Modulation of Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis in Germ-Free Mice by Enterococcus faecalis Monocolonization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Monocolonization

2.3. DSS Colitis Model

2.4. Sample Collection and Processing

2.5. Hematological Parameters

2.6. Histology

2.7. Albumin and Calprotectin Measurements

2.8. DNA Extraction and Real-Time Quantitative PCR of E. faecalis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. E. faecalis Monocolonization and Colitis Induction

3.2. E. faecalis-Colonization Alters Colitis-Related Disease Activity and Physiological Parameters in DSS-Treated Mice

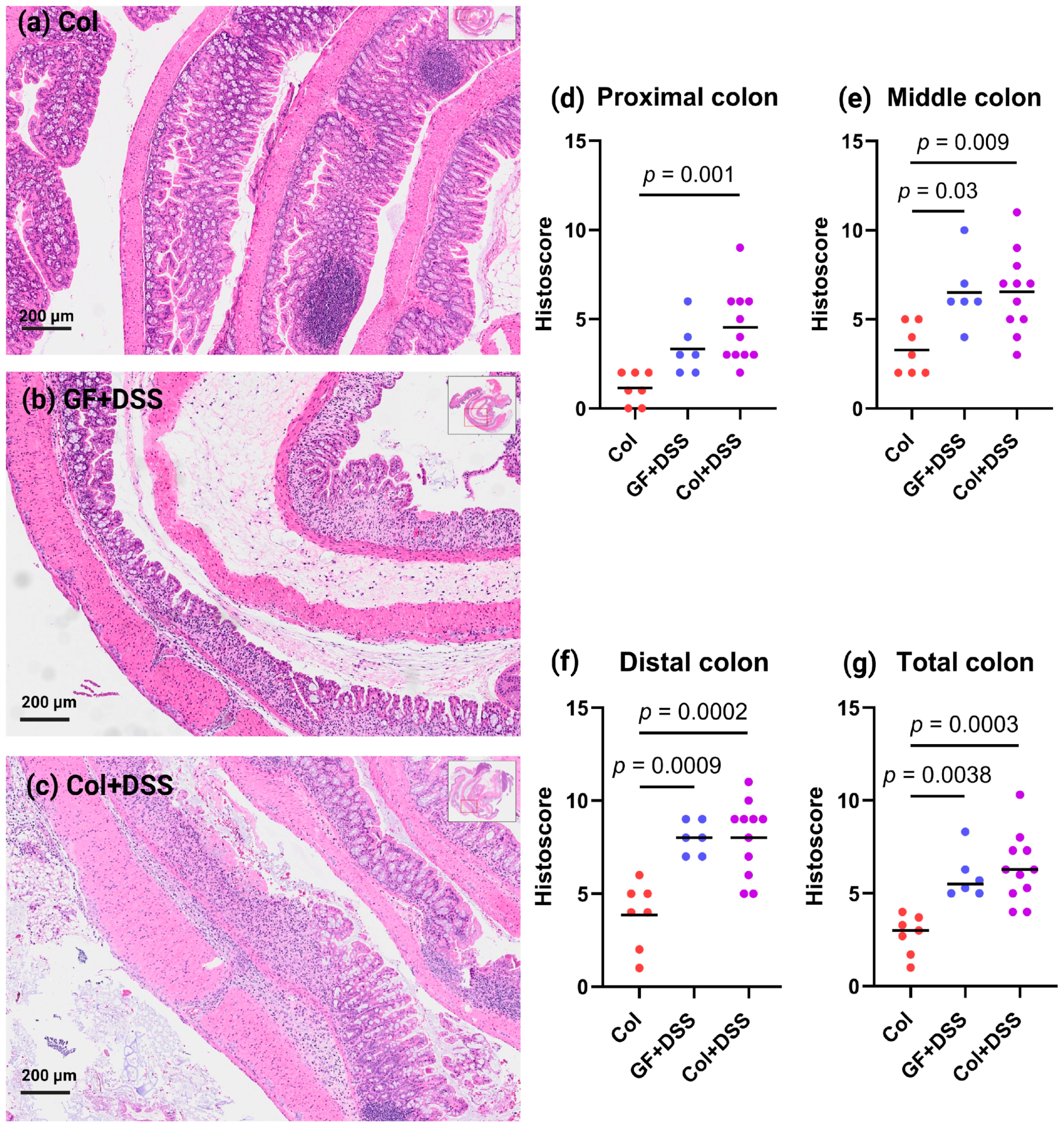

3.3. DSS Treatment of GF and E. faecalis-Monocolonized Mice Induces Similar Histology Alterations

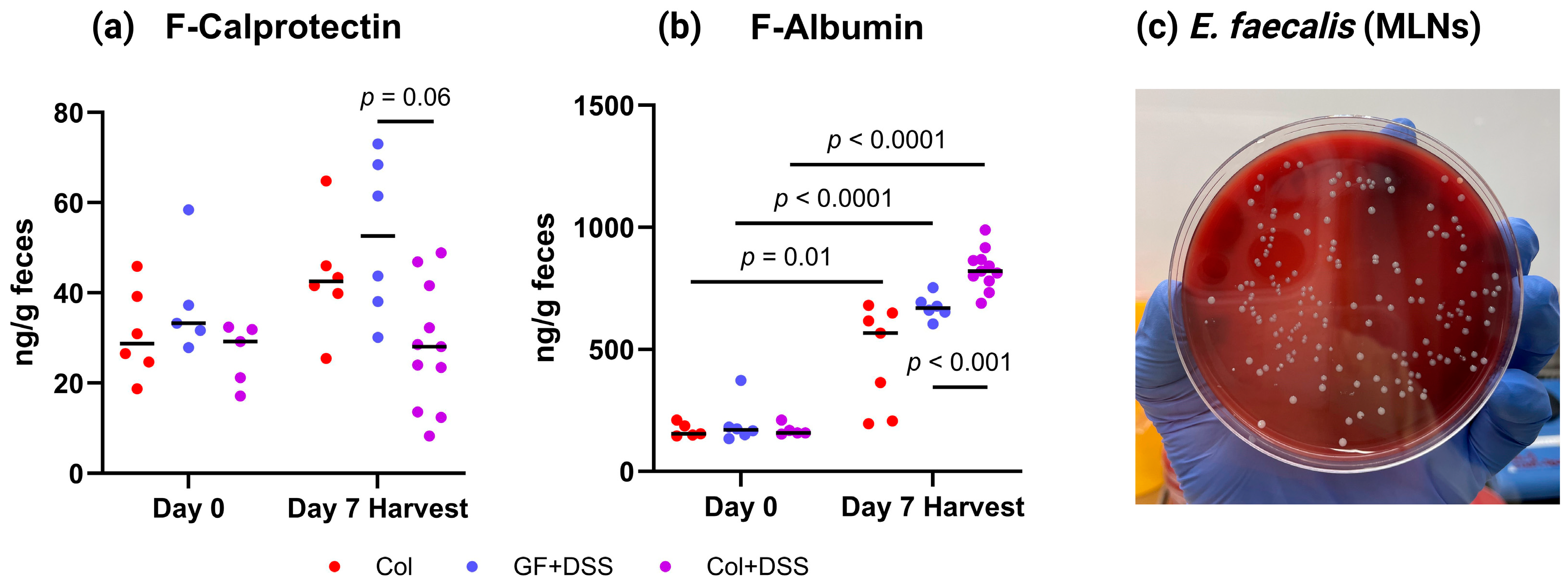

3.4. E. faecalis Alters Fecal Calprotectin and Albumin Levels and Translocates to Mesenteric Lymph Nodes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| E. faecalis | Enterococcus faecalis |

| GF | Germ-free |

| DSS | Dextran sulfate sodium |

| MLNs | Mesenteric lymph nodes |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| IL | Interleukin |

| CFU | Colony-forming units |

References

- Sands, B.E. From symptom to diagnosis: Clinical distinctions among various forms of intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology 2004, 126, 1518–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartor, R.B. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadakis, K.A.; Targan, S.R. Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 2000, 51, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Martin, E.; Hernandez-Suarez, L.; Muñoz-Villafranca, C.; Martin-Souto, L.; Astigarraga, E.; Ramirez-Garcia, A.; Barreda-Gómez, G. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comprehensive Analysis of Molecular Bases, Predictive Biomarkers, Diagnostic Methods, and Therapeutic Options. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooser, C.; Gomez de Aguero, M.; Ganal-Vonarburg, S.C. Standardization in host-microbiota interaction studies: Challenges, gnotobiology as a tool, and perspective. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2018, 44, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, F.; Backhed, F. The gut microbiota—Masters of host development and physiology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perse, M.; Cerar, A. Dextran sodium sulphate colitis mouse model: Traps and tricks. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 718617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, S.; Neufert, C.; Weigmann, B.; Neurath, M.F. Chemically induced mouse models of intestinal inflammation. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroui, H.; Ingersoll, S.A.; Liu, H.C.; Baker, M.T.; Ayyadurai, S.; Charania, M.A.; Laroui, F.; Yan, Y.; Sitaraman, S.V.; Merlin, D. Dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) induces colitis in mice by forming nano-lipocomplexes with medium-chain-length fatty acids in the colon. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassaing, B.; Aitken, J.D.; Malleshappa, M.; Vijay-Kumar, M. Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2014, 104, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, Y.; Bamba, T.; Mukaisho, K.-I.; Kanauchi, O.; Ban, H.; Bamba, S.; Andoh, A.; Fujiyama, Y.; Hattori, T.; Sugihara, H. Dextran sulfate sodium administered orally is depolymerized in the stomach and induces cell cycle arrest plus apoptosis in the colon in early mouse colitis. Oncol. Rep. 2012, 28, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, J.; Chen, S.F.; Hollander, D. Effects of dextran sulphate sodium on intestinal epithelial cells and intestinal lymphocytes. Gut 1996, 39, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tlaskalova-Hogenova, H.; Stepankova, R.; Kozakova, H.; Hudcovic, T.; Vannucci, L.; Tuckova, L.; Rossmann, P.; Hrncir, T.; Kverka, M.; Zakostelska, Z.; et al. The role of gut microbiota (commensal bacteria) and the mucosal barrier in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases and cancer: Contribution of germ-free and gnotobiotic animal models of human diseases. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2011, 8, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, K.; Phillips, C. The ecology, epidemiology and virulence of Enterococcus. Microbiology 2009, 155, 1749–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balish, E.; Warner, T. Enterococcus faecalis induces inflammatory bowel disease in interleukin-10 knockout mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 160, 2253–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, C.M.; Holzapfel, W.H.; Stiles, M.E. Enterococci at the crossroads of food safety? Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1999, 47, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulquie Moreno, M.R.; Sarantinopoulos, P.; Tsakalidou, E.; De Vuyst, L. The role and application of enterococci in food and health. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 106, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semedo, T.; Santos, M.A.; Lopes, M.F.; Marques, J.J.; Crespo, M.T.; Tenreiro, R. Virulence factors in food, clinical and reference Enterococci: A common trait in the genus? Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 26, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaoglu, G.; Orstavik, D. Virulence factors of Enterococcus faecalis: Relationship to endodontic disease. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2004, 15, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hibberd, M.L.; Pettersson, S.; Lee, Y.K. Enterococcus faecalis from healthy infants modulates inflammation through MAPK signaling pathways. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocvirk, S.; Sava, I.G.; Lengfelder, I.; Lagkouvardos, I.; Steck, N.; Roh, J.H.; Tchaptchet, S.; Bao, Y.; Hansen, J.J.; Huebner, J.; et al. Surface-Associated Lipoproteins Link Enterococcus faecalis Virulence to Colitogenic Activity in IL-10-Deficient Mice Independent of Their Expression Levels. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FELASA Working Group on Revision of Guidelines for Health Monitoring of Rodents and Rabbits; Mähler, M.; Berard, M.; Feinstein, R.; Gallagher, A.; Illgen-Wilcke, B.; Pritchett-Corning, K.; Raspa, M. FELASA recommendations for the health monitoring of mouse, rat, hamster, guinea pig and rabbit colonies in breeding and experimental units. Lab. Anim. 2014, 48, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, M.E.; Uwiera, R.R.E.; Inglis, G.D. Housing Gnotobiotic Mice in Conventional Animal Facilities. Curr. Protoc. Mouse Biol. 2019, 9, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, H.S.; Murthy, S.N.; Shah, R.S.; Sedergran, D.J. Clinicopathologic study of dextran sulfate sodium experimental murine colitis. Lab. Investig. 1993, 69, 238–249. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8350599/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Bang, B.; Lichtenberger, L.M. Methods of Inducing Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Mice. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2016, 72, 5–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankhead, P.; Loughrey, M.B.; Fernández, J.A.; Dombrowski, Y.; McArt, D.G.; Dunne, P.D.; McQuaid, S.; Gray, R.T.; Murray, L.J.; Coleman, H.G.; et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, W.S.; Lord, G.M.; Punit, S.; Lugo-Villarino, G.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Ito, S.; Glickman, J.N.; Glimcher, L.H. Communicable ulcerative colitis induced by T-bet deficiency in the innate immune system. Cell 2007, 131, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, M.; Weigmann, B.; Finotto, S.; Glickman, J.; Nieuwenhuis, E.; Iijima, H.; Mizoguchi, A.; Mizoguchi, E.; Mudter, J.; Galle, P.; et al. The transcription factor T-bet regulates mucosal T cell activation in experimental colitis and Crohn’s disease. J. Exp. Med. 2002, 195, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, C.L.; Jechorek, R.P.; Erlandsen, S.L. Evidence for the translocation of Enterococcus faecalis across the mouse intestinal tract. J. Infect. Dis. 1990, 162, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilpern, D.; Szilagyi, A. Manipulation of intestinal microbial flora for therapeutic benefit in inflammatory bowel diseases: Review of clinical trials of probiotics, pre-biotics and synbiotics. Rev. Recent Clin. Trials 2008, 3, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damman, C.J.; Miller, S.I.; Surawicz, C.M.; Zisman, T.L. The microbiome and inflammatory bowel disease: Is there a therapeutic role for fecal microbiota transplantation? Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 107, 1452–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, L.J.; Cho, J.H.; Gevers, D.; Chu, H. Genetic Factors and the Intestinal Microbiome Guide Development of Microbe-Based Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 2174–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitajima, S.; Morimoto, M.; Sagara, E.; Shimizu, C.; Ikeda, Y. Dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in germ-free IQI/Jic mice. Exp. Anim. 2001, 50, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslowski, K.M.; Vieira, A.T.; Ng, A.; Kranich, J.; Sierro, F.; Yu, D.; Schilter, H.C.; Rolph, M.S.; Mackay, F.; Artis, D.; et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature 2009, 461, 1282–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-C.; Ching, Y.-H.; Wang, Y.-C.; Liu, J.-Y.; Li, Y.-P.; Huang, Y.-T.; Chuang, H.-L. Monocolonization of germ-free mice with Bacteroides fragilis protects against dextran sulfate sodium-induced acute colitis. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 675786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Niu, M.; Bi, J.; Du, N.; Liu, S.; Yang, K.; Li, H.; Yao, J.; Du, Y.; Duan, Y. Protective effects of a new generation of probiotic Bacteroides fragilis against colitis in vivo and in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Hudcovic, T.; Mrazek, J.; Kozakova, H.; Srutkova, D.; Schwarzer, M.; Tlaskalova-Hogenova, H.; Kostovcik, M.; Kverka, M. Development of gut inflammation in mice colonized with mucosa-associated bacteria from patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut Pathog. 2015, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golinska, E.; Tomusiak, A.; Gosiewski, T.; Więcek, G.; Machul, A.; Mikołajczyk, D.; Bulanda, M.; Heczko, P.B.; Strus, M. Virulence factors of Enterococcus strains isolated from patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 3562–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.C.; Tonkonogy, S.L.; Albright, C.A.; Tsang, J.; Balish, E.J.; Braun, J.; Huycke, M.M.; Sartor, R.B. Variable phenotypes of enterocolitis in interleukin 10-deficient mice monoassociated with two different commensal bacteria. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, 891–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, A.M.T.; Dale, J.L.; Chen, Y.; Manias, D.A.; Quaintance, K.E.G.; Karau, M.K.; Kashyap, P.C.; Patel, R.; Wells, C.L.; Dunny, G.M. Enterococcus faecalis readily colonizes the entire gastrointestinal tract and forms biofilms in a germ-free mouse model. Virulence 2017, 8, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, J.; Saliba, Y.; Hajal, J.; Smayra, V.; Bakhos, J.-J.; Sayegh, R.; Fares, N. Circadian Rhythm Disruption Aggravates DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice with Fecal Calprotectin as a Marker of Colitis Severity. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 3122–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Are, A.; Aronsson, L.; Wang, S.; Greicius, G.; Lee, Y.K.; Gustafsson, J.; Pettersson, S.; Arulampalam, V. Enterococcus faecalis from newborn babies regulate endogenous PPARgamma activity and IL-10 levels in colonic epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1943–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takada, Y.; Hisamatsu, T.; Kamada, N.; Kitazume, M.T.; Honda, H.; Oshima, Y.; Saito, R.; Takayama, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Chinen, H.; et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 contributes to gut homeostasis and intestinal inflammation by composition of IL-10-producing regulatory macrophage subset. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 2671–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Nakagawasai, O.; Nemoto, W.; Odaira, T.; Sakuma, W.; Onogi, H.; Nishijima, H.; Furihata, R.; Nemoto, Y.; Iwasa, H.; et al. Effect of Enterococcus faecalis 2001 on colitis and depressive-like behavior in dextran sulfate sodium-treated mice: Involvement of the brain-gut axis. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hong, G.; Huang, C.; Qian, W.; Bai, T.; Song, J.; Song, Y.; Hou, X. Probiotic mixtures with aerobic constituent promoted the recovery of multi-barriers in DSS-induced chronic colitis. Life Sci. 2020, 240, 117089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-L.; Wang, X.-H.; Cui, Y.; Lian, G.-H.; Zhang, J.; Ouyang, C.-H.; Lu, F.-G. Therapeutic effects of four strains of probiotics on experimental colitis in mice. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, U.; Jiang, C.; Yan, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, B.; Xing, J.; Niu, T.; Shi, C.; Wang, C. Inhibitory Effect of Lactococcus and Enterococcus faecalis on Citrobacter Colitis in Mice. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Messlik, A.; Kim, S.C.; Sartor, R.B.; Haller, D. Impact of a probiotic Enterococcus faecalis in a gnotobiotic mouse model of experimental colitis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seishima, J.; Iida, N.; Kitamura, K.; Yutani, M.; Wang, Z.; Seki, A.; Yamashita, T.; Sakai, Y.; Honda, M.; Yamashita, T.; et al. Gut-derived Enterococcus faecium from ulcerative colitis patients promotes colitis in a genetically susceptible mouse host. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vestad, B.; Hanzely, P.; Karaliūtė, I.; Ramberg, O.; Skiecevičienė, J.; Lukoševičius, R.; Bjørnholt, J.V.; Holm, K.; Kupčinskas, J.; Rasmussen, H.; et al. Modulation of Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis in Germ-Free Mice by Enterococcus faecalis Monocolonization. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2864. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122864

Vestad B, Hanzely P, Karaliūtė I, Ramberg O, Skiecevičienė J, Lukoševičius R, Bjørnholt JV, Holm K, Kupčinskas J, Rasmussen H, et al. Modulation of Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis in Germ-Free Mice by Enterococcus faecalis Monocolonization. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2864. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122864

Chicago/Turabian StyleVestad, Beate, Petra Hanzely, Indrė Karaliūtė, Oda Ramberg, Jurgita Skiecevičienė, Rokas Lukoševičius, Jørgen V. Bjørnholt, Kristian Holm, Juozas Kupčinskas, Henrik Rasmussen, and et al. 2025. "Modulation of Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis in Germ-Free Mice by Enterococcus faecalis Monocolonization" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2864. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122864

APA StyleVestad, B., Hanzely, P., Karaliūtė, I., Ramberg, O., Skiecevičienė, J., Lukoševičius, R., Bjørnholt, J. V., Holm, K., Kupčinskas, J., Rasmussen, H., Hov, J. R., & Melum, E. (2025). Modulation of Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis in Germ-Free Mice by Enterococcus faecalis Monocolonization. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2864. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122864

_Di_Marco.png)