Assessment of Helicobacter pylori Prevalence in Fresh Raw Meat: Species and Source-Based Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Culture Conditions for Isolation and Recovery of H. pylori

2.3. Phenotypic Identification of Isolates

2.4. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

2.5. Nucleic Acid Extraction and Species-Specific PCR Assay

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth Pattern and Recovery on Selective Media

3.2. Detection and Prevalence of H. pylori

3.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility

3.4. Descriptive Statistics

3.5. Temporal Distribution of H. pylori Prevalence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheok, Y.Y.; Lee, C.Y.Q.; Cheong, H.C.; Vadivelu, J.; Looi, C.Y.; Abdullah, S.; Wong, W.F. An Overview of Helicobacter pylori survival tactics in the hostile human stomach environment. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, N.C.; Dambrosio, A. Helicobacter pylori: A foodborne pathogen? World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 3472–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ríos-Sandoval, M.; Quiñones-Aguilar, E.E.; Solís-Sánchez, G.A.; Bravo-Madrigal, J.; Velázquez-Guadarrama, N.; Rincón-Enríquez, G. Genotypes and Phylogenetic Analysis of Helicobacter pylori Clinical Bacterial Isolates. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 15, 1845–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogiel, T.; Mikucka, A.; Szaflarska-Popławska, A.; Grzanka, D. Usefulness of molecular methods for Helicobacter pylori detection in pediatric patients and their correlation with histopathological Sydney Classification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorani, M.; Tohumcu, E.; Del Vecchio, L.E.; Porcari, S.; Cammarota, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ianiro, G. The influence of Helicobacter pylori on human gastric and gut microbiota. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Cao, X.S.; Zhou, M.G.; Yu, B. Gastric microbiota in gastric cancer: Different roles of Helicobacter pylori and other microbes. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 12, 1105811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzia, K.A.; Aftab, H.; Miftahussurur, M.; Waskito, L.A.; Tuan, V.P.; Alfaray, R.I.; Matsumoto, T.; Yurugi, M.; Subsomwong, P.; Kabamba, E.T.; et al. Genetic determinants of Biofilm formation of Helicobacter pylori using whole-genome sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wu, D.; Cui, G.; Lee, K.H.; Yang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chua, E.G.; Chen, Z. Association Between Biofilm Formation and Structure and Antibiotic Resistance in H. pylori. Infect. Drug. Resist. 2024, 17, 2501–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Katelaris, P.; Hunt, R.; Bazzoli, F.; Cohen, H.; Fock, K.M.; Gemilyan, M.; Malfertheiner, P.; Mégraud, F.; Piscoya, A.; Quach, D.; et al. Helicobacter pylori: World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines; World Gastroenterology Organisation: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.worldgastroenterology.org/UserFiles/file/guidelines/helicobacter-pylori-english-2021.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Salih, B.A. Helicobacter pylori infection in developing countries: The burden for how long? Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Duynhoven, Y.T.; de Jonge, R. Transmission of Helicobacter pylori: A role for food? Bull World Health Organ 2001, 79, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central]

- Duan, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Dong, Y.; Han, Z.; Wan, M.; Lin, M.; Lin, B.; Kong, Q.; et al. Transmission routes and patterns of Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 2023, 28, e12945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almashhadany, D.A.; Mayas, S.M.; Omar, J.A.; Muslat, T.A.M. Frequency and seasonality of viable H. pylori in drinking water in Dhamar Governorate, Yemen. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2023, 12, 10855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, E.; Sheikhshahrokh, A. vacA genotype status of Helicobacter pylori isolated from foods with animal origin. Biomed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 8701067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pina-Pérez, M.C.; González, A.; Moreno, Y.; Ferrús, M.A. Helicobacter pylori detection in shellfish: A real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction approach. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2019, 16, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shrief, L.M.T.; Thabet, S.S. Isolation of Helicobacter pylori from raw milk and study on its survival in fermented milk products. J. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2022, 7, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Tajiri, Y.; Sata, M.; Fujii, Y.; Matsubara, F.; Zhao, M.; Shimizu, S.; Toyonaga, A.; Tanikawa, K. Helicobacter pylori in the natural environment. Scand J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 31, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queralt, N.; Bartolomé, R.; Araujo, R. Detection of Helicobacter pylori DNA in human faeces and water with different levels of faecal pollution in the north-east of Spain. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 98, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, C.P.; Codony, F.; Fittipaldi, M.; Sierra-Torres, C.H.; Morató, J. Monitoring levels of viable Helicobacter pylori in surface water by qPCR in Northeast Spain. J. Water Health. 2018, 16, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almagro-Martínez, C.; Alenda-Botella, A.; Botella-Juan, L. Systematic review on the zoonotic potential of Helicobacter pylori. Discov. Public Health 2025, 22, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, S.I.; Talat, D.; Khatab, S.A.; Nossair, M.A.; Ayoub, M.A.; Ewida, R.M.; Diab, M.S. An investigative study on the zoonotic potential of Helicobacter pylori. BMC Vet. Res. 2023, 19, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, A.J. Helicobacter. In Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 11th ed.; Jorgensen, J.H., Pfaller, M.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1013–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Almashhadany, D.A.; Mayas, S.M.; Ali, N.L. Isolation and identification of Helicobacter pylori from raw chicken meat in Dhamar Governorate, Yemen. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2022, 11, 10220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almashhadany, D.A.; Mayas, S.M.; Mohammed, H.I.; Hassan, A.A.; Khan, I.U.H. Population- and gender-based investigation for prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Dhamar, Yemen. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 2023, 3800810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mégraud, F.; Lehours, P. Helicobacter pylori detection and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 280–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 33rd ed.; CLSI supplement M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters; Version 13.0; European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Växjö, Sweden, 2020; Available online: https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Chaves, S.; Gadanho, M.; Tenreiro, R.; Cabrita, J. Assessment of metronidazole susceptibility in Helicobacter pylori by disk diffusion and E-test methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999, 37, 1628–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, C.L.; Kleanthous, H.; Coates, P.J.; Morgan, D.D.; Tabaqchali, S. Sensitive detection of Helicobacter pylori by using polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992, 30, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.J.; Wallace, R.L.; Smith, J.J.; Graham, T.; Saputra, T.; Symes, S.; Stylianopoulos, A.; Polkinghorne, B.G.; Kirk, M.D.; Glass, K. Prevalence of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni in retail chicken, beef, lamb, and pork products in three Australian states. J. Food Prot. 2019, 82, 2126–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrero, R.L.; Jenks, P.J. In Vivo Adaptation to the Host. In Helicobacter pylori: Physiology and Genetics; Mobley, H.L.T., Mendz, G.L., Hazell, S.L., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2450/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Jiang, X.; Doyle, M.P. Effect of environmental and substrate factors on survival and growth of Helicobacter pylori. J. Food Prot. 1998, 61, 929–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elrais, A.M.; Arab, W.S.; Sallam, K.I.; Elmegid, W.A.; Elgendy, F.; Elmonir, W.; Imre, K.; Morar, A.; Herman, V.; Elaadli, H. Prevalence, virulence genes, phylogenetic analysis, and antimicrobial resistance profile of Helicobacter species in chicken meat and their associated environment at retail shops in Egypt. Foods 2022, 11, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolomini, R.; Di Bonaventura, G.; Festi, D.; Catamo, G.; Laterza, F.; Neri, M. Optimal combination of media for primary isolation of Helicobacter pylori from gastric biopsy specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997, 35, 1541–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, T.H.; Lucia, L.M.; Acuff, G.R. Development of a selective medium for isolation of Helicobacter pylori from cattle and beef samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, R.P.H.; Walker, M.M. Epidemiology and diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. BMJ 2001, 323, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, J.C.; McNulty, C.A. Evaluation of a new selective medium for Campylobacter pylori. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infec. Dis. 1988, 7, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hortelano, I.; Moreno, Y.; Vesga, F.J.; Ferrús, M.A. Evaluation of different culture media for detection and quantification of H. pylori in environmental and clinical samples. Int. Microbiol. 2020, 23, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, A.; Razavilar, V.; Rokni, N.; Rahimi, E. vacA and cagA genotypes of Helicobacter pylori isolated from raw meat in Isfahan province, Iran. Vet. Res. Forum 2017, 8, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Momtaz, H.; Dabiri, H.; Souod, N.; Gholami, M. Study of Helicobacter pylori genotype status in cows, sheep, goats and human beings. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgohary, A.; Yousef, M.; Mohamed, A.; Abdel-Kareem, L.M. Epidemiological study on Helicobacter pylori in cattle and its milk with special reference to its zoonotic importance. Mansoura Vet. Med. J. 2015, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, M.; Elbehiry, A.; Marzouk, E.; Moussa, I.M.; Hessain, A.M.; Alhaji, J.H.; Heme, H.A.; Zahran, R.; Abdeen, E. Helicobacter pylori in a poultry slaughterhouse: Prevalence, genotyping and antibiotic resistance pattern. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, F.; Gheisari, E.; Dehkordi, F.S. Genotyping of vacA alleles of Helicobacter pylori strains recovered from some Iranian food items. Trop J. Pharm. Res. 2016, 15, 1631–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaei, R.; Souod, N.; Momtaz, H.; Dabiri, H. Milk of livestock as a possible transmission route of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2015, 8, S30–S36. [Google Scholar]

- Gillet, L.; Bénéjat, L.; Jehanne, Q.; Maunet, P.; Perreau, C.; Ducournau, A.; Aptel, J.; Jauvain, M.; Lehours, P. Resistome and virulome determination in Helicobacter pylori using next-generation sequencing with target-enrichment technology. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e03298-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; He, X.Y.; Tang, B.; Xiang, Y.; Yue, J.J. An improved quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction technology for Helicobacter pylori detection in stomach tissue and its application value in clinical precision testing. BMC Biotechnol. 2020, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fujimura, S.; Kawamura, T.; Kato, S.; Tateno, H.; Watanabe, A. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in cow’s milk. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 35, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atapoor, S.; Dehkordi, F.S.; Rahimi, E. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in various types of vegetables and salads. Jundishapur. J. Microbiol. 2014, 7, e10013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesga, F.J.; Moreno, Y.; Ferrús, M.A.; Campos, C.; Trespalacios, A.A. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in drinking water treatment plants in Bogotá, Colombia, using cultural and molecular techniques. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2018, 221, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sulami, A.A.; Al-Taee, A.M.; Juma’a, M.G. Isolation and identification of Helicobacter pylori from drinking water in Basra governorate, Iraq. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2010, 16, 920–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Dehkordi, F.S.; Rahimi, E. Virulence factors and antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori isolated from raw milk and unpasteurized dairy products in Iran. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 20, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Rahimi, E.; Shakerian, A. Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from raw poultry meat in the Shahrekord Region, Iran: Frequency and molecular characteristics. Genes 2023, 14, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademi, F.; Faghri, J.; Poursina, F.; Esfahani, B.N.; Moghim, S.; Fazeli, H.; Adibi, P.; Mirzaei, N.; Akbari, M.; Safaei, H.G. Resistance pattern of Helicobacter pylori strains to clarithromycin, metronidazole, and amoxicillin in Isfahan, Iran. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2013, 18, 1056–1060. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, A.; Gisbert, J.P.; McNamara, D.; O’Morain, C.; O’Morain, N. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection 2017. Helicobac 2017, 22, e12410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wouden, E.J.; Thijs, J.C.; Kusters, J.G.; van Zwet, A.A.; Kleibeuker, J.H. Mechanism and clinical significance of metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Scand J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 2001, 234, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, P.; Vashishth, R. Antimicrobial resistance in foodborne pathogens: Consequences for public health and future approaches. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Munawar, A.; Nawaz, Z.; Hussain, N.; Hafeez, A.B.; Szweda, P. Antibiotic resistance and preventive strategies in foodborne pathogenic bacteria: A comprehensive review. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 34, 2101–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šťástková, Z.; Navrátilová, P.; Gřondělová, A. Milk and dairy products as a possible source of environmental transmission of Helicobacter pylori. Acta Vet. Brno 2021, 90, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaghi, E.; Khamesipour, F.; Mashayekhi, F.; Safarpoor Dehkordi, F.; Sakhaei, M.H.; Masoudimanesh, M.; Khameneie, M.K. Helicobacter pylori in vegetables and salads: Genotyping and antimicrobial resistance properties. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 757941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Ferrús, M.; González, A.; Pina-Pérez, M.C.; Ferrús, M.A. Helicobacter pylori is present at quantifiable levels in raw vegetables in the Mediterranean area of Spain. Agriculture 2022, 12, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, J.T.; Gaddy, J.A.; Algood, H.M.S.; Gaudieri, S.; Mallal, S.; Cover, T.L. Helicobacter pylori adaptation in vivo in response to a high-salt diet. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, e00918-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zheng, T.; Shen, D.; Chen, J.; Pei, X. Research progress in the Helicobacter pylori with viable non-culturable state. J. Centr. S. Univer. Med. 2021, 46, 1423–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonezawa, H.; Osaki, T.; Kamiya, S. Biofilm formation by Helicobacter pylori and its involvement in antibiotic resistance. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 914791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

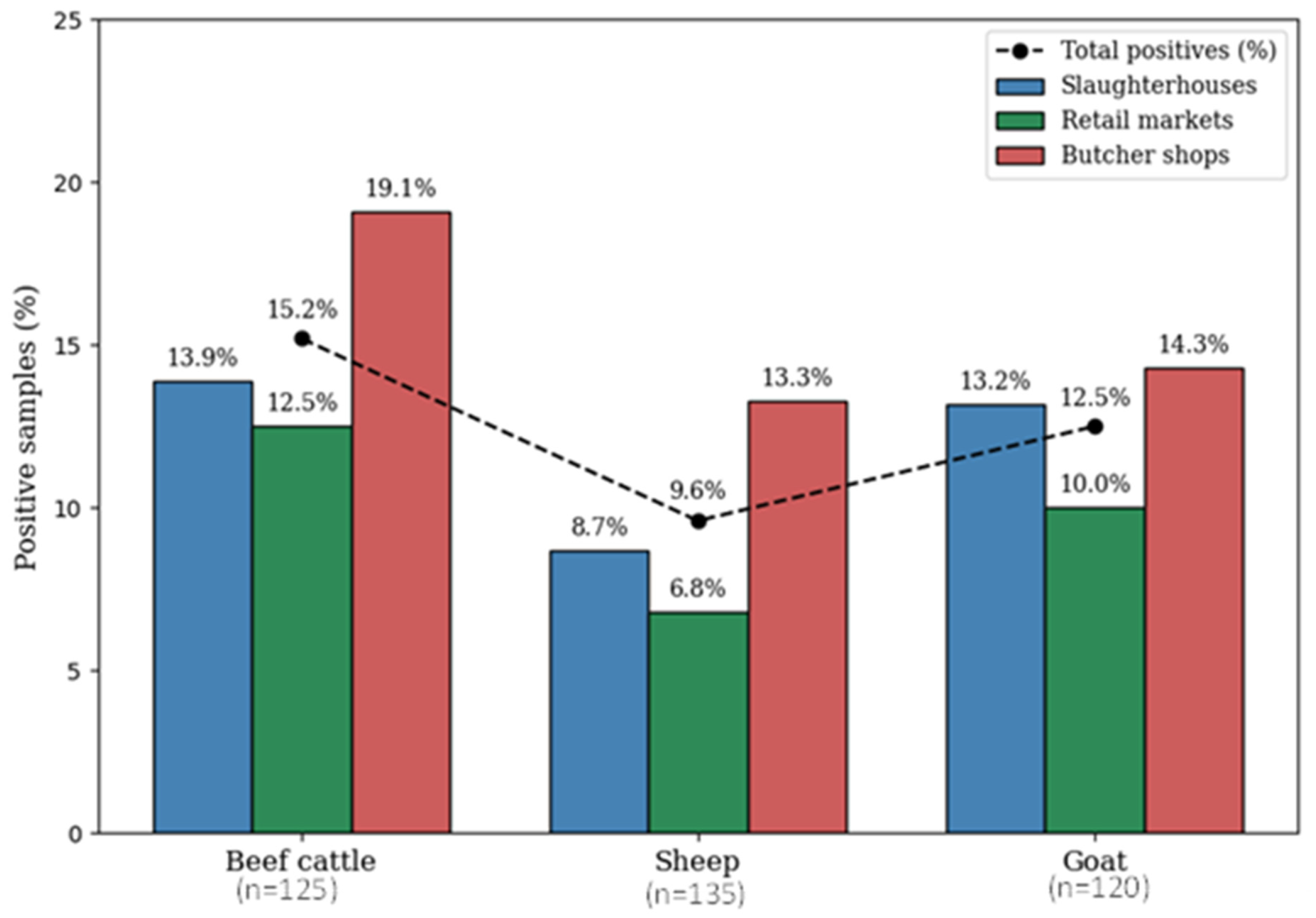

| Meat Type * (Number of Samples) | H. pylori Isolates § n (%) | Number of Samples/Positive Number (%) Based on Source of Sample ** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slaughterhouses (n = 127) | Retail Markets (n = 124) | Butcher Shops (n = 129) | ||

| Beef cattle (n = 125) | 19 (15.2) | 43/6 (13.9) | 40/5 (12.5) | 42/8 (19.1) |

| Sheep (n = 135) | 13 (9.6) | 46/4 (8.7) | 44/3 (6.8) | 45/6 (13.3) |

| Goat (n = 120) | 15 (12.5) | 38/5 (13.2) | 40/4 (10) | 42/6 (14.3) |

| Total (n = 380) | 47 §§ (12.4) | 127/15 (11.8) | 124/12 (9.7) | 129/20 (15.5) |

| Antimicrobial Class | Antimicrobial Agent | Resistance Profile Based on Meat Source | Overall Resistance Profile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beef Cattle § n (%) | Sheep §§ n (%) | Goat §§§ n (%) | Resistant * n (%) | Intermediate n (%) | Susceptible n (%) | ||

| β-lactams (Penicillin) | Ampicillin (AMP, 10 µg) | 4 (21.1) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (20) | 9 (19.1) | 2 (4.3) | 36 (76.6) |

| Amoxicillin (AMX, 10 µg) | 4 (21.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (13.3) | 6 (12.8) | 3 (6.4) | 38 (80.8) | |

| Tetracyclines | Tetracycline (TE, 30 µg) | 6 (31.6) | 3 (23.1) | 4 (26.7) | 13 (27.7) | 5 (10.6) | 29 (61.7) |

| Macrolides | Erythromycin (E, 15 µg) | 9 (47.4) | 2 (15.4) | 6 (40) | 17 (36.2) | 7 (14.9) | 23 (48.9) |

| Clarithromycin (CLR, 15 µg) | 4 (21.1) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (13.3) | 7 (14.9) | 5 (10.6) | 35 (74.5) | |

| Azithromycin (AZM, 30 µg) | 5 (26.3) | 2 (15.4) | 4 (26.7 | 11 (23.4) | 7 (14.9) | 29 (61.7) | |

| Nitroimidazoles | Metronidazole (MT, 5 µg) | 11 (57.9) | 3 (23.1) | 5 (33.3) | 19 (40.4) | 3 (6.4) | 25 (53.2) |

| Fluoroquinolones | Levofloxacin (LE, 5 µg) | 3 (15.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (26.7) | 7 (14.9) | 3 (6.4) | 37 (78.7) |

| Month § | Total Number of Samples | Number of Positive Samples (%) Based on Sample Source §§ | Number of Positive Samples (%) Based on Meat Types §§§ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slaughterhouses (n = 127) | Retail Markets (n = 124) | Butcher Shops (n = 129) | Total (n = 380) | Beef Cattle (n = 125) | Sheep (n = 135) | Goat (n = 120) | Total (n = 380) | ||

| January | 62 | 2 (3.2) * | 1 (1.6) | 2 (3.2) | 5 (8.1) | 2 (3.2) * | 1 (1.6) | 2 (3.2) | 5 (8.1) |

| February | 63 | 2 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.2) | 4 (6.3) | 1 (1.6) | 2 (3.2) | 1 (1.6) | 4 (6.3) |

| March | 63 | 0 (0) | 3 (4.8) | 1 (1.6) | 4 (6.3) | 3 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | 4 (6.3) |

| April | 65 | 4 (6.2) | 3 (4.6) | 6 (9.2) | 13 (20) | 5 (7.7) | 4 (6.2) | 4 (6.2) | 13 (20) |

| May | 65 | 3 (4.6) | 3 (4.6) | 5 (7.7) | 11 (16.9) | 4 (6.2) | 3 (4.6) | 4 (6.2) | 11 (16.9) |

| June | 62 | 4 (6.5) | 2 (3.2) | 4 (6.5) | 10 (16.1) | 4 (6.5) | 3 (4.8) | 3 (4.8) | 10 (16.1) |

| Total | 380 | 15 (11.8) | 12 (9.7) | 20 (15.5) | 47 (12.4) | 19 (15.2) | 13 (9.6) | 15 (12.5) | 47 (12.4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Almashhadany, D.A.; Mayas, S.M.; Hassan, A.A.; Khan, I.U.H. Assessment of Helicobacter pylori Prevalence in Fresh Raw Meat: Species and Source-Based Analysis. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020379

Almashhadany DA, Mayas SM, Hassan AA, Khan IUH. Assessment of Helicobacter pylori Prevalence in Fresh Raw Meat: Species and Source-Based Analysis. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(2):379. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020379

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmashhadany, Dhary A., Sara M. Mayas, Abdulwahed A. Hassan, and Izhar U. H. Khan. 2026. "Assessment of Helicobacter pylori Prevalence in Fresh Raw Meat: Species and Source-Based Analysis" Microorganisms 14, no. 2: 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020379

APA StyleAlmashhadany, D. A., Mayas, S. M., Hassan, A. A., & Khan, I. U. H. (2026). Assessment of Helicobacter pylori Prevalence in Fresh Raw Meat: Species and Source-Based Analysis. Microorganisms, 14(2), 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020379