Study on the Enrichment Effect of Suillus luteus Polysaccharide on Intestinal Probiotics and the Immunomodulatory Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Animals and Cells

2.3. Extraction of SLP

2.4. Chemical Composition Analysis of SLP

2.5. Average Molecular Weight and Monosaccharide Composition Analysis of SLP

2.6. Detection of Primary Functional Groups in SLP

2.7. Micro-Morphological Observation of SLP

2.8. Glycosidic Bond Detection

2.9. Animal Experiment Design

2.10. Physiological Parameter Assessment

2.11. 16S Amplicon Detection Method

2.12. Detection of Gut Microbiota Metabolites

2.13. Methodology for Lymphocyte Subpopulation Analysis

2.14. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Structural Analysis of SLP

3.2. One-Dimensional Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Analysis of SLP

3.3. Two-Dimensional NMR Spectral Analysis of SLP

3.4. Effects of SLP on Physiological Parameters in Tumor-Bearing Mice

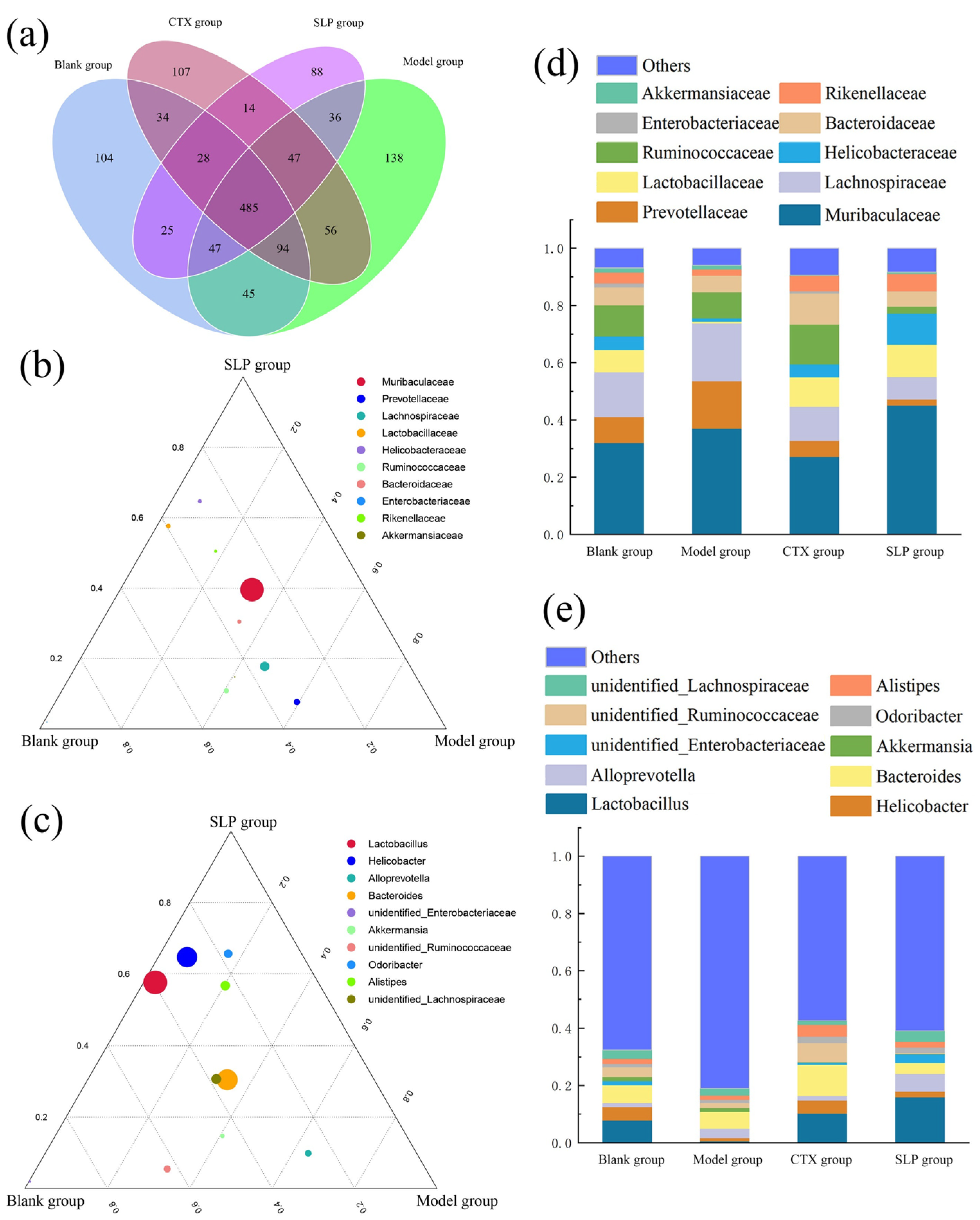

3.5. Effects of SLP on Gut Microbiota Diversity in Tumor-Bearing Mice

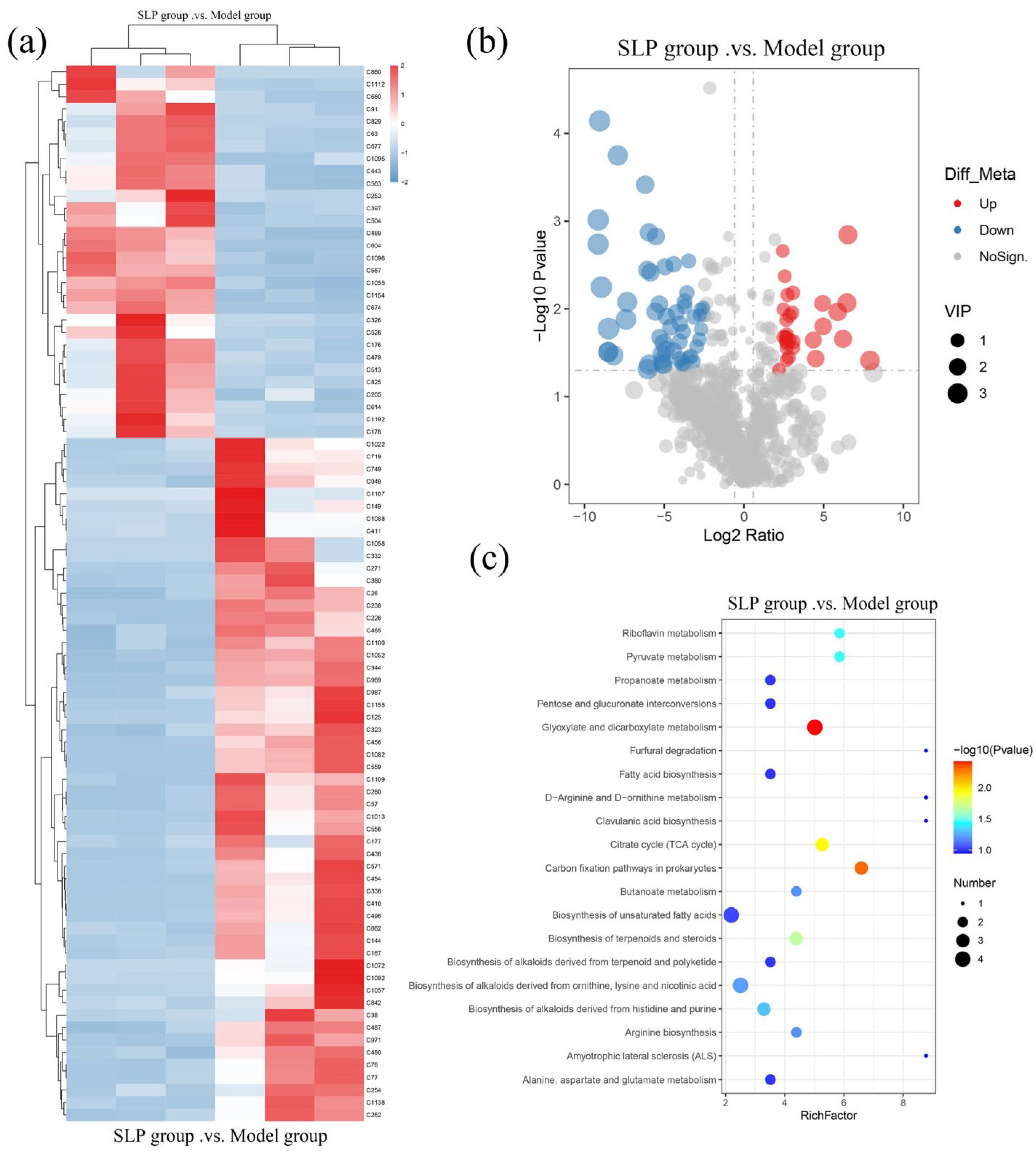

3.6. Effects of SLP on Gut Microbiota Metabolites in Tumor-Bearing Mice

3.7. Effects of SLP on T Cell Subset Distributions in Tumor-Bearing Mice

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murata, H.; Yamada, A.; Yokota, S.; Maruyama, T.; Shimokawa, T.; Neda, H. Innate traits of Pinaceae-specific ectomycorrhizal symbiont Suillus luteus that differentially associates with arbuscular mycorrhizal broad-leaved trees in vitro. Mycoscience 2015, 56, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hao, L.; Zhang, A.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, B. Extraction and characterization of polysaccharides from Schisandra sphenanthera fruit by Lactobacillus plantarum CICC 23121-assisted fermentation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, S.; Zhang, X.; Xie, J.; Ye, X.; Zhang, X. Change of microbial communities in heavy metals-contaminated rhizosphere soil with ectomycorrhizal fungi Suillus luteus inoculation. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 190, 105019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Muratkhan, M.; Liu, M.; Lü, X.; Wang, X. Recent advances in the application of subcritical water to plant and fungi polysaccharides preparation: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 322, 146720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, T.T.; Maria, C.T.; Debiasi, A.M.; Vieira, H.C.; Ballod, T.L.B. Mushroom β-glucans: Application and innovation for food industry and immunotherapy. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 5035–5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, Q.; Hou, C.; Liang, J.; Guan, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; He, Y. Lycium barbarum polysaccharide suppresses uridine induced malignant progression of lung adenocarcinoma via UPP1 regulation. Cell Investig. 2025, 2, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Tong, H.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, X. Nutrient acquisition of gut microbiota: Implications for tumor immunity. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2025, 114, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Gao, G.; He, Q.; Kwok, L.-Y.; Sun, Z. The gut-tumor connection: The role of microbiota in cancer progression and treatment strategies. J. Adv. Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Long, Y.; Chi, J.; Dai, K.; Jia, X.; Ji, H. Effects of Ethanol Concentrations on Primary Structural and Bioactive Characteristics of Dendrobium officinale Polysaccharides. Nutrients 2024, 16, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.Y.; Liu, C.; Ji, H.Y.; Liu, A.J. Structural characteristics and anti-tumor activity of alkali-extracted acidic polysaccharide extracted from Panax ginseng. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 305, 141230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modugno, F.; Łucejko, J.J. Monosaccharide composition of lignocellulosic matrix—Optimization of microwave-assisted acid hydrolysis condition. Talanta Open 2024, 9, 100312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monika, S.-C.; Patrycja, P.; Anna, S.-K.; Artur, Z. A determination of the composition and structure of the polysaccharides fractions isolated from apple cell wall based on FT-IR and FT-Raman spectra supported by PCA analysis. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 150, 109688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.Q.; An, H.X.; Ma, R.J.; Dai, K.Y.; Ji, H.Y.; Liu, A.J.; Zhou, J.P. Structural characteristics of a low molecular weight velvet antler protein and the anti-tumor activity on S180 tumor-bearing mice. Bioorganic Chem. 2022, 131, 106304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Y.; Yang, J.; Ji, H.; Han, X.; Fan, Y.; Dai, K.; Ji, H.; Yu, J. Preparation Process Optimization of Glycolipids from Dendrobium officinale and the Difference in Antioxidant Effects Compared with Ascorbic Acid. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Fan, Y.; Dai, K.; Zheng, G.; Jia, X.; Han, B.; Xu, B.; Ji, H. Structural characterization of an acid-extracted polysaccharide from Suillus luteus and the regulatory effects on intestinal flora metabolism in tumor-bearing mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 136137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.-X.; Ma, R.-J.; Cao, T.-Q.; Liu, C.; Ji, H.-Y.; Liu, A.-J. Preparation and anti-tumor effect of pig spleen ethanol extract against mouse S180 sarcoma cells in vivo. Process Biochem. 2023, 130, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Cooper, V.S.; Zemke, A.C. Evaluation of V3–V4 and FL-16S rRNA amplicon sequencing approach for microbiota community analysis of tracheostomy aspirates. mSphere 2025, 10, e00388-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parralejo-Sanz, S.; Requena, T.; Cano, M.P. Biotransformation of Opuntia stricta var. dillenii extracts by human gut microbiota: Evolution of betalains and phenolic compounds, and formation of secondary metabolites. Food Biosci. 2025, 74, 107835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.V.N.; Hargarten, J.C.; Wang, R.; Carlson, D.; Park, Y.-D.; Specht, C.A.; Williamson, P.R.; Levitz, S.M. Peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses to Cryptococcus candidate vaccine antigens in human subjects with and without cryptococcosis. J. Infect. 2025, 91, 106521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Er, M.; Nermin, O. Bioactive interpenetrating hybrids of poly(hydroxyethyl methacrylate-co-glycidyl methacrylate): Effect of polysaccharide types on structural peculiarities and multifunctionality. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 254, 127807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, X.; Du, X.; Li, F.; Wang, T.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J.; Luo, X.; Guo, X.; Tang, Z. Ultrasound-Assisted extraction and purification of polysaccharides from Boschniakia rossica: Structural Characterization and antioxidant potential. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2025, 118, 107364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, M.L.; Bols, M. 2A,6A−F-Hepta-O-tert-butyldimethylsilyl α-cyclodextrin—A carbohydrate undecaol with all OH groups visible in NMR indicative of a partially disrupted hydrogen bond network. Carbohydr. Res. 2025, 548, 109354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.; Fan, Y.; Long, Y.; Dai, K.; Zheng, G.; Jia, X.; Liu, A.; Yu, J. Structural analysis of Salvia miltiorrhiza polysaccharide and its regulatory functions on T cells subsets in tumor-bearing mice combined with thymopentin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 133832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Liu, M.; Wei, Y.; Tong, L.; Guo, S.; Kang, H.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Duan, J.-a. Structural characteristics and structure-activity relationship of four polysaccharides from Lycii fructus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Ding, X.-Y.; Li, X.-H.; Gong, M.-J.; An, J.-Q.; Huang, S.-L. Correlation between elevated inflammatory cytokines of spleen and spleen index in acute spinal cord injury. J. Neuroimmunol. 2020, 344, 577264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Feng, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, P.; Zhang, T.; Han, Z.; Tang, C.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Cordycepin attenuated cyclophosphamide (CTX)-induced immunosuppression in mice via EGFR/Nrf2 antioxidant signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 163, 115235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; La, J.; Park, W.H.; Kim, H.-J.; Park, S.H.; Ku, K.B.; Kang, B.H.; Lim, J.; Kwon, M.S.; et al. Supplementation with a high-glucose drink stimulates anti-tumor immune responses to glioblastoma via gut microbiota modulation. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 113220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.-F.; Li, M.; Han, X.; Fan, Y.-T.; Yang, J.-J.; Long, Y.; Yu, J.; Ji, H.-Y. Lactobacilli-Mediated Regulation of the Microbial–Immune Axis: A Review of Key Mechanisms, Influencing Factors, and Application Prospects. Foods 2025, 14, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, S.F.; Gogokhia, L.; Viladomiu, M.; Chou, L.; Putzel, G.; Jin, W.-B.; Pires, S.; Guo, C.-J.; Gerardin, Y.; Crawford, C.V.; et al. Transferable Immunoglobulin A–Coated Odoribacter splanchnicus in Responders to Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Ulcerative Colitis Limits Colonic Inflammation. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-Y.; Wu, Q.-W.; Han, Y.; Xiang, S.-J.; Wang, Y.-N.; Wu, W.-W.; Chen, Y.-X.; Feng, Z.-Q.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Xu, Z.-G.; et al. Alistipes finegoldii augments the efficacy of immunotherapy against solid tumors. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 1714–1730.e1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hao, J.; Li, Y.; Zou, Y.; Li, A.; Fan, Y.; Ma, S.; Hao, S.; Yu, S.; Shen, D.; et al. Engineered self-assembly of mucoadhesive Helicobacter pylori vaccines: CD4+ T cell-dependent immunity prevents bacterial colonization. J. Control. Release 2026, 389, 114417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.-P.; Zhou, H.-L.; Chen, H.-B.; Zheng, M.-Y.; Liang, Y.-W.; Gu, Y.-T.; Li, W.-T.; Qiu, W.-L.; Zhou, H.-G. Gut microbiota interactions with antitumor immunity in colorectal cancer: From understanding to application. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mailloux, R.J.; Puiseux-Dao, S.; Appanna, V.D. α-Ketoglutarate abrogates the nuclear localization of HIF-1α in aluminum-exposed hepatocytes. Biochimie 2009, 91, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Liu, J.; Zhao, N.; Wong, I.N.; Huang, R. Caulerpa chemnitzia polysaccharide exerts immunomodulatory activity in macrophages by mediating the succinate/PHD2/HIF-1α/IL-1β pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Chen, G.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, W.; Qi, S.; Xue, X.; Wang, K.; Wu, L. Effects of dietary phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin on DSS-induced colitis by regulating metabolism and gut microbiota in mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 105, 109004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munhoz, J.; Mazurak, V.; Field, C.J. Perspective: Implications of Docosahexaenoic Acid and Eicosapentaenoic Acid Supplementation on the Immune System during Cancer Chemotherapy: Perspectives from Current Clinical Evidence. Adv. Nutr. 2025, 16, 100464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, I.; Sluis, K.; Aryal, P.; Solomon, Z.; Patel, R.; Konduri, S.; Siegel, D.; Smith, U.; Kahn, B.B. Specific FAHFAs predict worsening glucose tolerance in non-diabetic relatives of people with Type 2 diabetes. J. Lipid Res. 2025, 66, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacorta, L.; Minarrieta, L.; Salvatore, S.R.; Khoo, N.K.; Rom, O.; Gao, Z.; Berman, R.C.; Jobbagy, S.; Li, L.; Woodcock, S.R.; et al. In situ generation, metabolism and immunomodulatory signaling actions of nitro-conjugated linoleic acid in a murine model of inflammation. Redox Biol. 2018, 15, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gram, D.Y.; Şentürk, M.; Kamacı Özocak, G.; Doğan, N.D.; Ekebaş, G.; Atasever, A.; Eren, M. Effect of dietary L-arginine supplementation on the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor A, its receptors, and nitric oxide system components in the pancreas of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Tissue Cell 2025, 97, 103072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboul-Fotouh, S.; Zohny, S.M.; Hassan, G.A.M.; Eissa, A.M.; Elshahawi, H.H.; Abdelraouf, S.M.; Ahmed, M.Y.; Rabei, M.R.; Hassan, F.E.; Mahmoud, A.N.; et al. Blockade of NMDA-receptors mitigates autistic and cognitive behaviors via modulation of TLR-4/NLRP3 inflammasomes and microglia/astrocyte crosstalk in rat model of autism. NeuroToxicology 2025, 111, 103350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonini Cencicchio, M.; Montini, F.; Palmieri, V.; Massimino, L.; Lo Conte, M.; Finardi, A.; Mandelli, A.; Asnicar, F.; Pavlovic, R.; Drago, D.; et al. Microbiota-produced immune regulatory bile acid metabolites control central nervous system autoimmunity. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffitt, C.; Bidkhori, G.; Lee, S.; Tebani, A.; Mardinoglu, A.; Uhlen, M.; Moyes, D.L.; Shoaie, S. Genome-scale metabolic modelling of the human gut microbiome reveals changes in the glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism in metabolic disorders. iScience 2022, 25, 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Tomtong, P.; Charoensiddhi, S.; Vongsangnak, W. Exploring Morchella esculenta polysaccharide extracts: In vitro digestion, fermentation characteristics, and prebiotic potential for modulating gut microbiota and function. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 318, 144910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Ma, P.; Fan, Q.; Yu, H.; Peng, Y.; Li, X. Yanning Syrup ameliorates the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation: Adjusting the gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, and the CD4+ T cell balance. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 283, 114729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Peng, J.; Zhang, C.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hou, Y.; Fan, T.; Fan, T.; Wang, J. Immunomodulatory mechanism of Radix Bupleuri polysaccharide on RAW264.7 cells and cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 327, 147092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Q.; Liu, N.; Jiang, S.; Deng, Y. Melatonin Inhibits CD4+T Cell Apoptosis via the Bcl-2/BAX Pathway and Improves Survival Rates in Mice With Sepsis. J. Pineal Res. 2025, 77, e70071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celorrio, M.; Shumilov, K.; Ni, A.; Ayerra, L.; Self, W.K.; de Francisca, N.L.V.; Rodgers, R.; Schriefer, L.A.; Garcia, B.; Aymerich, M.S.; et al. Short-chain fatty acids are a key mediator of gut microbial regulation of T cell trafficking and differentiation after traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 392, 115349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayana, K.; Jelin, V.; Alex, Y. Impact of diabetes on CD4 expression in T lymphocytes: A comparative analysis postCovishield vaccination. Vacunas 2025, 26, 500431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Description | Retention Time (min) | m/z | log2FC | p-Value | Up/Down |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1013 | Uridine | 0.58 | 243.06 | −5.86 | 0.00 | down |

| C1022 | Xylobiose | 7.49 | 281.09 | −3.77 | 0.04 | down |

| C1052 | N-L-Acetyl-arginine | 0.55 | 215.11 | −5.14 | 0.04 | down |

| C1057 | 1-linoleic acid glyceride | 9.44 | 353.27 | −4.96 | 0.00 | down |

| C1058 | α-ketoglutaric acid | 17.47 | 145.01 | −8.51 | 0.03 | down |

| C1072 | Cholesterol sulfate | 10.22 | 465.30 | −5.29 | 0.02 | down |

| C1082 | Glyceric acid | 0.54 | 105.02 | −9.05 | 0.00 | down |

| C1088 | Malic acid | 0.57 | 133.01 | −3.81 | 0.02 | down |

| C1092 | N-acetylgalactosamine | 0.52 | 220.08 | −6.06 | 0.00 | down |

| C1100 | Picolinic acid | 0.59 | 122.02 | −2.50 | 0.01 | down |

| C1107 | Succinic acid | 10.86 | 117.02 | −8.18 | 0.03 | down |

| C1109 | Tricarboxylic acid | 16.93 | 175.02 | −4.60 | 0.02 | down |

| C1138 | Anacardic acid | 7.76 | 347.26 | −4.24 | 0.01 | down |

| C1155 | LPG18:2 | 6.86 | 507.27 | −6.20 | 0.00 | down |

| C125 | 2,6-Dihydroxypurine | 0.58 | 151.03 | −9.15 | 0.00 | down |

| C144 | 2-Hydroxybutanoicacid | 0.93 | 103.04 | −4.41 | 0.00 | down |

| C149 | 2-Hydroxyvalericacid | 0.62 | 117.06 | −5.94 | 0.04 | down |

| C177 | 3-Deoxy-lyxo-heptulosaricacid | 7.97 | 221.03 | −3.46 | 0.04 | down |

| C187 | 3-Hydroxybutyricacid | 0.60 | 103.04 | −3.58 | 0.01 | down |

| C226 | 4-Hydroxy-2-oxo-heptanedioate | 0.57 | 189.04 | −4.87 | 0.01 | down |

| C238 | 4-Pyridoxicacid | 0.78 | 182.05 | −8.95 | 0.01 | down |

| C254 | 5-oxo-3-phenyl-5-(2-quinolinylamino)pentanoic acid | 3.53 | 335.14 | −2.96 | 0.03 | down |

| C26 | (9R,10R)-Dihydroxyoctadecanoic acid | 6.83 | 315.25 | −3.13 | 0.01 | down |

| C260 | 6-Deoxy-L-altrose | 0.60 | 163.06 | −5.10 | 0.04 | down |

| C262 | 6-Keto-prostaglandinF1a | 0.42 | 369.23 | −4.00 | 0.04 | down |

| C271 | 7-Methylxanthine | 0.55 | 165.04 | −5.97 | 0.00 | down |

| C323 | Adonitol | 0.53 | 151.06 | −3.34 | 0.03 | down |

| C332 | alpha-Ketoglutaric acid | 0.55 | 145.01 | −8.52 | 0.03 | down |

| C338 | Apiose | 0.55 | 149.05 | −7.32 | 0.01 | down |

| C344 | Behenic acid | 11.83 | 339.33 | −4.01 | 0.01 | down |

| C38 | 1-(2,6-difluorobenzyl)piperidine hydrochloride | 0.53 | 212.12 | −3.66 | 0.04 | down |

| C380 | Cholic acid | 4.72 | 407.28 | −3.47 | 0.00 | down |

| C410 | D-(−)-Ribose | 0.55 | 149.05 | −7.40 | 0.01 | down |

| C411 | D-(+)-Malic acid | 0.55 | 133.01 | −4.03 | 0.02 | down |

| C438 | Dimethyl fumarate | 0.58 | 143.03 | −4.89 | 0.03 | down |

| C450 | DL-o-Tyrosine | 2.87 | 182.08 | −2.79 | 0.02 | down |

| C454 | Docosahexaenoic acid | 8.55 | 327.23 | −7.91 | 0.00 | down |

| C456 | Docosapentaenoic acid | 8.93 | 329.25 | −5.52 | 0.00 | down |

| C465 | Ecgonine | 3.25 | 186.11 | −2.68 | 0.02 | down |

| C487 | FAHFA(18:2/18:1) | 8.84 | 559.47 | −2.72 | 0.01 | down |

| C496 | Galactonic acid | 0.57 | 195.05 | −6.04 | 0.05 | down |

| C556 | Ketodeoxyoctonic acid | 0.88 | 237.06 | −5.04 | 0.02 | down |

| C559 | L-(−)-Glyceric acid | 0.58 | 105.02 | −9.14 | 0.00 | down |

| C57 | 1,5-Anhydro-D-glucitol | 0.55 | 163.06 | −5.06 | 0.04 | down |

| C571 | L-glycero-D-manno-heptose | 8.63 | 209.07 | −5.16 | 0.03 | down |

| C719 | Neomentholglucuronide | 6.24 | 331.18 | −4.42 | 0.03 | down |

| C749 | Oxoadipic Acid | 0.55 | 159.03 | −5.56 | 0.01 | down |

| C76 | 13,14-dihydro-15-ketoProstaglandinE2 | 8.14 | 351.22 | −3.71 | 0.01 | down |

| C77 | 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto-PGE2 | 9.25 | 351.22 | −3.72 | 0.01 | down |

| C842 | PC(14:0/P-16:0) | 13.13 | 690.54 | −3.17 | 0.04 | down |

| C862 | PC(O-16:0/18:2(9Z,12Z)) | 0.52 | 744.59 | −2.77 | 0.01 | down |

| C949 | SM(d18:0/16:1(9Z)(OH)) | 8.77 | 717.55 | −2.56 | 0.01 | down |

| C969 | Stearic acid | 9.94 | 283.26 | −8.49 | 0.02 | down |

| C971 | Stercobilin | 10.18 | 593.33 | −5.31 | 0.01 | down |

| C987 | Tetrahydro-11-deoxycortisol | 8.90 | 349.24 | −3.85 | 0.04 | down |

| C1055 | ProstaglandinF1 | 7.60 | 355.25 | 2.68 | 0.02 | up |

| C1095 | N-methyl-D-aspartate | 6.07 | 148.06 | 2.47 | 0.02 | up |

| C1096 | Oleinglyceride | 10.11 | 355.29 | 2.44 | 0.00 | up |

| C1112 | VitaminB2 | 3.87 | 375.13 | 3.02 | 0.01 | up |

| C1154 | LPC20:5 | 5.32 | 540.31 | 4.50 | 0.04 | up |

| C1192 | N-morpholino-N-[(5-nitro-3-thienyl)carbonyl]urea | 4.01 | 301.06 | 4.94 | 0.01 | up |

| C176 | 3-dehydrocholicacid | 6.73 | 407.28 | 3.09 | 0.02 | up |

| C178 | 3-Hydroxy-11Z-octadecenoylcarnitine | 7.15 | 442.35 | 2.71 | 0.02 | up |

| C205 | 3-Oxo-5β-cholanate | 8.00 | 373.27 | 2.21 | 0.05 | up |

| C253 | 5-Methoxyindoleaceticacid | 4.06 | 204.07 | 4.97 | 0.02 | up |

| C326 | AL8810Methylester | 2.73 | 417.24 | 2.61 | 0.02 | up |

| C397 | Creatinine | 0.57 | 114.07 | 2.47 | 0.01 | up |

| C443 | DL-Arginine | 0.55 | 175.12 | 2.65 | 0.02 | up |

| C479 | ethyl5-hydroxy-4-oxo-4H-chromene-2-carboxylate | 0.50 | 235.06 | 2.81 | 0.04 | up |

| C489 | FAHFA (2:0/21:0) | 10.08 | 383.32 | 2.56 | 0.00 | up |

| C504 | Genipin | 3.44 | 225.08 | 2.87 | 0.01 | up |

| C513 | Glycocholic acid | 10.42 | 466.32 | 3.08 | 0.03 | up |

| C526 | HET0016 | 0.47 | 207.15 | 3.07 | 0.01 | up |

| C563 | L-Arginine | 9.18 | 175.12 | 2.65 | 0.02 | up |

| C567 | Ethyllaurate | 8.62 | 227.20 | 5.88 | 0.01 | up |

| C604 | LPC22:5 | 7.47 | 568.34 | 6.52 | 0.00 | up |

| C614 | LPE22:5 | 7.06 | 528.31 | 2.66 | 0.01 | up |

| C63 | 10-Nitrolinoleate | 7.12 | 326.23 | 2.68 | 0.03 | up |

| C660 | LysoPE(0:0/22:5(4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z)) | 6.25 | 528.31 | 2.73 | 0.01 | up |

| C674 | Myristic acid | 8.60 | 227.20 | 6.46 | 0.01 | up |

| C677 | N-(3-Hydroxy-7-cis-tetradecenoyl)homoserinelactone | 4.13 | 326.23 | 2.69 | 0.04 | up |

| C825 | PC (19:1/20:5) | 7.98 | 820.59 | 4.35 | 0.02 | up |

| C829 | PC (20:3/20:4) | 13.32 | 832.59 | 6.22 | 0.02 | up |

| C860 | PC (20:3(5Z,8Z,11Z)/20:3(5Z,8Z,11Z)) | 3.88 | 834.60 | 7.91 | 0.04 | up |

| C91 | 1-Hexadecanoyl-2-(9Z-octadecenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phospho-1-myo-inositol | 13.21 | 837.55 | 2.87 | 0.02 | up |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ji, H.; Li, M.; Wang, R.; Mao, D.; Ji, Z.; Peng, L.; Ding, W.; Ji, H. Study on the Enrichment Effect of Suillus luteus Polysaccharide on Intestinal Probiotics and the Immunomodulatory Activity. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010004

Ji H, Li M, Wang R, Mao D, Ji Z, Peng L, Ding W, Ji H. Study on the Enrichment Effect of Suillus luteus Polysaccharide on Intestinal Probiotics and the Immunomodulatory Activity. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Hongfei, Mei Li, Ruxue Wang, Decheng Mao, Zhuoyang Ji, Lizeng Peng, Wenjie Ding, and Haiyu Ji. 2026. "Study on the Enrichment Effect of Suillus luteus Polysaccharide on Intestinal Probiotics and the Immunomodulatory Activity" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010004

APA StyleJi, H., Li, M., Wang, R., Mao, D., Ji, Z., Peng, L., Ding, W., & Ji, H. (2026). Study on the Enrichment Effect of Suillus luteus Polysaccharide on Intestinal Probiotics and the Immunomodulatory Activity. Microorganisms, 14(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010004