Antimicrobial Resistance and Comparative Genome Analysis of High-Risk Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Egyptian Children with Diarrhoea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Characterisation of E. coli Strains

2.2. Genome Sequencing

2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis of Genome Sequences

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Genome Characterisation of E. coli Strains

3.2. Analysis of Acquired AMR Genes and Chromosomal Point Mutations Associated with AMR

3.3. Characterisation of IncX3 Plasmids Carrying Carbapenem Resistance Determinants

3.4. Characterisation of IncF Plasmids Potentially Carrying Carbapenem Resistance Genes

3.5. Carriage of Virulence-Associated Genes in Egyptian E. coli Isolates

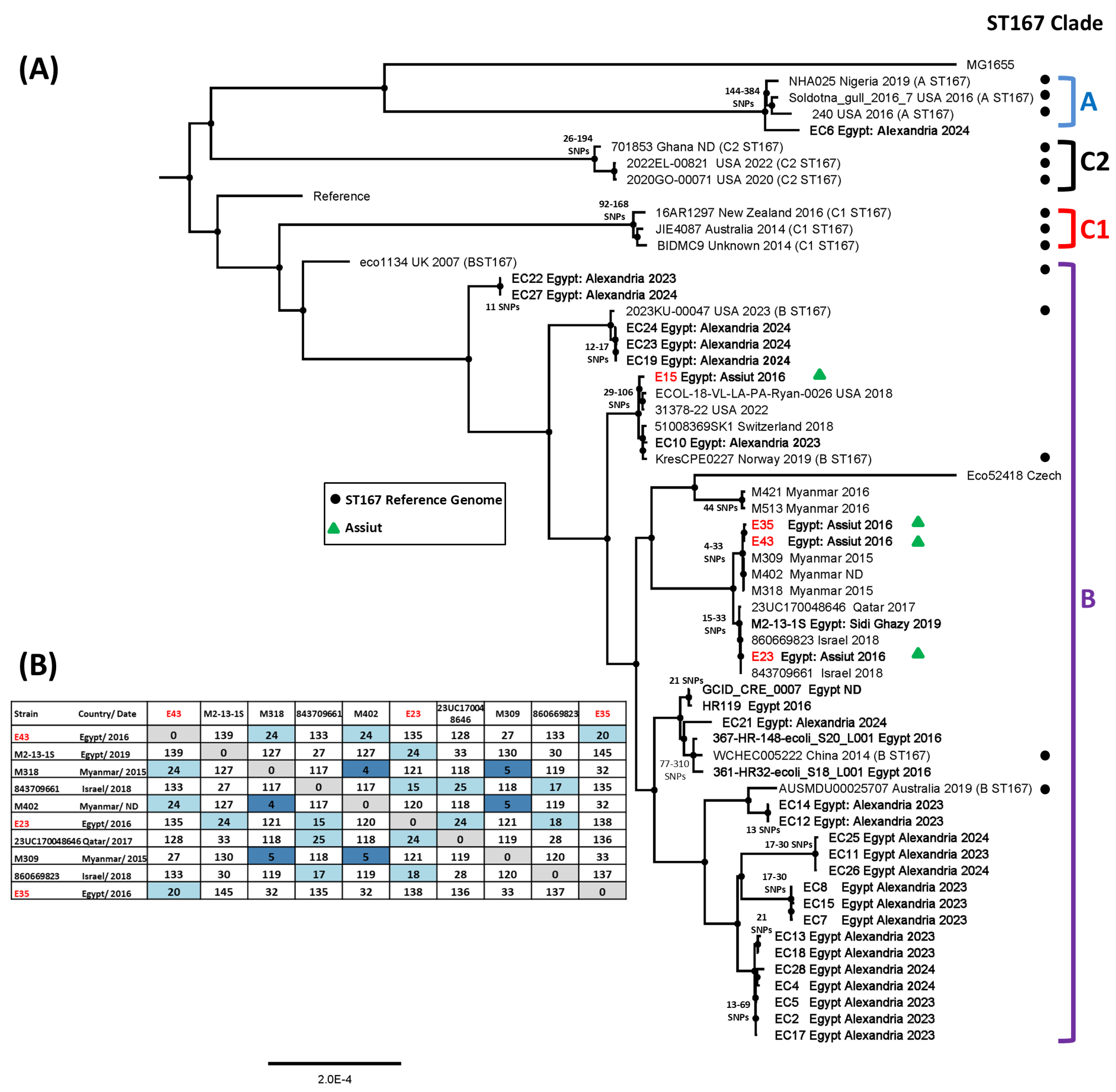

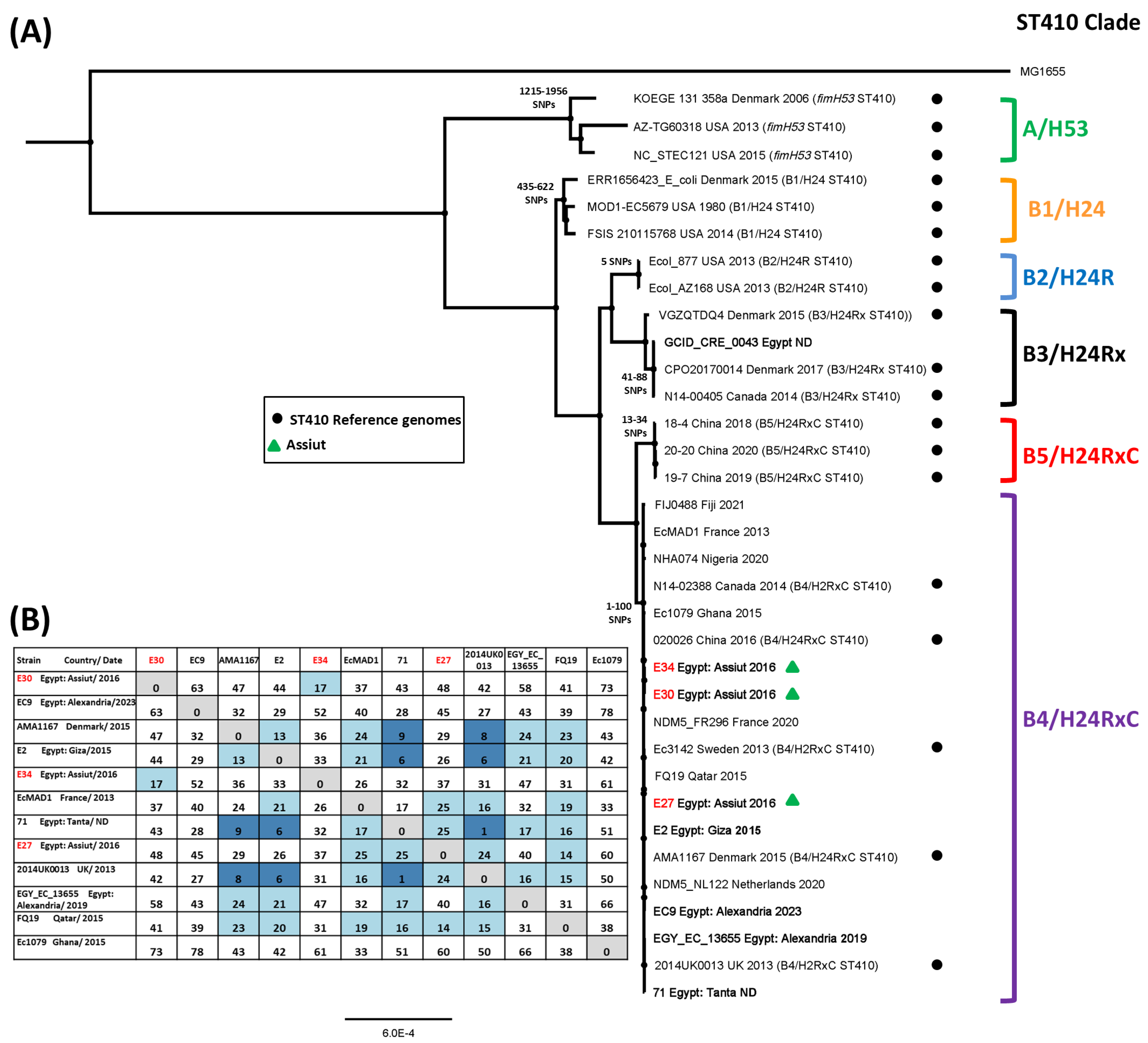

3.6. SNP Analysis of ST167 and ST410 Egyptian E. coli Isolates

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaper, J.B.; Nataro, J.P.; Mobley, H.L. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, L.W. Distinguishing Pathovars from Nonpathovars: Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2020, 8, AME0014-2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sati, H.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Hansen, P.; Garlasco, J.; Campagnaro, E.; Boccia, S.; Castillo-Polo, J.A.; Magrini, E.; Garcia-Vello, P.; et al. The WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024: A prioritisation study to guide research, development, and public health strategies against antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Feng, Y.; Tang, G.; Qiao, F.; McNally, A.; Zong, Z. NDM Metallo-β-Lactamases and Their Bacterial Producers in Health Care Settings. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00115-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopotsa, K.; Osei Sekyere, J.; Mbelle, N.M. Plasmid evolution in carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: A review. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2019, 1457, 61–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tängdén, T.; Giske, C.G. Global dissemination of extensively drug-resistant carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: Clinical perspectives on detection, treatment and infection control. J. Intern. Med. 2015, 277, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhudhairy, M.K.; Saki, M.; Seyed–Mohammadi, S.; Jomehzadeh, N.; Khoshnood, S.; Moradzadeh, M.; Yazdansetad, S. Integron frequency of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urinary tract infection in Southwest of Iran. J. Acute Dis. 2019, 8, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlowsky, J.A.; Lob, S.H.; Kazmierczak, K.M.; Badal, R.E.; Young, K.; Motyl, M.R.; Sahm, D.F. In Vitro Activity of Imipenem against Carbapenemase-Positive Enterobacteriaceae Isolates Collected by the SMART Global Surveillance Program from 2008 to 2014. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirano, G.; Chen, L.; Nobrega, D.; Finn, T.J.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; DeVinney, R.; Pitout, J.D.D. Genomic Epidemiology of Global Carbapenemase-Producing Escherichia coli, 2015–2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamal, D.; Fernández-Martínez, M.; El-Defrawy, I.; Ocampo-Sosa, A.A.; Martínez-Martínez, L. First identification of NDM-5 associated with OXA-181 in Escherichia coli from Egypt. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2016, 5, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.M.; Ramadan, H.; Sadek, M.; Nariya, H.; Shimamoto, T.; Hiott, L.M.; Frye, J.G.; Jackson, C.R.; Shimamoto, T. Draft genome sequence of a bla(NDM-1)- and bla(OXA-244)-carrying multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli D-ST69 clinical isolate from Egypt. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 832–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.M.; Zakaria, A.S.; Edward, E.A. Genomic Characterization of International High-Risk Clone ST410 Escherichia coli Co-Harboring ESBL-Encoding Genes and bla(NDM-5) on IncFIA/IncFIB/IncFII/IncQ1 Multireplicon Plasmid and Carrying a Chromosome-Borne bla(CMY-2) from Egypt. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.D.; Rezk, S.; Brandt, C.; Reinicke, M.; Diezel, C.; Müller, E.; Frankenfeld, K.; Krähmer, D.; Monecke, S.; Ehricht, R. Tracking Multidrug Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria in Alexandria, Egypt (2020-2023): An Integrated Analysis of Patient Data and Diagnostic Tools. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakaria, A.S.; Edward, E.A.; Mohamed, N.M. Pathogenicity Islands in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Clinical Isolate of the Globally Disseminated O25:H4-ST131 Pandemic Clonal Lineage: First Report from Egypt. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, A.M.; Ramadan, H.; Shimamoto, T.; Komatsu, T.; Maruyama, F.; Shimamoto, T. Detection and Genomic Characteristics of NDM-19- and QnrS11-Producing O101:H5 Escherichia coli Strain Phylogroup A: ST167 from a Poultry Farm in Egypt. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, R.; Yasir, M.; Godfrey, R.E.; Christie, G.S.; Element, S.J.; Saville, F.; Hassan, E.A.; Ahmed, E.H.; Abu-Faddan, N.H.; Daef, E.A.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance and gene regulation in Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli from Egyptian children with diarrhoea: Similarities and differences. Virulence 2021, 12, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.V.; Cosentino, S.; Rasmussen, S.; Friis, C.; Hasman, H.; Marvig, R.L.; Jelsbak, L.; Sicheritz-Ponten, T.; Ussery, D.W.; Aarestrup, F.M.; et al. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joensen, K.G.; Tetzschner, A.M.; Iguchi, A.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Scheutz, F. Rapid and Easy In Silico Serotyping of Escherichia coli Isolates by Use of Whole-Genome Sequencing Data. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 2410–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattoli, A.; Zankari, E.; Garcia-Fernandez, A.; Voldby Larsen, M.; Lund, O.; Villa, L.; Moller Aarestrup, F.; Hasman, H. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joensen, K.G.; Scheutz, F.; Lund, O.; Hasman, H.; Kaas, R.S.; Nielsen, E.M.; Aarestrup, F.M. Real-time whole-genome sequencing for routine typing, surveillance, and outbreak detection of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 1501–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malberg Tetzschner, A.M.; Johnson, J.R.; Johnston, B.D.; Lund, O.; Scheutz, F. In Silico Genotyping of Escherichia coli Isolates for Extraintestinal Virulence Genes by Use of Whole-Genome Sequencing Data. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e01269-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, S.; Voldby Larsen, M.; Møller Aarestrup, F.; Lund, O. PathogenFinder--distinguishing friend from foe using bacterial whole genome sequence data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77302, Erratum in PLoS ONE. 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer Florensa, A.; Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Kaas, R.S.; Conradsen Clausen, P.T.L.; Nielsen, H.; Rost, B.; Aarestrup, F.M. Whole-genome prediction of bacterial pathogenic capacity on novel bacteria using protein language models, with PathogenFinder2. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolaia, V.; Kaas, R.S.; Ruppe, E.; Roberts, M.C.; Schwarz, S.; Cattoir, V.; Philippon, A.; Allesoe, R.L.; Rebelo, A.R.; Florensa, A.F.; et al. ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3491–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, N.R.; Abram, F.; Brennan, F.; Holmes, A.; Pritchard, L. Easy phylotyping of Escherichia coli via the EzClermont web app and command-line tool. Access Microbiol. 2020, 2, acmi000143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siguier, P.; Perochon, J.; Lestrade, L.; Mahillon, J.; Chandler, M. ISfinder: The reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, D32–D36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, D.; Grant, J.R.; Marcu, A.; Sajed, T.; Pon, A.; Liang, Y.; Wishart, D.S. PHASTER: A better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W16–W21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutherford, K.; Parkhill, J.; Crook, J.; Horsnell, T.; Rice, P.; Rajandream, M.A.; Barrell, B. Artemis: Sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 944–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J.R.; Enns, E.; Marinier, E.; Mandal, A.; Herman, E.K.; Chen, C.Y.; Graham, M.; Van Domselaar, G.; Stothard, P. Proksee: In-depth characterization and visualization of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W484–W492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, T.J.; Rutherford, K.M.; Berriman, M.; Rajandream, M.A.; Barrell, B.G.; Parkhill, J. ACT: The Artemis Comparison Tool. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3422–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmohsenin, B.; Wiese, A.; Ziemert, N. AutoMLST2: A web server for phylogeny and microbial taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, W45–W50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, N.P.; Päuker, B.; Baxter, L.; Gupta, A.; Bunk, B.; Overmann, J.; Diricks, M.; Dreyer, V.; Niemann, S.; Holt, K.E.; et al. EnteroBase in 2025: Exploring the genomic epidemiology of bacterial pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D757–D762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The NCBI Pathogen Detection Project; National Center for Biotechnology Information: Bethesda, MD, USA; National Library of Medicine: Bethesda, MD, USA; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Saratto, T.; Visuri, K.; Lehtinen, J.; Ortega-Sanz, I.; Steenwyk, J.L.; Sihvonen, S. Solu: A cloud platform for real-time genomic pathogen surveillance. BMC Bioinform. 2025, 26, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534, Erratum in Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.L.; Phan, M.D.; Permana, B.; Lian, Z.J.; Nhu, N.T.K.; Cuddihy, T.; Peters, K.M.; Ramsay, K.A.; Stewart, C.; Pfennigwerth, N.; et al. Emergence of a carbapenem-resistant atypical uropathogenic Escherichia coli clone as an increasing cause of urinary tract infection. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roer, L.; Overballe-Petersen, S.; Hansen, F.; Schønning, K.; Wang, M.; Røder, B.L.; Hansen, D.S.; Justesen, U.S.; Andersen, L.P.; Fulgsang-Damgaard, D.; et al. Escherichia coli Sequence Type 410 Is Causing New International High-Risk Clones. mSphere 2018, 3, e00337-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, X.; Guo, Y.; Moran, R.A.; Doughty, E.L.; Liu, B.; Yao, L.; Li, J.; He, N.; Shen, S.; Li, Y.; et al. Global emergence of a hypervirulent carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli ST410 clone. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Fernandez, A.; Villa, L.; Bibbolino, G.; Bressan, A.; Trancassini, M.; Pietropaolo, V.; Venditti, M.; Antonelli, G.; Carattoli, A. Novel Insights and Features of the NDM-5-Producing Escherichia coli Sequence Type 167 High-Risk Clone. mSphere 2020, 5, e00269-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Lv, C.; Li, M.; Rahman, T.; Chang, Y.F.; Guo, X.; Song, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Q.; Ni, P.; et al. Carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli exhibit diverse spatiotemporal epidemiological characteristics across the globe. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manges, A.R.; Geum, H.M.; Guo, A.; Edens, T.J.; Fibke, C.D.; Pitout, J.D.D. Global Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) Lineages. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00135-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zankari, E.; Hasman, H.; Cosentino, S.; Vestergaard, M.; Rasmussen, S.; Lund, O.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Larsen, M.V. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2640–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machuca, J.; Ortiz, M.; Recacha, E.; Díaz-De-Alba, P.; Docobo-Perez, F.; Rodríguez-Martínez, J.M.; Pascual, Á. Impact of AAC(6′)-Ib-cr in combination with chromosomal-mediated mechanisms on clinical quinolone resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 3066–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, J.; Nassour, E.; Jisr, T.; El Chaar, M.; Tokajian, S. Characterization of bla(NDM-19)-producing IncX3 plasmid isolated from carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patiño-Navarrete, R.; Rosinski-Chupin, I.; Cabanel, N.; Gauthier, L.; Takissian, J.; Madec, J.Y.; Hamze, M.; Bonnin, R.A.; Naas, T.; Glaser, P. Stepwise evolution and convergent recombination underlie the global dissemination of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahazu, S.; Prah, I.; Ayibieke, A.; Sato, W.; Hayashi, T.; Suzuki, T.; Iwanaga, S.; Ablordey, A.; Saito, R. Possible Dissemination of Escherichia coli Sequence Type 410 Closely Related to B4/H24RxC in Ghana. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 770130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudejova, K.; Kraftova, L.; Mattioni Marchetti, V.; Hrabak, J.; Papagiannitsis, C.C.; Bitar, I. Genetic Plurality of OXA/NDM-Encoding Features Characterized From Enterobacterales Recovered From Czech Hospitals. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 641415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, Y.; Akeda, Y.; Hagiya, H.; Sakamoto, N.; Takeuchi, D.; Shanmugakani, R.K.; Motooka, D.; Nishi, I.; Zin, K.N.; Aye, M.M.; et al. Spreading Patterns of NDM-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Clinical and Environmental Settings in Yangon, Myanmar. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01924-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomehzadeh, N.; Ahmadi, K.; Javaherizadeh, H.; Afzali, M. The first evaluation relationship of integron genes and the multidrug-resistance in class A ESBLs genes in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains isolated from children with diarrhea in Southwestern Iran. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomezadeh, N.; Farajzadeh Sheikh, A.; Khosravi, A.D.; Amin, M. Detection of Shiga Toxin Producing E. coli Strains Isolated from Stool Samples of Patients with Diarrhea in Abadan Hospitals, Iran. J. Biol. Sci. 2009, 9, 820–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, P.; Tramonti, A.; De Biase, D. Coping with low pH: Molecular strategies in neutralophilic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 1091–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.J.; Wannemuehler, Y.M.; Nolan, L.K. Evolution of the iss gene in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 2360–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, I.F.N.; Boisen, N.; Silva, J.D.Q.; Havt, A.; de Carvalho, E.B.; Soares, A.M.; Lima, N.L.; Mota, R.M.S.; Nataro, J.P.; Guerrant, R.L.; et al. Prevalence of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli and its virulence-related genes in a case-control study among children from north-eastern Brazil. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013, 62, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageorges, V.; Monteiro, R.; Leroy, S.; Burgess, C.M.; Pizza, M.; Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Desvaux, M. Molecular determinants of surface colonisation in diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli (DEC): From bacterial adhesion to biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 44, 314–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramoonjago, P.; Kaneko, M.; Kinoshita, T.; Ohtsubo, E.; Takeda, J.; Hong, K.S.; Inagi, R.; Inoue, K. Role of TraT protein, an anticomplementary protein produced in Escherichia coli by R100 factor, in serum resistance. J. Immunol. 1992, 148, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garénaux, A.; Caza, M.; Dozois, C.M. The Ins and Outs of siderophore mediated iron uptake by extra-intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 153, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisen, N.; Østerlund, M.T.; Joensen, K.G.; Santiago, A.E.; Mandomando, I.; Cravioto, A.; Chattaway, M.A.; Gonyar, L.A.; Overballe-Petersen, S.; Stine, O.C.; et al. Redefining enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC): Genomic characterization of epidemiological EAEC strains. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjøt-Rasmussen, L.; Ejrnæs, K.; Lundgren, B.; Hammerum, A.M.; Frimodt-Møller, N. Virulence factors and phylogenetic grouping of Escherichia coli isolates from patients with bacteraemia of urinary tract origin relate to sex and hospital- vs. community-acquired origin. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 302, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Siek, K.E.; Giddings, C.W.; Doetkott, C.; Johnson, T.J.; Fakhr, M.K.; Nolan, L.K. Comparison of Escherichia coli isolates implicated in human urinary tract infection and avian colibacillosis. Microbiology 2005, 151, 2097–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrie, C.L.; Da Silva, A.G.; Ingle, D.J.; Higgs, C.; Seemann, T.; Stinear, T.P.; Williamson, D.A.; Kwong, J.C.; Grayson, M.L.; Sherry, N.L.; et al. Key parameters for genomics-based real-time detection and tracking of multidrug-resistant bacteria: A systematic analysis. Lancet Microbe. 2021, 2, e575–e583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manges, A.R.; Johnson, J.R. Reservoirs of Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, UTI-0006-2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Tsukamoto, T.; Terai, A.; Kurazono, H.; Takeda, Y.; Yoshida, O. Genetic evidence supporting the fecal-perineal-urethral hypothesis in cystitis caused by Escherichia coli. J. Urol. 1997, 157, 1127–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, R.D.S.; Tacão, M.; Figueiredo, A.S.; Duarte, A.S.; Esposito, F.; Lincopan, N.; Manaia, C.M.; Henriques, I. Genotypic and phenotypic traits of bla(CTX-M)-carrying Escherichia coli strains from an UV-C-treated wastewater effluent. Water Res. 2020, 184, 116079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña-Lizárraga, J.A.; Gómez-Gil, B.; Rendón-Maldonado, J.G.; Delgado-Vargas, F.; Vega-López, I.F.; Báez-Flores, M.E. Genomic Profiling of Antibiotic-Resistant Escherichia coli Isolates from Surface Water of Agricultural Drainage in North-Western Mexico: Detection of the International High-Risk Lineages ST410 and ST617. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giufré, M.; Accogli, M.; Graziani, C.; Busani, L.; Cerquetti, M. Whole-Genome Sequences of Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli Strains Sharing the Same Sequence Type (ST410) and Isolated from Human and Avian Sources in Italy. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e00757-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayer, S.S.; Lim, S.; Hong, S.; Elnekave, E.; Johnson, T.; Rovira, A.; Vannucci, F.; Clayton, J.B.; Perez, A.; Alvarez, J. Genetic Determinants of Resistance to Extended-Spectrum Cephalosporin and Fluoroquinolone in Escherichia coli Isolated from Diseased Pigs in the United States. mSphere 2020, 5, e00990-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; An, J.U.; Guk, J.H.; Song, H.; Yi, S.; Kim, W.H.; Cho, S. Prevalence, Characteristics and Clonal Distribution of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase- and AmpC β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli Following the Swine Production Stages, and Potential Risks to Humans. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 710747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, B.J.; Kim, S.W.; Salaheen, S.; Hovingh, E.; Van Kessel, J.A.S. Virulome and genome analyses identify associations between antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors in highly drug-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from veal calves. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nittayasut, N.; Yindee, J.; Boonkham, P.; Yata, T.; Suanpairintr, N.; Chanchaithong, P. Multiple and High-Risk Clones of Extended-Spectrum Cephalosporin-Resistant and bla(NDM-5)-Harbouring Uropathogenic Escherichia coli from Cats and Dogs in Thailand. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Khurshid, M.; Arshad, M.I.; Muzammil, S.; Rasool, M.; Yasmeen, N.; Shah, T.; Chaudhry, T.H.; Rasool, M.H.; Shahid, A.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance: One Health One World Outlook. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 771510, Erratum in Front. Cell. Infect. 2024, 14, 1488430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, H.; Yang, J.; He, F. Genomic insights into a bla(NDM-5)-carrying Escherichia coli ST167 isolate recovered from faecal sample of a healthy individual in China. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 36, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, N.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, B.; Wang, G.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, Y. Characterization of an NDM-19-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strain harboring 2 resistance plasmids from China. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 93, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, S.; Keller, P.M.; Greiner, M.; Bruderer, V.; Imkamp, F. Detection of NDM-19, a novel variant of the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase with increased carbapenemase activity under zinc-limited conditions, in Switzerland. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 95, 114851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overballe-Petersen, S.; Roer, L.; Ng, K.; Hansen, F.; Justesen, U.S.; Andersen, L.P.; Stegger, M.; Hammerum, A.M.; Hasman, H. Complete Nucleotide Sequence of an Escherichia coli Sequence Type 410 Strain Carrying bla(NDM-5) on an IncF Multidrug Resistance Plasmid and bla(OXA-181) on an IncX3 Plasmid. Genome Announc. 2018, 6, e01542-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Nam, S.K.; Chang, H.E.; Park, K.U. Comparative Analysis of Short- and Long-Read Sequencing of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci for Application to Molecular Epidemiology. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 857801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, D.A.; Konganti, K.; Gill, J.J.; Davis, B.W.; Hillhouse, A.E.; Michalik, J.; Cross, H.R.; Smith, G.C.; Taylor, T.M.; Riggs, P.K. Complete Whole Genome Sequences of Escherichia coli Surrogate Strains and Comparison of Sequence Methods with Application to the Food Industry. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, H.A.; Abdelwahab, R.; Browning, D.F.; Aly, S.A. Genome Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae Strains, Carrying Hybrid Resistance-Virulence IncHI1B/FIB Plasmids, Isolated from an Egyptian Pediatric ICU. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizri, A.R.; El-Fattah, A.A.; Bazaraa, H.M.; Al Ramahi, J.W.; Matar, M.; Ali, R.A.N.; El Masry, R.; Moussa, J.; Abbas, A.J.A.; Aziz, M.A. Antimicrobial resistance landscape and COVID-19 impact in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon: A survey-based study and expert opinion. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kholy, A.; El-Mahallawy, H.A.; Elsharnouby, N.; Abdel Aziz, M.; Helmy, A.M.; Kotb, R. Landscape of Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections in Egypt: Survey and Literature Review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 1905–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egyptian_Drug_Authority. National Guidance for the Rational Use of Duplicate Antimicrobial Therapy. Available online: https://www.edaegypt.gov.eg/media/yvsalsgc/national-guidance-for-the-rational-use-of-duplicate.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Egyptian_Drug_Authority. National Guidelines for Preauthorization of Restricted Antimicrobials in Hospitals National Antimicrobial Rational Use Committee. Available online: https://www.edaegypt.gov.eg/media/0suhvkon/edrex-gl-cap-care-012-national-guidelines-for-preauthorization-of-restricted-antimicrobials-in-hospitals-2022-1-_.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Scicluna, E.A.; Borg, M.A.; Gür, D.; Rasslan, O.; Taher, I.; Redjeb, S.B.; Elnassar, Z.; Bagatzouni, D.P.; Daoud, Z. Self-medication with antibiotics in the ambulatory care setting within the Euro-Mediterranean region; results from the ARMed project. J. Infect. Public Health 2009, 2, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, H.; Rakab, M.S.; Elshehaby, A.; Gebreel, A.I.; Hany, M.; BaniAmer, M.; Sajed, M.; Yunis, S.; Mahmoud, S.; Hamed, M.; et al. Pharmacies and use of antibiotics: A cross sectional study in 19 Arab countries. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2024, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhadry, S.W.; Tahoon, M.A.H. Health literacy and its association with antibiotic use and knowledge of antibiotic among Egyptian population: Cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooling, K.L.; Kandeel, A.; Hicks, L.A.; El-Shoubary, W.; Fawzi, K.; Kandeel, Y.; Etman, A.; Lohiniva, A.L.; Talaat, M. Understanding Antibiotic Use in Minya District, Egypt: Physician and Pharmacist Prescribing and the Factors Influencing Their Practices. Antibiotics 2014, 3, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussally, K.; Abu-Sittah, G.; Gomez, F.G.; Fayad, A.A.; Farra, A. Antimicrobial resistance in the ongoing Gaza war: A silent threat. Lancet 2023, 402, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Tanous, O.; Mills, D.; Wispelwey, B.; Asi, Y.; Hammoudeh, W.; Dewachi, O. Antimicrobial resistance in a protracted war setting: A review of the literature from Palestine. mSystems 2025, 10, e0167924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aila, N.A.; El Aish, K.I.A. Six-year antimicrobial resistance patterns of Escherichia coli isolates from different hospitals in Gaza, Palestine. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI Document M100-S24; Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Twenty-Fourth Informational Supplement. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI): Wayne, PA, USA, 2014; Volume 34.

- Feng, Y.; Liu, L.; Lin, J.; Ma, K.; Long, H.; Wei, L.; Xie, Y.; McNally, A.; Zong, Z. Key evolutionary events in the emergence of a globally disseminated, carbapenem resistant clone in the Escherichia coli ST410 lineage. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souvorov, A.; Agarwala, R.; Lipman, D.J. SKESA: Strategic k-mer extension for scrupulous assemblies. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkey, J.; Loftus, M.J.; Prasad, A.; Vakatawa, T.; Prasad, V.; Tudravu, L.; Pragastis, K.; Wisniewski, J.; Harshegyi-Hand, T.; Blakeway, L.; et al. Genomic diversity of clinically relevant bacterial pathogens from an acute care hospital in Suva, Fiji. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 7, dlaf058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strain | Genome Size | Number of Contigs | Genes (CDS) | Sequence Type a | Serotype b | Phylotype c | AMR Profile d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E4 | 4,823,577 bp | 107 | 4618 | ST46 | O8:H4 | A | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 *, 6, 7 |

| E15 | 5,004,224 bp | 123 | 4669 | ST167 | O101:H9 | A | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

| E23 | 4,937,645 bp | 137 | 4621 | ST167 | O101:H5 | A | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

| E27 | 5,007,556 bp | 109 | 4719 | ST410 | O8:H9 | C | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

| E28 | 5,025,348 bp | 209 | 4697 | ST617 | O101:H10 | A | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

| E29 | 4,959,121 bp | 109 | 4676 | ST361 | O9:H30 | A | 1 *, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

| E30 | 4,842,681 bp | 105 | 4531 | ST410 | O8:H9 | C | 1 *, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

| E34 | 4,954,276 bp | 70 | 4648 | ST410 | O8:H9 | C | 1 *, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

| E35 | 5,039,562 bp | 178 | 4717 | ST167 | O101:H5 | A | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

| E43 | 4,921,700 bp | 154 | 4588 | ST167 | O101:H5 | A | 1 *, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

| Detected Plasmid Replicons a | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | IncFIA | IncFIB | IncFII | IncI | IncQ1 | IncY | IncX3 | p0111 | Col440II | Col(BS512) | ColKP3 | Col(MG828) | Number of Replicons |

| E4 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| E15 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| E23 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| E27 | 7 | ||||||||||||

| E28 b | 6 | ||||||||||||

| E29 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| E30 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| E34 | 5 | ||||||||||||

| E35 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| E43 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| Detected AMR Resistance Genes a | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaCTX-M-15 | blaCMY-2 | blaCMY-42 | blaNDM-1 | blaNDM-5 | blaNDM-19 | blaOXA-1 | blaOXA-9 | blaOXA-181 | blaOXA-244 | blaTEM-1B | qnrS1 | aac(3)-IId | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | aadA1 | aadA2 | aadA5 | aph(3′)-Ia | aph(3″)-Ib | aph(6)-Id | rmtB | mph(A) | sul1 | sul2 | dfrA1 | dfrA12 | dfrA14 | dfrA17 | tet(A) | tet(B) | catB3 | Total ARG | |

| E4 | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E15 | 12 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E23 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E27 | 10 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E28 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E29 | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E30 | 12 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E34 | 14 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E35 | 11 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E43 | 12 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abdelwahab, R.; Alhammadi, M.M.; Yasir, M.; Hassan, E.A.; Ahmed, E.H.; Abu-Faddan, N.H.; Daef, E.A.; Busby, S.J.W.; Browning, D.F. Antimicrobial Resistance and Comparative Genome Analysis of High-Risk Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Egyptian Children with Diarrhoea. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010247

Abdelwahab R, Alhammadi MM, Yasir M, Hassan EA, Ahmed EH, Abu-Faddan NH, Daef EA, Busby SJW, Browning DF. Antimicrobial Resistance and Comparative Genome Analysis of High-Risk Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Egyptian Children with Diarrhoea. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):247. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010247

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdelwahab, Radwa, Munirah M. Alhammadi, Muhammad Yasir, Ehsan A. Hassan, Entsar H. Ahmed, Nagla H. Abu-Faddan, Enas A. Daef, Stephen J. W. Busby, and Douglas F. Browning. 2026. "Antimicrobial Resistance and Comparative Genome Analysis of High-Risk Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Egyptian Children with Diarrhoea" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010247

APA StyleAbdelwahab, R., Alhammadi, M. M., Yasir, M., Hassan, E. A., Ahmed, E. H., Abu-Faddan, N. H., Daef, E. A., Busby, S. J. W., & Browning, D. F. (2026). Antimicrobial Resistance and Comparative Genome Analysis of High-Risk Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Egyptian Children with Diarrhoea. Microorganisms, 14(1), 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010247