Recombinant Forms of α-Amylase AmyBL159 from a Thermophilic Bacterium Bacillus licheniformis MGMM159: The Effect of the Expression System on the Enzyme Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Identification of Bacterial Strain

2.2. Bacterial Strains, Vectors and Recombinant Plasmids

2.3. Creating of Recombinant Plasmids

2.4. Heterologous Expression of the α-Amylase Gene in Cells of E. coli and B. subtillis

2.5. Purification of the Recombinant Protein from the Culture Supernatant

2.6. Activity Assay of α-Amylase

2.7. Determining the Effect of Temperature, pH, Metal Ions, and Inhibitors on Amylase Activity

2.8. Determination of Amylase Thermostability

2.9. Obtaining a 3D-Model of the α-Amylase from B. licheniformis MGMM159 and Its Structural Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

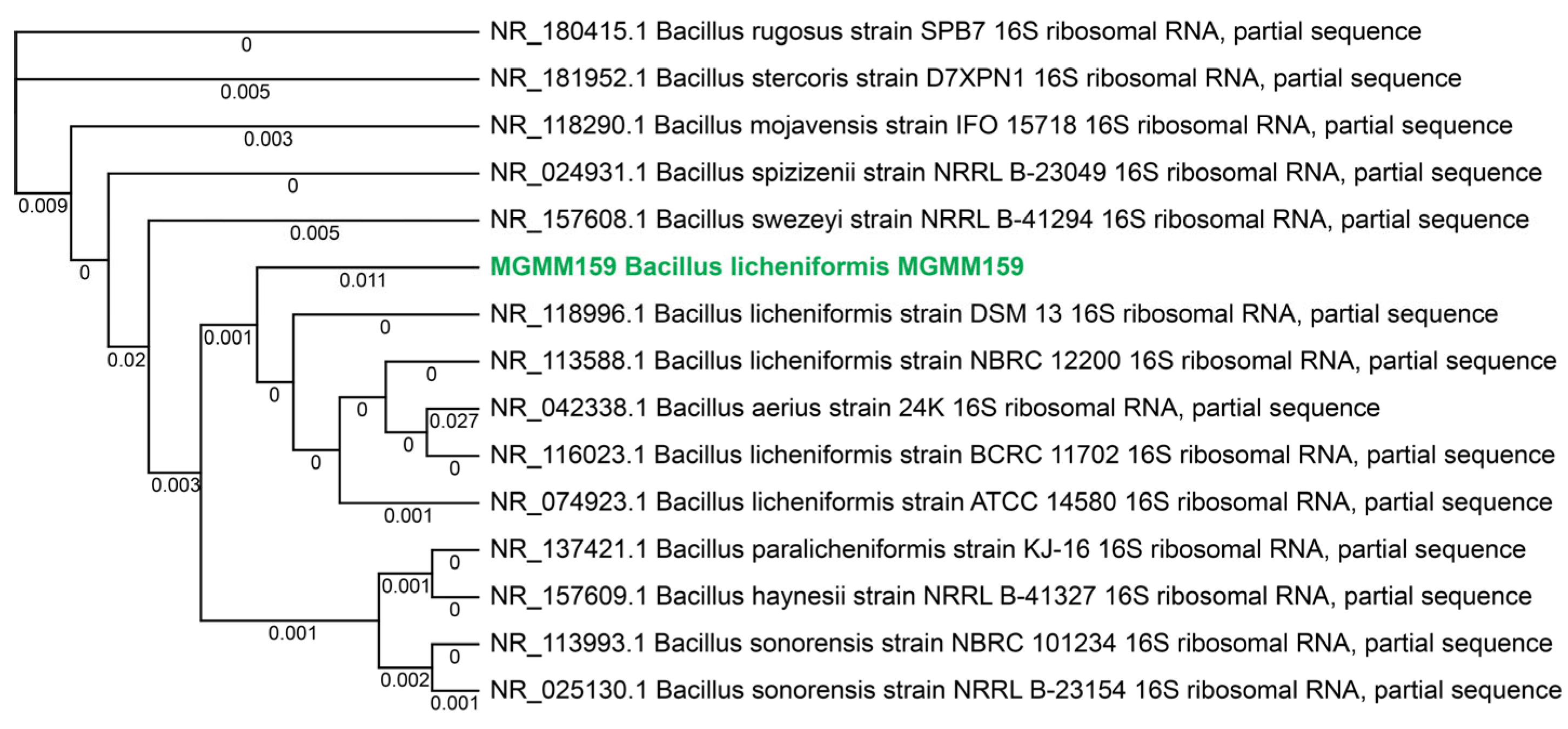

3.1. Bacterial Strain Identification

3.2. Cloning of the α-Amylase Gene from B. licheniformis MGMM159

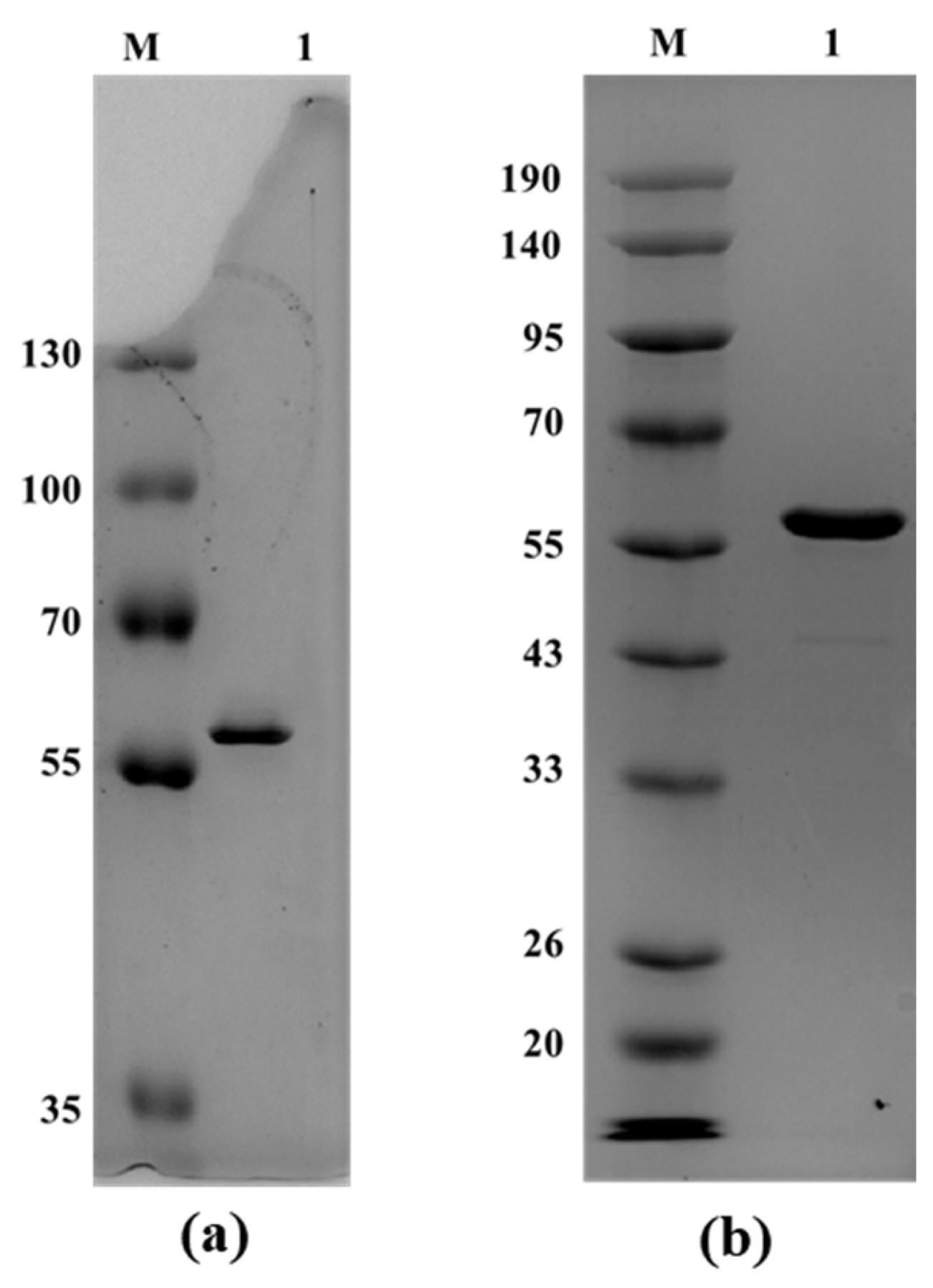

3.3. Heterologous Expression and Purification of the Secreted Protein

3.4. Temperature Optimum of Activity and Thermostability of Recombinant α-Amylases

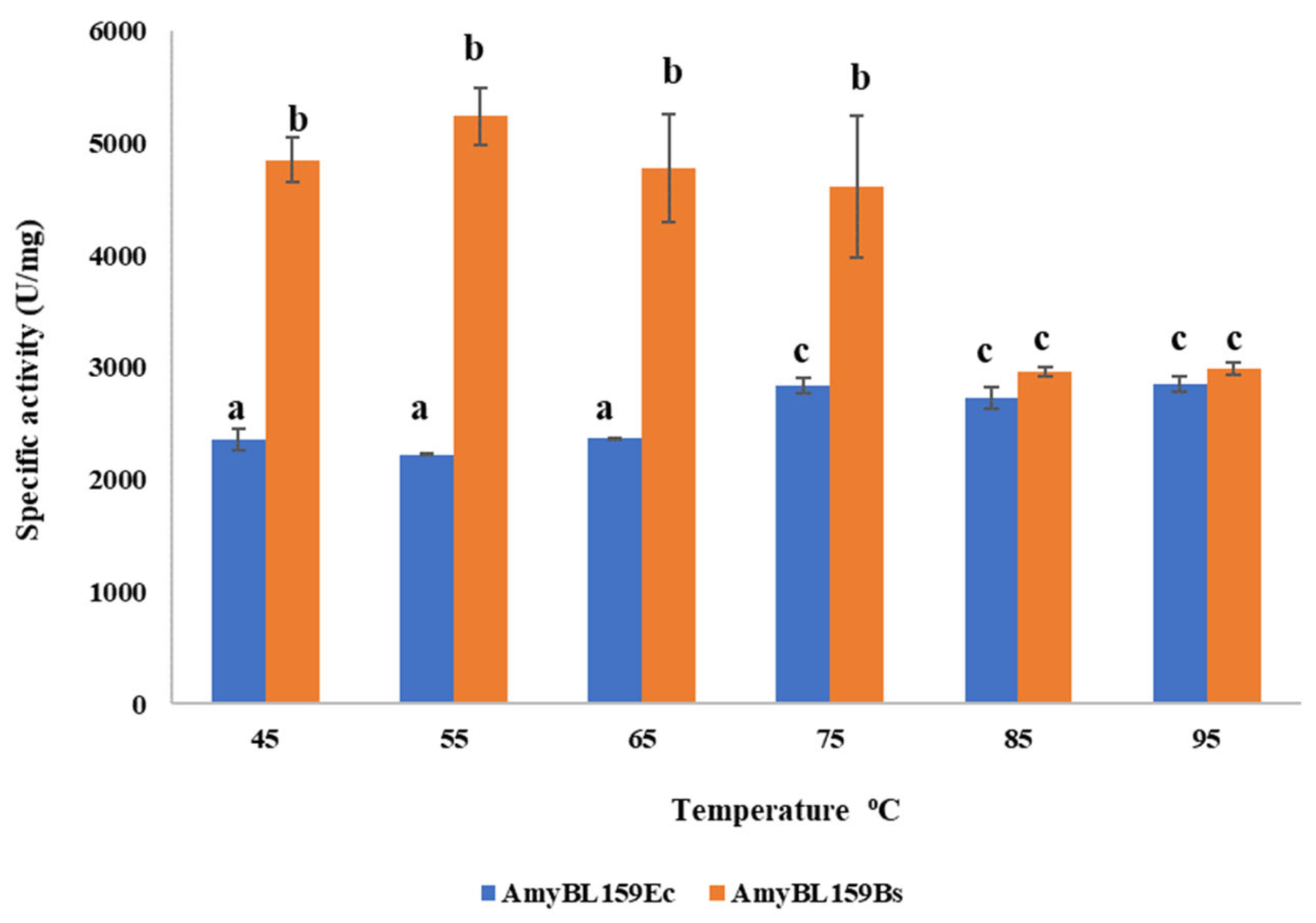

3.4.1. Determination of the Reaction Temperature Optimum

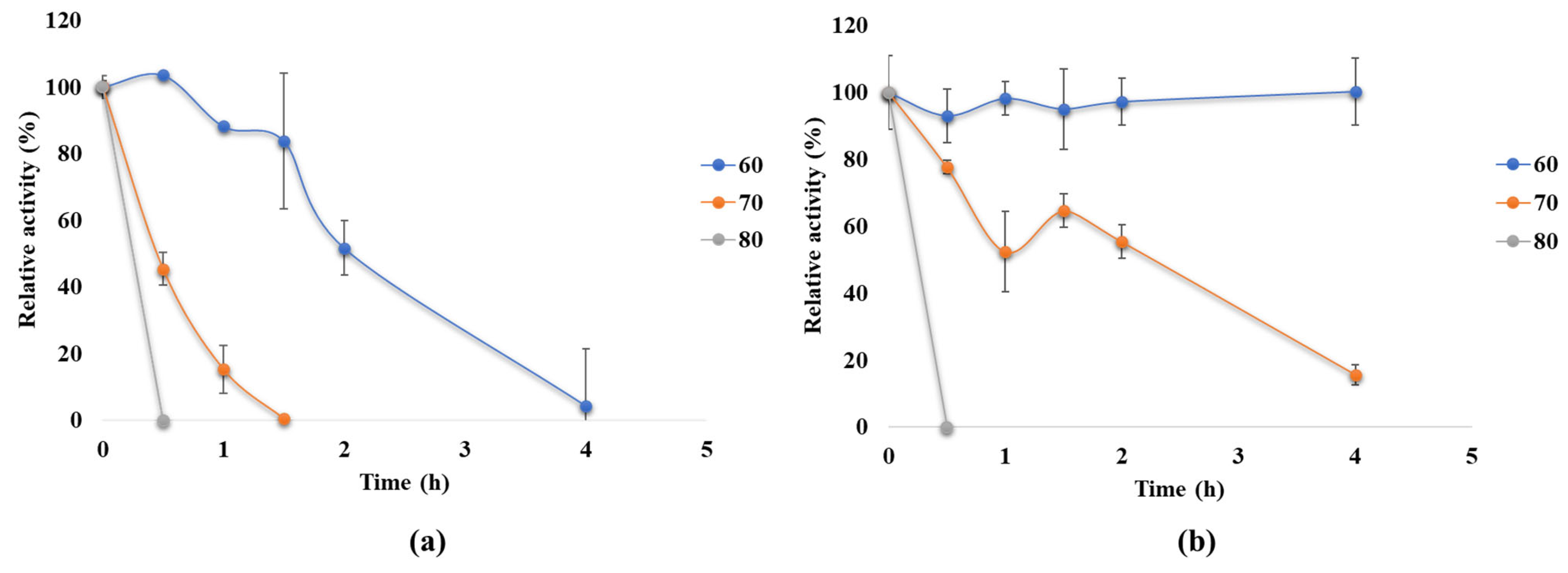

3.4.2. Thermostability of the Recombinant α-Amylase

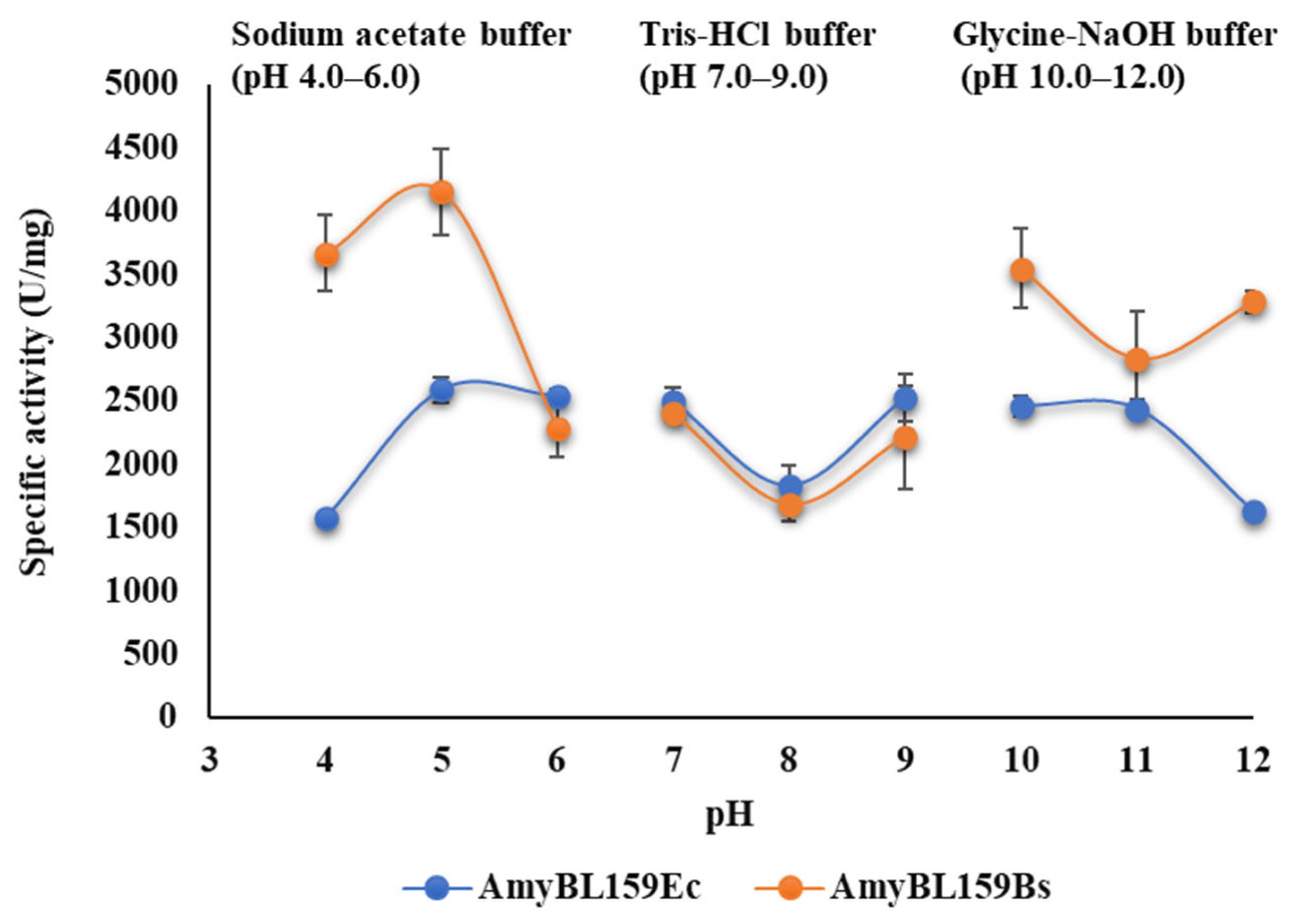

3.5. pH Optimum of Recombinant α-Amylase Forms from B. licheniformis MGMM159

3.6. Analysis of the Influence of Metal Cations, Chelating Agent, and Detergent on α-Amylase Activity

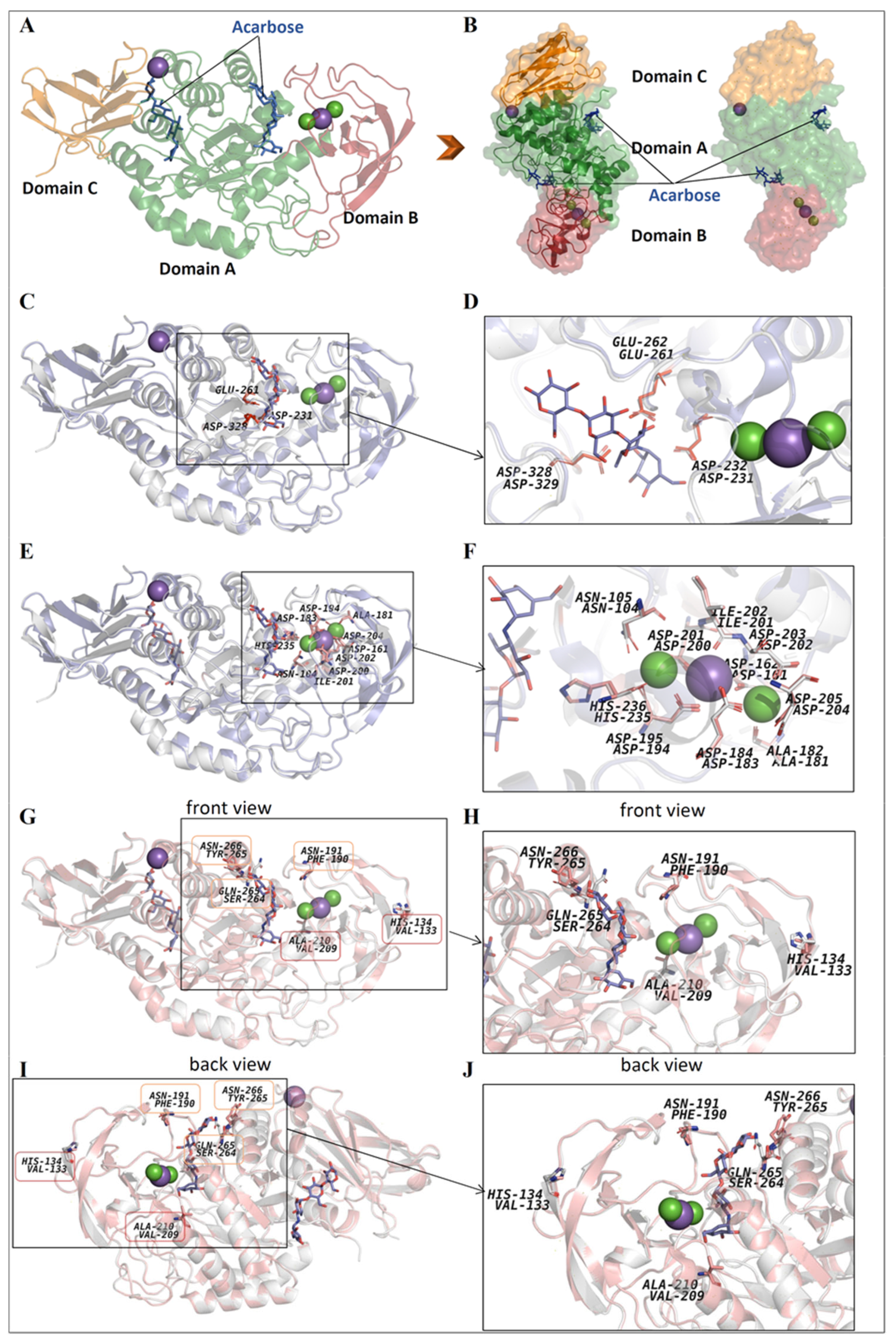

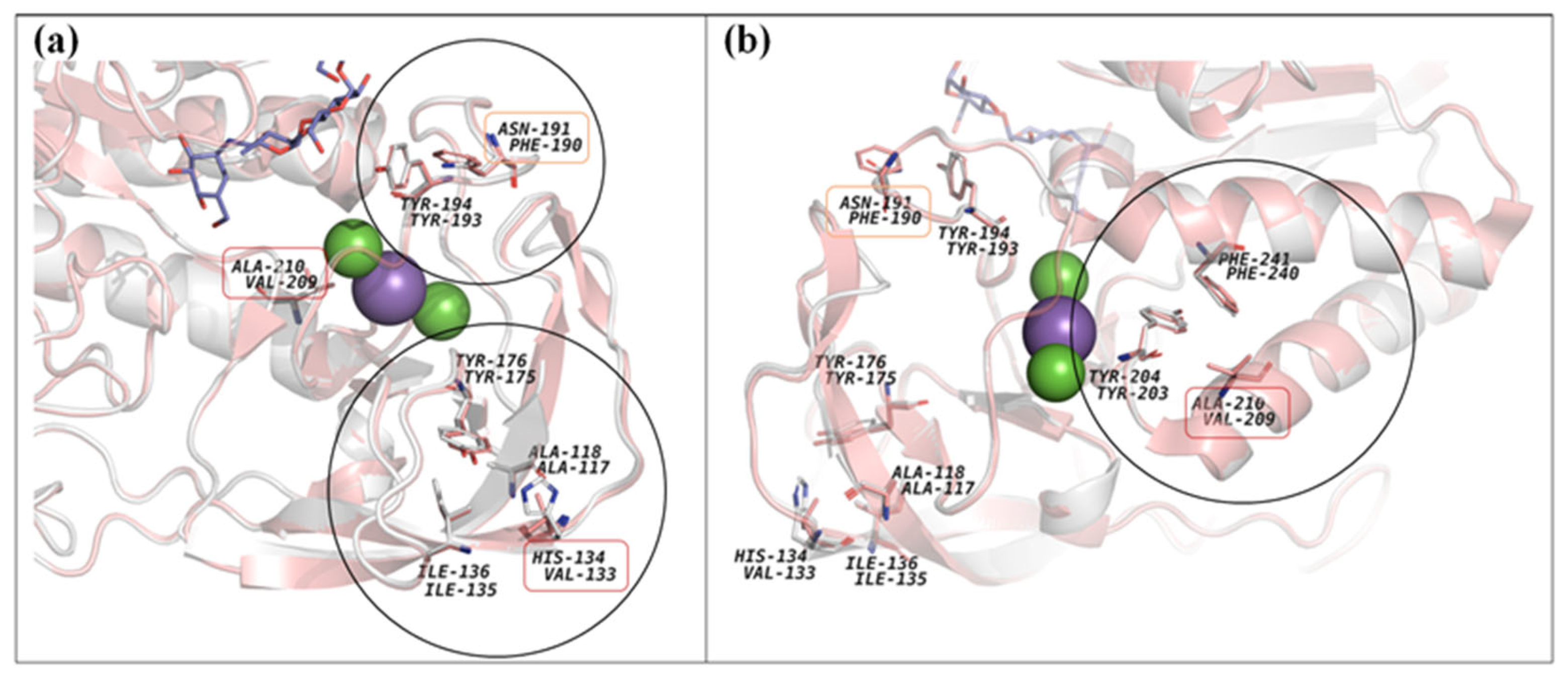

3.7. 3D-Model and Structural Properties of the α-Amylase AmyBL159

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Omemu, A.M.; Akpan, I.; Bankole, M.O.; Teniola, O.D. Hydrolysis of Raw Tuber Starches by Amylase of Aspergillus Niger AM07 Isolated from the Soil. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2005, 4, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Salinas, A.; Rodríguez-Delgado, M.; Gómez-Treviño, J.; López-Chuken, U.; Olvera-Carranza, C.; Blanco-Gámez, E.A. Novel Thermotolerant Amylase from Bacillus Licheniformis Strain LB04: Purification, Characterization and Agar-Agarose. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivaramakrishnan, S.; Gangadharan, D.; Nampoothiri, K.M.; Soccol, C.; Pandey, A. α-Amylases from Microbial Sources—An Overview on Recent Developments. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2006, 44, 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, G.; Vieille, C.; Savchenko, A.; Zeikus, J.G. Cloning, Sequencing, and Expression of the Gene Encoding Extracellular Alpha-Amylase from Pyrococcus furiosus and Biochemical Characterization of the Recombinant Enzyme. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 3569–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, C.L.; Russell, R.R.B. Intracellular α-Amylase of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 4711–4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.S.; Nimmagadda, A.; Sambasiva Rao, K.R.S. An Overview of the Microbial—Amylase Family. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2003, 2, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, G.; Krishnan, C. α-Amylase Production from Catabolite Derepressed Bacillus Subtilis KCC103 Utilizing Sugarcane Bagasse Hydrolysate. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 3044–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.M.D.; Magalhães, P.D.O.E. Application of Microbial α-Amylase in Industry—A Review. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2010, 41, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan, B. Highly Thermostable, Thermophilic, Alkaline, SDS and Chelator Resistant Amylase from a Thermophilic Bacillus sp. Isolate A3-15. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 3071–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbel, R.E.; Maktouf, S.; Massoud, E.B.; Bejar, S.; Chaabouni, S.E. New Thermostable Amylase from Bacillus Cohnii US147 with a Broad pH Applicability. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2009, 157, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.R.; Resende, J.T.V.; Guerra, E.P.; Lima, V.A.; Martins, M.D.; Knob, A. Enzymatic Conversion of Sweet Potato Granular Starch into Fermentable Sugars: Feasibility of Sweet Potato Peel as Alternative Substrate for α-Amylase Production. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 11, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.U.; Gu, B.G.; Jeong, J.Y.; Byun, S.M.; Shin, Y.C. Purification and Characterization of a Maltotetraose-Forming Alkaline (Alpha)-Amylase from an Alkalophilic Bacillus Strain, GM8901. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 3105–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pranay, K.; Padmadeo, S.R.; Prasad, B. Production of Amylase from Bacillus subtilis sp. Strain KR1 under Solid State Fermentation on Different Agrowastes. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Gigras, P.; Mohapatra, H.; Goswami, V.K.; Chauhan, B. Microbial α-Amylases: A Biotechnological Perspective. Process Biochem. 2003, 38, 1599–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Khan, M.S.; Khan, S.S.; Ahmad, W.; Zheng, L.; Shah, S.U.A.; Ullah, M.; Iqbal, A. Identification and Characterization of Thermophilic Amylase Producing Bacterial Isolates from the Brick Kiln Soil. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbalaei-Heidari, H.R.; Ziaee, A.-A.; Schaller, J.; Amoozegar, M. Purification and Characterization of an Extracellular Haloalkaline Protease Produced by the Moderately Halophilic Bacterium, Salinivibrio Sp. Strain AF-2004. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2007, 40, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senger, J.; Seitl, I.; Pross, E.; Fischer, L. Secretion of the Cytoplasmic and High Molecular Weight β-Galactosidase of Paenibacillus Wynnii with Bacillus Subtilis. Microb. Cell Factories 2024, 23, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demain, A.L.; Vaishnav, P. Production of Recombinant Proteins by Microbes and Higher Organisms. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009, 27, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewalt, V.; Shanahan, D.; Gregg, L.; La Marta, J.; Carrillo, R. The Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) Process for Industrial Microbial Enzymes. Ind. Biotechnol. 2016, 12, 295–302, Correction in Ind. Biotechnol. 2016, 12, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallmey, M.; Singh, A.; Ward, O.P. Developments in the Use of Bacillus Species for Industrial Production. Can. J. Microbiol. 2004, 50, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Zuo, Z.; Shi, G.-Y.; Wang, Z.-X. High Yield Recombinant Thermostable α-Amylase Production Using an Improved Bacillus Licheniformis System. Microb. Cell Factories 2009, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westers, L.; Westers, H.; Quax, W.J. Bacillus Subtilis as Cell Factory for Pharmaceutical Proteins: A Biotechnological Approach to Optimize the Host Organism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Cell Res. 2004, 1694, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, R.; Dutta, T.; Sheikh, J. Extraction of Amylase from the Microorganism Isolated from Textile Mill Effluent Vis a Vis Desizing of Cotton. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2019, 14, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burhan, A.; Nisa, U.; Gökhan, C.; Ömer, C.; Ashabil, A.; Osman, G. Enzymatic Properties of a Novel Thermostable, Thermophilic, Alkaline and Chelator Resistant Amylase from an Alkaliphilic Bacillus sp. Isolate ANT-6. Process Biochem. 2003, 38, 1397–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisburg, W.G.; Barns, S.M.; Pelletier, D.A.; Lane, D.J. 16S Ribosomal DNA Amplification for Phylogenetic Study. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.G.; Walker, D.C.; Mclnnes, R.R. E. coli Host Strains Significantly Affect the Quality of Small Scale Plasmid DNA Preparations Used for Sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993, 21, 1677–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spizizen, J. Transformation of Biochemically Deficient Strains of Bacillus subtilis by Deoxyribonucleate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1958, 44, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richts, B.; Hertel, R.; Potot, S.; Poehlein, A.; Daniel, R.; Schyns, G.; Prágai, Z.; Commichau, F.M. Complete Genome Sequence of the Prototrophic Bacillus subtilis subsp. Subtilis Strain SP1. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2020, 9, e00825-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, R.; Rogers, E.J. Transformation of Chemically Competent E. coli. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 529, pp. 329–336. ISBN 978-0-12-418687-3. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulos, C.; Spizizen, J. Requirements for Transformation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1961, 81, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojcic, L.; Despotovic, D.; Martinez, R.; Maurer, K.-H.; Schwaneberg, U. An Efficient Transformation Method for Bacillus subtilis DB104. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 94, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.L. Use of Dinitrosalicylic Acid Reagent for Determination of Reducing Sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate Structure Prediction of Biomolecular Interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLano, W.L. Pymol: An Open-Source Molecular Graphics Tool. CCP4 Newsl. Protein Crystallogr. 2002, 40, 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Guindon, S.; Dufayard, J.-F.; Lefort, V.; Anisimova, M.; Hordijk, W.; Gascuel, O. New Algorithms and Methods to Estimate Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies: Assessing the Performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010, 59, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teufel, F.; Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Johansen, A.R.; Gíslason, M.H.; Pihl, S.I.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; Von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 6.0 Predicts All Five Types of Signal Peptides Using Protein Language Models. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1023–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, R.; Noorwez, S.M.; Satyanarayana, T. Production and Partial Characterization of Thermostable and Calcium-Independent Alpha-Amylase of an Extreme Thermophile Bacillus thermooleovorans NP54. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 31, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hmidet, N.; Bayoudh, A.; Berrin, J.G.; Kanoun, S.; Juge, N.; Nasri, M. Purification and Biochemical Characterization of a Novel α-Amylase from Bacillus licheniformis NH1. Process Biochem. 2008, 43, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, J.K. A Differential Behavior of α-Amylase, in Terms of Catalytic Activity and Thermal Stability, in Response to Higher Concentration CaCl2. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 51, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viksø-Nielsen, A.; Andersen, C.; Hoff, T.; Pedersen, S. Development of New α-Amylases for Raw Starch Hydrolysis. Biocatal. Biotransform. 2009, 24, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yang, X.; Geng, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, Y.; Li, W.-J. Purification and Characterization of a Novel and Versatile α-Amylase from Thermophilic Anoxybacillus sp. YIM 342. Starch-Stärke 2015, 68, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Quadan, F.; Akel, H.; Natshi, R. Characteristics of a Novel, Highly Acid- and Thermo-Stable Amylase from Thermophilic Bacillus Strain HUTBS62 under Different Environmental Conditions. Ann. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machius, M.; Declerck, N.; Huber, R.; Wiegand, G. Kinetic Stabilization of Bacillus Licheniformis α-Amylase through Introduction of Hydrophobic Residues at the Surface. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 11546–11553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, P.P.; Dasgupta, D.; Ray, A.; Suman, S.K. Challenges and Prospects of Microbial α-Amylases for Industrial Application: A Review. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, N.; Rozeboom, H.J.; Lončar, N.; Slavić, M.Š.; Janssen, D.B.; Vujčić, Z. Characterization of the Starch Surface Binding Site on Bacillus paralicheniformis α-Amylase. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 1529–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machius, M.; Declerck, N.; Huber, R.; Wiegand, G. Activation of Bacillus licheniformis α-Amylase through a Disorder→order Transition of the Substrate-Binding Site Mediated by a Calcium–Sodium–Calcium Metal Triad. Structure 1998, 6, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manonmani, H.K.; Kunhi, A.A.M. Secretion to the Growth Medium of an α-Amylase by Escherichia coli Clones Carrying a Bacillus laterosporus Gene. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999, 15, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahhoseini, M.; Ziaee, A.-A.; Ghaemi, N. Expression and Secretion of an Alpha-Amylase Gene from a Native Strain of Bacillus licheniformis in Escherichia coli by T7 Promoter and Putative Signal Peptide of the Gene. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 95, 1250–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Xu, X.; Wu, Y.; Niu, T.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Liu, L. Advances and Prospects of Bacillus subtilis Cellular Factories: From Rational Design to Industrial Applications. Metab. Eng. 2018, 50, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Declerck, N.; Joyet, P.; Trosset, J.-Y.; Garnier, J.; Gaillardin, C. Hyperthermostable Mutants of Bacillus licheniformis α-Amylase: Multiple Amino Acid Replacements and Molecular Modelling. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 1995, 8, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muazzam, A.; Rashid, N.; Irshad, S.; Fatima, M. Soluble Expression of Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 27811 α-Amylase and Charachterization of Purified Recombinant Enzyme. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2019, 29, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Božić, N.; Ruiz, J.; López-Santín, J.; Vujčić, Z. Production and Properties of the Highly Efficient Raw Starch Digesting α-Amylase from a Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 9945a. Biochem. Eng. J. 2011, 53, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.; Kamal, M.; Ayatollahi, S.A.; Ali, M.; Ahmed, M. Single Step Purification of Novel Thermostable and Chelator Resistant Amylase from Bacillus licheniformis RM44 by Affinity Chromatography. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. IJPR 2017, 16, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Yuan, X.; He, N.; Zhuang, T.Z.; Wu, P.; Zhang, G. Expression of Bacillus licheniformis α-Amylase in Pichia Pastoris without Antibiotics-Resistant Gene and Effects of Glycosylation on the Enzymic Thermostability. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Rani, B.; Malik, K.; Avtar, R. Microbial Amylases: An Overview on Recent Advancement. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2019, 7, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Priyadharshini, R.; Gunasekaran, P. Site-Directed Mutagenesis of the Calcium-Binding Site of α-Amylase of Bacillus licheniformis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvd, D.; Fujimoto, Z.; Takase, K.; Matsumura, M.; Mizuno, H. Crystal Structure of Bacillus stearothermophilus A-Amylase: Possible Factors Determining the Thermostability. J. Biochem. 2001, 129, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Declerck, N.; Machius, M.; Wiegand, G.; Huber, R.; Gaillardin, C. Probing Structural Determinants Specifying High Thermostability in Bacillus licheniformis Alpha-Amylase. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 301, 1041–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshigi, N.; CHKANO, T.; Kamimura, M. Purification and Properties of an Amylase from Bacillus cereus NY-14. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1985, 49, 3369–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, H.; Sharma, K.; Gupta, J.; Soni, S. Production of a Thermostable α-Amylase from Bacillus sp. PS-7 by Solid State Fermentation and Its Synergistic Use in the Hydrolysis of Malt Starch for Alcohol Production. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltaş, N.; Dincer, B.; Ekinci, A.; Kolayli, S.; Adiguzel, A. Purification and Characterization of Extracellular α-Amylase from a Thermophilic Anoxybacillus thermarum A4 Strain. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2016, 59, e16160346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain/Plasmid | Genotype/Features | Reference/Source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | F′ 80ΔlacZ M15 (lacZYA-argF) U169 recA1 endA1hsdR17(rk−, mk+) phoA supE44-thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | [26] |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pLys | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−)gal dcm(DE3) pLysS (CmR) | Novagen |

| B. subtilis 168 | wild type (GRAS) | [27,28] |

| pHT01 | E. coli-B. subtilis shuttle vector, AmpR, CmR, Pgrac-promoter | NovoProLab |

| pET22b | pBR322 ori, f1 ori, AmpR, PT7-promoter | Novagen |

| pET22b-amyBL159-6His | amyBL159 gene cloned in to NdeI и XhoI restriction sites of pET22b vector | This work |

| pHT01-amyBL159-6His | amyBL159 gene cloned in to BamI и SmaI restriction sites of pHT01 vector | This work |

| Compound | Residual Specific Activity (%) of AmyBL159Ec | Residual Specific Activity (%) of AmyBL159Bs |

|---|---|---|

| Control * | 100 | 100 |

| NaCl (5 mM) | 76 | 102 |

| KCl (5 mM) | 93 | 92 |

| MnSO4 (5 mM) | 163 | 142 |

| MgSO4 (5 mM) | 82 | 75 |

| CaCl2 (5 mM) | 120 | 96 |

| SDS (1%) | 50 | 21 |

| EDTA (1 mM) | 85 | 68 |

| Enzyme Forms | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type BLA * | Double Mutation * | Triple Mutation 1 | Triple Mutation 2 (1BLI_A) * | Quadruple Mutation (1OB0_A) * | AmyBL159 (Position Corresponding to 1BLI_A or 1OB0_A) | |

| Residues | H133 | H133 | V133 | H133 | V133 | H134(133) |

| L134 | L134 | L134 | L134 | L134 | R135(134) | |

| N190 | N190 | F190 | F190 | F190 | N190 | |

| A209 | A209 | V209 | A209 | V209 | A210(209) | |

| Q264 | S264 | Q264 | S264 | S264 | Q265(264) | |

| N265 | Y265 | N265 | Y265 | Y265 | N266(265) | |

| Q393 | Q393 | Q393 | Q393 | Q393 | P394(393) | |

| A465 | A465 | A465 | A465 | E465 | E466(465) | |

| Stability, half-life, min | 14 * | 19 * | 384 * | 71 * | 447 * | 15 ** |

| Strain-Donor of α-Amylase B. licheniformis | pH Optimum | T-Optimum, °C | Stability, Half-Live | GenBank Acc. No. (RCSB Acc. No.) | Host Strain for Expression | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGMM159 | 4.0–12.0 | 75–95 | 15 min at 80 °C | no info | E. coli BL21(DE3), secreted | This work |

| MGMM159 | 4.0–12.0 | 45–75 | 15 min at 80 °C | no info | B. subtilis 168, secreted | This work |

| no info * | no info | no info | 71 min at 85 °C | 1BLI_A (1BLI.pdb, muts N190F, Q264S and N265Y) | E. coli HB2151 | [46,50] |

| no info | no info | no info | 447 min at 85 °C | 1OB0_A (1OB0.pdb, muts H133V; N190F; A209V; N264S, Q265Y) | E.coli HB2151 | [43,50] |

| ATCC 27811 | 8.0 | 70 | no info | no info | E. coli BL21-Codon Plus (DE3-RIPL) | [51] |

| ATCC 9945a | 6.5 | 90 | 90 min at 80 °C | JN042159.1 (6TOY, 6TOZ, 6TP0, 6TP1, 6TP2) | B. licheniformis ATCC 9945a | [45,52] |

| NH1 | 5.0–10.0 | 90 | 40 min at 80 °C | ABL75259.1 | E. coli BL21, secreted | [38] |

| RM44 | 5.0 | 100 | >120 min at 80 °C | no info | B. licheniformis RM44 | [53] |

| LB04 | 3.0 | 80 | no info | no info | B. licheniformis LB04 | [2] |

| WX-02 | 6.0–7.5 | 80 | 11 min at 70 °C | AKQ71831.1 | Pichia pastoris | [54] |

| WX-02 | 6.0–7.6 | 80 | 15 min at 70 °C | AKQ71831.1 | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | [54] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suleimanova, E.R.; Klochkova, E.A.; Validov, S.Z.; Kolomytseva, M.P.; Chernykh, A.M.; Trachtmann, N.V. Recombinant Forms of α-Amylase AmyBL159 from a Thermophilic Bacterium Bacillus licheniformis MGMM159: The Effect of the Expression System on the Enzyme Properties. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2747. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122747

Suleimanova ER, Klochkova EA, Validov SZ, Kolomytseva MP, Chernykh AM, Trachtmann NV. Recombinant Forms of α-Amylase AmyBL159 from a Thermophilic Bacterium Bacillus licheniformis MGMM159: The Effect of the Expression System on the Enzyme Properties. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2747. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122747

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuleimanova, Elvira R., Elizaveta A. Klochkova, Shamil Z. Validov, Marina P. Kolomytseva, Alexey M. Chernykh, and Natalia V. Trachtmann. 2025. "Recombinant Forms of α-Amylase AmyBL159 from a Thermophilic Bacterium Bacillus licheniformis MGMM159: The Effect of the Expression System on the Enzyme Properties" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2747. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122747

APA StyleSuleimanova, E. R., Klochkova, E. A., Validov, S. Z., Kolomytseva, M. P., Chernykh, A. M., & Trachtmann, N. V. (2025). Recombinant Forms of α-Amylase AmyBL159 from a Thermophilic Bacterium Bacillus licheniformis MGMM159: The Effect of the Expression System on the Enzyme Properties. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2747. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122747