A Novel Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Primer Set for Detecting the STY2879 Gene of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi in Raw Milk

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Primer Sets

2.2. Colorimetric LAMP Assay Construction

2.3. Controls

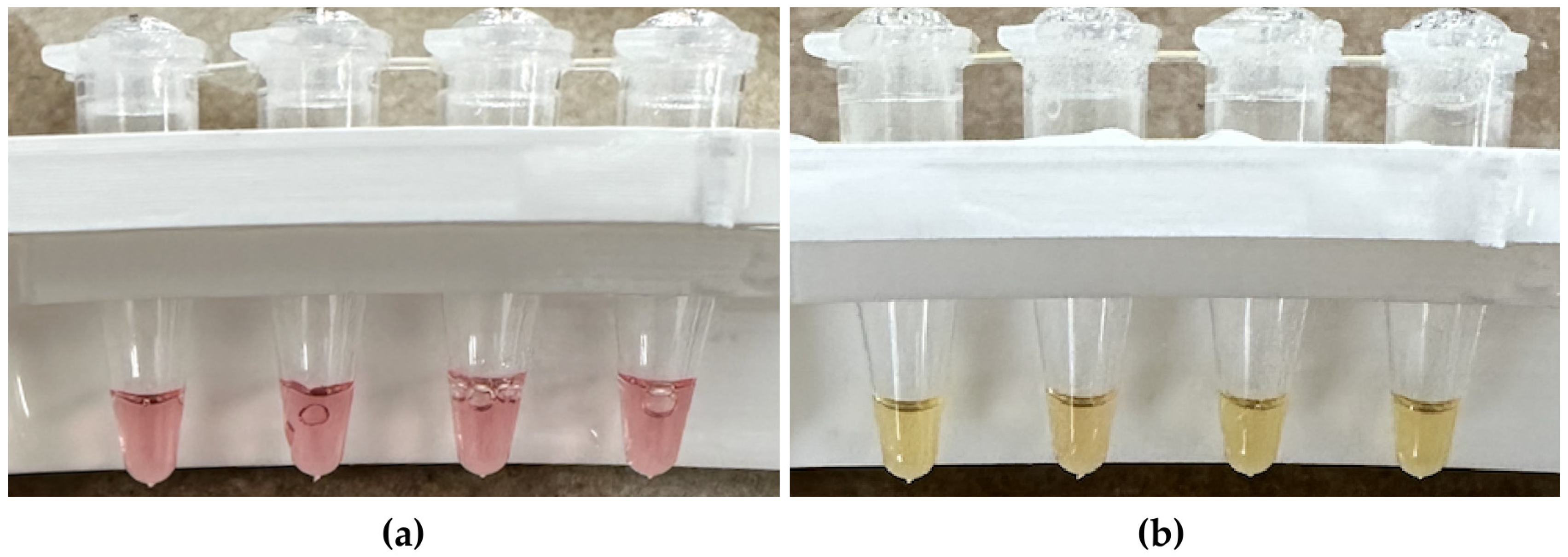

2.4. Incubating LAMP Reactions and Scoring Results

3. Results

3.1. Initial Screenings of Primer Sets

3.2. Validation of Novel Primer Set HJS-13-6

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DTT | Differential time to threshold (time difference full between negative control and positive control amplification) |

| LAMP | Loop-mediated isothermal amplification |

| F3 | Forward outer primer |

| B3 | Backward outer primer |

| FIP | Forward inner primer (composed of F1c and F2 regions) |

| BIP | Backward inner primer (composed of B1c and B2 regions) |

| LF | Loop forward primer |

| LB | Loop backward primer |

| PC | Positive control |

| NC | Non-template negative control |

| RXN | Reaction |

References

- Khan, M.; Shamim, S. Understanding the Mechanism of Antimicrobial Resistance and Pathogenesis of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiring, J.E.; Khanam, F.; Basnyat, B.; Charles, R.C.; Crump, J.A.; Debellut, F.; Holt, K.E.; Kariuki, S.; Mugisha, E.; Neuzil, K.M.; et al. Typhoid Fever. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2023, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loor-Giler, A.; Sanchez-Castro, C.; Robayo-Chico, M.; Puga-Torres, B.; Santander-Parra, S.; Nuñez, L. High Contamination of Salmonella Spp. in Raw Milk in Ecuador: Molecular Identification of Salmonella Enterica Serovars Typhi, Paratyphi, Enteritidis and Typhimurium. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1593266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, D.; Wu, F.; Havelaar, A.H. MILK Symposium Review: Foodborne Diseases from Milk and Milk Products in Developing Countries—Review of Causes and Health and Economic Implications. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 9715–9729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyokabi, S.; Luning, P.A.; De Boer, I.J.M.; Korir, L.; Muunda, E.; Bebe, B.O.; Lindahl, J.; Bett, B.; Oosting, S.J. Milk Quality and Hygiene: Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Smallholder Dairy Farmers in Central Kenya. Food Control 2021, 130, 108303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenu, K.; Wieland, B.; Szonyi, B.; Grace, D. Milk Handling Practices and Consumption Behavior among Borana Pastoralists in Southern Ethiopia. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2019, 38, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notomi, T. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.R.; Ryan, E.T. Diagnostics for Invasive Salmonella Infections: Current Challenges and Future Directions. Vaccine 2015, 33, C8–C15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snodgrass, R.; Gardner, A.; Semeere, A.; Kopparthy, V.L.; Duru, J.; Maurer, T.; Martin, J.; Cesarman, E.; Erickson, D. A Portable Device for Nucleic Acid Quantification Powered by Sunlight, a Flame or Electricity. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, S. Democratizing Nucleic Acid-Based Molecular Diagnostic Tests for Infectious Diseases at Resource-Limited Settings—From Point of Care to Extreme Point of Care. Sens. Diagn. 2024, 3, 536–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.; Kim, S. Inhibition of nonspecific Amplification in Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification via Tetramethylammonium Chloride. BioChip J. 2022, 16, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.S.; Bhadra, S.; Li, B.; Wu, Y.R.; Milligan, J.N.; Ellington, A.D. Robust Strand Exchange Reactions for the Sequence-Specific, Real-Time Detection of Nucleic Acid Amplicons. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 3314–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, J.; Saffie, N.; Sjasri, F.A.R.; Husin, A.; Abdul-Rahman, Z.; Ismail, A.; Aziah, I.; Mohamed, M. Rapid Detection of Salmonella Typhi by Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Method. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2014, 45, 1385–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, F.; Du, P.; Kan, B.; Yan, M. The Development and Evaluation of a Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Method for the Rapid Detection of Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhi. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, A.; Kapil, A.; Elangovan, R.; Jha, S.; Kalyanasundaram, D. Highly-Sensitive Detection of Salmonella Typhi in Clinical Blood Samples by Magnetic Nanoparticle-Based Enrichment and in-Situ Measurement of Isothermal Amplification of Nucleic Acids. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heamchandsaravanan, A.R.; Shanmugam, K.; Perumal, D.; Shankar, D.; Kalpana, S.; Dhandapani, P. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Assay Targeting STY2879 Gene for Rapid Detection of Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhi in Blood. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2024, 17, 2087–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New England Biolabs. NEB LAMP Primer Design. Available online: https://lamp.neb.com/#!/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Colosimo, F.; Tanner, N.A.; Patton, G.C.; New England Biolabs. LAMP Primer Design Using the NEB LAMP Primer Design Tool: Critical Considerations for Assay Robustness, Speed and Sensitivity; New England Biolabs: Ipswich, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamine, K.; Hase, T.; Notomi, T. Accelerated Reaction by Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Using Loop Primers. Mol. Cell. Probes 2002, 16, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oscorbin, I.; Filipenko, M. Bst Polymerase—A Humble Relative of Taq Polymerase. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 4519–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.-G.; Brewster, J.; Paul, M.; Tomasula, P. Two Methods for Increased Specificity and Sensitivity in Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification. Molecules 2015, 20, 6048–6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riyaz-Ul-Hassan, S.; Verma, V.; Qazi, G.N. Real-Time PCR-Based Rapid and Culture-Independent Detection of Salmonella in Dairy Milk—Addressing Some Core Issues. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 56, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| HJS-13-6 | Abdullah et al. [13] | Fan et al. [14] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| F3 | GAGATGATCACATCATCCATAC | TCTGGCACTCCTGTGCCTT | GCCAAATTGTTTGACGAGA |

| B3 | TATTCTCAAGCGCGGGAA | GCTCAAGACGAGAAACAGG | CTGTAAGAAACTTGTCCCATAG |

| FIP (F1c-F2) | GCAACCCTCTGCTTAGATAAAAGTT-ACACACACTTAGCTTGAGATC | TAGAAATAGTAGAGTCAGG-GCTTTTGCAGGTATTGTGG | TACTACGCCGATTGAACAAACAT-TGATCACATCATCCATAAACACA |

| BIP (B1c-B2) | TTGGAGATTGAACAAAACCAAAAGG-CATTTTCAACTGTAAGAAACTTGTC | TTGCCTTATCTAATACAAG-GTAAAAGGTGGTTTGCTCT | CTAAGCAGAGGGTTGCAAGTATT-CCACATAAGCATGTCCTCC |

| LF | TACTACGCCGATTGAACAAACATCA | ATGAAAAATGACGCGAGTT | None |

| LB | AGGACATGCTTATGTGGACTATGG | GTTGATCCTTTCAGTAAGG | None |

| Category | Parameter | Value/Range |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Conditions (mM) | Na+ concentration | 50 |

| Mg2+ concentration | 8 | |

| Primer Length (bp) | F1c/B1c | 20–22 |

| F2/B2 | 18–20 | |

| F3/B3 | 18–20 | |

| LF/LB | 15–25 | |

| Melting Temperature (°C) | F1c/B1c | 64–66 |

| F2/B2 | 59–61 | |

| F3/B3 | 59–61 | |

| LF/LB | 64–66 | |

| GC Content (%) | All primers | 40–65 |

| Loop primers | 40–65 | |

| Terminal Stability (ΔG, kcal·mol−1) | 5′ end | ≤−4 |

| 3′ end | ≤−4 | |

| 3′ end (loop primers) | ≤−2 | |

| Secondary Structure Thresholds (ΔG, kcal·mol−1) | Dimer check | ≤−2.5 |

| Dimer check (loop primers) | ≤−3.5 | |

| Inter-Primer Distances (bp) | F2-B2 (amplicon length) | 120–160 |

| F1c-F2 (loop region) | 40–60 | |

| F2-F3 | 0–60 | |

| F1c-B1c | 0–100 | |

| Primer Count Limits | F1c/B1c | ≤3 |

| F2/B2 | ≤10 | |

| F3/B3 | ≤3 | |

| LF/LB | ≤10 |

| Primer | 10X Stock (μM) | 1X Reaction (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| F3 | 2 | 0.2 |

| B3 | 2 | 0.2 |

| FIP | 16 | 1.6 |

| BIP | 16 | 1.6 |

| LF | 4 | 0.4 |

| LB | 4 | 0.4 |

| 2000 Ty2/RXN in 2% Raw Milk | 1000 Ty2/RXN in 1% Raw Milk | 2000 STY/RXN in 2% Raw Milk | 2000 STY/RXN in 2% Whole Milk | 2000 STY/RXN in H2O | 200,000 STY/RXN in H2O | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | PC | NC | PC | NC | PC | NC | PC | NC | PC | NC | PC | NC |

| Replicate Number | 10 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| 10 min | ||||||||||||

| 20 min | ||||||||||||

| 30 min | ||||||||||||

| 40 min | ||||||||||||

| 50 min | ||||||||||||

| 60 min | ||||||||||||

| 70 min | ||||||||||||

| PC | PC Concentration | Matrix | DTT (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA Isolated from S. Typhi strain Ty2 | 2000 genomes/reaction | 2% raw milk | 30 ± 5 |

| Genomic DNA Isolated from S. Typhi strain Ty2 | 1000 genomes/reaction | 1% raw milk | 20 ± 5 |

| Synthetic STY2879 | 2000 fragments/reaction | 2% raw milk | 30 ± 5 |

| Synthetic STY2879 | 2000 fragments/reaction | 2% whole milk | 20 ± 5 |

| Synthetic STY2879 | 2000 fragments/reaction | H2O | 30 ± 5 |

| Synthetic STY2879 | 200,000 fragments/reaction | H2O | 40 ± 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Seo, H.-J.; Riedel, T.E. A Novel Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Primer Set for Detecting the STY2879 Gene of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi in Raw Milk. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020297

Seo H-J, Riedel TE. A Novel Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Primer Set for Detecting the STY2879 Gene of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi in Raw Milk. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(2):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020297

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeo, Hyuck-Jin, and Timothy E. Riedel. 2026. "A Novel Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Primer Set for Detecting the STY2879 Gene of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi in Raw Milk" Microorganisms 14, no. 2: 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020297

APA StyleSeo, H.-J., & Riedel, T. E. (2026). A Novel Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Primer Set for Detecting the STY2879 Gene of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi in Raw Milk. Microorganisms, 14(2), 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020297