Seasonal Dynamics of Foliar Fungi Associated with the Invasive Plant Ageratina adenophora

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Research Site

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Isolation and Culture of Fungi and DNA Extraction

2.4. Fungal DNA Extraction Without Cultivation

2.5. Sequence Processing

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

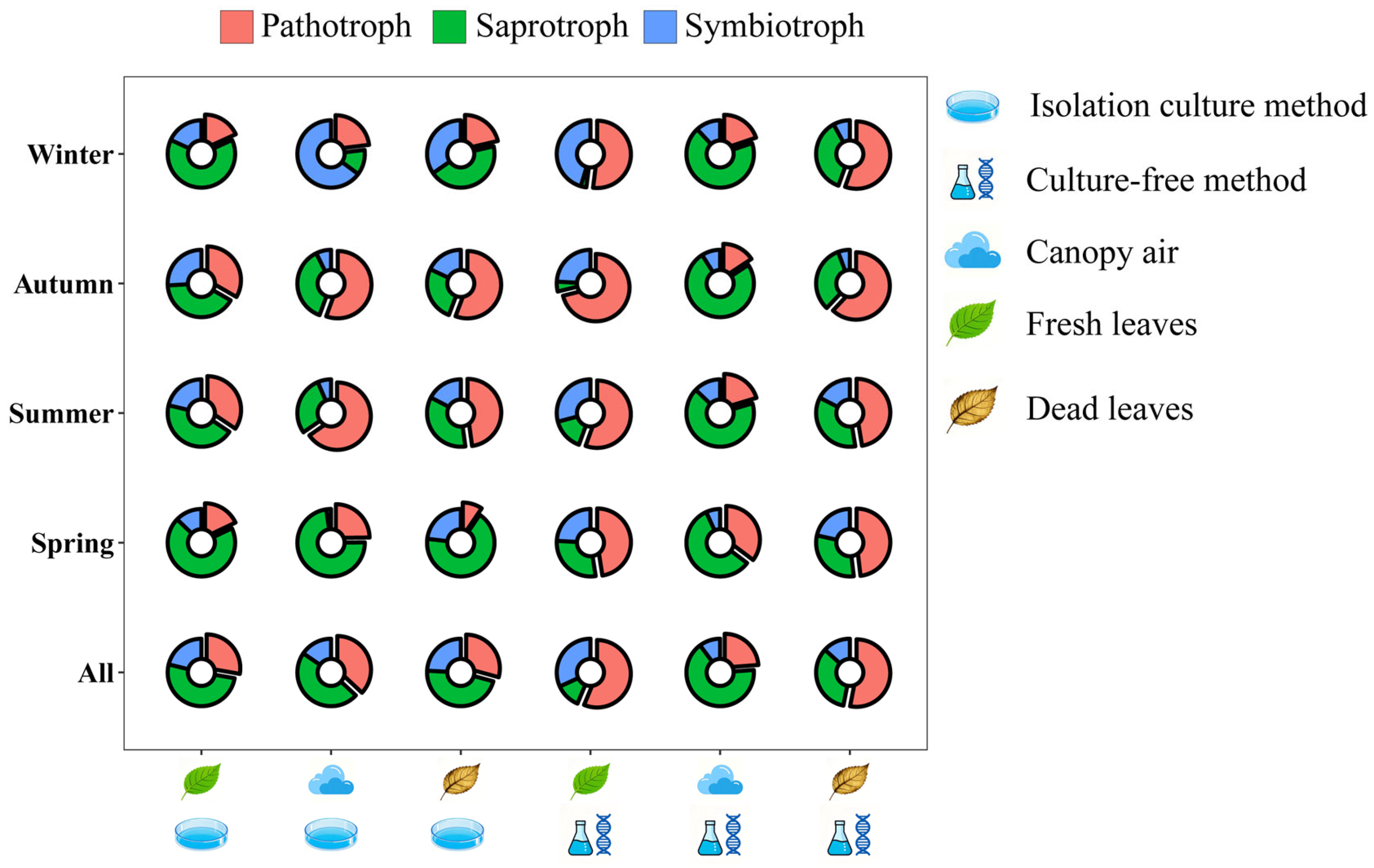

3.1. Predicted Trophic Mode of Fungi Associated with A. adenophora

3.2. Fungal Community Structure Associated with A. adenophora

3.3. Diversity of Fungal Communities Associated with A. adenophora

3.4. Effects of Environmental Factors on Fungal Communities Associated with A. Adenophora

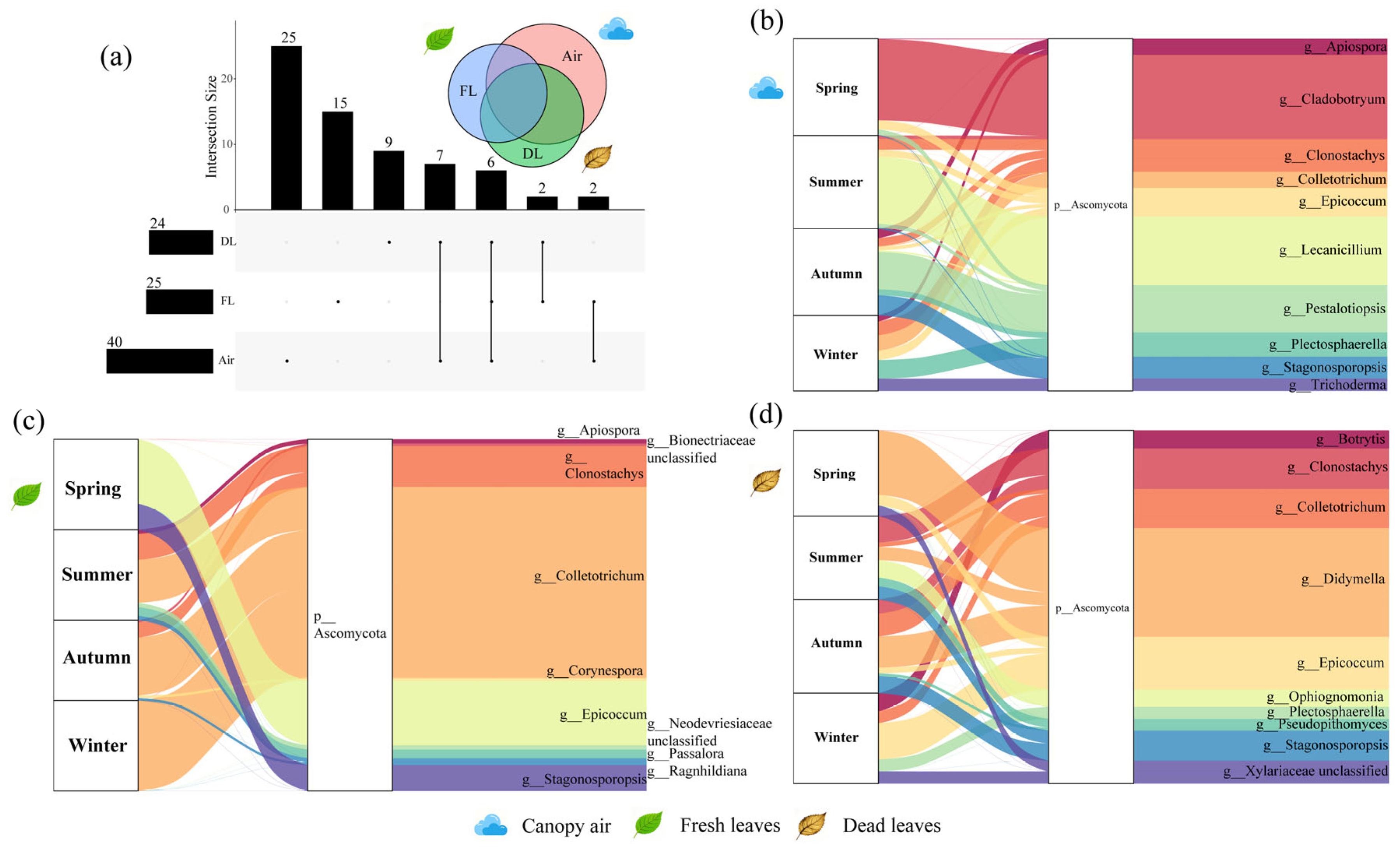

3.5. Potential Modes of Transmission of Pathogenic Fungi Associated with Fresh Leaves of A. adenophora

4. Discussion

4.1. The Potential of the Healthy Leaves of the Invasive Plant A. adenophora as a Reservoir of Pathogenic Fungi

4.2. Seasonal Dynamics of Pathogenic Fungal Community Composition and Diversity

4.3. Environmental Factors Accounting for Community Dynamics

4.4. Potential Transmission Patterns of Pathogenic Fungi

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patejuk, K.; Najberek, K.; Pacek, P.; Bocianowski, J.; Pusz, W. Fungal Phytopathogens: Their Role in the Spread and Management of Invasive Alien Plants. Forests 2024, 15, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; White, A.; Boots, M. Invading with biological weapons: The importance of disease-mediated invasions. Funct. Ecol. 2012, 26, 1249–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, R.M.; Crawley, M.J. Exotic plant invasions and the enemy release hypothesis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2002, 17, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.E.; Power, A.G. Release of invasive plants from fungal and viral pathogens. Nature 2003, 421, 625–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.-Z.; Liu, M.-C.; Feng, Y.-L.; Wang, D.; Feng, W.-W.; Clay, K.; Durden, L.A.; Lu, X.-R.; Wang, S.; Wei, X.-L.; et al. Release from below- and aboveground natural enemies contributes to invasion success of a temperate invader. Plant Soil 2020, 452, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.E.; Blumenthal, D.; Jarošík, V.; Puckett, E.E.; Pyšek, P. Controls on pathogen species richness in plants’ introduced and native ranges: Roles of residence time, range size and host traits. Ecol. Lett. 2010, 13, 1525–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppinga, M.B.; Rietkerk, M.; Dekker, S.C.; De Ruiter, P.C.; Van der Putten, W.H.; Van der Putten, W.H. Accumulation of local pathogens: A new hypothesis to explain exotic plant invasions. Oikos 2006, 114, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, W.J.; Meyerson, L.A.; Flick, A.J.; Cronin, J.T. Intraspecific variation in indirect plant–soil feedbacks influences a wetland plant invasion. Ecology 2018, 99, 1430–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, R.A.; Ramsey, P.W.; Lekberg, Y. Do native and invasive plants differ in their interactions with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi? A meta-analysis. J. Ecol. 2015, 103, 1547–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, S.; Callaway, R.M. Exotic invasive plant accumulates native soil pathogens which inhibit native plants. J. Ecol. 2008, 96, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Peña, E.; de Clercq, N.; Bonte, D.; Roiloa, S.; Rodríguez-Echeverría, S.; Freitas, H. Plant-soil feedback as a mechanism of invasion by Carpobrotus edulis. Biol. Invasions 2010, 12, 3637–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Sun, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhai, X.; Callaway, R.M.; Wan, J.; Flory, S.L.; Huang, W.; Ding, J. Trade-offs in non-native plant herbivore defences enhance performance. Ecol. Lett. 2023, 26, 1584–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Yang, S.; Manan, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, G.; He, W.; Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, B. Increased nitrogen deposition may facilitate an invasive plant species through interfering plant–pathogen interactions. J. Ecol. 2025, 113, 3345–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Manan, A.; Yang, S.; Zhu, G.; Wang, Y.; Dai, Z.; Vrieling, K.; Li, B. Heavy metal pollution enhances pathogen resistance of an invasive plant species over its native congener. Funct. Ecol. 2025, 39, 1096–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Ding, P.; Song, X.E.; Yuan, X.; Yang, X. Stronger mutualistic interactions with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi help Asteraceae invaders outcompete the phylogenetically related natives. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, B.; Ding, J.; Huang, W.; Siemann, E. Escaping enemies enhances invader mutualisms: Role of metabolites. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2025, 40, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xiong, C.; Wei, Z.; Chen, Q.; Ma, B.; Zhou, S.; Tan, J.; Zhang, L.; Cui, H.; Duan, G. Impacts of global change on the phyllosphere microbiome. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1977–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, I.; War, A.F.; Rafiq, I.; Reshi, Z.A.; Rashid, I.; Shouche, Y.S. Phyllosphere microbiome: Diversity and functions. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 254, 126888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, R.; Laforest-Lapointe, I. Plant-microbe interactions in the phyllosphere: Facing challenges of the anthropocene. ISME J. 2022, 16, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allsup, C.M.; George, I.; Lankau, R.A. Shifting microbial communities can enhance tree tolerance to changing climates. Science 2023, 380, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacher, C.; Hampe, A.; Porté, A.J.; Sauer, U.; Compant, S.; Morris, C.E. The Phyllosphere: Microbial Jungle at the Plant–Climate Interface. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2016, 47, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.M.; Chitrakar, R.; Obulareddy, N.; Panchal, S.; Williams, P.; Melotto, M. Molecular battles between plant and pathogenic bacteria in the phyllosphere. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2010, 43, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, M.; Bulgheresi, S. A complex journey: Transmission of microbial symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roussin-Léveillée, C.; Rossi, C.A.M.; Castroverde, C.D.M.; Moffett, P. The plant disease triangle facing climate change: A molecular perspective. Trends Plant Sci. 2024, 29, 895–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pangga, I.B.; Hanan, J.; Chakraborty, S. Pathogen dynamics in a crop canopy and their evolution under changing climate. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, E.A.; Carson, W.P. The Ecology and Natural History of Foliar Bacteria with a Focus on Tropical Forests and Agroecosystems. Bot. Rev. 2015, 81, 105–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.E.; Herre, E.A. Canopy cover and leaf age affect colonization by tropical fungal endophytes: Ecological pattern and process in Theobroma cacao (Malvaceae). Mycologia 2003, 95, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.R.; Finlay, R.D.; Stenlid, J.; Vasaitis, R.; Menkis, A. Growing evidence for facultative biotrophy in saprotrophic fungi: Data from microcosm tests with 201 species of wood-decay basidiomycetes. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryanarayanan, T.S. Endophyte research: Going beyond isolation and metabolite documentation. Fungal Ecol. 2013, 6, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szink, I.; Davis, E.L.; Ricks, K.D.; Koide, R.T. New evidence for broad trophic status of leaf endophytic fungi of Quercus gambelii. Fungal Ecol. 2016, 22, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osono, T. Role of phyllosphere fungi of forest trees in the development of decomposer fungal communities and decomposition processes of leaf litter. Can. J. Microbiol. 2006, 52, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niture, S.K.; Pant, A. Production of cell wall-degrading enzymes by a pH tolerant estuarine fungal isolate Fusarium moniliforme NCIM1276 in different culture conditions. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 23, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, B.W.G.; Jackson, C.R. Seasonal Patterns Contribute More Towards Phyllosphere Bacterial Community Structure than Short-Term Perturbations. Microb. Ecol. 2021, 81, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, M.M.; Bebber, D.P. Climate change and plant pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2022, 70, 102233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussin-Léveillée, C.; Mackey, D.; Ekanayake, G.; Gohmann, R.; Moffett, P. Extracellular niche establishment by plant pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, X.; Nomura, K.; Aung, K.; Velásquez, A.C.; Yao, J.; Boutrot, F.; Chang, J.H.; Zipfel, C.; He, S.Y. Bacteria establish an aqueous living space in plants crucial for virulence. Nature 2016, 539, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faticov, M.; Abdelfattah, A.; Roslin, T.; Vacher, C.; Hambäck, P.; Blanchet, F.G.; Lindahl, B.D.; Tack, A.J.M. Climate warming dominates over plant genotype in shaping the seasonal trajectory of foliar fungal communities on oak. New Phytol. 2021, 231, 1770–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Hu, H.-W.; Yan, Z.; Li, C.-Y.; Nguyen, B.T.; Zhu, Y.; He, J. Precipitation increases the abundance of fungal plant pathogens in Eucalyptus phyllosphere. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 7688–7700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, F.; Cazzato, S.; Walder, F.; Vogelgsang, S.; Bender, S.F.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Humidity and high temperature are important for predicting fungal disease outbreaks worldwide. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1553–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almario, J.; Mahmoudi, M.; Kroll, S.; Agler, M.; Placzek, A.; Mari, A.; Kemen, E. The Leaf Microbiome of Arabidopsis Displays Reproducible Dynamics and Patterns throughout the Growing Season. mBio 2022, 13, e02825-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma Poudel, A.; Babu Shrestha, B.; Kumar Jha, P.; Bahadur Baniya, C.; Muniappan, R. Stem galling of Ageratina adenophora (Asterales: Asteraceae) by a biocontrol agent Procecidochares utilis (Diptera: Tephritidae) is elevation dependent in central Nepal. Biocontrol. Sci. Techn. 2020, 30, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y.-Z. Invasion dynamics and potential spread of the invasive alien plant species Ageratina adenophora (Asteraceae) in China. Divers. Distrib. 2006, 12, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, D.-Z.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Guo, J.; Zhang, H.-B. Geographical and Temporal Changes of Foliar Fungal Endophytes Associated with the Invasive Plant Ageratina adenophora. Microb. Ecol. 2014, 67, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, J.; Zeng, T.; Miao, Y.; Mei, L.; Yao, G.; Fang, K.; Dong, X.; Sha, T.; Yang, M.; et al. Quantifying the sharing of foliar fungal pathogens by the invasive plant Ageratina adenophora and its neighbours. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 1493–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, A.S.; Jha, P.K.; Shrestha, B.B.; Muniappan, R. Biology and management of the invasive weed Ageratina adenophora (Asteraceae): Current state of knowledge and future research needs. Weed Res. 2019, 59, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-X.; Dong, X.-F.; Yang, A.-L.; Zhang, H.-B. Diversity and pathogenicity of Alternaria species associated with the invasive plant Ageratina adenophora and local plants. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yang, A.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Genetic Evidence for Colletotrichum gloeosporioides Transmission Between the Invasive Plant Ageratina adenophora and Co-occurring Neighbor Plants. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 2192–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Yang, A.L.; Li, Y.X.; Zhang, H.B. Virulence and Host Range of Fungi Associated With the Invasive Plant Ageratina adenophora. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 857796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovaskainen, O.; Abrego, N.; Somervuo, P.; Palorinne, I.; Hardwick, B.; Pitkänen, J.-M.; Andrew, N.R.; Niklaus, P.A.; Schmidt, N.M.; Seibold, S.; et al. Monitoring Fungal Communities With the Global Spore Sampling Project. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 7, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.E.; Lutzoni, F. Diversity and host range of foliar fungal endophytes: Are tropical leaves biodiversity hotspots? Ecology 2007, 88, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolan, M.E.; Pukkila, P.J. Inheritance of DNA methylation in Coprinus cinereus. Mol. Cell Biol. 1986, 6, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.D.; Lee, S.B.; Taylor, J.W. Analysis of phylogenetic relationships by amplification and direct sequencing of ribosomal RNA genes. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, I.; Friberg, H.; Steinberg, C.; Persson, P. Fungicide Effects on Fungal Community Composition in the Wheat Phyllosphere. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A User-Friendly Biological Sequence Alignment Editor and Analysis Program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, S.; Liu, Y.-X. Wekemo Bioincloud: A user-friendly platform for meta-omics data analyses. iMeta 2024, 3, e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, F.; Han, F.; Ge, C.; Mao, W.; Chen, L.; Hu, H.; Chen, G.; Lang, Q.; Fang, C. OmicStudio: A composable bioinformatics cloud platform with real-time feedback that can generate high-quality graphs for publication. iMeta 2023, 2, e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Song, Z.; Bates, S.T.; Branco, S.; Tedersoo, L.; Menke, J.; Schilling, J.S.; Kennedy, P.G. FUNGuild: An open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newfeld, J.; Ujimatsu, R.; Hiruma, K. Uncovering the Host Range-Lifestyle Relationship in the Endophytic and Anthracnose Pathogenic Genus Colletotrichum. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Silva, D.D.; Crous, P.W.; Ades, P.K.; Hyde, K.D.; Taylor, P.W.J. Life styles of Colletotrichum species and implications for plant biosecurity. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2017, 31, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Li, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, H. Role of the Foliar Endophyte Colletotrichum in the Resistance of Invasive Ageratina adenophora to Disease and Abiotic Stress. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.H.; Li, J.X.; Qi, Y.; Liu, D.H.; Miao, Y.H. First Report of Leaf Spot on White Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium) Caused by Epicoccum sorghinum in Hubei Province, China. Plant Dis. 2020, 105, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguiam, J.D.; Evallo, E.; Balendres, M.A. Epicoccum species: Ubiquitous plant pathogens and effective biological control agents. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 159, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Zhang, X.; Xu, D.; Zhang, B.; Lai, D.; Zhou, L. Metabolites from Clonostachys Fungi and Their Biological Activities. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Chen, L.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Z.-P.; Dong, X.-F.; Zhang, H.-B. Plant–soil–foliage feedbacks on seed germination and seedling growth of the invasive plant Ageratina adenophora. Proc. R. Soc. B 2019, 286, 20191520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, M.; Zare, R.; Jafary, H. Toxicocladosporium crousianum and T. eucalyptorum, two new foliar fungi associated with Eucalyptus trees. Mycol. Prog. 2022, 21, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, J.D.P.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Paiva, L.M.; Silva, G.A.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Souza-Motta, C.M.; Crous, P.W. New endophytic Toxicocladosporium species from cacti in Brazil, and description of Neocladosporium gen. nov. IMA Fungus 2017, 8, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotedar, R.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Kolecka, A.; Zeyara, A.; Al Malki, A.; Al Shammari, H.; Al Marri, M.; Kaul, R.; Boekhout, T. Toxicocladosporium aquimarinum sp. nov. and Toxicocladosporium qatarense sp. nov., isolated from marine waters of the Arabian Gulf surrounding Qatar. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 2992–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinkevičienė, J.; Sinkevičiūtė, A.; Česonienė, L.; Daubaras, R. Fungi Present in the Clones and Cultivars of European Cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccos) Grown in Lithuania. Plants 2023, 12, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, T.Y.K.; Silva, T.C.; Moreira, S.I.; Christiano, F.S.; Gasparoto, M.C.G.; Fraaije, B.A.; Ceresini, P.C. Evidence of Resistance to QoI Fungicides in Contemporary Populations of Mycosphaerella fijiensis, M. musicola and M. thailandica from Banana Plantations in Southeastern Brazil. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H.; Yang, Y.; Song, W.; Hsiang, T.; Liu, L.; Gao, J. Advances in Current Research of Fungi in Genus Didymella. J. Fungal Res. 2024, 22, 207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Miao, Y.; Fang, K.; Chen, L.; Yang, Z.; Dong, X.; Zhang, H. Diversity of the endophytic and rhizosphere soil fungi of Ageratina adenophora. Ecol. Sci. 2019, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Agan, A.; Solheim, H.; Adamson, K.; Hietala, A.M.; Tedersoo, L.; Drenkhan, R. Seasonal Dynamics of Fungi Associated with Healthy and Diseased Pinus sylvestris Needles in Northern Europe. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumpponen, A.; Jones, K.L. Seasonally dynamic fungal communities in the Quercus macrocarpa phyllosphere differ between urban and nonurban environments. New Phytol. 2010, 186, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Jia, L.; Herrera-Balandrano, D.D.; Wang, S.; Laborda, P. Occurrence and Management of the Emerging Pathogen Epicoccum sorghinum. Plant Dis. 2024, 109, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhadauria, V.; Li, G.; Gao, X.; Laborda, P. Near-complete genome and infection transcriptomes of the maize leaf and sheath spot pathogen Epicoccum sorghinum. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cal, A.; Larena, I.; Liñán, M.; Torres, R.; Lamarca, N.; Usall, J.; Domenichini, P.; Bellini, A.; De Eribe, X.O.; Melgarejo, P. Population dynamics of Epicoccum nigrum, a biocontrol agent against brown rot in stone fruit. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 106, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearn, J.A.; Sutton, B.C.; Morley, N.J.; Gange, A.C. Species and organ specificity of fungal endophytes in herbaceous grassland plants. J. Ecol. 2012, 100, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Akutse, K.S.; Saqib, H.S.A.; Wu, X.; Yang, F.; Xia, X.; Wang, L.; Goettel, M.S.; You, M.; Gurr, G.M. Fungal Endophyte Communities of Crucifer Crops Are Seasonally Dynamic and Structured by Plant Identity, Plant Tissue and Environmental Factors. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Zhou, L.; Fang, Q.; Xiao, H.; Jin, D.; Liu, Y. Growth period and variety together drive the succession of phyllosphere microbial communities of grapevine. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 950, 175334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crucitti, D.; Sonnessa, M.; Carimi, F.; Caruso, T.; Pacifico, D. Endophytic microbiota diversity in the phyllosphere of Sicilian olive trees across growth phases and farming systems. Curr. Plant Biol. 2025, 43, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lan, G. Distinct spatiotemporal patterns between fungal alpha and beta diversity of soil–plant continuum in rubber tree. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 13, e0209724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyer, J.K.; Grunberg, R.L.; Wang, J.; Mitchell, C.E. Leaf age structures phyllosphere microbial communities in the field and greenhouse. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1429166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrego, N.; Furneaux, B.; Hardwick, B.; Somervuo, P.; Palorinne, I.; Aguilar-Trigueros, C.A.; Andrew, N.R.; Babiy, U.V.; Bao, T.; Bazzano, G.; et al. Airborne DNA reveals predictable spatial and seasonal dynamics of fungi. Nature 2024, 631, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma Ghimire, P.; Joshi, D.R.; Tripathee, L.; Chen, P.; Sajjad, W.; Kang, S. Seasonal taxonomic composition of microbial communal shaping the bioaerosols milieu of the urban city of Lanzhou. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, Y.; Skjøth, C.A.; Hertel, O.; Rasmussen, K.; Sigsgaard, T.; Gosewinkel, U. Airborne Cladosporium and Alternaria spore concentrations through 26 years in Copenhagen, Denmark. Aerobiologia 2020, 36, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, X.; Almeida, L.C.S.d.S.; Pecoraro, L. Environmental Factors Affecting Diversity, Structure, and Temporal Variation of Airborne Fungal Communities in a Research and Teaching Building of Tianjin University, China. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žilka, M.; Hrabovský, M.; Dušička, J.; Zahradníková, E.; Gahurová, D.; Ščevková, J. Comparative analysis of airborne fungal spore distribution in urban and rural environments of Slovakia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 63145–63160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, D.; Wurster, S.; Jenks, J.D.; Sati, H.; Gangneux, J.-P.; Egger, M.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Ford, N.P.; Chowdhary, A.; Sprute, R.; et al. Impact of climate change and natural disasters on fungal infections. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, e594–e605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingales, V.; Taroncher, M.; Martino, P.A.; Ruiz, M.-J.; Caloni, F. Climate Change and Effects on Molds and Mycotoxins. Toxins 2022, 14, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylor, D.E. Biophysical scaling and the passive dispersal of fungus spores: Relationship to integrated pest management strategies. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1999, 97, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, J.C.; Street, N.R.; Sjödin, A.; Lee, N.M.; Högberg, M.N.; Näsholm, T.; Hurry, V. Microbial community response to growing season and plant nutrient optimisation in a boreal Norway spruce forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 125, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, Y.S.; Ge, Z.; Buie, C.R. Bioaerosol generation by raindrops on soil. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, S.G.; Gilbert, G.S. Meteorological factors associated with abundance of airborne fungal spores over natural vegetation. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 162, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Rico, L.; Ogaya, R.; Jump, A.S.; Terradas, J. Summer season and long-term drought increase the richness of bacteria and fungi in the foliar phyllosphere of Quercus ilex in a mixed Mediterranean forest. Plant Biol. 2012, 14, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, M.; Bartha, L.; O’Hara, R.B.; Olson, M.S.; Otte, J.; Pfenninger, M.; Robertson, A.L.; Tiffin, P.; Schmitt, I. Relocation, high-latitude warming and host genetic identity shape the foliar fungal microbiome of poplars. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, J.P.; Fawcett, L.; Anthony, S.G.; Young, C. A Model for Sclerotinia sclerotiorum Infection and Disease Development in Lettuce, Based on the Effects of Temperature, Relative Humidity and Ascospore Density. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granke, L.L.; Hausbeck, M.K. Effects of Temperature, Humidity, and Wounding on Development of Phytophthora Rot of Cucumber Fruit. Plant Dis. 2010, 94, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, K.; Jiang, Y.; He, S.Y. The role of water in plant–microbe interactions. Plant J. 2018, 93, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnadi, N.E.; Carter, D.A. Climate change and the emergence of fungal pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, T.B.; Gostinčar, C.; Gunde-Cimerman, N.; Rodrigues, A. Genome mining for peptidases in heat-tolerant and mesophilic fungi and putative adaptations for thermostability. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogan, E.L.; Moser, G.; Müller, C.; Kämpfer, P.; Glaeser, S.P. Long-Term Warming Shifts the Composition of Bacterial Communities in the Phyllosphere of Galium album in a Permanent Grassland Field-Experiment. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, M.; Grolig, F.; Haueisen, J.; Imhof, S. Combining microtomy and confocal laser scanning microscopy for structural analyses of plant–fungus associations. Mycorrhiza 2014, 24, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Ling, N.; Dong, X.; Zhu, Y.; Shen, Q.; Guo, S. Thermographic visualization of leaf response in cucumber plants infected with the soil-borne pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 61, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Basu, S.; Kim, S.; Sorrells, M.; Beron-Vera, F.J.; Jung, S. Coherent spore dispersion via drop-leaf interaction. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadj8092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, D.; Barbetti, M.J.; MacLeod, W.J.; Salam, M.U.; Renton, M. Seasonal and Diurnal Patterns of Spore Release Can Significantly Affect the Proportion of Spores Expected to Undergo Long-Distance Dispersal. Microb. Ecol. 2012, 63, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, B.R.; Daugherty, M.P. Understanding the effects of multiple sources of seasonality on the risk of pathogen spread to vineyards: Vector pressure, natural infectivity, and host recovery. Plant Pathol. 2013, 62, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, T.E.; Derbyshire, M.C. The Evolutionary and Molecular Features of Broad Host-Range Necrotrophy in Plant Pathogenic Fungi. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 591733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, G.C.; Crous, P.W.; Carnegie, A.J.; Burgess, T.I.; Wingfield, M.J. Mycosphaerella and Teratosphaeria diseases of Eucalyptus; easily confused and with serious consequences. Fungal Divers. 2011, 50, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bosch, F.; Fraaije, B.A.; van den Berg, F.; Shaw, M.W. Evolutionary bi-stability in pathogen transmission mode. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 277, 1735–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehman, J.S.; Shaner, G. Genetic variation in latent period among isolates of Puccinia recondita f. sp. tritici on partially resistant wheat cultivars. Phytopathology 1996, 86, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melloy, P.; Hollaway, G.; Luck, J.O.; Norton, R.O.B.; Aitken, E.; Chakraborty, S. Production and fitness of Fusarium pseudograminearum inoculum at elevated carbon dioxide in FACE. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 3363–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohalem, D.S.; Nielsen, K.; Green, H.; Funck Jensen, D. Biocontrol agents efficiently inhibit sporulation of Botrytis aclada on necrotic leaf tips but spread to adjacent living tissue is not prevented. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 47, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suto, Y. Mycosphaerella chaenomelis sp. nov.: The teleomorph ofCercosporella sp., the causal fungus of frosty mildew inChaenomeles sinensis, and its role as the primary infection source. Mycoscience 1999, 40, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunali, B.; Obanor, F.; Erginbaş, G.; Westecott, R.A.; Nicol, J.; Chakraborty, S. Fitness of three Fusarium pathogens of wheat. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 81, 596–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, A.-L.; Chen, Y.-S.; Mei, L.; Guo, J.; Zhang, H.-B. Disease risk of the foliar endophyte Colletotrichum from invasive Ageratina adenophora to native plants and crops. Fungal Ecol. 2024, 72, 101386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Y.-X.; Yang, A.-L.; Jin, X.-H.; Liu, Z.-Q.; Wang, Y.-L.; Zhao, C.; Zeng, Z.-Y.; Geng, Y.-P.; Zhang, H.-B. Seasonal Dynamics of Foliar Fungi Associated with the Invasive Plant Ageratina adenophora. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010084

Li Y-X, Yang A-L, Jin X-H, Liu Z-Q, Wang Y-L, Zhao C, Zeng Z-Y, Geng Y-P, Zhang H-B. Seasonal Dynamics of Foliar Fungi Associated with the Invasive Plant Ageratina adenophora. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010084

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yu-Xuan, Ai-Ling Yang, Xiao-Han Jin, Zi-Qing Liu, Yong-Lan Wang, Chao Zhao, Zhao-Ying Zeng, Yu-Peng Geng, and Han-Bo Zhang. 2026. "Seasonal Dynamics of Foliar Fungi Associated with the Invasive Plant Ageratina adenophora" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010084

APA StyleLi, Y.-X., Yang, A.-L., Jin, X.-H., Liu, Z.-Q., Wang, Y.-L., Zhao, C., Zeng, Z.-Y., Geng, Y.-P., & Zhang, H.-B. (2026). Seasonal Dynamics of Foliar Fungi Associated with the Invasive Plant Ageratina adenophora. Microorganisms, 14(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010084