Oral GAD65-L. lactis Vaccine Halts Diabetes Progression in NOD Mice by Orchestrating Gut Microbiota–Metabolite Crosstalk and Fostering Intestinal Immunoregulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals, Experimental Design and Sampling

2.2. Intestinal Colonization Assay

2.3. Fecal Sample Collection

2.4. Detection of Target Biomolecules by ELISA

2.5. Flow Cytometry Assay

2.5.1. Splenic Lymphocyte Isolation

2.5.2. Intestinal Lamina Propria Lymphocyte Isolation

2.5.3. Flow Cytometry Staining

2.6. DNA Extraction and 16s rRNA Sequencing

2.7. Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis

2.7.1. Sample Preparation

2.7.2. LC-MS Analysis

2.8. Integrated Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Colonization of Recombinant Lactococcus lactis in the Gut

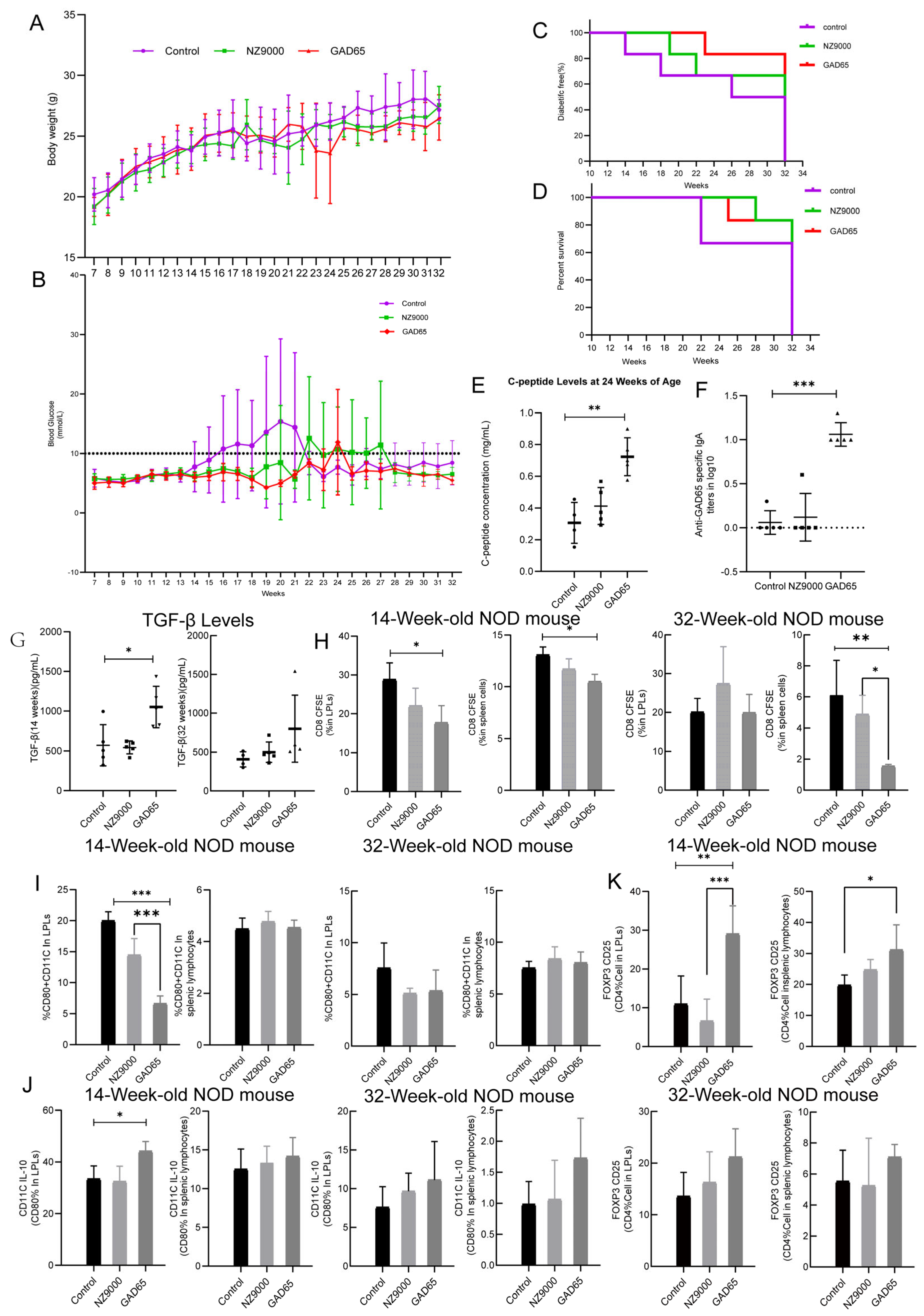

3.2. The Effect of GAD65-L. lactis on Suppressed Hyperglycemia and Diabetes

3.3. The Effect of GAD65-L. lactis on Humoral Immunity

3.4. The Effect of GAD65-L. lactis on Cellular Immunity

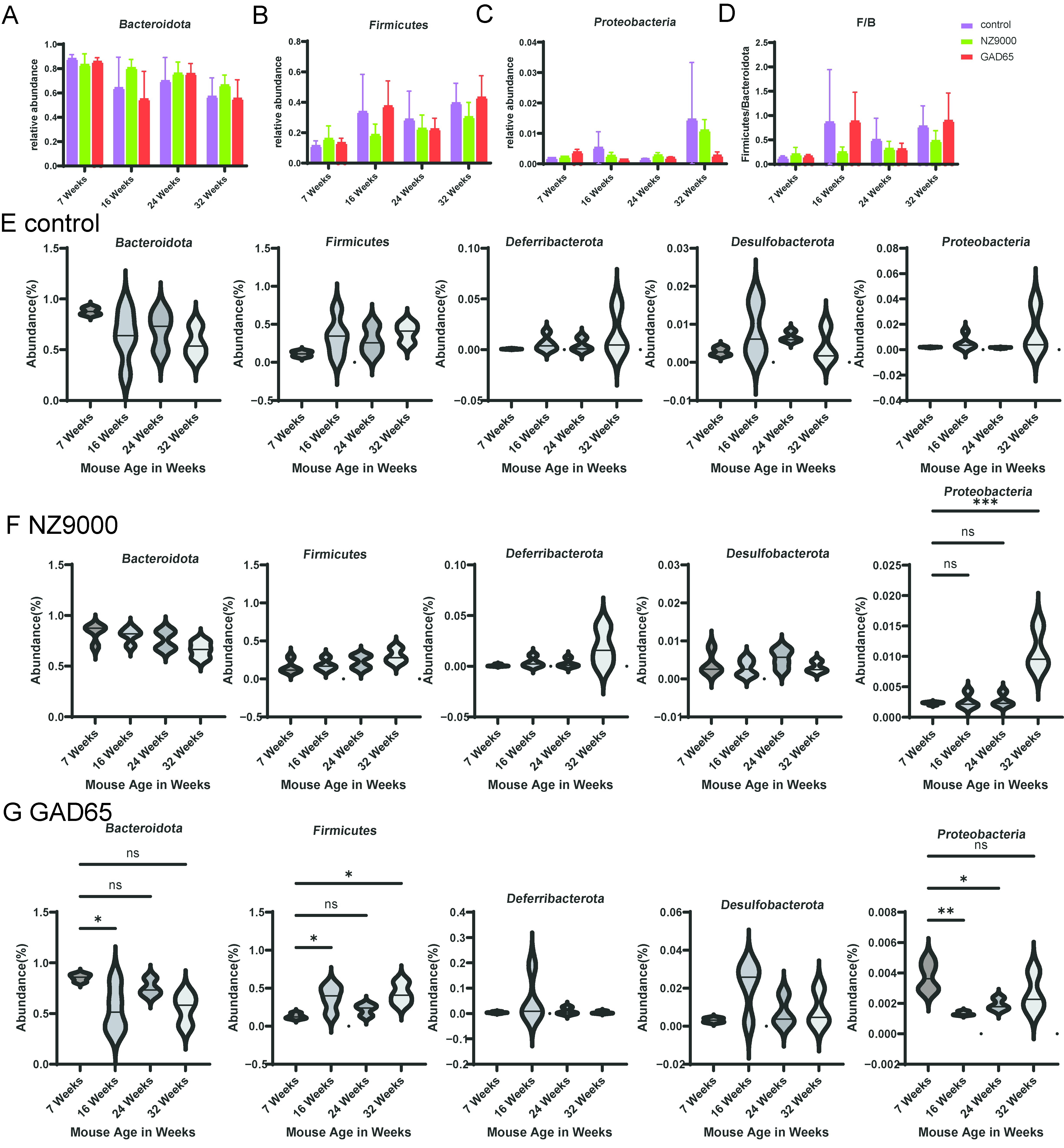

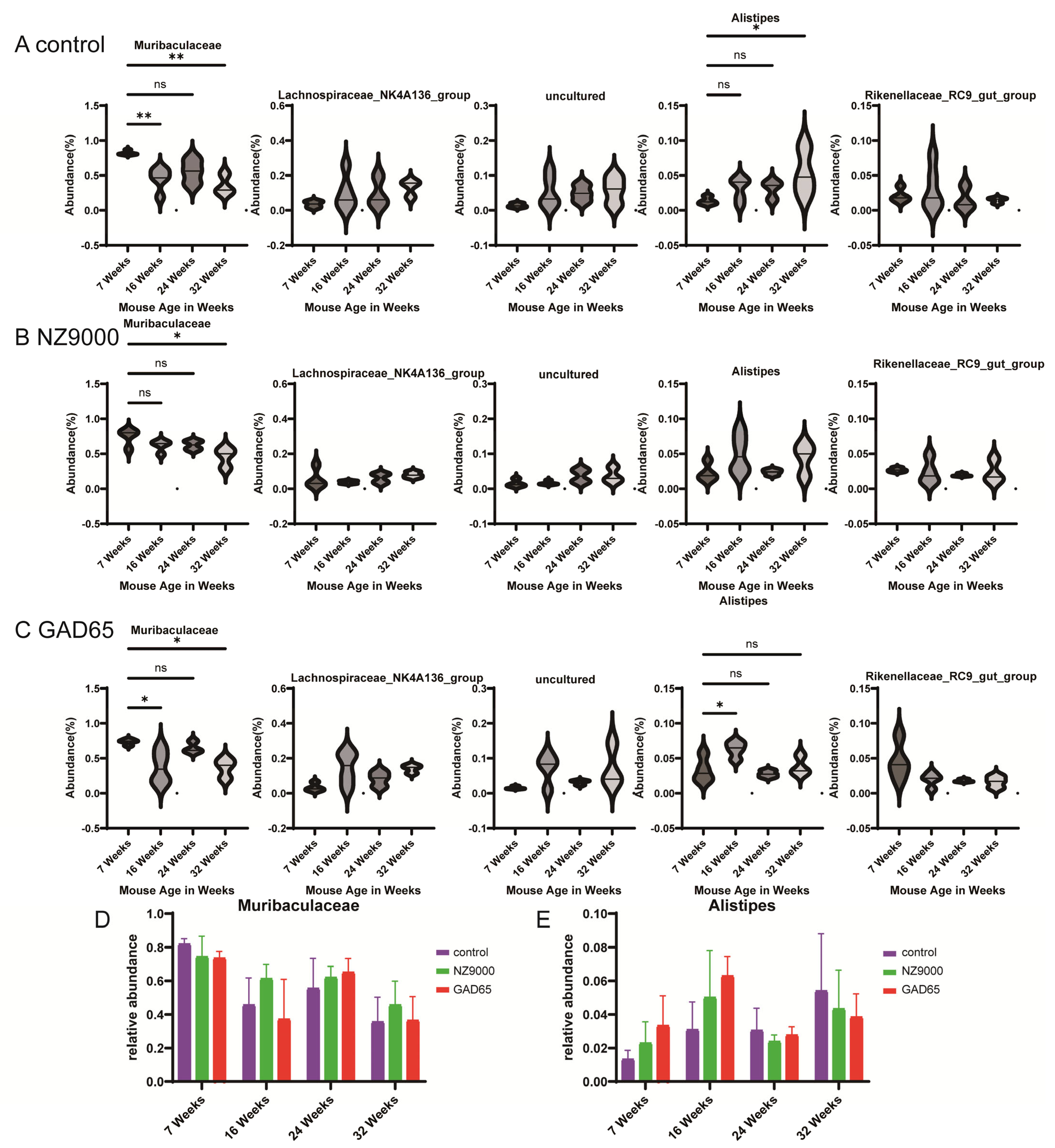

3.5. Alterations in Gut Microbial Diversity Following Oral Administration of L. lactis-Based Vaccine

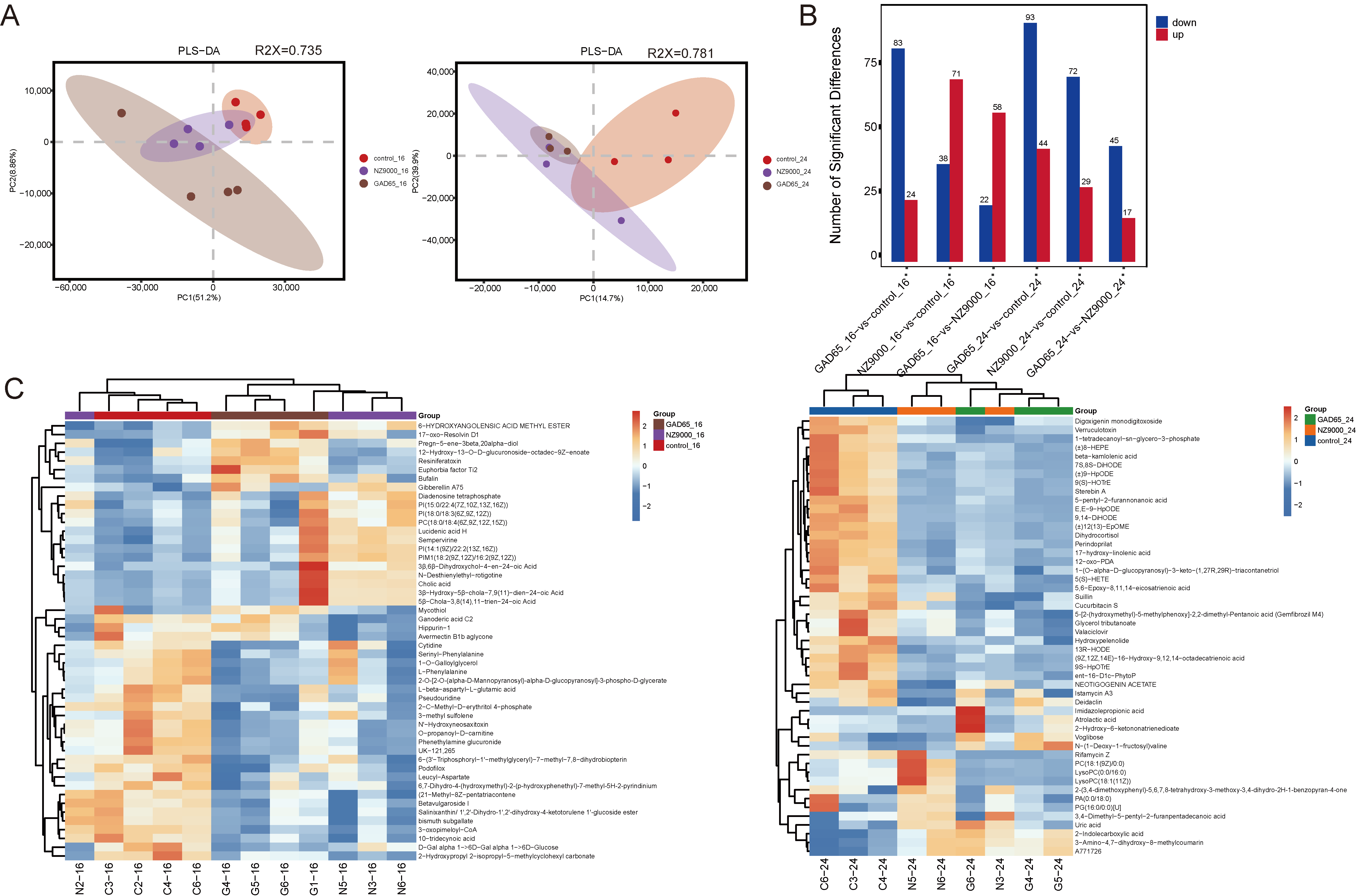

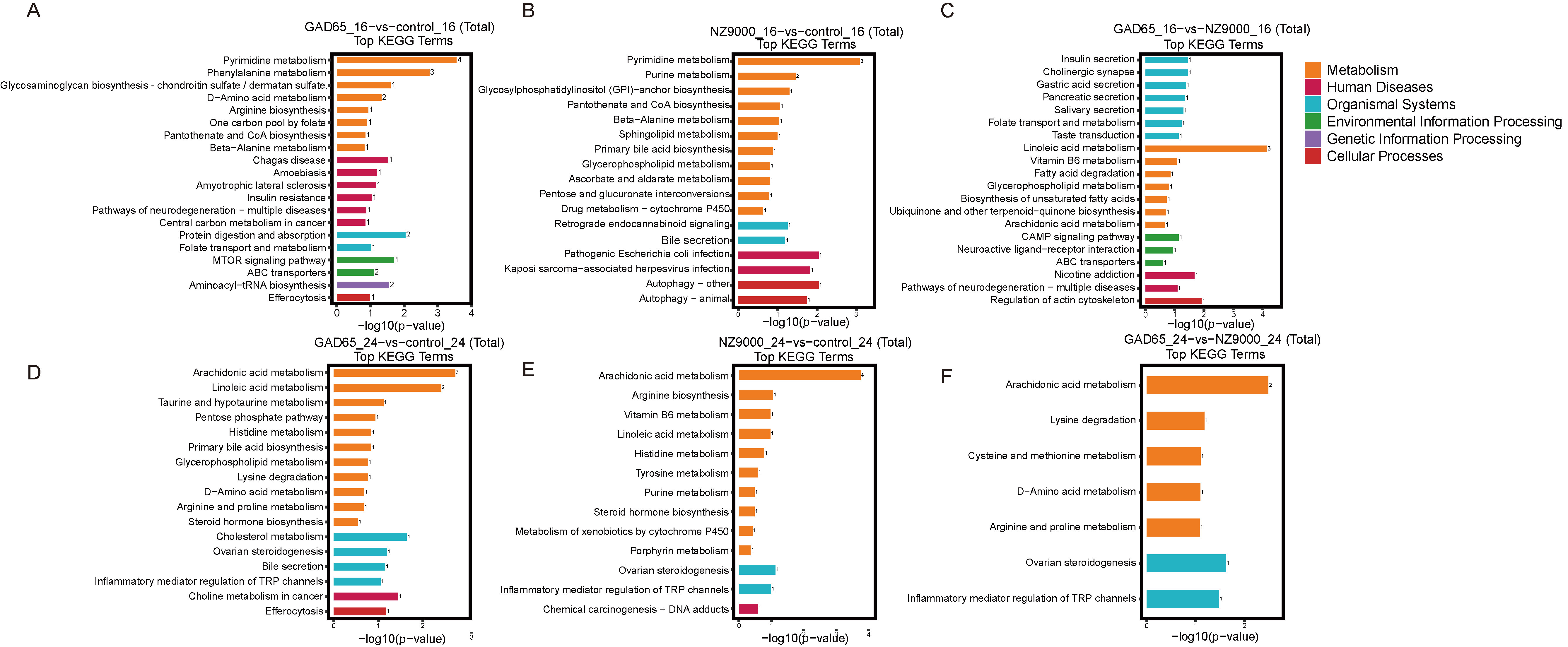

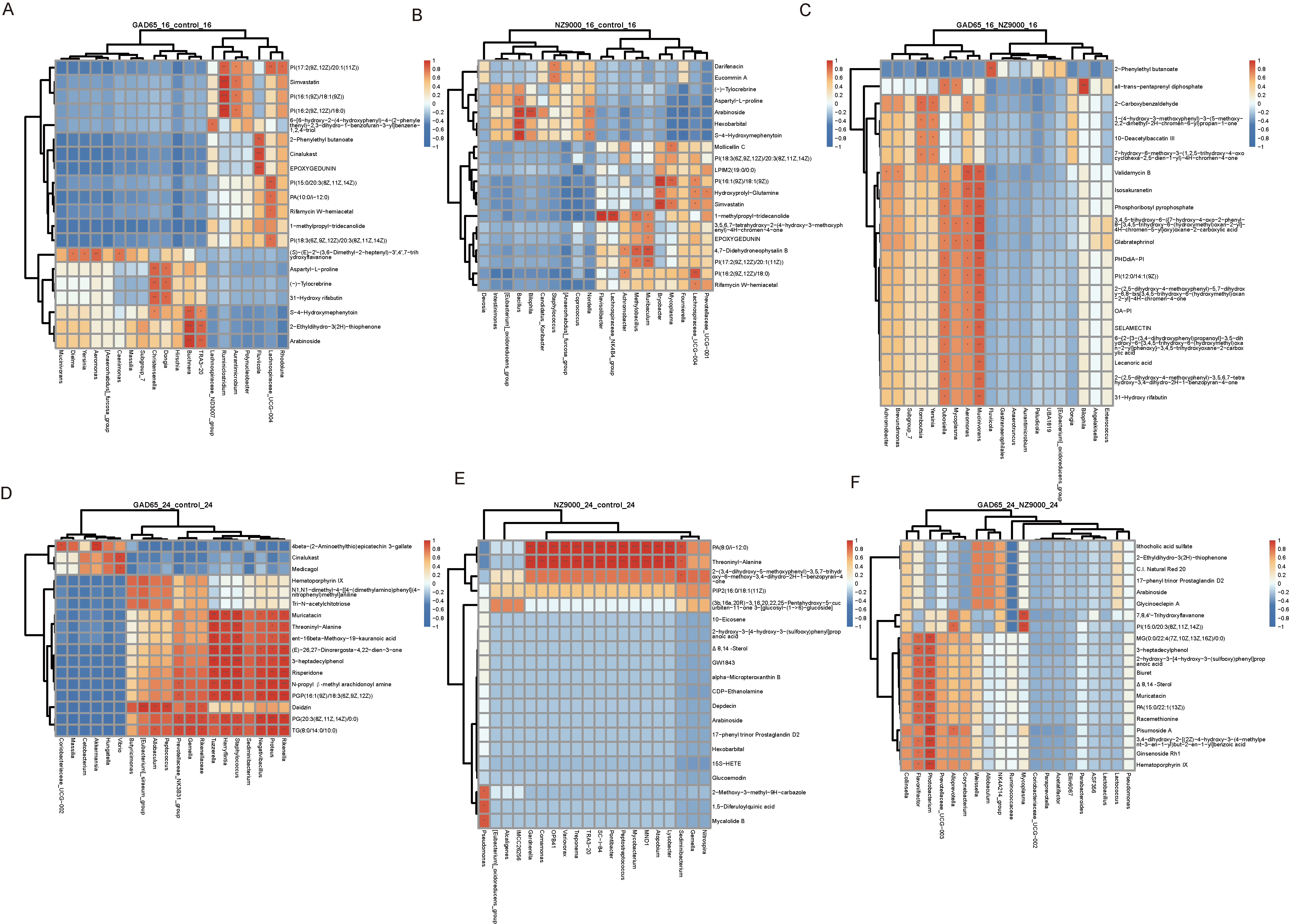

3.6. Screening of Differential Metabolites via Untargeted Metabolomics

3.7. Integrated Microbiome–Metabolome Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GAD65-L. lactis | recombinant Lactococcus lactis vaccine expressing GAD65 |

| T1D | type 1 diabetes |

| 16S rRNA sequencing | Integrated analyses of gut microbiota |

| DC (s) | dendritic cell (s) |

| Treg (s) | regulatory T cell (s) |

| SCFA (s) | short-chain fatty acid (s) |

References

- Ilonen, J.; Lempainen, J.; Veijola, R. The heterogeneous pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primavera, M.; Giannini, C.; Chiarelli, F. Prediction and Prevention of Type 1 Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluestone, J.A.; Buckner, J.H.; Herold, K.C. Immunotherapy: Building a bridge to a cure for type 1 diabetes. Science 2021, 373, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatanen, T.; Franzosa, E.A. The human gut microbiome in early-onset type 1 diabetes from the TEDDY study. Nature 2018, 562, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, J.; Hamet, P. Environmental and genetic contributions to diabetes. Metabolism 2019, 100, 153952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akil, A.A.; Yassin, E. Diagnosis and treatment of type 1 diabetes at the dawn of the personalized medicine era. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insel, R.; Dunne, J.L. JDRF’s vision and strategy for prevention of type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2016, 17, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, M.; Ma, C. Transcriptomic Analysis of Immune Tolerance Induction in NOD Mice Following Oral Vaccination with GAD65-Lactococcus lactis. Vaccines 2025, 13, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.R.; Dobson, R.C.J.; Morris, V.K.; Moggré, G.J. Fermentation of plant-based dairy alternatives by lactic acid bacteria. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022, 15, 1404–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Xie, X. Lactococcus lactis, a bacterium with probiotic functions and pathogenicity. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cui, Y. Mechanisms and improvement of acid resistance in lactic acid bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 2018, 200, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Su, A.C.Y.; Ding, X. Lactococcus lactis HkyuLL 10 suppresses colorectal tumourigenesis and restores gut microbiota through its generated alpha-mannosidase. Gut 2024, 73, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, G.; Yin, J. Lactobacillus delbrueckii might lower serum triglyceride levels via colonic microbiota modulation and SCFA-mediated fat metabolism in parenteral tissues of growing-finishing pigs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 982349. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Ding, J. Distinct signatures of gut microbiota and metabolites in different types of diabetes: A population-based cross-sectional study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 62, 102132. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.; Shi, Y. Machine learning approach reveals microbiome, metabolome, and lipidome profiles in type 1 diabetes. Adv. Res. 2024, 64, 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto, N.; Amiya, T. Commensal Lactobacillus Controls Immune Tolerance During Acute Liver Injury in Mice. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, L. Gut Microbiota Modulation on Intestinal Mucosal Adaptive Immunity. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 4735040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Xu, K. Impact of the Gut Microbiota on Intestinal Immunity Mediated by Tryptophan Metabolism. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhao, D. Implications of gut microbiota dysbiosis and metabolic changes in prion disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 135, 104704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.A.; Dhar, M. Modulation of diabetes with gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists in the nonobese mouse model of autoimmune diabetes. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, H.; Tondello, C. Inhibition of pyrimidine de novo synthesis fosters Treg cells and reduces diabetes development in models of type 1 diabetes. Mol. Metab. 2025, 100, 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knorr, S.; Lydolph, M.C. GAD65 autoantibodies and glucose tolerance in offspring born to women with and without type 1 diabetes (The EPICOM study). Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2022, 5, e00310. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, K.E.; Feduska, J.M. GABA and Combined GABA with GAD65-Alum Treatment Alters Th1 Cytokine Responses of PBMCs from Children with Recent-Onset Type 1 Diabetes. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Ludvigsson, J. GAD65: A prospective vaccine for treating Type 1 diabetes? Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2017, 17, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargahi, N.; Johnson, J. Immunomodulatory effects of probiotics: Can they be used to treat allergies and autoimmune diseases? Maturitas 2019, 119, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, S. Gut Firmicutes: Relationship with dietary fiber and role in host homeostasis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 12073–12088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.K.; Macia, L. Dietary fiber and SCFAs in the regulation of mucosal immunity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 151, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadh, M.J.; Allela, O.Q.B. The effects of microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids on T lymphocytes: From autoimmune diseases to cancer. Semin. Oncol. 2025, 52, 152398. [Google Scholar]

- Knip, M.; Siljander, H. The role of the intestinal microbiota in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knip, M.; Honkanen, J. Modulation of Type 1 Diabetes Risk by the Intestinal Microbiome. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2017, 17, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, W.J.; Yuan, J.J. Altered community compositions of Proteobacteria in adults with bronchiectasis. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2018, 13, 2173–2182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, P.J.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Kynurenine pathway metabolism and the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cheong, J.E.; Sun, L. Targeting the IDO1/TDO2-KYN-AhR Pathway for Cancer Immunotherapy—Challenges and Opportunities. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 39, 307–325. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, B. Exploration of the Muribaculaceae Family in the Gut Microbiota: Diversity, Metabolism, and Function. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.J.; Miller, R.A. Muribaculaceae Genomes Assembled from Metagenomes Suggest Genetic Drivers of Differential Response to Acarbose Treatment in Mice. mSphere 2021, 6, e00851-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Faas, M.M. Disease managing capacities and mechanisms of host effects of lactic acid bacteria. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1365–1393. [Google Scholar]

- Rezende, R.M.; Oliveira, R.P. Hsp65-producing Lactococcus lactis prevents experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice by inducing CD4+LAP+ regulatory T cells. J. Autoimmun. 2013, 40, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, C.M.; Chen, L. Gut microbes contribute to variation in solid organ transplant outcomes in mice. Microbiome 2018, 6, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 2012, 486, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcobal, A. A metabolomic view of how the human gut microbiota impacts the host metabolome using humanized and gnotobiotic mice. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1933–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakkola, J.; Bernasconi, C. Cytochrome P450 Induction and Xeno-Sensing Receptors Pregnane X Receptor, Constitutive Androstane Receptor, Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor and Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor α at The Crossroads of Toxicokinetics and Toxicodynamics. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 123, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, J.; Hao, J.; Guo, F. ABCB11 accumulated in immature tertiary lymphoid structures participates in xenobiotic metabolic process and predicts resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Transl. Oncol. 2023, 36, 101747. [Google Scholar]

- Dyall, S.C.; Balas, L. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and fatty acid-derived lipid mediators: Recent advances in the understanding of their biosynthesis, structures, and functions. Prog. Lipid Res. 2022, 86, 101165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innes, J.K.; Calder, P.C. Omega-6 fatty acids and inflammation. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2018, 132, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, K.J.; Saad, S. Metabolite-based dietary supplementation in human type 1 diabetes is associated with microbiota and immune modulation. Microbiome 2022, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, X. Action mechanism of hypoglycemic principle 9-(R)-HODE isolated from cortex lycii based on a metabolomics approach. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1011608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balla, T. Phosphoinositides: Tiny lipids with giant impact on cell regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 1019–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Groups | Dose | Number (NOD) |

|---|---|---|

| control | 100 µL PBS | 14 |

| GAD65 | 100 µL (1010 CFU/mL)/109 CFU/mouse | 14 |

| NZ9000 | 100 µL (1010 CFU/mL)/109 CFU/mouse | 14 |

| Metabolites | VIP | p-Value | log2FoldChange | Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAD65_16-vs.-control_16 | ||||

| L-Alloisoleucine | 14.6176 | 0.00695 | 1.14379 | Down |

| 3,4-Dihydro-2H-1-benzopyran-2-one | 12.7497 | 0.03683 | 1.23439 | Down |

| 2-Acetyl-1,5,6,7-tetrahydro-6-hydroxy-7-(hydroxymethyl)-4H-azepine-4-one | 8.03661 | 0.00385 | 0.94877 | Down |

| 2-C-Methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate | 6.65553 | 0.02902 | 1.22807 | Down |

| THTC | 6.15843 | 0.00932 | 1.39183 | Down |

| Dimetacrine tartrate | 5.68664 | 0.04027 | −1.2281 | Up |

| 6-Hydroxyangolensic Acid Methyl Ester | 2.2016 | 0.01755 | −0.7035 | Up |

| PC(DiMe(11,5)/MonoMe(11,3)) | 2.00352 | 0.0334 | −2.1317 | Up |

| Euphorbia factor Ti2 | 1.59097 | 0.03643 | −1.7298 | Up |

| 5-Hydroxypentanoic acid | 1.56521 | 0.01675 | −0.7437 | Up |

| NZ9000_16-vs.-control_16 | ||||

| Phenethylamine glucuronide | 4.48271 | 0.00479 | 1.89505 | Down |

| MG(0:0/16:1(9Z)/0:0) | 4.37551 | 0.02216 | 1.1632 | Down |

| Deoxyinosine | 4.10991 | 0.0031 | 1.26439 | Down |

| Telbivudine | 3.98936 | 0.03282 | 0.72069 | Down |

| Ganoderic acid C2 | 3.76156 | 0.00152 | 1.50722 | Down |

| (22R)-3alpha,7alpha,22-Trihydroxy-5beta-cholan-24-oic Acid | 57.3482 | 0.0488 | −1.5948 | Up |

| 3a,4b,12a-Trihydroxy-5b-cholanoic acid | 42.7362 | 0.03138 | −3.3462 | Up |

| 3α-Hydroxy-5β-chola-7,9(11)-dien-24-oic Acid | 25.5582 | 0.02002 | −2.4503 | Up |

| 5β-Chola-3,8(14),11-trien-24-oic Acid | 19.5152 | 0.02147 | −2.9188 | Up |

| PI(16:0/18:0) | 19.1612 | 0.04699 | −5.4381 | Up |

| GAD65_16-vs.-NZ9000_16 | ||||

| N-Acetyl-D-glucosamine | 8.9589 | 0.0309 | 0.65822 | Down |

| Desglymidodrine | 3.777 | 0.04995 | 0.53344 | Down |

| Acetylcholine | 3.43218 | 0.04823 | 0.42249 | Down |

| Acipimox (5-methylpyrazine-2-carboxylic acid) | 2.96428 | 0.00059 | 0.59656 | Down |

| 6-({3,5-dihydroxy-2-[hydroxy({2,3,4-trihydroxy-6-oxo-3-[3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]cyclohexa-1,4-dien-1-yl})methyl]oxan-4-yl}oxy)-3,4,5-trihydroxyoxane-2-carboxylic acid | 2.47561 | 0.02144 | 1.7766 | Down |

| xi-2,3-Dihydro-2-oxo-1H-indole-3-acetic acid | 9.93164 | 0.03713 | −0.8193 | Up |

| N1,N8-Diacetylspermidine | 9.02402 | 0.01602 | −1.0486 | Up |

| Hippurin-1 | 7.81028 | 0.04452 | −1.1046 | Up |

| M 344 | 5.64693 | 0.02168 | −1.4341 | Up |

| (9Z,12Z,14E)-16-Hydroxy-9,12,14-octadecatrienoic acid | 5.63666 | 0.04472 | −0.4385 | Up |

| GAD65_24-vs.-control_24 | ||||

| Taurocholic acid | 11.8384 | 0.03989 | 2.19745 | Down |

| (9Z,12Z,14E)-16-Hydroxy-9,12,14-octadecatrienoic acid | 8.46122 | 0.02868 | 1.77733 | Down |

| (±)12(13)-EpOME | 8.19732 | 0.00271 | 2.06938 | Down |

| E,E-9-HpODE | 6.12916 | 0.01663 | 2.53013 | Down |

| LysoPC(0:0/16:0) | 5.8749 | 0.02692 | 1.35126 | Down |

| 3-Amino-4,7-dihydroxy-8-methylcoumarin | 15.4917 | 0.04592 | -1.4871 | Up |

| 5-Aminopentanoic acid | 9.89937 | 0.01249 | -0.6199 | Up |

| Gaboxadol | 3.78973 | 0.004 | -0.4838 | Up |

| (3R)-3,4-Dihydroxy-3-(hydroxymethyl)butanenitrile 4-glucoside | 3.45038 | 0.03324 | -1.0679 | Up |

| 2-(2,4-dihydroxy-5-methoxyphenyl)-3-(3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)-5-hydroxy-8,8-dimethyl-4H,8H-pyrano[3,2-g]chromen-4-one | 2.12585 | 0.01757 | -1.4876 | Up |

| NZ9000-vs.-control_24 | ||||

| (9Z,12Z,14E)-16-Hydroxy-9,12,14-octadecatrienoic acid | 9.65671 | 0.0021 | 1.92272 | Down |

| (±)12(13)-EpOME | 9.1705 | 0.00855 | 2.11728 | Down |

| E,E-9-HpODE | 6.76751 | 0.01541 | 2.40964 | Down |

| Atrolactic acid | 6.7476 | 0.00804 | 0.96461 | Down |

| 17-hydroxy-linolenic acid | 6.48908 | 0.02538 | 1.87306 | Down |

| 7-Ketodeoxycholic acid | 9.82503 | 0.01961 | −0.6443 | Up |

| Uric acid | 3.27161 | 0.01999 | −2.4394 | Up |

| 17R-HDHA | 3.1493 | 0.0434 | −0.8553 | Up |

| Asymmetric dimethylarginine | 2.71701 | 0.04101 | −0.8598 | Up |

| Allopregnanalone sulfate | 2.60127 | 0.00377 | −2.6514 | Up |

| GAD65_24-vs.-NZ9000_24 | ||||

| 17-HOME(9Z) | 5.92395 | 0.02213 | 0.83256 | Down |

| (23S,24S)-17,23-Epoxy-24,29-dihydroxy-27-norlanost-8-ene-3,15-dione | 5.85579 | 0.048 | 0.74105 | Down |

| 2-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroxy-3-methoxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-1-benzopyran-4-one | 5.43801 | 0.01118 | 0.66076 | Down |

| Glycerol tributanoate | 5.34647 | 0.00572 | 1.67588 | Down |

| 3,4-Dimethyl-5-pentyl-2-furanpentadecanoic acid | 4.97022 | 0.04797 | 1.26745 | Down |

| 5-Aminopentanoic acid | 10.9735 | 0.01238 | −0.5518 | Up |

| Voglibose | 7.5184 | 0.02035 | −1.8284 | Up |

| 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 3-glycoside | 4.4632 | 0.01656 | −0.7329 | Up |

| 3,4,17-trihydroxy-9,10-seco-androsta-1,3,5(10)-triene-9-one | 3.9242 | 0.02041 | −1.0421 | Up |

| N1,N8-Diacetylspermidine | 2.43551 | 0.00131 | −0.5018 | Up |

| control_16-vs.-GAD65_16 | ||||

| L-Alloisoleucine | 14.6176 | 0.00695 | 1.14379 | Up |

| 3,4-Dihydro-2H-1-benzopyran-2-one | 12.7497 | 0.03683 | 1.23439 | Up |

| 2-Acetyl-1,5,6,7-tetrahydro-6-hydroxy-7-(hydroxymethyl)-4H-azepine-4-one | 8.03661 | 0.00385 | 0.94877 | Up |

| 2-C-Methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate | 6.65553 | 0.02902 | 1.22807 | Up |

| THTC | 6.15843 | 0.00932 | 1.39183 | Up |

| Dimetacrine tartrate | 5.68664 | 0.04027 | −1.2281 | Down |

| 6-HYDROXYANGOLENSIC ACID METHYL ESTER | 2.2016 | 0.01755 | −0.7035 | Down |

| PC(DiMe(11,5)/MonoMe(11,3)) | 2.00352 | 0.0334 | −2.1317 | Down |

| Euphorbia factor Ti2 | 1.59097 | 0.03643 | −1.7298 | Down |

| 5-Hydroxypentanoic acid | 1.56521 | 0.01675 | −0.7437 | Down |

| control_16-vs.-NZ9000_16 | ||||

| Phenethylamine glucuronide | 4.48271 | 0.00479 | 1.89505 | Up |

| MG(0:0/16:1(9Z)/0:0) | 4.37551 | 0.02216 | 1.1632 | Up |

| Deoxyinosine | 4.10991 | 0.0031 | 1.26439 | Up |

| Telbivudine | 3.98936 | 0.03282 | 0.72069 | Up |

| Ganoderic acid C2 | 3.76156 | 0.00152 | 1.50722 | Up |

| (22R)-3alpha,7alpha,22-Trihydroxy-5beta-cholan-24-oic Acid | 57.3482 | 0.0488 | −1.5948 | Down |

| 3a,4b,12a-Trihydroxy-5b-cholanoic acid | 42.7362 | 0.03138 | −3.3462 | Down |

| 3α-Hydroxy-5β-chola-7,9(11)-dien-24-oic Acid | 25.5582 | 0.02002 | −2.4503 | Down |

| 5β-Chola-3,8(14),11-trien-24-oic Acid | 19.5152 | 0.02147 | −2.9188 | Down |

| PI(16:0/18:0) | 19.1612 | 0.04699 | −5.4381 | Down |

| NZ9000_16-vs.-GAD65_16 | ||||

| N-Acetyl-D-glucosamine | 8.9589 | 0.0309 | 0.65822 | Up |

| Desglymidodrine | 3.777 | 0.04995 | 0.53344 | Up |

| Acetylcholine | 3.43218 | 0.04823 | 0.42249 | Up |

| Acipimox (5-methylpyrazine-2-carboxylic acid) | 2.96428 | 0.00059 | 0.59656 | Up |

| 6-({3,5-dihydroxy-2-[hydroxy({2,3,4-trihydroxy-6-oxo-3-[3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]cyclohexa-1,4-dien-1-yl})methyl]oxan-4-yl}oxy)-3,4,5-trihydroxyoxane-2-carboxylic acid | 2.47561 | 0.02144 | 1.7766 | Up |

| xi-2,3-Dihydro-2-oxo-1H-indole-3-acetic acid | 9.93164 | 0.03713 | −0.8193 | Down |

| N1,N8-Diacetylspermidine | 9.02402 | 0.01602 | −1.0486 | Down |

| Hippurin-1 | 7.81028 | 0.04452 | −1.1046 | Down |

| M 344 | 5.64693 | 0.02168 | −1.4341 | Down |

| (9Z,12Z,14E)-16-Hydroxy-9,12,14-octadecatrienoic acid | 5.63666 | 0.04472 | −0.4385 | Down |

| control_24-vs.-GAD65_24 | ||||

| Taurocholic acid | 11.8384 | 0.03989 | 2.19745 | Up |

| (9Z,12Z,14E)-16-Hydroxy-9,12,14-octadecatrienoic acid | 8.46122 | 0.02868 | 1.77733 | Up |

| (±)12(13)-EpOME | 8.19732 | 0.00271 | 2.06938 | Up |

| E,E-9-HpODE | 6.12916 | 0.01663 | 2.53013 | Up |

| LysoPC(0:0/16:0) | 5.8749 | 0.02692 | 1.35126 | Up |

| 3-Amino-4,7-dihydroxy-8-methylcoumarin | 15.4917 | 0.04592 | −1.4871 | Down |

| 5-Aminopentanoic acid | 9.89937 | 0.01249 | −0.6199 | Down |

| Gaboxadol | 3.78973 | 0.004 | −0.4838 | Down |

| (3R)-3,4-Dihydroxy-3-(hydroxymethyl)butanenitrile 4-glucoside | 3.45038 | 0.03324 | −1.0679 | Down |

| 2-(2,4-dihydroxy-5-methoxyphenyl)-3-(3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)-5-hydroxy-8,8-dimethyl-4H,8H-pyrano[3,2-g]chromen-4-one | 2.12585 | 0.01757 | −1.4876 | Down |

| control_24-vs.-NZ9000 | ||||

| (9Z,12Z,14E)-16-Hydroxy-9,12,14-octadecatrienoic acid | 9.65671 | 0.0021 | 1.92272 | Up |

| (±)12(13)-EpOME | 9.1705 | 0.00855 | 2.11728 | Up |

| E,E-9-HpODE | 6.76751 | 0.01541 | 2.40964 | Up |

| Atrolactic acid | 6.7476 | 0.00804 | 0.96461 | Up |

| 17-hydroxy-linolenic acid | 6.48908 | 0.02538 | 1.87306 | Up |

| 7-Ketodeoxycholic acid | 9.82503 | 0.01961 | −0.6443 | Down |

| Uric acid | 3.27161 | 0.01999 | −2.4394 | Down |

| 17R-HDHA | 3.1493 | 0.0434 | −0.8553 | Down |

| Asymmetric dimethylarginine | 2.71701 | 0.04101 | −0.8598 | Down |

| Allopregnanalone sulfate | 2.60127 | 0.00377 | −2.6514 | Down |

| NZ9000_24-vs.-GAD65_24 | ||||

| 17-HOME(9Z) | 5.92395 | 0.02213 | 0.83256 | Up |

| (23S,24S)-17,23-Epoxy-24,29-dihydroxy-27-norlanost-8-ene-3,15-dione | 5.85579 | 0.048 | 0.74105 | Up |

| 2-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroxy-3-methoxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-1-benzopyran-4-one | 5.43801 | 0.01118 | 0.66076 | Up |

| Glycerol tributanoate | 5.34647 | 0.00572 | 1.67588 | Up |

| 3,4-Dimethyl-5-pentyl-2-furanpentadecanoic acid | 4.97022 | 0.04797 | 1.26745 | Up |

| 5-Aminopentanoic acid | 10.9735 | 0.01238 | −0.5518 | Down |

| Voglibose | 7.5184 | 0.02035 | −1.8284 | Down |

| 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 3-glycoside | 4.4632 | 0.01656 | −0.7329 | Down |

| 3,4,17-trihydroxy-9,10-seco-androsta-1,3,5(10)-triene-9-one | 3.9242 | 0.02041 | −1.0421 | Down |

| N1,N8-Diacetylspermidine | 2.43551 | 0.00131 | −0.5018 | Down |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Ma, C.; Liu, T.; Qin, Q.; Shi, J.; Wu, M.; Sun, J.; Hu, Y. Oral GAD65-L. lactis Vaccine Halts Diabetes Progression in NOD Mice by Orchestrating Gut Microbiota–Metabolite Crosstalk and Fostering Intestinal Immunoregulation. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010176

Zhang S, Wang X, Ma C, Liu T, Qin Q, Shi J, Wu M, Sun J, Hu Y. Oral GAD65-L. lactis Vaccine Halts Diabetes Progression in NOD Mice by Orchestrating Gut Microbiota–Metabolite Crosstalk and Fostering Intestinal Immunoregulation. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010176

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shihan, Xinyi Wang, Chunli Ma, Tianyu Liu, Qingji Qin, Jiandong Shi, Meini Wu, Jing Sun, and Yunzhang Hu. 2026. "Oral GAD65-L. lactis Vaccine Halts Diabetes Progression in NOD Mice by Orchestrating Gut Microbiota–Metabolite Crosstalk and Fostering Intestinal Immunoregulation" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010176

APA StyleZhang, S., Wang, X., Ma, C., Liu, T., Qin, Q., Shi, J., Wu, M., Sun, J., & Hu, Y. (2026). Oral GAD65-L. lactis Vaccine Halts Diabetes Progression in NOD Mice by Orchestrating Gut Microbiota–Metabolite Crosstalk and Fostering Intestinal Immunoregulation. Microorganisms, 14(1), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010176