From Single Organisms to Communities: Modeling Methanotrophs and Their Satellites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. System Biology Approaches for Analysis of Microbial Metabolic Networks and Community Interactions

3. Methanotroph’s Satellites

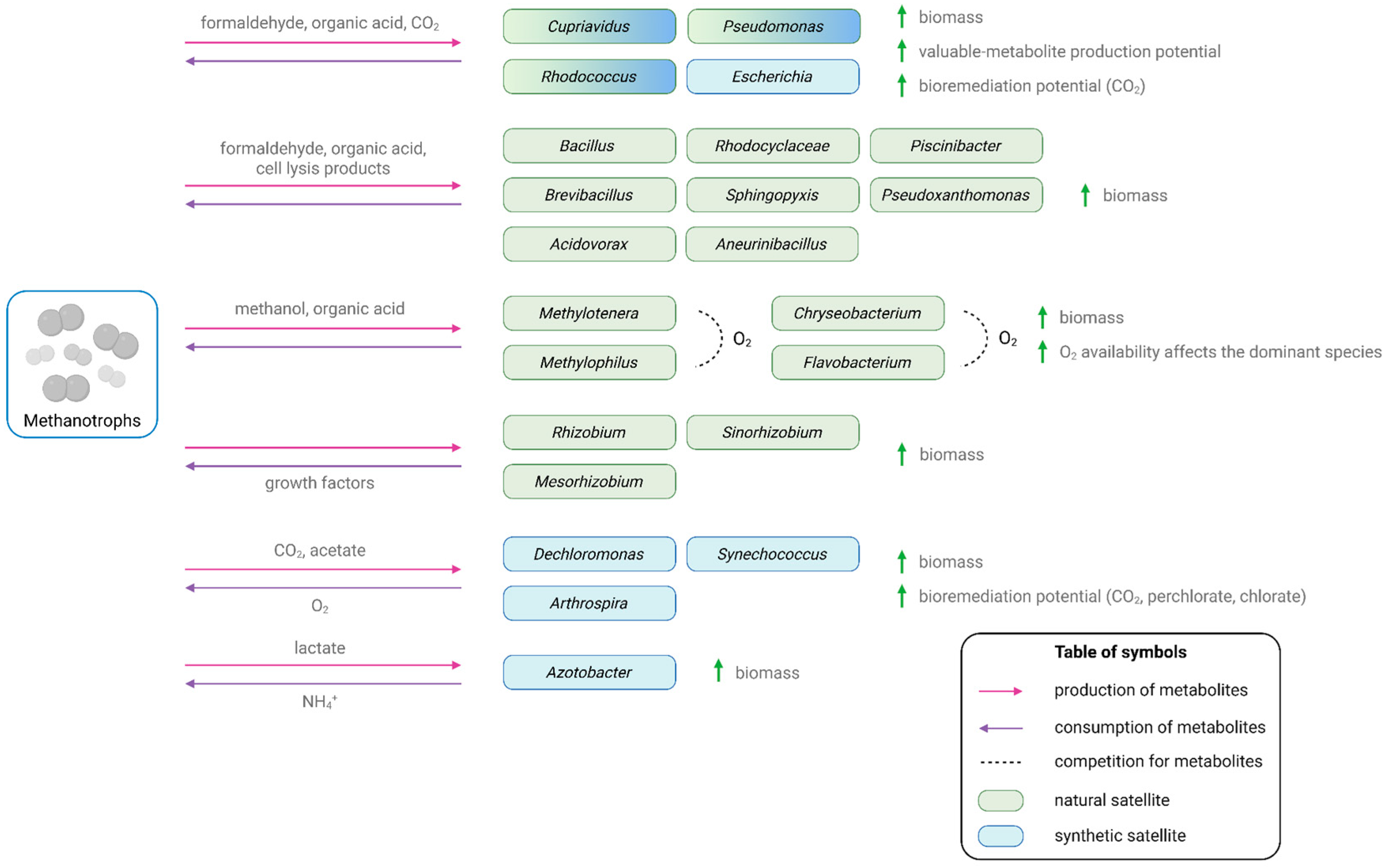

3.1. Natural Methanotroph’s Satellites

3.1.1. Satellites That Promote a Methanotroph’s Growth by Consuming Metabolic By-Products

3.1.2. Satellites That Promote Methanotroph Growth by Producing Growth Factors

3.2. Potential Methanotroph’s Satellites

3.2.1. Synthetic Methanotrophic Communities for the Production of Metabolites

3.2.2. Synthetic Methanotrophic Communities for Bioremediation

4. Mathematical Models of Methanotroph’s Satellites

4.1. Genomes-Scale Mathematical Models

4.1.1. Strain-to-Strain Models

4.1.2. Models of Closely Related Strains

4.1.3. Non-Curated Models

4.2. Genome-Scale Mathematical Models with dFBA

4.3. Assessment of Satellite Models Quality

5. Community Models of Methanotrophs and Satellites

5.1. Genome-Scale Community Models

5.2. Genome-Scale Community Models with dFBA

5.3. Other Community Models

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strong, P.J.; Xie, S.; Clarke, W.P. Methane as a Resource: Can the Methanotrophs Add Value? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 4001–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyuzhnaya, M.G.; Puri, A.W.; Lidstrom, M.E. Metabolic Engineering in Methanotrophic Bacteria. Metab. Eng. 2015, 29, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyuzhnaya, M.G.; Gomez, O.A.; Murrell, J.C. The Methane-Oxidizing Bacteria (Methanotrophs). In Taxonomy, Genomics and Ecophysiology of Hydrocarbon-Degrading Microbes; McGenity, T.J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 245–278. ISBN 978-3-030-14795-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, R.S.; Hanson, T.E. Methanotrophic Bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 1996, 60, 439–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semrau, J.D.; DiSpirito, A.A.; Gu, W.; Yoon, S. Metals and Methanotrophy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02289-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothe, H.; Jensen, K.M.; Mergel, A.; Larsen, J.; Jørgensen, C.; Bothe, H.; Jorgensen, L.N. Heterotrophic Bacteria Growing in Association with Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) in a Single Cell Protein Production Process. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 59, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshkin, I.Y.; Belova, S.; Khokhlachev, N.; Semenova, V.; Chervyakova, O.; Chernushkin, D.; Tikhonova, E.; Mardanov, A.; Ravin, N.; Popov, V.; et al. Molecular Analysis of the Microbial Community Developing in Continuous Culture of Methylococcus sp. Concept-8 on Natural Gas. Microbiology 2020, 89, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iguchi, H.; Yurimoto, H.; Sakai, Y. Stimulation of Methanotrophic Growth in Cocultures by Cobalamin Excreted by Rhizobia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 8509–8515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.E.; Beck, D.A.C.; Lidstrom, M.E.; Chistoserdova, L. Oxygen Availability Is a Major Factor in Determining the Composition of Microbial Communities Involved in Methane Oxidation. PeerJ 2015, 3, e801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, N.; Sakarika, M.; Kerckhof, F.-M.; Law, C.K.Y.; De Vrieze, J.; Rabaey, K. Microbial Protein Production from Methane via Electrochemical Biogas Upgrading. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 391, 123625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwautz, C.; Kus, G.; Stöckl, M.; Neu, T.R.; Lueders, T. Microbial Megacities Fueled by Methane Oxidation in a Mineral Spring Cave. ISME J. 2018, 12, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaresan, D.; Stephenson, J.; Doxey, A.C.; Bandukwala, H.; Brooks, E.; Hillebrand-Voiculescu, A.; Whiteley, A.S.; Murrell, J.C. Aerobic Proteobacterial Methylotrophs in Movile Cave: Genomic and Metagenomic Analyses. Microbiome 2018, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenzinger, K.; Glatter, T.; Hakobyan, A.; Meima-Franke, M.; Zweers, H.; Liesack, W.; Bodelier, P.L.E. Exploring Modes of Microbial Interactions with Implications for Methane Cycling. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2024, 100, fiae112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugenholtz, P. Exploring Prokaryotic Diversity in the Genomic Era. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, reviews0003-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodor, A.; Bounedjoum, N.; Vincze, G.E.; Erdeiné Kis, Á.; Laczi, K.; Bende, G.; Szilágyi, Á.; Kovács, T.; Perei, K.; Rákhely, G. Challenges of Unculturable Bacteria: Environmental Perspectives. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, G.; Sani, R.K. Molecular Techniques to Assess Microbial Community Structure, Function, and Dynamics in the Environment. In Microbes and Microbial Technology; Ahmad, I., Ahmad, F., Pichtel, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 29–57. ISBN 978-1-4419-7930-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhi, W.; Ge, Z.; He, Z.; Zhang, H. Methods for Understanding Microbial Community Structures and Functions in Microbial Fuel Cells: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 171, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisener, C.G.; Reid, T. Combined Imaging and Molecular Techniques for Evaluating Microbial Function and Composition: A Review. Surf. Interface Anal. 2017, 49, 1416–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, N.S.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. Synthetic Biology Tools to Engineer Microbial Communities for Biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuszyńska, A.; Ebenhöh, O.; Zurbriggen, M.D.; Ducat, D.C.; Axmann, I.M. A New Era of Synthetic Biology—Microbial Community Design. Synth. Biol. 2024, 9, ysae011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Berg, N.I.; Machado, D.; Santos, S.; Rocha, I.; Chacón, J.; Harcombe, W.; Mitri, S.; Patil, K.R. Ecological Modelling Approaches for Predicting Emergent Properties in Microbial Communities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 6, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Lan, F.; Venturelli, O.S. Towards a Deeper Understanding of Microbial Communities: Integrating Experimental Data with Dynamic Models. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021, 62, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos Rodriguez-Conde, F.; Zhu, S.; Dikicioglu, D. Harnessing Microbial Division of Labor for Biomanufacturing: A Review of Laboratory and Formal Modeling Approaches. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2025, 45, 1249–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oña, L.; Shreekar, S.K.; Kost, C. Disentangling Microbial Interaction Networks. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 33, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santillan, E.; Neshat, S.A.; Wuertz, S. Disturbance and Stability Dynamics in Microbial Communities for Environmental Biotechnology Applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2025, 93, 103304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Succurro, A.; Moejes, F.W.; Ebenhöh, O. A Diverse Community To Study Communities: Integration of Experiments and Mathematical Models To Study Microbial Consortia. J. Bacteriol. 2017, 199, 00865-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, S.; Jnana, A.; Murali, T.S. Modeling Microbial Community Networks: Methods and Tools for Studying Microbial Interactions. Microb. Ecol. 2024, 87, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardona, C.; Weisenhorn, P.; Henry, C.; Gilbert, J.A. Network-Based Metabolic Analysis and Microbial Community Modeling. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2016, 31, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.; Angel, R.; Veraart, A.J.; Daebeler, A.; Jia, Z.; Kim, S.Y.; Kerckhof, F.-M.; Boon, N.; Bodelier, P.L.E. Biotic Interactions in Microbial Communities as Modulators of Biogeochemical Processes: Methanotrophy as a Model System. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonze, D.; Coyte, K.Z.; Lahti, L.; Faust, K. Microbial Communities as Dynamical Systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2018, 44, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.D.; Olivença, D.V.; Brown, S.P.; Voit, E.O. Methods of Quantifying Interactions among Populations Using Lotka-Volterra Models. Front. Syst. Biol. 2022, 2, 1021897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Overview of Some Theoretical Approaches for Derivation of the Monod Equation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 73, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.; Mayr, M.J.; Bouffard, D.; Wehrli, B.; Bürgmann, H. Trait-Based Model Reproduces Patterns of Population Structure and Diversity of Methane Oxidizing Bacteria in a Stratified Lake. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 833511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiciudean, I.; Russo, G.; Bogdan, D.F.; Levei, E.A.; Faur, L.; Hillebrand-Voiculescu, A.; Moldovan, O.T.; Banciu, H.L. Competition-Cooperation in the Chemoautotrophic Ecosystem of Movile Cave: First Metagenomic Approach on Sediments. Environ. Microbiome 2022, 17, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, K.; He, Q.P.; Wang, J. Probing Interspecies Metabolic Interactions within a Synthetic Binary Microbiome Using Genome-Scale Modeling. Microbiome Res. Rep. 2024, 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esembaeva, M.A.; Kulyashov, M.A.; Kolpakov, F.A.; Akberdin, I.R. A Study of the Community Relationships Between Methanotrophs and Their Satellites Using Constraint-Based Modeling Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raajaraam, L.; Raman, K. Modeling Microbial Communities: Perspective and Challenges. ACS Synth. Biol. 2024, 13, 2260–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iguchi, H.; Yurimoto, H.; Sakai, Y. Interactions of Methylotrophs with Plants and Other Heterotrophic Bacteria. Microorganisms 2015, 3, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, A.B. Evaluation of Methanotrophic Activity and Growth in a Methanotrophic-Heterotrophic Co-Culture. Ph.D. Thesis, Chemical and Biological Engineering Department, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, M.; Hoefman, S.; Kerckhof, F.-M.; Boon, N.; De Vos, P.; De Baets, B.; Heylen, K.; Waegeman, W. Exploration and Prediction of Interactions between Methanotrophs and Heterotrophs. Res. Microbiol. 2013, 164, 1045–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chidambarampadmavathy, K.; Karthikeyan, O.P.; Huerlimann, R.; Maes, G.E.; Heimann, K. Response of Mixed Methanotrophic Consortia to Different Methane to Oxygen Ratios. Waste Manag. 2017, 61, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Beck, D.A.C.; Chistoserdova, L. Natural Selection in Synthetic Communities Highlights the Roles of Methylococcaceae and Methylophilaceae and Suggests Differential Roles for Alternative Methanol Dehydrogenases in Methane Consumption. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Chistoserdova, L. Communal Metabolism of Methane and the Rare Earth Element Switch. J. Bacteriol. 2017, 199, 00328-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Groom, J.; Zheng, Y.; Chistoserdova, L.; Huang, J. Synthetic Methane-Consuming Communities from a Natural Lake Sediment. mBio 2019, 10, e01072-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linton, J.; Drozd, J. Microbial Interactions and Communities in Biotechnology. In Microbial Interactions and Communities; Bull, A.T., Slater, J.H., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982; pp. 357–406. [Google Scholar]

- Pohlmann, A.; Fricke, W.F.; Reinecke, F.; Kusian, B.; Liesegang, H.; Cramm, R.; Eitinger, T.; Ewering, C.; Pötter, M.; Schwartz, E.; et al. Genome Sequence of the Bioplastic-Producing “Knallgas” Bacterium Ralstonia eutropha H16. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1257–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, Y.J.; Son, J.; Jo, S.Y.; Park, S.Y.; Yoo, J.I.; Baritugo, K.-A.; Na, J.G.; Choi, J.; Kim, H.T.; Joo, J.C.; et al. Chemoautotroph Cupriavidus necator as a Potential Game-Changer for Global Warming and Plastic Waste Problem: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 340, 125693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandamme, P. Taxonomy of the Genus Cupriavidus: A Tale of Lost and Found. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 2285–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brigham, C.J.; Gai, C.S.; Lu, J.; Speth, D.R.; Worden, R.M.; Sinskey, A.J. Engineering Ralstonia eutropha for Production of Isobutanol from CO2, H2, and O2. In Advanced Biofuels and Bioproducts; Lee, J.W., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1065–1090. ISBN 978-1-4614-3347-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Yu, Z.; Haroon, F.; Hernández, M.E.; Chistoserdova, L. Metagenomic Insight into Environmentally Challenged Methane-Fed Microbial Communities. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshkin, I.Y.; Beck, D.A.C.; Lamb, A.E.; Tchesnokova, V.; Benuska, G.; McTaggart, T.L.; Kalyuzhnaya, M.G.; Dedysh, S.N.; Lidstrom, M.E.; Chistoserdova, L. Methane-Fed Microbial Microcosms Show Differential Community Dynamics and Pinpoint Taxa Involved in Communal Response. ISME J. 2015, 9, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, D.A.C.; Kalyuzhnaya, M.G.; Malfatti, S.; Tringe, S.G.; Glavina Del Rio, T.; Ivanova, N.; Lidstrom, M.E.; Chistoserdova, L. A Metagenomic Insight into Freshwater Methane-Utilizing Communities and Evidence for Cooperation between the Methylococcaceae and the Methylophilaceae. PeerJ 2013, 1, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hršak, D.; Begonja, A. Possible Interactions within a Methanotrophic-Heterotrophic Groundwater Community Able To Transform Linear Alkylbenzenesulfonates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 4433–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, H.S.; Shrestha, B.K.; Han, J.W.; Groth, D.E.; Barphagha, I.K.; Rush, M.C.; Melanson, R.A.; Kim, B.S.; Ham, J.H. Diversities in Virulence, Antifungal Activity, Pigmentation and DNA Fingerprint among Strains of Burkholderia glumae. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos Solano, B.; Barriuso Maicas, J.; Pereyra De La Iglesia, M.T.; Domenech, J.; Gutiérrez Mañero, F.J. Systemic Disease Protection Elicited by Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Strains: Relationship Between Metabolic Responses, Systemic Disease Protection, and Biotic Elicitors. Phytopathology 2008, 98, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poindexter, J.S. Dimorphic Prosthecate Bacteria: The Genera Caulobacter, Asticcacaulis, Hyphomicrobium, Pedomicrobium, Hyphomonas and Thiodendron. In The Prokaryotes; Dworkin, M., Falkow, S., Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K.-H., Stackebrandt, E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 72–90. ISBN 978-0-387-25495-1. [Google Scholar]

- Eberspächer, J.; Lingens, F. The Genus Phenylobacterium. In The Prokaryotes; Dworkin, M., Falkow, S., Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K.-H., Stackebrandt, E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 250–256. ISBN 978-0-387-25495-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardet, J.-F.; Hugo, C.; Bruun, B. The Genera Chryseobacterium and Elizabethkingia. In The Prokaryotes; Dworkin, M., Falkow, S., Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K.-H., Stackebrandt, E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 638–676. ISBN 978-0-387-25497-5. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.-D.; Lv, P.-L.; McIlroy, S.J.; Wang, Z.; Dong, X.-L.; Kouris, A.; Lai, C.-Y.; Tyson, G.W.; Strous, M.; Zhao, H.-P. Methane-Dependent Selenate Reduction by a Bacterial Consortium. ISME J. 2021, 15, 3683–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Revathi, K.; Khanna, S. Biodegradation of Cellulosic and Lignocellulosic Waste by Pseudoxanthomonas Sp R-28. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 134, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.H.; Lee, H.J.; Jeon, C.O. Piscinibacter defluvii Sp. Nov., Isolated from a Sewage Treatment Plant, and Emended Description of the Genus Piscinibacter Stackebrandt et al. 2009. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 4839–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Li, H.; Zheng, W.; Guo, F. Phylogenomics of Rhodocyclales and Its Distribution in Wastewater Treatment Systems. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefman, S.; Van Der Ha, D.; Iguchi, H.; Yurimoto, H.; Sakai, Y.; Boon, N.; Vandamme, P.; Heylen, K.; De Vos, P. Methyloparacoccus murrellii Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a Methanotroph Isolated from Pond Water. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2100–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, M.; Guo, J. Methane-Driven Perchlorate Reduction by a Microbial Consortium. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 13370–13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Baek, J.I.; Lee, J.-Y.; Jeong, J.; Kim, H.; Lee, D.-H.; Kim, D.-M.; Lee, S.-G. Syntrophic Co-Culture of a Methanotroph and Heterotroph for the Efficient Conversion of Methane to Mevalonate. Metab. Eng. 2021, 67, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crumbley, A.M.; Garg, S.; Pan, J.L.; Gonzalez, R. A Synthetic Co-Culture for Bioproduction of Ammonia from Methane and Air. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 51, kuae044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, K.; He, Q.P.; Wang, J. A Novel Semi-Structured Kinetic Model of Methanotroph-Photoautotroph Cocultures for Biogas Conversion. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, C.; Abate, T.; Chianese, S.; Musmarra, D.; Muñoz, R. Assessing the Performance of Synthetic Co-Cultures during the Conversion of Methane into Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate). Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 476, 146646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.A.; Chrisler, W.B.; Beliaev, A.S.; Bernstein, H.C. A Flexible Microbial Co-Culture Platform for Simultaneous Utilization of Methane and Carbon Dioxide from Gas Feedstocks. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 228, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, A.; Nguyen, L.T.; Lee, E.Y. Methanotrophic and Heterotrophic Co-Cultures for the Polyhydroxybutyrate Production by Co-Utilizing C1 and C3 Gaseous Substrates. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 420, 132111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.; De Roy, K.; Thas, O.; De Neve, J.; Hoefman, S.; Vandamme, P.; Heylen, K.; Boon, N. The More, the Merrier: Heterotroph Richness Stimulates Methanotrophic Activity. ISME J. 2014, 8, 1945–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veraart, A.J.; Garbeva, P.; Van Beersum, F.; Ho, A.; Hordijk, C.A.; Meima-Franke, M.; Zweers, A.J.; Bodelier, P.L.E. Living Apart Together—Bacterial Volatiles Influence Methanotrophic Growth and Activity. ISME J. 2018, 12, 1163–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzo, V.; Pérez-Pantoja, D.; Nikel, P.I. Pseudomonas putida KT2440: The Long Journey of a Soil-Dweller to Become a Synthetic Biology Chassis. J. Bacteriol. 2024, 206, e00136-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belda, E.; Van Heck, R.G.A.; José Lopez-Sanchez, M.; Cruveiller, S.; Barbe, V.; Fraser, C.; Klenk, H.; Petersen, J.; Morgat, A.; Nikel, P.I.; et al. The Revisited Genome of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 Enlightens Its Value as a Robust Metabolic Chassis. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 3403–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, A.; Escapa, I.F.; Martínez, V.; Dinjaski, N.; Herencias, C.; De La Peña, F.; Tarazona, N.; Revelles, O. A Holistic View of Polyhydroxyalkanoate Metabolism in Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poblete-Castro, I.; Becker, J.; Dohnt, K.; Dos Santos, V.M.; Wittmann, C. Industrial Biotechnology of Pseudomonas putida and Related Species. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 93, 2279–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salusjärvi, L.; Ojala, L.; Peddinti, G.; Lienemann, M.; Jouhten, P.; Pitkänen, J.-P.; Toivari, M. Production of Biopolymer Precursors Beta-Alanine and L-Lactic Acid from CO2 with Metabolically Versatile Rhodococcus opacus DSM 43205. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 989481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, I.; Schlegel, H.G. Studies on a Gram-Positive Hydrogen Bacterium, Nocardia Opaca Strain 1b: II. Enzyme Formation and Regulation under the Influence of Hydrogen or Fructose as Growth Substrates. Archiv. Mikrobiol. 1973, 88, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggag, M.; Schlegel, H.G. Studies on a Gram-Positive Hydrogen Bacterium, Nocardia Opaca 1 b: III. Purification, Stability and Some Properties of the Soluble Hydrogen Dehydrogenase. Arch. Microbiol. 1974, 100, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatte, S.; Kroppenstedt, R.M.; Rainey, F.A. Rhodococcus opacus Sp. Nov., An Unusual Nutritionally Versatile Rhodococcus-Species. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1994, 17, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, C.; Abate, T.; Marcos, E.; Chianese, S.; Musmarra, D.; Muñoz, R. Exploring New Strategies for Optimizing the Production of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) from Methane and VFAs in Synthetic Cocultures and Mixed Methanotrophic Consortia. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 4690–4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerckhof, F.-M.; Sakarika, M.; Van Giel, M.; Muys, M.; Vermeir, P.; De Vrieze, J.; Vlaeminck, S.E.; Rabaey, K.; Boon, N. From Biogas and Hydrogen to Microbial Protein Through Co-Cultivation of Methane and Hydrogen Oxidizing Bacteria. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 733753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.M.; Laevens, S.; Lee, T.M.; Coenye, T.; De Vos, P.; Mergeay, M.; Vandamme, P. Ralstonia taiwanensis Sp. Nov., Isolated from Root Nodules of Mimosa Species and Sputum of a Cystic Fibrosis Patient. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2001, 51, 1729–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-M.; James, E.K.; Prescott, A.R.; Kierans, M.; Sprent, J.I. Nodulation of Mimosa spp. by the β-Proteobacterium Ralstonia taiwanensis. MPMI 2003, 16, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strittmatter, C.S.; Poehlein, A.; Himmelbach, A.; Daniel, R.; Steinbüchel, A. Medium-Chain-Length Fatty Acid Catabolism in Cupriavidus necator H16: Transcriptome Sequencing Reveals Differences from Long-Chain-Length Fatty Acid β-Oxidation and Involvement of Several Homologous Genes. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e01428-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amadou, C.; Pascal, G.; Mangenot, S.; Glew, M.; Bontemps, C.; Capela, D.; Carrère, S.; Cruveiller, S.; Dossat, C.; Lajus, A.; et al. Genome Sequence of the β-Rhizobium Cupriavidus taiwanensis and Comparative Genomics of Rhizobia. Genome Res. 2008, 18, 1472–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, D.; Céspedes-Bernal, N.; Vega, A.; Ledger, T.; González, B.; Poupin, M.J. Nitrogen-Modulated Effects of the Diazotrophic Bacterium Cupriavidus taiwanensis on the Non-Nodulating Plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Soil 2025, 506, 819–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, L.; Tian, K.; Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Prior, B.A.; Wang, Z. Metabolic Engineering of Escherichia coli: A Sustainable Industrial Platform for Bio-Based Chemical Production. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 1200–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.; Kahn, D. Genetic Regulation of Biological Nitrogen Fixation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, S.; Clomburg, J.M.; Gonzalez, R. A Modular Approach for High-Flux Lactic Acid Production from Methane in an Industrial Medium Using Engineered Methylomicrobium buryatense 5GB1. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 45, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentscheva, G.; Nikolova, K.; Panayotova, V.; Peycheva, K.; Makedonski, L.; Slavov, P.; Radusheva, P.; Petrova, P.; Yotkovska, I. Application of Arthrospira platensis for Medicinal Purposes and the Food Industry: A Review of the Literature. Life 2023, 13, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selão, T.T.; Włodarczyk, A.; Nixon, P.J.; Norling, B. Growth and Selection of the Cyanobacterium Synechococcus Sp. PCC 7002 Using Alternative Nitrogen and Phosphorus Sources. Metab. Eng. 2019, 54, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.G.; Baesman, S.M.; Carlström, C.I.; Coates, J.D.; Oremland, R.S. Methane Oxidation Linked to Chlorite Dismutation. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostan, J.; Sjöblom, B.; Maixner, F.; Mlynek, G.; Furtmüller, P.G.; Obinger, C.; Wagner, M.; Daims, H.; Djinović-Carugo, K. Structural and Functional Characterisation of the Chlorite Dismutase from the Nitrite-Oxidizing Bacterium “Candidatus Nitrospira defluvii”: Identification of a Catalytically Important Amino Acid Residue. J. Struct. Biol. 2010, 172, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlynek, G.; Sjöblom, B.; Kostan, J.; Füreder, S.; Maixner, F.; Gysel, K.; Furtmüller, P.G.; Obinger, C.; Wagner, M.; Daims, H.; et al. Unexpected Diversity of Chlorite Dismutases: A Catalytically Efficient Dimeric Enzyme from Nitrobacter winogradskyi. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 2408–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiya, H.; Ohnishi, K.; Maki, M.; Watanabe, N.; Murase, T. Clinical Characteristics of Ochrobactrum anthropi Bacteremia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 1330–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wutkowska, M.; Tláskal, V.; Bordel, S.; Stein, L.Y.; Nweze, J.A.; Daebeler, A. Leveraging Genome-Scale Metabolic Models to Understand Aerobic Methanotrophs. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulyashov, M.A.; Kolmykov, S.K.; Khlebodarova, T.M.; Akberdin, I.R. State-of the-Art Constraint-Based Modeling of Microbial Metabolism: From Basics to Context-Specific Models with a Focus on Methanotrophs. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, K.; Aikawa, S.; Kojima, Y.; Toya, Y.; Furusawa, C.; Kondo, A.; Shimizu, H. Construction of a Genome-Scale Metabolic Model of Arthrospira platensis NIES-39 and Metabolic Design for Cyanobacterial Bioproduction. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tec-Campos, D.; Zuñiga, C.; Passi, A.; Del Toro, J.; Tibocha-Bonilla, J.D.; Zepeda, A.; Betenbaugh, M.J.; Zengler, K. Modeling of Nitrogen Fixation and Polymer Production in the Heterotrophic Diazotroph Azotobacter vinelandii DJ. Metab. Eng. Commun. 2020, 11, e00132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleman, A.B.; Mus, F.; Peters, J.W. Metabolic Model of the Nitrogen-Fixing Obligate Aerobe Azotobacter vinelandii Predicts Its Adaptation to Oxygen Concentration and Metal Availability. mBio 2021, 12, e02593-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.M.; Kim, T.Y.; Lee, S.Y. Genome-Scale Reconstruction and in Silico Analysis of the Ralstonia eutropha H16 for Polyhydroxyalkanoate Synthesis, Lithoautotrophic Growth, and 2-Methyl Citric Acid Production. BMC Syst. Biol. 2011, 5, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, M.; Crang, N.; Janasch, M.; Hober, A.; Forsström, B.; Kimler, K.; Mattausch, A.; Chen, Q.; Asplund-Samuelsson, J.; Hudson, E.P. Protein Allocation and Utilization in the Versatile Chemolithoautotroph Cupriavidus necator. eLife 2021, 10, e69019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearcy, N.; Garavaglia, M.; Millat, T.; Gilbert, J.P.; Song, Y.; Hartman, H.; Woods, C.; Tomi-Andrino, C.; Reddy Bommareddy, R.; Cho, B.-K.; et al. A Genome-Scale Metabolic Model of Cupriavidus necator H16 Integrated with TraDIS and Transcriptomic Data Reveals Metabolic Insights for Biotechnological Applications. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, J.M.; Charusanti, P.; Aziz, R.K.; Lerman, J.A.; Premyodhin, N.; Orth, J.D.; Feist, A.M.; Palsson, B.Ø. Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstructions of Multiple Escherichia coli Strains Highlight Strain-Specific Adaptations to Nutritional Environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20338–20343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, J.M.; Koza, A.; Campodonico, M.A.; Machado, D.; Seoane, J.M.; Palsson, B.O.; Herrgård, M.J.; Feist, A.M. Multi-Omics Quantification of Species Variation of Escherichia coli Links Molecular Features with Strain Phenotypes. Cell Syst. 2016, 3, 238–251.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales, J.; Palsson, B.Ø.; Thiele, I. A Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstruction of Pseudomonas putida KT2440: I JN746 as a Cell Factory. BMC Syst. Biol. 2008, 2, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchałka, J.; Oberhardt, M.A.; Godinho, M.; Bielecka, A.; Regenhardt, D.; Timmis, K.N.; Papin, J.A.; Martins Dos Santos, V.A.P. Genome-Scale Reconstruction and Analysis of the Pseudomonas putida KT2440 Metabolic Network Facilitates Applications in Biotechnology. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008, 4, e1000210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberhardt, M.A.; Puchałka, J.; Martins Dos Santos, V.A.P.; Papin, J.A. Reconciliation of Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstructions for Comparative Systems Analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1001116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.B.; Kim, T.Y.; Park, J.M.; Lee, S.Y. In Silico Genome-scale Metabolic Analysis of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 for Polyhydroxyalkanoate Synthesis, Degradation of Aromatics and Anaerobic Survival. Biotechnol. J. 2010, 5, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Q.; Huang, T.; Li, P.; Hao, T.; Li, F.; Ma, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Chen, T.; Goryanin, I. Pathway-Consensus Approach to Metabolic Network Reconstruction for Pseudomonas putida KT2440 by Systematic Comparison of Published Models. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales, J.; Mueller, J.; Gudmundsson, S.; Canalejo, F.J.; Duque, E.; Monk, J.; Feist, A.M.; Ramos, J.L.; Niu, W.; Palsson, B.O. High-quality Genome-scale Metabolic Modelling of Pseudomonas putida Highlights Its Broad Metabolic Capabilities. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roell, G.W.; Schenk, C.; Anthony, W.E.; Carr, R.R.; Ponukumati, A.; Kim, J.; Akhmatskaya, E.; Foston, M.; Dantas, G.; Moon, T.S.; et al. A High-Quality Genome-Scale Model for Rhodococcus opacus Metabolism. ACS Synth. Biol. 2023, 12, 1632–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, S.A.; Palsson, B.Ø. Genome-Scale Reconstruction of the Metabolic Network in Staphylococcus aureus N315: An Initial Draft to the Two-Dimensional Annotation. BMC Microbiol. 2005, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, M.; Kümmel, A.; Ruinatscha, R.; Panke, S. In Silico Genome-scale Reconstruction and Validation of the Staphylococcus aureus Metabolic Network. Biotech. Bioeng. 2005, 92, 850–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seif, Y.; Monk, J.M.; Mih, N.; Tsunemoto, H.; Poudel, S.; Zuniga, C.; Broddrick, J.; Zengler, K.; Palsson, B.O. A Computational Knowledge-Base Elucidates the Response of Staphylococcus aureus to Different Media Types. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1006644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.J.; Reed, J.L. Identification of Functional Differences in Metabolic Networks Using Comparative Genomics and Constraint-Based Models. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.T.; Hill, E.A.; Kucek, L.A.; Konopka, A.E.; Beliaev, A.S.; Reed, J.L. Computational Evaluation of Synechococcus Sp. PCC 7002 Metabolism for Chemical Production. Biotechnol. J. 2013, 8, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, J.I.; Prasannan, C.B.; Joshi, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Wangikar, P.P. Metabolic Model of Synechococcus Sp. PCC 7002: Prediction of Flux Distribution and Network Modification for Enhanced Biofuel Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 213, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, X.; Kim, M.K.; Kumaraswamy, G.K.; Agarwal, A.; Lun, D.S.; Dismukes, G.C. Flux Balance Analysis of Photoautotrophic Metabolism: Uncovering New Biological Details of Subsystems Involved in Cyanobacterial Photosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Bioenerg. 2017, 1858, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Qian, J.; Wang, Y.; Ye, C. Current Status and Applications of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models of Oleaginous Microorganisms. Food Bioeng. 2024, 3, 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokic, M.; Hatzimanikatis, V.; Miskovic, L. Large-Scale Kinetic Metabolic Models of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 for Consistent Design of Metabolic Engineering Strategies. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morlino, M.S.; Serna García, R.; Savio, F.; Zampieri, G.; Morosinotto, T.; Treu, L.; Campanaro, S. Cupriavidus necator as a Platform for Polyhydroxyalkanoate Production: An Overview of Strains, Metabolism, and Modeling Approaches. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 69, 108264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, A.; Dräger, A. Curating and Comparing 114 Strain-Specific Genome-Scale Metabolic Models of Staphylococcus aureus. npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 2021, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, E.; Monk, J.M.; Aziz, R.K.; Fondi, M.; Nizet, V.; Palsson, B.Ø. Comparative Genome-Scale Modelling of Staphylococcus aureus Strains Identifies Strain-Specific Metabolic Capabilities Linked to Pathogenicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchel, F.; Rodriguez, N.; Swainston, N.; Wrzodek, C.; Czauderna, T.; Keller, R.; Mittag, F.; Schubert, M.; Glont, M.; Golebiewski, M.; et al. Path2Models: Large-Scale Generation of Computational Models from Biochemical Pathway Maps. BMC Syst. Biol. 2013, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Matsuura, Y.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological Systems Database as a Model of the Real World. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D672–D677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, R.; Billington, R.; Keseler, I.M.; Kothari, A.; Krummenacker, M.; Midford, P.E.; Ong, W.K.; Paley, S.; Subhraveti, P.; Karp, P.D. The MetaCyc Database of Metabolic Pathways and Enzymes—A 2019 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D445–D453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittig, U.; Rey, M.; Weidemann, A.; Kania, R.; Müller, W. SABIO-RK: An Updated Resource for Manually Curated Biochemical Reaction Kinetics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D656–D660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, D.; Andrejev, S.; Tramontano, M.; Patil, K.R. Fast Automated Reconstruction of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models for Microbial Species and Communities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 7542–7553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodia, H.; Mishra, V.; Nakrani, P.; Muddana, C.; Kedia, A.; Rana, S.; Sahasrabuddhe, D.; Wangikar, P.P. Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis of High Cell Density Fed-batch Culture of Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) with Mass Spectrometry-based Spent Media Analysis. Biotech. Bioeng. 2024, 121, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Pérez-Rivero, C.; Webb, C.; Theodoropoulos, C. Dynamic Metabolic Analysis of Cupriavidus necator DSM545 Producing Poly(3-Hydroxybutyric Acid) from Glycerol. Processes 2020, 8, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieven, C.; Beber, M.E.; Olivier, B.G.; Bergmann, F.T.; Ataman, M.; Babaei, P.; Bartell, J.A.; Blank, L.M.; Chauhan, S.; Correia, K.; et al. MEMOTE for Standardized Genome-Scale Metabolic Model Testing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, C.; Gibbons, S.M.; Resendis-Antonio, O. MICOM: Metagenome-Scale Modeling To Infer Metabolic Interactions in the Gut Microbiota. mSystems 2020, 5, 10.1128/msystems.00606-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, H.; Ushio, M.; Suzuki, K.; Abe, M.S.; Yamamichi, M.; Okazaki, Y.; Canarini, A.; Hayashi, I.; Fukushima, K.; Fukuda, S.; et al. Facilitative Interaction Networks in Experimental Microbial Community Dynamics. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1153952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, K.; He, Q.P.; Wang, J. Identifying Interspecies Interactions within a Model Methanotroph-Photoautotroph Coculture Using Semi-Structured and Structured Modeling. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, A.; Metivier, A.; Chu, F.; Laurens, L.M.; Beck, D.A.; Pienkos, P.T.; Lidstrom, M.E.; Kalyuzhnaya, M.G. Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstructions and Theoretical Investigation of Methane Conversion in Methylomicrobium buryatense Strain 5G (B1). Microb. Cell Factories 2015, 14, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieven, C.; Petersen, L.A.H.; Jørgensen, S.B.; Gernaey, K.V.; Herrgard, M.J.; Sonnenschein, N. A Genome-Scale Metabolic Model for Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) Suggests Reduced Efficiency Electron Transfer to the Particulate Methane Monooxygenase. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Le, T.; Daggumati, S.R.; Saha, R. Investigation of Microbial Community Interactions between Lake Washington Methanotrophs Using Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Krause, S.M.B.; Beck, D.A.C.; Chistoserdova, L. A Synthetic Ecology Perspective: How Well Does Behavior of Model Organisms in the Laboratory Predict Microbial Activities in Natural Habitats? Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, E.; Zimmermann, J.; Baldini, F.; Thiele, I.; Kaleta, C. BacArena: Individual-Based Metabolic Modeling of Heterogeneous Microbes in Complex Communities. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Approach | A Mechanistic Description of Processes at the Organism Level | Application to M+H * Communities |

|---|---|---|

| Data-driven | ||

| Co-occurrence network modeling | − | + |

| Time-series correlation | − | − |

| Causal inference models | − | − |

| Regression models | − | − |

| Mechanistic | ||

| Ecological models | ||

| Lotka–Volterra model | +/− (partly) | − |

| MacArthur’s model | +/− (partly) | − |

| Monod equation | +/− (partly) | + |

| Cell-level models | ||

| Agent-based modeling | + | − |

| GSM-based models | + | + |

| Integrative and multiscale modeling approaches | + | − |

| Methanotrophs | Satellites | Article |

|---|---|---|

| Methylococcus capsulatus Bath | Cupriavidus necator | [6] |

| Cupriavidus gilardii | ||

| Cupriavidus paucula | ||

| Brevibacillus agri | ||

| Brevibacillus formosus | ||

| Brevibacillus reuszeri | ||

| Brevibacillus choshiensis | ||

| Brevibacillus parabrevis | ||

| Brevibacillus brevis | ||

| Brevibacillus centrosporus | ||

| Brevibacillus borstelensis | ||

| Bacillus aneurinolyticus | ||

| Bacillus migulanus | ||

| Bacillus acidovorans | ||

| Bacillus thermoaerophilu | ||

| Bacillus laterosporus | ||

| Aneurinibacillus migulanus | ||

| Aneurinibacillus aneurinolyticus | ||

| Methylococcus sp. Concept-8 | Ochrobactrum intermedium C13 | [7] |

| Brevundimonas mediterranea N7 | ||

| Cupriavidus sp. S-6 | ||

| Ralstonia sp. MSB2004 | ||

| Cupriavidus gilardii CR3 | ||

| Chryseobacterium bernardetii H4638 | ||

| Brevibacillus brevis DZBY05 | ||

| Brevibacillus brevis DZBY10 | ||

| Brevibacillus fluminis CJ71 | ||

| Methylomonas sp. M5 | Cupriavidus taiwanensis LMG 19424 | [38] |

| Methylocystis sp. NLS7 | Pseudomonas chlororaphis | [39] |

| Methylosarcina fibrata DSM 13736 | Staphylococcus aureus R-23700 | [40] |

| Methylovulum miyakonense HT12 | Rhizobium sp. Rb122 | [8] |

| Methylosarcina | Chryseobacterium sp. JT03 | [41] |

| Methylobacter Methylomonas | Methylophilus methylotrophus Q8 | [42] |

| Methylotenera mobilis JLW8 | ||

| Methylotenera sp. G11 | ||

| Methylobacter tundripaludum | Methylotenera mobilis JLW8 | [43] |

| Methylotenera mobilis 13 | ||

| Methylosarcina | Methylophilus | [43] |

| Methylomonas sp. strain LW13 | Methylophilus methylotrophus Q8 | [44] |

| Acidovorax sp. 30s | ||

| Flavobacterium sp. 81 |

| Methanotrophs | Satellites | Article |

|---|---|---|

| Methylococcus capsulatus Bath | Dechloromonas agitata CKB | [64] |

| Escherichia coli SBA01 | [65] | |

| Methylotuvimicrobium buryatense 5GB1C | Azotobacter vinelandii M5I3 | [66] |

| Methylomicrobium buryatense 5GB1 | Arthrospira platensis NIES-39 | [67] |

| Methylocystis hirsuta CSC1 | Rhodococcus opacus DSM 43205 | [68] |

| Pseudomonas putida KT2440 | ||

| Methylocystis parvus OBBP | Rhodococcus opacus DSM 43205 | |

| Pseudomonas putida KT2440 | ||

| Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum 20z | Synechococcus PCC 7002 | [69] |

| Methylocystis sp. OK1 | Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) | [70] |

| Methylomonas spp. | Rhizobium radiobacter LMG 287 | [71] |

| Ochrobactrum anthropi LMG 2134 | ||

| Pseudomonas putida LMG 24210 | ||

| Escherichia coli LMG 2092T | ||

| Methylocystis parvus OBBP | Pseudomonas mandelii JR-1 | [72] |

| Methylobacter luteus 53v | Bacillus pumilus YXY-10 | |

| Bacillus simplex DUCC3713 | ||

| Exiguobacterium undae B111 | ||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia ATCC 13637 |

| Organism | Model Information | Article | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model ID | Genes | Reactions | Metabolites | ||

| A. platensis NIES-39 | NIES-39 | 620 | 746 | 673 | [99] |

| A. vinelandii DJ * | iDT1278 | 1278 | 2469 | 2003 | [100] |

| iAA1300 | 1300 | 2289 | 1958 | [101] | |

| C. necator H16 * | RehMBEL1391 | 1256 | 1391 | 1171 | [102] |

| RehMBEL1391—updated | 1345 | 1538 | 1172 | [103] | |

| iCN1361 | 1361 | 1292 | 1263 | [104] | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | iB21_1397 | 1397 | 2733 | 1943 | [105] |

| iECD_1391 | 1391 | 2731 | 1943 | ||

| iEC1356_Bl21DE3 | 1356 | 2740 | 1918 | [106] | |

| P. putida KT2440 | iJN746 | 746 | 950 | 911 | [107] |

| iJP815 | 815 | 877 | 888 | [108] | |

| iJP962 | 949 | 1066 | 980 | [109] | |

| PpuMBEL1071 | 900 | 1071 | 1044 | [110] | |

| PpuQY1140 | 1140 | 1171 | 1104 | [111] | |

| iJN1462 | 1462 | 2929 | 2155 | [112] | |

| R. opacus PD630 * | iGR1773 | 1773 | 3025 | 1956 | [113] |

| S. aureus USA300 str. JE2 * | iSB619 | 619 | 743 | 655 | [114] |

| iMH551 | 551 | 860 | 801 | [115] | |

| iYS854 | 886 | 1455 | 1335 | [116] | |

| Synechocystis sp. PCC 7002 | iSyp611 | 611 | 552 | 542 | [117] |

| iSyp708 | 708 | 646 | 581 | [118] | |

| iSyp728 | 728 | 742 | 696 | [119] | |

| iSyp821 | 821 | 792 | 777 | [120] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Esembaeva, M.A.; Melikhova, E.V.; Kachnov, V.A.; Kulyashov, M.A. From Single Organisms to Communities: Modeling Methanotrophs and Their Satellites. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010003

Esembaeva MA, Melikhova EV, Kachnov VA, Kulyashov MA. From Single Organisms to Communities: Modeling Methanotrophs and Their Satellites. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsembaeva, Maryam A., Ekaterina V. Melikhova, Vladislav A. Kachnov, and Mikhail A. Kulyashov. 2026. "From Single Organisms to Communities: Modeling Methanotrophs and Their Satellites" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010003

APA StyleEsembaeva, M. A., Melikhova, E. V., Kachnov, V. A., & Kulyashov, M. A. (2026). From Single Organisms to Communities: Modeling Methanotrophs and Their Satellites. Microorganisms, 14(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010003