Flavonoid-Rich Cyperus esculentus Extracts Disrupt Cellular and Metabolic Functions in Staphylococcus aureus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Extracting Compounds from Different Parts of C. esculentus

2.3. Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

2.4. Oxford Cup Test

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopic Observation

2.6. Determination of the Bacterial Growth Curve

2.7. Metabolomics Analysis

2.8. Analysis of the Main Bacteriostatic Components in the Extract of C. esculentus

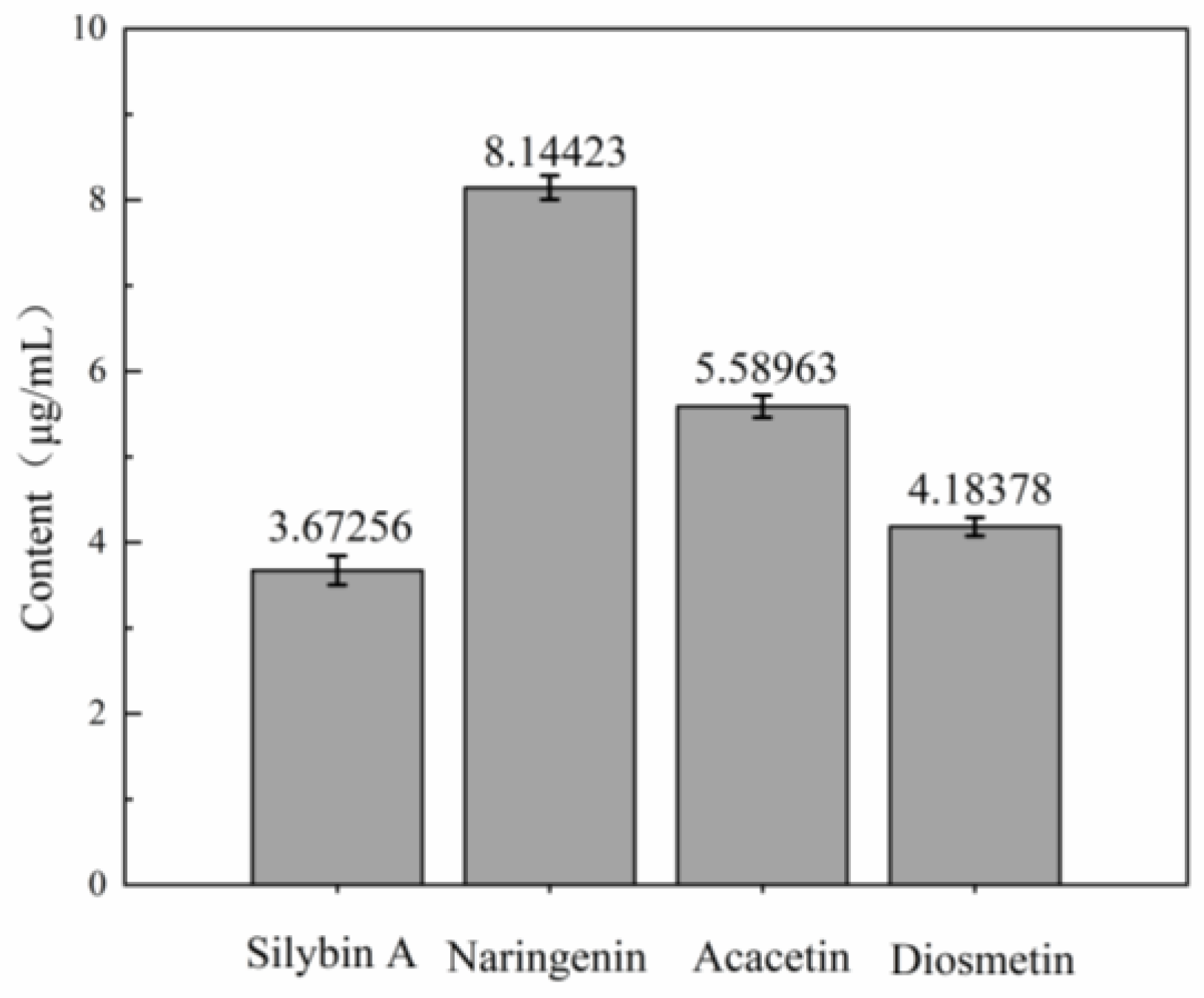

2.9. Quantitative Determination of Compounds

2.10. Statistics and Analysis

3. Results

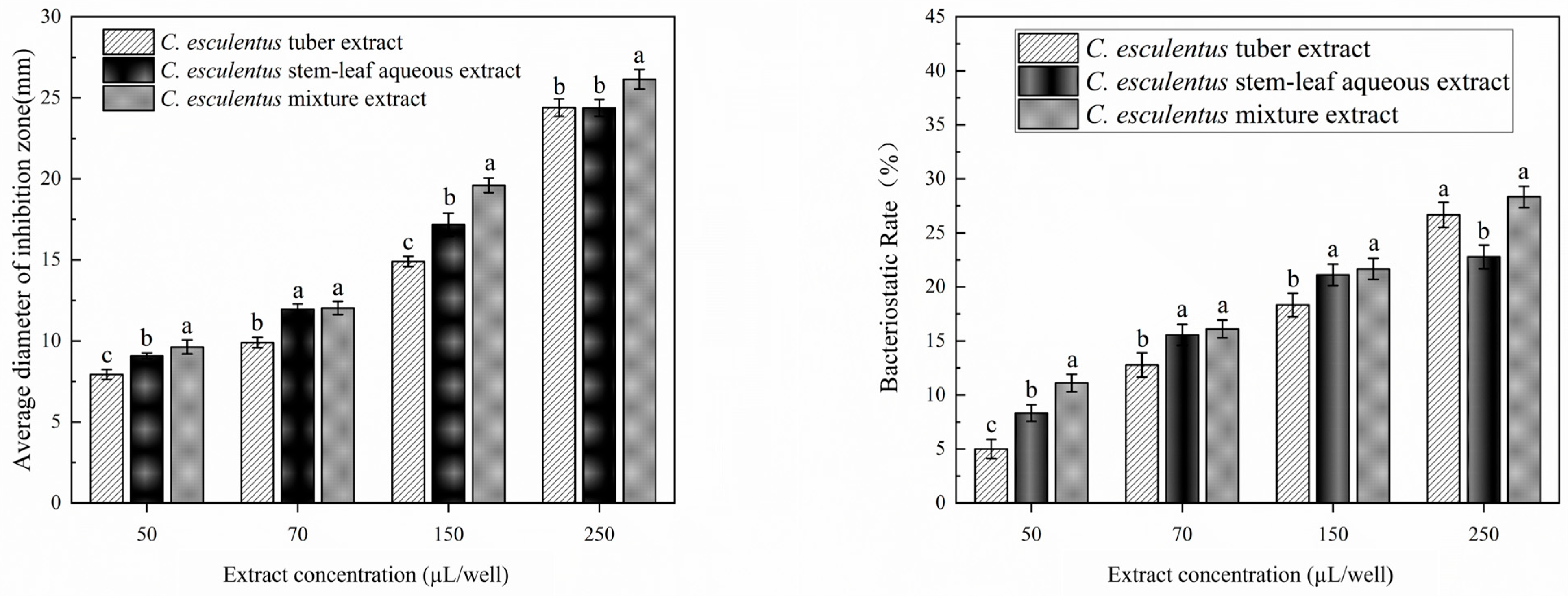

3.1. Inhibitory Zones of S. aureus by Extracts from Different Parts of C. esculentus

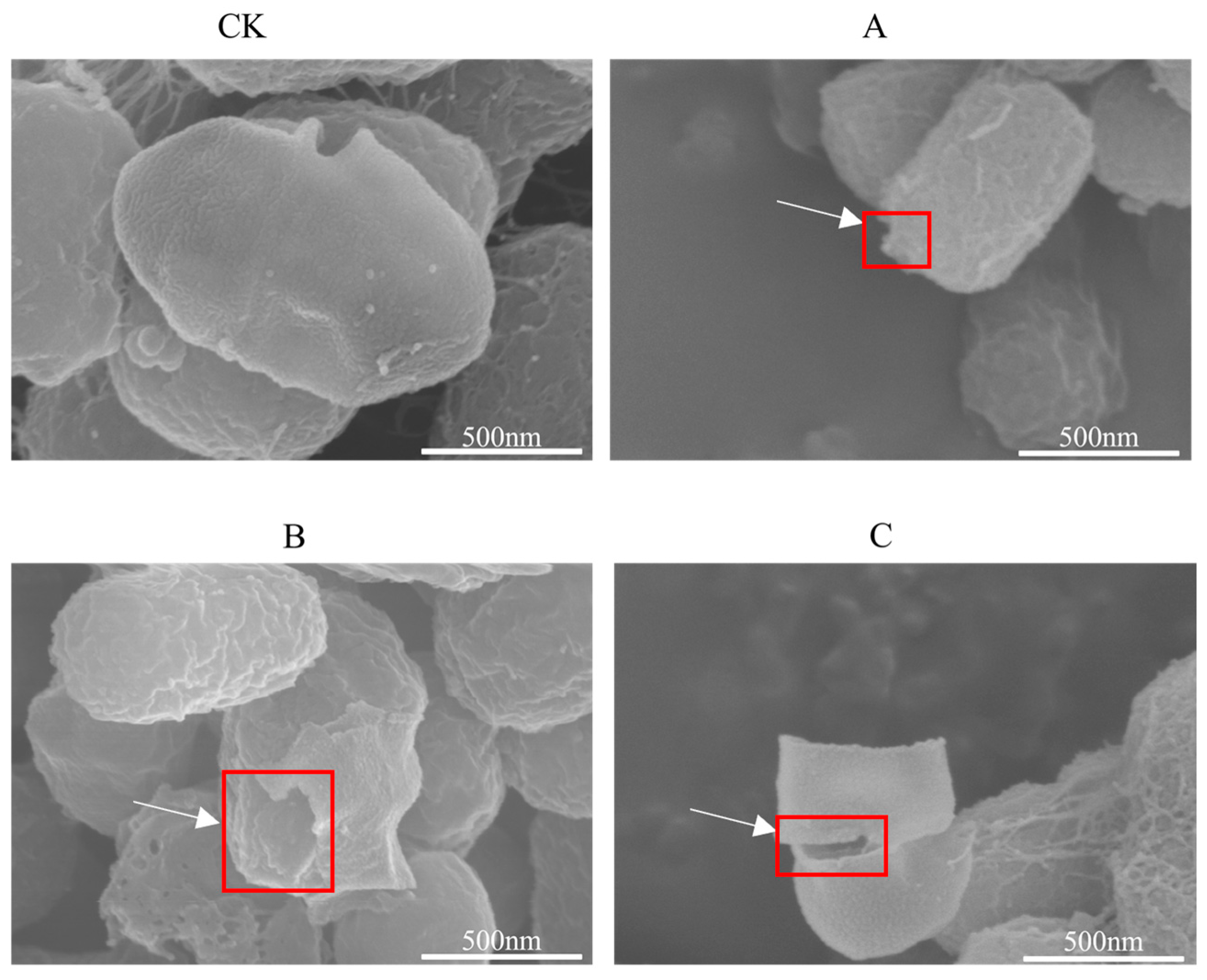

3.2. Observation of the Influence of Different Extracts of C. esculentus on S. aureus by Scanning Electron Microscope

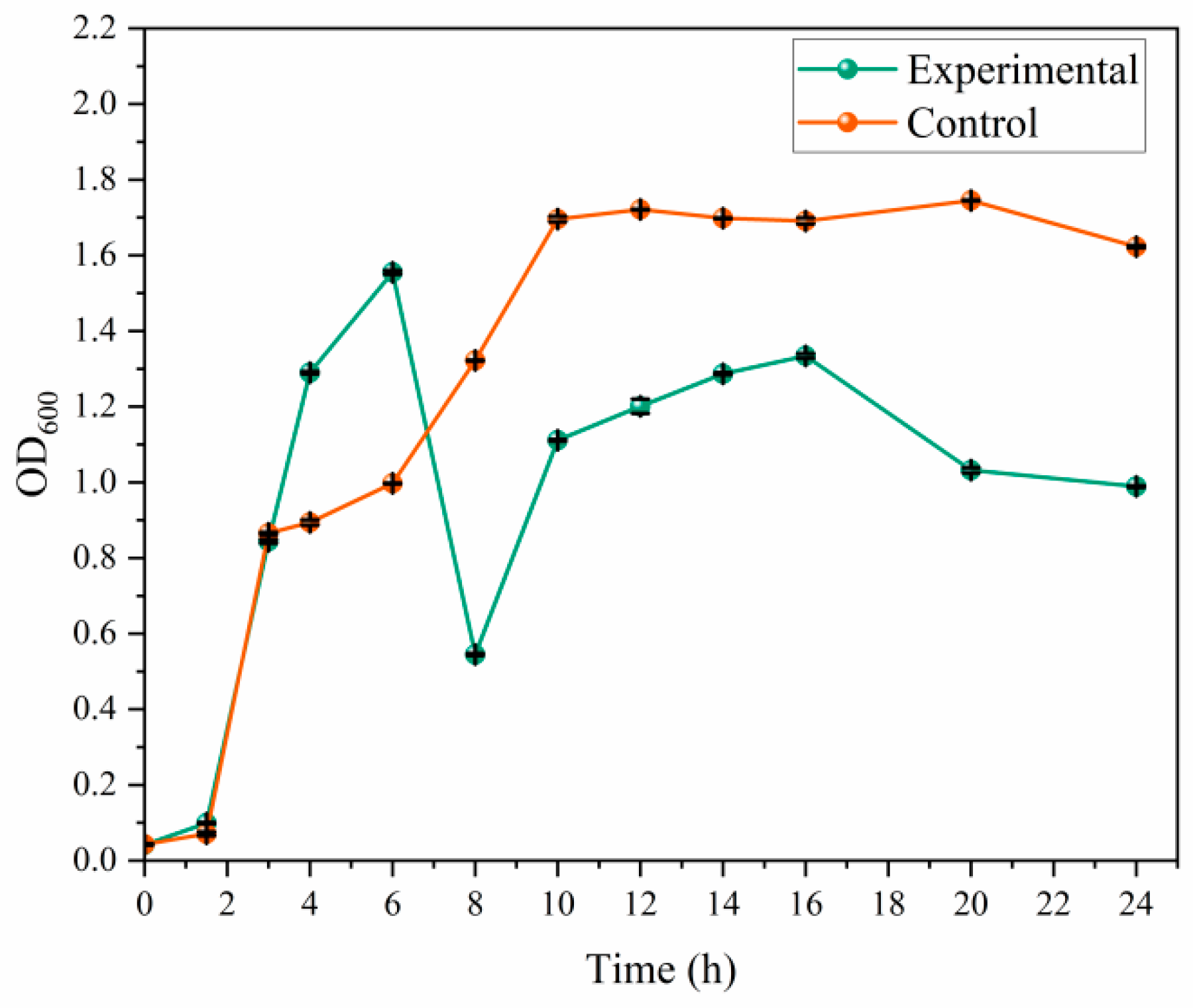

3.3. Growth Curve

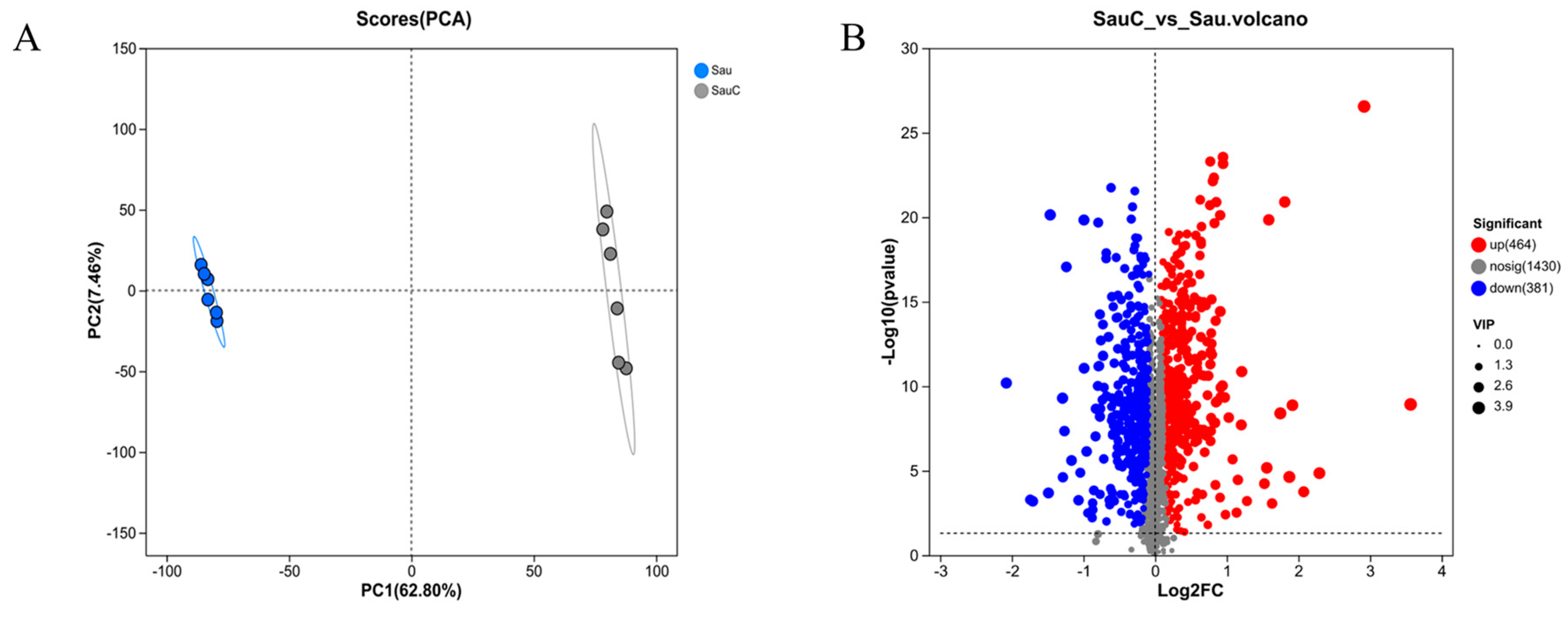

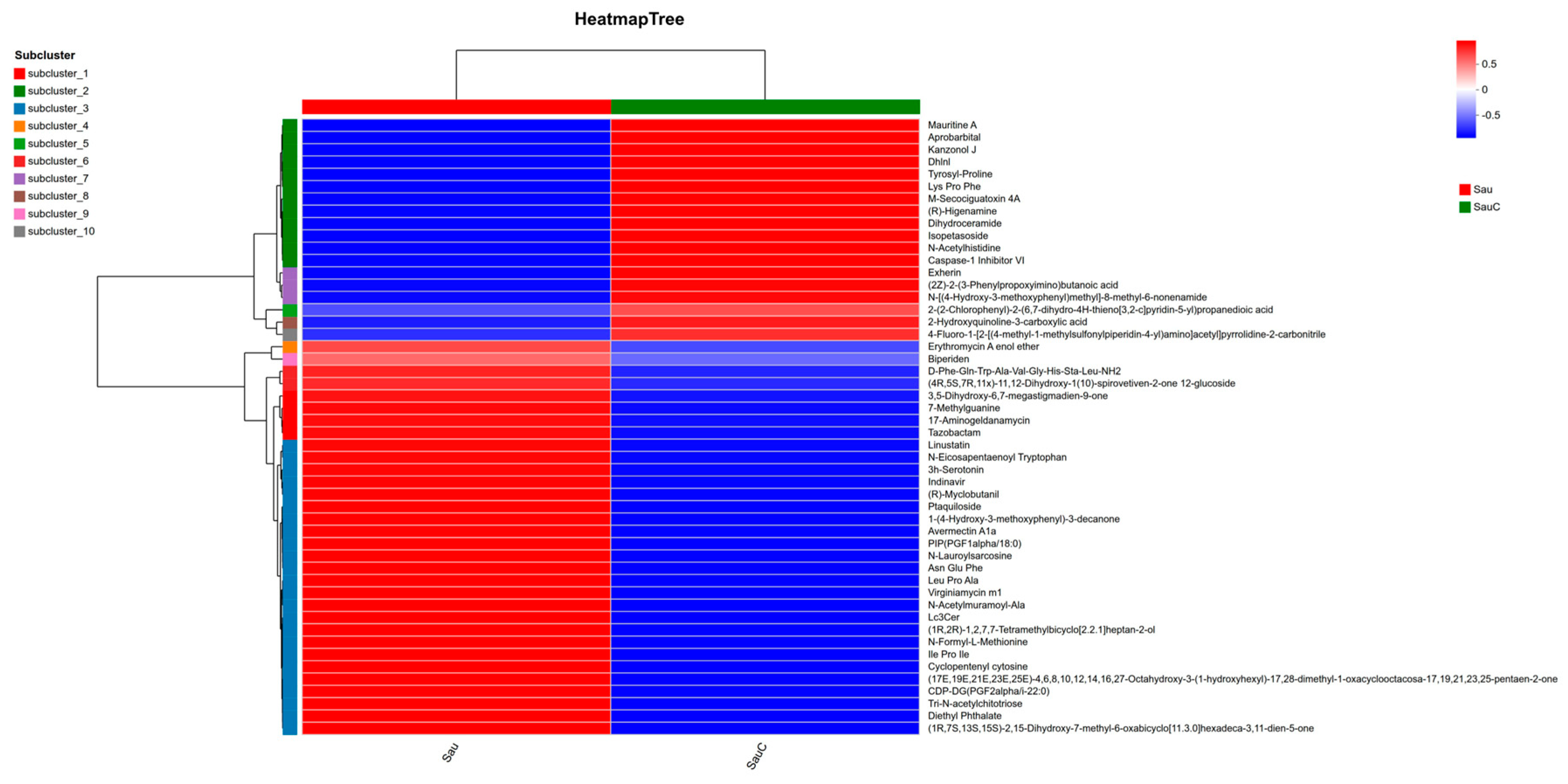

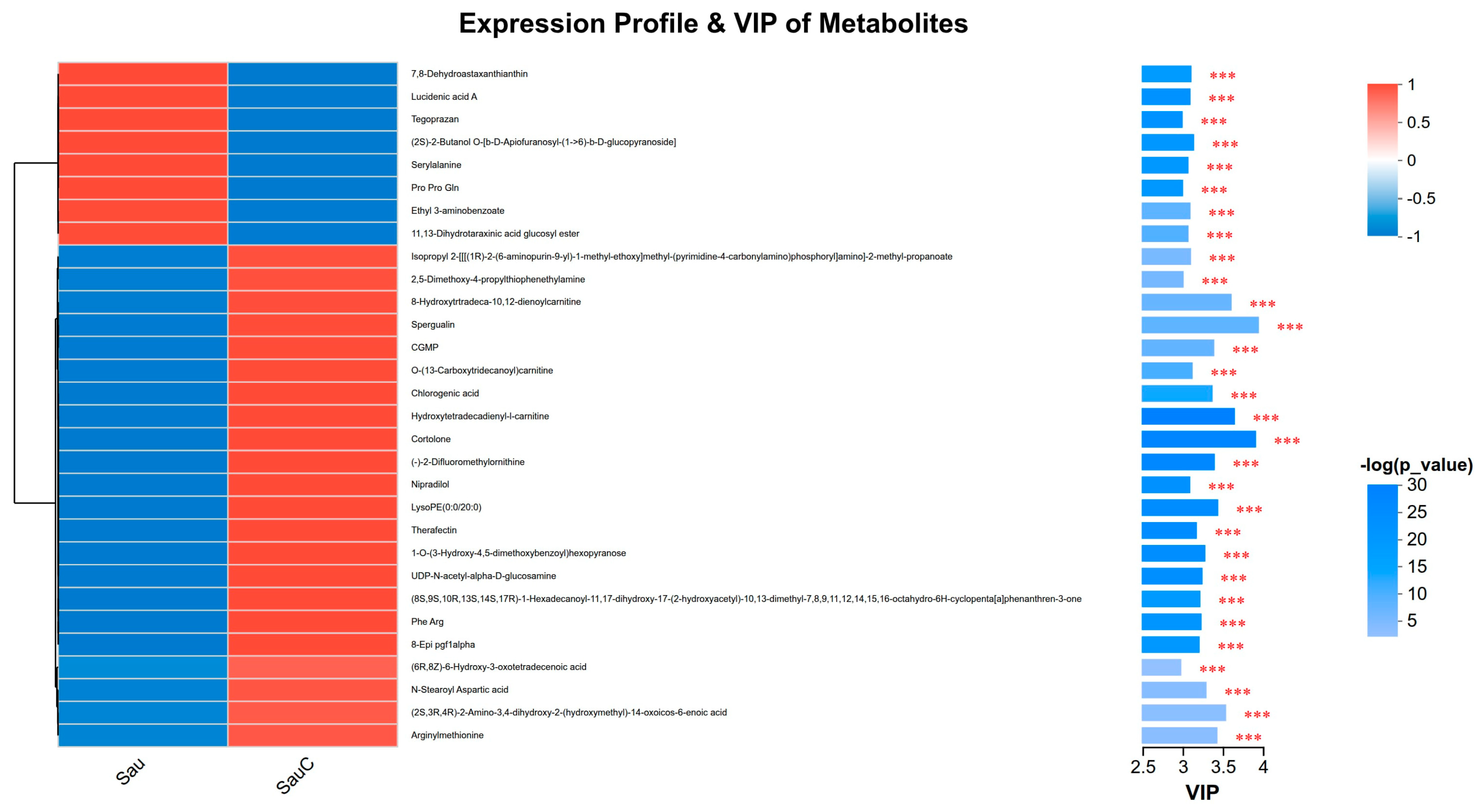

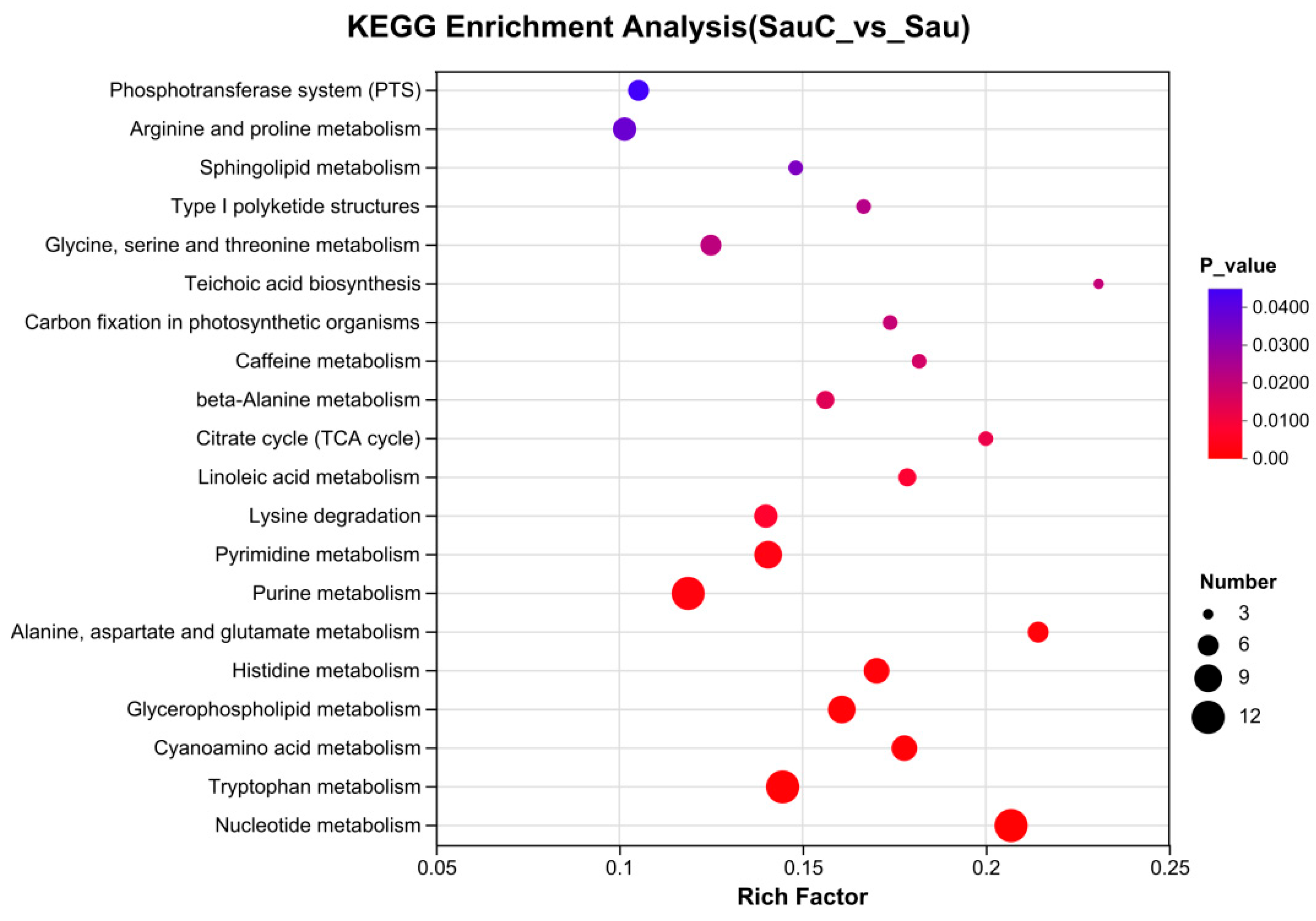

3.4. Analysis of the Effect of Adding the Extract of the Mixture of C. esculentus on the Metabolite of S. aureus

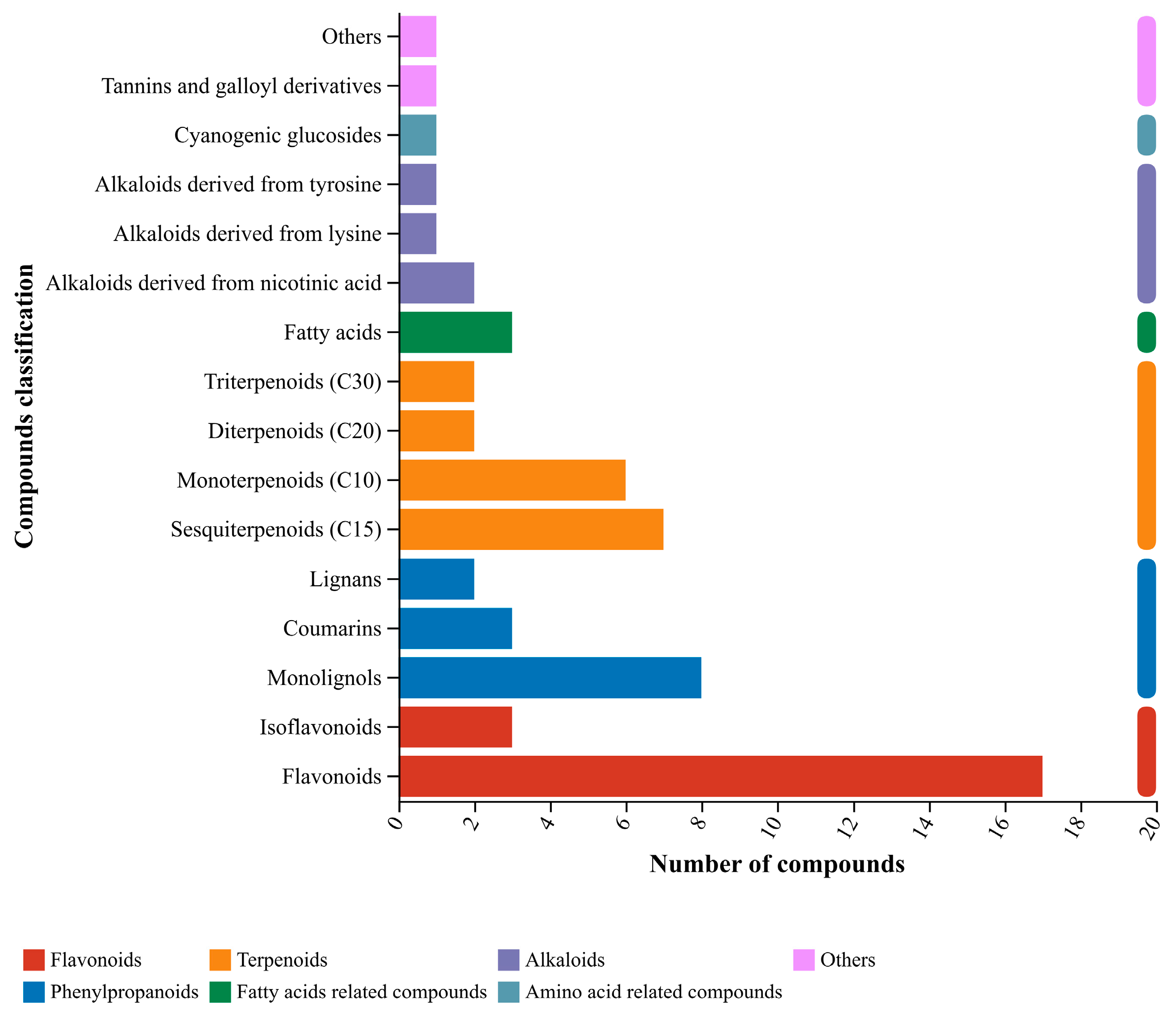

3.5. Main Antibacterial Compounds in C. esculentus Extract

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pahlevi, M.R.; Murakami, K.; Hiroshima, Y.; Murakami, A.; Fujii, H. pruR and PA0065 Genes Are Responsible for Decreasing Antibiotic Tolerance by Autoinducer Analog-1 (AIA-1) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasek-Nesselquist, E.; Lu, J.; Schneider, R.; Ma, Z.; Russo, V.; Mishra, S.; Pai, M.P.; Pata, J.D.; McDonough, K.A.; Malik, M. Insights Into the Evolution of Staphylococcus aureus Daptomycin Resistance from an in vitro Bioreactor Model. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, E.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Gu, S.; An, N.; Xin, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; An, Q.; Yi, J.; et al. Platelets Inhibit Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus by Inducing Hydroxyl Radical-Mediated Apoptosis-Like Cell Death. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02441-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.-Y.; Chung, C.-R.; Horng, J.-T.; Lu, J.-J.; Lee, T.-Y. Rapid Antibiotic Resistance Serial Prediction in Staphylococcus aureus Based on Large-Scale MALDI-TOF Data by Applying XGBoost in Multi-Label Learning. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 853775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Park, S.-D.; Uh, Y.; Lee, H. Multiplex Real-Time PCR Assay for Rapid Detection of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococci Directly from Positive Blood Cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 1911–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvauchelle, V.; Majdi, C.; Bénimélis, D.; Dunyach-Remy, C.; Meffre, P.; Benfodda, Z. Synthesis, Structure Elucidation, Antibacterial Activities, and Synergistic Effects of Novel Juglone and Naphthazarin Derivatives Against Clinical Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Strains. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 773981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, C.; Liu, T.; Li, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. Analyzing the Effect of Baking on the Flavor of Defatted Tiger Nut Flour by E-Tongue, E-Nose and HS-SPME-GC-MS. Foods 2022, 11, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Niu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, W.; Yang, C.; Yang, J.; Xing, G.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, J.; Slaski, J.; et al. Morpho-Agronomic and Biochemical Characterization of Accessions of Tiger Nut (Cyperus esculentus) Grown in the North Temperate Zone of China. Plants 2022, 11, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, S. Tiger nut (Cyperus esculentus L.) oil: A review of bioactive compounds, extraction technologies, potential hazards and applications. Food Chem. X 2023, 19, 100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, P.; Wei, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mu, Z. Cyperus (Cyperus esculentus L.): A Review of Its Compositions, Medical Efficacy, Antibacterial Activity and Allelopathic Potentials. Plants 2022, 11, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, N.; Ragavan, B. Phytochemical observation and antibacterial activity of Cyperus esculentus L. Anc. Sci. Life 2009, 28, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Gao, H.; Chen, X. A Review of Classification, Biosynthesis, Biological Activities and Potential Applications of Flavonoids. Molecules 2023, 28, 4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, L.; Figueiredo, P.; Souza, H.; Sousa, A.; Andrade-Júnior, F.; Barbosa-Filho, J.; Lima, E. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Activity of Myrtenol against Staphylococcus aureus. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros Cota, B.; Batista Carneiro de Oliveira, D.; Carla Borges, T.; Cristina Catto, A.; Valverde Serafim, C.; Rogelis Aquiles Rodrigues, A.; Kohlhoff, M.; Leomar Zani, C.; Assunção Andrade, A. Antifungal activity of extracts and purified saponins from the rhizomes of Chamaecostus cuspidatus against Candida and Trichophyton species. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 130, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, S.; Bhardwaj, V.; Mangal, V.; Kardile, H.; Dipta, B.; Kumar, A.; Singh, B.; Siddappa, S.; Sharma, A.K.; Dalamu; et al. Development of near homozygous lines for diploid hybrid TPS breeding in potatoes. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Dong, J.; Wang, Y.; Gong, X. RNA-seq analysis of antibacterial mechanism of Cinnamomum camphora essential oil against Escherichia coli. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellboudy, N.M.; Elwakil, B.H.; Shaaban, M.M.; Olama, Z.A. Cinnamon Oil-Loaded Nanoliposomes with Potent Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Activities. Molecules 2023, 28, 4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toh, S.C.; Lihan, S.; Bunya, S.R.; Leong, S.S. In vitro antimicrobial efficacy of Cassia alata (Linn.) leaves, stem, and root extracts against cellulitis causative agent Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, F.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Effects of Soil Tillage, Management Practices, and Mulching Film Application on Soil Health and Peanut Yield in a Continuous Cropping System. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 570924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubica, P.; Szopa, A.; Kokotkiewicz, A.; Miceli, N.; Taviano, M.F.; Maugeri, A.; Cirmi, S.; Synowiec, A.; Gniewosz, M.; Elansary, H.O.; et al. Production of Verbascoside, Isoverbascoside and Phenolic Acids in Callus, Suspension, and Bioreactor Cultures of Verbena officinalis and Biological Properties of Biomass Extracts. Molecules 2020, 25, 5609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Xia, L.; Zhou, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, P.; Qing, Z.; Zeng, J. Influence of different elicitors on BIA production in Macleaya cordata. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; She, P.; Xu, L.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Hussain, Z.; Wu, Y. Antimicrobial, Antibiofilm, and Anti-persister Activities of Penfluridol Against Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 727692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Q.; Tang, X.; Chen, X.; Ge, Y.; Ling, J. Light-Triggered Adhesive Silk-Based Film for Effective Photodynamic Antibacterial Therapy and Rapid Hemostasis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 820434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libis, V.; MacIntyre, L.W.; Mehmood, R.; Guerrero, L.; Ternei, M.A.; Antonovsky, N.; Burian, J.; Wang, Z.; Brady, S.F. Multiplexed mobilization and expression of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Xing, Y.; Ye, P.; Yu, H.; Meng, X.; Song, Y.; Wang, G.; Diao, Y. The antibacterial activity and mechanism of imidazole chloride ionic liquids on Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1109972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Sun, W.; Zhou, L.; Pei, S.; Zeng, H.; Cheng, Y.; Chai, S. The preparation of hybrid silicon quantum dots by one-step synthesis for tetracycline detection and antibacterial applications. Anal. Methods 2023, 15, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschoalini, B.R.; Nuñez, K.V.M.; Maffei, J.T.; Langoni, H.; Guimarães, F.F.; Gebara, C.; Freitas, N.E.; Dos Santos, M.V.; Fidelis, C.E.; Kappes, R.; et al. The Emergence of Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Characteristics in Enterococcus Species Isolated from Bovine Milk. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.W.; Liu, D.M.; Jing, L.; Xia, G.X.; Zhang, W.F.; Jiang, J.R.; Tang, J.B. Striatisporolide A, a butenolide metabolite from Athyrium multidentatum (Doll.) Ching, as a potential antibacterial agent. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-F.; Li, Q.-Y.; Wang, M.; Ma, S.-Q.; Zheng, Y.-F.; Li, Y.-Q.; Zhao, D.-L.; Zhang, C.-S. 2E,4E-Decadienoic Acid, a Novel Anti-Oomycete Agent from Coculture of Bacillus subtilis and Trichoderma asperellum. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0154222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.L.; van Venrooy, A.; Reed, A.K.; Wyderka, A.M.; García-López, V.; Alemany, L.B.; Oliver, A.; Tegos, G.P.; Tour, J.M. Hemithioindigo-Based Visible Light-Activated Molecular Machines Kill Bacteria by Oxidative Damage. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2203242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, G.; Zhu, Q.; Sun, B. Bioinformatics and Functional Assessment of Toxin-Antitoxin Systems in Staphylococcus aureus. Toxins 2018, 10, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Q.; Sun, C.; Shi, H.; Cai, S.; Xie, H.; Liu, F.; Zhu, J. Analysis of Related Metabolites Affecting Taste Values in Rice under Different Nitrogen Fertilizer Amounts and Planting Densities. Foods 2022, 11, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddaiah, C.; Kumar Bm, A.; Deepak, S.A.; Lateef, S.S.; Nagpal, S.; Rangappa, K.S.; Mohan, C.D.; Rangappa, S.; Kumar S, M.; Sharma, M.; et al. Metabolite Profiling of Alangium salviifolium Bark Using Advanced LC/MS and GC/Q-TOFTechnology. Cells 2020, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.; Yeom, J.; Ko, K.; Park, W.; Park, S. AFM probing the mechanism of synergistic effects of the green tea polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) with cefotaxime against extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Ahirwal, L.; Bajpai, V.K.; Huh, Y.S.; Han, Y.K. Growth Inhibitory Effects of Adhatoda vasica and Its Potential at Reducing Listeria monocytogenes in Chicken Meat. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1260, Erratum in Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1636. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Graham, J.; Zhai, T.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Z. Discovery of MurA Inhibitors as Novel Antimicrobials through an Integrated Computational and Experimental Approach. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, Y.S.; Shankarapillai, R.; Vivekanandan, G.; Shetty, R.M.; Reddy, C.S.; Reddy, H.; Mangalekar, S.B. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Guava Extract as an Antimicrobial Agent on Periodontal Pathogens. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2018, 19, 690–697. [Google Scholar]

- Montso, P.K.; Mnisi, C.M.; Ayangbenro, A.S. Caecal microbial communities, functional diversity, and metabolic pathways in Ross 308 broiler chickens fed with diets containing different levels of Marama (Tylosema esculentum) bean meal. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1009945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kani, A.N.; Dovi, E.; Aryee, A.A.; Han, R.; Qu, L. Efficient removal of 2,4-D from solution using a novel antibacterial adsorbent based on tiger nut residues: Adsorption and antibacterial study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 64177–64191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belmadani, N.; Kassous, W.; Keddar, K.; Amtout, L.; Hamed, D.; Douma-Bouthiba, Z.; Costache, V.; Gérard, P.; Ziar, H. Functional Cyperus esculentus L. Cookies Enriched with the Probiotic Strain Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus SL42. Foods 2024, 13, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assimon, V.A.; Shao, H.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S.; Gestwicki, J.E. Concise Synthesis of Spergualin-Inspired Molecules with Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic Activity. MedChemComm 2015, 6, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umezawa, H.; Kondo, S.; Iinuma, H.; Kunimoto, S.; Ikeda, Y.; Iwasawa, H.; Ikeda, D.; Takeuchi, T. Structure of an antitumor antibiotic, spergualin. J. Antibiot. 1981, 34, 1622–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xu, Y.; Liang, X.; Hyun, C.G. Isolation, Characterization, Genome Annotation, and Evaluation of Hyaluronidase Inhibitory Activity in Secondary Metabolites of Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 41: A Comprehensive Analysis through Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.; Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Zheng, L.; Yue, L.; Fan, S.; Tao, G. Dynamic high pressure microfluidization-assisted extraction and bioactivities of Cyperus esculentus (C. esculentus L.) leaves flavonoids. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, P.A.; Omobolanle, L.A.; Hamid, B.; Fayokemi, R.A.; Perveen, K.; Bukhari, N.A.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Mastinu, A. Evaluation of destruction of bacterial membrane structure associated with anti-quorum sensing and ant-diabetic activity of Cyperus esculentus extract. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; He, C.; Yang, H.; Shu, W.; Liu, Q. Integrative omics analysis reveals insights into small colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus induced by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuchscherr, L.; Löffler, B.; Proctor, R.A. Persistence of Staphylococcus aureus: Multiple Metabolic Pathways Impact the Expression of Virulence Factors in Small-Colony Variants (SCVs). Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment | MIC (μg/mL) | Interpretive Category |

|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin | ≤2 | Susceptible |

| Solvent | ≥32 | Resistant |

| C. esculentus mixture extract | 8 | Intermediate |

| Name | Mode | Formula | HMDB Superclass | Compound Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acacetin | Positive ion | C16H12O5 | Phenylpropanoids and polyketides | Flavonoids |

| Naringenin | Positive ion | C15H12O5 | Phenylpropanoids and polyketides | Flavonoids |

| Diosmetin | Positive ion | C16H12O6 | Phenylpropanoids and polyketides | Flavonoids |

| Silybin A | Negative ions | C25H22O10 | Phenylpropanoids and polyketides | Flavonoids |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Q.; Kang, X.; Gao, H. Flavonoid-Rich Cyperus esculentus Extracts Disrupt Cellular and Metabolic Functions in Staphylococcus aureus. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010260

Zhang Y, Ma Z, Wang X, Jiang Q, Kang X, Gao H. Flavonoid-Rich Cyperus esculentus Extracts Disrupt Cellular and Metabolic Functions in Staphylococcus aureus. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):260. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010260

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yaning, Zhengdong Ma, Xuzhe Wang, Qilong Jiang, Xue Kang, and Hongmei Gao. 2026. "Flavonoid-Rich Cyperus esculentus Extracts Disrupt Cellular and Metabolic Functions in Staphylococcus aureus" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010260

APA StyleZhang, Y., Ma, Z., Wang, X., Jiang, Q., Kang, X., & Gao, H. (2026). Flavonoid-Rich Cyperus esculentus Extracts Disrupt Cellular and Metabolic Functions in Staphylococcus aureus. Microorganisms, 14(1), 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010260