Resolving the “Thick-Wall Challenge” in Haematococcus pluvialis: From Metabolic Reprogramming to Clinical Translation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Core Progress: Innovations in Production and Extraction Technologies

3. Process Innovation: Solvent-Free Extraction and Biorefinery Integration

4. Core Progress: Biological Activity and Delivery Systems

5. Existing Controversies and Limitations

6. Future Directions

| Future Direction | Key Technology/Strategy | Mechanism and Approach | Expected Outcome/Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

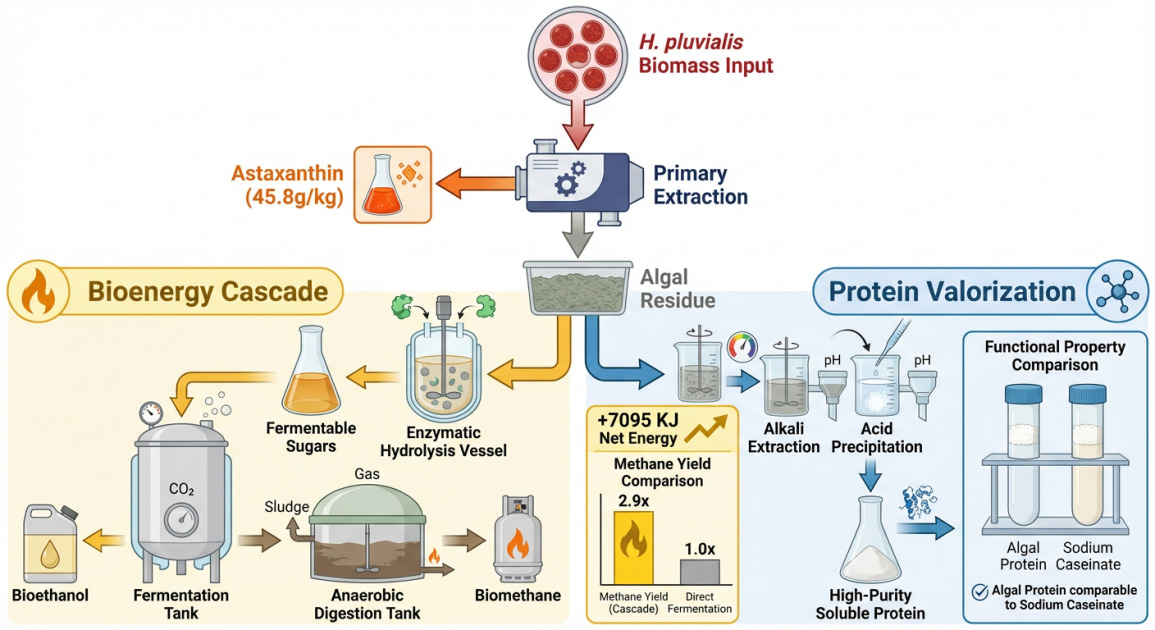

| Energy Co-production | Biofuel Generation | Anaerobic digestion and fermentation of algal waste streams. | Co-production of bioethanol and biomethane; offsets energy costs of cultivation. | [117] |

| Precision Biomanufacturing | Synthetic Biology (CRISPR/Cas9) | Genetic “redesign”: Downregulating cell wall genes while overexpressing synthesis genes (BKT/CHY). | Creation of “thin-walled, high-yield” strains; elimination of mechanical disruption steps. | [118] |

| Clinical Translation | Evidence-based Medicine | Large-scale, multi-center RCTs targeting aging-related diseases | Validation of therapeutic effects; establishment of standardized analytical methods and quality fingerprinting. | [119] |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma, P.; Nandave, M.; Nandave, D.; Yadav, S.; Vargas-De-La-Cruz, C.; Singh, S.; Tandon, R.; Ramniwas, S.; Behl, T. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated oxidative stress in chronic liver diseases and its mitigation by medicinal plants. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2023, 15, 6321–6341. [Google Scholar]

- Alateyah, N.; Ahmad, S.M.S.; Gupta, I.; Fouzat, A.; Thaher, M.I.; Das, P.; Al, M.A.E.; Ouhtit, A. Haematococcus pluvialis Microalgae Extract Inhibits Proliferation, Invasion, and Induces Apoptosis in Breast Cancer Cells. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 882956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mularczyk, M.; Michalak, I.; Marycz, K. Astaxanthin and other Nutrients from Haematococcus pluvialis-Multifunctional Applications. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurčacková, Z.; Ciglanová, D.; Mudroňová, D.; Tumová, L.; Bárcenas-Pérez, D.; Kopecký, J.; Koščová, J.; Cheel, J.; Hrčková, G. Astaxanthin Extract from Haematococcus pluvialis and Its Fractions of Astaxanthin Mono- and Diesters Obtained by CCC Show Differential Antioxidant and Cytoprotective Effects on Naïve-Mouse Spleen Cells. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A.; Jazini, M.; Mahdieh, M.; Karimi, K. Efficient superantioxidant and biofuel production from microalga Haematococcus pluvialis via a biorefinery approach. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 306, 123100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappalardo, I.; Santarsiero, A.; Radice, R.P.; Martelli, G.; Grassi, G.; de Oliveira, M.R.; Infantino, V.; Todisco, S. Effects of extracts of two selected strains of Haematococcus pluvialis on adipocyte function. Life 2023, 13, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurčacková, Z.; Ciglanová, D.; Mudroňová, D.; Bárcenas-Pérez, D.; Cheel, J.; Hrčková, G. Influence of standard culture conditions and effect of oleoresin from the microalga Haematococcus pluvialis on splenic cells from healthy Balb/c mice—A pilot study. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2023, 59, 764–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Xie, J.; Xia, Z.; Chen, X.; Xiao, J.; Cao, Y.; Liu, X. A novel peptide derived from Haematococcus pluvialis residue exhibits anti-aging activity in Caenorhabditis elegans via the insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 5576–5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deniz, I. Scaling-up of Haematococcus pluvialis production in stirred tank photobioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 310, 123434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambati, R.R.; Phang, S.M.; Ravi, S.; Aswathanarayana, R.G. Astaxanthin: Sources, extraction, stability, biological activities and its commercial applications–A review. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhu, X.; Yu, X.; Li, S.; Wang, K.; Wei, L.; Li, R.; Qin, S. Advancements of astaxanthin production in Haematococcus pluvialis: Update insight and way forward. Biotechnol. Adv. 2025, 79, 108519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarza, J.I.; Arredondo, V.B.O.; Villón, J.; Henríquez, V. Deesterification of astaxanthin and intermediate esters from Haematococcus pluvialis subjected to stress. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 23, e00351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, R.; Xue, W. Extraction of Astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis and Preparation of Astaxanthin Liposomes. Molecules 2024, 29, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Cao, Q.; Orfila, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Effects of Astaxanthin on Human Skin Ageing. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Kim, J.E.; Pak, K.J.; Kang, J.I.; Kim, T.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Yeo, I.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Kang, N.J.; et al. A Combination of Soybean and Haematococcus Extract Alleviates Ultraviolet B-Induced Photoaging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, N.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H. Astaxanthin Protects Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells from Oxidative Stress Induced by Blue Light Emitting Diodes. Food Sci. 2021, 42, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Wilawan, B.; Chan, S.S.; Ling, T.C.; Show, P.L.; Ng, E.P.; Jonglertjunya, W.; Phadungbut, P.; Khoo, K.S. Advancement of Carotenogenesis of Astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis: Recent Insight and Way Forward. Mol. Biotechnol. 2024, 66, 402–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, G.; Di Cerbo, A.; Giovazzino, A.; Rubino, V.; Palatucci, A.T.; Centenaro, S.; Fraccaroli, E.; Cortese, L.; Bonomo, M.G.; Ruggiero, G.; et al. In vitro effects of some botanicals with anti-inflammatory and antitoxic activity. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 2016, 5457010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Xu, J.; Yang, L.; Gu, C.; Xue, C. Thermal stability and oral absorbability of astaxanthin esters from Haematococcus pluvialis in Balb/c mice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 3662–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorović, B.; Grujić, V.J.; Krajnc, A.U.; Kranvogl, R.; Ambrožič-Dolinšek, J. Identification and Content of Astaxanthin and Its Esters from Microalgae Haematococcus pluvialis by HPLC-DAD and LC-QTOF-MS after Extraction with Various Solvents. Plants 2021, 10, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T.O.; McDougall, G.J.; Campbell, R.; Stanley, M.S.; Day, J.G. Media Screening for Obtaining Haematococcus pluvialis Red Motile Macrozooids Rich in Astaxanthin and Fatty Acids. Biology 2017, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherabli, A.; Grimi, N.; Lemaire, J.; Vorobiev, E.; Lebovka, N. Extraction of Valuable Biomolecules from the Microalga Haematococcus pluvialis Assisted by Electrotechnologies. Molecules 2023, 28, 2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, K.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Ooi, C.W.; Fu, X.; Miao, X.; Ling, T.C.; Show, P.L. Recent advances in biorefinery of astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 288, 121606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwotka-Suszczak, A.M.; Marcinkowska, K.A.; Smieszek, A.; Michalak, I.M.; Grzebyk, M.; Wiśniewski, M.; Marycz, K.M. The Haematococcus pluvialis extract enriched by bioaccumulation process with Mg(II) ions improves insulin resistance in equine adipose-derived stromal cells (EqASCs). Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 116, 108972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmann, I.K.; Möller, S.; Elle, C.; Hindersin, S.; Kramer, A.; Labes, A. Optimization of Astaxanthin Recovery in the Downstream Process of Haematococcus pluvialis. Foods 2022, 11, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Xu, N.; Liu, K.; Lv, R.; Shi, J.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Hu, C. Increasing production and bio-accessibility of natural astaxanthin in Haematococcus pluvialis by screening and culturing red motile cells under high light condition. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 364, 128067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Tan, X.H.; Liu, Z.W.; Aadil, R.M.; Tan, Y.C.; Inam-ur-Raheem, M. Mechanisms of Breakdown of Haematococcus pluvialis Cell Wall by Ionic Liquids, Hydrochloric Acid and Multi-enzyme Treatment. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 3182–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Luo, T.; Ye, N. A Review: Methods of Astaxanthin Extraction from Alga Haematococcus Pluvialis. Fish. Sci. 2020, 29, 745–748. [Google Scholar]

- Sanzo, G.D.; Mehariya, S.; Martino, M.; Larocca, V.; Casella, P.; Chianese, S.; Musmarra, D.; Balducchi, R.; Molino, A. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of astaxanthin, lutein, and fatty acids from Haematococcus pluvialis microalgae. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassani, J.C.; da Cunha, S.; de Assis Leite, D.C.; Endres, C.M.; Pelisser, C.; Meneghetti, K.L.; Bombo, G.; Morais, A.M.M.B.; Morais, R.M.S.C.; Backes, G.T.; et al. Exploring the Potential of Haematococcus pluvialis as a Source of Bioactives for Food Applications: A Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, E.J.; Heo, S.Y.; Park, A.; Lee, Y.J.; Choi, W.Y.; Heo, S.J. Serum-Free Medium Supplemented with Haematococcus pluvialis Extracts for the Growth of Human MRC-5 Fibroblasts. Foods 2024, 13, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, A.; Rimauro, J.; Casella, P.; Cerbone, A.; Larocca, V.; Chianese, S.; Karatza, D.; Mehariya, S.; Ferraro, A.; Hristoforou, E.; et al. Extraction of astaxanthin from microalga Haematococcus pluvialis in red phase by using generally recognized as safe solvents and accelerated extraction. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 283, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Guan, B.; Kong, Q.; Geng, Z.; Wang, N. Repeated cultivation: Non-cell disruption extraction of astaxanthin for Haematococcus pluvialis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Ahirwar, A.; Singh, S.; Lodhi, R.; Lodhi, A.; Rai, A.; Jadhav, D.A.; Harish; Varjani, S.; Singh, G.; et al. Astaxanthin as a King of Ketocarotenoids: Structure, Synthesis, Accumulation, bioaccessibility and Antioxidant Properties. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, T. Attached Cultivation of Haematococcus pluvialis for Astaxanthin Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 158, 329–335, Erratum in Bioresour Technol. 2015, 185, 456.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Hu, T.; Yao, S.; Hu, C.; Xing, H.; Liu, K.; Sun, X.; Xu, N. Enhancement of astaxanthin production, recovery, and bio-accessibility in Haematococcus pluvialis through taurine-mediated inhibition of secondary cell wall formation under high light conditions. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 389, 129802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Cui, D.; Sun, X.; Shi, J.; Xu, N. Primary Metabolism is Associated with the Astaxanthin Biosynthesis in the Green Algae Haematococcus pluvialis under Light Stress. Algal Res. Biomass Biofuels Bioprod. 2020, 46, 101768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Cheng, J.; Lu, H.; Yang, W.; Zhou, J.; Cen, K. Transcriptome-based Analysis on Carbon Metabolism of Haematococcus pluvialis Mutant under 15% CO2. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 233, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ba, F.; Ursu, A.V.; Laroche, C.; Djelveh, G. Haematococcus pluvialis soluble proteins: Extraction, characterization, concentration/fractionation and emulsifying properties. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 200, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zhang, L.; Yu, W.; Liu, J. A strategy for interfering with the formation of thick cell walls in Haematococcus pluvialis by down-regulating the mannan synthesis pathway. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 362, 127783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Wu, J.; Wu, X.; Yuan, Q.; Chan, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; Yan, S. Size-Tunable Elasto-Inertial Sorting of Haematococcus pluvialis in the Ultrastretchable Microchannel. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 13338–13345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Lao, Y.M.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, H.J.; Cai, Z.H. Optimization of extraction solvents, solid phase extraction and decoupling for quantitation of free isoprenoid diphosphates in Haematococcus pluvialis by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1598, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtin, K.; Kuehnle, M.; Rehbein, J.; Schuler, P.; Nicholson, G.; Albert, K. Determination of astaxanthin and astaxanthin esters in the microalgae Haematococcus pluvialis by LC-(APCI)MS and characterization of predominant carotenoid isomers by NMR spectroscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 395, 1613–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipaúba-Tavares, L.H.; Tedesque, M.G.; Colla, L.C.; Millan, R.N.; Scardoeli-Truzzi, B. Effect of untreated and pretreated sugarcane molasses on growth performance of Haematococcus pluvialis microalgae in inorganic fertilizer and macrophyte extract culture media. Braz. J. Biol. 2022, 82, e263282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhao, J. Enhancement of astaxanthin accumulation in Haematococcus pluvialis by exogenous oxaloacetate combined with nitrogen deficiency. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 345, 126484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.E.; Yu, B.S.; Sim, S.J. Enhanced astaxanthin production of Haematococcus pluvialis strains induced salt and high light resistance with gamma irradiation. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 372, 128651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.H.; Chun, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Park, C.; Yoo, H.Y.; Kwak, H.S. Improved Productivity of Astaxanthin from Photosensitive Haematococcus pluvialis Using Phototaxis Technology. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Leng, K.; Miao, J.; Su, D.; Zhao, L.; Yu, Y. Enhancing astaxanthin accumulation in immobilized Haematococcus pluvialis via alginate hydrogel membrane. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 292, 139145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, R.; Liu, K.; Chen, F.; Xing, H.; Xu, N.; Sun, X.; Hu, C. Buffering culture solution significantly improves astaxanthin production efficiency of mixotrophic Haematococcus pluvialis. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 354, 127175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Babazadeh, B.A.; Razeghi, J.; Jafarirad, S.; Motafakkerazad, R. Are biosynthesized nanomaterials toxic for the environment? Effects of perlite and CuO/perlite nanoparticles on unicellular algae Haematococcus pluvialis. Ecotoxicology 2021, 30, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, K.S.; Chew, K.W.; Ooi, C.W.; Ong, H.C.; Ling, T.C.; Show, P.L. Extraction of natural astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis using liquid biphasic flotation system. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 290, 121794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aye Myint, A.; Hariyanto, P.; Irshad, M.; Ruqian, C.; Wulandari, S.; Eui Hong, M.; Jun Sim, S.; Kim, J. Strategy for high-yield astaxanthin recovery directly from wet Haematococcus pluvialis without pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 346, 126616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, C.; Zhu, M.; Chen, F.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Gao, X. Astaxanthin, Haematococcus pluvialis and Haematococcus pluvialis Residue Alleviate Liver Injury in D-Galactose-induced Aging Mice through Gut-liver Axis. J. Oleo Sci. 2024, 73, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussagy, C.U.; Pereira, J.F.B.; Santos-Ebinuma, V.C.; Pessoa, A., Jr.; Raghavan, V. Insights into using green and unconventional technologies to recover natural astaxanthin from microbial biomass. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 11211–11225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satchasataporn, K.; Khunbutsri, D.; Chopjitt, P.; Sutjarit, S.; Pan-Utai, W.; Meekhanon, N. Antimicrobial resistance patterns of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in dogs from Thailand: Evaluation of algal extracts as novel antimicrobial agents. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.A.; Oh, Y.K.; Lee, J.; Sim, S.J.; Hong, M.E.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, J.S. High-efficiency cell disruption and astaxanthin recovery from Haematococcus pluvialis cyst cells using room-temperature imidazolium-based ionic liquid/water mixtures. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 274, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, M.F.; Morais, A.M.; Morais, R.M. Effects of spray-drying and storage on astaxanthin content of Haematococcus pluvialis biomass. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 1253–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Han, L.; Yuan, Y. Effect of Solvents on extract of astaxanthin from green algae Haematococcus pluvialis. Mar. Sci. 2012, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Y.; Chen, F.; Liu, X.J.; Wang, J.H.; Huang, X.S. Study on Extraction Conditions of Astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis. Food Sci. 2006, 27, 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Gao, J. Selectively extraction of astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis by aqueous biphasic systems composed of ionic liquids and deep eutectic solutions. Food Chem. 2024, 434, 137399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranga, R.; Sarada, A.R.; Baskaran, V.; Ravishankar, G.A. Identification of carotenoids from green alga Haematococcus pluvialis by HPLC and LC-MS (APCI) and their antioxidant properties. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 19, 1333–1341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.K.; Albarico, F.P.J.B.; Perumal, P.K.; Vadrale, A.P.; Nian, C.T.; Chau, H.T.B.; Anwar, C.; Wani, H.M.U.D.; Pal, A.; Saini, R.; et al. Algae as an emerging source of bioactive pigments. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 351, 126910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, L.J.; Seop, L.J.; Jun, S.S. Enhanced toxicity-free astaxanthin extraction from Haematococcus pluvialis via concurrent cell disruption and demulsification. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 406, 130974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez, M.I.; Suárez, M.D.; Alarcón, F.J.; Martínez, T.F. Assessing the potential of algae extracts for extending the shelf life of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fillets. Foods 2021, 10, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, T.A.; Kwan, S.E.; Peccia, J.; Zimmerman, J.B. Selectively biorefining astaxanthin and triacylglycerol co-products from microalgae with supercritical carbon dioxide extraction. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 269, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, F.R.; Trevisol, T.C.; Burkert, C.A.; Machado, F.R.; Boschetto, D.L.; Burkert, J.F.; Ferreira, S.R.; Oliveira, J.V. Technological process for cell disruption, extraction and encapsulation of astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 218, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemani, N.; Dehnavi, S.M.; Pazuki, G. Extraction and separation of astaxanthin with the help of pre-treatment of Haematococcus pluvialis microalgae biomass using aqueous two-phase systems based on deep eutectic solvents. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Oh, Y.K.; Choi, S.A.; Kim, M.C. Recovery of Astaxanthin-Containing Oil from Haematococcus pluvialis by Nano-dispersion and Oil Partitioning. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 190, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Youn, L.S.; Lakshmi, N.A.; Kim, S.; Oh, Y.K. Cell Disruption and Astaxanthin Extraction from Haematococcus pluvialis: Recent Advances. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 343, 126124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, N.B.; Ngo, D.N.; Tran, T.N.; Le, G.B.; Le, H.S.; Nguyen, M.H. Comparative evaluation of lipid-based nanocarriers encapsulating enriched astaxanthin extract from Haematococcus pluvialis: Preparation, characterization, and UVB protection. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Seo, J.M.; Nguyen, A.; Pham, T.X.; Park, H.J.; Park, Y.; Kim, B.; Bruno, R.S.; Lee, J. Astaxanthin-rich extract from the green alga Haematococcus pluvialis lowers plasma lipid concentrations and enhances antioxidant defense in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1611–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, E. Extensive Bioactivity of Astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis in Human. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1261, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.; Li, H.; Zhao, P.; Yu, R.; Pan, G.; Gao, S.; Xie, X.; Huang, A.; He, L.; Wang, G. Quantitative proteomic analysis of thylakoid from two microalgae (Haematococcus pluvialis and Dunaliella salina) reveals two different high light-responsive strategies. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (NDA); Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Cámara, M.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Jos, Á.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McNulty, B.; et al. Safety of the extension of use of oleoresin from Haematococcus pluvialis containing astaxanthin as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, M.; Egli, C.; Bartolome, R.A.; Sivamani, R.K. Ex vivo evaluation of a liposome-mediated antioxidant delivery system on markers of skin photoaging and skin penetration. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 17, 1481–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.N.; Ryu, S.J.; Sathiyaseelan, A.; Baek, J.S. Bioactive Molecules of Microalgae Haematococcus pluvialis-Mediated Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles: Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Antibiofilm, Hemolysis Assay, and Anticancer. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2025, 2025, 8876478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Too, H.P. Microbial astaxanthin biosynthesis: Recent achievements, challenges, and commercialization outlook. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 5725–5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.H.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, S.; Yoon, M.J.; Park, K.S. Chemical Transformation of Astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis Improves Its Antioxidative and Anti-inflammatory Activities. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 19120–19130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, A.; Tsuji, S.; Okada, Y.; Murakami, N.; Urami, M.; Nakagawa, K.; Ishikura, M.; Katagiri, M.; Koga, Y.; Shirasawa, T. Preliminary Clinical Evaluation of Toxicity and Efficacy of A New Astaxanthin-rich Haematococcus pluvialis Extract. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2009, 44, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, T.Y.; Sim, H.Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Ryu, S.; Baek, S.; Kim, D.G.; Sim, J.; An, H.J. Hot-Melt Extrusion Drug Delivery System-Formulated Haematococcus pluvialis Extracts Regulate Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Macrophages. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Lee, Y.J.; Jo, E.; Park, G.H.; Heo, S.Y.; Koh, E.J.; Lee, S.H.; Cha, S.H.; Heo, S.J. Serum-free media formulation using marine microalgae extracts and growth factor cocktails for Madin-Darby canine kidney and Vero cell cultures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Wu, Y.H.; Zhao, L.C.; Xiao, S.Y.; Zhou, A.M.; Liu, X. Determination of astaxanthin in Haematococcus pluvialis by first-order derivative spectrophotometry. J. AOAC Int. 2011, 94, 1752–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binatti, E.; Zoccatelli, G.; Zanoni, F.; Donà, G.; Mainente, F.; Chignola, R. Phagocytosis of astaxanthin-loaded microparticles modulates TGFβ production and intracellular ROS levels in J774A.1 macrophages. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Minceva, M. Techno-economic analysis of a new downstream process for the production of astaxanthin from the microalgae Haematococcus pluvialis. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chik, M.W.; Meor Mohd Affandi, M.M.R.; Mohd Nor Hazalin, N.A.; Surindar Singh, G.K. Astaxanthin nanoemulsion improves cognitive function and synaptic integrity in streptozotocin-induced Alzheimer’s disease model. Metab. Brain Dis. 2025, 40, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, Y.M.; Lin, Y.M.; Wang, X.S.; Xu, X.J.; Jin, H. An improved method for sensitive quantification of isoprenoid diphosphates in the astaxanthin-accumulating Haematococcus pluvialis. Food Chem. 2022, 375, 131911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Duan, C.; Yi, S.; Gao, Z.; Xiao, C.; Agathos, S.N.; Wang, G.; Li, J. Biotechnological production of astaxanthin from the microalga Haematococcus pluvialis. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 43, 107602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaró, S.; Ciardi, M.; Morillas-España, A.; Sánchez-Zurano, A.; Acién-Fernández, G.; Lafarga, T. Microalgae Derived Astaxanthin: Research and Consumer Trends and Industrial Use as Food. Foods 2021, 10, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viazau, Y.V.; Goncharik, R.G.; Kulikova, I.S.; Kulikov, E.A.; Vasilov, R.G.; Selishcheva, A.A. E/Z isomerization of astaxanthin and its monoesters in vitro under the exposure to light or heat and in overilluminated Haematococcus pluvialis cells. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinsipp, P.; Gerlza, T.; Kircher, J.; Zatloukal, K.; Jäger, C.; Pucher, P.; Kungl, A.J. Antiviral Activity of Haematococcus pluvialis Algae Extract Is Not Exclusively Due to Astaxanthin. Pathogens 2025, 14, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Z.; Dong, T.; Luo, Y.; Yan, W.; Wang, C.; Song, C. On-chip photoacoustics-activated cell sorting (PA-ACS) for label-free and high-throughput detection and screening of microalgal cells. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslanbay Guler, B.; Saglam-Metiner, P.; Deniz, I.; Demirel, Z.; Yesil-Celiktas, O.; Imamoglu, E. Aligned with sustainable development goals: Microwave extraction of astaxanthin from wet algae and selective cytotoxic effect of the extract on lung cancer cells. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 53, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.C.; Tam, L.T.; Hien, H.T.M.; Thu, N.T.H.; Hong, D.D.; Thom, L.T. Optimization of Culture Conditions for High Cell Productivity and Astaxanthin Accumulation in Vietnam’s Green Microalgae Haematococcus pluvialis HB and a Neuroprotective Activity of Its Astaxanthin. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehariya, S.; Sharma, N.; Iovine, A.; Casella, P.; Marino, T.; Larocca, V.; Molino, A.; Musmarra, D. An Integrated Strategy for Nutraceuticals from Haematoccus pluvialis: From Cultivation to Extraction. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, K.; Majzoub, M.E.; Taki, A.C.; Hernandez, S.M.; Magnusson, M.; Glasson, C.R.K.; de Nys, R.; Thomas, T.; Lopata, A.L.; Kamath, S.D. The Algal Polysaccharide Ulvan and Carotenoid Astaxanthin Both Positively Modulate Gut Microbiota in Mice. Foods 2022, 11, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yin, Z.; Ning, J.; Zhang, X.; Zou, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, H.; Fan, B.; Wang, F. Structural determinants of robust Pickering emulsions stabilized by microalgae-derived fibrous polysaccharide–protein complexes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 330, 148169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oninku, B.; Lomas, M.W.; Burr, G.; Aryee, A.N.A. Characterization of weakened Haematococcus pluvialis encapsulated in alginate-based hydrogel. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 5494–5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzajani, F.; Parniaei, N.; Mirzajani, F.; Ghaderi, A. Exploring the Bioactive Compounds of Haematococcus pluvialis for Resistant-Antimicrobial Applications in Diabetic Foot Ulcers Control. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2025, 24, e161297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasri, N.; Keyhanfar, M.; Behbahani, M.; Dini, G. Enhancement of astaxanthin production in Haematococcus pluvialis using zinc oxide nanoparticles. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 342, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, A.; Masson, L.; Velasco, J.; Del Valle, J.M.; Robert, P. Microencapsulation of H. pluvialis oleoresins with different fatty acid composition: Kinetic stability of astaxanthin and alpha-tocopherol. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Yu, G.; Zhou, W. Comparative metabolomic analysis of Haematococcus pluvialis during hyperaccumulation of astaxanthin under the high salinity and nitrogen deficiency conditions. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 41, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.M.; Gojkovic, Z.; Ferro, L.; Maza, M.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J.; Funk, C. Use of pulsed electric field permeabilization to extract astaxanthin from the Nordic microalga Haematococcus pluvialis. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.G.; Otero, P.; Echave, J.; Carreira-Casais, A.; Chamorro, F.; Collazo, N.; Jaboui, A.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M.A. Xanthophylls from the Sea: Algae as Source of Bioactive Carotenoids. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Bocanegra, A.R. Production, extraction, and quantification of astaxanthin by Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous or Haematococcus pluvialis: Standardized techniques. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 898, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Guan, F.; Wang, G.; Miao, L.; Ding, J.; Guan, G.; Li, Y.; Hui, B. Astaxanthin preparation by lipase-catalyzed hydrolysis of its esters from Haematococcus pluvialis algal extracts. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, C643–C650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medoro, A.; Davinelli, S.; Milella, L.; Willcox, B.J.; Allsopp, R.C.; Scapagnini, G.; Willcox, D.C. Dietary Astaxanthin: A Promising Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Agent for Brain Aging and Adult Neurogenesis. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, A.; Hooda, V.; Jain, U.; Chauhan, N. Astaxanthin: A nature’s versatile compound utilized for diverse applications and its therapeutic effects. 3 Biotech. 2025, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.; Pereira, J.M.; Marques-Oliveira, R.; Costa, I.; Gil-Martins, E.; Silva, R.; Remião, F.; Peixoto, A.F.; Sousa Lobo, J.M.; Silva, A.C. An in vitro evaluation of the potential neuroprotective effects of intranasal lipid nanoparticles containing astaxanthin obtained from different sources: Comparative studies. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.S.; Jang, Y.S.; Sathiyaseelan, A.; Ryu, S.J.; Lee, H.Y.; Baek, J.S. Antibiofilm and anticancer activity of multi-walled carbon nanotubes fabricated with hot-melt extruded astaxanthin-mediated synthesized silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanotta, D.; Puricelli, S.; Bonoldi, G. Cognitive effects of a dietary supplement made from extract of Bacopa monnieri, astaxanthin, phosphatidylserine, and vitamin E in subjects with mild cognitive impairment: A noncomparative, exploratory clinical study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, D.K.; Aydin, S. Production of new functional coconut milk kefir with blueberry extract and microalgae: The comparison of the prebiotic potentials on lactic acid bacteria of kefir grain and biochemical characteristics. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 61, 1986–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Tao, Q.; Xian, F.; Chen, Z.; Huang, L.; Zhong, N.; Gao, J. Development of pullulan/gellan gum films loaded with astaxanthin nanoemulsion for enhanced strawberry preservation. Food Res. Int. 2025, 201, 115644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, L.; Chen, X.; Han, J. Development and evaluation of astaxanthin as nanostructure lipid carriers in topical delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech 2020, 21, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Fei, Z.; Liu, G.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Lin, C.S.K.; Zhang, W.; Xin, F.; Jiang, M. The bioproduction of astaxanthin: A comprehensive review on the microbial synthesis and downstream extraction. Biotechnol. Adv. 2024, 74, 108392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambati, R.R.; Gogisetty, D.; Aswathanarayana, R.G.; Ravi, S.; Bikkina, P.N.; Bo, L.; Yuepeng, S. Industrial potential of carotenoid pigments from microalgae: Current trends and future prospects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 1880–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Wu, Z.; Wang, L.; Wan, S.; Qian, G.; Yan, H.; Deng, Y.; Shi, L. High-throughput sheathless focusing and sorting of flexible microalgae in spiral-coupled contraction-expansion channels. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2025, 11, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, S. Enhancement of Microbial Diversity and Methane Yield by Bacterial Bioaugmentation Through the Anaerobic Digestion of Haematococcus Pluvialis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 5631–5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basiony, M.; Ouyang, L.; Wang, D.; Yu, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, M.; Wang, X.; Feng, J.; Dai, J.; Shen, Y.; et al. Optimization of microbial cell factories for astaxanthin production: Biosynthesis and regulations, engineering strategies and fermentation optimization strategies. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2022, 7, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.; Pereira, S.; Otero, A.; Fiol, S.; Garcia-Jares, C.; Lores, M. Matrix solid-phase dispersion as a greener alternative to obtain bioactive extracts from Haematococcus pluvialis. Characterization by UHPLC-QToF. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 27995–28006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strategy | Method/Strain | Key Mechanism | Main Outcome/Efficiency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Regulation | exogenous oxaloacetate addition | exogenous OA promoted respiration over photosynthesis. | the metabolite levels in the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway, pentose phosphate pathway and tricarboxylic acid cycle obviously increased. | [45] |

| Strain Selection | H. pluvialis mutant M5 strain | Maintains motile cell morphology under stress; avoids thick-walled cyst formation. | M5 demonstrated an increase in biomass and astaxanthin productivity by 86.70% and 66.15%. | [46] |

| High-throughput Screening | A polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-based microfluidic device | using the negative phototaxis of the H. pluvialis to attain the mutants having high astaxanthin production. | 1.17-fold improved growth rate and 1.26-fold increases in astaxanthin production (55.12 ± 4.12 mg g−1) in the 100 L photo-bioreactor compared to the wild type. | [47] |

| Mixotrophy/Cost Reduction | novel fabrication method of alginate hydrogel membrane (AHM) | incorporates cotton gauze into a hydrogel with a low sodium alginate (SA) concentration of 0.5%, utilizing endogenous calcification. | A 70.8% increase in astaxanthin yield | [48] |

| Biofortification | Sodium acetate (NaAc) supplementation | Provides an exogenous acetate-derived carbon source that directly increases the intracellular acetyl-CoA pool, supporting both fatty acid synthesis (for lipid droplet formation) and astaxanthin esterification; efficacy is often dependent on nitrogen status and culture stage | Enhanced metabolic activity; improved | [49] |

| Method/Technology | Representative system and Conditions | Performance (as Reported) | Key Limitations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Cell Wall Disruption Technology; Polymer Microcapsule Encapsulation Technology | Enzymatic System; Encapsulation System | Technological Innovation: Pioneering the integration of enzymatic cell wall disruption, extraction, and supercritical encapsulation technologies for astaxanthin stabilization. Process Integrity: Achieving full-chain technological development from algal raw materials to functional products. | Process Complexity: Multi-step processes may increase production costs and operational complexity Scale-Up Challenges: Enzymatic digestion and supercritical encapsulation techniques developed at the laboratory scale may encounter technical barriers during industrial-scale expansion Cost-Effectiveness: The high cost of enzyme preparations and supercritical equipment may impact economic viability | [66] |

| DES-based aqueous two-phase system (ATPS) pretreatment + subsequent liquid–liquid extraction | 35% (w/w) deep eutectic solvent (choline chloride–urea), 30% (w/w) dipotassium hydrogen phosphate, 50 °C, pH = 7.5; followed by liquid–liquid extraction at 25 °C | >99% astaxanthin extracted under the above “mild conditions” | solvent reuse/recycling and product-grade compliance need validation at scale | [67] |

| Recovery of astaxanthin-containing oil by oil partitioning in an oil–acetone–water solution (after nano-dispersion) | Oil Partitioning (Vegetable Oil) | oil-recovery yield 97.8% in 10 g/L solution (partial acetone evaporation + soybean oil addition) | Produces edible astaxanthin-oil directly; reduces cost by ~3-fold (no drying/solvent recovery). | [68] |

| Mechanochemical Method; One-Pot Room-Temperature Extraction; | Mechanochemical method: Ball milling time 30–60 min, rotation speed 300–500 rpm, aqueous system One-pot method: Room temperature conditions, no additional heating required, processing time 2–4 h | Mechanical-chemical method: Extracts astaxanthin with high purity and no residual organic solvents. One-pot method: Extracts at room temperature with astaxanthin retention rates exceeding 95%. | Cost-effectiveness: New green extraction methods remain more expensive than traditional approaches. Process complexity: While innovative techniques like the one-pot method are highly efficient, they demand stringent process control. Lack of standardization: Different methods lack unified evaluation criteria and process parameters. | [69] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, T.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q. Resolving the “Thick-Wall Challenge” in Haematococcus pluvialis: From Metabolic Reprogramming to Clinical Translation. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010253

Chen T, Zhu X, Liao Q. Resolving the “Thick-Wall Challenge” in Haematococcus pluvialis: From Metabolic Reprogramming to Clinical Translation. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):253. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010253

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Tao, Xun Zhu, and Qiang Liao. 2026. "Resolving the “Thick-Wall Challenge” in Haematococcus pluvialis: From Metabolic Reprogramming to Clinical Translation" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010253

APA StyleChen, T., Zhu, X., & Liao, Q. (2026). Resolving the “Thick-Wall Challenge” in Haematococcus pluvialis: From Metabolic Reprogramming to Clinical Translation. Microorganisms, 14(1), 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010253