The Human Virome in Health and Its Remodeling During HIV Infection and Antiretroviral Therapy: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Composition of the Human Virome

3. Virome of Different Human Body Sites

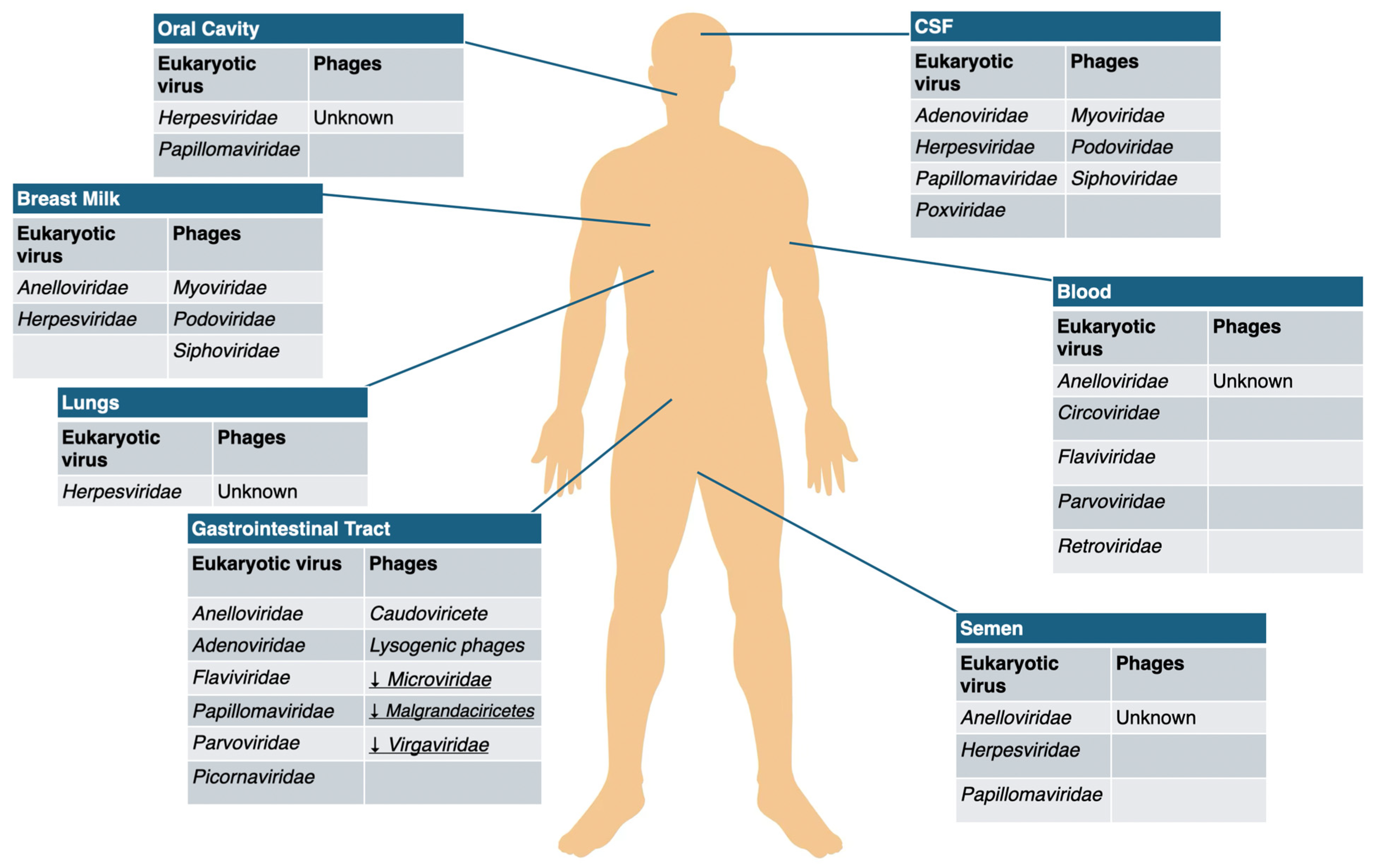

- Gut virome. The gastrointestinal tract is typically the site with the highest viral abundance, exhibiting considerable temporal stability within individuals but substantial variability between different people [28,29]. Analysis of virome sequencing from fecal samples indicates that bacteriophages constitute the majority of identifiable viral populations, accounting for over 90%, with most of them belonging to the order Caudovirales (Podoviridae and Siphoviridae) (dsDNA viruses) along with the spherical Microviridae (ssDNA viruses). Gut virome comprises also eukaryotic RNA viruses (e.g., rotaviruses, coronaviruses, sapoviruses and plant viruses) and eukaryotic DNA viruses (e.g., herpesviruses, adenoviruses and anelloviruses) [17].

- Blood virome. Studies conducted on the plasma virome show instead the predominance of eukaryotic viruses such as Anelloviridae, Herpesviridae and Picornaviridae and low abundance of phages (most prevalent were Caudovirales and Microviridae [30,31]. Some investigations, however, have reported higher levels of phage DNA in the blood of patients with cardiovascular disease and HIV compared to healthy individuals [29].

- Respiratory tract virome. Virome analyses of respiratory samples—including sputum, nasopharyngeal swabs, and bronchoalveolar lavage—indicate that the healthy human lung and respiratory tract can harbor extensive viral communities [32,33]. Research indicates that Anelloviridae, Redondaviridae, and Herpesviridae are the most prevalent viruses in samples from the human respiratory tract [34]. Bacteriophages detected in the lungs largely originate from the abundant bacterial communities of the mouth and upper respiratory tract, and their composition resembles that observed in the gut [17].

- Breast milk virome. Knowledge of the breast milk virome remains limited. In healthy U.S. women, most viruses detected in breast milk were bacteriophages belonging to the Myoviridae, Siphoviridae, and Podoviridae families, with eukaryotic viruses being rare [35]. However, only a small number of pathogenic viruses, such as HIV, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1), are known to be transmitted via breast milk [36]. These and other viral components may influence the infant gut microbiome and virome through immune modulation and inflammatory effects, with potential consequences for child health. Studies from Italy and the United States provide evidence for vertical transmission of the virome, as bacteriophage compositions in breast milk and infant stool from mother–infant pairs show significant similarity [37]. Consequently, changes in the breast milk virome could influence the initial development of both the infant virome and bacterial microbiome, potentially affecting long-term health outcomes [38].

- Other sites viromes. Little information is available on virome populations in other sites such as the nervous system, skin or urogenital system [39]. Anyway, even body sites largely isolated from typical microbial colonization, such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), exhibit low levels of viruses, including bacteriophages [17]. Siphoviridae and Myoviridae have been reported as predominant viral families in the CSF [40].

4. Approaches to Investigating the Virome and Its ‘Dark Matter’

5. HIV-Driven Alterations in the Human Virome

- Gut microbiome. The human gut ecosystem is shaped by the interaction among the bacteriome, virome, and phageome, which are in constant dialogue with the host. During HIV infection, immune alterations and bacterial dysbiosis disrupt this communication [3]. Phages regulate bacterial homeostasis through lytic, lysogenic, or pseudo-lysogenic cycles, and their overwhelming abundance positions the virome as a key modulator of the microbiota [49].

- Blood virome. Previous cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that HIV infection alters the plasma virome, primarily through the expansion of eukaryotic viruses [43]. While virome expansion associated with HIV occurs in both blood and gut, the specific eukaryotic viruses involved differ substantially, reflecting the distinct virome profiles across various tissues and organs [56]. Different from the main contribution of adenovirus to the gut virome expansion, plasma virome expansion caused by HIV infection is mainly driven by anelloviruses, which dominate the plasma virome [57].

- Genital Tract virome. Several studies also report high prevalence of Papillomaviridae in the oral and genital mucosa of individuals with severe immunodeficiency, and they are strongly implicated in the development of neoplastic lesions [1,58]. Recently, it has been described that the cervicovaginal virome of women living with HIV changes during ART, with anelloviruses abundance reduction during ART and concomitant with CD4+ increase [59].

- Respiratory tract virome. To date, published data on the lung virome in the context of HIV infection remain very limited. In a study involving a small cohort of PLWH, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) primarily revealed the presence of anelloviruses, followed by bacteriophages. Additionally, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), Retroviridae, and Parvoviridae were detected, with evidence of active replication in some cases, indicating ongoing viral activity [60].

6. The Virome in the Era of ART

7. Immunological and Clinical Implications

8. Future Perspectives and Conclusions

9. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stern, J.; Miller, G.; Li, X.; Saxena, D. Virome and bacteriome: Two sides of the same coin. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2019, 37, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Sun, J.; Wei, L.; Jiang, H.; Hu, C.; Yang, J.; Huang, Y.; Ruan, B.; Zhu, B. Altered gut microbiota correlate with different immune responses to HAART in HIV-infected individuals. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastav, K.; Nasser, H.; Ikeda, T.; Nema, V. Possible Crosstalk and Alterations in Gut Bacteriome and Virome in HIV-1 Infection and the Associated Comorbidities Related to Metabolic Disorder. Viruses 2025, 17, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, N.G.; Douek, D.C. Microbial translocation in HIV infection: Causes, consequences and treatment opportunities. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatt, N.R.; Chomont, N.; Douek, D.C.; Deeks, S.G. Immune activation and HIV persistence: Implications for curative approaches to HIV infection. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 254, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenchley, J.M.; Douek, D.C. Microbial translocation across the GI tract. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 30, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, S.M.; Frank, D.N.; Wilson, C.C. The gut microbiome and HIV-1 pathogenesis: A two-way street. AIDS 2016, 30, 2737–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazli, A.; Chan, O.; Dobson-Belaire, W.N.; Ouellet, M.; Tremblay, M.J.; Gray-Owen, S.D.; Arsenault, A.L.; Kaushic, C. Exposure to HIV-1 directly impairs mucosal epithelial barrier integrity allowing microbial translocation. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Tato, C.M.; Joyce-Shaikh, B.; Gulen, M.F.; Cayatte, C.; Chen, Y.; Blumenschein, W.M.; Judo, M.; Ayanoglu, G.; McClanahan, T.K.; et al. Interleukin-23-Independent IL-17 Production Regulates Intestinal Epithelial Permeability. Immunity 2015, 43, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: A collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV 2017, 4, e349–e356. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarrín, I.; Rava, M.; Del Romero Raposo, J.; Rivero, A.; Del Romero Guerrero, J.; De Lagarde, M.; Martínez Sanz, J.; Navarro, G.; Dalmau, D.; Blanco, J.R.; et al. Life expectancy of people with HIV on antiretroviral therapy in Spain. AIDS 2024, 38, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, P.W.; Lee, S.A.; Siedner, M.J. Immunologic Biomarkers, Morbidity, and Mortality in Treated HIV Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214 (Suppl. S2), S44–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.; Cao, L.; Li, Y.; Wan, Z.; Kane, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, C. Short-term antiretroviral therapy may not correct the dysregulations of plasma virome and cytokines induced by HIV-1 infection. Virulence 2025, 16, 2467168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathakumari, R.H.; Vajravelu, L.K.; Gopinathan, A.; Vimala, P.B.; Panneerselvam, V.; Ravi, S.S.S.; Thulukanam, J. The gut virome and human health: From diversity to personalized medicine. Eng. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, K.; Kanwar, R.; Ali, S.; Uddin, S.; Izza, I.; Ahmad, I.; Alzahrani, K.J.; Qadeer, A.; Chu, C.T.; Chen, C.C. Gut Virome and Aging: Phage-Driven Microbial Stability and Immune Modulation. Aging Dis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carding, S.R.; Davis, N.; Hoyles, L. Review article: The human intestinal virome in health and disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 800–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Bushman, F.D. The human virome: Assembly, composition and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecuit, M.; Eloit, M. The human virome: New tools and concepts. Trends Microbiol. 2013, 21, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Iwasa, Y.; Hijikata, M.; Mishiro, S. Identification of a new human DNA virus (TTV-like mini virus, TLMV) intermediately related to TT virus and chicken anemia virus. Arch. Virol. 2000, 145, 979–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spandole, S.; Cimponeriu, D.; Berca, L.M.; Mihăescu, G. Human anelloviruses: An update of molecular, epidemiological and clinical aspects. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, G.; Conrad, M.A.; Kelsen, J.R.; Kessler, L.R.; Breton, J.; Albenberg, L.G.; Marakos, S.; Galgano, A.; Devas, N.; Erlichman, J.; et al. Dynamics of the Stool Virome in Very Early-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2020, 14, 1600–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.C.; Chehoud, C.; Bittinger, K.; Bailey, A.; Diamond, J.M.; Cantu, E.; Haas, A.R.; Abbas, A.; Frye, L.; Christie, J.D.; et al. Viral metagenomics reveal blooms of anelloviruses in the respiratory tract of lung transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2015, 15, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spezia, P.G.; Macera, L.; Mazzetti, P.; Curcio, M.; Biagini, C.; Sciandra, I.; Turriziani, O.; Lai, M.; Antonelli, G.; Pistello, M.; et al. Redondovirus DNA in human respiratory samples. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 131, 104586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.M.; Handley, S.A.; Baldridge, M.T.; Droit, L.; Liu, C.Y.; Keller, B.C.; Kambal, A.; Monaco, C.L.; Zhao, G.; Fleshner, P.; et al. Disease-specific alterations in the enteric virome in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell 2015, 160, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chio, C.C.; Chien, J.C.; Chan, H.W.; Huang, H.I. Overview of the Trending Enteric Viruses and Their Pathogenesis in Intestinal Epithelial Cell Infection. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duerkop, B.A.; Hooper, L.V. Resident viruses and their interactions with the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Caler, L.; Colombini-Hatch, S.; Glynn, S.; Srinivas, P. Research on the human virome: Where are we and what is next. Microbiome 2016, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkoporov, A.N.; Clooney, A.G.; Sutton, T.D.S.; Ryan, F.J.; Daly, K.M.; Nolan, J.A.; McDonnell, S.A.; Khokhlova, E.V.; Draper, L.A.; Forde, A.; et al. The Human Gut Virome Is Highly Diverse, Stable, and Individual Specific. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 527–541.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascovan, N.; Duraisamy, R.; Desnues, C. Metagenomics and the Human Virome in Asymptomatic Individuals. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 70, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebriá-Mendoza, M.; Bracho, M.A.; Arbona, C.; Larrea, L.; Díaz, W.; Sanjuán, R.; Cuevas, J.M. Exploring the Diversity of the Human Blood Virome. Viruses 2021, 13, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Liu, B.; Cheng, M.; Dong, J.; Hu, Y.; Jin, Q.; Yang, F. An atlas of the blood virome in healthy individuals. Virus Res. 2023, 323, 199004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, K.M. The Virome of the Human Respiratory Tract. Clin. Chest Med. 2017, 38, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, B.N. Insights Into the Role of the Lung Virome During Respiratory Viral Infections. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 885341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, Y.; Cao, C.; Jiang, H.; Tang, R.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, W. Identification and characterization of novel CRESS-DNA viruses in the human respiratory tract. Virol. J. 2025, 22, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannaraj, P.S.; Ly, M.; Cerini, C.; Saavedra, M.; Aldrovandi, G.M.; Saboory, A.A.; Johnson, K.M.; Pride, D.T. Shared and Distinct Features of Human Milk and Infant Stool Viromes. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prendergast, A.J.; Goga, A.E.; Waitt, C.; Gessain, A.; Taylor, G.P.; Rollins, N.; Abrams, E.J.; Lyall, E.H.; de Perre, P.V. Transmission of CMV, HTLV-1, and HIV through breastmilk. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2019, 3, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duranti, S.; Lugli, G.A.; Mancabelli, L.; Armanini, F.; Turroni, F.; James, K.; Ferretti, P.; Gorfer, V.; Ferrario, C.; Milani, C.; et al. Maternal inheritance of bifidobacterial communities and bifidophages in infants through vertical transmission. Microbiome 2017, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautava, S. Early microbial contact, the breast milk microbiome and child health. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2016, 7, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popgeorgiev, N.; Temmam, S.; Raoult, D.; Desnues, C. Describing the silent human virome with an emphasis on giant viruses. Intervirology 2013, 56, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trunfio, M.; Scutari, R.; Fox, V.; Vuaran, E.; Dastgheyb, R.M.; Fini, V.; Granaglia, A.; Balbo, F.; Tortarolo, D.; Bonora, S.; et al. The cerebrospinal fluid virome in people with HIV: Links to neuroinflammation and cognition. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1704392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmer-Raynolds, L.D.; Sampson, T.R. The gut-brain axis goes viral. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayneris-Perxachs, J.; Castells-Nobau, A.; Arnoriaga-Rodríguez, M.; Garre-Olmo, J.; Puig, J.; Ramos, R.; Martínez-Hernández, F.; Burokas, A.; Coll, C.; Moreno-Navarrete, J.M.; et al. Caudovirales bacteriophages are associated with improved executive function and memory in flies, mice, and humans. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 340–356.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.K.; Leung, R.K.; Guo, H.X.; Wei, J.F.; Wang, J.H.; Kwong, K.T.; Lee, S.S.; Zhang, C.; Tsui, S.K. Detection and identification of plasma bacterial and viral elements in HIV/AIDS patients in comparison to healthy adults. Clin. Microbiol. Infect 2012, 18, 1126–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnifro, E.M.; Ashshi, A.M.; Cooper, R.J.; Klapper, P.E. Multiplex PCR: Optimization and application in diagnostic virology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.C.; Lee, T.T.; Chen, C.H.; Hsiao, H.Y.; Lin, Y.L.; Ho, M.S.; Yang, P.C.; Peck, K. Design of microarray probes for virus identification and detection of emerging viruses at the genus level. BMC Bioinform. 2006, 7, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pargin, E.; Roach, M.J.; Skye, A.; Papudeshi, B.; Inglis, L.K.; Mallawaarachchi, V.; Grigson, S.R.; Harker, C.; Edwards, R.A.; Giles, S.K. The human gut virome: Composition, colonization, interactions, and impacts on human health. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 963173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.H.; Lin, S.C.; Hsu, Y.H.; Chen, S.Y. The Human Virome: Viral Metagenomics, Relations with Human Diseases, and Therapeutic Applications. Viruses 2022, 14, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Bolduc, B.; Zayed, A.A.; Varsani, A.; Dominguez-Huerta, G.; Delmont, T.O.; Pratama, A.A.; Gazitúa, M.C.; Vik, D.; Sullivan, M.B.; et al. VirSorter2: A multi-classifier, expert-guided approach to detect diverse DNA and RNA viruses. Microbiome 2021, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, C.L.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Zhao, G.; Handley, S.A.; Ghebremichael, M.S.; Lim, E.S.; Lankowski, A.; Baldridge, M.T.; Wilen, C.B.; Flagg, M.; et al. Altered Virome and Bacterial Microbiome in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Associated Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’arc, M.; Furtado, C.; Siqueira, J.D.; Seuánez, H.N.; Ayouba, A.; Peeters, M.; Soares, M.A. Assessment of the gorilla gut virome in association with natural simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Retrovirology 2018, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handley, S.A.; Thackray, L.B.; Zhao, G.; Presti, R.; Miller, A.D.; Droit, L.; Abbink, P.; Maxfield, L.F.; Kambal, A.; Duan, E.; et al. Pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infection is associated with expansion of the enteric virome. Cell 2012, 151, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, S.A.; Desai, C.; Zhao, G.; Droit, L.; Monaco, C.L.; Schroeder, A.C.; Nkolola, J.P.; Norman, M.E.; Miller, A.D.; Wang, D.; et al. SIV Infection-Mediated Changes in Gastrointestinal Bacterial Microbiome and Virome Are Associated with Immunodeficiency and Prevented by Vaccination. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Song, T.Z.; Cao, L.; Zhang, H.D.; Ma, Y.; Tian, R.R.; Zheng, Y.T.; Zhang, C. Large expansion of plasma commensal viruses is associated with SIV pathogenesis in Macaca leonina. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadq1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sharma, S.; Tom, L.; Liao, Y.T.; Wu, V.C.H. Gut Phageome-An Insight into the Role and Impact of Gut Microbiome and Their Correlation with Mammal Health and Diseases. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villoslada-Blanco, P.; Pérez-Matute, P.; Íñiguez, M.; Recio-Fernández, E.; Jansen, D.; De Coninck, L.; Close, L.; Blanco-Navarrete, P.; Metola, L.; Ibarra, V.; et al. Impact of HIV infection and integrase strand transfer inhibitors-based treatment on the gut virome. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyöriä, L.; Pratas, D.; Toppinen, M.; Hedman, K.; Sajantila, A.; Perdomo, M.F. Unmasking the tissue-resident eukaryotic DNA virome in humans. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 3223–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Cao, L.; Ye, M.; Xu, R.; Chen, X.; Ma, Y.; Tian, R.R.; Liu, F.L.; Zhang, P.; Kuang, Y.Q.; et al. Plasma Virome Reveals Blooms and Transmission of Anellovirus in Intravenous Drug Users with HIV-1, HCV, and/or HBV Infections. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0144722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos Peña, D.E.; Pillet, S.; Grupioni Lourenço, A.; Pozzetto, B.; Bourlet, T.; Motta, A.C.F. Human immunodeficiency virus and oral microbiota: Mutual influence on the establishment of a viral gingival reservoir in individuals under antiretroviral therapy. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1364002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelin, E.A.; Mitchell, C.; Soria, J.; Rosa, A.; Ticona, E.; Coombs, R.W.; Frenkel, L.M.; Bull, M.E.; Lim, E.S. Longitudinal cervicovaginal bacteriome and virome alterations associate with discordant shedding and ART duration in women living with HIV in Peru. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigg, H.L., 3rd; Weinstock, G.M.; Knox, K.S. Lung microbiome in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Transl. Res. 2017, 179, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, E.; Nannini, G.; Sterrantino, G.; Kiros, S.T.; Di Pilato, V.; Coppi, M.; Baldi, S.; Niccolai, E.; Ricci, F.; Ramazzotti, M.; et al. Effects of viremia and CD4 recovery on gut “microbiome-immunity” axis in treatment-naïve HIV-1-infected patients undergoing antiretroviral therapy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, F.C.; Hardy, B.L.; Bishop-Lilly, K.A.; Frey, K.G.; Hamilton, T.; Whitney, J.B.; Lewis, M.G.; Merrell, D.S.; Mattapallil, J.J. Microbial Dysbiosis During Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Infection is Partially Reverted with Combination Anti-retroviral Therapy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukadida, C.; Peralta-Prado, A.; Chávez-Torres, M.; Romero-Mora, K.; Rincon-Rubio, A.; Ávila-Ríos, S.; Garrido-Rodríguez, D.; Reyes-Terán, G.; Pinto-Cardoso, S. Alterations of the gut microbiome in HIV infection highlight human anelloviruses as potential predictors of immune recovery. Microbiome 2024, 12, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Prado, E.; Simbaña-Rivera, K.; Gómez-Barreno, L.; Rubio-Neira, M.; Guaman, L.P.; Kyriakidis, N.C.; Muslin, C.; Jaramillo, A.M.G.; Barba-Ostria, C.; Cevallos-Robalino, D.; et al. Clinical, molecular, and epidemiological characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), a comprehensive literature review. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 98, 115094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imahashi, M.; Ode, H.; Kobayashi, A.; Nemoto, M.; Matsuda, M.; Hashiba, C.; Hamano, A.; Nakata, Y.; Mori, M.; Seko, K.; et al. Impact of long-term antiretroviral therapy on gut and oral microbiotas in HIV-1-infected patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolo, O.; Coulibaly, F.; Somboro, A.M.; Sun, S.; Diarra, M.; Maiga, A.; Bore, S.; Fofana, D.B.; Marcelin, A.G.; Diakite, B.; et al. The human gut microbiome and its metabolic pathway dynamics before and during HIV antiretroviral therapy. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0220524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocchi, J.; Ricci, V.; Albani, M.; Lanini, L.; Andreoli, E.; Macera, L.; Pistello, M.; Ceccherini-Nelli, L.; Bendinelli, M.; Maggi, F. Torquetenovirus DNA drives proinflammatory cytokines production and secretion by immune cells via toll-like receptor 9. Virology 2009, 394, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, C.; Wan, Z.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Jin, X.; Hao, P.; et al. HIV-1 Infection Alters the Viral Composition of Plasma in Men Who Have Sex with Men. mSphere 2021, 6, e00081-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarancon-Diez, L.; Carrasco, I.; Montes, L.; Falces-Romero, I.; Vazquez-Alejo, E.; Jiménez de Ory, S.; Dapena, M.; Iribarren, J.A.; Díez, C.; Ramos-Ruperto, L.; et al. Torque teno virus: A potential marker of immune reconstitution in youths with vertically acquired HIV. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, P.L.; Quintanares, G.H.R.; Langhans, B.; Heger, E.; Böhm, M.; Jensen, B.O.L.E.; Esser, S.; Lübke, N.; Fätkenheuer, G.; Lengauer, T.; et al. Torque Teno Virus Load Is Associated with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Stage and CD4+ Cell Count in People Living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus but Seems Unrelated to AIDS-Defining Events and Human Pegivirus Load. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 230, e437–e446, Erratum in J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 230, e1181.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, K.; Petrik, J. Progression towards AIDS leads to increased Torque teno virus and Torque teno minivirus titers in tissues of HIV infected individuals. J. Med. Virol. 2007, 79, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, L.; Jensen, B.O.; Walker, A.; Keitel-Anselmino, V.; di Cristanziano, V.; Böhm, M.; Knops, E.; Heger, E.; Kaiser, R.; de Luca, A.; et al. Torque Teno Virus plasma level as novel biomarker of retained immunocompetence in HIV-infected patients. Infection 2021, 49, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibayama, T.; Masuda, G.; Ajisawa, A.; Takahashi, M.; Nishizawa, T.; Tsuda, F.; Okamoto, H. Inverse relationship between the titre of TT virus DNA and the CD4 cell count in patients infected with HIV. AIDS 2001, 15, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Wünschmann, S.; Diekema, D.J.; Klinzman, D.; Patrick, K.D.; George, S.L.; Stapleton, J.T. Effect of coinfection with GB virus C on survival among patients with HIV infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.F.; Klinzman, D.; Yamashita, T.E.; Xiang, J.; Polgreen, P.M.; Rinaldo, C.; Liu, C.; Phair, J.; Margolick, J.B.; Zdunek, D.; et al. Persistent GB virus C infection and survival in HIV-infected men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deme, P.; Rubin, L.H.; Yu, D.; Xu, Y.; Nakigozi, G.; Nakasujja, N.; Anok, A.; Kisakye, A.; Quinn, T.C.; Reynolds, S.J.; et al. Immunometabolic Reprogramming in Response to HIV Infection Is Not Fully Normalized by Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy. Viruses 2022, 14, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gootenberg, D.B.; Paer, J.M.; Luevano, J.M.; Kwon, D.S. HIV-associated changes in the enteric microbial community: Potential role in loss of homeostasis and development of systemic inflammation. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 30, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Body Site | Eukaryotic Viruses | Phages |

|---|---|---|

| Blood | Anelloviridae | Inoviridae |

| Herpesviridae | Microviridae | |

| Picornaviridae | Myoviridae | |

| Podoviridae | ||

| Siphoviridae | ||

| Skin | Adenoviridae | Myoviridae |

| Anelloviridae | Podoviridae | |

| Circoviridae | Siphoviridae | |

| Herpesviridae | ||

| Papillomaviridae | ||

| Polyomaviridae | ||

| Nervous System | Herpesviridae | Myoviridae |

| Podoviridae | ||

| Siphoviridae | ||

| Oral Cavity | Anelloviridae | Myoviridae |

| Herpesviridae | Podoviridae | |

| Papillomaviridae | Siphoviridae | |

| Redondoviridae | ||

| Lung | Adenoviridae | Inoviridae |

| Anelloviridae | Microviridae | |

| Herpesviridae | Myoviridae | |

| Papillomaviridae | Podoviridae | |

| Redondoviridae | Siphoviridae | |

| Gastrointestinal Tract | Adenoviridae | Inoviridae |

| Anelloviridae | Microviridae | |

| Caliciviridae | Myoviridae | |

| Circoviridae | Podoviridae | |

| Herpesviridae | Siphoviridae | |

| Picornaviridae | ||

| Virgaviridae | ||

| Urinary System | Papillomaviridae | Myoviridae |

| Polyomaviridae | Podoviridae | |

| Herpesviridae | Siphoviridae | |

| Vagina | Anelloviridae | Microviridae |

| Herpesviridae | Myoviridae | |

| Podoviridae | ||

| Siphoviridae | ||

| Semen | Anelloviridae | Unknown |

| Herpesviridae | ||

| Papillomaviridae |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cesanelli, F.; Scarvaglieri, I.; De Francesco, M.A.; Alberti, M.; Salvi, M.; Tiecco, G.; Castelli, F.; Quiros-Roldan, E. The Human Virome in Health and Its Remodeling During HIV Infection and Antiretroviral Therapy: A Narrative Review. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010050

Cesanelli F, Scarvaglieri I, De Francesco MA, Alberti M, Salvi M, Tiecco G, Castelli F, Quiros-Roldan E. The Human Virome in Health and Its Remodeling During HIV Infection and Antiretroviral Therapy: A Narrative Review. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010050

Chicago/Turabian StyleCesanelli, Federico, Irene Scarvaglieri, Maria Antonia De Francesco, Maria Alberti, Martina Salvi, Giorgio Tiecco, Francesco Castelli, and Eugenia Quiros-Roldan. 2026. "The Human Virome in Health and Its Remodeling During HIV Infection and Antiretroviral Therapy: A Narrative Review" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010050

APA StyleCesanelli, F., Scarvaglieri, I., De Francesco, M. A., Alberti, M., Salvi, M., Tiecco, G., Castelli, F., & Quiros-Roldan, E. (2026). The Human Virome in Health and Its Remodeling During HIV Infection and Antiretroviral Therapy: A Narrative Review. Microorganisms, 14(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010050