Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis (Lymphangitic Type) in an Immunocompetent Patient: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

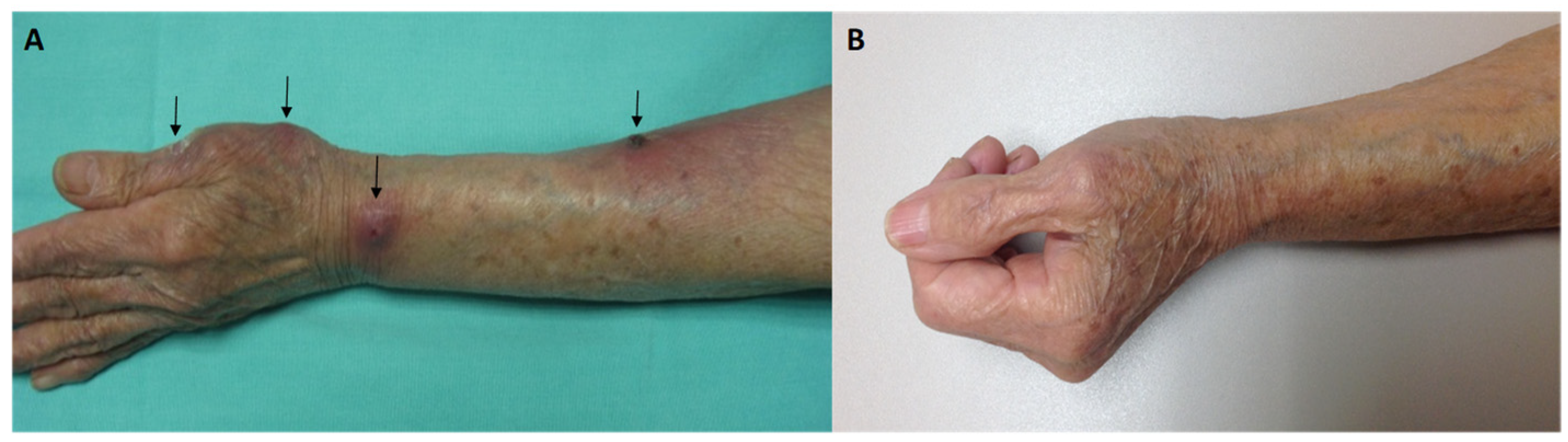

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilson, J.W. Nocardiosis: Updates and clinical overview. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2012, 87, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhong, B.; Song, Z.; Yang, X. Disseminated nocardiosis caused by Nocardia elegans: A case report and review of the literature. Infection 2018, 46, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T.S.; Scott, J.X.; Viswanathan, S. Cervicofacial nocardiosis in an immunocompetent child. Acta Paediatr. 2005, 94, 1342–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercibengoa, M.; Vicente, D.; Arranz, L.; Ugarte, A.; Marimon, J. Primary cutaneous Nocardia brasiliensis in a Spanish child. Clin. Lab. 2018, 64, 1769–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatahi-Bafghi, M. Nocardiosis from 1888 to 2017. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 114, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agterof, M.; van der Bruggen, T.; Tersmette, M.; ter Borg, E.; van den Bosch, J.; Biesma, D. Nocardiosis: A case series and a mini review of clinical and microbiological features. Neth. J. Med. 2007, 65, 199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Sonneville, R.; Ruimy, R.; Benzonana, N. An update on bacterial brain abscess in immunocompetent patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzaferri, F.; Cordioli, M.; Segato, E. Nocardia infection over 5 years (2011–2015) in an Italian tertiary care hospital. New Microbiol. 2018, 41, 136–140. [Google Scholar]

- Dodiuk-Gad, R.; Cohen, E.; Ziv, M.; Goldstein, L.H.; Chazan, B.; Shafer, J.; Sprecher, H.; Elias, M.; Keness, Y.; Rozenman, D. Cutaneous nocardiosis: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Int. J. Dermatol. 2010, 49, 1380–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Bao, F.; Zhang, F. Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2024, 160, 1237–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosioni, J.; Lew, D.; Garbino, J. Nocardiosis: Updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection. 2010, 38, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmila, P.; Manjyot, M.G.; Avani, A.; Kaleem, J. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis with craniocerebral extension: A case report. Dermatol. Online J. 2010, 15, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, H.; Saotome, A.; Usami, N.; Urushibata, O.; Mukai, H. Lymphocutaneous type of nocardiosis caused by Nocardia brasiliensis: A case report and review of primary cutaneous nocardiosis caused by N. brasiliensis reported in Japan. J. Dermatol. 2008, 35, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iotti, L.R.; de Frutos, M.; Lorenzo-Vidal, B.; Eiros, J.M. Nocardiosis diseminada [Disseminated nocardiosis]. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 2024, 37, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besteiro, B.; Coutinho, D.; Fragoso, J.; Figueiredo, C.; Nunes, S.; Azevedo, C.; Teixeira, T.; Selaru, A.; Abreu, G.; Malheiro, L. Nocardiosis: A single-center experience and literature review. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 27, 102806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggal, S.D.; Chugh, T.D. Nocardiosis: A Neglected Disease. Med. Princ. Pract. 2020, 29, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Elliot, B.A.; Brown, J.M.; Conville, P.S.; Wallace, R.J., Jr. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, M.; Arenas, R.; Vasquez del Mercado, E.; Fernandez, R.; Torres, E.; Zacarias, R. Efficacy of imipenem therapy for Nocardia actinomycetomas refractory to sulfonamides. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010, 62, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujol-Montcus, J.A.; Pastor-Jane, L.; Simo-Esque, M.; Diaz, M.L.; Turegano-Fuentes, P. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis caused by Nocardia transvalensis in an immunocompetent patient. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 64, P2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-E-Silva, M.; Lopes, R.S.; Trope, B.M. Cutaneous nocardiosis: A great imitator. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 38, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songo, A.; Jacquier, H.; Danjean, M.; Compain, F.; Dorchène, D.; Edoo, Z.; Woerther, P.L.; Arthur, M.; Lebeaux, D. Analysis of two Nocardia brasiliensis class A β-lactamases (BRA-1 and BRS-1) and related resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 42, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, J.; Mirelis, B.; Aragón, L.M.; Gutiérrez, N.; Sánchez, F.; Español, M.; Esparcia, O.; Gurguí, M.; Domingo, P.; Coll, P. Clinical and microbiological features of nocardiosis 1997–2003. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 56, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xu, X.; Wu, M.; Zhu, J.; Cen, P.; Ding, J.; Wu, S.; Jin, J. Lymphocutaneous nocardiosis caused by Nocardia brasiliensis in an immunocompetent patient: A case report. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060519897690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Xu, X.; Ran, Y. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis caused by Nocardia brasiliensis following a wasp sting. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2017, 42, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ortega, J.I.; Franco-Gonzalez, S.; Ramirez Cibrian, A.G. An immune-based therapeutical approach in an elderly patient with fixed cutaneous sporotrichosis. Cureus 2024, 16, e53192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smego, R.A., Jr.; Castiglia, M.; Asperilla, M.O. Lymphocutaneous syndrome. A review of non-sporothrix causes. Medicine 1999, 78, 38–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Zhang, X.; Du, P.; Li, G.; Li, L.; Li, Z. Susceptibility profiles of Nocardia spp. to antimicrobial and antituberculotic agents detected by a microplate Alamar Blue assay. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, R.M.; Bell, M.E.; Lasker, B.; Headd, B.; Shieh, W.J.; McQuiston, J.R. Updated review on Nocardia species: 2006–2021. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2022, 35, e0002721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conville, P.S.; Brown-Elliott, B.A.; Smith, T.; Zelazny, A.M. The Complexities of Nocardia Taxonomy and Identification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 56, e01419-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, S.Y.; Deng, J.; Zhuang, K.W.; Tang, Y.; Wu, N.; Zhang, W.L.; Liao, Q.F.; Xiao, Y.L.; Kang, M. Application of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for identification of Nocardia species. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalit, I.; Lebeaux, D.; Tishler, O.; Goldberg, E.; Bishara, J.; Yahav, D.; Coussement, J. How do I manage nocardiosis? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifaz, A.; García-Sotelo, R.S.; Lumbán-Ramirez, F.; Vázquez-González, D.; Inclán-Reyes, J.I.; Sierra-Garduño, M.E.; Araiza, J.; Chandler, D. Update on actinomycetoma treatment: Linezolid in the treatment of actinomycetomas due to Nocardia spp. and Actinomadura madurae resistant to conventional treatments. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2025, 23, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, Z.; Xia, X. Acute primary cutaneous nocardiosis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2024, 110, 848–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Sun, Q.; Yan, J.; Liao, X.; Long, S.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Shi, G.; Zhao, Y.; et al. The species distribution and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Nocardia species in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attias, N.H.; Schlaeffer-Yosef, T.; Zahavi, I.; Hasson, N.; Ari, Y.B.; Darawsha, B.; Levitan, I.; Goldberg, E.; Landes, M.; Litchevsky, V.; et al. Shorter vs. standard-duration antibiotic therapy for nocardiosis: A multi-center retrospective cohort study. Infection 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.A.; Young, R.; Sridhar, J.; Nocardia Study Group. Nocardia choroidal abscess: Risk factors, treatment strategies, and visual outcomes. Retina 2015, 35, 2137–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, C.T.; Imkamp, F.; Marques Maggio, E.; Brugger, S.D. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis of the head and neck in an immunocompetent patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e241217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Su, F.; Hong, X.; Chen, M.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, D.; Ge, Y. Successful treatment with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid: Cutaneous nocardiosis caused by Nocardia brasiliensis. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2023, 34, 2229467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, S.; Pai, K.; Sharma, S. Cutaneous nocardiosis: An underdiagnosed pathogenic infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr2014208713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aguilar-Molina, H.; Toussaint-Caire, S.; Arenas, R.; Xicohtencatl-Cortes, J.; Martínez-Chavarría, L.C.; Hernández-Castro, R.; Rodriguez-Cerdeira, C. Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis (Lymphangitic Type) in an Immunocompetent Patient: A Case Report. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13051022

Aguilar-Molina H, Toussaint-Caire S, Arenas R, Xicohtencatl-Cortes J, Martínez-Chavarría LC, Hernández-Castro R, Rodriguez-Cerdeira C. Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis (Lymphangitic Type) in an Immunocompetent Patient: A Case Report. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(5):1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13051022

Chicago/Turabian StyleAguilar-Molina, Hilayali, Sonia Toussaint-Caire, Roberto Arenas, Juan Xicohtencatl-Cortes, Luary C. Martínez-Chavarría, Rigoberto Hernández-Castro, and Carmen Rodriguez-Cerdeira. 2025. "Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis (Lymphangitic Type) in an Immunocompetent Patient: A Case Report" Microorganisms 13, no. 5: 1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13051022

APA StyleAguilar-Molina, H., Toussaint-Caire, S., Arenas, R., Xicohtencatl-Cortes, J., Martínez-Chavarría, L. C., Hernández-Castro, R., & Rodriguez-Cerdeira, C. (2025). Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis (Lymphangitic Type) in an Immunocompetent Patient: A Case Report. Microorganisms, 13(5), 1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13051022