Diversity Analysis of Fecal Microbiota in Goats Driven by White Blood Cell Count

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Ethics

2.2. Experimental Design, Animals, and Diet

2.3. Fecal Sample Collection

2.4. Blood Sample Analysis

2.5. Fecal Microbiota Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Differences in Hematological Parameters Among Goat Groups Defined by Initial WBC Levels

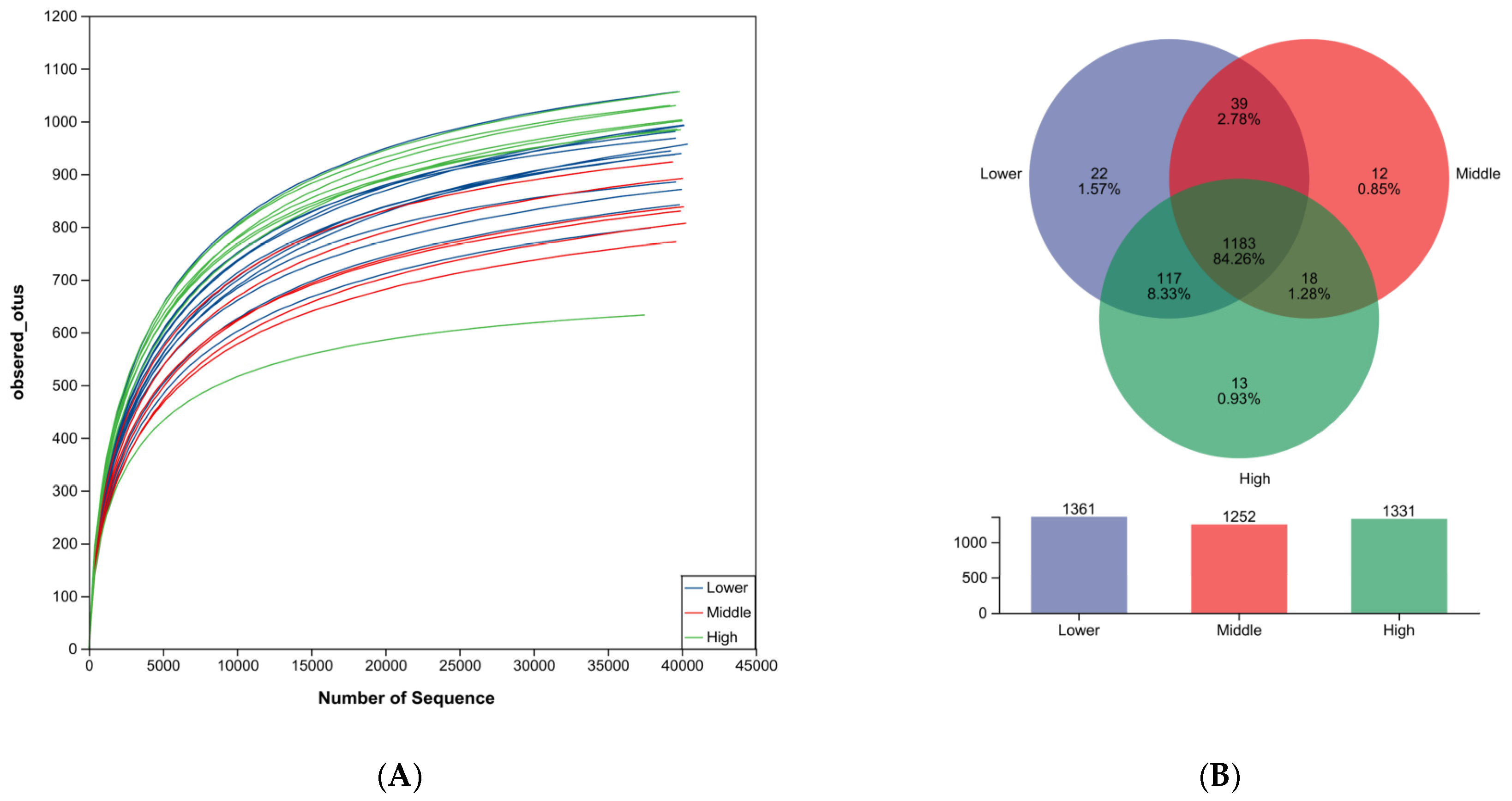

3.2. Sequencing Data

3.3. OUT Abundance Analysis

3.4. Community-Composition Analysis

3.5. LEfSe Analysis

3.6. Strong Correlations Between WBC Levels and Specific Microbial Groups

3.6.1. Correlation of WBC Levels with Microbiota

3.6.2. Correlation of Hematological Parameters with Microbiota

3.6.3. Indicators Without Statistical Significance

3.6.4. Indicators with Strong and Significant Correlation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, L.; Li, J.; Ma, N.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Yin, C.; Luo, J.; Liu, N.; Jia, Z.; Fu, C. Animal genetic resources in China: Sheep and goats. In China National Commission of Animal Genetic Resources; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; Volume 51, p. 151. ISBN 978-7-109-15881-8. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Wang, K.; Liu, H.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, H.; Han, J. Research Progress on Genetics and Breeding in Leizhou Goat. Chin. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 60, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, K.; Chen, A.; Peng, W.; Liu, H.; Han, J.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, Q. Effect of nano-selenium on growth performance and blood parameters of Leizhou goats barn-feeding in summer. Feed Res. 2024, 48, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Dong, S.; Lv, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, B.; Guo, Y.; Deng, M.; Liu, D.; Liu, G. Screening of SNP loci related to leg length trait in Leizhou goats based on whole-genome resequencing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalewska, M.; Jarczak, J.; Czopowicz, M.; Mickiewicz, M.; Kaba, J.; Bagnicka, E. Small ruminant lentivirus-infected dairy goats’ metabolic blood profile in different stages of lactation. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep. 2023, 41, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibova, V.B.; Pozovnikova, M.V. The value of blood’s biochemical parameters in early lactation in predicting the reproductive ability of dairy goats in the subsequent breeding season. Russ. Agric. Sci. 2022, 48, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoung, H.; Shin, I.; Kim, Y.; Cho, J.H.; Park, K.I.; Kim, Y.; Ahn, J.; Nam, J.; Kim, K.; Kang, Y.; et al. Mixed supplementation of dietary inorganic and organic selenium modulated systemic health parameters and fecal microbiota in weaned pigs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1531336. [Google Scholar]

- Magro, S.; De Marchi, M.; Cassandro, M.; Finocchiaro, R.; Fabris, A.; Marusi, M.; Costa, A. Blood parameters predicted from milk spectra are candidate indicator traits of hyperketonemia—A retrospective study in the Italian Holstein population. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 2683–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.L.; Allison, R.W. Evaluation of the ruminant complete blood cell count. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2007, 23, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, A.E.; El-Maghraby, M.M.; Elbialy, Z.I.; Al Wakeel, R.A.; Almadaly, E.A.; Shukry, M.; El-Badawy, A.A.; Zaghloul, H.K.; Assar, D.H. Mitigation of endogenous oxidative stress and improving growth, hemato-biochemical parameters, and reproductive performance of Zaraibi goat bucks by dietary supplementation with Chlorella vulgaris or/and vitamin C. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 55, 267. [Google Scholar]

- Arfuso, F.; Fazio, F.; Rizzo, M.; Marafioti, S.; Zanghì, E.; Piccione, G. Factors affecting the hematological parameters in different goat breeds from Italy. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2016, 16, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuseppe, P.; Giovanni, C. Biological rhythm in livestock. J. Vet. Sci. 2002, 3, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, P.P.; Strzelec, B. Elevated leukocyte count as a harbinger of systemic inflammation, disease progression, and poor prognosis: A review. Folia Morphol. 2018, 77, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Frenette, P.S. Cross talk between neutrophils and the microbiota. Blood 2019, 133, 2168–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremonesi, P.; Capoferri, R.; Pisoni, G.; Del Corvo, M.; Strozzi, F.; Rupp, R.; Caillat, H.; Modesto, P.; Moroni, P.; Williams, J.L.; et al. Response of the goat mammary gland to infection with staphylococcus aureus revealed by gene expression profiling in milk somatic and white blood cells. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkawi, M.; Soukouti, A. Reference values of essential haematological parameters in Damascus does and bucks throughout the year. Arch. Zootech. 2024, 27, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jia, R.; Zhao, Y.; Su, N.; Fan, G.; Yuan, C.; Zhao, C.; Hu, X. Associations of ruminal microbiota with susceptibility to subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy goats. Microb. Pathog. 2025, 206, 107727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffas, A.; Burgos Da Silva, M.; Slingerland, A.E.; Lazrak, A.; Bare, C.J.; Holman, C.D.; Docampo, M.D.; Shono, Y.; Durham, B.; Pickard, A.J.; et al. Nutritional support from the intestinal microbiota improves hematopoietic reconstitution after bone marrow transplantation in mice. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, M.L.; Schürch, C.M.; Saito, Y.; Geuking, M.B.; Li, H.; Cuenca, M.; Kovtonyuk, L.V.; Mccoy, K.D.; Hapfelmeier, S.; Ochsenbein, A.F.; et al. Microbiota-derived compounds drive steady-state granulopoiesis via MyD88/TICAM signaling. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 5273–5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, A.; Yáñez, A.; Price, J.G.; Chow, A.; Merad, M.; Goodridge, H.S.; Mazmanian, S.K. Gut microbiota promote hematopoiesis to control bacterial infection. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamura, C.; Bouladoux, N.; Belkaid, Y.; Sher, A.; Jankovic, D. Sensing of the microbiota by Nod1 in mesenchymal stromal cells regulates murine hematopoiesis. Blood 2017, 129, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenburg, J.L.; Bäckhed, F. Diet–microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature 2016, 535, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.V.; Littman, D.R.; Macpherson, A.J. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science 2012, 336, 1268–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkaid, Y.; Bouladoux, N.; Hand, T.W. Effector and memory T cell responses to commensal bacteria. Trends Immunol. 2013, 34, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hand, T.W.; Vujkovic-Cvijin, I.; Ridaura, V.K.; Belkaid, Y. Linking the microbiota, chronic disease, and the immune system. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 27, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatino, A.; Regolisti, G.; Brusasco, I.; Cabassi, A.; Morabito, S.; Fiaccadori, E. Alterations of intestinal barrier and microbiota in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial, Transp. 2015, 30, 924–933. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Q.; Jin, G.; Wang, G.; Liu, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, B.; Cao, H. Current sampling methods for gut microbiota: A call for more precise devices. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouhy, F.; Deane, J.; Rea, M.C.; O’Sullivan, Ó.; Ross, R.P.; O’Callaghan, G.; Plant, B.J.; Stanton, C. The effects of freezing on faecal microbiota as determined using MiSeq sequencing and culture-based investigations. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119355. [Google Scholar]

- NY/T 816-2021; Nutrient Requirements of Meat-Type Sheep and Goat. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Miranda-De La Lama, G.C.; Mattiello, S. The importance of social behaviour for goat welfare in livestock farming. Small Rumin. Res. 2010, 90, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Yan, B.; Zhou, H.; Wu, Q.; Wang, K.; Yang, Y.; Peng, W.; Liu, H.; Ji, C.; Zhang, X.; et al. Time-budget of housed goats reared for meat production: Effects of stocking density on natural behaviour expression and welfare. Agriculture 2026, 16, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Younis, F.E.; Basyony, M.A.; Abouelezz, S.S.; Elbolkiny, Y.E.; Elshehry, S.T. Comparative study of heat stress effect on thermoregulatory and physiological responses of Baladi and Shami goats in Egypt. J. Anim. Poult. Prod. 2018, 9, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aleena, J.; Sejian, V.; Bagath, M.; Krishnan, G.; Beena, V.; Bhatta, R. Resilience of three indigenous goat breeds to heat stress based on phenotypic traits and PBMC HSP70 expression. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 1995–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; AOAC: Arlington, VA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Peng, W.; Hu, H.; Hou, G.; Zhou, H. Effect of Long-term Heat Stress on Blood Biochemical and Physiological Index, Hormone, and Semen Quality of Goat. J. Domest. Anim. Ecol. 2018, 39, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Mao, K.; Peng, W.; Degen, A.; Zuo, G.; Yang, Y.; Han, J.; Wu, Q.; Wang, K.; Jiang, Q.; et al. Nano-selenium reduces concentrations of fecal minerals by altering bacteria composition in feedlot goats. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, G.; Jiang, Y.; He, M.; Wang, C.; Gu, Y.; Ling, S.; Cao, S.; Wen, Y.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Skin mycobiota of the captive giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) and the distribution of opportunistic dermatomycosis-associated fungi in different seasons. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 708077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torok, V.A.; Allison, G.E.; Percy, N.J.; Ophel-Keller, K.; Hughes, R.J. Influence of antimicrobial feed additives on broiler commensal posthatch gut microbiota development and performance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3380–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, G.; Yang, C.; He, M.; Wang, C.; Gu, Y.; Ling, S.; Cao, S.; Yan, Q.; Han, X.; et al. Skin microbiota of the captive giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) and the distribution of opportunistic skin disease-associated bacteria in different seasons. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 666486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Meng, D.; Liu, J. The gut microbiota of wild wintering great bustard (Otis tarda Dybowskii): Survey data from two consecutive years. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Luo, X.; Ma, X.; Zhang, D.; Yan, X.; Deng, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; An, J.; Fan, X.; et al. Contrasting vaginal bacterial communities between estrus and non-estrus of giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 707548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conteville, L.C.; Da Silva, J.V.; Andrade, B.G.N.; Cardoso, T.F.; Bruscadin, J.J.; de Oliveira, P.S.N.; Mourão, G.B.; Coutinho, L.L.; Palhares, J.C.P.; Berndt, A.; et al. Rumen and fecal microbiomes are related to diet and production traits in Bos indicus beef cattle. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1282851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, Z.; Hou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z. High-production dairy cattle exhibit different rumen and fecal bacterial community and rumen metabolite profile than low-production cattle. MicrobiologyOpen 2019, 8, e00673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Shui, Y.; Deng, M.; Guo, Y.; Sun, B.; Liu, G.; Liu, D.; Li, Y. Effects of different dietary energy levels on growth performance, meat quality and nutritional composition, rumen fermentation parameters, and rumen microbiota of fattening angus steers. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1378073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, A.; Stewart, L.; Blanchard, J.; Leschine, S. Untangling the genetic basis of fibrolytic specialization by Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae in diverse gut communities. Diversity 2013, 5, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, G.; Manwani, D.; Mortha, A.; Xu, C.; Faith, J.J.; Burk, R.D.; Kunisaki, Y.; Jang, J.; Scheiermann, C.; et al. Neutrophil ageing is regulated by the microbiome. Nature 2015, 525, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. The microbiome-gut-brain axis in health and disease. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 46, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaisas, S.; Maher, J.; Kanthasamy, A. Gut microbiome in health and disease: Linking the microbiome–gut–brain axis and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of systemic and neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 158, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Lkhagva, E.; Jung, S.; Kim, H.; Chung, H.; Hong, S.; Kolla, J.N. Fecal microbiome does not represent whole gut microbiome. Cell Microbiol. 2023, 2023, 6868417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Parameter | Content (g·kg−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Feed ingredients | Corn | 300.00 |

| Peanut hay | 375.00 | |

| Soybean meal | 60.00 | |

| Distillers’ dried grains with solubles | 40.00 | |

| Wheat bran | 50.00 | |

| Soybean hulls | 130.00 | |

| CaHPO4/Limestone | 5.00 | |

| Premix 1 | 40.00 | |

| Total | 1000.00 | |

| Nutritional components 2 | Dry matter | 889.20 |

| Crude protein | 142.50 | |

| Ether extract | 32.30 | |

| Ash | 75.10 | |

| Neutral detergent fiber | 385.20 | |

| Acid detergent fiber | 210.40 | |

| Calcium | 6.80 | |

| Phosphorus | 4.20 | |

| Metabolizable energy (MJ/kg) 3 | 10.22 |

| Parameter | Lower Group | Middle Group | High Group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC(109/L) | 8.65 ± 1.42 a,b | 17.48 ± 1.51 a | 23.28 ± 4.21 b | <0.001 |

| LYM% (%) | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 0.05 ± 0.05 | 0.083 |

| MCV (fL) | 26.27 ± 3.43 | 25.93 ± 2.65 | 24.50 ± 2.31 | 0.324 |

| MID% (%) | 2.93 ± 0.52 | 3.50 ± 1.58 | 2.26 ± 0.75 | 0.103 |

| HCT (%) | 39.49 ± 9.86 | 36.57 ± 4.76 | 38.08 ± 9.99 | 0.829 |

| RBC (1012/L) | 14.86 ± 2.01 | 14.10 ± 0.93 | 15.44 ± 3.06 | 0.212 |

| MCHC (g/L) | 378.06 ± 57.39 | 372.17 ± 18.56 | 411.50 ± 64.01 | 0.218 |

| GRAN% (%) | 96.89 ± 0.45 | 96.37 ± 1.28 | 97.69 ± 0.80 | 0.087 |

| GRAN# (109/L) | 8.44 ± 1.82 a,b | 16.90 ± 1.36 a | 22.09 ± 4.85 b | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zeng, M.; Zhou, H.; Wu, Q.; Wang, K.; Liu, H.; Yang, Y.; Peng, W.; Chen, A.; Deng, X.; Ji, C.; et al. Diversity Analysis of Fecal Microbiota in Goats Driven by White Blood Cell Count. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010259

Zeng M, Zhou H, Wu Q, Wang K, Liu H, Yang Y, Peng W, Chen A, Deng X, Ji C, et al. Diversity Analysis of Fecal Microbiota in Goats Driven by White Blood Cell Count. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):259. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010259

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Meng, Hanlin Zhou, Qun Wu, Ke Wang, Hu Liu, Yuanting Yang, Weishi Peng, Anmiao Chen, Xiaoyan Deng, Chihai Ji, and et al. 2026. "Diversity Analysis of Fecal Microbiota in Goats Driven by White Blood Cell Count" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010259

APA StyleZeng, M., Zhou, H., Wu, Q., Wang, K., Liu, H., Yang, Y., Peng, W., Chen, A., Deng, X., Ji, C., Zhang, X., & Han, J. (2026). Diversity Analysis of Fecal Microbiota in Goats Driven by White Blood Cell Count. Microorganisms, 14(1), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010259