Clinical Manifestations, Antifungal Susceptibilities, and Outcome of Ocular Infections Caused by Purpureocillium lilacinum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pathogen Isolation and Identification

2.2. Antifungal Susceptibility Testing

2.3. Outcome Definition

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

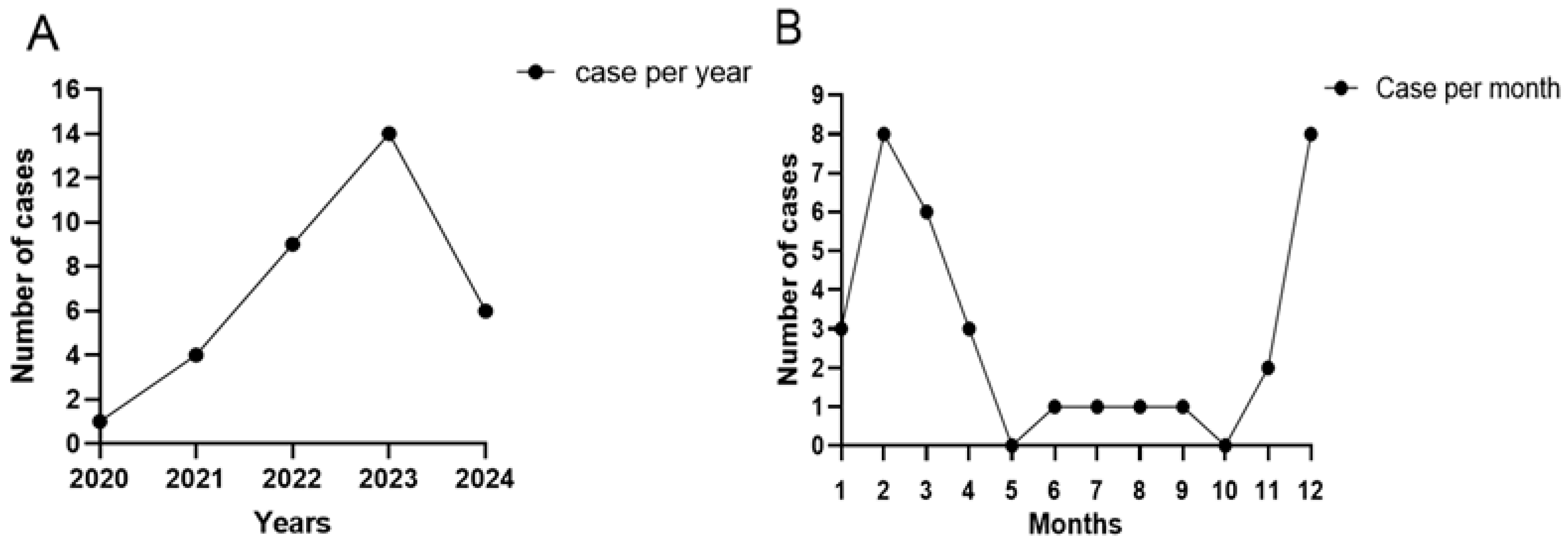

3.1. Clinical Features

3.2. Treatment and Outcome

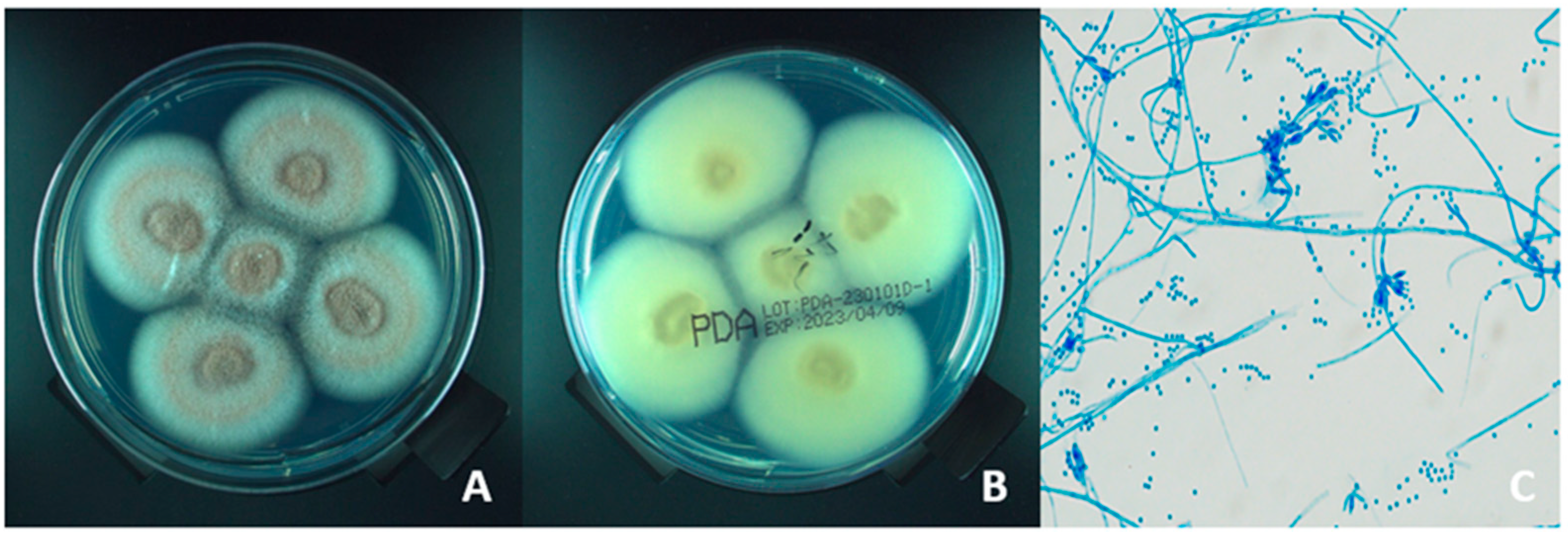

3.3. Clinical Manifestations and Microbiological Identification

3.4. Antifungal Susceptivity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Slowik, M.; Biernat, M.M.; Urbaniak-Kujda, D.; Kapelko-Slowik, K.; Misiuk-Hojlo, M. Mycotic Infections of the Eye. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 24, 1113–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.; Leck, A.K.; Gichangi, M.; Burton, M.J.; Denning, D.W. The global incidence and diagnosis of fungal keratitis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, e49–e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, S.; Masoomi, A.; Ahmadikia, K.; Tabatabaei, S.A.; Soleimani, M.; Rezaie, S.; Ghahvechian, H.; Banafsheafshan, A. Fungal keratitis: An overview of clinical and laboratory aspects. Mycoses 2018, 61, 916–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usuda, D.; Furukawa, D.; Imaizumi, R.; Ono, R.; Kaneoka, Y.; Nakajima, E.; Sugawara, Y.; Shimizu, R.; Sakurai, R.; Matsubara, S.; et al. Purpureocillium lilacinum: A minireview. World J. Clin. Cases 2025, 13, 108582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marti, G.A.; Lastra, C.C.L.; Pelizza, S.A.; García, J.J. Isolation of Paecilomyces lilacinus (Thom) Samson (Ascomycota: Hypocreales) from the Chagas disease vector, Triatoma infestans Klug (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in an endemic area in Argentina. Mycopathologia 2006, 162, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiewnick, S.; Sikora, R.A. Efficacy of Paecilomyces lilacinus (strain 251) for the control of root-knot nematodes. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2003, 68, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Hu, Q. Secondary Metabolites of Purpureocillium lilacinum. Molecules 2021, 27, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M.L.; Santos, D.O.; Souza Ide, C.; Neri, E.C.; Sequeira, D.C.; De Luca, P.M.; Borba Cde, M. Interaction of an opportunistic fungus Purpureocillium lilacinum with human macrophages and dendritic cells. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2014, 47, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, F.J.; Guarro, J. Clinical manifestations, treatment and outcome of Paecilomyces lilacinus infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2006, 12, 948–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Wilhelmus, K.R.; Matoba, A.Y.; Alexandrakis, G.; Miller, D.; Huang, A.J. Pathogenesis and outcome of Paecilomyces keratitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2009, 147, 691–696 e693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.K.; Amescua, G.; Miller, D.; Suh, L.H.; Delmonte, D.W.; Gibbons, A.; Alfonso, E.C.; Forster, R.K. Contact-Lens-Associated Purpureocillium Keratitis: Risk Factors, Microbiologic Characteristics, Clinical Course, and Outcomes. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 32, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, L.D.; Conrad, D. Retrospective case-series of Paecilomyces lilacinus ocular mycoses in Queensland, Australia. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.N.; Wang, H.; Hsueh, P.R.; Meis, J.F.; Chen, H.; Xu, Y.C. Endophthalmitis caused by Purpureocillium lilacinum. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2019, 52, 170–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, X.; Li, S.; Wang, T.; Jia, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Dong, C.; Shi, W. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes of rare genera fungal keratitis in China. Res. Sq. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zeng, F.; Zhang, J.; Qi, X.; Lu, X.; Ning, N.; Li, S.; Zhang, T.; Yuan, G.; Shi, W.; et al. Microbiological Characteristics and Risk Factors Involved in Progression from Fungal Keratitis with Hypopyon to Keratitis-Related Endophthalmitis. Mycopathologia 2023, 188, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, Y.; Chen, X.; Tan, Y.; Liu, X.; Duan, F.; Wu, K. Microbiological Profiles of Ocular Fungal Infection at an Ophthalmic Referral Hospital in Southern China: A Ten-Year Retrospective Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 3267–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, H.; Inuzuka, H.; Mochizuki, K.; Takahashi, N.; Muto, T.; Ohkusu, K.; Yaguchi, T.; Nishimura, K. Clinical manifestations, treatment and outcome of ocular infections caused by Paecilomyces species. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi 2012, 116, 613–622. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Hu, J. A retrospective study of the spectrum of fungal keratitis in southeastern China. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 9480–9487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Gupta, A.; Rudramurthy, S.M.; Paul, S.; Hallur, V.K.; Chakrabarti, A. Fungal Keratitis in North India: Spectrum of Agents, Risk Factors and Treatment. Mycopathologia 2016, 181, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luangsa-Ard, J.; Houbraken, J.; van Doorn, T.; Hong, S.B.; Borman, A.M.; Hywel-Jones, N.L.; Samson, R.A. Purpureocillium, a new genus for the medically important Paecilomyces lilacinus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2011, 321, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, Z.; AL-DIN, S.S. Influence of temperature and culture media on the growth of the fungus Paecilomyces lilacinus. Rev. Nématologie 1987, 10, 494. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.T.; Yeh, L.K.; Ma, D.H.K.; Lin, H.C.; Sun, C.C.; Tan, H.Y.; Chen, H.C.; Chen, S.Y.; Sun, P.L.; Hsiao, C.H. Paecilomyces/Purpureocillium keratitis: A consecutive study with a case series and literature review. Med. Mycol. 2020, 58, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Liu, X.; Ma, Z.; Yin, Y.; Sun, L.; Yang, L.; Zheng, Y. Fungal keratitis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis and prevention. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 138, 103802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toumasis, P.; Tsantes, A.G.; Tsiogka, A.; Samonis, G.; Vrioni, G. From Clinical Suspicion to Diagnosis: A Review of Diagnostic Approaches and Challenges in Fungal Keratitis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.P.; Horan, J.L.; Slechta, E.S.; Alexander, B.D.; Hanson, K.E. Complexities associated with the molecular and proteomic identification of Paecilomyces species in the clinical mycology laboratory. Med. Mycol. 2014, 52, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuthan, R.; Kurowska, A.K.; Izdebska, J.; Szaflik, J.P.; Lutynska, A.; Swoboda-Kopec, E. First Report of a Case of Ocular Infection Caused by Purpureocillium lilacinum in Poland. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprute, R.; Salmanton-García, J.; Sal, E.; Malaj, X.; Ráčil, Z.; Ruiz de Alegría Puig, C.; Falces-Romero, I.; Barać, A.; Desoubeaux, G.; Kindo, A.J.; et al. Invasive infections with Purpureocillium lilacinum: Clinical characteristics and outcome of 101 cases from FungiScope® and the literature. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 1593–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monpierre, L.; Ait-Ammar, N.; Valsecchi, I.; Normand, A.C.; Guitard, J.; Riat, A.; Huguenin, A.; Bonnal, C.; Sendid, B.; Hasseine, L.; et al. Species Identification and In Vitro Antifungal Susceptibility of Paecilomyces/Purpureocillium Species Isolated from Clinical Respiratory Samples: A Multicenter Study. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hariprasad, S.M.; Mieler, W.F.; Holz, E.R.; Gao, H.; Kim, J.E.; Chi, J.; Prince, R.A. Determination of vitreous, aqueous, and plasma concentration of OrallyAdministered voriconazole in humans. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2004, 122, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, G.; Pennesi, M.; Shah, K.; Qiao, X.; Hariprasad, S.M.; Mieler, W.F.; Wu, S.M.; Holz, E.R. Safety of intravitreal voriconazole: Electroretinographic and histopathologic studies. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 2003, 101, 183. [Google Scholar]

- Thiel, M.A.; Zinkernagel, A.S.; Burhenne, J.; Kaufmann, C.; Haefeli, W.E. Voriconazole Concentration in Human Aqueous Humor and Plasma during Topical or Combined Topical and Systemic Administration for Fungal Keratitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, W.J.; Egerer, G.; Lellek, H.; Boehme, A.; Greiner, J. Posaconazole after previous antifungal therapy with voriconazole for therapy of invasive aspergillus disease, a retrospective analysis. Mycoses 2013, 56, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.L.; Wang, Y.H.; Ting, S.W.; Sun, P.L. Cutaneous infection caused by Purpureocillium lilacinum: Case reports and literature review of infections by Purpureocillium and Paecilomyces in Taiwan. J. Dermatol. 2023, 50, 1088–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnoldner, M.A.; Kheirkhah, A.; Jakobiec, F.A.; Durand, M.L.; Hamrah, P.J.C. Successful treatment of Paecilomyces lilacinus keratitis with oral posaconazole. Cornea 2014, 33, 747–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.K.; Mekhail, J.T.; Morcos, D.M.; Yang, C.D.; Kedhar, S.R.; Kim, C.; Del Valle Estopinal, M.; Lee, O.L. Three cases of recalcitrant Paecilomyces keratitis in Southern California within a short period. J. Ophthalmic Inflamm. Infect. 2024, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida Oliveira, M.; Carmo, A.; Rosa, A.; Murta, J. Posaconazole in the treatment of refractory Purpureocillium lilacinum (former Paecilomyces lilacinus) keratitis: The salvation when nothing works. BMJ Case Rep. 2019, 12, e228645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa-Moreira, D.; de Lima Neto, R.G.; da Costa, G.L.; de Moraes Borba, C.; Oliveira, M.M.E. Purpureocillium lilacinum an emergent pathogen: Antifungal susceptibility of environmental and clinical strains. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 75, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Prajna, N.V.; Lalitha, P.; Rajaraman, R.; Srinivasan, M.; Arnold, B.F.; Acharya, N.; Lietman, T.; Rose-Nussbaumer, J. Association between in vitro susceptibility and clinical outcomes in fungal keratitis. J. Ophthalmic Inflamm. Infect. 2024, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamoth, F.; Lewis, R.E.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Role and Interpretation of Antifungal Susceptibility Testing for the Management of Invasive Fungal Infections. J. Fungi 2020, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case No. | Age/Sex (Years) | Date (Year/Month) | Risk Factor | Systematic Disease and Immunosuppressed | Time to Diagnosis (Days) | Antifungal Drug | Initial BCVA | Final BCVA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51/M | 2020/12 | Trauma | Tuberculosis | 50 | VCZ, FCZ, NM, AMB | HM | 0.05 |

| 2 | 75/M | 2021/6 | Cataract surgery | None | 60 | VCZ, ITZ, AMB | LP | HM |

| 3 | 71/M | 2021/12 | Pterygium excision | HBP | 45 | VCZ, FCZ | LP | CF |

| 4 | 76/F | 2021/12 | Trauma | HBP | 30 | VCZ, FCZ | HM | HM |

| 5 | 59/F | 2021/12 | Trauma | HBP | 43 | VCZ, FCZ, NM | HM | 0.05 |

| 6 | 67/F | 2022/1 | Trauma | None | 20 | VCZ, FCZ | CF | 0.4 |

| 7 | 59/M | 2022/1 | Trauma | None | 15 | VCZ | CF | 0.075 |

| 8 | 70/M | 2022/2 | Unknown | None | 35 | VCZ, FCZ | HM | HM |

| 9 | 53/F | 2022/2 | Trauma | None | 161 | VCZ, FCZ, AMB | LP | NLP |

| 10 | 65/M | 2022/3 | Unknown | None | 57 | VCZ, FCZ | NLP | NLP |

| 11 | 50/F | 2022/7 | Unknown | Topical and systemic steroids | 180 | VCZ, FCZ, AMB | HM | 0.16 |

| 12 | 64/F | 2022/8 | Trauma | None | 23 | VCZ, FCZ | HM | 0.025 |

| 13 | 34/M | 2022/11 | Unknown | Diabetes, systemic steroids | 31 | VCZ, AMB | CF | HM |

| 14 | 68/M | 2022/12 | Thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy | Systemic steroids | 210 | VCZ, AMB | 0.05 | NLP |

| 15 | 4/M | 2023/1 | Unknown | Topical steroids | 26 | VCZ, AMB | LP | 0.1 |

| 16 | 75/F | 2023/2 | Unknown | None | 67 | VCZ, FCZ, AMB | N/A | N/A |

| 17 | 62/F | 2023/2 | Trauma | None | 67 | VCZ, FCZ | CF | 0.06 |

| 18 | 75/M | 2023/2 | Unknown | HBP | 21 | VCZ | 0.075 | 0.025 |

| 19 | 57/M | 2023/2 | Unknown | HBP, Topical and systemic steroids | 150 | VCZ, AMB | 0.025 | LP |

| 20 | 51/F | 2023/2 | Unknown | None | 38 | VCZ, FCZ, AMB | CF | CF |

| 21 | 46/F | 2023/2 | Unknown | None | 16 | VCZ, FCZ, AMB | LP | HM |

| 22 | 69/M | 2023/3 | Eyelid squamous cell carcinoma surgery | HBP | 66 | N/A | HM | EN |

| 23 | 43/M | 2023/3 | Trauma | None | 132 | VCZ, FCZ, AMB | HM | NLP |

| 24 | 75/F | 2023/3 | Unknown | HBP | 97 | VCZ, FCZ | LP | EN |

| 25 | 59/F | 2023/4 | Unknown | Topical and systemic steroids | 210 | VCZ, AMB | 0.05 | LP |

| 26 | 75/F | 2023/4 | Unknown | None | 186 | VCZ, AMB | NLP | NLP |

| 27 | 72/F | 2023/11 | Trauma | Diabetes | 64 | VCZ | LP | HM |

| 28 | 49/M | 2023/12 | Unknown | None | 24 | VCZ | 0.16 | 0.075 |

| 29 | 62/M | 2024/3 | Trauma | None | 30 | VCZ | HM | CF |

| 30 | 63/F | 2024/4 | Trauma | None | 21 | VCZ, FCZ, AMB | 0.075 | 0.12 |

| 31 | 57/F | 2024/3 | Cataract surgery | HBP, Topical and systemic steroids | 13 | VCZ, TRB | CF | NLP |

| 32 | 58/F | 2024/9 | Unknown | None | 13 | VCZ, NM, AMB | 0.075 | 0.4 |

| 33 | 61/M | 2024/12 | Cataract surgery | Topical and systemic steroids | 54 | VCZ, FCZ | HM | HM |

| 34 | 53/M | 2024/12 | Trauma | Topical steroids | 77 | VCZ, FCZ | 0.05 | HM |

| Initial BCVA (n, %) | Final BCVA (n, %) | |

|---|---|---|

| ≧0.05 | 7 (22.6) | 10 (32.3) |

| >CF − 0.05 | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) |

| CF | 6 (19.4) | 3 (9.7) |

| HM | 9 (29.0) | 8 (25.8) |

| LP | 6 (19.3) | 2 (6.5) |

| NLP | 2 (6.4) | 6 (19.4) |

| Characteristic | Favorable Outcome (n = 15) | Poor Outcome (n = 18) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median year (range) | 59 (4–75) | 63 (34–76) | 0.337 |

| Gender, | 0.732 | ||

| male (%) | 7 (46.7%) | 10 (55.6%) | |

| female (%) | 8 (53.3%) | 8 (44.4%) | |

| Risk factor, no. (%) | 0.339 | ||

| Trauma | 8 (53.3%) | 5 (27.8%) | |

| prior ocular surgery | 1 (6.7%) | 4 (22.2%) | |

| Ocular disease | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.6%) | |

| Unknown | 6 (40.0%) | 8 (44.4%) | |

| Immunosuppressed, no. (%) | 2 (13.3%) | 7 (38.9%) | 0.134 |

| Time to diagnosis, median day (range) | 26 (13–180) | 65 (13–210) | 0.007 |

| Antifungal Drugs (MICs mg/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Voriconazole | Fluconazole | Caspofungin |

| 1 | 0.25 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 2 | 0.5 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 3 | 0.094 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 4 | 0.25 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 5 | 24 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 6 | 0.25 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 7 | 0.38 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 8 | 0.19 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 9 | 0.19 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 10 | 0.094 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 11 | 0.25 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 12 | 0.5 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 13 | 0.064 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 14 | 0.25 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 15 | 0.094 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 16 | 0.19 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 17 | 0.25 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 18 | 0.5 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 19 | 0.25 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 20 | 1 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 21 | 0.125 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 22 | 0.5 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 23 | 0.125 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 24 | 0.094 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 25 | 0.25 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 26 | 0.19 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 27 | 0.25 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 28 | 1 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 29 | 0.5 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 30 | 0.25 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 31 | 0.5 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 32 | 2 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 33 | 2 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

| 34 | 0.5 | ≥256 | ≥32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, X.; Jiang, J.; Huang, H.; Zheng, J.; Zhong, L.; Duan, F. Clinical Manifestations, Antifungal Susceptibilities, and Outcome of Ocular Infections Caused by Purpureocillium lilacinum. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2858. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122858

Zhao X, Jiang J, Huang H, Zheng J, Zhong L, Duan F. Clinical Manifestations, Antifungal Susceptibilities, and Outcome of Ocular Infections Caused by Purpureocillium lilacinum. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2858. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122858

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Xinlei, Jinliang Jiang, Huijing Huang, Jiayi Zheng, Liuxueying Zhong, and Fang Duan. 2025. "Clinical Manifestations, Antifungal Susceptibilities, and Outcome of Ocular Infections Caused by Purpureocillium lilacinum" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2858. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122858

APA StyleZhao, X., Jiang, J., Huang, H., Zheng, J., Zhong, L., & Duan, F. (2025). Clinical Manifestations, Antifungal Susceptibilities, and Outcome of Ocular Infections Caused by Purpureocillium lilacinum. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2858. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122858