Interaction Between Duddingtonia flagrans and Pochonia chlamydosporia for the Biological Control of Bovine Gastrointestinal Nematodes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analyses

3. Results

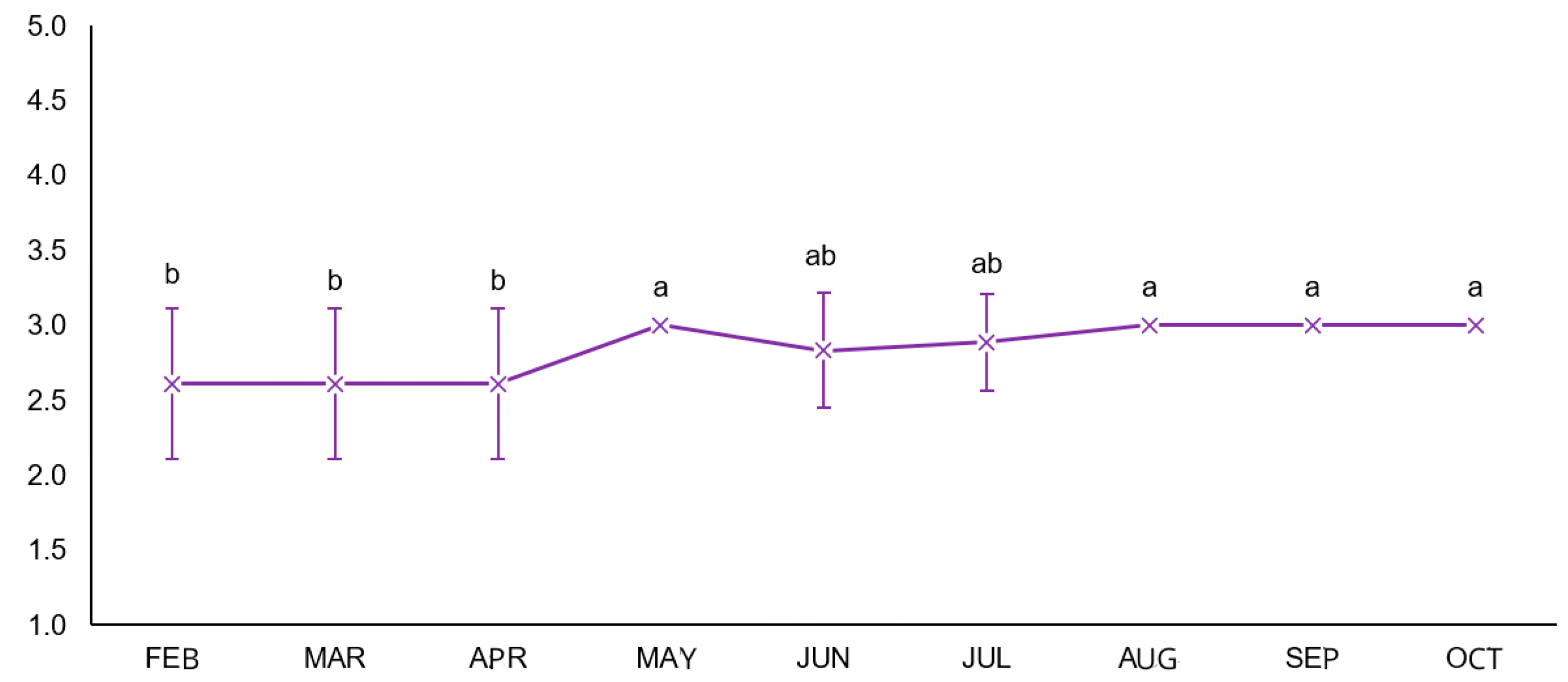

3.1. Body Condition Score (BCS)

3.2. Egg Counting Techniques

3.3. Larval Recovery Techniques

3.4. Environmental Conditions

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grisi, L.; Leite, R.C.; Martins, J.R.d.S.; de Barros, A.T.M.; Andreotti, R.; Cançado, P.H.D.; de León, A.A.P.; Pereira, J.B.; Villela, H.S. Reavaliação Do Potencial Impacto Econômico de Parasitos de Bovinos No Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária 2014, 23, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi-Storm, N.; Moakes, S.; Thüer, S.; Grovermann, C.; Verwer, C.; Verkaik, J.; Knubben-Schweizer, G.; Höglund, J.; Petkevičius, S.; Thamsborg, S.; et al. Parasite Control in Organic Cattle Farming: Management and Farmers’ Perspectives from Six European Countries. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2019, 18, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitencourt, V.M.L.; Viana, M.V.G.; Ito, M.; Trivilin, L.O. Isabella Vilhena Freire Martins Anti-Helmínticos de Importância Veterinária No Brasil. In Tópicos Especiais em Ciência Animal VIII; CAUFES: Alegre, Brazil, 2019; Volume VIII, pp. 273–297. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.M. Biology, Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Anthelmintic Resistance in Gastrointestinal Nematodes of Livestock. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2020, 36, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, F.E.d.F.; Lima, W.d.S.; Cunha, A.P.d.; Bello, A.C.P.d.P.; Domingues, L.N.; Wanderley, R.P.B.; Leite, P.V.B.; Leite, R.C. Verminoses dos bovinos: Percepção de pecuaristas em Minas Gerais, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2009, 18, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindicato Nacional da Indústria de Produtos para Saúde Animal Mercado Nacional de Produtos Para Saúde Animal. Mercado Nacional de Produtos para Saúde Animal. 2018. Available online: https://sindan.org.br/mercado/ (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Braga, F.R.; Ferraz, C.M.; da Silva, E.N.; de Araújo, J.V. Efficiency of the Bioverm® (Duddingtonia Flagrans) Fungal Formulation to Control in Vivo and in Vitro of Haemonchus Contortus and Strongyloides Papillosus in Sheep. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, P.J. Sustainable Nematode Parasite Control Strategies for Ruminant Livestock by Grazing Management and Biological Control. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2006, 126, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-de Gives, P.; López-Arellano, M.E.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L.; Olazarán-Jenkins, S.; Reyes-Guerrero, D.; Ramírez-Várgas, G.; Vega-Murillo, V.E. The Nematophagous Fungus Duddingtonia Flagrans Reduces the Gastrointestinal Parasitic Nematode Larvae Population in Faeces of Orally Treated Calves Maintained under Tropical Conditions—Dose/Response Assessment. Vet. Parasitol. 2018, 263, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J.V.d.; Fonseca, J.D.S.; Barbosa, B.B.; Valverde, H.A.; Santos, H.A.; Braga, F.R. The Role of Helminthophagous Fungi in the Biological Control of Human and Zoonotic Intestinal Helminths. Pathogens 2024, 13, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro Oliveira, I.; Vieira, Í.S.; de Carvalho, L.M.; Campos, A.K.; Freitas, S.G.; de Araujo, J.M.; Braga, F.R.; de Araújo, J.V. Reduction of Bovine Strongilides in Naturally Contaminated Pastures in the Southeast Region of Brazil. Exp. Parasitol. 2018, 194, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soder, K.J.; Holden, L.A. Use of Nematode-Trapping Fungi as a Biological Control in Grazing Livestock. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2005, 21, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, Í.S.; Oliveira, I.D.C.; Freitas, S.G.; Campos, A.K.; Araújo, J.V.D. Arthrobotrys Cladodes and Pochonia Chlamydosporia in the Biological Control of Nematodiosis in Extensive Bovine Production System. Parasitology 2020, 147, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.d.C.; Vieira, Í.S.; Freitas, S.G.; Campos, A.K.; Araújo, J.V. Monacrosporium Sinense and Pochonia Chlamydosporia for the Biological Control of Bovine Infective Larvae in Brachiaria Brizantha Pasture. Biol. Control 2022, 171, 104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, J.V. Advances in the Control of the Helminthosis in Domestic Animals. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, F.R.; De Araújo, J.V. Nematophagous Fungi for Biological Control of Gastrointestinal Nematodes in Domestic Animals. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-de Gives, P.; Braga, F.R.; de Araújo, J.V. Nematophagous Fungi, an Extraordinary Tool for Controlling Ruminant Parasitic Nematodes and Other Biotechnological Applications. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2022, 32, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J.V.; Braga, F.R.; Mendoza-de-Gives, P.; Paz-Silva, A.; Vilela, V.L.R. Recent Advances in the Control of Helminths of Domestic Animals by Helminthophagous Fungi. Parasitologia 2021, 1, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Fonseca, J.; Altoé, L.S.C.; de Carvalho, L.M.; de Freitas Soares, F.E.; Braga, F.R.; de Araújo, J.V. Nematophagous Fungus Pochonia Chlamydosporia to Control Parasitic Diseases in Animals. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 3859–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, J.D.S.; Ferreira, V.M.; de Freitas, S.G.; Vieira, Í.S.; de Araújo, J.V. Efficacy of a Fungal Formulation with the Nematophagous Fungus Pochonia Chlamydosporia in the Biological Control of Bovine Nematodiosis. Pathogens 2022, 11, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves do Carmo, T.; Oliveira Mena, M.; de Almeida Cipriano, I.; Mascoli de Favare, G.; Jabismar Guelpa, G.; da Costa Pinto, S.; Francisco Talamini do Amarante, A.; Víctor de Araújo, J.; Velludo Gomes de Soutello, R. Biological Control of Gastrointestinal Nematodes in Horses Fed with Grass in Association with Nematophagus Fungi Duddingtonia Flagrans and Pochonia Chlamydosporia. Biol. Control 2023, 182, 105219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, J.M.; de Araújo, J.V.; Braga, F.R.; Carvalho, R.O.; Ferreira, S.R. Activity of the Nematophagous Fungi Pochonia Chlamydosporia, Duddingtonia Flagrans and Monacrosporium Thaumasium on Egg Capsules of Dipylidium Caninum. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 166, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.M.; Whitlock, H.V. A New Technique for Counting Nematode Eggs in Sheep Faeces. J. Counc. Sci. Ind. Res. 1939, 12, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, S.; Zegbi, S.; Sagües, F.; Iglesias, L.; Guerrero, I.; Saumell, C. Trapping Behaviour of Duddingtonia Flagrans against Gastrointestinal Nematodes of Cattle under Year-Round Grazing Conditions. Pathogens 2023, 12, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Lv, J.; Jiang, L.; Fan, Z.; Hao, L.; Li, Z.; Ma, C.; Wang, R.; Luo, H. In Vitro Ovicidal Studies on Egg-Parasitic Fungus Pochonia Chlamydosporia and Safety Tests on Mice. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1505824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, W.R.; Stone, W.M.; Swanson, L.E. A New Laboratory and Field Diagnostic Test for Fluke Ova in Feces. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1954, 124, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Raynaud, J.P.; Gruner, L. Feasibility of Herbage Sampling in Large Extensive Pastures and Availability of Cattle Nematode Infective Larvae in Mountain Pastures. Vet. Parasitol. 1982, 10, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, R.K. The Differentiation of the Infective Larvae of Some Common Nematode Parasites of Cattle. Aust. J. Zool 1952, 1, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. PORTARIA SDA MAPA No 48 DE 12 05 1997. Ministério Da Agricultura e Pecuária. Available online: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/insumos-agropecuarios/insumos-pecuarios/produtos-veterinarios/legislacao-1/portaria/portaria-sda-mapa-no-48-de-12-05-1997.pdf/view (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Osterman-Lind, E.; Hedberg Alm, Y.; Hassler, H.; Wilderoth, H.; Thorolfson, H.; Tydén, E. Evaluation of Strategies to Reduce Equine Strongyle Infective Larvae on Pasture and Study of Larval Migration and Overwintering in a Nordic Climate. Animals 2022, 12, 3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, F.; Greer, A.W.; Coles, G.C.; Cringoli, G.; Papadopoulos, E.; Cabaret, J.; Berrag, B.; Varady, M.; Van Wyk, J.A.; Thomas, E.; et al. The Role of Targeted Selective Treatments in the Development of Refugia-Based Approaches to the Control of Gastrointestinal Nematodes of Small Ruminants. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 164, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilotto, F.; Fusé, L.A.; Sagües, M.F.; Iglesias, L.E.; Fernández, A.S.; Zegbi, S.; Guerrero, I.; Saumell, C.A. Predatory Effect of Duddingtonia Flagrans on Infective Larvae of Gastro-Intestinal Parasites under Sunny and Shaded Conditions. Exp. Parasitol. 2018, 193, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckler, R.P.; Borges, F. Climate Variations and the Environmental Population of Gastrointestinal Nematodes of Ruminants. Nematoda 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, D.; Gong, J.; Zhang, Y. Individual and Combined Application of Nematophagous Fungi as Biological Control Agents against Gastrointestinal Nematodes in Domestic Animals. Pathogens 2022, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.A.; Roque, F.L.; Álvares, F.B.V.; da Silva, A.L.P.; de Lima, E.F.; da Silva Filho, G.M.; Feitosa, T.F.; de Araújo, J.V.; Braga, F.R.; Vilela, V.L.R. Efficacy of a Commercial Fungal Formulation Containing Duddingtonia Flagrans (Bioverm®) for Controlling Bovine Gastrointestinal Nematodes. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária 2021, 30, e026620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Acosta, J.F.J.; Hoste, H. Alternative or Improved Methods to Limit Gastro-Intestinal Parasitism in Grazing Sheep and Goats. Small Rumin. Res. 2008, 77, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønvold, J.; Henriksen, S.A.; Larsen, M.; Nansen, P.; Wolstrup, J. Biological Control. Aspects of Biological Control—with Special Reference to Arthropods, Protozoans and Helminths of Domesticated Animals. Vet. Parasitol. 1996, 64, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzatti, A.; Santos, C.P.; Fernandes, M.A.M.; Yoshitani, U.Y.; Sprenger, L.K.; Molento, M.B. Duddingtonia Flagrans No Controle de Nematoides Gastrintestinais de Equinos Em Fases de Vida Livre. Arquivo Brasileiro de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia 2017, 69, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayupe, T.d.H. Arthrobotrys Cladodes Var Macroides e Pochonia Chlamydosporia Como Controladores Biológicos de Nematóides Parasitos Gastrintestinais de Equinos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Llorca, L.V.; Olivares-Bernabeu, C.; Salinas, J.; Jansson, H.B.; Kolattukudy, P.E. Pre-Penetration Events in Fungal Parasitism of Nematode Eggs. Mycol. Res. 2002, 106, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, R.A.; da Rocha, G.P.; Bricarello, P.A.; Amarante, A.F.T. Recovery of Trichostrongylus colubriformis infective larvae from three grass species contaminated in summer. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária 2008, 17, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmão de Quadros, D.; da Silva Sobrinho, A.G.; Rodrigues, L.R.d.A.; de Oliveira, G.P.; Xavier, C.P.; Andrade, A.P. Effect of Three Species of Forage Grasses on Pasture Structure and Vertical Distribution of Infective Larvae L3 of Gastrointestinal Nematodes of Sheep. Ciências Animais Brasileiras 2012, 13, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, J.; Morgan, E.R. The Influence of Water on the Migration of Infective Trichostrongyloid Larvae onto Grass. Parasitology 2011, 138, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vidal, M.L.B.; Fonseca, J.d.S.; Vieira, Í.S.; Altoé, L.S.C.; Carvalho, L.M.d.; Rodrigues, W.N.; Martins, I.V.F.; Araújo, J.V.d. Interaction Between Duddingtonia flagrans and Pochonia chlamydosporia for the Biological Control of Bovine Gastrointestinal Nematodes. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010085

Vidal MLB, Fonseca JdS, Vieira ÍS, Altoé LSC, Carvalho LMd, Rodrigues WN, Martins IVF, Araújo JVd. Interaction Between Duddingtonia flagrans and Pochonia chlamydosporia for the Biological Control of Bovine Gastrointestinal Nematodes. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010085

Chicago/Turabian StyleVidal, Maria Larissa Bitencourt, Júlia dos Santos Fonseca, Ítalo Stoupa Vieira, Lorena Souza Castro Altoé, Lorendane Millena de Carvalho, Wagner Nunes Rodrigues, Isabella Vilhena Freire Martins, and Jackson Victor de Araújo. 2026. "Interaction Between Duddingtonia flagrans and Pochonia chlamydosporia for the Biological Control of Bovine Gastrointestinal Nematodes" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010085

APA StyleVidal, M. L. B., Fonseca, J. d. S., Vieira, Í. S., Altoé, L. S. C., Carvalho, L. M. d., Rodrigues, W. N., Martins, I. V. F., & Araújo, J. V. d. (2026). Interaction Between Duddingtonia flagrans and Pochonia chlamydosporia for the Biological Control of Bovine Gastrointestinal Nematodes. Microorganisms, 14(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010085