Forest Type Shapes Soil Microbial Carbon Metabolism: A Metagenomic Study of Subtropical Forests on Lushan Mountain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description and Sample Collection

2.2. Soil DNA Extraction, Metagenomics Sequencing, and Bioinformatic Analysis

2.3. Determination of Soil Physicochemical Properties

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Soil Physicochemical Properties

3.2. Microbial Community

3.3. C- Fixation Pathways and Genes

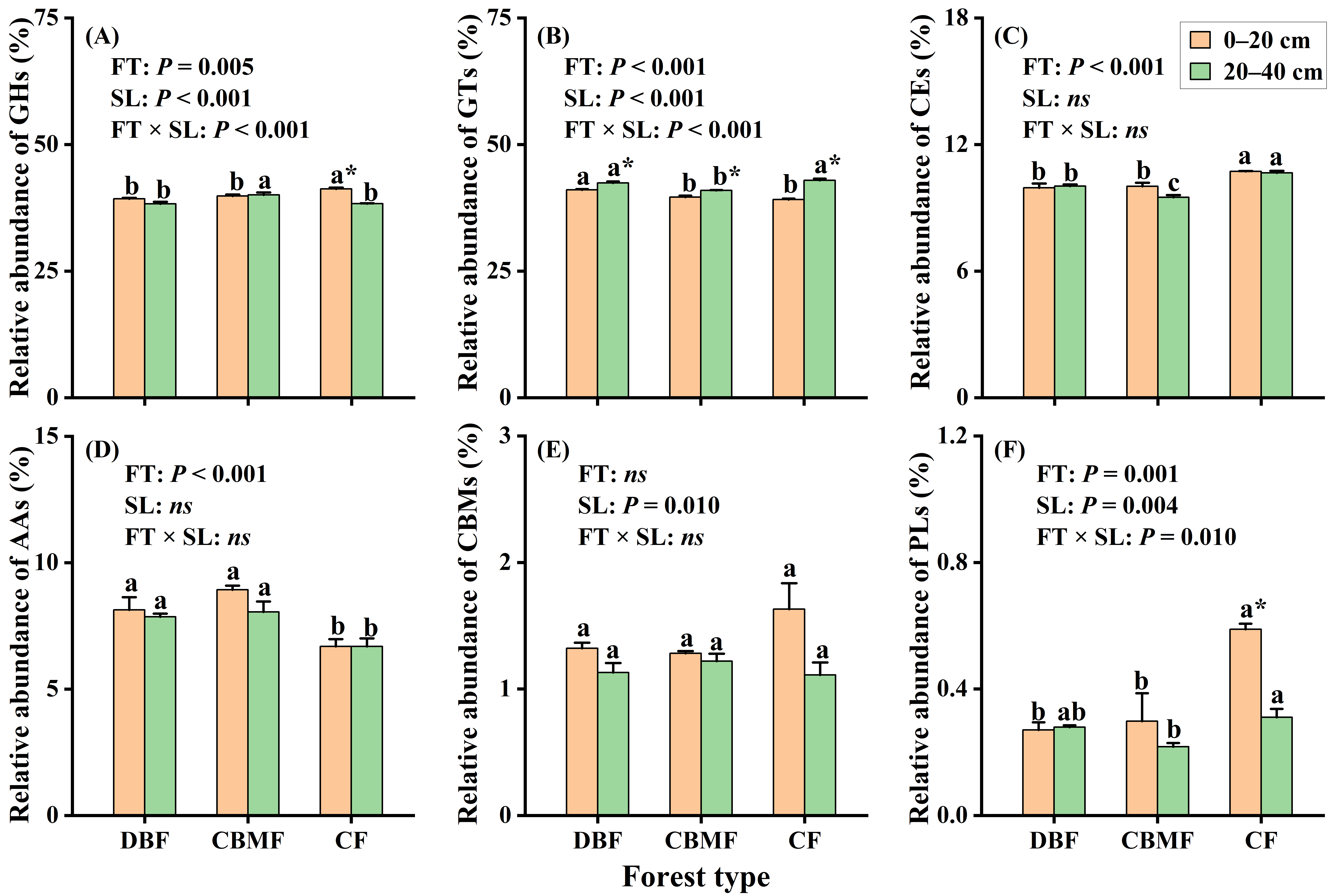

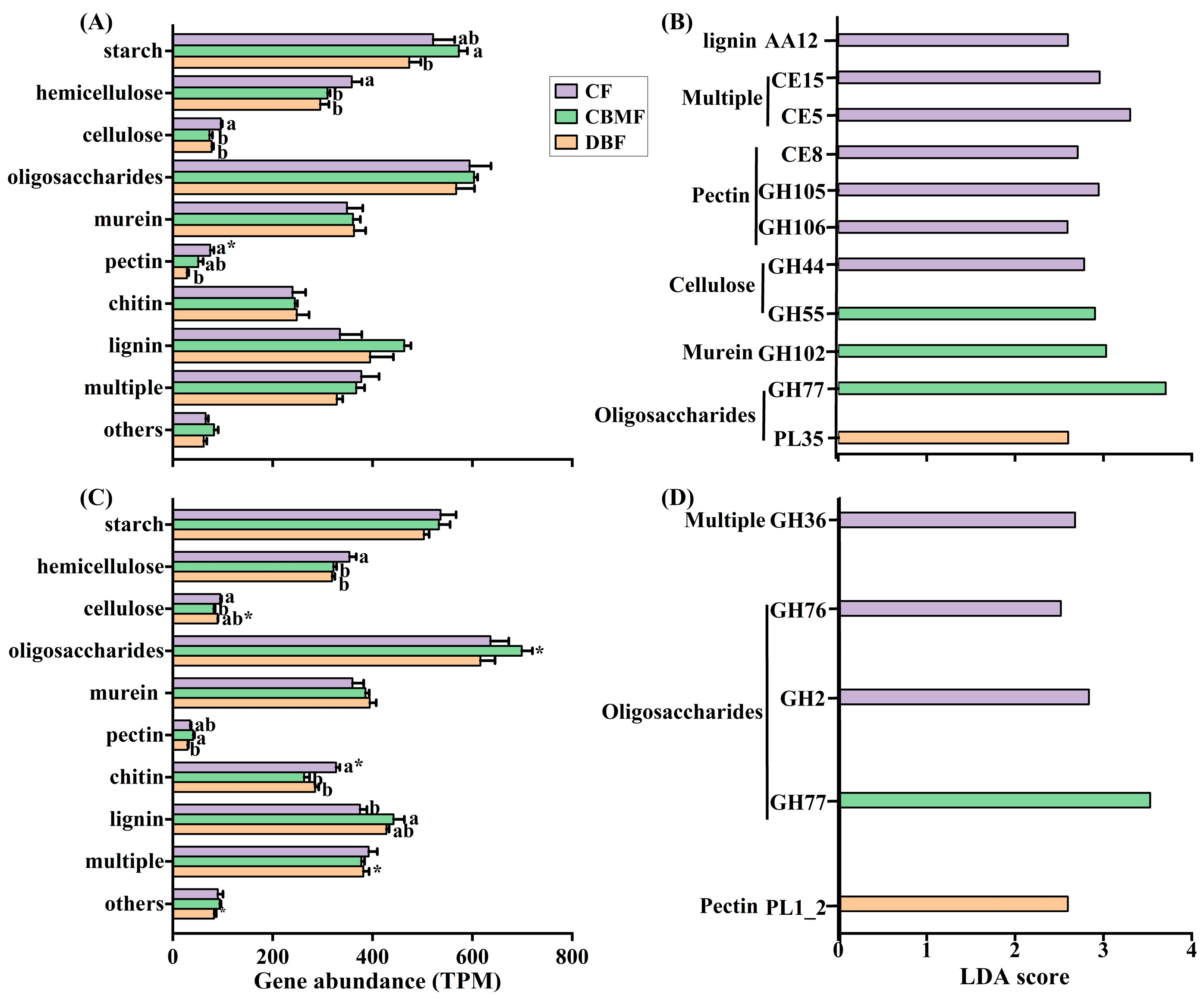

3.4. Carbohydrate Active Enzyme Genes

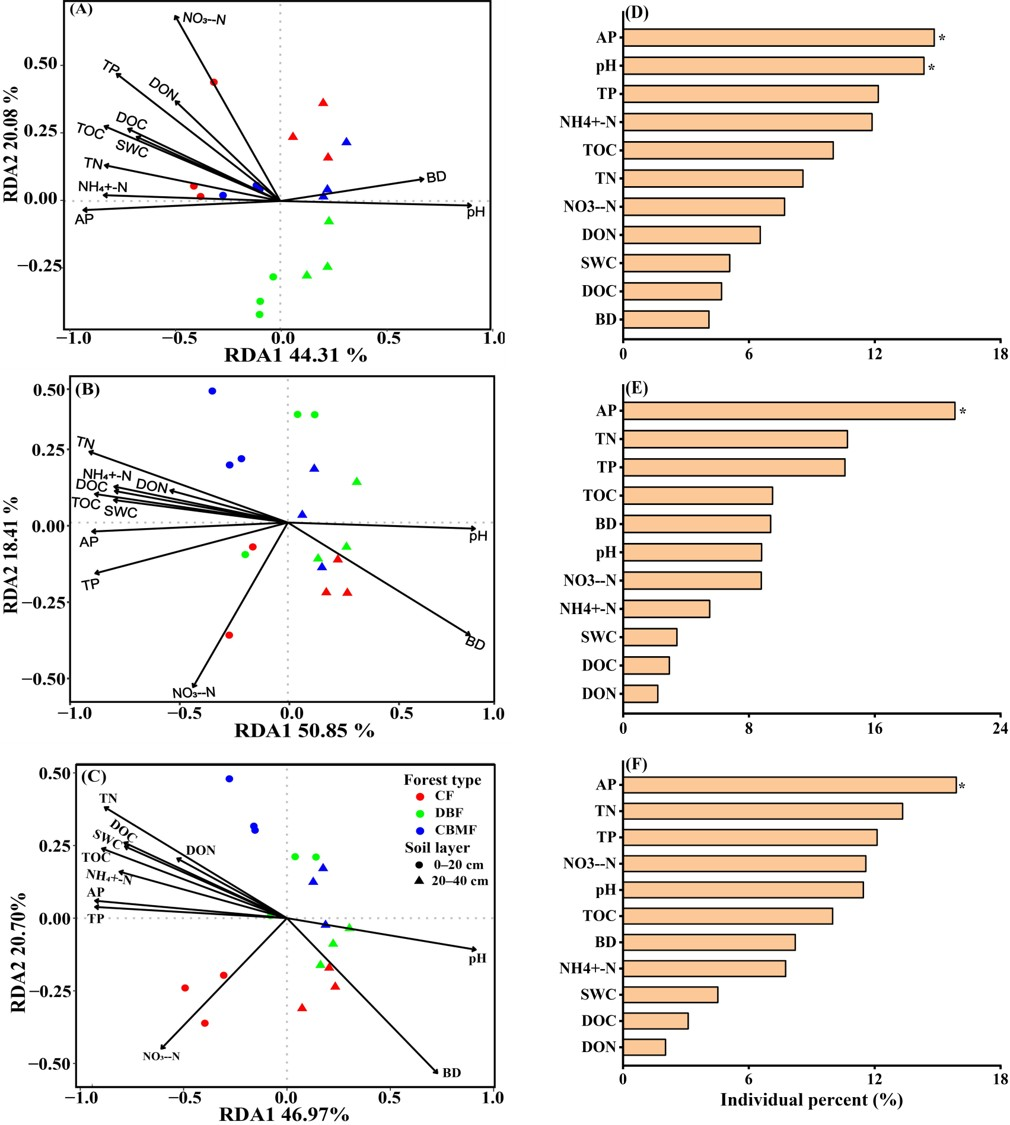

3.5. Relationships Between Microbial Community, Carbon Function Genes, and Soil Properties

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Shvidenko, A.; Lewis, S.L.; Canadell, J.G. A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science 2011, 333, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagadesh, M.; Dash, M.; Singh, S.K.; Kumari, A.; Garg, V.K.; Jaiswal, A. Carbon sequestration potential of forests and forest soils and their role in climate change mitigation. In Forests and Climate Change; Singh, H., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Yan, W.; Wang, R.; Wang, W.; Shangguan, Z. Decreased occurrence of carbon cycle functions in microbial communities along with long-term secondary succession. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 123, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Guo, J.; Suo, R.; Jin, Y.; Li, S.; Zheng, J.; Liu, N.; Han, G.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, B. Light grazing reduces the abundance of carbon cycling functional genes by decreasing oligotrophs microbes in desert steppe. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 199, 105429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tariq, A.; Zeng, F.; Li, X.; Sardans, J.; Al-Bakre, D.A.; Peñuelas, J. Metagenomics reveals divergent functional profiles of soil carbon and nitrogen cycles in an experimental drought and phosphorus-poor desert ecosystem. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 207, 105946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.K.; Gadnayak, A.; Chakraborty, H.J.; Pradhan, S.P.; Raut, S.S.; Das, S.K. Exploring microbial players for metagenomic profiling of carbon cycling bacteria in sundarban mangrove soils. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mondéjar, R.; Tláskal, V.; Větrovský, T.; Štursová, M.; Toscan, R.; Nunes da Rocha, U.; Baldrian, P. Metagenomics and stable isotope probing reveal the complementary contribution of fungal and bacterial communities in the recycling of dead biomass in forest soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 107875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Wang, B.; Shen, J.; Xu, F.; Li, N.; Jia, P.; Jia, Y.; An, S.; Amoah, I.D.; Huang, Y. Shifts in C-degradation genes and microbial metabolic activity with vegetation types affected the surface soil organic carbon pool. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 192, 109371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Sun, L.; Li, J.; Liang, C.; Wei, F.; Xue, S.; Wang, G. Change in composition and potential functional genes of soil bacterial and fungal communities with secondary succession in Quercus liaotungensis forests of the Loess Plateau, western China. Geoderma 2020, 364, 114199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.Q.; Wu, Y.H.; Bing, H.J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.P. Vegetation type rather than climate modulates the variation in soil enzyme activities and stoichiometry in subalpine forests in the eastern Tibetan Plateau. Geoderma 2020, 374, 114424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Lv, D.; Jiang, S.; Lin, H.; Sun, J.; Li, K.; Sun, J. Soil salinity regulation of soil microbial carbon metabolic function in the Yellow River Delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 148258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhou, S.; Xiong, X.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Meng, Z.; Hui, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Deng, Q. Dynamics of soil microbial communities involved in carbon cycling along three successional forests in southern China. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1326057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Maestre, F.T.; Reich, P.B.; Jeffries, T.C.; Gaitan, J.J.; Encinar, D.; Berdugo, M.; Campbell, C.D.; Singh, B.K. Microbial diversity drives multifunctionality in terrestrial ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleuss, P.M.; Widdig, M.; Heintz-Buschart, A.; Guhr, A.; Martin, S.; Kirkman, K.; Spohn, M. Stoichiometric controls of soil carbon and nitrogen cycling after long-term nitrogen and phosphorus addition in a Mesic grassland in South Africa. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, L.; Craven, D.; Jakovac, C.C.; Van Der Sande, M.T.; Amissah, L.; Bongers, F.; Chazdon, R.L.; Farrior, C.E.; Kambach, S.; Meave, J.A.J.S. Multidimensional tropical forest recovery. Science 2021, 374, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Duan, P.; Yang, X.; Li, D. Tree species diversity enhances dark microbial CO2 fixation rates in soil of a subtropical forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 21, 109966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.; Gilbert, J.; Meyer, F. Metagenomics-a guide from sampling to data analysis. Microbial. Inform. Experim 2012, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Yan, M.; Wong, M.H.; Mo, W.Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.W.; Wang, J.J. Effects of biochar on soil microbial community and functional genes of a landfill cover three years after ecological restoration. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 137133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Xiao, T.; Bai, T.; Mo, X.; Huang, J.; Deng, W.; Liu, Y. Seasonal dynamics and influencing factors of litterfall production and carbon input in typical forest community types in Lushan Mountain, China. Forests 2023, 14, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Kang, H.; Pumpanen, J.; Zhu, P.; Liu, C.J.E.R. Soil organic carbon stock and chemical composition along an altitude gradient in the Lushan Mountain, subtropical China. Ecol. Res. 2014, 29, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Shen, Z. Spatial distribution characteristics of soil organic carbon in subtropical forests of mountain Lushan, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Tan, S.; Wang, A.; Chen, W.; Huang, Q. Deciphering belowground nitrifier assemblages with elevational soil sampling in a subtropical forest ecosystem (Mount Lu, China). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2019, 96, fiz197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Mon, C.; Qi, W.; Vikram, S.; Frossard, A.; Makhalanyane, T.; Cowan, D.; Frey, B. Shotgun metagenomics reveals distinct functional diversity and metabolic capabilities between 12000-year-old permafrost and active layers on Muot da Barba Peider (Swiss Alps). Microb. Genom. 2021, 7, 000558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frey, B.; Varliero, G.; Qi, W.; Stierli, B.; Walthert, L.; Brunner, I. Shotgun metagenomics of deep forest soil layers show evidence of altered microbial genetic potential for biogeochemical cycling. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 828977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Sun, Z.; Bai, W.; Feng, C.; Risch, A.C.; Feng, L.; Frey, B. Maize–peanut intercropping and N fertilization changed the potential nitrification rate by regulating the ratio of AOB to AOA in soils. Clim. Smart Agri 2024, 1, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, R.; Duggal, G.; Love, M.I.; Irizarry, R.A.; Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Xu, M.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Han, X.; Zhao, F.; Yang, G.; et al. Altered microbial CAZyme families indicated dead biomass decomposition following afforestation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 16, 108362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.K. Methods for Agricultural Chemical Analysis of Soil; China Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 1999. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.W.; Fan, M.X.; Qin, H.Y.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Liu, S.J.; Wu, S.W.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, X. Interactions between morel cultivation, soil microbes, and mineral nutrients: Impacts and mechanisms. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, R.H.; Kurtz, L.T. Determination of total, organic and available forms of P in soils. Soil Sci. 1945, 59, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, D.; Jin, S.F.; Wu, J.P. Soil bacterial community is more sensitive than fungal community to canopy nitrogen deposition and understory removal in a Chinese fir plantation. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1015936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Peres-Neto, P.R. Generalizing hierarchical and variation partitioning in multiple regression and canonical analyses using the rdacca.hp R package. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2022, 13, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibe, A.; Steffens, C.; Seven, J.; Jacob, A.; Hertel, D.; Leuschner, C.; Gleixner, G. Effects of tree identity dominate over tree diversity on the soil microbial community structure. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 81, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, B.M.; Kim, M.; Kim, Y.; Byun, E.; Yang, J.W.; Ahn, J.; Lee, Y.K. Variations in bacterial and archaeal communities along depth profiles of Alaskan soil cores. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, E.Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.D.; Yan, Z.Q.; Wu, H.D.; Li, M.; Yan, L.; Zhang, K.R.; Wang, J.Z.; Kang, X.M. Soil pH and nutrients shape the vertical distribution of microbial communities in an alpine wetland. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Bai, M.; Chen, Y.; Guo, J.; Chen, L. Environmental effects on bacterial community assembly in arid and semi-arid grasslands. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cline, L.C.; Hobbie, S.E.; Madritch, M.D.; Buyarski, C.R.; Tilman, D.; Cavender-Bares, J.M. Resource availability underlies the plant-fungal diversity relationship in a grassland ecosystem. Ecology 2018, 99, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.J.; Shen, C.C.; Wu, H.Y.; Zhang, L.M.; Wang, J.C.; Liu, S.Y.; Jing, Z.W.; Ge, Y. Environmental selection dominates over dispersal limitation in shaping bacterial biogeographical patterns across different soil horizons of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yan, X.; Gao, E.; Qiu, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Bruun, H.H.; He, Z.; Shi, X. Changes in composition and function of soil microbial communities during secondary succession in oldfields on the Tibetan Plateau. Plant Soil 2024, 495, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Liu, X.; Song, L.; Lin, X.; Zhang, H.; Shen, C.; Chu, H. Nitrogen fertilization directly affects soil bacterial diversity and indirectly affects bacterial community composition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 92, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldrop, M.P.; Holloway, J.; Smith, D.B.; Goldhaber, M.B.; Drenovsky, R.E.; Scow, K.; Dick, R.; Howard, D.; Wylie, B.; Grace, J.B. The interacting roles of climate, soils, and plant production on soil microbial communities at a continental scale. Ecology 2017, 98, 1957–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauber, C.L.; Hamady, M.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 5111–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, E.; Luo, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Chen, C.; Lu, X.; Jiang, L.; Luo, X.; Wen, D. Global meta-analysis shows pervasive phosphorus limitation of aboveground plant production in natural terrestrial ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Crowther, T.W.; Isobe, K.; Reich, P.B.; Tateno, R.; Shi, W. Metagenomic insights into inhibition of soil microbial carbon metabolism by phosphorus limitation during vegetation succession. ISME Commun. 2024, 4, ycae128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, L.; Liu, L.; Gao, C.; Chen, B.; Xu, D.; Liu, J.; He, Z. Soil phosphorus availability controls deterministic and stochastic processes of soil microbial community along an elevational gradient in subtropical forests. Forests 2023, 14, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widdig, M.; Heintz-Buschart, A.; Schleuss, P.M.; Guhr, A.; Borer, E.T.; Seabloom, E.W.; Spohn, M. Effects of nitrogen and phosphorus addition on microbial community composition and element cycling in a grassland soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 108041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, T.M.; Ge, T.; Yuan, H.; Wei, X.; Wu, X.; Xiao, K.; Kumaresan, D.; Yu, S.; Wu, J.; Whiteley, A.S. Soil carbon-fixation rates and associated bacterial diversity and abundance in three natural ecosystems. Microb. Ecol. 2017, 73, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Ge, T.; Wu, X.; Peacock, C.L.; Zhu, Z.; Peng, J.; Bao, P.; Wu, J.; Zhu, Y. Metagenomic and 14C tracing evidence for autotrophic microbial CO2 fixation in paddy soils. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Gong, L.; Ding, Z.; Zhu, H.; Tang, J.; Li, X. Changes in soil microbial carbon fixation pathways along the oasification process in arid desert region: A confirmation based on metagenome analysis. Catena 2024, 239, 107955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassens, N.J.; Sousa, D.Z.; Dos Santos, V.A.M.; De Vos, W.M.; van der Oost, J. Harnessing the power of microbial autotrophy. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, N.H.; Farag, I.F.; Rudy, S.; Mulliner, A.; Walker, K.; Caldwell, F.; Miller, M.; Hoff, W.; Elshahed, M. The wood-ljungdahl pathway as a key component of metabolic versatility in candidate phylum bipolaricaulota (Acetothermia, OP1). Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2019, 11, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Jing, H.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, Y. Insights into carbon-fixation pathways through metagonomics in the sediments of deep-sea cold seeps. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 176, 113458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Zang, H.; Chen, J.; Fu, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Shen, C.; Wang, J.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Becker, J.N.; et al. Metagenomic insights into soil microbial communities involved in carbon cycling along an elevation climosequences. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 4631–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, S.T.C.; Freund, H.L.; Kasanjian, J.; Berlemont, R. Function, distribution, and annotation of characterized cellulases, xylanases, and chitinases from CAZy. Appl. Microbiol. Biotech. 2018, 102, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, M.; Ding, Y.; Deng, D.; Lai, Z.; Long, W. The contributions of dark microbial CO2 fixation to soil organic carbon along a tropical secondary forest chronosequence on Hainan Island, China. Catena 2024, 247, 108556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, S.; Lu, M.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H. Identifying bacterial fixation pathway of mediating soil carbon stock changes along tropical forest restoration. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 20, 105792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Hill, B.H.; Follstad Shah, J.J. Ecoenzymatic stoichiometry of microbial organic nutrient acquisition in soil and sediment. Nature 2009, 462, 795–798, Erratum in Nature 2010, 468, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Peng, C.; Kim, D.G.; Jiang, L.; Liu, Y.; Hai, X.; Liu, Q.; Huang, C.; Shang, G.Z.; Kuzyakov, Y. Drought effects on soil carbon and nitrogen dynamics in global natural ecosystems. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 104, 103501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Properties | DBF | CBMF | CF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–20 cm | 20–40 cm | 0–20 cm | 20–40 cm | 0–20 cm | 20–40 cm | |

| BD (g cm−3) | 0.85 ± 0.03 a | 0.92 ± 0.02 a | 0.71 ± 0.03 a | 0.93 ± 0.02 b* | 0.79 ± 0.04 a | 1.05 ± 0.02 a* |

| pH | 4.67 ± 0.02 a | 4.83 ± 0.01 a* | 4.53 ± 0.02 b | 4.88 ± 0.04 a* | 4.43 ± 0.02 c | 4.88 ± 0.03 a* |

| SWC (%) | 32.0 ± 0.32 a* | 26.7 ± 0.92 a | 33.5 ± 0.68 a* | 30.0 ± 1.05 a | 35.5 ± 2.1 a* | 27.9 ± 1.8 a |

| TOC (g kg−1) | 27.47 ± 1.27 b* | 11.63 ± 0.42 b | 44.55 ± 2.31 a* | 19.07 ± 0.73 a | 46.52 ± 2.53 a* | 20.79 ± 1.48 a |

| TN (g kg−1) | 2.28 ± 0.09 b* | 0.96 ± 0.04 b | 3.55 ± 0.13 a* | 1.45 ± 0.03 a | 3.23 ± 0.23 a* | 1.30 ± 0.11 a |

| TP (g kg−1) | 0.25 ± 0.01 b* | 0.08 ± 0.01 b | 0.38 ± 0.01 a* | 0.26 ± 0.01 a | 0.43 ± 0.03 a* | 0.25 ± 0.01 a |

| NH4+-N (mg kg−1) | 2.62 ± 0.09 b* | 1.45 ± 0.25 a | 2.68 ± 0.07 b* | 1.31 ± 0.06 a | 3.34 ± 0.27 a* | 1.48 ± 0.2 a |

| NO3−-N (mg kg−1) | 1.83 ± 0.10 c | 1.58 ± 0.34 c | 4.01 ± 0.51 b* | 2.22 ± 0.33 b | 7.08 ± 0.34 a | 5.6 ± 0.52 a |

| AP (mg kg−1) | 1.38 ± 0.25 b* | 0.23 ± 0.09 a | 1.4 ± 0.10 b* | 0.21 ± 0.06 a | 2.51 ± 0.14 a* | 0.28 ± 0.06 a |

| DON (mg kg−1) | 26.97 ± 1.36 a* | 14.53 ± 1.57 a | 29.37 ± 1.95 a* | 21.42 ± 1.7 a | 28.51 ± 1.51 a | 25.9 ± 3.39 a |

| DOC (mg kg−1) | 301.5 ± 4.0 b* | 131.6 ± 15.3 b | 368.4 ± 8.7 a* | 232.9 ± 5.5 a | 385.2 ± 22.7 a* | 233.6 ± 30.0 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xi, D.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, J. Forest Type Shapes Soil Microbial Carbon Metabolism: A Metagenomic Study of Subtropical Forests on Lushan Mountain. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010220

Xi D, Zhu F, Zhang Z, Zhou S, Zhang J. Forest Type Shapes Soil Microbial Carbon Metabolism: A Metagenomic Study of Subtropical Forests on Lushan Mountain. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):220. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010220

Chicago/Turabian StyleXi, Dan, Feifei Zhu, Zhaochen Zhang, Saixia Zhou, and Jiaxin Zhang. 2026. "Forest Type Shapes Soil Microbial Carbon Metabolism: A Metagenomic Study of Subtropical Forests on Lushan Mountain" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010220

APA StyleXi, D., Zhu, F., Zhang, Z., Zhou, S., & Zhang, J. (2026). Forest Type Shapes Soil Microbial Carbon Metabolism: A Metagenomic Study of Subtropical Forests on Lushan Mountain. Microorganisms, 14(1), 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010220