Invasive Pneumococcal Diseases Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy (2018–2023)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Bacterial Strains and Serotyping

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

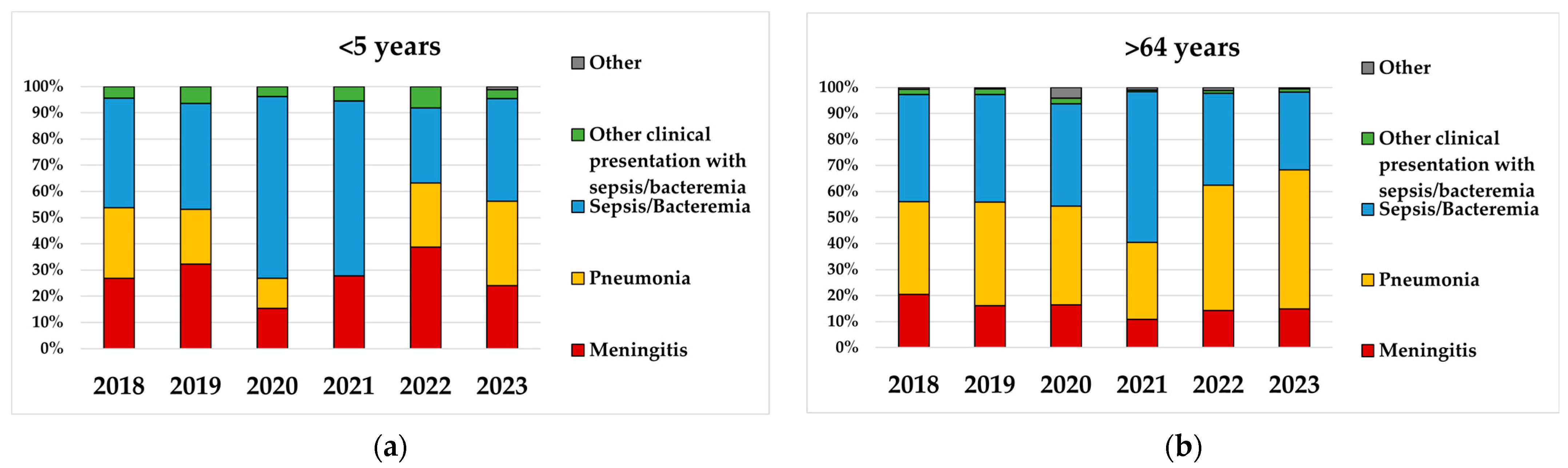

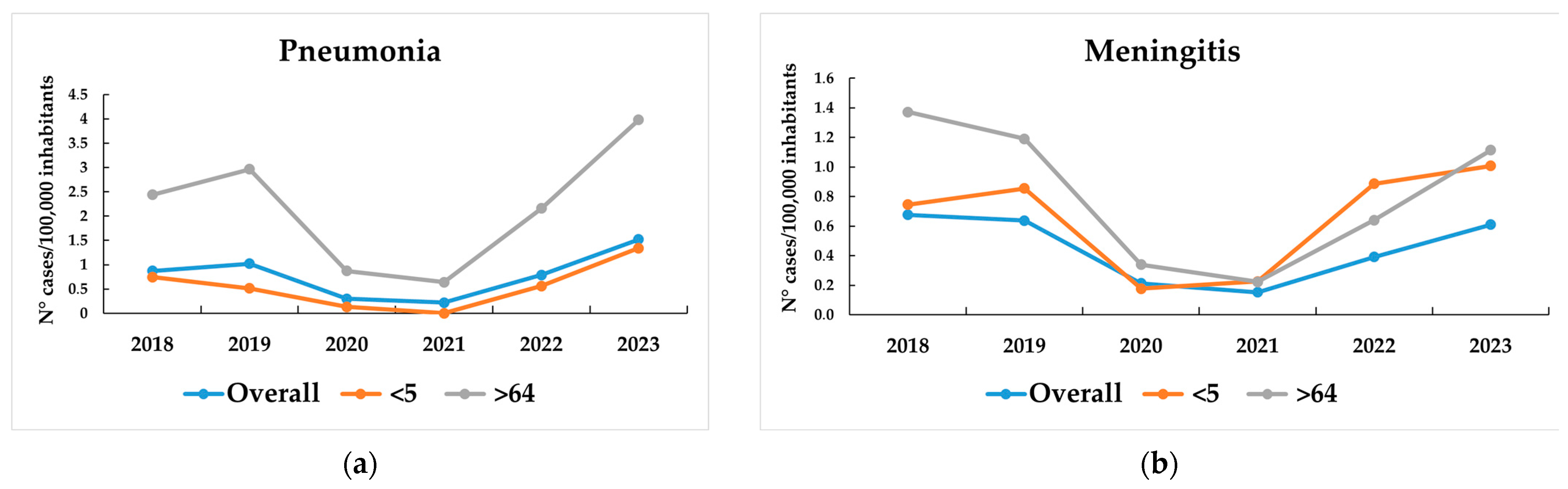

3.1. IPD Incidence

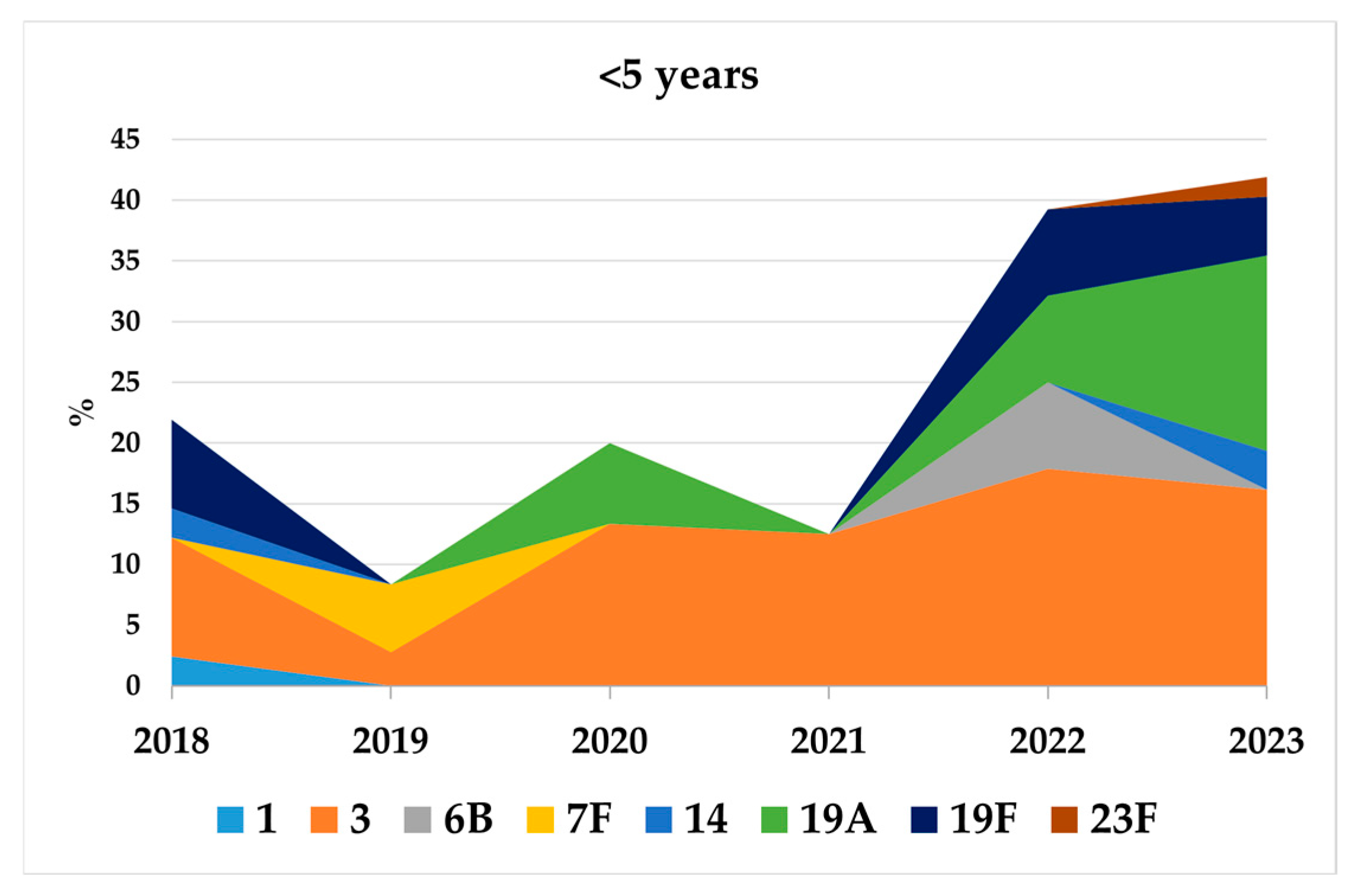

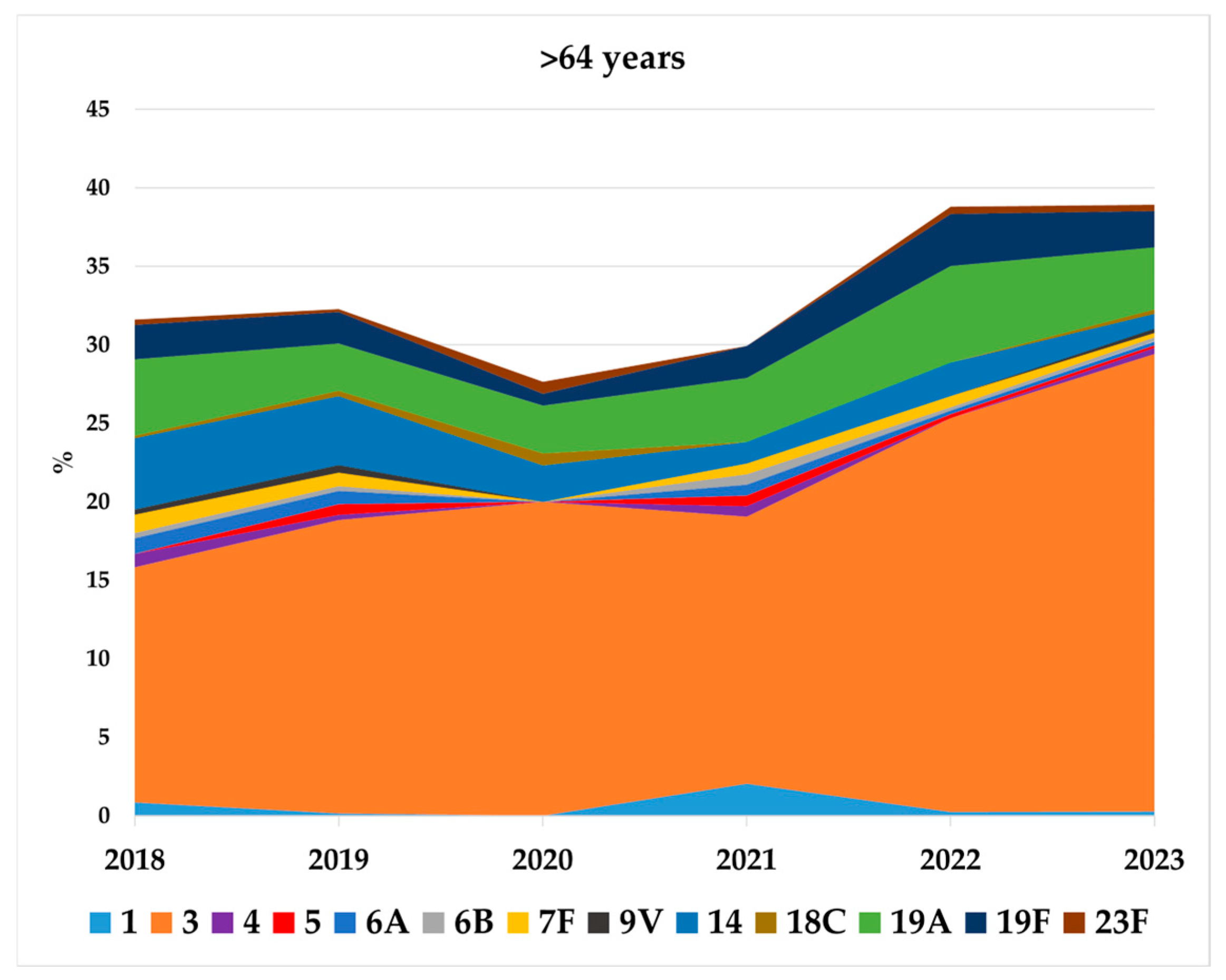

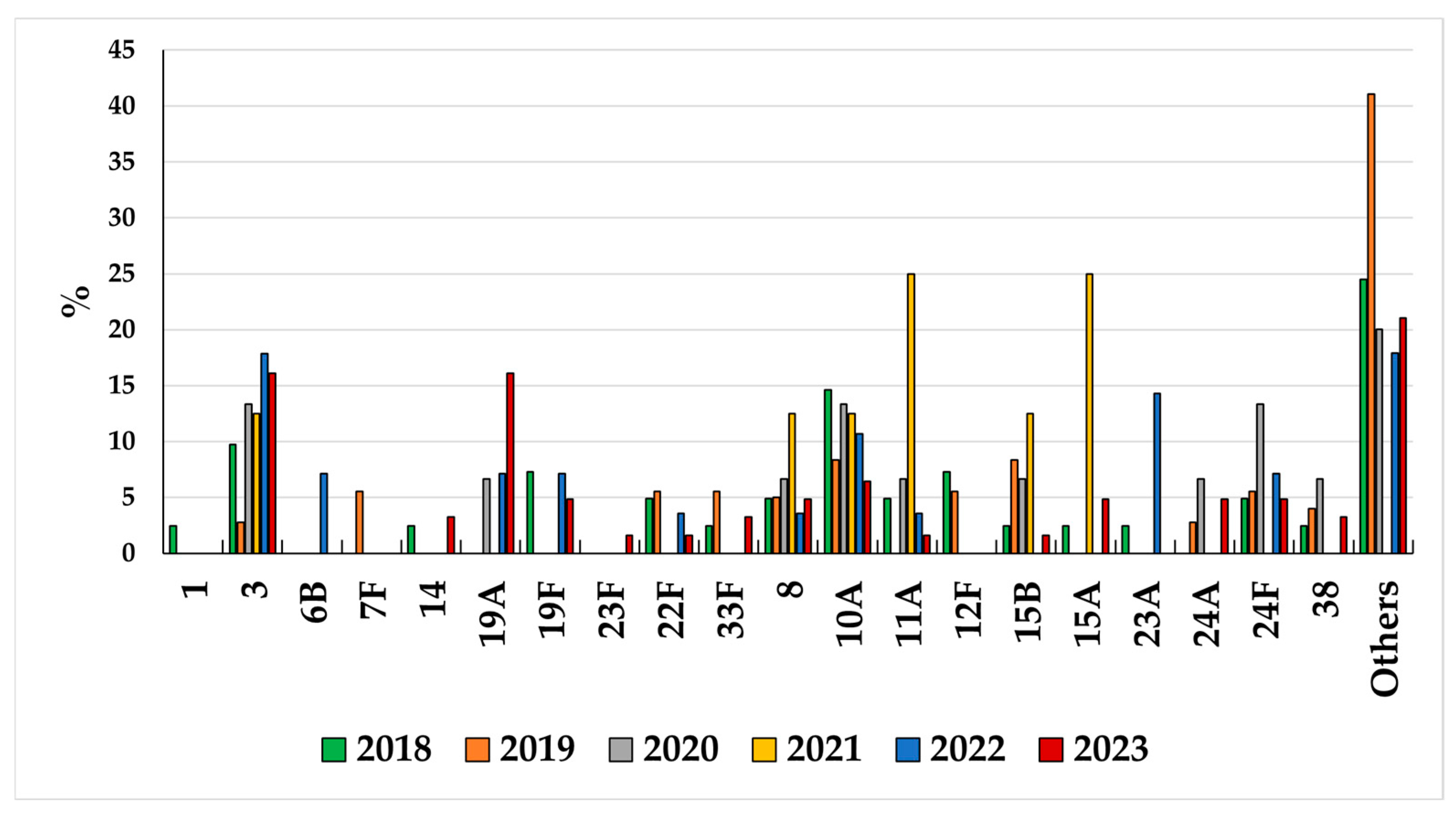

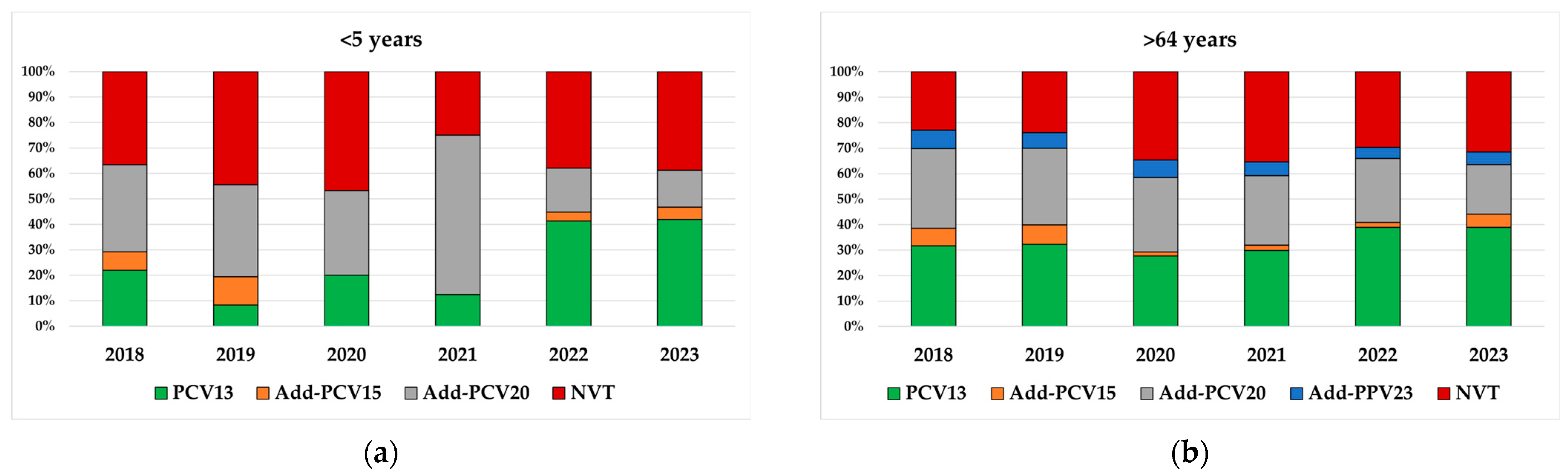

3.2. Serotype Distribution in Children <5 Years and Adults Aged >64 Years

3.3. Serotype Distribution by New Conjugate Vaccines in Children <5 Years and Adults Aged >64 Years

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bennett, J.C.; Deloria Knoll, M.; Kagucia, E.W.; Garcia Quesada, M.; Zeger, S.L.; Hetrich, M.K.; Yang, Y.; Herbert, C.; Ogyu, A.; Cohen, A.L.; et al. Global impact of ten-valent and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines on invasive pneumococcal disease in all ages (the PSERENADE project): A global surveillance analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 457–470, Erratum in Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ladhani, S.N.; Collins, S.; Djennad, A.; Sheppard, C.L.; Borrow, R.; Fry, N.K.; Andrews, N.J.; Miller, E.; Ramsay, M.E. Rapid increase in non-vaccine serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales, 2000–2017: A prospective national observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 441–451, Erratum in Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia Quesada, M.; Peterson, M.E.; Bennett, J.C.; Hayford, K.; Zeger, S.L.; Yang, Y.; Hetrich, M.K.; Feikin, D.R.; Cohen, A.L.; von Gottberg, A.; et al. Serotype distribution of remaining invasive pneumococcal disease after extensive use of ten-valent and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (the PSERENADE project): A global surveillance analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 445–456, Erratum in Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Calendario Vaccinale. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/new/it/tema/vaccinazioni/calendario-vaccinale/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Dati Coperture Vaccinali. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/new/it/tema/vaccinazioni/dati-coperture-vaccinali/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- D’Ancona, F.C.; Caporali, M.G.; Del Manso, M.; Giambi, C.; Camilli, R.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Del Grosso, M.; Iannazzo, S.; Rizzuto, E.; Pantosti, A. Invasive pneumococcal disease in children and adults in seven Italian regions after the introduction of the conjugate vaccine, 2008–2014. Epidemiol. Prev. 2015, 39, 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Camilli, R.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Del Grosso, M.; Pimentel de Araujo, F.; Caporali, M.G.; Del Manso, M.; Gherardi, G.; D’Ancona, F.; Pantosti, A.; Pneumococcal Surveillance, G. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7 and PCV13) on pneumococcal invasive diseases in Italian children and insight into evolution of pneumococcal population structure. Vaccine 2017, 35, 4587–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueggemann, A.B.; Jansen van Rensburg, M.J.; Shaw, D.; McCarthy, N.D.; Jolley, K.A.; Maiden, M.C.J.; van der Linden, M.P.G.; Amin-Chowdhury, Z.; Bennett, D.E.; Borrow, R.; et al. Changes in the incidence of invasive disease due to Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria meningitidis during the COVID-19 pandemic in 26 countries and territories in the Invasive Respiratory Infection Surveillance Initiative: A prospective analysis of surveillance data. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e360–e370, Erratum in Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dirkx, K.K.T.; Mulder, B.; Post, A.S.; Rutten, M.H.; Swanink, C.M.A.; Wertheim, H.F.L.; Cremers, A.J.H. The drop in reported invasive pneumococcal disease among adults during the first COVID-19 wave in the Netherlands explained. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 111, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagan, R.; van der Beek, B.A.; Ben-Shimol, S.; Greenberg, D.; Shemer-Avni, Y.; Weinberger, D.M.; Danino, D. The COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity for unravelling the causative association between respiratory viruses and pneumococcus-associated disease in young children: A prospective study. EBioMedicine 2023, 90, 104493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besteman, S.B.; Bogaert, D.; Bont, L.; Mejias, A.; Ramilo, O.; Weinberger, D.M.; Dagan, R. Interactions between respiratory syncytial virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae in the pathogenesis of childhood respiratory infections: A systematic review. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streptococcus pneumoniae Detection and Serotyping Using PCR. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/strep-lab/php/pneumococcus/serotyping-using-pcr.html#cdc_generic_section_2-real-time-pcr (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Lodi, L.; Catamero, F.; Sarli, W.M.; Moriondo, M.; Nieddu, F.; Ferraro, E.; Citera, F.; Astorino, V.; Giovannini, M.; Voarino, M.; et al. Serotype 3 invasive pneumococcal disease in Tuscany across the eras of conjugate vaccines (2005–2024) and anthropic-driven respiratory virus fluctuations. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2025, 21, 2510005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.H.; Bryson, K.; Freystatter, K.; Pichon, B.; Edwards, G.; Charalambous, B.M.; Gillespie, S.H. Sequetyping: Serotyping Streptococcus pneumoniae by a single PCR sequencing strategy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 2419–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Abad, R.; Amin-Chowdhury, Z.; Bautista, A.; Bennett, D.; Broughton, K.; Cao, B.; Casanova, C.; Choi, E.H.; Chu, Y.W.; et al. Trends in invasive bacterial diseases during the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic: Analyses of prospective surveillance data from 30 countries and territories in the IRIS Consortium. Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e582–e593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, A.; Levy, C.; Angoulvant, F.; Auvrignon, A.; Gembara, P.; Danis, K.; Vaux, S.; Levy-Bruhl, D.; van der Werf, S.; Bechet, S.; et al. Association of Nonpharmaceutical Interventions During the COVID-19 Pandemic With Invasive Pneumococcal Disease, Pneumococcal Carriage, and Respiratory Viral Infections Among Children in France. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2218959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, R.; Abu Sin, M.; Tenenbaum, T.; Toepfner, N.; Berner, R.; Buda, S.; Schlaberg, J.; Schonfeld, V.; Reinacher, U.; van der Linden, M.; et al. The Increase in Invasive Bacterial Infections With Respiratory Transmission in Germany, 2022/2023. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2024, 121, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perniciaro, S.; van der Linden, M.; Weinberger, D.M. Reemergence of Invasive Pneumococcal Disease in Germany During the Spring and Summer of 2021. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 1149–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, R.; Ashman, M.; Taha, M.K.; Varon, E.; Angoulvant, F.; Levy, C.; Rybak, A.; Ouldali, N.; Guiso, N.; Grimprel, E. Pediatric Infectious Disease Group (GPIP) position paper on the immune debt of the COVID-19 pandemic in childhood, how can we fill the immunity gap? Infect. Dis. Now. 2021, 51, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munro, A.P.; House, T. Cycles of susceptibility: Immunity debt explains altered infectious disease dynamics post -pandemic. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, ciae493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagasawa, M. Verification of Immune Debts in Children Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic from an Epidemiological and Clinical Perspective. Immuno 2025, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghirardo, S.; Ullmann, N.; Zago, A.; Ghezzi, M.; Minute, M.; Madini, B.; D’Auria, E.; Basile, C.; Castelletti, F.; Chironi, F.; et al. Increased bronchiolitis burden and severity after the pandemic: A national multicentric study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2024, 50, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrashed, R.; Almeshawi, I.; Alshammari, A.; Alhamoud, W.; AlShathri, R.; Alotaibi, A.; Saja, D.; Algoraini, Y. Burden of bronchiolitis post-COVID-19 pandemic in children less than 2 years old in 2021–2024: Experience from a tertiary center in Saudi Arabia. BMC Pediatr. 2025, 25, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouldali, N.; Deceuninck, G.; Lefebvre, B.; Gilca, R.; Quach, C.; Brousseau, N.; Tapiero, B.; De Wals, P. Increase of invasive pneumococcal disease in children temporally associated with RSV outbreak in Quebec: A time-series analysis. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2023, 19, 100448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocchio, S.; Cozzolino, C.; Furlan, P.; Cozza, A.; Tonon, M.; Russo, F.; Saia, M.; Baldo, V. Pneumonia-Related Hospitalizations among the Elderly: A Retrospective Study in Northeast Italy. Diseases 2024, 12, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trobajo-Sanmartin, C.; Portillo, M.E.; Navascues, A.; Martinez-Baz, I.; Ezpeleta, C.; Castilla, J. Unusually high incidence of pneumonia in Navarre, Spain, 2023–2024. Enfermedades Infecc. Microbiol. Clínica 2025, 43, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansbury, L.; McKeever, T.M.; Lawrence, H.; Pick, H.; Baskaran, V.; Edwards-Pritchard, R.; Matthews, L.; Bailey, H.; Ashton, D.; Bendall, L.; et al. Pneumococcal pneumonia trends in adults hospitalised with community-acquired pneumonia over 10 years (2013–2023) and the role of serotype 3. Thorax 2025, 80, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invasive Pneumococcal Disease—Annual Epidemiological Report for 2022. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/invasive-pneumococcal-disease-annual-epidemiological-report-2022 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Bertran, M.; Amin-Chowdhury, Z.; Sheppard, C.L.; Eletu, S.; Zamarreno, D.V.; Ramsay, M.E.; Litt, D.; Fry, N.K.; Ladhani, S.N. Increased Incidence of Invasive Pneumococcal Disease among Children after COVID-19 Pandemic, England. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 1669–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Nguyen, J.L.; Alfred, T.; Perdrizet, J.; Cane, A.; Arguedas, A. PCV13 Pediatric Routine Schedule Completion and Adherence Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2022, 11, 2141–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taine, M.; Offredo, L.; Drouin, J.; Toubiana, J.; Weill, A.; Zureik, M.; Dray-Spira, R. Mandatory Infant Vaccinations in France During the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 666848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Marcos, M.; Zabaleta-Del-Olmo, E.; Gomez-Duran, E.L.; Rene-Rene, A.; Cabezas-Pena, C. Impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on routine childhood vaccination coverage rates in Catalonia (Spain): A public health register-based study. Public. Health 2023, 218, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, S.A. Correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2010, 17, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deceuninck, G.; Brousseau, N.; Lefebvre, B.; Quach, C.; Tapiero, B.; Bui, Y.G.; Desjardins, M.; De Wals, P. Effectiveness of thirteen-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to prevent serotype 3 invasive pneumococcal disease in Quebec in children, Canada. Vaccine 2023, 41, 5486–5489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, R.; Patterson, S.; Juergens, C.; Greenberg, D.; Givon-Lavi, N.; Porat, N.; Gurtman, A.; Gruber, W.C.; Scott, D.A. Comparative immunogenicity and efficacy of 13-valent and 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in reducing nasopharyngeal colonization: A randomized double-blind trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sings, H.L.; De Wals, P.; Gessner, B.D.; Isturiz, R.; Laferriere, C.; McLaughlin, J.M.; Pelton, S.; Schmitt, H.J.; Suaya, J.A.; Jodar, L. Effectiveness of 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Against Invasive Disease Caused by Serotype 3 in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 68, 2135–2143, Erratum in Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 1684–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shirley, M. 20-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine: A Review of Its Use in Adults. Drugs 2022, 82, 989–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.J.; Waight, P.A.; Burbidge, P.; Pearce, E.; Roalfe, L.; Zancolli, M.; Slack, M.; Ladhani, S.N.; Miller, E.; Goldblatt, D. Serotype-specific effectiveness and correlates of protection for the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: A postlicensure indirect cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, M.R.; Link-Gelles, R.; Schaffner, W.; Lynfield, R.; Holtzman, C.; Harrison, L.H.; Zansky, S.M.; Rosen, J.B.; Reingold, A.; Scherzinger, K.; et al. Effectiveness of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for prevention of invasive pneumococcal disease in children in the USA: A matched case-control study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waight, P.A.; Andrews, N.J.; Ladhani, S.N.; Sheppard, C.L.; Slack, M.P.; Miller, E. Effect of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales 4 years after its introduction: An observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 535–543, Erratum in Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oligbu, G.; Collins, S.; Andrews, N.; Sheppard, C.L.; Fry, N.K.; Slack, M.P.E.; Borrow, R.; Ladhani, S.N. Characteristics and Serotype Distribution of Childhood Cases of Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Following Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccination in England and Wales, 2006–2014. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 65, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.L.; Barson, W.J.; Lin, P.L.; Romero, J.R.; Bradley, J.S.; Tan, T.Q.; Pannaraj, P.S.; Givner, L.B.; Hulten, K.G. Invasive Pneumococcal Disease in Children’s Hospitals: 2014–2017. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20190567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockett, R.J.; Oftadeh, S.; Bachmann, N.L.; Timms, V.J.; Kong, F.; Gilbert, G.L.; Sintchenko, V. Genome-wide analysis of Streptococcus pneumoniae serogroup 19 in the decade after the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in Australia. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, M.; Mereckiene, J.; Cotter, S.; Murchan, S.; Lo, S.W.; McGee, L.; Breiman, R.F.; Cunney, R.; Humphreys, H.; Bentley, S.D.; et al. Using genomics to examine the persistence of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 19A in Ireland and the emergence of a sub-clade associated with vaccine failures. Vaccine 2021, 39, 5064–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zintgraff, J.; Gagetti, P.; Sanchez Eluchans, N.; Marchetti, P.; Moscoloni, M.A.; Argentina Spn Working, G.; Lara, C.S.; Corso, A. Evolving Landscape of Paediatric Pneumococcal Meningitis in Argentina (2013–2023). Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Costa, C.; Gomes-Silva, J.; Pinho, M.; Friaes, A.; Subtil-Limpo, F.; Ramirez, M.; Melo-Cristino, J.; Portuguese Group for the Study of Streptococcal, I.; the Portuguese Study Group of Invasive Pneumococcal Disease of the Pediatric Infectious Disease, S. Rebound of pediatric invasive pneumococcal disease in Portugal after the COVID-19 pandemic was not associated with significant serotype changes. J. Infect. 2024, 89, 106242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Garcia, C.; Sempere, J.; de Miguel, S.; Hita, S.; Ubeda, A.; Vidal, E.J.; Llorente, J.; Limia, A.; de Miguel, A.G.; Sanz, J.C.; et al. Surveillance of invasive pneumococcal disease in Spain exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (2019–2023). J. Infect. 2024, 89, 106204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouldali, N.; Varon, E.; Levy, C.; Angoulvant, F.; Georges, S.; Ploy, M.C.; Kempf, M.; Cremniter, J.; Cohen, R.; Bruhl, D.L.; et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease incidence in children and adults in France during the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era: An interrupted time-series analysis of data from a 17-year national prospective surveillance study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, N.; Chang, B.; Ishiwada, N.; Cho, Y.; Nishi, J.; Okada, K.; Fujieda, M.; Oda, M.; Saitoh, A.; Hosoya, M.; et al. Nationwide population-based surveillance of invasive pneumococcal disease in children in Japan (2014–2022): Impact of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccine 2025, 54, 127138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Garcia, C.; Gonzalez-Diaz, A.; Domenech, M.; Llamosi, M.; Ubeda, A.; Sanz, J.C.; Garcia, E.; Ardanuy, C.; Sempere, J.; Yuste, J. The rise of serotype 8 is associated with lineages and mutations in the capsular operon with different potential to produce invasive pneumococcal disease. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2025, 14, 2521845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platt, H.L.; Greenberg, D.; Tapiero, B.; Clifford, R.A.; Klein, N.P.; Hurley, D.C.; Shekar, T.; Li, J.; Hurtado, K.; Su, S.C.; et al. A Phase II Trial of Safety, Tolerability and Immunogenicity of V114, a 15-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine, Compared With 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in Healthy Infants. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2020, 39, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platt, H.L.; Cardona, J.F.; Haranaka, M.; Schwartz, H.I.; Narejos Perez, S.; Dowell, A.; Chang, C.J.; Dagan, R.; Tamms, G.M.; Sterling, T.; et al. A phase 3 trial of safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of V114, 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, compared with 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in adults 50 years of age and older (PNEU-AGE). Vaccine 2022, 40, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 2018–2019 | 2020–2021 | 2022–2023 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (N°) | Incidence /100,000 | Cases (N°) | Incidence /100,000 | Cases (N°) | Incidence /100,000 | IRR 2020–2021 vs. 2018–2019 (95% CI) | IRR 2022–2023 vs. 2018–2019 (95% CI) | IRR 2022–2023 vs. 2020–2021 (95% CI) | |

| <2 years old | 83 | 4.6 | 31 | 1.9 | 91 | 5.7 | 0.78 (0.42–1.44) * | 1.40 (0.93–2.11) * | 1.79 (1.03–3.13) * |

| PCV13 | 6 | 2 | 18 | 1.72 (0.34–8.67) * | 2.48 (0.92–6.70) * | 1.44 (0.33–6.26) * | |||

| Non-PCV13 | 43 | 14 | 44 | 0.59 (0.30–1.15) * | 1.35 (0.85–2.13) * | 2.29 (1.24–4.21) * | |||

| 2–4 years old | 46 | 1.6 | 13 | 0.46 | 45 | 1.7 | 0.44 (0.18–1.03) * | 0.97 (0.56–1.68) * | 2.22 (1.04–4.71) * |

| PCV13 | 6 | 2 | 20 | 0.68 (0.09–4.85) * | 3.37 (1.06–10.70) * | 4.98 (1.09–22.77) * | |||

| Non-PCV13 | 26 | 7 | 15 | 0.47 (0.19–1.20) * | 0.56 (0.29–1.12) * | 1.19 (0.48–2.97) * | |||

| 18–64 years old | 1.116 | 1.5 | 365 | 0.50 | 928 | 1.3 | 0.33 (0.29–0.36) | 0.83 (0.78–0.89) | 2.54 (2.38–2.71) |

| PCV13 | 186 | 59 | 245 | 0.32 (0.24–0.41) | 1.32 (1.16–1.49) | 4.15 (3.65–4.71) | |||

| PPV23 | 477 | 198 | 316 | 0.42 (0.36–0.48) | 0.66 (0.59–0.74) | 1.6 (1.42–1.78) | |||

| Add-PPV23 | 282 | 71 | 235 | 0.25 (0.20–0.32) | 0.83 (0.73–0.95) | 3.31 (2.9–3.76) | |||

| NVT | 171 | 37 | 132 | 0.22 (0.15–0.3) | 0.77 (0.65–0.92) | 3.57 (2.98–4.23) | |||

| >64 years old | 1.918 | 7.0 | 581 | 2.1 | 1.687 | 6.0 | 0.30 (0.28–0.33) | 0.88 (0.84–0.92) | 2.9 (2.77–3.05) |

| PCV13 | 369 | 79 | 447 | 0.21 (0.17–0.27) | 1.21 (1.1–1.33) | 5.66 (5.15–6.21) | |||

| PPV23 | 741 | 305 | 535 | 0.41 (0.37–0.46) | 0.72 (0.66–0.79) | 1.75 (1.61–1.91) | |||

| Add-PPV23 | 530 | 100 | 349 | 0.19 (0.15–0.23) | 0.66 (0.59–0.73) | 3.49 (3.13–3.88) | |||

| NVT | 278 | 97 | 356 | 0.35 (0.28–0.43) | 1.28 (1.15–1.42) | 3.67 (3.3–4.07) | |||

| TOTAL | 3.226 | 3.1 | 1.005 | 0.96 | 2.839 | 2.7 | 0.31 (0.29–0.33) | 0.88 (0.85–0.91) | 2.82 (2.72–2.93) |

| PCV13 | 591 | 144 | 756 | 0.24 (0.21–0.29) | 1.28 (1.19–1.37) | 5.25 (4.88–5.64) | |||

| Non-PCV13 | 1396 | 337 | 1208 | 0.24 (0.22–0.27) | 0.87 (0.82–0.92) | 3.58 (3.39–3.79) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Camilli, R.; Giancristofaro, S.; Boros, S.; Bellini, B.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Urciuoli, R.; Del Grosso, M.; Pantosti, A.; Palamara, A.T.; D’Ancona, F. Invasive Pneumococcal Diseases Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy (2018–2023). Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2734. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122734

Camilli R, Giancristofaro S, Boros S, Bellini B, D’Ambrosio F, Urciuoli R, Del Grosso M, Pantosti A, Palamara AT, D’Ancona F. Invasive Pneumococcal Diseases Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy (2018–2023). Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2734. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122734

Chicago/Turabian StyleCamilli, Romina, Sara Giancristofaro, Stefano Boros, Benedetta Bellini, Fabio D’Ambrosio, Roberta Urciuoli, Maria Del Grosso, Annalisa Pantosti, Anna Teresa Palamara, and Fortunato D’Ancona. 2025. "Invasive Pneumococcal Diseases Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy (2018–2023)" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2734. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122734

APA StyleCamilli, R., Giancristofaro, S., Boros, S., Bellini, B., D’Ambrosio, F., Urciuoli, R., Del Grosso, M., Pantosti, A., Palamara, A. T., & D’Ancona, F. (2025). Invasive Pneumococcal Diseases Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy (2018–2023). Microorganisms, 13(12), 2734. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122734