Toxicity of 6:2 Chlorinated Polyfluorinated Ether Sulfonate (F-53B) to Escherichia coli: Growth Inhibition, Morphological Disruption, Oxidative Stress, and DNA Damage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain, Chemicals, and Reagents

2.2. Bacterial Toxicity Assessment

2.3. SEM Analysis

2.4. Measurement of Cell Surface Hydrophobicity

2.5. Measurement of Membrane Permeability

2.6. ATR-FTIR Analysis

2.7. Determination of Oxidative Stress

2.8. Alkaline Comet Assay

2.9. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

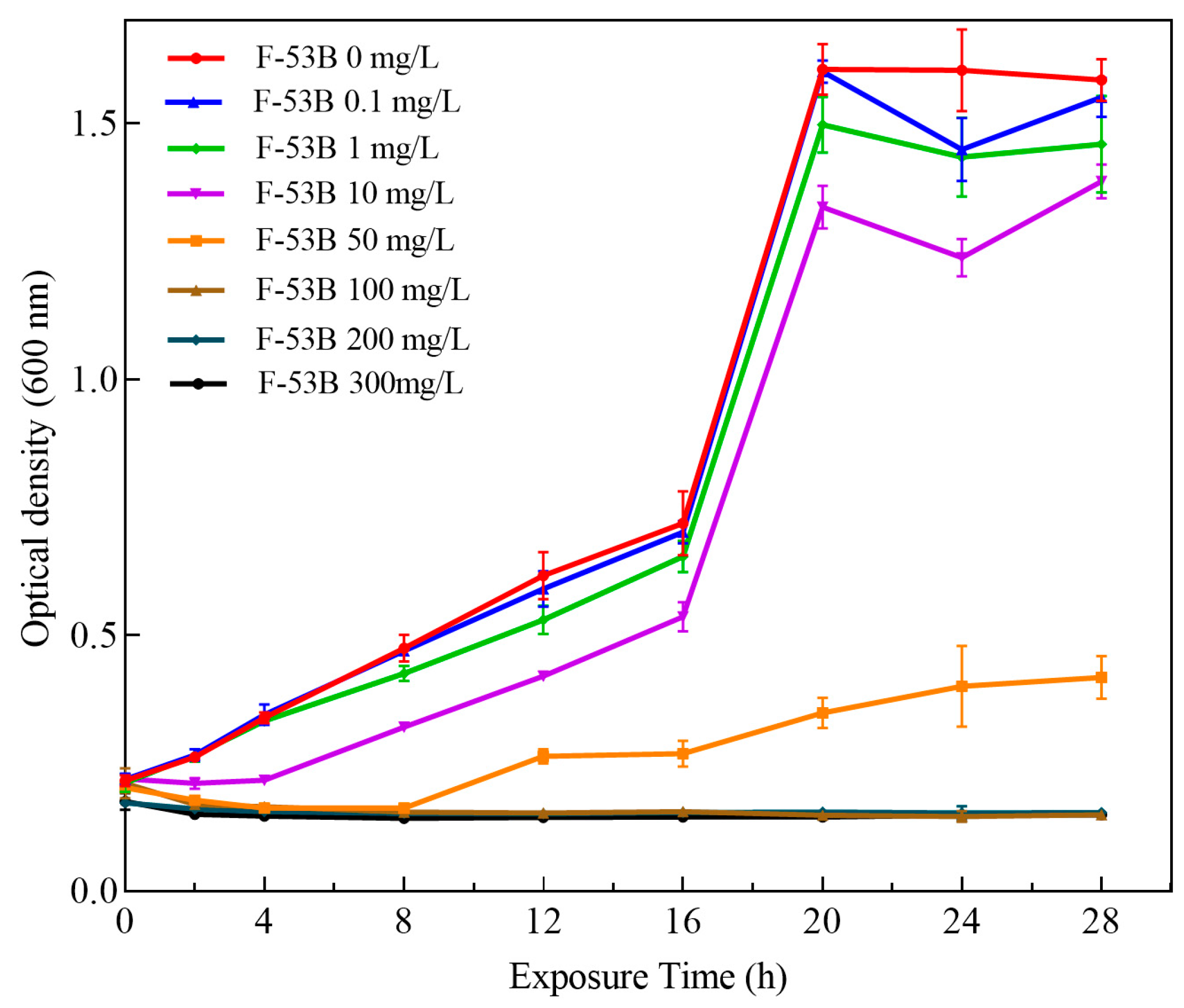

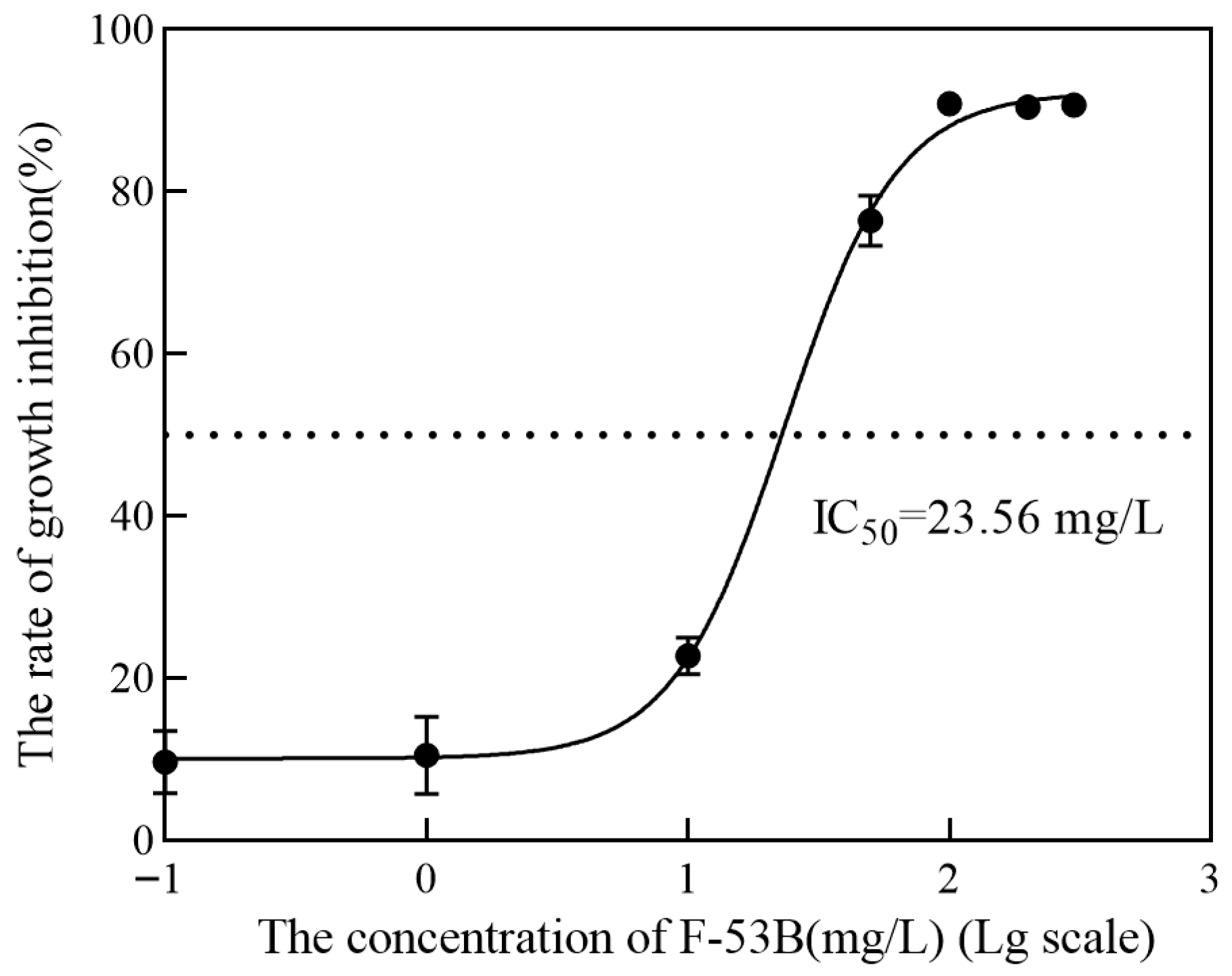

3.1. Effect of F-53B on the Growth Profile

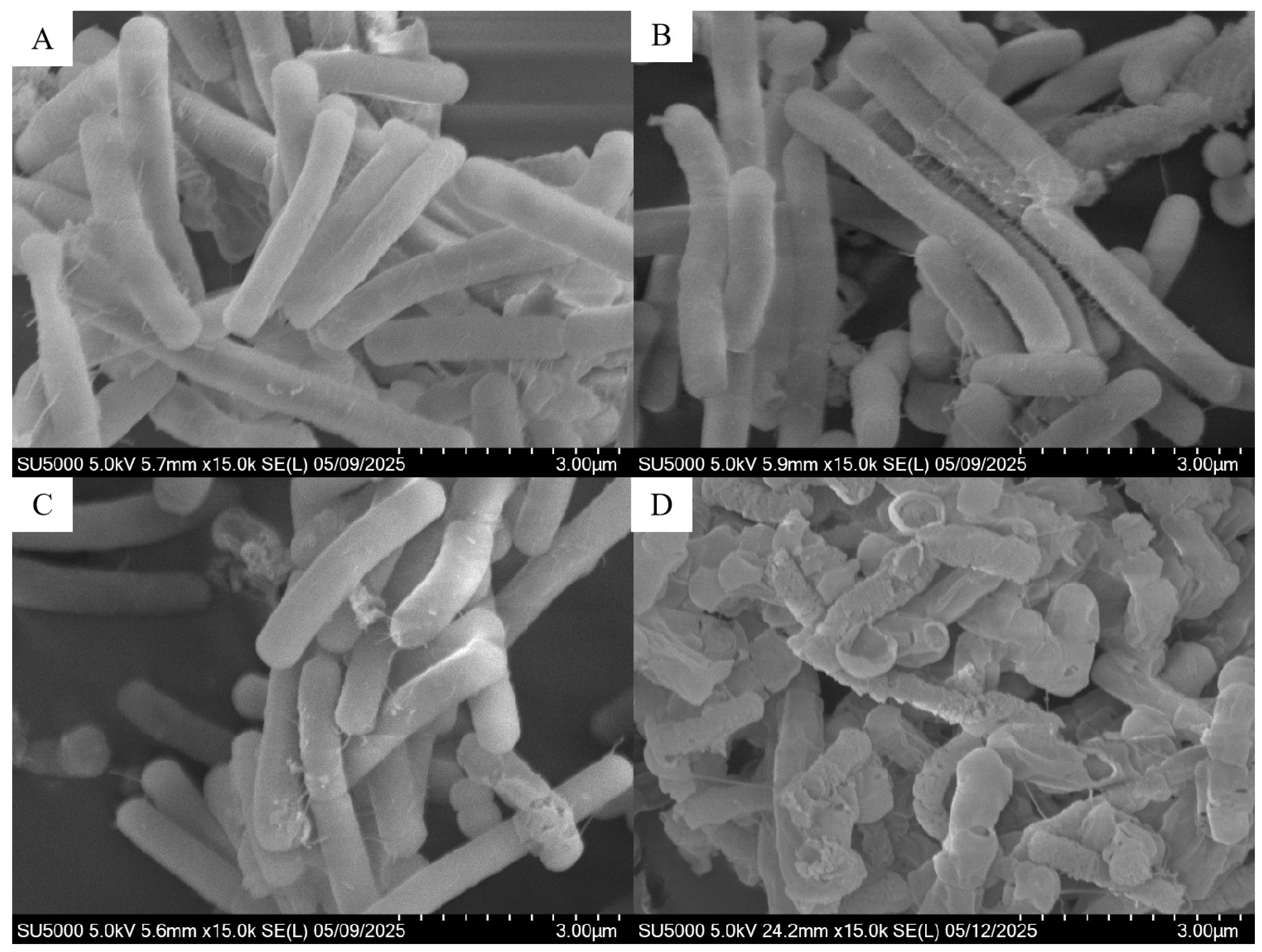

3.2. Effect of F-53B on Cellular Morphology

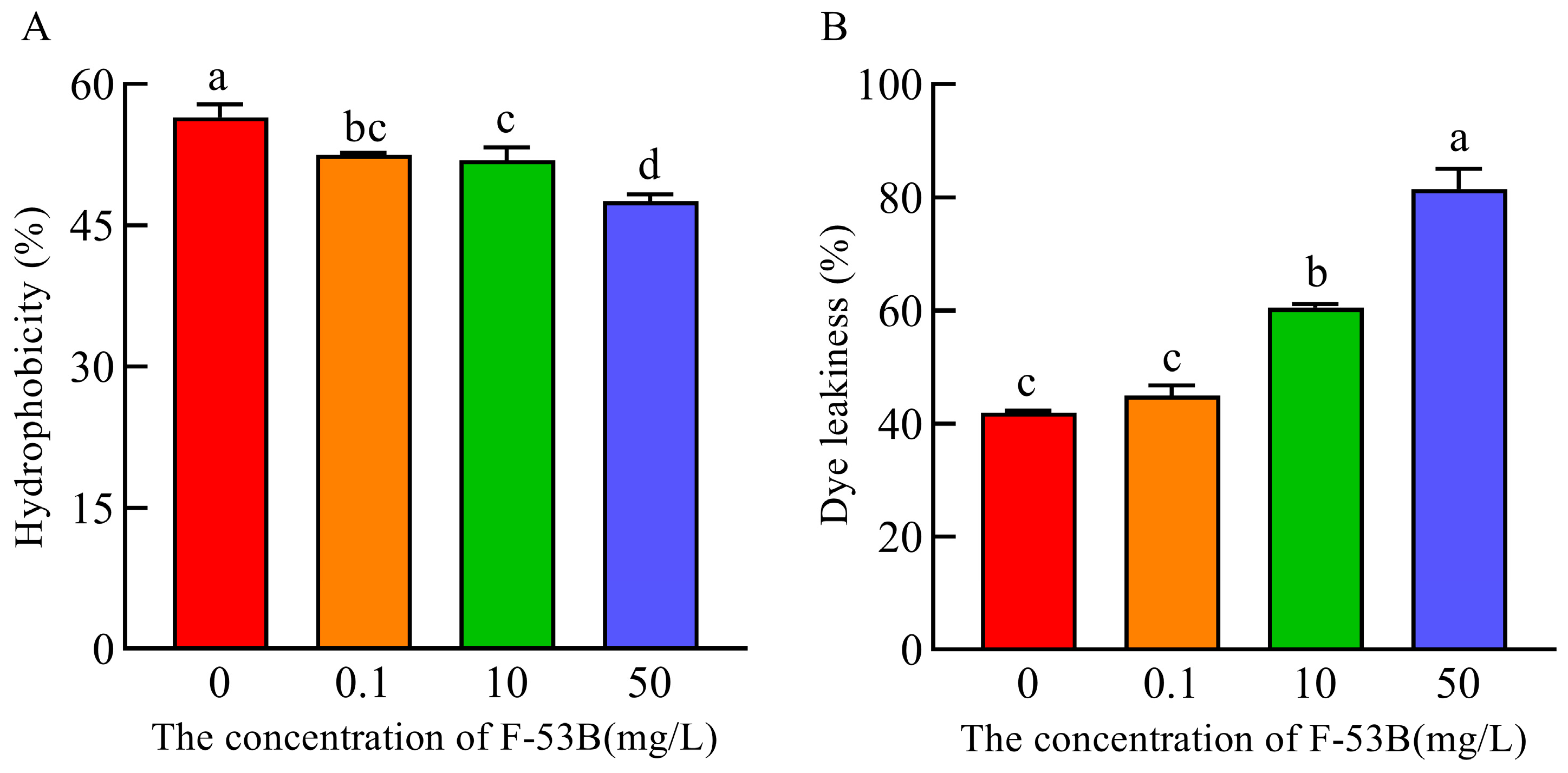

3.3. Effect of F-53B on Cell Surface Properties

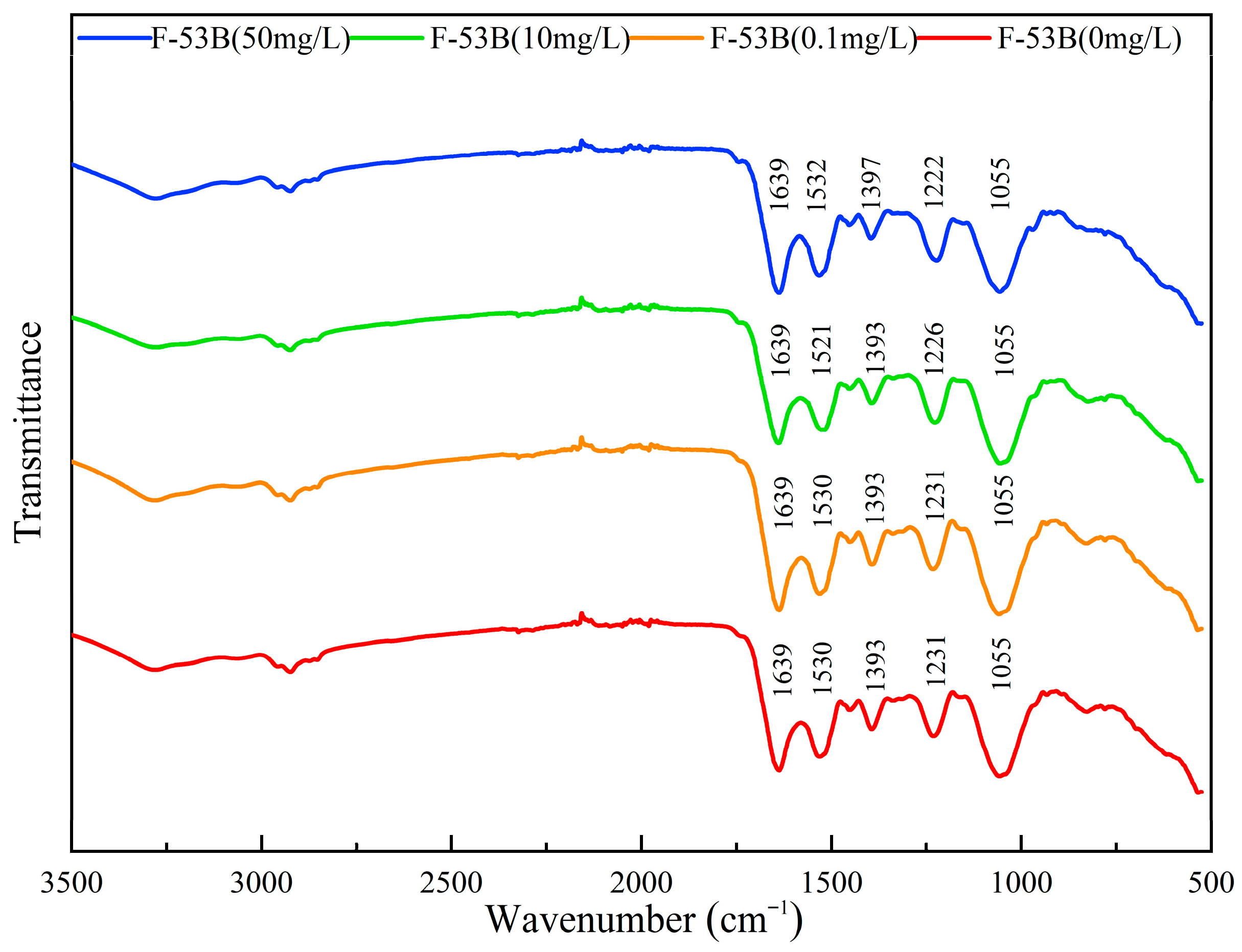

3.4. Effect of F-53B on Chemical Structures and Functional Groups

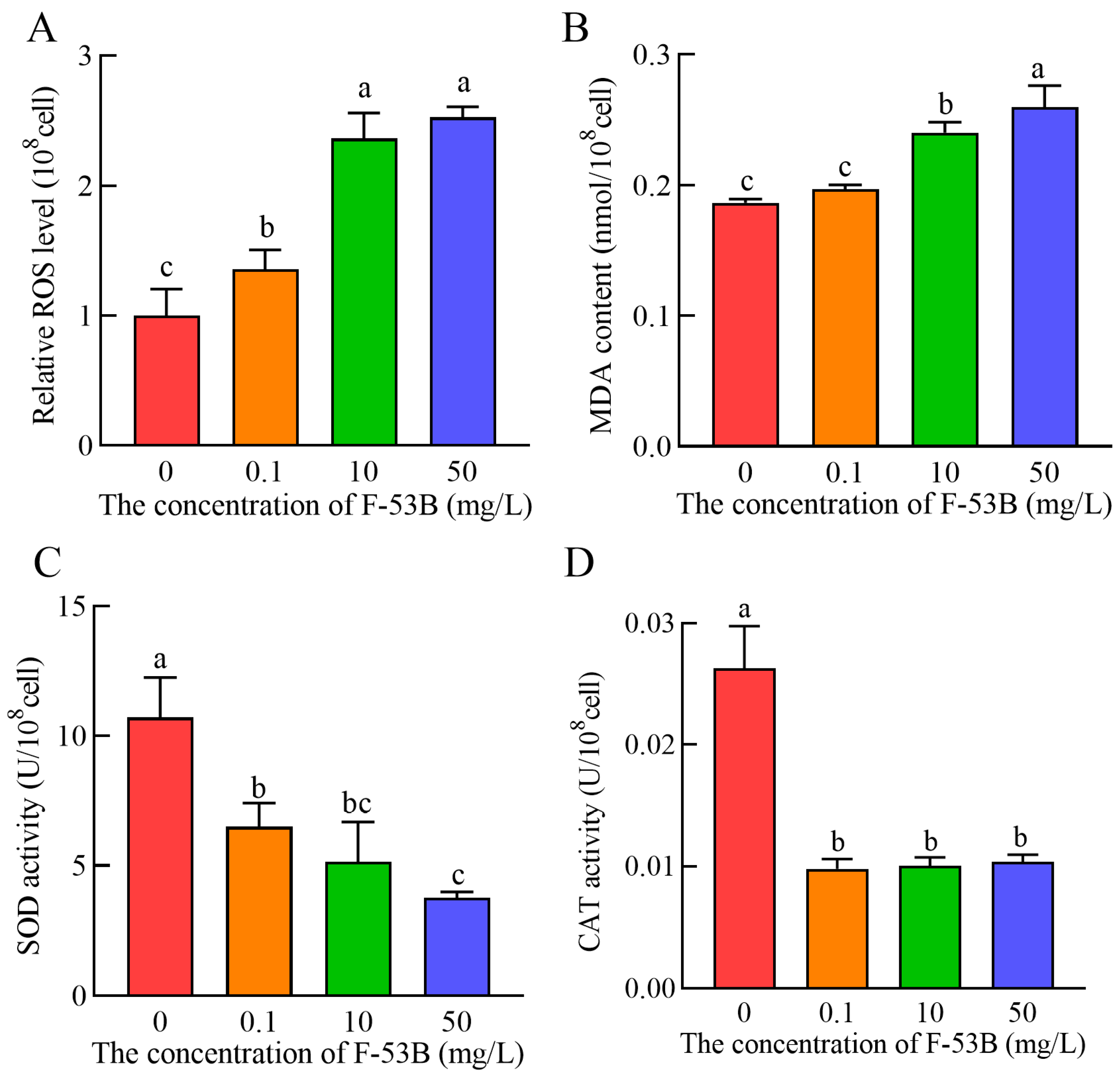

3.5. Effect of F-53B on Oxidative Stress

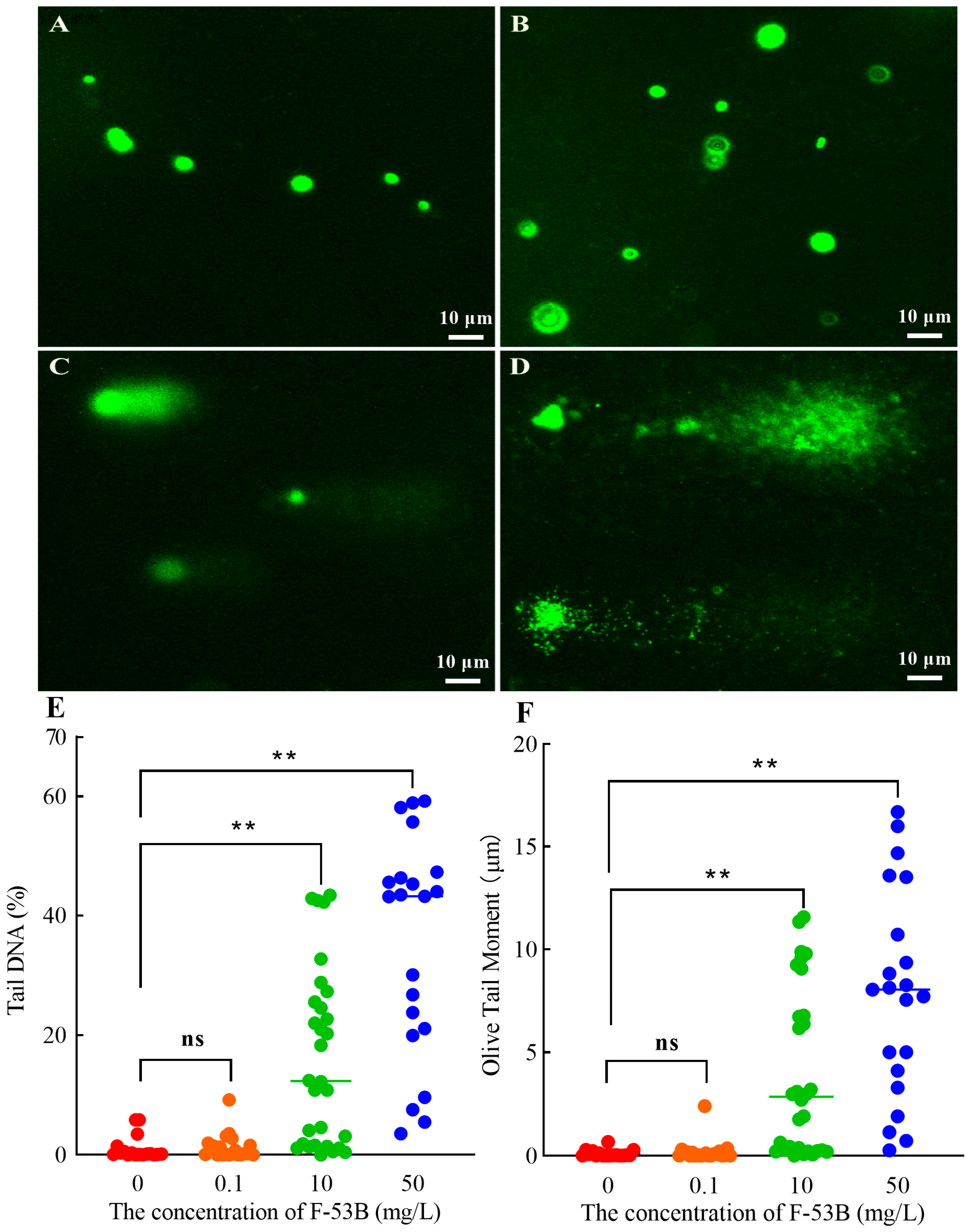

3.6. DNA Damage Induced by F-53B

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| F-53B | 6:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate |

| PFOS | Perfluorooctane sulfonate |

| IC50 | The half maximal growth inhibition concentration |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| PFASs | Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances |

| POPs | Persistent organic pollutants |

| PFOA | Perfluorooctanoic acid |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| OD600 | Optical density at 600 nm |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| CSH | Cell surface hydrophobicity |

| MATH | Microbial adhesion to hydrocarbons |

| ART-FTIR | Attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| DCFH-DA | Fluorescent probe 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate |

| FI | Fluorescent intensity |

| TDNA | Tail DNA% |

| OTM | Olive tail moment |

| MIC | The minimum inhibitory concentration |

| (O2−•) | Superoxide anions |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

References

- Brunn, H.; Arnold, G.; Körner, W.; Rippen, G.; Steinhäuser, K.G.; Valentin, I. PFAS: Forever chemicals-persistent, bioaccumulative and mobile. Reviewing the status and the need for their phase out and remediation of contaminated sites. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, T.Y.; Kwak, I.S. Current understanding of human bioaccumulation patterns and health effects of exposure to perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 487, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.X.; Huang, J.; Cagnetta, G.; Yu, G. Removal of F-538 as PFOS alternative in chrome plating wastewater by UV/Sulfite reduction. Water Res. 2019, 163, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.J.; Liu, J.L.; Bao, K.; Chen, N.N.; Meng, B. Multicompartment occurrence and partitioning of alternative and legacy per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in an impacted river in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyn, M.; Lee, H.; Curry, J.; Tu, W.Q.; Ekker, M.; Mennigen, J.A. Effects of PFOS, F-53B and OBS on locomotor behaviour, the dopaminergic system and mitochondrial function in developing zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Pollut. 2023, 326, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, Z.; Guo, X.T.; Li, Y.; Wu, Z.H.; Zhu, L.Y. Evidences for replacing legacy per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances with emerging ones in Fen and Wei River basins in central and western China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 377, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.W.; Huang, J.; Yang, Y.; Hui, Y.M.; Ge, Y.X.; Larssen, T.; Yu, G.; Deng, S.B.; Wang, B.; Harman, C. First report of a Chinese PFOS alternative overlooked for 30 years: Its toxicity, persistence, and presence in the environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 10163–10170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F.; Zhao, Y.M.; Li, F.; Li, Z.L.; Liang, J.P.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, M. Impact of the novel chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate, F-53B, on gill structure and reproductive toxicity in zebrafish. Aquat. Toxicol. 2024, 275, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ti, B.W.; Li, L.; Liu, J.G.; Chen, C.K. Global distribution potential and regional environmental risk of F-53B. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 640, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.L.; Vestergren, R.; Xu, L.; Zhou, Z.; Li, C.X.; Liang, Y.; Cai, Y.Q. Human exposure and elimination kinetics of chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonic acids (Cl-PFESAs). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 2396–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, G.H.; Guo, H.; Sheng, N.; Cui, Q.Q.; Pan, Y.T.; Wang, J.X.; Guo, Y.; Dai, J.Y. Two-generational reproductive toxicity assessment of 6:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate (F-53B, a novel alternative to perfluorooctane sulfonate) in zebrafish. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243, 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.H.; Cui, Q.Q.; Pan, Y.T.; Sheng, N.; Sun, S.J.; Guo, Y.; Dai, J.Y. 6:2 Chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate, a PFOS alternative, induces embryotoxicity and disrupts cardiac development in zebrafish embryos. Aquat. Toxicol. 2017, 185, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Y.; Zeeshan, M.; Dang, Y.; Liang, L.Y.; Gong, Y.C.; Li, Q.Q.; Tan, Y.W.; Fan, Y.Y.; Lin, L.Z.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Environmentally relevant concentrations of F-53B induce eye development disorders-mediated locomotor behavior in zebrafish larvae. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.H.; Cui, Q.Q.; Wang, J.X.; Guo, H.; Pan, Y.T.; Sheng, N.; Guo, Y.; Dai, J.Y. Chronic exposure to 6:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate acid (F-53B) induced hepatotoxic effects in adult zebrafish and disrupted the PPAR signaling pathway in their offspring. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 249, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Wu, Y.M.; Xu, C.; Jin, Y.X.; He, X.L.; Wan, J.B.; Yu, X.L.; Rao, H.M.; Tu, W.Q. Multiple approaches to assess the effects of F-53B, a Chinese PFOS alternative, on thyroid endocrine disruption at environmentally relevant concentrations. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.M.; Deng, M.; Jin, Y.X.; Mu, X.Y.; He, X.L.; Luu, N.T.; Yang, C.Y.; Tu, W.Q. Uptake and elimination of emerging polyfluoroalkyl substance F-53B in zebrafish larvae: Response of oxidative stress biomarkers. Chemosphere 2019, 215, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.J.; Wang, J.S.; Sheng, N.; Cui, R.N.; Deng, Y.Q.; Dai, J.Y. Subchronic reproductive effects of 6:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate (6:2 Cl-PFAES), an alternative to PFOS, on adult male mice. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 358, 256–264, Erratum in J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 365, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.P.; Wu, L.Y.; Zeng, H.X.; Zhang, J.; Qin, S.J.; Liang, L.X.; Andersson, J.; Meng, W.J.; Chen, X.Y.; Wu, Q.Z.; et al. Hepatic injury and ileitis associated with gut microbiota dysbiosis in mice upon F-53B exposure. Environ. Res. 2024, 248, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Feng, Y.Y.; Zhang, R.Y.; Xu, H.Y.; Fu, F. 6:2 chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonate (F-53B) induced nephrotoxicity associated with oxidative stress, inflammation and fibrosis in mice. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2025, 405, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.Z.; Lv, J.L.; Li, H.R.; An, Z.W.; Li, L.F.; Ke, Y.J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.H.; Wang, L.; Li, A.; et al. Angiotoxic effects of chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate, a novel perfluorooctane sulfonate substitute, in vivo and in vitro. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.H.; Lang, Y.Y.; Feng, Y.Y.; Tang, X.M.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Xu, H.Y.; Liu, Y. Maternal F-53B exposure during pregnancy and lactation affects bone growth and development in male offspring. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 279, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.H.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.L.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.Y.; Sun, H.W.; Zhang, L.Y. Comparative toxicological effects of perfluorooctane sulfonate and its alternative 6:2 chlorinated polyfluorinated ether sulfonate on earthworms. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2024, 43, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kost, C.; Patil, K.R.; Friedman, J.; Garcia, S.L.; Ralser, M. Metabolic exchanges are ubiquitous in natural microbial communities. Nat. Microbiol. 2023, 8, 2244–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Geisler, M.; Zhang, W.L.; Liang, Y.N. Fluoroalkylether compounds affect microbial community structures and abundance of nitrogen cycle-related genes in soil-microbe-plant systems. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 228, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobels, I.; Dardenne, F.; De Coen, W.; Blust, R. Application of a multiple endpoint bacterial reporter assay to evaluate toxicological relevant endpoints of perfluorinated compounds with different functional groups and varying chain length. Toxicol. Vitro 2010, 24, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, N.J.M.; Simcik, M.F.; Novak, P.J. Perfluoroalkyl substances increase the membrane permeability and quorum sensing response in Aliivibrio fischeri. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2018, 5, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, T.T.; Yuan, D.; Gao, C.Z.; Liu, C.G. Probing the single and combined toxicity of PFOS and Cr(VI) to soil bacteria and the interaction mechanisms. Chemosphere 2020, 249, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.S.; Zhang, S.; Yang, K.; Zhu, L.Z.; Lin, D.H. Toxicity of perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoic acid to Escherichia coli: Membrane disruption, oxidative stress, and DNA damage induced cell inactivation and/or death. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 214, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieke, A.S.C.; Pillai, S.D. Escherichia coli cells exposed to lethal doses of electron beam irradiation retain their ability to propagate bacteriophages and are metabolically active. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espigares, M.; Roman, I.; Alonso, J.M.G.; Deluis, B.; Yeste, F.; Galvez, R. Proposal and application of an ecotoxicity biotest based on Escherichia coli. J. Appl. Toxicol. 1990, 10, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.; Gellert, G.; Ludwig, J.; Lichtenberg-Fraté, H. Phenotypic yeast growth analysis for chronic toxicity testing. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2004, 59, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.T.; Li, J.; Liu, C.G. Improvement of α-amylase to the metabolism adaptions of soil bacteria against PFOS exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Lim, J.W.; Kim, H. α-Lipoic acid inhibits apoptosis by suppressing the loss of ku proteins in Helicobacter pylori-infected human gastric epithelial cells. Nutrients 2022, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, X.; Li, M. Combined toxic effects of polystyrene microplastics and cadmium on earthworms. Asian J. Ecotoxicol. 2022, 17, 216–226. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.D.; Sivakumaran, K. Individual and combined toxic effect of nickel and chromium on biochemical constituents in E. coli using FTIR spectroscopy and principle component analysis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 130, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.J.; Liu, Z.X.; Wang, Y.D.; Li, X.L.; Hu, J.; Lü, J.H. Synchrotron FTIR spectroscopy reveals molecular changes in Escherichia coli upon Cu2+ exposure. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 2016, 27, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, N.; Cui, R.N.; Wang, J.H.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.S.; Dai, J.Y. Cytotoxicity of novel fluorinated alternatives to long-chain perfluoroalkyl substances to human liver cell line and their binding capacity to human liver fatty acid binding protein. Arch. Toxicol. 2018, 92, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Yan, X.; He, M.; Wang, Y.; Kang, T.; Cai, F.; Zheng, J.; Xie, C. Cytotoxic effects of F-53B on human hepatoma cells HepG2 and Hep3B. Asian J. Ecotoxicol. 2024, 19, 232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.Y.; Yi, J.F.; Lai, H.; Sun, L.W.; Mennigen, J.A.; Tu, W.Q. Concentration-dependent toxicokinetics of novel PFOS alternatives and their chronic combined toxicity in adult zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 839, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.L.; Vestergren, R.; Zhou, Z.; Song, X.W.; Xu, L.; Liang, Y.; Cai, Y.Q. Tissue distribution and whole body burden of the chlorinated polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonic acid F-53B in Crucian Carp (Carassius carassius): Evidence for a highly bioaccumulative contaminant of emerging concern. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 14156–14165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, H.F.; Wang, D.; Xue, Y.X.; Zhang, Z.; Niu, J.J.; Hong, Y.Z.; Drlica, K.; Zhao, X.L. Dimethyl sulfoxide protects Escherichia coli from rapid antimicrobial-mediated killing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 5054–5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; Ismail, S.; Ahmad, H.A.; Awad, H.M.; Tawfik, A.; Ni, S.Q. Dosage-dependent toxicity of universal solvent dimethyl sulfoxide to the partial nitrification wastewater treatment process. ACS EST Water 2023, 3, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyberghs, J.; Bars, C.; Ayuso, M.; Van, G.C.; Foubert, K.; Van, C.S. DMSO Concentrations up to 1% are Safe to be used in the zebrafish embryo developmental toxicity assay. Front. Toxicol. 2021, 3, 804033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, T.; Lin, Y.F.; Wang, T.; Liu, R.Z.; Jiang, G.B. Identification of novel polyfluorinated ether sulfonates as PFOS alternatives in municipal sewage sludge in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 6519–6527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.; Yang, M.; Ye, J.; Qin, H. Cytotoxicity of pentadecafluorooctanoic acid on Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae 2016, 36, 1486–1492. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, A.; Serra, D.; Prieto, C.; Schmitt, J.; Naumann, D.; Yantorno, O. Characterization of Bordetella pertussis growing as biofilm by chemical analysis and FT-IR spectroscopy. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 71, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portune, K.J.; Cary, S.C.; Warner, M.E. Antioxidant enzyme response and reactive oxygen species production in marine raphidophytes. J. Phycol. 2010, 46, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.B.; Xu, C.; Song, J.Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Teng, C.L.; Ma, K.; Xie, F. Toxicokinetic and liver proteomic study of the Chinese rare minnow (Gobiocypris rarus) exposed to F-53B. Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 282, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.M.; Huang, J.; Deng, M.; Jin, Y.X.; Yang, H.L.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Q.Y.; Mennigen, J.A.; Tu, W.Q. Acute exposure to environmentally relevant concentrations of Chinese PFOS alternative F-53B induces oxidative stress in early developing zebrafish. Chemosphere 2019, 235, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valavanidis, A.; Vlahogianni, T.; Dassenakis, M.; Scoullos, M. Molecular biomarkers of oxidative stress in aquatic organisms in relation to toxic environmental pollutants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2006, 64, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, A.F.; Peng, C.; Ng, J.C. Genotoxicity assessment of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances mixtures in human liver cells (HepG2). Toxicology 2022, 482, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Chang, V.W.C.; Gin, K.Y.H.; Nguyen, V.T. Genotoxicity of perfluorinated chemicals (PFCs) to the green mussel (Perna viridis). Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 487, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.M.; Li, C.D.; Wen, Y.Z.; Liu, W.P. Antioxidant defense system responses and DNA damage of earthworms exposed to Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). Environ. Pollut. 2013, 174, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.K.; Lee, S.K.; Jung, J. Integrated assessment of biomarker responses in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) exposed to perfluorinated organic compounds. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 180, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, A.; Eke, D.; Ekinci, S.Y.; Yildirim, S. The protective role of curcumin on perfluorooctane sulfonate-induced genotoxicity: Single cell gel electrophoresis and micronucleus test. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Gao, M.; Cao, T.; Wang, J.; Luo, M.; Liu, S.; Zeng, X.; Huang, J. PFOS and F-53B disrupted inner cell mass development in mouse preimplantation embryo. Chemosphere 2024, 349, 140948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crebelli, R.; Caiola, S.; Conti, L.; Cordelli, E.; De Luca, G.; Dellatte, E.; Eleuteri, P.; Iacovella, N.; Leopardi, P.; Marcon, F.; et al. Can sustained exposure to PFAS trigger a genotoxic response? A comprehensive genotoxicity assessment in mice after subacute oral administration of PFOA and PFBA. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 106, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, M.S.; Evans, M.D.; Dizdaroglu, M.; Lunec, J. Oxidative DNA damage: Mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Z.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X. Purification and characterization of superoxide dismutases from sea buckthorn and chestnut rose. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, G.; Pandey, S.; Ray, A.K.; Kumar, R. Bioremediation of heavy metals by a novel bacterial strain enterobacter cloacae and its antioxidant enzyme activity, flocculant production, and protein expression in presence of lead, cadmium, and nickel. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2015, 226, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.X.; Tang, Y.; Han, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, C.; Hu, Y.; Lu, R.; Wang, F.; Shi, W.; et al. Immunotoxicity of pentachlorophenol to a marine bivalve species and potential toxification mechanisms underpinning. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 439, 129681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di, J.; Li, Z.; Yuan, L.; Liu, J.; Chai, B. Toxicity of 6:2 Chlorinated Polyfluorinated Ether Sulfonate (F-53B) to Escherichia coli: Growth Inhibition, Morphological Disruption, Oxidative Stress, and DNA Damage. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2819. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122819

Di J, Li Z, Yuan L, Liu J, Chai B. Toxicity of 6:2 Chlorinated Polyfluorinated Ether Sulfonate (F-53B) to Escherichia coli: Growth Inhibition, Morphological Disruption, Oxidative Stress, and DNA Damage. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2819. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122819

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi, Jun, Zinian Li, Lixia Yuan, Jinxian Liu, and Baofeng Chai. 2025. "Toxicity of 6:2 Chlorinated Polyfluorinated Ether Sulfonate (F-53B) to Escherichia coli: Growth Inhibition, Morphological Disruption, Oxidative Stress, and DNA Damage" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2819. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122819

APA StyleDi, J., Li, Z., Yuan, L., Liu, J., & Chai, B. (2025). Toxicity of 6:2 Chlorinated Polyfluorinated Ether Sulfonate (F-53B) to Escherichia coli: Growth Inhibition, Morphological Disruption, Oxidative Stress, and DNA Damage. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2819. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122819