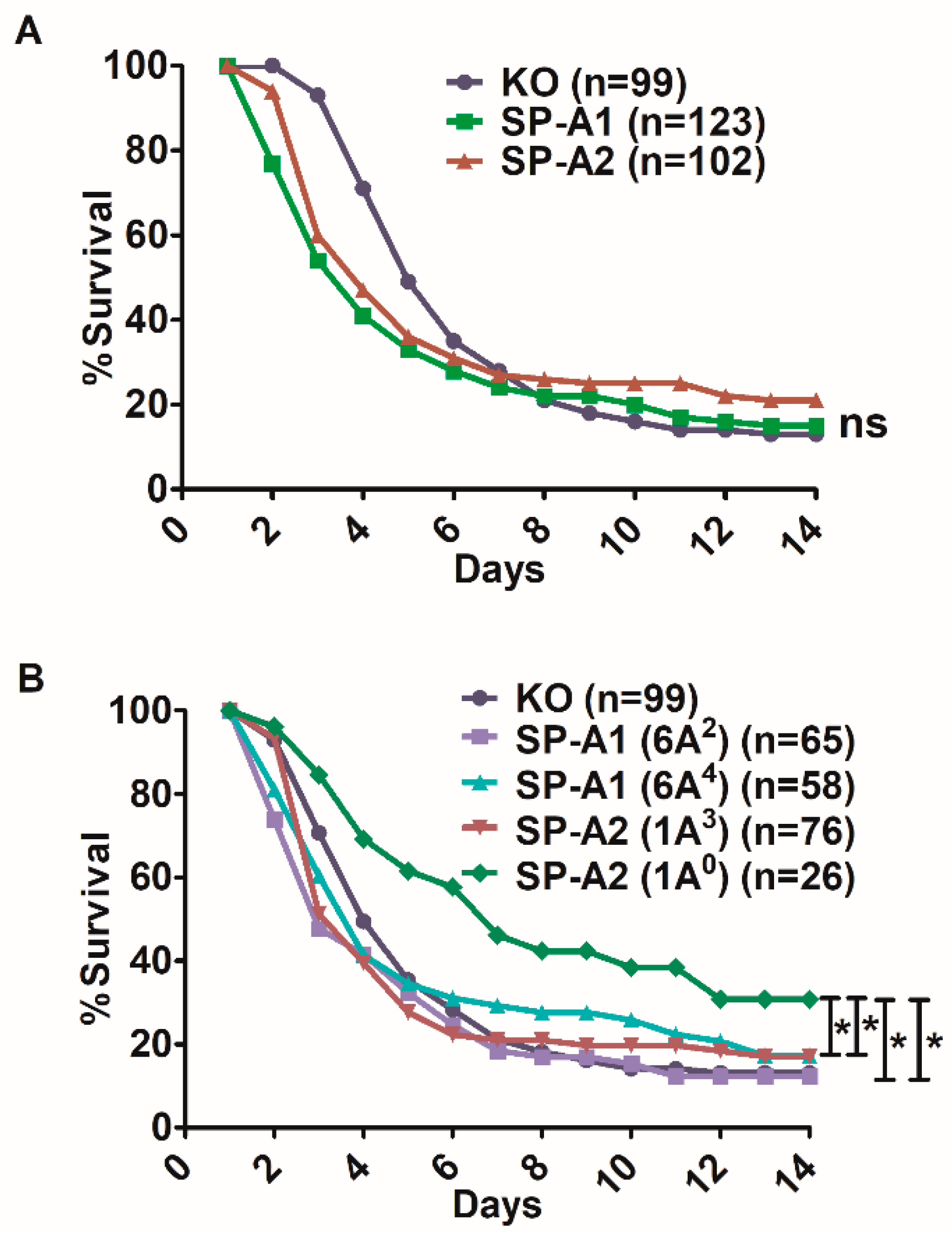

3.1. Effect of SP-A Variants on Survival after Infection

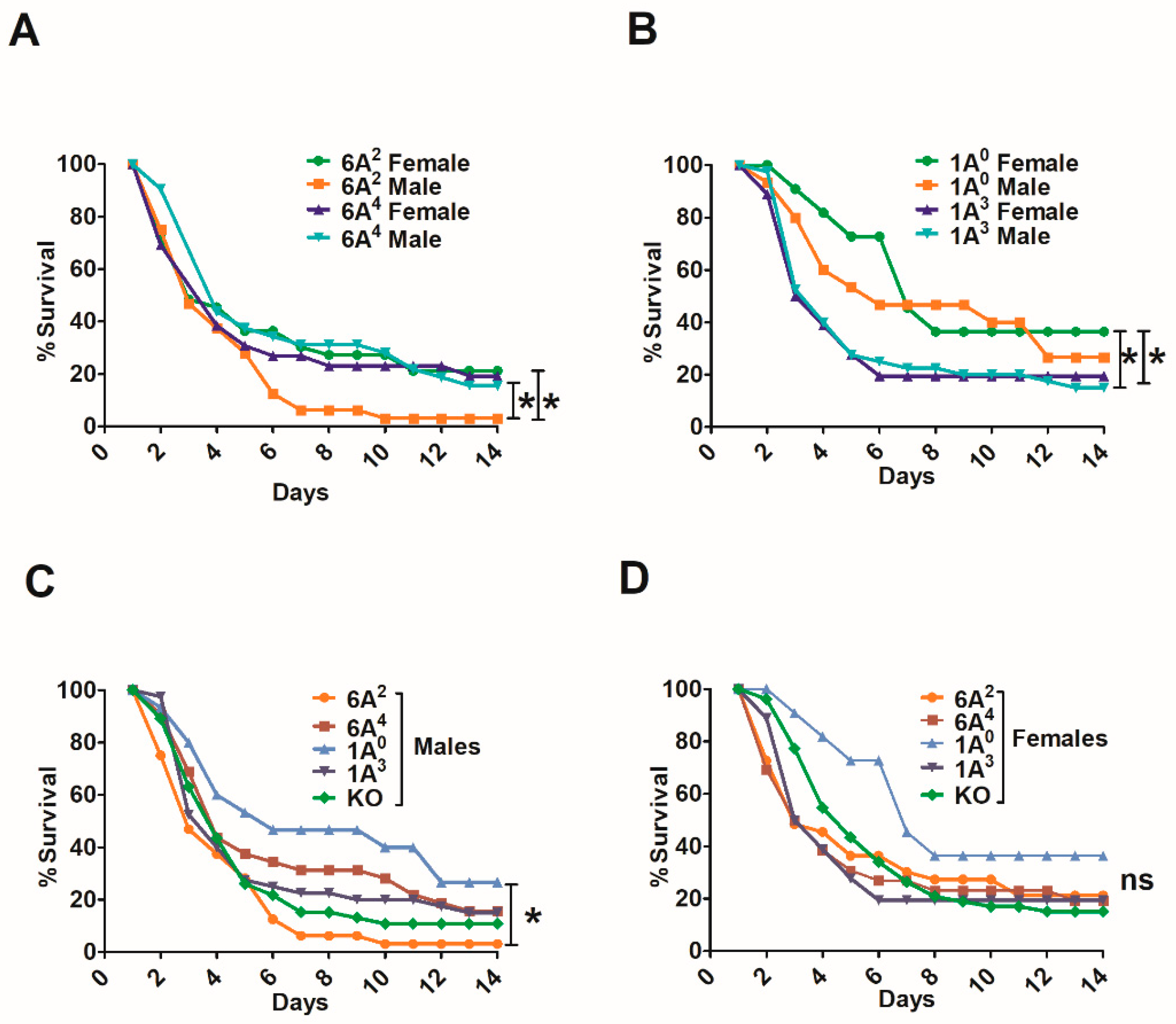

3.2. Sex Differences in Survival of SP-A1, SP-A2, and KO Mice

3.2.1. Differences between Gene-Specific Variants

3.2.2. Differences among SP-A1 and SP-A2 Variants

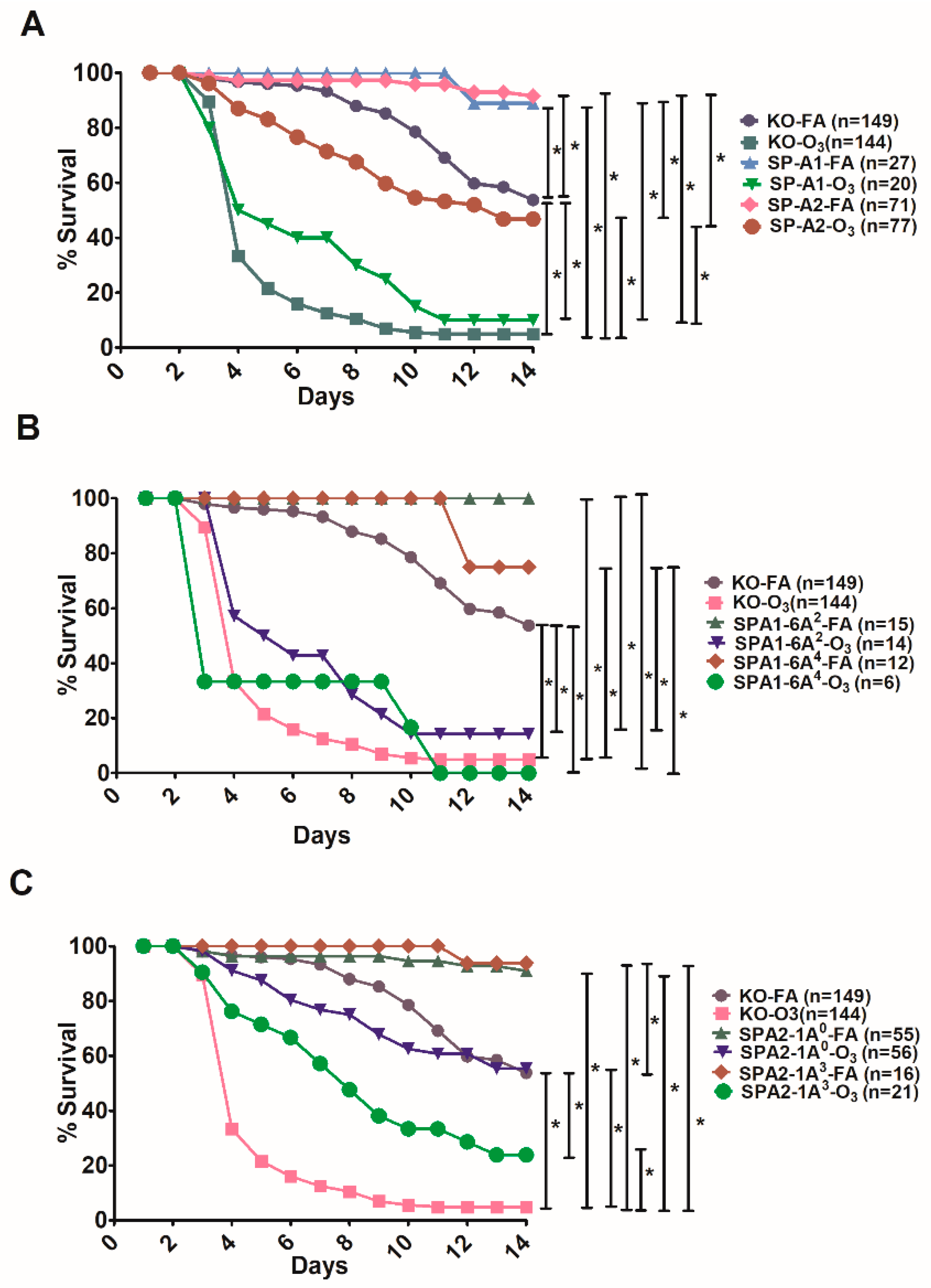

3.3. Effect of SP-A Variants on Survival in Response to O3 or FA Exposure Prior to Infection

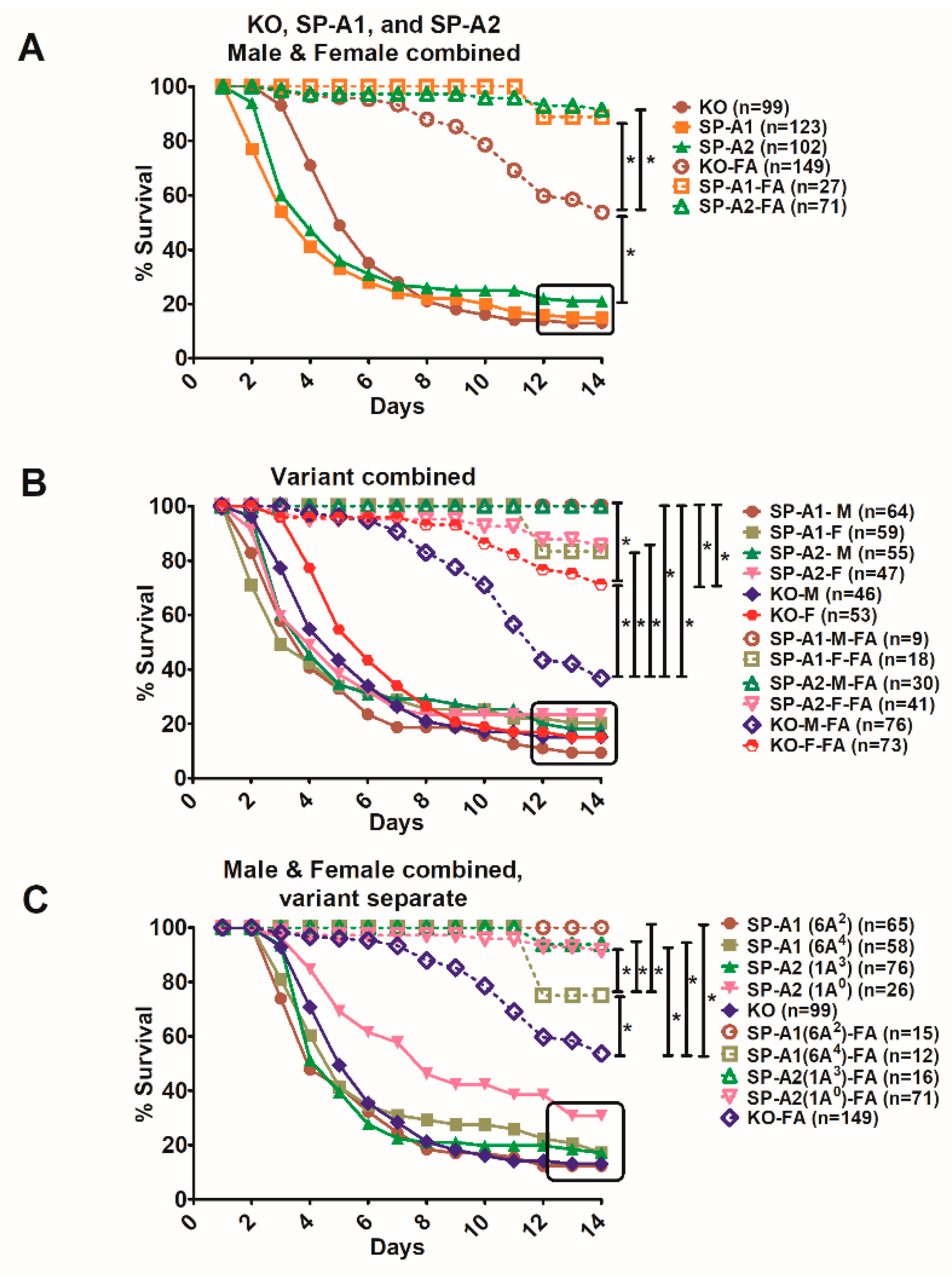

3.4. Differences in Survival as A Function of Variant in Male and Female SP-A2 and KO-Infected Mice with Prior FA or O3 Exposure

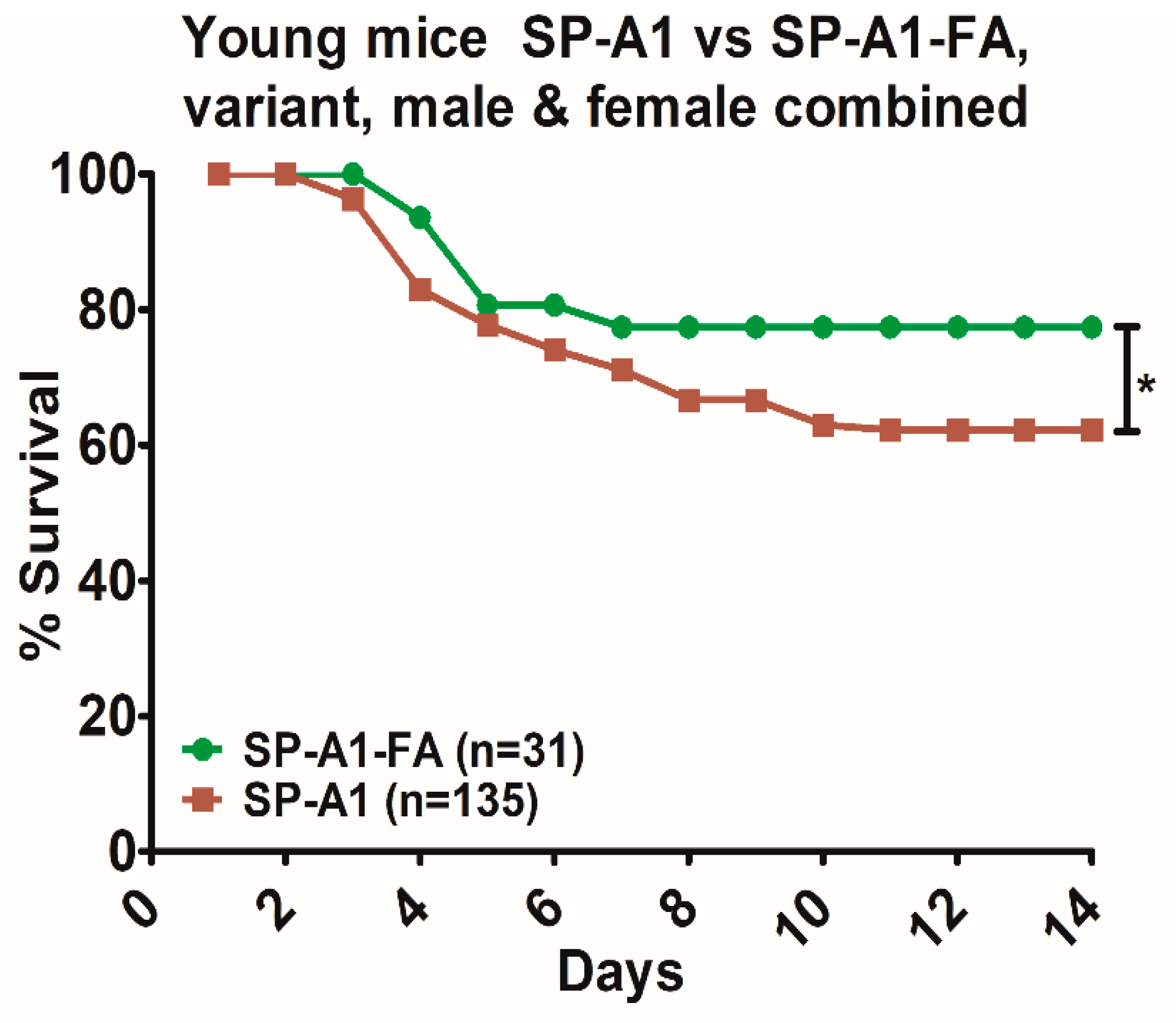

3.5. Comparison of Survival between Animals with Infection Alone and Animals with FA Exposure Prior to Infection

4. Discussion

4.1. Young vs Aged

4.2. In Response to Infection Alone

4.3. In Response to O3 or FA and Infection

4.4. In Response to Infection with Prior Filtered Air Exposure

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedlander, C. Ueber die Schizomyceten bei der acuten fibrosen Penumonie. Arch. F. Pathol. Anat. 1882, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofteridis, D.P.; Papadakis, J.A.; Bouros, D.; Nikolaides, P.; Kioumis, G.; Levidiotou, S.; Maltezos, E.; Kastanakis, S.; Kartali, S.; Gikas, A. Nosocomial lower respiratory tract infections: Prevalence and risk factors in 14 Greek hospitals. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 23, 888–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podschun, R.; Ullmann, U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: Epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 11, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagley, S.T. Habitat association of Klebsiella species. Infect. Control Ic 1985, 6, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, C.; Thom, K.A.; Masnick, M.; Johnson, J.K.; Harris, A.D.; Morgan, D.J. Frequency of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing and non-KPC-producing Klebsiella species contamination of healthcare workers and the environment. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2014, 35, 426–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.T.; Liebenthal, D.; Tran, T.K.; Ngoc Thi Vu, B.; Ngoc Thi Nguyen, D.; Thi Tran, H.K.; Thi Nguyen, C.K.; Thi Vu, H.L.; Fox, A.; Horby, P.; et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae oropharyngeal carriage in rural and urban Vietnam and the effect of alcohol consumption. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paczosa, M.K.; Mecsas, J. Klebsiella pneumoniae: Going on the Offense with a Strong Defense. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, 629–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill, S.S.; Edwards, J.R.; Bamberg, W.; Beldavs, Z.G.; Dumyati, G.; Kainer, M.A.; Lynfield, R.; Maloney, M.; McAllister-Hollod, L.; Nadle, J.; et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.C.; Paterson, D.L.; Sagnimeni, A.J.; Hansen, D.S.; Von Gottberg, A.; Mohapatra, S.; Casellas, J.M.; Goossens, H.; Mulazimoglu, L.; Trenholme, G.; et al. Community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: Global differences in clinical patterns. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmskov, U.; Thiel, S.; Jensenius, J.C. Collections and ficolins: Humoral lectins of the innate immune defense. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 21, 547–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, U.; Greenhough, T.J.; Waters, P.; Shrive, A.K.; Ghai, R.; Kamran, M.F.; Bernal, A.L.; Reid, K.B.; Madan, T.; Chakraborty, T. Surfactant proteins SP-A and SP-D: Structure, function and receptors. Mol. Immunol. 2006, 43, 1293–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.R. Pulmonary surfactant: A front line of lung host defense. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1453–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelps, D.S. Surfactant regulation of host defense function in the lung: A question of balance. Pediatric Pathol. Mol. Med. 2001, 20, 269–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, E.; Hartshorn, K.; Ofek, I. Collectins and pulmonary innate immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2000, 173, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, E.; Wright, J.R. Surfactant proteins a and d and pulmonary host defense. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2001, 63, 521–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, E.C. Collectins and pulmonary host defense. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1998, 19, 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.R.; Youmans, D.C. Pulmonary surfactant protein A stimulates chemotaxis of alveolar macrophage. Am. J. Physiol. 1993, 264, L338–L344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariencheck, W.I.; Savov, J.; Dong, Q.; Tino, M.J.; Wright, J.R. Surfactant protein A enhances alveolar macrophage phagocytosis of a live, mucoid strain of P. aeruginosa. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 277, L777–L786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubchandani, K.R.; Snyder, J.M. Surfactant protein A (SP-A): The alveolus and beyond. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2001, 15, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremlev, S.G.; Umstead, T.M.; Phelps, D.S. Effects of surfactant protein A and surfactant lipids on lymphocyte proliferation in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. 1994, 267, L357–L364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borron, P.; McCormack, F.X.; Elhalwagi, B.M.; Chroneos, Z.C.; Lewis, J.F.; Zhu, S.; Wright, J.R.; Shepherd, V.L.; Possmayer, F.; Inchley, K.; et al. Surfactant protein A inhibits T cell proliferation via its collagen-like tail and a 210-kDa receptor. Am. J. Physiol. 1998, 275, L679–L686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, K.G.; Garner, H.; Wright, J.R. Surfactant protein A modulates the differentiation of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2003, 284, L232–L241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, R.; Umstead, T.M.; Ponnuru, P.; Guo, X.; Hawgood, S.; Phelps, D.S.; Floros, J. Role of surfactant protein-A (SP-A) in lung injury in response to acute ozone exposure of SP-A deficient mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2007, 220, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikerov, A.N.; Haque, R.; Gan, X.; Guo, X.; Phelps, D.S.; Floros, J. Ablation of SP-A has a negative impact on the susceptibility of mice to Klebsiella pneumoniae infection after ozone exposure: Sex differences. Respir. Res. 2008, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeVine, A.M.; Bruno, M.D.; Huelsman, K.M.; Ross, G.F.; Whitsett, J.A.; Korfhagen, T.R. Surfactant protein A-deficient mice are susceptible to group B streptococcal infection. J. Immunol. 1997, 158, 4336–4340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- LeVine, A.M.; Kurak, K.E.; Bruno, M.D.; Stark, J.M.; Whitsett, J.A.; Korfhagen, T.R. Surfactant protein-A-deficient mice are susceptible to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1998, 19, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madan, T.; Reid, K.B.; Clark, H.; Singh, M.; Nayak, A.; Sarma, P.U.; Hawgood, S.; Kishore, U. Susceptibility of mice genetically deficient in SP-A or SP-D gene to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Mol. Immunol. 2010, 47, 1923–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiAngelo, S.; Lin, Z.; Wang, G.; Phillips, S.; Ramet, M.; Luo, J.; Floros, J. Novel, non-radioactive, simple and multiplex PCR-cRFLP methods for genotyping human SP-A and SP-D marker alleles. Dis. Markers 1999, 15, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karinch, A.M.; Floros, J. 5′ splicing and allelic variants of the human pulmonary surfactant protein A genes. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1995, 12, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floros, J.; DiAngelo, S.; Koptides, M.; Karinch, A.M.; Rogan, P.K.; Nielsen, H.; Spragg, R.G.; Watterberg, K.; Deiter, G. Human SP-A locus: Allele frequencies and linkage disequilibrium between the two surfactant protein A genes. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1996, 15, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floros, J.; Hoover, R.R. Genetics of the hydrophilic surfactant proteins A and D. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1998, 1408, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Verdugo, I.; Wang, G.; Floros, J.; Casals, C. Structural analysis and lipid-binding properties of recombinant human surfactant protein a derived from one or both genes. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 14041–14053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Wang, G.; Phelps, D.S.; Al-Mondhiry, H.; Floros, J. Human SP-A genetic variants and bleomycin-induced cytokine production by THP-1 cells: Effect of ozone-induced SP-A oxidation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2004, 286, L546–L553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikerov, A.N.; Umstead, T.M.; Huang, W.; Liu, W.; Phelps, D.S.; Floros, J. SP-A1 and SP-A2 variants differentially enhance association of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with rat alveolar macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2005, 288, L150–L158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mikerov, A.N.; Wang, G.; Umstead, T.M.; Zacharatos, M.; Thomas, N.J.; Phelps, D.S.; Floros, J. Surfactant protein A2 (SP-A2) variants expressed in CHO cells stimulate phagocytosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa more than do SP-A1 variants. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 1403–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Noutsios, G.T.; Thorenoor, N.; Zhang, X.; Phelps, D.S.; Umstead, T.M.; Durrani, F.; Floros, J. SP-A2 contributes to miRNA-mediated sex differences in response to oxidative stress: Pro-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and anti-oxidant pathways are involved. Biol. Sex Differ. 2017, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberley, R.E.; Snyder, J.M. Recombinant human SP-A1 and SP-A2 proteins have different carbohydrate-binding characteristics. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2003, 284, L871–L881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, M.; Lin, H.M.; Montano, M.; Jenkins, A.L.; Estrada, A.; Lin, Z.; Wang, G.; DiAngelo, S.L.; Guo, X.; Umstead, T.M.; et al. Surfactant protein A and B genetic variants predispose to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Hum. Genet. 2003, 113, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorenoor, N.; Umstead, T.M.; Zhang, X.; Phelps, D.S.; Floros, J. Survival of Surfactant Protein-A1 and SP-A2 Transgenic Mice After Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection, Exhibits Sex-, Gene-, and Variant Specific Differences; Treatment With Surfactant Protein Improves Survival. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorenoor, N.; Zhang, X.; Umstead, T.M.; Scott Halstead, E.; Phelps, D.S.; Floros, J. Differential effects of innate immune variants of surfactant protein-A1 (SFTPA1) and SP-A2 (SFTPA2) in airway function after Klebsiella pneumoniae infection and sex differences. Respir. Res. 2018, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Bates-Kenney, S.R.; Tao, J.Q.; Phelps, D.S.; Floros, J. Differences in biochemical properties and in biological function between human SP-A1 and SP-A2 variants, and the impact of ozone-induced oxidation. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 4227–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Myers, C.; Mikerov, A.; Floros, J. Effect of cysteine 85 on biochemical properties and biological function of human surfactant protein A variants. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 8425–8435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Phelps, D.S.; Umstead, T.M.; Floros, J. Human SP-A protein variants derived from one or both genes stimulate TNF-alpha production in the THP-1 cell line. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2000, 278, L946–L954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Taneva, S.; Keough, K.M.; Floros, J. Differential effects of human SP-A1 and SP-A2 variants on phospholipid monolayers containing surfactant protein B. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1768, 2060–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wang, G.; Umstead, T.M.; Phelps, D.S.; Al-Mondhiry, H.; Floros, J. The effect of ozone exposure on the ability of human surfactant protein a variants to stimulate cytokine production. Env. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karinch, A.M.; Deiter, G.; Ballard, P.L.; Floros, J. Regulation of expression of human SP-A1 and SP-A2 genes in fetal lung explant culture. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta 1998, 1398, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Snyder, J. Differential regulation of SP-A1 and SP-A2 genes by cAMP, glucocorticoids, and insulin. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 1998, 274, L177–L185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavo, L.M.; Ertsey, R.; Gao, B.Q. Human surfactant proteins A1 and A2 are differentially regulated during development and by soluble factors. Am. J. Physiol. 1998, 275, L653–L669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveyra, P.; DiAngelo, S.L.; Floros, J. An 11-nt sequence polymorphism at the 3′UTR of human SFTPA1 and SFTPA2 gene variants differentially affect gene expression levels and miRNA regulation in cell culture. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2014, 307, L106–L119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveyra, P.; Raval, M.; Simmons, B.; Diangelo, S.; Wang, G.; Floros, J. The untranslated exon B of human surfactant protein A2 mRNAs is an enhancer for transcription and translation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2011, 301, L795–L803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tagaram, H.R.; Wang, G.; Umstead, T.M.; Mikerov, A.N.; Thomas, N.J.; Graff, G.R.; Hess, J.C.; Thomassen, M.J.; Kavuru, M.S.; Phelps, D.S.; et al. Characterization of a human surfactant protein A1 (SP-A1) gene-specific antibody; SP-A1 content variation among individuals of varying age and pulmonary health. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2007, 292, L1052–L1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Guo, X.; Floros, J. Human SP-A 3′-UTR variants mediate differential gene expression in basal levels and in response to dexamethasone. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2003, 284, L738–L748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsotakos, N.; Silveyra, P.; Lin, Z.; Thomas, N.; Vaid, M.; Floros, J. Regulation of translation by upstream translation initiation codons of surfactant protein A1 splice variants. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2015, 308, L58–L75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noutsios, G.T.; Silveyra, P.; Bhatti, F.; Floros, J. Exon B of human surfactant protein A2 mRNA, alone or within its surrounding sequences, interacts with 14-3-3; role of cis-elements and secondary structure. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2013, 304, L722–L735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Guo, X.; Floros, J. Differences in the translation efficiency and mRNA stability mediated by 5′-UTR splice variants of human SP-A1 and SP-A2 genes. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2005, 289, L497–L508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Guo, X.; Silveyra, P.; Kimball, S.R.; Floros, J. Cap-independent translation of human SP-A 5′-UTR variants: A double-loop structure and cis-element contribution. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2009, 296, L635–L647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, D.S.; Umstead, T.M.; Floros, J. Sex differences in the acute in vivo effects of different human SP-A variants on the mouse alveolar macrophage proteome. J. Proteom. 2014, 108, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, D.S.; Umstead, T.M.; Silveyra, P.; Hu, S.; Wang, G.; Floros, J. Differences in the alveolar macrophage proteome in transgenic mice expressing human SP-A1 and SP-A2. J. Proteom. Genom. Res. 2013, 1, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsotakos, N.; Phelps, D.S.; Yengo, C.M.; Chinchilli, V.M.; Floros, J. Single-cell analysis reveals differential regulation of the alveolar macrophage actin cytoskeleton by surfactant proteins A1 and A2: Implications of sex and aging. Biol. Sex Differ. 2016, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorenoor, N.; Kawasawa, Y.I.; Gandhi, C.K.; Floros, J. Sex-Specific Regulation of Gene Expression Networks by Surfactant Protein A (SP-A) Variants in Alveolar Macrophages in Response to Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Rodriguez, E.; Pascual, A.; Arroyo, R.; Floros, J.; Perez-Gil, J. Human Pulmonary Surfactant Protein SP-A1 Provides Maximal Efficiency of Lung Interfacial Films. Biophys. J. 2016, 111, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, C.R.; Nomellini, V.; Faunce, D.E.; Kovacs, E.J. Innate immunity and aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2008, 43, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajishengallis, G. Too old to fight? Aging and its toll on innate immunity. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2010, 25, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsini, E.; Battaini, F.; Lucchi, L.; Marinovich, M.; Racchi, M.; Govoni, S.; Galli, C.L. A defective protein kinase C anchoring system underlying age-associated impairment in TNF-alpha production in rat macrophages. J. Immunol. 1999, 163, 3468–3473. [Google Scholar]

- Corsini, E.; Di Paola, R.; Viviani, B.; Genovese, T.; Mazzon, E.; Lucchi, L.; Marinovich, M.; Galli, C.L.; Cuzzocrea, S. Increased carrageenan-induced acute lung inflammation in old rats. Immunology 2005, 115, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hegelan, M.; Tighe, R.M.; Castillo, C.; Hollingsworth, J.W. Ambient ozone and pulmonary innate immunity. Immunol. Res. 2011, 49, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunekreef, B. The continuing challenge of air pollution. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 36, 704–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberg, P.A. Mechanisms of the acute effects of inhaled ozone in humans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1860, 2771–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerrett, M.; Burnett, R.T.; Pope, C.A., 3rd; Ito, K.; Thurston, G.; Krewski, D.; Shi, Y.; Calle, E.; Thun, M. Long-term ozone exposure and mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, F.J.; Fussell, J.C. Air pollution and airway disease. Clin. Exp. Allergy J. Br. Soc. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 41, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voter, K.Z.; Whitin, J.C.; Torres, A.; Morrow, P.E.; Cox, C.; Tsai, Y.; Utell, M.J.; Frampton, M.W. Ozone exposure and the production of reactive oxygen species by bronchoalveolar cells in humans. Inhal. Toxicol. 2001, 13, 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almqvist, C.; Worm, M.; Leynaert, B. Impact of gender on asthma in childhood and adolescence: A GA2LEN review. Allergy 2008, 63, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Torres, J.P.; Casanova, C.; Celli, B.R. Sex, forced expiratory volume in 1 s decline, body weight change and C-reactive protein in COPD patients. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 34, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Torres, J.P.; Cote, C.G.; Lopez, M.V.; Casanova, C.; Diaz, O.; Marin, J.M.; Pinto-Plata, V.; de Oca, M.M.; Nekach, H.; Dordelly, L.J.; et al. Sex differences in mortality in patients with COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 33, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Mourtzoukou, E.G.; Vardakas, K.Z. Sex differences in the incidence and severity of respiratory tract infections. Respir. Med. 2007, 101, 1845–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkey, A.B. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in women: Exploring gender differences. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2004, 10, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Q.; Dai, L.; Wang, Y.; Zanobetti, A.; Choirat, C.; Schwartz, J.D.; Dominici, F. Association of Short-term Exposure to Air Pollution With Mortality in Older Adults. JAMA 2017, 318, 2446–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.G.; Elsayed, N.M.; Ospital, J.J.; Hacker, A.D. Influence of age on the biochemical response of rat lung to ozone exposure. Toxicol. Ind. Health 1985, 1, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Guo, X.; Diangelo, S.; Thomas, N.J.; Floros, J. Humanized SFTPA1 and SFTPA2 transgenic mice reveal functional divergence of SP-A1 and SP-A2: Formation of tubular myelin in vivo requires both gene products. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 11998–12010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikerov, A.N.; Gan, X.; Umstead, T.M.; Miller, L.; Chinchilli, V.M.; Phelps, D.S.; Floros, J. Sex differences in the impact of ozone on survival and alveolar macrophage function of mice after Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Respir. Res. 2008, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, I.C. Bacteria-mediated acute lung inflammation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 1031, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umstead, T.M.; Phelps, D.S.; Wang, G.; Floros, J.; Tarkington, B.K. In vitro exposure of proteins to ozone. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2002, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floros, J.; Wang, G.; Mikerov, A.N. Genetic complexity of the human innate host defense molecules, surfactant protein A1 (SP-A1) and SP-A2--impact on function. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2009, 19, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikerov, A.N.; Umstead, T.M.; Gan, X.; Huang, W.; Guo, X.; Wang, G.; Phelps, D.S.; Floros, J. Impact of ozone exposure on the phagocytic activity of human surfactant protein A (SP-A) and SP-A variants. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2008, 294, L121–L130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, P.G.; Strickland, D.H.; Wikström, M.E.; Jahnsen, F.L. Regulation of immunological homeostasis in the respiratory tract. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Summer, W.R.; Bagby, G.J.; Nelson, S. Innate immunity and pulmonary host defense. Immunol. Rev. 2000, 173, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strieter, R.M.; Belperio, J.A.; Keane, M.P. Host innate defenses in the lung: The role of cytokines. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 16, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabha, K.; Schmegner, J.; Keisari, Y.; Parolis, H.; Schlepper-Schaeffer, J.; Ofek, I. SP-A enhances phagocytosis of Klebsiella by interaction with capsular polysaccharides and alveolar macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. 1997, 272, L344–L352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, Y.; Betsuyaku, T.; Moriyama, C.; Nasuhara, Y.; Nishimura, M. Aging affects lipopolysaccharide-induced upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 in the lungs and alveolar macrophages. Biogerontology 2009, 10, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zissel, G.; Schlaak, M.; Müller-Quernheim, J. Age-related decrease in accessory cell function of human alveolar macrophages. J. Investig. Med. Off. Publ. Am. Fed. Clin. Res. 1999, 47, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Antonini, J.M.; Roberts, J.R.; Clarke, R.W.; Yang, H.M.; Barger, M.W.; Ma, J.Y.; Weissman, D.N. Effect of age on respiratory defense mechanisms: Pulmonary bacterial clearance in Fischer 344 rats after intratracheal instillation of Listeria monocytogenes. Chest 2001, 120, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, P.; McNish, R.W.; Peters-Golden, M.; Brock, T.G. Evaluation of phagocytosis and arachidonate metabolism by alveolar macrophages and recruited neutrophils from F344xBN rats of different ages. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2001, 122, 1899–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehmer, E.D.; Goral, J.; Faunce, D.E.; Kovacs, E.J. Age-dependent decrease in Toll-like receptor 4-mediated proinflammatory cytokine production and mitogen-activated protein kinase expression. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004, 75, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehmer, E.D.; Meehan, M.J.; Cutro, B.T.; Kovacs, E.J. Aging negatively skews macrophage TLR2- and TLR4-mediated pro-inflammatory responses without affecting the IL-2-stimulated pathway. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2005, 126, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelvarajan, R.L.; Liu, Y.; Popa, D.; Getchell, M.L.; Getchell, T.V.; Stromberg, A.J.; Bondada, S. Molecular basis of age-associated cytokine dysregulation in LPS-stimulated macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 79, 1314–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunil, V.R.; Laumbach, R.J.; Patel, K.J.; Turpin, B.J.; Lim, H.J.; Kipen, H.M.; Laskin, J.D.; Laskin, D.L. Pulmonary effects of inhaled limonene ozone reaction products in elderly rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2007, 222, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbels Bupp, M.R.; Potluri, T.; Fink, A.L.; Klein, S.L. The Confluence of Sex Hormones and Aging on Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ovidio, F.; Floros, J.; Aramini, B.; Lederer, D.; DiAngelo, S.L.; Arcasoy, S.; Sonett, J.R.; Robbins, H.; Shah, L.; Costa, J.; et al. Donor surfactant protein A2 polymorphism and lung transplant survival. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, F.X.; Festa, A.L.; Andrews, R.P.; Linke, M.; Walzer, P.D. The carbohydrate recognition domain of surfactant protein A mediates binding to the major surface glycoprotein of Pneumocystis carinii. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 8092–8099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, C.; Sano, H.; Shimizu, T.; Mitsuzawa, H.; Nishitani, C.; Himi, T.; Kuroki, Y. Surfactant protein A directly interacts with TLR4 and MD-2 and regulates inflammatory cellular response. Importance of supratrimeric oligomerization. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 21771–21780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floros, J.; Wang, G. A point of view: Quantitative and qualitative imbalance in disease pathogenesis; pulmonary surfactant protein A genetic variants as a model. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part. Amol. Integr. Physiol. 2001, 129, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caracta, C.F. Gender differences in pulmonary disease. Mt. Sinai J. Med. New York 2003, 70, 215–224. [Google Scholar]

- Mudway, I.S.; Kelly, F.J. An investigation of inhaled ozone dose and the magnitude of airway inflammation in healthy adults. Am. J. Respir Crit Care Med. 2004, 169, 1089–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, A.; Churg, A.; Wright, J.L.; Zhou, S.; Kirby, M.; Coxson, H.O.; Lam, S.; Man, S.F.; Sin, D.D. Sex Differences in Airway Remodeling in a Mouse Model of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 2016, 193, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.M.; Thach, T.Q.; Chau, P.Y.; Chan, E.K.; Chung, R.Y.; Ou, C.Q.; Yang, L.; Peiris, J.S.; Thomas, G.N.; Lam, T.H.; et al. Part 4. Interaction between air pollution and respiratory viruses: Time-series study of daily mortality and hospital admissions in Hong Kong. Res. Rep. 2010, 283–362. [Google Scholar]

- Mikerov, A.N.; Hu, S.; Durrani, F.; Gan, X.; Wang, G.; Umstead, T.M.; Phelps, D.S.; Floros, J. Impact of sex and ozone exposure on the course of pneumonia in wild type and SP-A (-/-) mice. Microb. Pathog. 2012, 52, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Durrani, F.; Phelps, D.S.; Weisz, J.; Silveyra, P.; Hu, S.; Mikerov, A.N.; Floros, J. Gonadal hormones and oxidative stress interaction differentially affects survival of male and female mice after lung Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Exp. Lung Res. 2012, 38, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, R.; Umstead, T.M.; Freeman, W.M.; Floros, J.; Phelps, D.S. The impact of surfactant protein-A on ozone-induced changes in the mouse bronchoalveolar lavage proteome. Proteome Sci. 2009, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P.; Hoek, G.; Brunekreef, B.; Verhoeff, A.; van Wijnen, J. Air pollution and mortality in The Netherlands: Are the elderly more at risk? Eur. Respir. J. Suppl. 2003, 40, 34s–38s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Ramón, M.; Zanobetti, A.; Schwartz, J. The effect of ozone and PM10 on hospital admissions for pneumonia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A national multicity study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 163, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, J.L.; Tolbert, P.E.; Klein, M.; Metzger, K.B.; Flanders, W.D.; Todd, K.; Mulholland, J.A.; Ryan, P.B.; Frumkin, H. Ambient air pollution and respiratory emergency department visits. Epidemiology 2005, 16, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, E.; Warshauer, D.; Lippert, W.; Tarkington, B. Ozone and nitrogen dioxide exposure: Murine pulmonary defense mechanisms. Arch. Env. Health 1974, 28, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarkington, B.K.; Duvall, T.R.; Last, J.A. Ozone exposure of cultured cells and tissues. Methods Enzym. 1994, 234, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkington, B.K.; Wu, R.; Sun, W.M.; Nikula, K.J.; Wilson, D.W.; Last, J.A. In vitro exposure of tracheobronchial epithelial cells and of tracheal explants to ozone. Toxicology 1994, 88, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grippi, M.A.; Elias, J.A.; Fishman, J.A.; Kotloff, R.M.; Pack, A.I.; Senior, R.M. Physiological principles of normal lung function. In Fishman’s Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders; 5th ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 137–218. [Google Scholar]

- Dysart, K.; Miller, T.L.; Wolfson, M.R.; Shaffer, T.H. Research in high flow therapy: Mechanisms of action. Respir. Med. 2009, 103, 1400–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, N.; Tobin, A. High flow nasal oxygen generates positive airway pressure in adult volunteers. Aust. Crit. Care Off. J. Confed. Aust. Crit. Care Nurses 2007, 20, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, G.; Vaquero, C.; Colinas, L.; Cuena, R.; González, P.; Canabal, A.; Sanchez, S.; Rodriguez, M.L.; Villasclaras, A.; Fernández, R. Effect of Postextubation High-Flow Nasal Cannula vs Noninvasive Ventilation on Reintubation and Postextubation Respiratory Failure in High-Risk Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016, 316, 1565–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, M. High-Flow Nasal Cannula Oxygen Therapy in Adults: Physiological Benefits, Indication, Clinical Benefits, and Adverse Effects. Respir. Care 2016, 61, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, R.L.; Eccleston, M.L.; McGuinness, S.P. The effects of flow on airway pressure during nasal high-flow oxygen therapy. Respir. Care 2011, 56, 1151–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, J.E.; Williams, A.B.; Gerard, C.; Hockey, H. Evaluation of a humidified nasal high-flow oxygen system, using oxygraphy, capnography and measurement of upper airway pressures. Anaesth. Intensiv. Care 2011, 39, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, A.; Caruana, L.R.; Barnett, A.G.; Tronstad, O.; Fraser, J.F. Oxygen delivery through high-flow nasal cannulae increase end-expiratory lung volume and reduce respiratory rate in post-cardiac surgical patients. Br. J. Anaesth. 2011, 107, 998–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delorme, M.; Bouchard, P.A.; Simon, M.; Simard, S.; Lellouche, F. Effects of High-Flow Nasal Cannula on the Work of Breathing in Patients Recovering From Acute Respiratory Failure. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, 1981–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, M.G. High-Flow Nasal Cannula Oxygen in Adults: An Evidence-based Assessment. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2018, 15, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.M.; Nelson, S. Pulmonary host defenses and factors predisposing to lung infection. Clin. Chest Med. 2005, 26, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderink, R.G.; Waterer, G.W. Community-acquired pneumonia: Pathophysiology and host factors with focus on possible new approaches to management of lower respiratory tract infections. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 18, 743–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grippi, M.A.; Elias, J.A.; Fishman, J.A.; Kotloff, R.M.; Pack, A.I.; Senior, R.M. Lung immulogy. In Fishman’s Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 246–317. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, M.R.; Rosenkranz, P.; McCabe, K.; Rosen, J.E.; McAneny, D. I COUGH: Reducing postoperative pulmonary complications with a multidisciplinary patient care program. JAMA Surg. 2013, 148, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbock, A.; Mueller, E.; Netzer, S.; Gabriel, A.; Feindt, P.; Kindgen-Milles, D. Prophylactic nasal continuous positive airway pressure following cardiac surgery protects from postoperative pulmonary complications: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial in 500 patients. Chest 2009, 135, 1252–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floros, J.; Phelps, D.S. Is the role of lung innate immune molecules, SP-A1 and SP-A2, and of the alveolar macrophage being overlooked in COVID-19 diverse outcomes? PNEUMON 2020, 33, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

| Variants and Sex | † Young Infection (~450 CFU) | Aged Infection (~1800 CFU) | Aged-FA + Infection (~1800 CFU) | Aged-O3 + Infection (~1800 CFU) | O3/FA | * p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KO | Female | 47.16 | 15.09 | 71.23 | 5.19 | 7.29 | <0.05 |

| Male | 36.17 | 10.86 | 36.84 | 4.47 | 10.71 | ||

| 6A2 | Female | 79.06 | 21.21 | 100 | 14.28 | 11.11 | |

| Male | 48.64 | 3.12 | 100 | 14.28 | 16.66 | ||

| 6A4 | Female | 66.66 | 19.23 | 66.66 | 0 | 0 | |

| Male | 42.85 | 15.62 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1A0 | Female | 96.77 | 36.36 | 84.37 | 36.66 | 40.74 | |

| Male | 83.87 | 26.66 | 100 | 76.92 | 86.95 | ||

| 1A3 | Female | 85.71 | 19.44 | 88.88 | 0 | 0 | |

| Male | 46.87 | 15 | 100 | 50 | 71.42 | ||

| Male and Female combined | |||||||

| Variants | † Young mice (~450 CFU) | Aged infection (~1800 CFU) | Aged - FA + infection (~1800 CFU) | Aged - O3 + infection (~1800 CFU) | O3/FA | * p-Value | |

| KO | 42 | 13.13 | 53.69 | 4.86 | 8.75 | <0.05 | |

| 6A2 | 65 | 12.3 | 100 | 14.28 | 13.33 | ||

| 6A4 | 54.54 | 17.24 | 75 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1A0 | 90.32 | 30.76 | 90.9 | 55.35 | 62 | ||

| 1A3 | 68.91 | 17.1 | 93.75 | 23.8 | 33.33 | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thorenoor, N.; S. Phelps, D.; Kala, P.; Ravi, R.; Floros Phelps, A.; M. Umstead, T.; Zhang, X.; Floros, J. Impact of Surfactant Protein-A Variants on Survival in Aged Mice in Response to Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection and Ozone: Serendipity in Action. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8091276

Thorenoor N, S. Phelps D, Kala P, Ravi R, Floros Phelps A, M. Umstead T, Zhang X, Floros J. Impact of Surfactant Protein-A Variants on Survival in Aged Mice in Response to Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection and Ozone: Serendipity in Action. Microorganisms. 2020; 8(9):1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8091276

Chicago/Turabian StyleThorenoor, Nithyananda, David S. Phelps, Padma Kala, Radhika Ravi, Andreas Floros Phelps, Todd M. Umstead, Xuesheng Zhang, and Joanna Floros. 2020. "Impact of Surfactant Protein-A Variants on Survival in Aged Mice in Response to Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection and Ozone: Serendipity in Action" Microorganisms 8, no. 9: 1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8091276

APA StyleThorenoor, N., S. Phelps, D., Kala, P., Ravi, R., Floros Phelps, A., M. Umstead, T., Zhang, X., & Floros, J. (2020). Impact of Surfactant Protein-A Variants on Survival in Aged Mice in Response to Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection and Ozone: Serendipity in Action. Microorganisms, 8(9), 1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8091276