GlnK Regulates the Type III Secretion System by Modulating NtrB-NtrC Homeostasis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Media

2.2. Ethics Statement

2.3. Mouse Pneumonia Model and Analysis

2.4. RNA Extraction and Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.5. β-Galactosidase Activity Assay

2.6. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

2.7. RNA-Seq and Data Analysis

2.8. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.9. Western Blotting

2.10. Affinity Chromatography Purification–Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS)

2.11. Co-Purification Assay

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

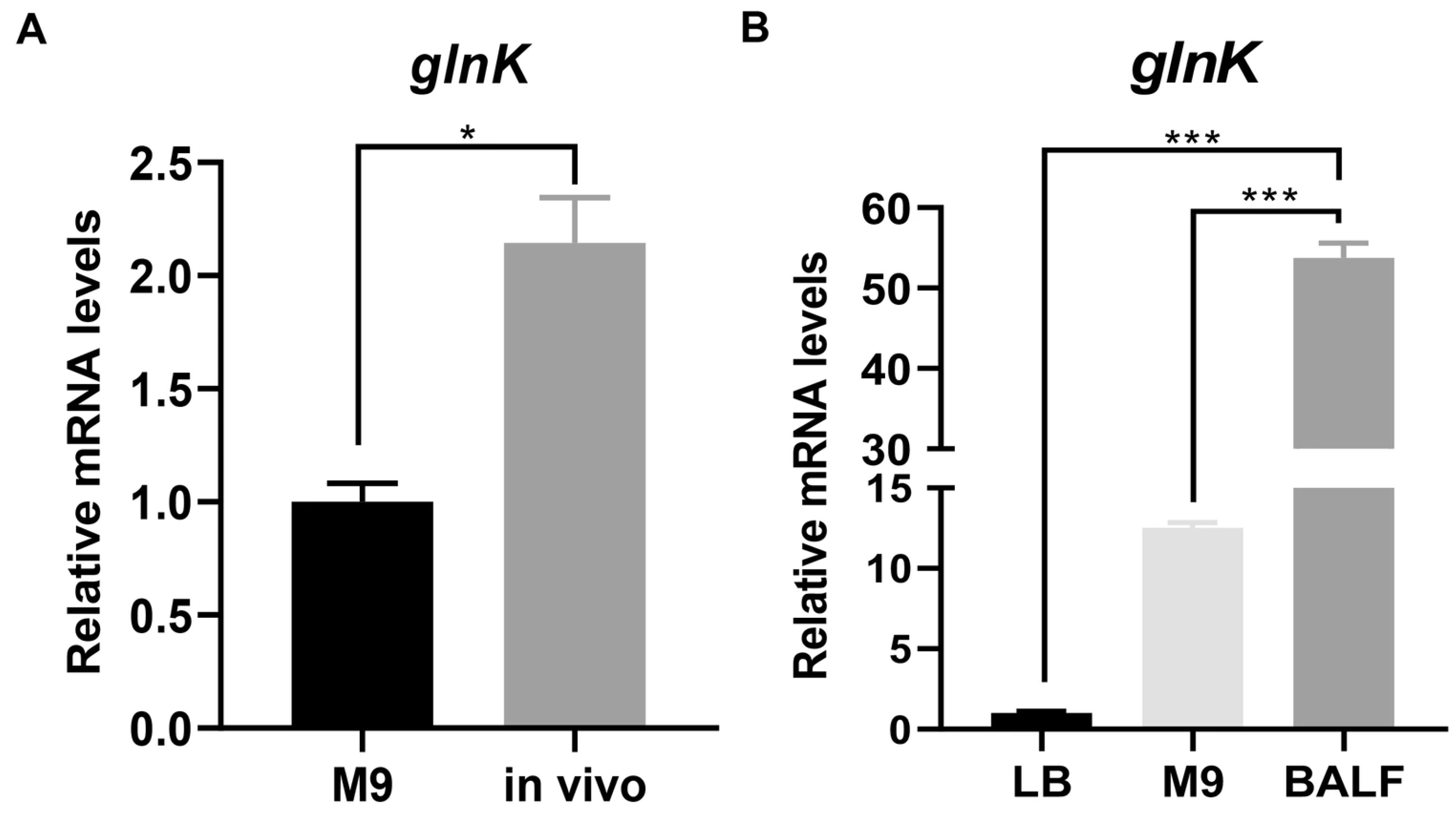

3.1. The glnK Gene Is Upregulated in Response to the Mouse Lung Environment

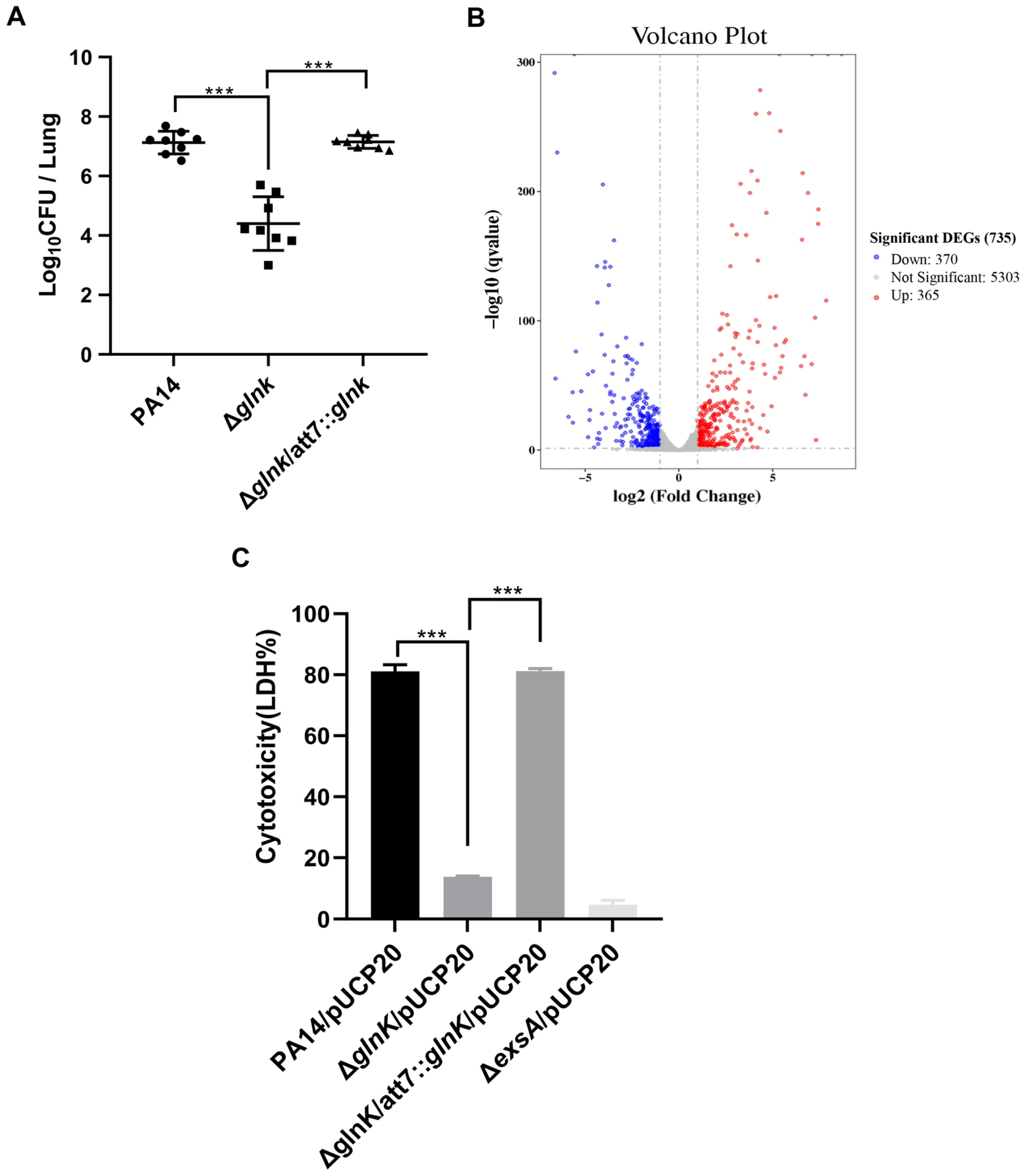

3.2. Glnk Regulates Bacterial Virulence

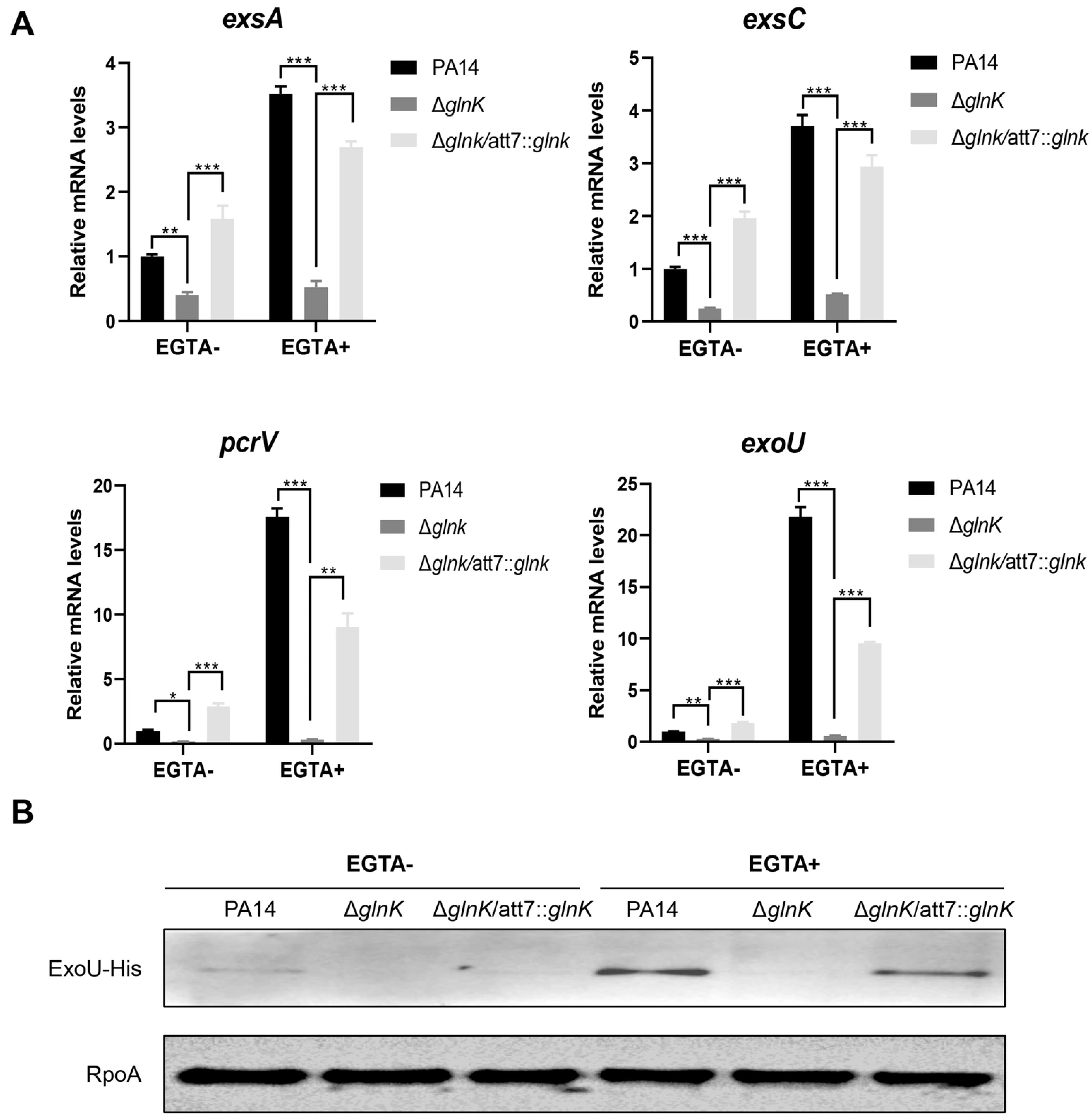

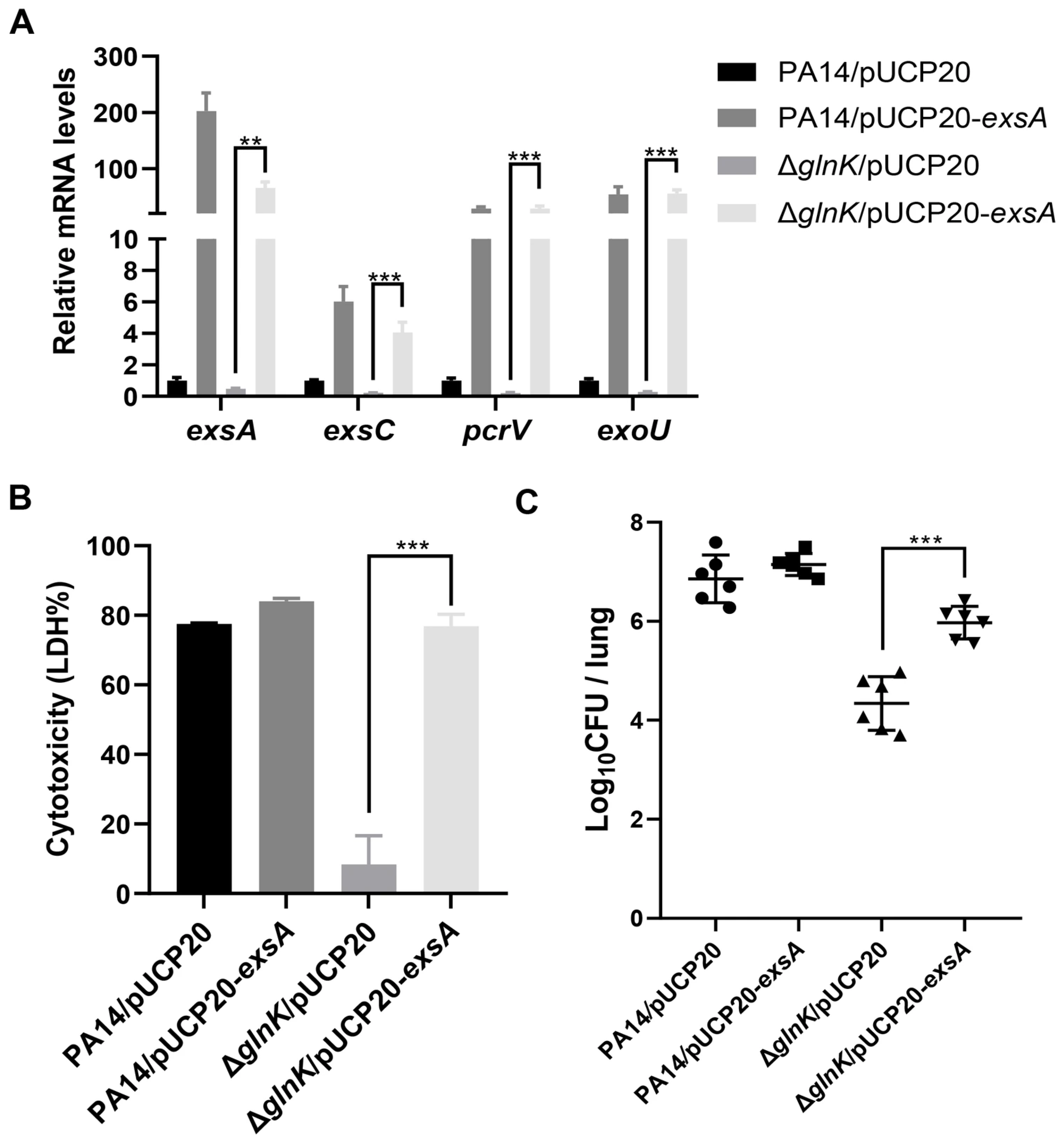

3.3. GlnK Is Required for the Expression of the T3SS

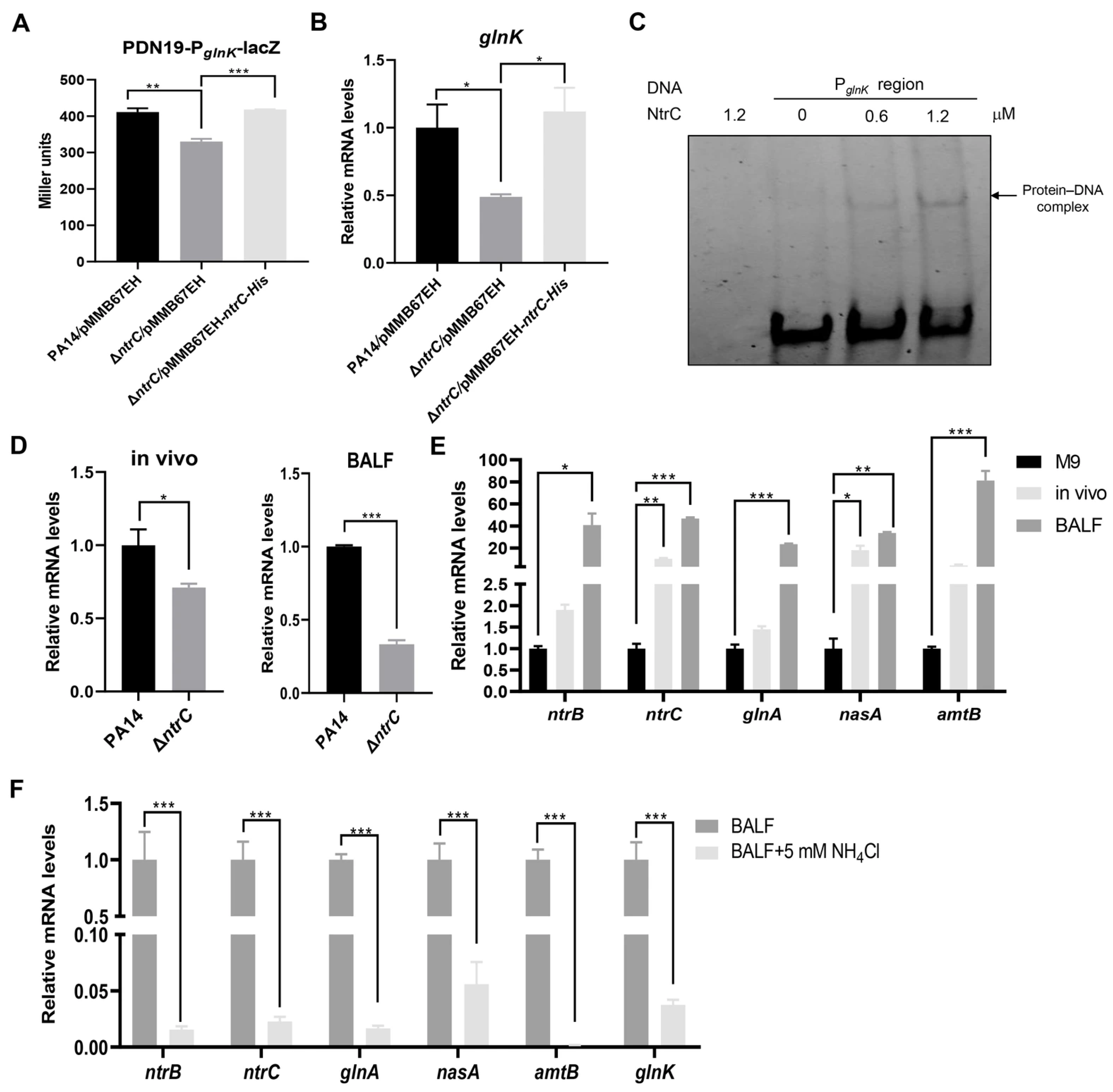

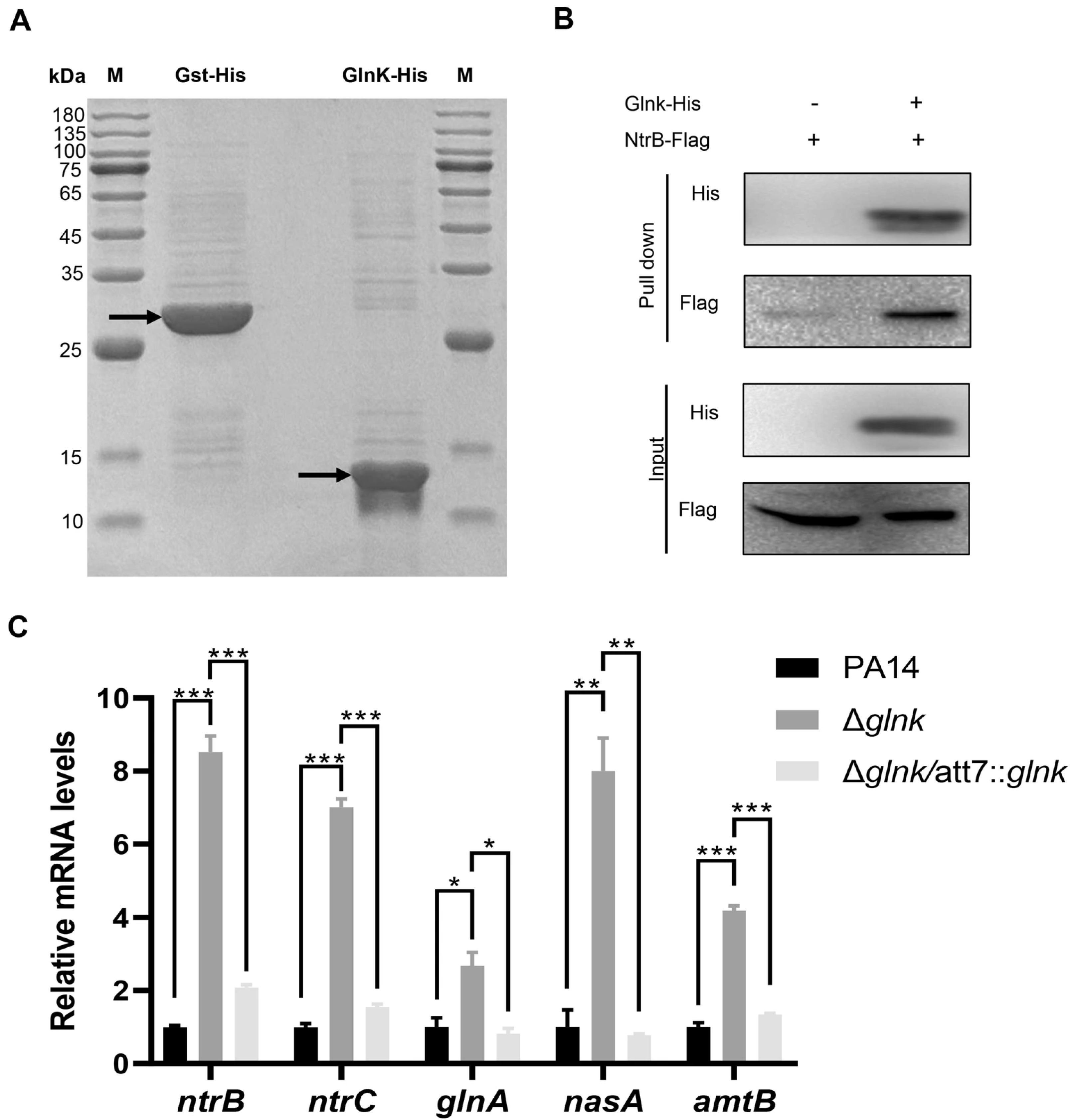

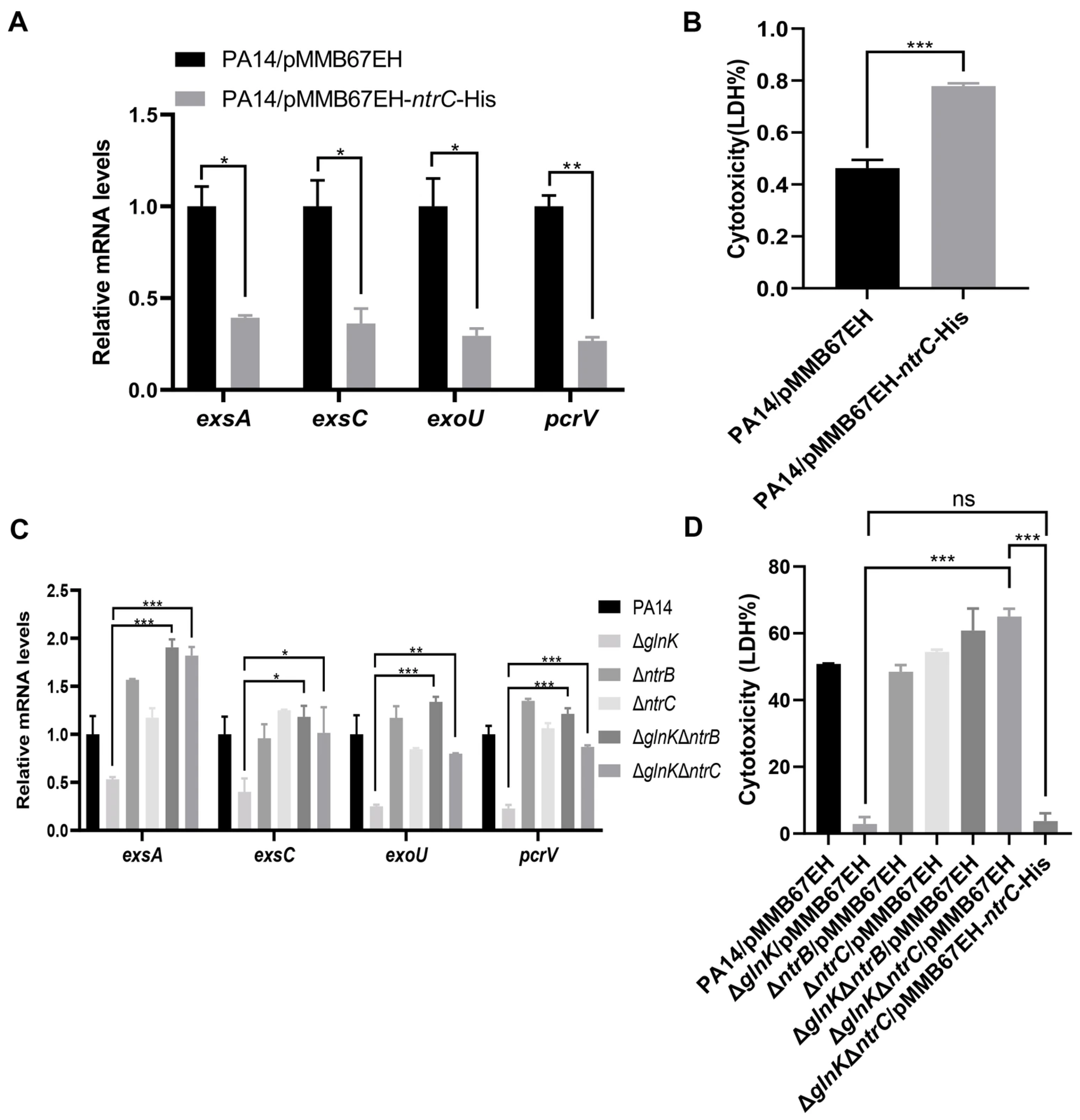

3.4. GlnK Controls the T3SS by Regulating the NtrB/NtrC Two-Component System Through a Negative Feedback Mechanism

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T3SS | Type III secretion system |

| MOI | Multiplicity of infection |

References

- Jault, P.; Leclerc, T.; Jennes, S.; Pirnay, J.P.; Que, Y.A.; Resch, G.; Rousseau, A.F.; Ravat, F.; Carsin, H.; Le Floch, R.; et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a cocktail of bacteriophages to treat burn wounds infected by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PhagoBurn): A randomised, controlled, double-blind phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouget, C.; Dunyach-Remy, C.; Magnan, C.; Pantel, A.; Sotto, A.; Lavigne, J.P. Polymicrobial Biofilm Organization of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a Chronic Wound Environment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, I.; Kahan-Hanum, M.; Buchstab, N.; Zelcbuch, L.; Navok, S.; Sherman, I.; Nicenboim, J.; Axelrod, T.; Berko-Ashur, D.; Olshina, M.; et al. Phage therapy with nebulized cocktail BX004-A for chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in cystic fibrosis: A randomized first-in-human trial. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scribani Rossi, C.; Barrientos-Moreno, L.; Paone, A.; Cutruzzola, F.; Paiardini, A.; Espinosa-Urgel, M.; Rinaldo, S. Nutrient Sensing and Biofilm Modulation: The Example of L-arginine in Pseudomonas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Shao, S. Roles of virulence regulator ToxR in viable but non-culturable formation by controlling reactive oxygen species resistance in pathogen Vibrio alginolyticus. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 254, 126900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matz, C.; Moreno, A.M.; Alhede, M.; Manefield, M.; Hauser, A.R.; Givskov, M.; Kjelleberg, S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses type III secretion system to kill biofilm-associated amoebae. ISME J. 2008, 2, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuven, A.D.; Katzenell, S.; Mwaura, B.W.; Bliska, J.B. ExoS effector in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Hyperactive Type III secretion system mutant promotes enhanced Plasma Membrane Rupture in Neutrophils. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1013021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brutinel, E.D.; King, J.M.; Marsden, A.E.; Yahr, T.L. The distal ExsA-binding site in Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion system promoters is the primary determinant for promoter-specific properties. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 2564–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams McMackin, E.A.; Djapgne, L.; Corley, J.M.; Yahr, T.L. Fitting Pieces into the Puzzle of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Type III Secretion System Gene Expression. J. Bacteriol. 2019, 201, e00209-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gong, X.; Fan, Z.; Xia, Y.; Jin, Y.; Bai, F.; Cheng, Z.; Pan, X.; Wu, W. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Citrate Synthase GltA Influences Antibiotic Tolerance and the Type III Secretion System through the Stringent Response. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0323922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, N.; Ashare, A.; Hunninghake, G.W.; Yahr, T.L. Transcriptional induction of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion system by low Ca2+ and host cell contact proceeds through two distinct signaling pathways. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 3334–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanowski, M.L.; Lykken, G.L.; Yahr, T.L. A secreted regulatory protein couples transcription to the secretory activity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 9930–9935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakulskas, C.A.; Brady, K.M.; Yahr, T.L. Mechanism of transcriptional activation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExsA. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 6654–6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, S.J.; Hoffman, K.M.; Flynn, J.M.; Wiggen, T.D.; Lucas, S.K.; Villarreal, A.R.; Gilbertsen, A.J.; Dunitz, J.M.; Hunter, R.C. Host- and microbial-mediated mucin degradation differentially shape Pseudomonas aeruginosa physiology and gene expression. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1013568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Fan, Z.; Chen, L.; Liu, C.; Bai, F.; Wei, Y.; Tian, Z.; Dong, Y.; Shi, J.; Chen, H.; et al. PvrA is a novel regulator that contributes to Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis by controlling bacterial utilization of long chain fatty acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 5967–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Liang, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, L.; Yue, Z.; Yin, L.; Jin, Y.; Bai, F.; Cheng, Z.; et al. Regulatory and structural mechanisms of PvrA-mediated regulation of the PQS quorum-sensing system and PHA biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 2691–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuypers, M.M.M.; Marchant, H.K.; Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Heeswijk, W.C.; Westerhoff, H.V.; Boogerd, F.C. Nitrogen assimilation in Escherichia coli: Putting molecular data into a systems perspective. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013, 77, 628–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, S.P.; Purich, D.; Stadtman, E.R. Cascade control of Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase. Properties of the PII regulatory protein and the uridylyltransferase-uridylyl-removing enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1975, 250, 6264–6272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolay, P.; Rozbeh, R.; Muro-Pastor, M.I.; Timm, S.; Hagemann, M.; Florencio, F.J.; Forchhammer, K.; Klahn, S. The Novel P(II)-Interacting Protein PirA Controls Flux into the Cyanobacterial Ornithine-Ammonia Cycle. mBio 2021, 12, e00229-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosztolai, A.; Schumacher, J.; Behrends, V.; Bundy, J.G.; Heydenreich, F.; Bennett, M.H.; Buck, M.; Barahona, M. GlnK Facilitates the Dynamic Regulation of Bacterial Nitrogen Assimilation. Biophys. J. 2017, 112, 2219–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javelle, A.; Severi, E.; Thornton, J.; Merrick, M. Ammonium sensing in Escherichia coli. Role of the ammonium transporter AmtB and AmtB-GlnK complex formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 8530–8538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro-Roig, L.; Lange, C.; Bonete, M.J.; Soppa, J.; Maupin-Furlow, J. Nitrogen regulation of protein-protein interactions and transcript levels of GlnK PII regulator and AmtB ammonium transporter homologs in Archaea. MicrobiologyOpen 2013, 2, 826–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, E.C.M.; Parize, E.; Gravina, F.; Pontes, F.L.D.; Santos, A.R.S.; Araujo, G.A.T.; Goedert, A.C.; Urbanski, A.H.; Steffens, M.B.R.; Chubatsu, L.S.; et al. The Protein-Protein Interaction Network Reveals a Novel Role of the Signal Transduction Protein PII in the Control of c-di-GMP Homeostasis in Azospirillum brasilense. mSystems 2020, 5, e00817-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Tang, M.; Chen, J.; Yang, T.; Zhang, X.; Shao, M.; Xu, Z.; Rao, Z. PII Signal Transduction Protein GlnK Alleviates Feedback Inhibition of N-Acetyl-l-Glutamate Kinase by l-Arginine in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00039-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokorzynski, N.A.-O.; Groisman, E.A.-O. How Bacterial Pathogens Coordinate Appetite with Virulence. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2023, 87, e0019822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.H.; Schweizer, H.P. Mini-Tn7 insertion in bacteria with single attTn7 sites: Example Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Z.; Bennett, R.C.; Lin, J.A.-O.; Hao, Y.; Zhu, L.A.-O.; Akinbi, H.T.; Lau, G.W. Surfactant phospholipids act as molecular switches for premature induction of quorum sensing-dependent virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Virulence 2020, 11, 1090–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Weng, Y.; Li, X.; Yue, Z.; Chai, Z.; Zhang, X.; Gong, X.; Pan, X.A.-O.; Jin, Y.; Bai, F.; et al. Acetylation of the CspA family protein CspC controls the type III secretion system through translational regulation of exsA in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 6756–6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Yin, L.; Qin, S.; Sun, X.; Gong, X.; Li, S.; Pan, X.; Jin, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Jin, S.; et al. Identification of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa AgtR-CspC-RsaL pathway that controls Las quorum sensing in response to metabolic perturbation and Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1013054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huergo, L.F.; Chubatsu, L.S.; Souza, E.M.; Pedrosa, F.O.; Steffens, M.B.R.; Merrick, M. Interactions between PII proteins and the nitrogenase regulatory enzymes DraT and DraG in Azospirillum brasilense. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 5232–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervas, A.B.; Canosa, I.; Little, R.; Dixon, R.; Santero, E. NtrC-dependent regulatory network for nitrogen assimilation in Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 6123–6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, J.; Behrends, V.; Pan, Z.; Brown, D.R.; Heydenreich, F.; Lewis, M.R.; Bennett, M.H.; Razzaghi, B.; Komorowski, M.; Barahona, M.; et al. Nitrogen and carbon status are integrated at the transcriptional level by the nitrogen regulator NtrC in vivo. mBio 2013, 4, e00881-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, M.A.; Baquir, B.; An, A.; Choi, K.G.; Hancock, R.E.W. NtrBC Selectively Regulates Host-Pathogen Interactions, Virulence, and Ciprofloxacin Susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 694789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Gil, T.; Cuesta, T.; Hernando-Amado, S.; Reales-Calderon, J.A.; Corona, F.; Linares, J.F.; Martinez, J.L. Virulence and Metabolism Crosstalk: Impaired Activity of the Type Three Secretion System (T3SS) in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa Crc-Defective Mutant. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietsch, A.; Wolfgang, M.C.; Mekalanos, J.J. Effect of metabolic imbalance on expression of type III secretion genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Peisach, D.; Pioszak, A.A.; Xu, Z.; Ninfa, A.J. Crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of the two-component system transmitter protein nitrogen regulator II (NRII.; NtrB), regulator of nitrogen assimilation in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 6670–6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.R.; Kamberov, E.S.; Weiss, R.L.; Ninfa, A.J. Reversible uridylylation of the Escherichia coli PII signal transduction protein regulates its ability to stimulate the dephosphorylation of the transcription factor nitrogen regulator I (NRI or NtrC). J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 28288–28293. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, M.R.; Ninfa, A.J. Characterization of the GlnK protein of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 32, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurist-Doutsch, S.; Arrieta, M.C.; Tupin, A.; Valdez, Y.; Antunes, L.C.; Yen, R.; Finlay, B.B. Nutrient Deprivation Affects Salmonella Invasion and Its Interaction with the Gastrointestinal Microbiota. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.H.; Zhang, X.F.; Zhang, L.H. The global regulator Crc plays a multifaceted role in modulation of type III secretion system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. MicrobiologyOpen 2013, 2, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malecka, E.M.; Bassani, F.; Dendooven, T.; Sonnleitner, E.; Rozner, M.; Albanese, T.G.; Resch, A.; Luisi, B.; Woodson, S.; Blasi, U. Stabilization of Hfq-mediated translational repression by the co-repressor Crc in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 7075–7087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnleitner, E.; Wulf, A.; Campagne, S.; Pei, X.Y.; Wolfinger, M.T.; Forlani, G.; Prindl, K.; Abdou, L.; Resch, A.; Allain, F.H.; et al. Interplay between the catabolite repression control protein Crc, Hfq and RNA in Hfq-dependent translational regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 1470–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnleitner, E.; Abdou, L.; Haas, D. Small RNA as global regulator of carbon catabolite repression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21866–21871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishijyo, T.; Haas, D.; Itoh, Y. The CbrA-CbrB two-component regulatory system controls the utilization of multiple carbon and nitrogen sources in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 40, 917–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene ID | Gene Name | Description | log2FC a |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA14_42250 | pscL | T3SS stator protein PscL | −1.18 |

| PA14_42260 | pscK | T3SS sorting platform protein PscK | −1.35 |

| PA14_42270 | pscJ | T3SS inner membrane ring lipoprotein PscJ | −1.06 |

| PA14_42280 | pscI | T3SS inner rod subunit PscI | −0.91 |

| PA14_42290 | pscH | T3SS polymerization control protein PscH | −1.53 |

| PA14_42300 | pscG | T3SS chaperone PscG | −1.68 |

| PA14_42310 | pscF | T3SS needle filament protein PscF | −1.15 |

| PA14_42320 | pscE | T3SS co-chaperone PscE | −2.54 |

| PA14_42340 | pscD | T3SS inner membrane ring subunit PscD | −1.01 |

| PA14_42350 | pscC | T3SS outer membrane ring subunit PscC | −1.18 |

| PA14_42360 | pscB | T3SS chaperone PscB | −1.51 |

| PA14_42380 | exsD | T3SS regulon anti-activator ExsD | −1.18 |

| PA14_42390 | exsA | T3SS regulon transcriptional activator ExsA | −1.17 |

| PA14_42400 | exsB | T3SS pilotin ExsB | −1.79 |

| PA14_42410 | exsE | T3SS regulon translocated regulator ExsE | −2.12 |

| PA14_42430 | exsC | T3SS regulatory chaperone ExsC | −1.53 |

| PA14_42440 | popD | T3SS translocon subunit PopD | −2.27 |

| PA14_42450 | popB | T3SS translocon subunit PopB | −2.49 |

| PA14_42460 | pcrH | T3SS chaperone PcrH | −3.08 |

| PA14_42470 | pcrV | T3SS needle tip protein PcrV | −2.06 |

| PA14_42480 | pcrG | T3SS chaperone PcrG | −3.12 |

| PA14_42490 | pcrR | T3SS chaperone PcrR | −1.41 |

| PA14_42500 | pcrD | T3SS export apparatus subunit PcrD | −0.68 |

| PA14_42510 | pcr4 | T3SS chaperone | −2.09 |

| PA14_42530 | pcr2 | T3SS protein | −1.68 |

| PA14_42540 | pcr1 | T3SS gatekeeper subunit Pcr1 | −1.36 |

| PA14_42550 | popN | T3SS gatekeeper subunit PopN | −1.64 |

| PA14_42570 | pscN | T3SS ATPase PscN | −1.34 |

| PA14_42580 | pscO | T3SS central stalk protein PscO | −1.48 |

| PA14_42600 | pscP | T3SS needle length determinant PscP | −0.80 |

| PA14_42610 | pscQ | T3SS cytoplasmic ring protein PscQ | −0.67 |

| PA14_42620 | pscR | T3SS export apparatus subunit PscR | −0.80 |

| PA14_42630 | pscS | T3SS export apparatus subunit PscS | −3.32 |

| PA14_42640 | pscT | T3SS export apparatus subunit PscT | −0.78 |

| PA14_42660 | pscU | T3SS export apparatus subunit PscU | −1.03 |

| PA14_51530 | exoU | T3SS effector cytotoxin ExoU | −1.19 |

| PA14_00560 | exoT | T3SS effector bifunctional cytotoxin exoenzyme T | −1.77 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, X.; Du, Q.; Li, Y.; Gong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Jin, S.; Wu, W. GlnK Regulates the Type III Secretion System by Modulating NtrB-NtrC Homeostasis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020339

Sun X, Du Q, Li Y, Gong X, Zhang Y, Jin Y, Jin S, Wu W. GlnK Regulates the Type III Secretion System by Modulating NtrB-NtrC Homeostasis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(2):339. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020339

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Xiaomeng, Qitong Du, Yiming Li, Xuetao Gong, Yu Zhang, Yongxin Jin, Shouguang Jin, and Weihui Wu. 2026. "GlnK Regulates the Type III Secretion System by Modulating NtrB-NtrC Homeostasis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa" Microorganisms 14, no. 2: 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020339

APA StyleSun, X., Du, Q., Li, Y., Gong, X., Zhang, Y., Jin, Y., Jin, S., & Wu, W. (2026). GlnK Regulates the Type III Secretion System by Modulating NtrB-NtrC Homeostasis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microorganisms, 14(2), 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020339