Disruption of the Nitric Oxide Reductase Operon via norD Deletion Does Not Affect Brucella abortus 2308W Virulence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Plasmids

2.2. Bacterial Growth and Survival Conditions

2.3. DNA Manipulations

2.4. Mutagenesis

2.5. Infection of Activated and Non-Activated RAW264.7 Macrophages

2.6. Virulence Assay in Mice

2.7. Statistical Analysis

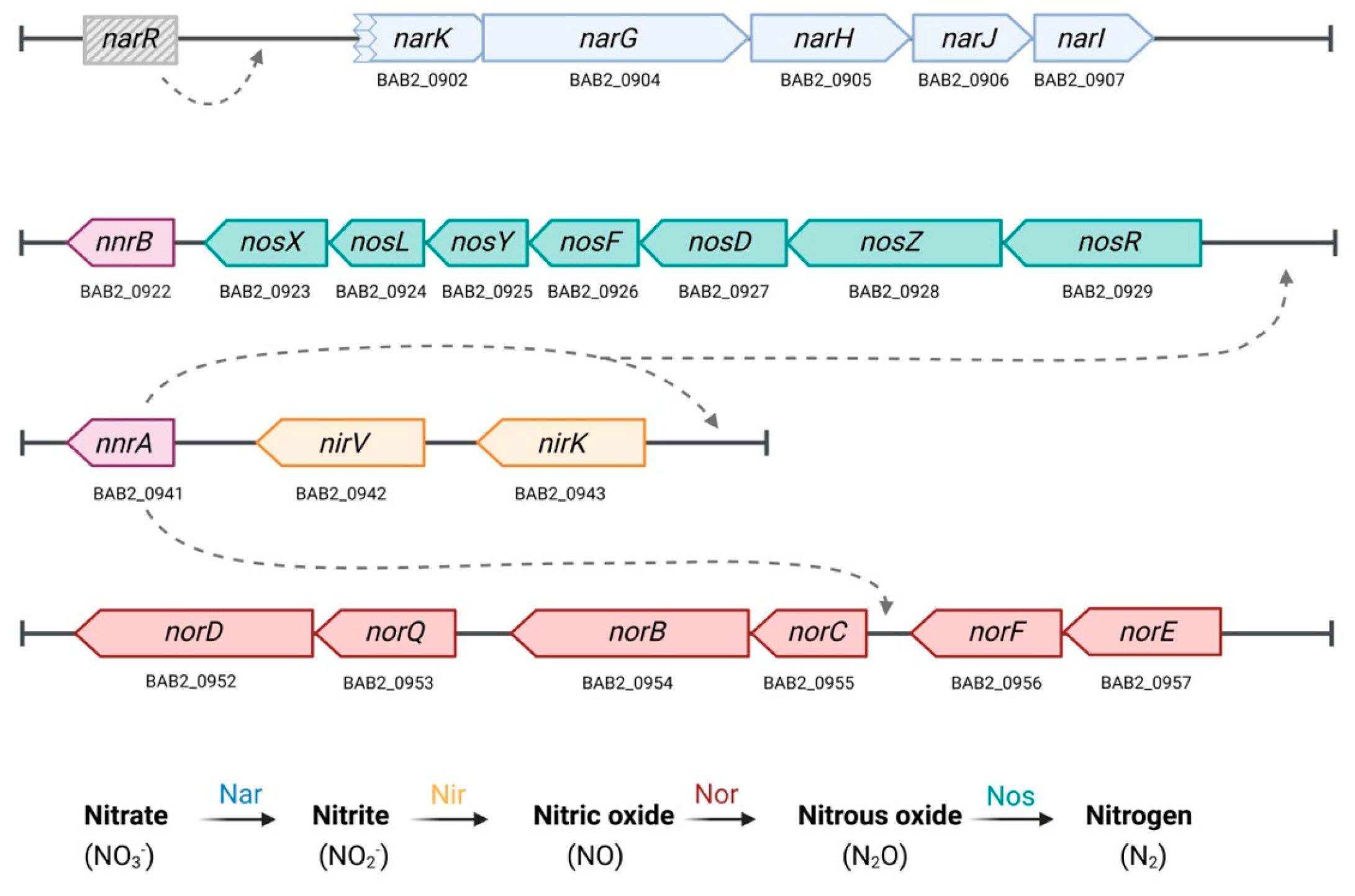

3. Results and Discussion

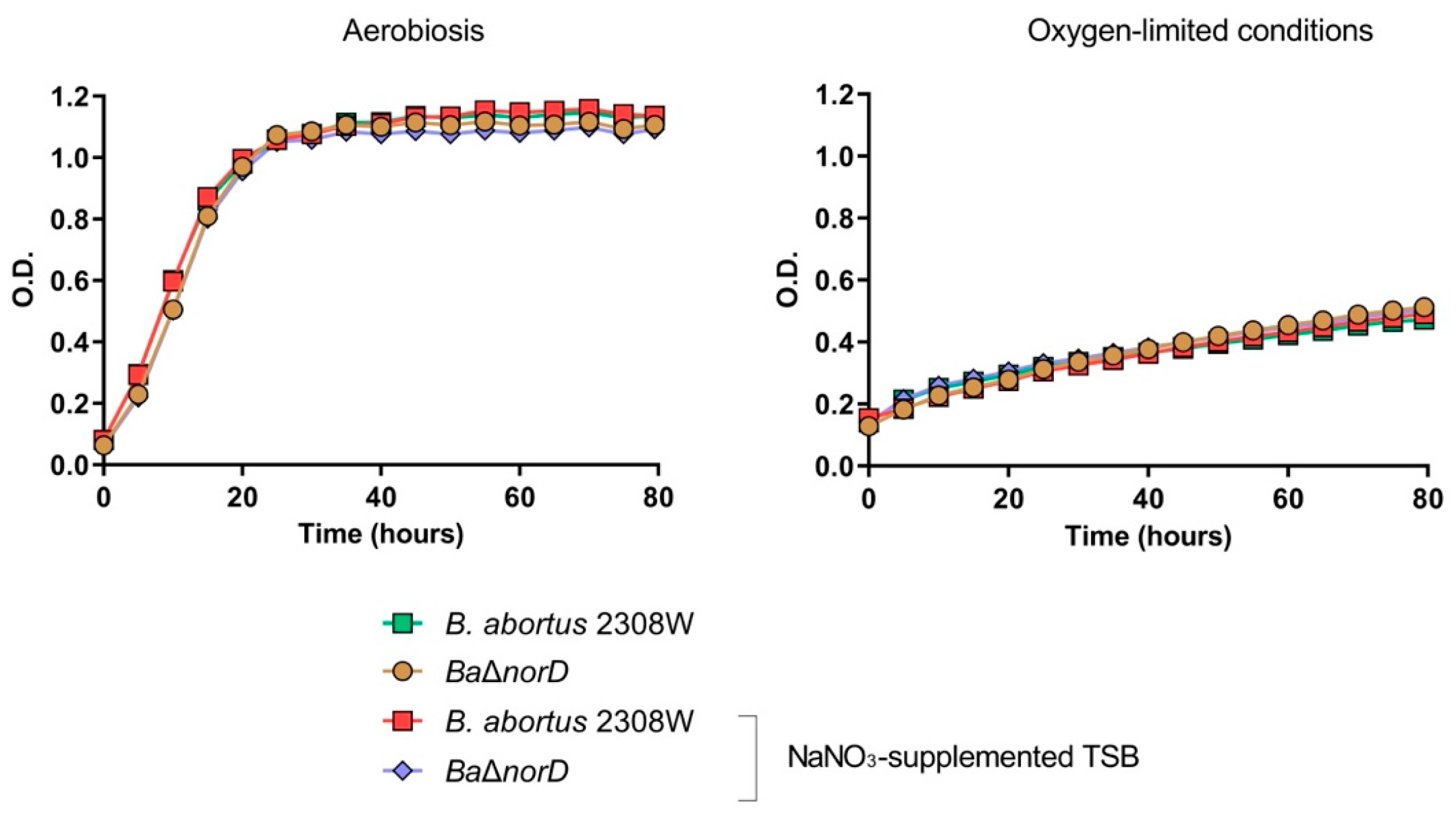

3.1. NorD Is Dispensable for Brucella abortus 2308W Growth and Survival Under Nitrate Reduction Promoting Conditions

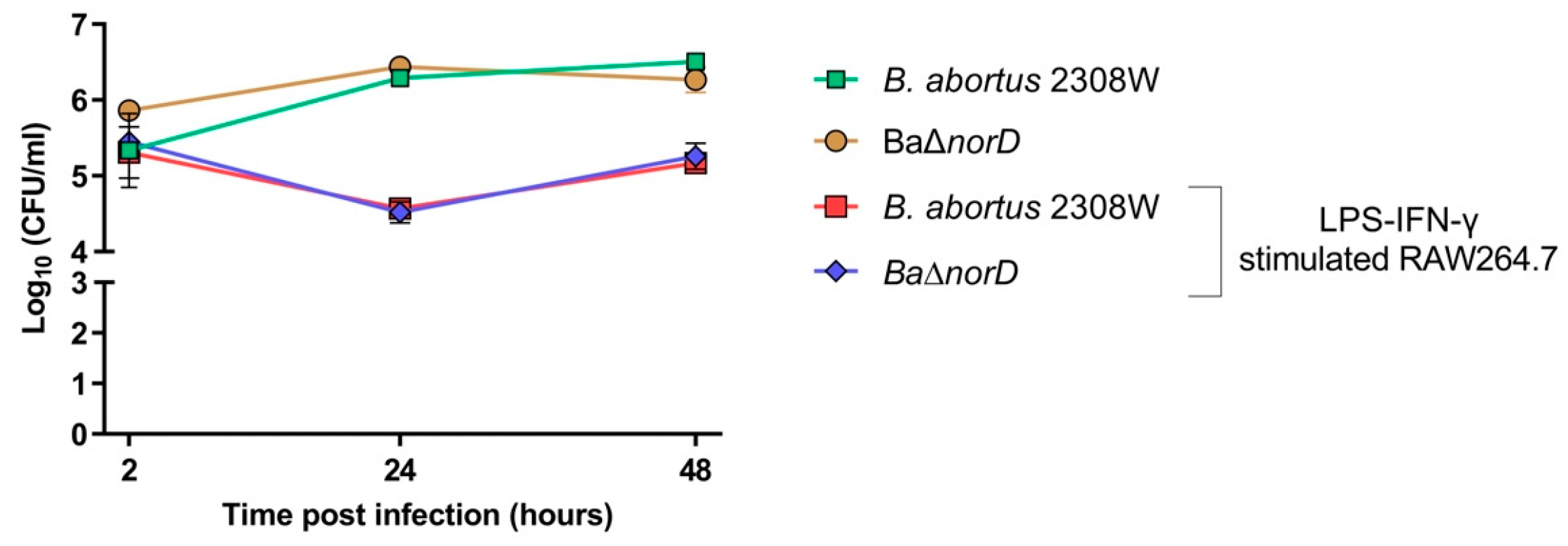

3.2. Deletion of NorD Does Not Affect Resistance of Brucella abortus 2308W to Nitrosative Stress

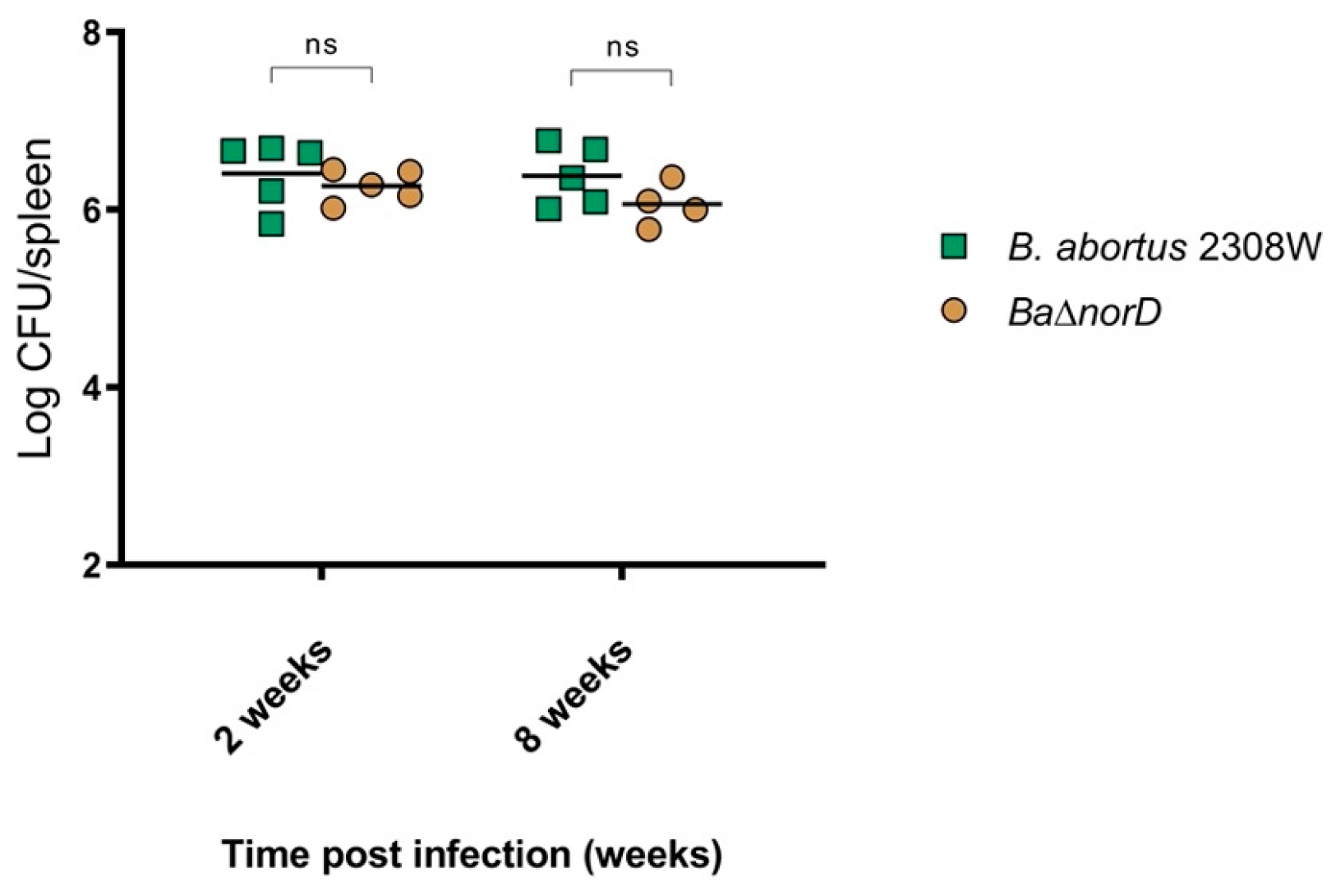

3.3. NorD Is Not Required for B. abortus 2308W Survival or Replication in Macrophages or in the Mouse Model

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| BSS | Buffered Saline Solution |

| BSL3 | Biosafety Level 3 |

| CFU | Colony Forming Unit |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DPBS | Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| iNOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| Km | Kanamycin |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MOI | Multiplicity of Infection |

| NaNO3 | Sodium Nitrate |

| Nal | Nalidixic Acid |

| N2 | Dinitrogen Gas |

| N2O | Nitrous Oxide |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NO2− | Nitrite |

| NO3− | Nitrate |

| OD600 | Optical Density at 600 nm |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TSA | Tryptic Soy Agar |

| TSB | Tryptic Soy Broth |

References

- Pappas, G.; Papadimitriou, P.; Akritidis, N.; Christou, L.; Tsianos, E. V The New Global Map of Human Brucellosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2006, 6, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, J.J.; Grace, D.; Zinstagg, J. Economics of Brucellosis Impact and Control in Low-Income Countries. Rev. Sci. Tech. De L’oie 2013, 32, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler-Lloréns, P.F.; Quance, C.R.; Lawhon, S.D.; Stuber, T.P.; Edwards, J.F.; Ficht, T.A.; Robbe-Austerman, S.; O’Callaghan, D.; Keriel, A. A Brucella spp. Isolate from a Pac-Man Frog (Ceratophrys ornata) Reveals Characteristics Departing from Classical Brucellae. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, E.; Blasco, J.M.; Letesson, J.J.; Gorvel, J.P.; Moriyón, I. Pathogenicity and Its Implications in Taxonomy: The Brucella and Ochrobactrum Case. Pathogens 2022, 11, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Occhialini, A.; Hofreuter, D.; Ufermann, C.-M.; Al Dahouk, S.; Köhler, S. The Retrospective on Atypical Brucella Species Leads to Novel Definitions. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbel, M.J.; Alton, G.G.; Banai, M.; Díaz, R.; Dranovskaia, B.A.; Elberg, S.S.; Garin-Bastuji, B.; Kolar, J.; Mantovani, A.; Mousa, A.M.; et al. Brucellosis in Humans and Animals; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; ISBN 9241547138. [Google Scholar]

- Rubach, M.P.; Halliday, J.E.B.; Cleaveland, S.; Crump, J.A. Brucellosis in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 26, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celli, J. The Intracellular Life Cycle of Brucella spp. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Álvarez, R.; Arce-Gorvel, V.; Iriarte, M.; Manček-Keber, M.; Barquero-Calvo, E.; Palacios-Chaves, L.; Chacón-Díaz, C.; Chaves-Olarte, E.; Martirosyan, A.; von Bargen, K.; et al. The Lipopolysaccharide Core of Brucella abortus Acts as a Shield Against Innate Immunity Recognition. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquero-Calvo, E.; Conde-Álvarez, R.; Chacón-Díaz, C.; Quesada-Lobo, L.; Martirosyan, A.; Guzmán-Verri, C.; Iriarte, M.; Mancek-Keber, M.; Jerala, R.; Gorvel, J.P.; et al. The Differential Interaction of Brucella and Ochrobactrum with Innate Immunity Reveals Traits Related to the Evolution of Stealthy Pathogens. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, 5893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquero-Calvo, E.; Chaves-Olarte, E.; Weiss, D.S.; Guzmán-Verri, C.; Chacón-Díaz, C.; Rucavado, A.; Moriyón, I.; Moreno, E. Brucella abortus Uses a Stealthy Strategy to Avoid Activation of the Innate Immune System during the Onset of Infection. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machelart, A.; Willemart, K.; Zúñiga-Ripa, A.; Godard, T.; Plovier, H.; Wittmann, C.; Moriyón, I.; De Bolle, X.; Van Schaftingen, E.; Letesson, J.-J.; et al. Convergent Evolution of Zoonotic Brucella Species toward the Selective Use of the Pentose Phosphate Pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 26374–26381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga-Ripa, A.; Barbier, T.; Conde-Álvarez, R.; Martínez-Gómez, E.; Palacios-Chaves, L.; Gil-Ramírez, Y.; Grilló, M.J.; Letesson, J.-J.; Iriarte, M.; Moriyon, I. Brucella abortus Depends on Pyruvate Phosphate Dikinase and Malic Enzyme but Not on Fbp and GlpX Fructose-1,6-Bisphosphatases for Full Virulence in Laboratory Models. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 3045–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, E.; Moriyón, I. The Genus Brucella. In The Prokaryotes: A Handbook on the Biology of Bacteria; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 5, pp. 315–456. [Google Scholar]

- Rest, R.F.; Robertson, D.C. Glucose Transport in Brucella abortus. J. Bacteriol. 1974, 118, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickett, M.J.; Nelson, E.L. Speciation within the Genus Brucella. III. Nitrate Reduction and Nitrite Toxicity Tests. J. Bacteriol. 1954, 68, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zobell, C.E.; Meyer, K.F. Metabolism Studies on the Brucella Group VI. Nitrate and Nitrite Reduction. J. Infect. Dis. 1932, 51, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alton, G.G.; Jones, L.M.; Angus, R.D.; Verger, J.-M. Techniques for the Brucellosis Laboratory; INRA: Paris, France, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneau, S.; Moussa, S.; Barbier, T.; Conde-Álvarez, R.; Zúñiga-Ripa, A.; Moriyón, I.; Letesson, J.-J. Brucella, Nitrogen and Virulence. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 42, 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freddi, L.; de la Garza-García, J.A.; Al Dahouk, S.; Occhialini, A.; Köhler, S. Brucella spp. Are Facultative Anaerobic Bacteria under Denitrifying Conditions. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e02767-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.C. Antimicrobial Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species: Concepts and Controversies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, M.; ter Beek, J.; Hosler, J.P.; Ädelroth, P. The Insertion of the Non-Heme FeB Cofactor into Nitric Oxide Reductase from P. Denitrificans Depends on NorQ and NorD Accessory Proteins. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 2018, 1859, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperry, J.F.; Robertson, D.C. Erythritol Catabolism by Brucella abortus. J. Bacteriol. 1975, 121, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rest, R.F.; Robertson, D.C. Characterization of the Electron Transport System in Brucella abortus. J. Bacteriol. 1975, 122, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loisel-Meyer, S.; Jiménez de Bagüés, M.P.; Bassères, E.; Dornand, J.; Köhler, S.; Liautard, J.-P.; Jubier-Maurin, V. Requirement of NorD for Brucella suis Virulence in a Murine Model of In Vitro and In Vivo Infection. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 1973–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haine, V.; Dozot, M.; Dornand, J.; Letesson, J.-J.; De Bolle, X. NnrA Is Required for Full Virulence and Regulates Several Brucella melitensis Denitrification Genes. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 1615–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Clapp, B.; Thornburg, T.; Hoffman, C.; Pascual, D.W. Vaccination with a ΔnorD ΔznuA Brucella abortus Mutant Confers Potent Protection against Virulent Challenge. Vaccine 2016, 34, 5290–5297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hoffman, C.; Yang, X.; Clapp, B.; Pascual, D.W. Targeting Resident Memory T Cell Immunity Culminates in Pulmonary and Systemic Protection against Brucella Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, P.; Wilson, J.B. The Nutrition of Brucellae: Growth in Simple Chemically Defined Media. J. Bacteriol. 1948, 56, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goujon, M.; McWilliam, H.; Li, W.; Valentin, F.; Squizzato, S.; Paern, J.; Lopez, R. A New Bioinformatics Analysis Tools Framework at EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, W695–W699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, F.; Wilm, A.; Dineen, D.; Gibson, T.J.; Karplus, K.; Li, W.; Lopez, R.; McWilliam, H.; Remmert, M.; Söding, J.; et al. Fast, Scalable Generation of High-Quality Protein Multiple Sequence Alignments Using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011, 7, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.L.; Mekalanos, J.J. A Novel Suicide Vector and Its Use in Construction of Insertion Mutations: Osmoregulation of Outer Membrane Proteins and Virulence Determinants in Vibrio cholerae Requires ToxR. J. Bacteriol. 1988, 170, 2575–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R.; Priefer, U.; Pühler, A. A Broad Host Range Mobilization System for in Vivo Genetic Engineering: Transposon Mutagenesis in Gram Negative Bacteria. Nat. Biotechnol. 1983, 1, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangari, F.; Agüero, J. Mutagenesis of Brucella abortus: Comparative Efficiency of Three Transposon Delivery Systems. Microb. Pathog. 1991, 11, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Esquivel, M.; Ruiz-Villalobos, N.; Castillo-Zeledón, A.; Jiménez-Rojas, C.; Roop, R.M., II; Comerci, D.J.; Barquero-Calvo, E.; Chacón-Díaz, C.; Caswell, C.C.; Baker, K.S.; et al. Brucella abortus Strain 2308 Wisconsin Genome: Importance of the Definition of Reference Strains. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilló, M.-J.; Blasco, J.M.; Gorvel, J.P.; Moriyón, I.; Moreno, E. What Have We Learned from Brucellosis in the Mouse Model? Vet. Res. 2012, 43, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chain, P.S.G.; Comerci, D.J.; Tolmasky, M.E.; Larimer, F.W.; Malfatti, S.A.; Vergez, L.M.; Aguero, F.; Land, M.L.; Ugalde, R.A.; García, E.; et al. Whole-Genome Analyses of Speciation Events in Pathogenic Brucellae. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 8353–8361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M.; Takeda, H.; Kato, H.E.; Doki, S.; Ito, K.; Maturana, A.D.; Ishitani, R.; Nureki, O. Structural Basis for Dynamic Mechanism of Nitrate/Nitrite Antiport by NarK. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochgräfe, F.; Wolf, C.; Fuchs, S.; Liebeke, M.; Lalk, M.; Engelmann, S.; Hecker, M. Nitric Oxide Stress Induces Different Responses but Mediates Comparable Protein Thiol Protection in Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 4997–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudill, M.T.; Stoyanof, S.T.; Caswell, C.C. Quorum Sensing LuxR Proteins VjbR and BabR Jointly Regulate Brucella abortus Survival during Infection. J. Bacteriol. 2025, 207, e00527-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Qureshi, N.; Soeurt, N.; Splitter, G. High Levels of Nitric Oxide Production Decrease Early but Increase Late Survival of Brucella abortus in Macrophages. Microb. Pathog. 2001, 31, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestrate, P.; Dricot, A.; Delrue, R.-M.; Lambert, C.; Martinelli, V.; De Bolle, X.; Letesson, J.-J.; Tibor, A. Attenuated Signature-Tagged Mutagenesis Mutants of Brucella Melitensis Identified during the Acute Phase of Infection in Mice. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 7053–7060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, C.A.; Galindo, C.L.; Garner, H.R.; Adams, L.G. Transcriptional Profile of the Intracellular Pathogen Brucella melitensis Following HeLa Cells Infection. Microb. Pathog. 2011, 51, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, S.; Foulongne, V.; Ouahrani-Bettache, S.; Bourg, G.; Teyssier, J.; Ramuz, M.; Liautard, J.-P. The Analysis of the Intramacrophagic Virulome of Brucella suis Deciphers the Environment Encountered by the Pathogen inside the Macrophage Host Cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 15711–15716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Lim, J.J.; Lee, J.J.; Kim, D.G.; Lee, H.J.; Min, W.; Kim, K.D.; Chang, H.H.; Rhee, M.H.; Watarai, M.; et al. Identification of Genes Contributing to the Intracellular Replication of Brucella abortus within HeLa and RAW 264.7 Cells. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 158, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-H.; Rajashekara, G.; Splitter, G.A.; Shapleigh, J.P. Denitrification Genes Regulate Brucella Virulence in Mice. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 6025–6031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rasheed, F.; Zúñiga-Ripa, A.; Salvador-Bescós, M.; Irshad, H.; Peña-Villafruela, R.; Muñoz, P.M.; de Miguel, M.J.; Ali, Q.; Conde-Álvarez, R.; Khan, S.-u.-H. Disruption of the Nitric Oxide Reductase Operon via norD Deletion Does Not Affect Brucella abortus 2308W Virulence. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2875. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122875

Rasheed F, Zúñiga-Ripa A, Salvador-Bescós M, Irshad H, Peña-Villafruela R, Muñoz PM, de Miguel MJ, Ali Q, Conde-Álvarez R, Khan S-u-H. Disruption of the Nitric Oxide Reductase Operon via norD Deletion Does Not Affect Brucella abortus 2308W Virulence. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2875. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122875

Chicago/Turabian StyleRasheed, Faisal, Amaia Zúñiga-Ripa, Miriam Salvador-Bescós, Hamid Irshad, Raquel Peña-Villafruela, Pilar M. Muñoz, María Jesús de Miguel, Qurban Ali, Raquel Conde-Álvarez, and Saeed-ul-Hassan Khan. 2025. "Disruption of the Nitric Oxide Reductase Operon via norD Deletion Does Not Affect Brucella abortus 2308W Virulence" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2875. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122875

APA StyleRasheed, F., Zúñiga-Ripa, A., Salvador-Bescós, M., Irshad, H., Peña-Villafruela, R., Muñoz, P. M., de Miguel, M. J., Ali, Q., Conde-Álvarez, R., & Khan, S.-u.-H. (2025). Disruption of the Nitric Oxide Reductase Operon via norD Deletion Does Not Affect Brucella abortus 2308W Virulence. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2875. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122875