Oral Microbiome Dynamics in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Oral Mucositis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Oral Examination and Grading of OM

- Grade 0: No mucositis;

- Grade 1: Soreness/erythema;

- Grade 2: Erythema and ulcers; able to tolerate solid food;

- Grade 3: Unable to tolerate solid food, but able to tolerate liquids;

- Grade 4: Unable to tolerate solids or liquids; oral alimentation is not possible.

2.3. Oral Sample Collection

2.4. Microbiome Analyses—DNA Extraction, 16S rRNA PCR Amplification and Sequencing

2.5. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.6. Detection of Interleukins

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Alpha and Beta Diversity on Days 0, 14 and 21 of CTX and in Patients Who Did or Did Not Develop Oral Mucositis

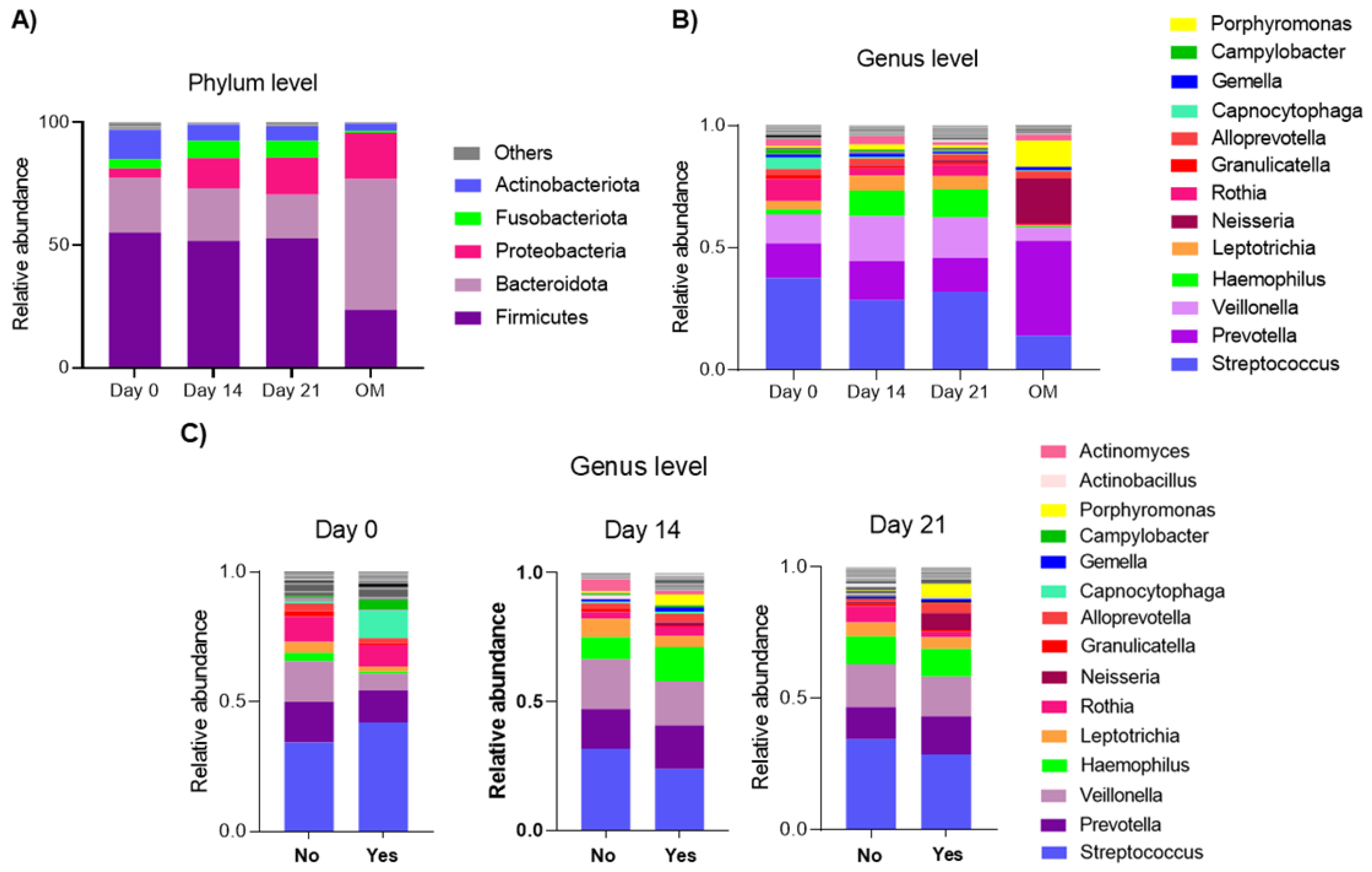

3.2. Relative Abundance on Days 0, 14 and 21 of CTX and in Patients Who Did or Did Not Develop Oral Mucositis

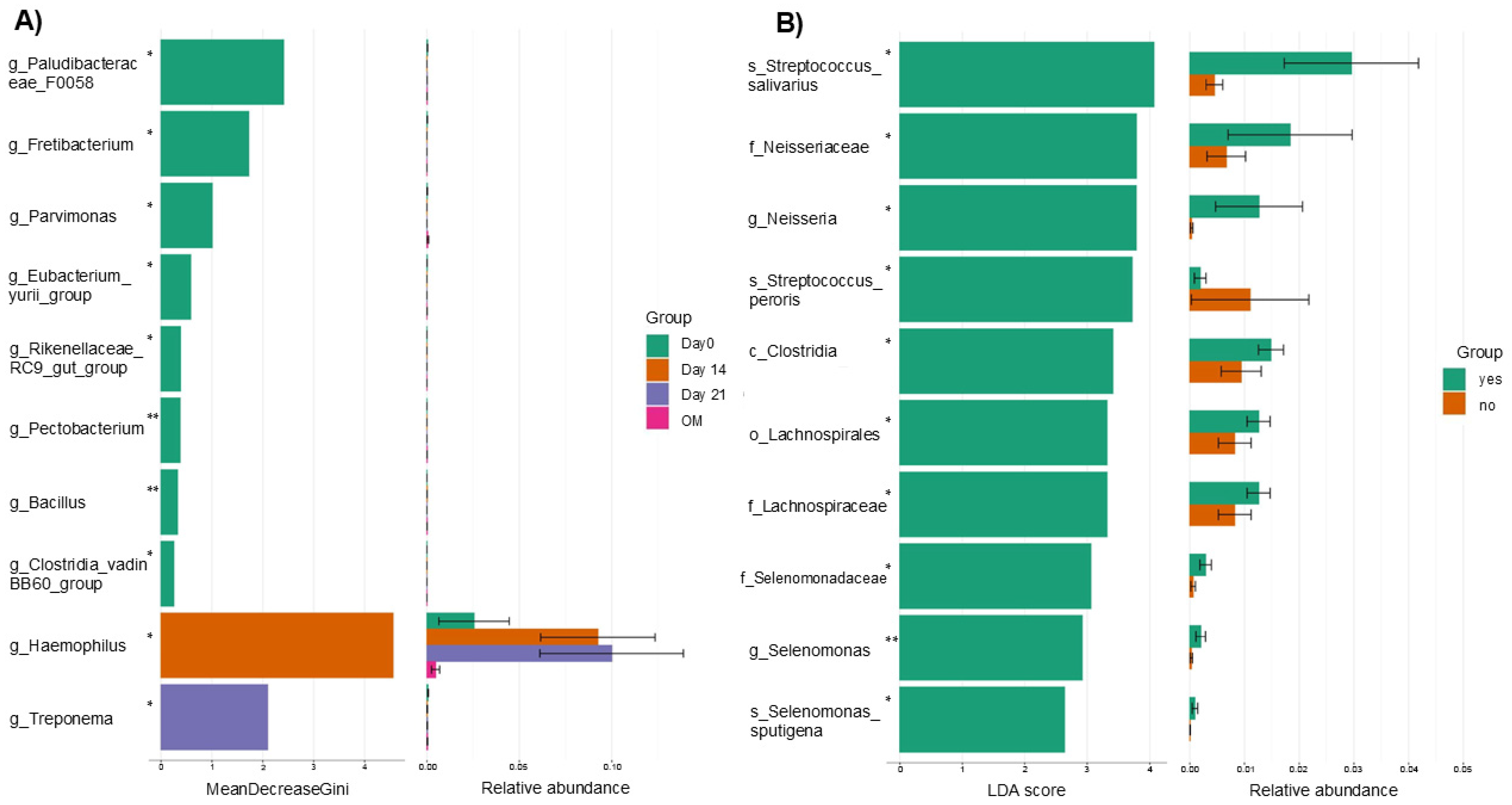

3.3. Differential Abundance on Days 0, 14 and 21 of CTX and in Patients Who Did or Did Not Develop Oral Mucositis

3.4. Cytokine Profile in Saliva in Patients with ALL on Days 0, 14 and 21 of CTX and in Patients Who Experienced OM During Subsequent Phases of CTX vs. Children Who Never Developed OM

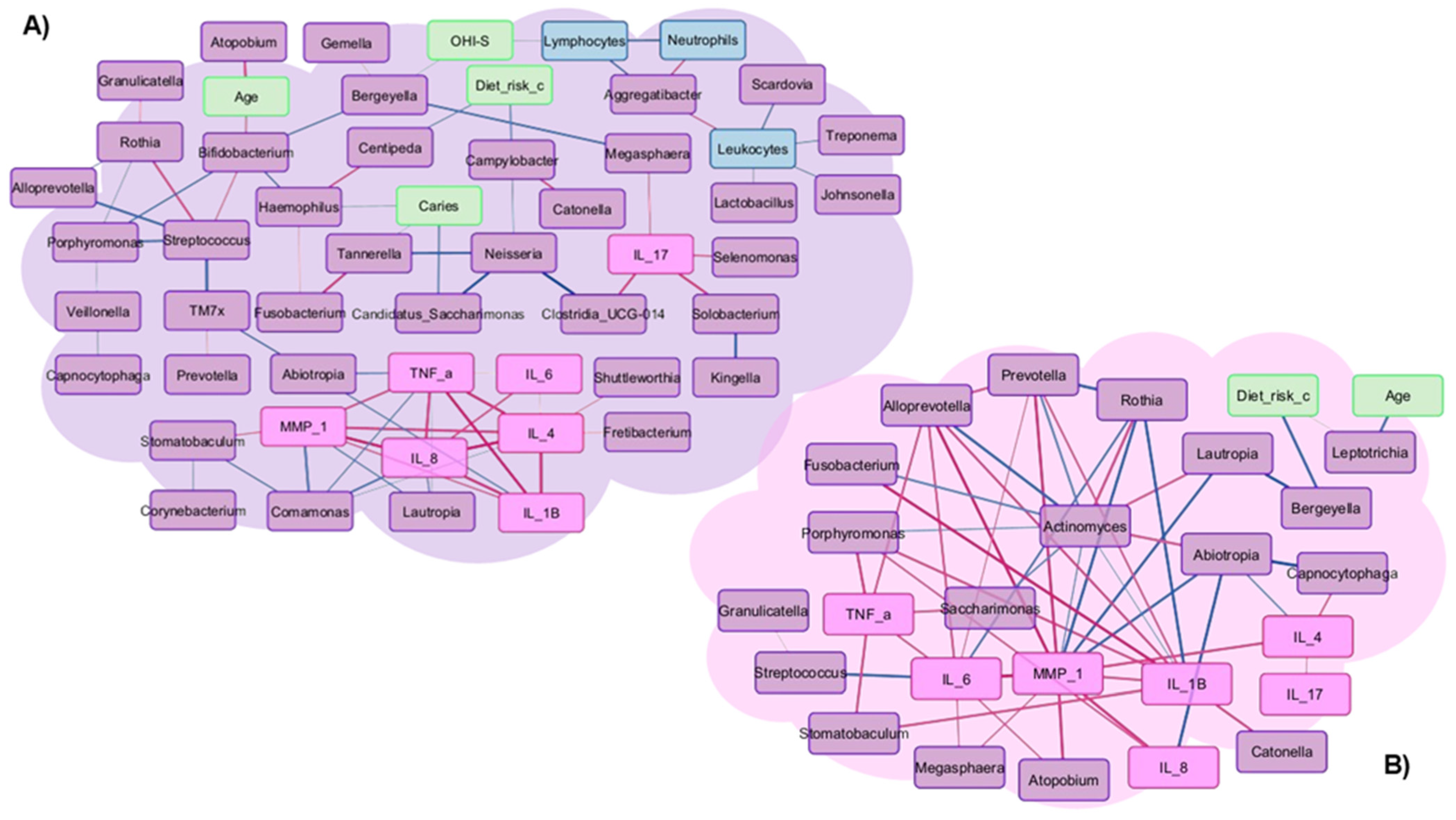

3.5. Correlations in Patients Who Did or Did Not Develop Oral Mucositis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALL | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| CTX | Chemotherapy |

| OM | Oral mucositis |

| IL | Interleukin |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| TNF-α | Tumoral necrosis factor alpha |

| OHI-S | Oral hygiene index |

| ICDAS | International Caries Detection and Assessment System |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PCoA | Principal coordinate analysis |

| RA | Relative abundance |

| KW | Kruskal–Wallis |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

References

- Bustamante, J.C.; Hernández, A.; Galván, C.; Rivera, R.; Fuentes, H.E.; Meneses, A.; Olaya, A. Childhood leukemias in Mexico: Towards implementing CAR-T cell therapy programs. Front. Oncol. 2024, 18, 1304805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyomi, A.; Yoshida, K.; Arai, C.; Usuki, R.; Yamazaki, K.; Hoshino, N.; Kurokawa, A.; Imai, S.; Suzuki, N.; Toyama, A.; et al. Salivary inflammatory mediators as biomarkers for oral mucositis and oral mucosal dryness in cancer patients: A pilot study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B.Y.; Sobue, T.; Choquette, L.; Dupuy, A.K.; Thompson, A.; Burleson, J.A.; Salner, A.L.; Schauer, P.K.; Joshi, P.; Fox, E.; et al. Chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis is associated with detrimental bacterial dysbiosis. Microbiome 2019, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakim, H.; Dallas, R.; Wolf, J.; Tang, L.; Schultz-Cherry, S.; Darling, V.; Johnson, C.; Karlsson, E.A.; Chang, T.-C.; Jeha, S.; et al. Gut Microbiome Composition Predicts Infection Risk During Chemotherapy in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonis, S.T. Oral mucositis in head and neck cancer: Risk, biology, and management. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2013, 33, e236–e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basile, D.; Di Nardo, P.; Corvaja, C.; Garattini, S.K.; Pelizzari, G.; Lisanti, C.; Bortot, L.; Da Ros, L.; Bartoletti, M.; Borghi, M.; et al. Mucosal Injury during Anti-Cancer Treatment: From Pathobiology to Bedside. Cancers 2019, 11, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, A.S.; Kong, E.F.; Rizk, A.M.; Jabra-Rizk, M.A. The oral microbiome: A Lesson in coexistence. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinausero, M.; Aprile, G.; Ermacora, P.; Basile, D.; Vitale, M.G.; Fanotto, V.; Parisi, G.; Calvetti, L.; Sonis, S.T. New Frontiers in the Pathobiology and Treatment of Cancer Regimen-Related Mucosal Injury. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.; Koc, A.; Dogru, O.; Tufan Tas, B.; Senay, R.E. The results of the modified St Jude Total Therapy XV Protocol in the treatment of low- and middle-income children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2023, 64, 1304–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.C.; Vermillion, J.R. The Simplified Oral Hygiene Index. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1964, 68, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, N. “ICDAS”—An international system for caries detection and assessment being developed to facilitate caries epidemiology, research and appropriate clinical management. Community Dent. Health 2004, 21, 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Handbook for Reporting Results of Cancer Treatment; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1979; Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/c1b590fa-20a6-4c97-9123-5cc4d34c7cdb/content (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857, Erratum in Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1091.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar]

- Triarico, S.; Agresti, P.; Rinninella, E.; Mele, M.C.; Romano, A.; Attinà, G.; Maurizi, P.; Mastrangelo, S.; Ruggiero, A. Oral Microbiota during Childhood and Its Role in Chemotherapy-Induced Oral Mucositis in Children with Cancer. Pathogens 2022, 11, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khor, B.; Snow, M.; Herrman, E.; Ray, N.; Mansukhani, K.; Patel, K.A.; Said-Al-Naief, N.; Maier, T.; Machida, C.A. Interconnections Between the Oral and Gut Microbiomes: Reversal of Microbial Dysbiosis and the Balance Between Systemic Health and Disease. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xue, J.; Zhou, X.; You, M.; Du, Q.; Yang, X.; He, J.; Zou, J.; Cheng, L.; Li, M.; et al. Oral microbiota distinguishes acute lymphoblastic leukemia pediatric hosts from healthy populations. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102116, Correction in PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110449.. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Yang, X.; Que, J.; Du, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, J. Oral Health, Caries Risk Profiles, and Oral Microbiome of Pediatric Patients with Leukemia Submitted to Chemotherapy. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6637503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, A.K.; Vogtmann, E.; Shi, J.; Yano, Y.; Blaser, M.J.; Bokulich, N.A.; Caporaso, J.G.; Gillison, M.L.; Graubard, B.I.; Hua, X.; et al. The mouth of America: The oral microbiome profile of the US population. medRxiv, 2024; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Carlsson, G.; Agholme, M.B.; Wilson, J.A.; Roos, A.; Henriques-Normark, B.; Engstrand, L.; Modéer, T.; Pütsep, K. Oral bacterial community dynamics in paediatric patients with malignancies in relation to chemotherapy-related oral mucositis: A prospective study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, E559–E567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzaczek, P.M.; Mitura-Lesiuk, M.; Zawitkowska, J.; Petkowicz, B.; Wilczyńska, B.; Drabko, K. Salivary and serum concentrations of selected pro- and antiinflammatory cytokines in relation to oral lesions among children undergoing maintenance therapy of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Contemp. Oncol. Pozn 2019, 23, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, R.; Sanfilippo, N.; Paster, B.; Kerr, A.; Li, Y.; Ramalho, L.; Queiroz, E.; Smith, B.; Sonis, S.; Corby, P. Hostmicrobiome cross-talk in oral mucositis. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filetici, P.; Gallottini, S.G.; Corvaglia, A.; Amendolea, M.; Sangiovanni, R.; Nicoletti, F.; D’Addona, A.; Dassatti, L. The role of oral microbiota in the development of oral mucositis in pediatric oncology patients treated with antineoplastic drugs: A systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, W.G. Resilience of the oral microbiome. Periodontol. 2000 2021, 86, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamashiro, R.; Strange, L.; Schnackenberg, K.; Santos, J.; Gadalla, H.; Zhao, L.; Li, E.C.; Hill, E.; Hill, B.; Sidhu, G.; et al. Stability of healthy subgingival microbiome across space and time. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway-Peña, J.R.; Smith, D.P.; Sahasrabhojane, P.; Wadsworth, W.D.; Fellman, B.M.; Ajami, N.J.; Shpall, E.J.; Daver, N.; Guindani, M.; Petrosino, J.F.; et al. Characterization of oral and gut microbiome temporal variability in hospitalized cancer patients. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, E.A.; Duggal, M.S.; Bailey, C.C.; Curzon, M.E.; Hart, P. Changes in the oral microflora during cytotoxic chemotherapy in children being treated for acute leukemia. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1993, 76, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, K.; Chen, T.; Paster, B.J. A practical guide to the oral microbiome and its relation to health and disease. Oral Dis. 2017, 23, 276–286. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, N.; Bhatia, S.; Sodhi, A.S.; Batra, N. Oral microbiome and health. AIMS Microbiol. 2018, 4, 42–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Fuentes, M.E.; Pérez-Sayáns, M.; Chauca-Bajaña, L.A.; Barbeito-Castiñeiras, G.; Molino-Bernal, M.L.; López-López, R. Oral microbiome and systemic antineoplastics in cancer treatment: A systematic review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cirugia Bucal 2022, 27, e248–e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, J.S.; Al-Qadami, G.H.; Laheij, A.M.G.A.; Bossi, P.; Fregnani, E.R.; Wardill, H.R. From Pathogenesis to Intervention: The Importance of the Microbiome in Oral Mucositis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcham, Z.M.; Garneau, N.L.; Comstock, S.S.; Tucker, R.M.; Knight, R.; Metcalf, J.L. Genetics of Taste Lab Citizen Scientists. Patterns of Oral Microbiota Diversity in Adults and Children: A Crowdsourced Population Study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2133. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhry, A.; Kapoor, P.; Bhargava, D.; Bagga, D.K. Exploring the oral microbiome: An updated multidisciplinary oral healthcare perspective. Discov. Craiova 2023, 11, e165. [Google Scholar]

- Crielaard, W.; Zaura, E.; Schuller, A.A.; Huse, S.M.; Montijn, R.C.; Keijser, B.J. Exploring the oral microbiota of children at various developmental stages of their dentition in the relation to their oral health. BMC Med. Genom. 2011, 4, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Haakensen, M.; Dobson, C.M.; Deneer, H.; Ziola, B. Real-time PCR detection of bacteria belonging to the Firmicutes Phylum. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 125, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Fiscella, K.A.; Gill, S.R. Oral microbiome: Possible harbinger for children’s health. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhoecke, B.; De Ryck, T.; Stringer, A.; Van de Wiele, T.; Keefe, D. Microbiota and their role in the pathogenesis of oral mucositis. Oral Dis. 2015, 21, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baty, J.J.; Stoner, S.N.; Scoffield, J.A. Oral Commensal Streptococci: Gatekeepers of the Oral Cavity. J. Bacteriol. 2022, 204, e0025722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaura, E.; Keijser, B.J.; Huse, S.M.; Crielaard, W. Defining the healthy “core microbiome” of oral microbial communities. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, A.S.; Nexoe, A.B.; Dubik, M.; Moeller, J.B.; Soerensen, G.L.; Holmskov, U.; Madsen, G.I.; Husby, S.; Rathe, M. Peptidoglycan Recognition Peptide 2 Aggravates Weight Loss in a Murine Model of Chemotherapy-Induced Gastrointestinal Toxicity. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 635005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.F.; Fermiano, D.; Feres, M.; Figueiredo, L.C.; Teles, F.R.; Mayer, M.P.; Faveri, M. Levels of Selenomonas species in generalized aggressive periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2012, 47, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, C.G.; Hinson, A.N.; Vashishta, A.; Read, C.B.; Carlyon, J.A.; Lamont, R.J.; Uriarte, S.M.; Miller, D.P. Selenomonas sputigena Interactions with Gingival Epithelial Cells That Promote Inflammation. Infect. Immun. 2023, 91, e0031922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isabel, R. Capnocytophaga sputigena bacteremia in a neutropenic host. IDCases 2019, 17, e00536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, F.R.; Bruniera, F.R.; Schmidt, J.; Cury, A.P.; Rizeck, C.; Higashino, H.; Oliveira, F.N.; Rossi, F.; Rocha, V.; Costa, S.F. Capnocytophaga sputigena bloodstream infection in hematopoietic stem cell transplantations: Two cases report and review of the literature. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2020, 62, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, R.; Rámila, E.; Capdevila, J.A.; Planes, A.; Rovira, M.; Ortega, M.d.M.; Plumé, G.; Gómez, L.; Sierra, J. Bacteremia caused by Capnocytophaga species in patients with neutropenia and cancer: Results of a multicenter study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, E20–E22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Rong, X.; Wang, W.; Liang, L.; Liao, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, W.; Liu, W.; Shi, L. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Chemotherapy-Induced Oral Mucositis in 470 Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2025, 35, 888–897. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.W.; Xu, P.; Cai, L.T.; Tan, Z.W.; Guo, Y.T.; Zhu, R.X.; He, Y. The presence of Prevotella melaninogenica within tissue and preliminary study on its role in the pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2022, 28, 1580–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Cui, Q.; An, R.; Wang, J.; Song, X.; Shen, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, H. Comparison of microbiomes in ulcerative and normal mucosa of recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS)-affected patients. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rojas, T.; Viera, N.; Morón-Medina, A.; Alvarez, C.J.; Alvarez, A. Proinflammatory cytokines during the initial phase of oral mucositis in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2012, 22, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Radaic, A.; Ganther, S.; Kamarajan, P.; Grandis, J.; Yom, S.S.; Kapila, Y.L. Paradigm shift in the pathogenesis and treatment of oral cancer and other cancers focused on the oralome and antimicrobial-based therapeutics. Periodontol. 2000 2021, 87, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Wang, P.; Liu, Z.H.; Ye, P. Analysis of differential expression of tight junction proteins in cultured oral epithelial cells altered by Porphyromonas gingivalis, Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide, and extracellular adenosine triphosphate. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 10, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hintermann, E.; Haake, S.K.; Christen, U.; Sharabi, A.; Quaranta, V. Discrete proteolysis of focal contact and adherens junction components in Porphyromonas gingivalis-infected oral keratinocytes: A strategy for cell adhesion and migration disabling. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 5846–5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksijević, L.H.; Aleksijević, M.; Škrlec, I.; Šram, M.; Šram, M.; Talapko, J. Porphyromonas gingivalis Virulence Factors and Clinical Significance in Periodontal Disease and Coronary Artery Diseases. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, D.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S.; Pan, Y. The Role of Porphyromonas gingivalis Outer Membrane Vesicles in Periodontal Disease and Related Systemic Diseases. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 10, 585917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, M.; Naito, M.; Omori, K.; Ono, S.; Nakayama, K.; Ohara, N. Porphyromonas gingivalis Gingipains Induce Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression and Prostaglandin E2 Production via ERK1/2-Activated AP-1 (c-Jun/c-Fos) and IKK/NF-κB p65 Cascades. J. Immunol. 2022, 208, 1146–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könönen, E.; Fteita, D.; Gursoy, U.K.; Gursoy, M. Prevotella species as oral residents and infectious agents with potential impact on systemic conditions. J. Oral Microbiol. 2022, 14, 2079814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.G.; Chiu, M.; Taurino, G.; Bergamaschi, E.; Turroni, F.; Mancabelli, L.; Longhi, G.; Ventura, M.; Bussolati, O. Amorphous silica nanoparticles and the human gut microbiota: A relationship with multiple implications. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 45. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | n | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 16 | 50 | |

| Male | 16 | 50 | |

| Total | 32 | 100 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 0–5 | 11 | 34.4 | |

| 6–13 | 12 | 37.5 | |

| +14 | 9 | 28.1 | |

| Total | 32 | 100 | |

| OHI-S | |||

| Poor | 1 | 3.2 | |

| Fair | 17 | 53.1 | |

| Good | 12 | 37.5 | |

| Lost | 2 | 6.2 | |

| Total | 32 | 100 | |

| Dental caries | |||

| 0 | 4 | 12.5 | |

| 1–2 | 4 | 12.5 | |

| 3 | 8 | 25 | |

| 4–5 | 7 | 21.9 | |

| 6 | 7 | 21.9 | |

| Lost | 2 | 6.2 | |

| Total | 32 | 100 | |

| Cariogenic risk of diet | |||

| Low | 14 | 43.7 | |

| Moderate | 14 | 43.7 | |

| High | 2 | 6.2 | |

| Lost | 2 | 6.2 | |

| Total | 32 | 100 | |

| Variable | n | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 5 | 38.5 | |

| Male | 8 | 61.5 | |

| Total | 13 | 100 | |

| Median age (years) | 9 | ||

| Age (years) | |||

| 0–5 | 5 | 38.5 | |

| 6–13 | 5 | 38.5 | |

| +14 | 3 | 23 | |

| Total | 13 | 100 | |

| Development of OM | |||

| Induction | 4 | 30.7 | |

| Consolidation | 7 | 53.8 | |

| Maintenance | 2 | 15.4 | |

| Total | 13 | 100 | |

| Grade of OM | |||

| I | 1 | 7.7 | |

| II | 3 | 23 | |

| III | 1 | 7.7 | |

| IV | 3 | 23 | |

| Not specified | 5 | 38.5 | |

| Total | 13 | 100 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Becerra, A.E.; Peña-Rodríguez, M.; Vega-Magaña, A.N.; García-Arellano, S.; Romo-Rubio, H.A.; Flores-Navarro, S.; Escobedo-Melendez, G.; Aranda-Romo, S.; Zepeda-Nuño, J.S. Oral Microbiome Dynamics in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Oral Mucositis. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010185

Sánchez-Becerra AE, Peña-Rodríguez M, Vega-Magaña AN, García-Arellano S, Romo-Rubio HA, Flores-Navarro S, Escobedo-Melendez G, Aranda-Romo S, Zepeda-Nuño JS. Oral Microbiome Dynamics in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Oral Mucositis. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):185. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010185

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Becerra, Ana Elizabeth, Marcela Peña-Rodríguez, Alejandra Natali Vega-Magaña, Samuel García-Arellano, Hugo Antonio Romo-Rubio, Sony Flores-Navarro, Griselda Escobedo-Melendez, Saray Aranda-Romo, and José Sergio Zepeda-Nuño. 2026. "Oral Microbiome Dynamics in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Oral Mucositis" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010185

APA StyleSánchez-Becerra, A. E., Peña-Rodríguez, M., Vega-Magaña, A. N., García-Arellano, S., Romo-Rubio, H. A., Flores-Navarro, S., Escobedo-Melendez, G., Aranda-Romo, S., & Zepeda-Nuño, J. S. (2026). Oral Microbiome Dynamics in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Oral Mucositis. Microorganisms, 14(1), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010185