Assessment System and Optimization of the Thermal Extraction Methods for Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) from Microcystis

Abstract

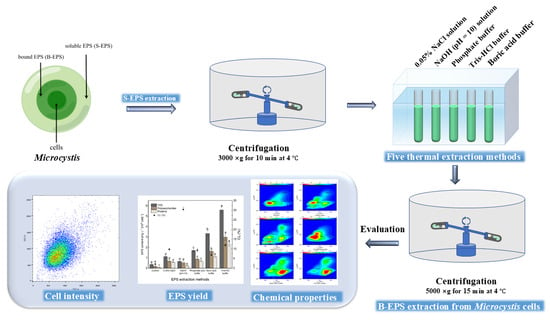

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Algae

2.2. Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) Extraction

2.3. Biochemical Composition Analysis

2.4. Flow Cytometry (FCM) Analysis for Cell Integrity Test

2.5. Microscopic Analysis and Quantification of Cell Disruption

2.6. Particle Size Distribution (PSD) Analysis

2.7. Three-Dimensional Excitation-Emission Matrix (3D-EEM) Fluorescence Spectroscopy

2.8. EPS Extraction Efficiency Evaluation

- (1)

- The treated Microcystis cells have two states of cells: intact cells and broken cells, where the proportion of broken cells is α.

- (2)

- Since Microcystis is prokaryotic and does not contain a nucleus, almost all nucleic acids are present in the cytoplasm.

- (3)

- Intracellular organic constituents (including polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, and related biomolecules) exhibit homogeneous spatial distribution patterns within individual algal cells. [TOCE], [TOCI], and CN are the extracellular total organic matter content, the intracellular total organic matter content, and the average content of nucleic acids in individual Microcystis cells, respectively. In summary, the measured TOC and nucleic acid expression can be obtained.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Evaluation System for EPS Extraction Methods

3.2. Biochemical Compositions of B-EPS Extracted by Different Methods and Conditions

3.3. Cell Integrity Analysis

3.4. Chemical Characteristics of EPS Extracted from Microcystis

3.5. The Particle Size Distribution (PSD) and Morphology of Microcystis

3.6. Extraction Efficiency of Different Methods and Conditions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. EPS Extraction

References

- Babakhani, P.; Mahdavi, M.A.; Gheshlaghi, R.; Karimian, A. The shift in carbon source induces pH increase and autoflocculation in microalgal suspensions facilitating multi-approach biomass harvesting. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 27049–27060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.K.; Yang, R.; Zhang, S.R.; Fang, F.; Huo, Y.C.; Yan, P.; Chen, Y.P.; Guo, J.S. Extracellular polymeric substances enhanced photosynthesis over respiration in Microcystis aeruginosa. Harmful Algae 2025, 145, 102843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Yang, F.; Pang, Q.; Peng, F.; Xu, B.; Wang, L.; Xie, L.; Zhang, W.; Tian, L.; Hou, J.; et al. Fluvial dissolved organic matter quality modulates microbial nitrate transformation: Enhanced denitrification under low Carbon-to-Nitrate ratio. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 23456–23465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.L.; Zhong, C.J.; Qing, T.; Du, Z.Y.; Li, C.C.; Fei, J.J.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M. Effects of extracellular polymeric substances on silver nanoparticle bioaccumulation and toxicity to Triticum aestivum L. Chemosphere 2021, 280, 130863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, K.; Kashian, D.R. Extracellular polymeric substances in green alga facilitate microplastic deposition. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, M.S.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhang, M.M.; Zhou, H.X.; Zhang, Y.X.; Sheng, Q.; Zhao, J.H.; Xu, Q.Y.; Zhang, R.F. Effects of intracellular polysaccharides and proteins of Auxenochlorella pyrenoidosa on water quality, floc formation, and microbial composition in a biofloc system. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.H.; Lin, J.H.; Zhan, W.L.; Li, J.J.; Dong, X.X.; Zhang, T.T.; Yang, Z.X.; Luo, Z.X.; Guo, P.Y. Extracellular polymers substances towards the toxicity effect of Microcystis flos-aquae under subjected to nanoplastic stress. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 372, 125996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Tiwari, M.; Poluri, K.M. A biorefinery approach integrating lipid and EPS augmentation along with Cr (III) mitigation by Chlorella minutissima. Cells 2024, 13, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P.; Bandyopadhyay, T.K.; Gopikrishna, K.; Tiwari, O.N.; Bhunia, B.; Muthuraj, M. Algal carbohydrates: Sources, biosynthetic pathway, production, and applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 413, 131489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, M.; Li, M.; Duan, P.F.; Qu, Z.; Wu, H.M. Insights into the relationship between colony formation and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) composition of the cyanobacterium Microcystis spp. Harmful Algae 2019, 83, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, P.H.; Jahn, A.; Palmgren, R. Conceptual model for production and composition of exopolymers in biofilms. Water Sci. Technol. 1997, 36, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.P.; Tan, X.; Zhang, D.F.; Parajuli, K. Development of thermal treatment for the extraction of extracellular polymeric substances from Microcystis: Evaluating extraction efficiency and cell integrity. Algal Res. 2020, 48, 101879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.X.; He, Q.; Ma, J.; Ma, C.X.; Xu, Y.H.; Song, J.H.; Sun, L.L.; Wu, Z.S.; Huangfu, X.L. Quantitative assessment of extraction methods for bound extracellular polymeric substances (B-EPSs) produced by Microcystis sp. and Scenedesmus sp. Algal Res. 2021, 56, 102289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.Z.; Qin, B.Q.; Zhang, Y.L.; Zhu, G.W.; Gao, G.; Huang, Q.; Yao, X. Extraction and characterization of bound extracellular polymeric substances from cultured pure cyanobacterium (Microcystis wesenbergii). J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 26, 1725–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.C.; Yu, G.H.; Jiang, H.L. Investigation on extracellular polymeric substances from mucilaginous cyanobacterial blooms in eutrophic freshwater lakes. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, Y.T.; Chan, D.J.C. A methodological review on the characterization of microalgal biofilm and its extracellular polymeric substances. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 3490–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klock, J.H.; Wieland, A.; Seifert, R.; Michaelis, W. Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) from cyanobacterial mats: Characterisation and isolation method optimisation. Mar. Biol. 2007, 152, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eenennaam, J.S.; Wei, Y.Z.; Grolle, K.C.F.; Foekema, E.M.; Murk, A.J. Oil spill dispersants induce formation of marine snow by phytoplankton-associated bacteria. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 104, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.M.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Sui, Z.H. Screening of ApDOT1.9 interacting proteins and the potential function of interactor ApSNARE in the rapid growth regulation of Alexandrium pacificum. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 209, 117080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braspaiboon, S.; Osiriphun, S.; Surawang, S.; Jirarattanarangsri, W.; Kanha, N.; Laokuldilok, T. Ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction of proteins in several algae and their nutritional characteristics. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 6143–6154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhu, W.; Gao, L. Analysis of cell concentration, volume concentration, and colony size of Microcystis via laser particle analyzer. Environ. Manag. 2014, 53, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felz, S.; Vermeulen, P.; van Loosdrecht, M.; Lin, Y. Chemical characterization methods for the analysis of structural extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). Water Res. 2019, 157, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Li, D.; Rong, S.; Su, L.; Zhou, W.; Wang, P.; Wang, C.; Li, S.; Acharya, K. Characterization of extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) fractions produced by Microcystis aeruginosa under the stress of linoleic acid sustained-release microspheres. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 21091–21102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzawa, T.; Watanabe, A.; Shintani, T.; Gomi, K.; Yaoi, K. Enzymatic degradation of xyloglucans by Aspergillus species: A comparative view of this genus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 2701–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Nguyen, B.T.; Lai, Y.S.; Zhou, C.; Xia, S.; Rittmann, B.E. Using flow cytometry to evaluate thermal extraction of EPS from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Algal Res. 2016, 20, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.D.; Wang, M.; Liu, S.H.; Xu, D.L.; Fei, X.W. Effects of the skp1 gene of the SCF complex on lipid metabolism and response to abiotic stress in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1527439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, G.P.; Yu, H.Q.; Li, X.Y. Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) of microbial aggregates in biological wastewater treatment systems: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.C.; Cai, H.Y.; Yu, G.H.; Jiang, H.L. Insights into extracellular polymeric substances of cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa using fractionation procedure and parallel factor analysis. Water Res. 2013, 47, 2005–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.F.; Liu, S.X.; Liu, N.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Q.Z.; Ge, F. Accelerated productions and physicochemical characterizations of different extracellular polymeric substances from Chlorella vulgaris with nano-ZnO. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, X.C.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhao, B.; An, Q. Unraveling the two-sided effect of nitrate on aerobic granulation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 479, 147430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzhiumparambil, U.; Labeeuw, L.; Commault, A.; Vu, H.P.; Nguyen, L.N.; Ralph, P.J.; Nghiem, L.D. Effects of harvesting on morphological and biochemical characteristics of microalgal biomass harvested by polyacrylamide addition, pH-induced flocculation, and centrifugation. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 359, 127433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Z.P.; Tan, X.; Guo, J.J.; Kahehu, C.W.; Yang, H.P.; Zheng, X.Y.; Zhu, F. Effects of biological and physical properties of microalgae on disruption induced by a low-frequency ultrasound. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 2937–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Xie, Y.C.; Li, X.Q.; Liu, W.Z.; Han, J.L.; Zheng, C.Y.; Zheng, Q.; Zhao, X.Z.; Wang, A.J. Why the disinfection efficiency of ultraviolet radiation may become unsatisfactory at low suspended solid concentrations: The mechanism of extracellular polymeric substances secretion induced by different particles. Water Res. 2025, 274, 123122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Patidar, S.K. Microalgae harvesting techniques: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 217, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Oshita, K.; Takaoka, M. Flocculation properties of eight microalgae induced by aluminum chloride, chitosan, amphoteric polyacrylamide, and alkaline: Life-cycle assessment for screening species and harvesting methods. Algal Res. 2021, 54, 102226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.C.; Lv, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, P.F.; Jiang, H.L. Electrolyte cations binding with extracellular polymeric substances enhanced Microcystis aggregation: Implication for Microcystis bloom formation in eutrophic freshwater lakes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 9034–9043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extraction Methods | Extraction Conditions | Polysaccharides (mg L−1) | Proteins (mg L−1) | TOC (mg L−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphate buffer | 55 °C, 30 min | 0.73 ± 0.08 | 0.68 ± 0.08 | 1.55 ± 0.10 |

| Boric acid buffer | 55 °C, 30 min | 1.33 ± 0.11 | 0.89 ± 0.07 | 2.81 ± 0.15 |

| Tris-HCl buffer | 60 °C, 30 min | 2.98 ± 0.08 | 2.28 ± 0.18 | 5.6 ± 0.064 |

| FSC | FITC | CL (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events in Gate (%) | Signal Intensity | Events in Gate (%) | Fluorescent Signal | ||||

| P1 | P2 | Mean ± SD (105) | Q1 | Q2 | Mean ± SD (105) | ||

| Control | 5.4 | 94.6 | 1.5 ± 0.25 | 2.6 | 97.4 | 0.06 ± 0.001 | 2.1 |

| Phosphate buffer | 6.6 | 93.4 | 1.3 ± 0.02 | 3.0 | 97.0 | 0.05 ± 0.001 | 9.3 |

| Boric acid buffer | 8.1 | 91.9 | 1.2 ± 0.02 | 9.8 | 90.2 | 0.05 ± 0.001 | 6.9 |

| Tris-HCl buffer | 5.7 | 94.3 | 1.1 ± 0.08 | 1.2 | 98.8 | 0.04 ± 0.001 | 12.0 |

| 0.05% NaCl | 30.5 | 69.5 | 0.7 ± 0.01 | 1.4 | 98.6 | 0.04 ± 0.005 | 9.8 |

| NaOH (pH = 10) | 49.8 | 50.2 | 0.7 ± 0.04 | 16.5 | 83.5 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 30.4 |

| Methods | Peak A | Peak B | Peak C | Peak D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ex/Em | Intensity | Ex/Em | Intensity | Ex/Em | Intensity | Ex/Em | Intensity | |

| Control | 280/335 | 66.38 | 250/450 | 22.32 | 355/455 | 14.45 | / | / |

| 0.05% NaCl | 280/335 | 206.50 | 225/335 | 144.05 | 355/455 | 53.67 | 230/330 | 138.62 |

| NaOH (pH = 10) | 280/340 | 45.07 | 225/340 | 48.15 | 360/455 | 30.46 | 230/330 | 81.09 |

| Phosphate buffer | 280/335 | 510.30 | 225/330 | 148.29 | / | / | / | / |

| Boric acid buffer | 280/335 | 348.04 | 250/450 | 625.15 | 355/455 | 296.75 | / | / |

| Tris-HCl buffer | 280/335 | 197.12 | 250/450 | 505.66 | 355/455 | 283.26 | / | / |

| Methods | Conditions | Calculated Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | φ | ε | ||

| Control | – | 0.02 ± 0.01 a | 0.04 ± 0.01 a | 2.56 ± 0.22 b |

| 0.05% NaCl | 60 °C, 30 min | 0.098 ± 0.01 a | 0.17 ± 0.02 a | 2.13 ± 0.19 b |

| NaOH (pH = 10) | 45 °C, 4 h | 0.30 ± 0.02 b | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | 0.14 ± 0.01 a |

| Phosphate buffer | 55 °C, 30 min | 0.093 ± 0.01 a | 0.29 ± 0.02 a | 3.90 ± 0.28 b |

| Boric acid buffer | 55 °C, 30 min | 0.069 ± 0.01 a | 0.62 ± 0.02 b | 11.06 ± 1.13 c |

| Tris-HCl buffer | 60 °C, 30 min | 0.12 ± 0.02 a | 0.94 ± 0.04 b | 9.7 ± 0.81 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cui, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, P.; Cui, J.; Song, S.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, D. Assessment System and Optimization of the Thermal Extraction Methods for Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) from Microcystis. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010116

Cui Y, Zhang S, Zhao P, Cui J, Song S, Qu Y, Zhang H, Ma D. Assessment System and Optimization of the Thermal Extraction Methods for Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) from Microcystis. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010116

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Yafei, Sheng Zhang, Pengbo Zhao, Jingyuan Cui, Shuwei Song, Yao Qu, Haiping Zhang, and Dong Ma. 2026. "Assessment System and Optimization of the Thermal Extraction Methods for Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) from Microcystis" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010116

APA StyleCui, Y., Zhang, S., Zhao, P., Cui, J., Song, S., Qu, Y., Zhang, H., & Ma, D. (2026). Assessment System and Optimization of the Thermal Extraction Methods for Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) from Microcystis. Microorganisms, 14(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010116