Moraxella osloensis Isolated from the Intraoperative Field After Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Microbiological Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Case Description

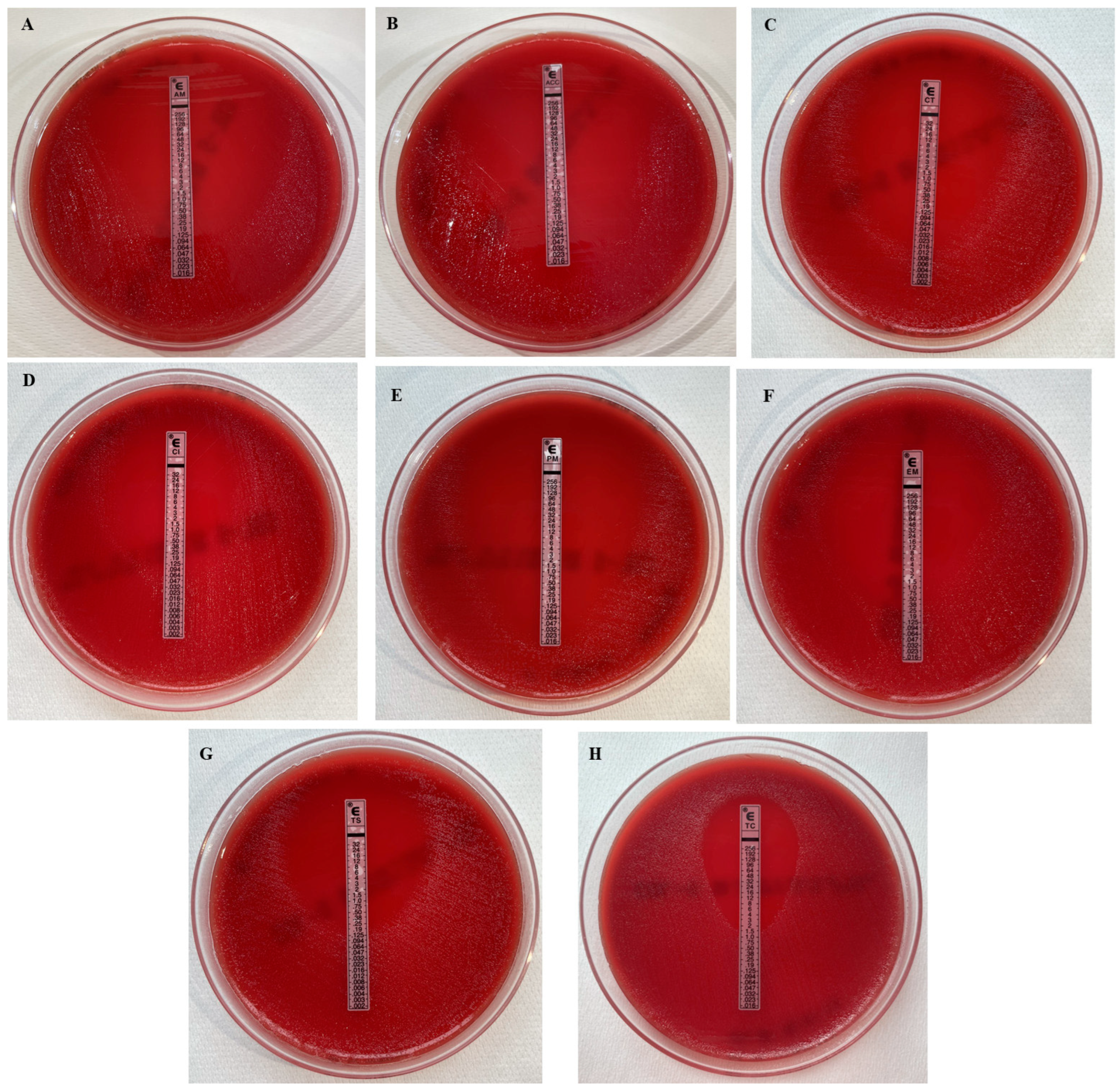

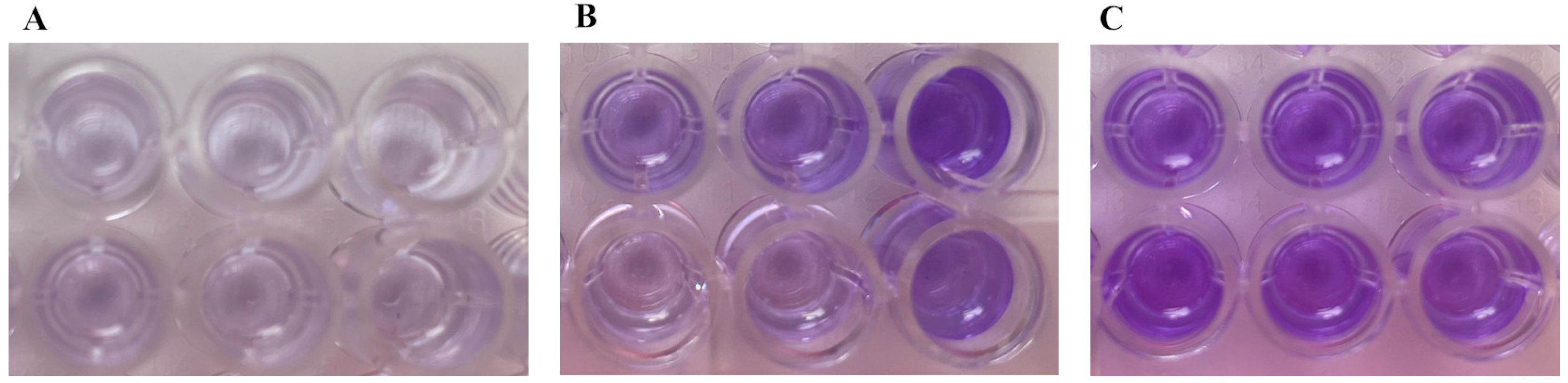

3.2. Microbiological Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonnevialle, N.; Dauzères, F.; Toulemonde, J.; Elia, F.; Laffosse, J.-M.; Mansat, P. Periprosthetic Shoulder Infection: An Overview. EFORT Open Rev. 2017, 2, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duvall, G.; Kaveeshwar, S.; Sood, A.; Klein, A.; Williams, K.; Kolakowski, L.; Lai, J.; Enobun, B.; Hasan, S.A.; Henn, R.F.; et al. Benzoyl Peroxide Use Transiently Decreases Cutibacterium Acnes Load on the Shoulder. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2020, 29, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, J.E.; Matsen, F.A.; Whitson, A.J.; Bumgarner, R.E. Cutibacterium Subtype Distribution on the Skin of Primary and Revision Shoulder Arthroplasty Patients. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2020, 29, 2051–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, J.E.; Neradilek, M.B.; Russ, S.M.; Matsen, F.A. Preoperative Skin Cultures Are Predictive of Propionibacterium Load in Deep Cultures Obtained at Revision Shoulder Arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2018, 27, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadler, B.K.; Mehta, S.S.; Funk, L. Propionibacterium Acnes Infection after Shoulder Surgery. Int. J. Shoulder Surg. 2015, 9, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, E.Y.; Ouseph, A.; Badejo, M.; Lund, J.; Bettacchi, C.; Garofalo, R.; Krishnan, S.G. Success of Staged Revision Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty in Eradication of Periprosthetic Joint Infection. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2023, 32, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, B.C.; Swanson, D.R.; Marmor, W.A.; Gibb, B.; Komatsu, D.E.; Wang, E.D. The Relationship between Bacterial Load and Initial Run Time of a Surgical Helmet. J. Shoulder Elb. Arthroplast. 2022, 6, 24715492221142688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsen, F.A.; Whitson, A.J.; Hsu, J.E. While Home Chlorhexidine Washes Prior to Shoulder Surgery Lower Skin Loads of Most Bacteria, They Are Not Effective against Cutibacterium (Propionibacterium). Int. Orthop. (SICOT) 2020, 44, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsen, F.A.; Whitson, A.J.; Pottinger, P.S.; Neradilek, M.B.; Hsu, J.E. Cutaneous Microbiology of Patients Having Primary Shoulder Arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2020, 29, 1671–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.A.; Moverman, M.A.; Da Silva, A.Z.; Chalmers, P.N. Preventing Infections in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2024, 17, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P.Y.; Fomunung, C.; Lavin, A.; Daji, A.; Jackson, G.R.; Sabesan, V.J. Outcomes Following Revision Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty for Infection. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2024, 33, 2433–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilat, R.; Mitchnik, I.; Beit Ner, E.; Shohat, N.; Tamir, E.; Weil, Y.A.; Lazarovitch, T.; Agar, G. Bacterial Contamination of Protective Lead Garments in an Operating Room Setting. J. Infect. Prev. 2020, 21, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonna, D.; Allizond, V.; Bellato, E.; Banche, G.; Cuffini, A.M.; Castoldi, F.; Rossi, R. Single versus Double Skin Preparation for Infection Prevention in Proximal Humeral Fracture Surgery. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 8509527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Diek, F.M.; Pruijn, N.; Spijkers, K.M.; Mulder, B.; Kosse, N.M.; Dorrestijn, O. The Presence of Cutibacterium Acnes on the Skin of the Shoulder after the Use of Benzoyl Peroxide: A Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blinded, Randomized Trial. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2020, 29, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panther, E.J.; Hao, K.A.; Wright, J.O.; Schoch, J.J.; Ritter, A.S.; King, J.J.; Wright, T.W.; Schoch, B.S. Techniques for Decreasing Bacterial Load for Open Shoulder Surgery. JBJS Rev. 2022, 10, e22.00141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symonds, T.; Grant, A.; Doma, K.; Hinton, D.; Wilkinson, M.; Morse, L. The Efficacy of Topical Preparations in Reducing the Incidence of Cutibacterium Acnes at the Start and Conclusion of Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2022, 31, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhatib, N.J.; Younis, M.H.; Alobaidi, A.S.; Shaath, N.M. An Unusual Osteomyelitis Caused by Moraxella osloensis: A Case Report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2017, 41, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, C.; Moolman, N.; MacKay, C.; Hatchette, T.F.; Trites, J.; Taylor, S.M.; Rigby, M.H.; Hart, R.D. Bacterial Contamination of Surgical Loupes and Headlights. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2019, 133, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, L.N.; Kurdy, N.M.; Hassan, I.; Aster, A.S. Septic Arthritis of the Ankle Due to Moraxella osloensis. Foot Ankle Surg. 2007, 13, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratibha, D.; Lakshmi, D.; Gomathy, D.; Kumar, P.; Vanishree, Y.M. Moraxella osloensis: Septic Arthritis. Saudi J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2017, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Quoilin, M.; Vu, P.D.; Bansal, V.; Chen, J.W. Septic Arthritis of the Cervical Facet Joint: Clinical Report and Review of the Literature. Pain. Pract. 2024, 24, 1074–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, J.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Carr, A. Questionnaire on the Perception of Patients about Shoulder Surgery. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. Vol. 1996, 78, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbart, M.K.; Gerber, C. Comparison of the Subjective Shoulder Value and the Constant Score. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2007, 16, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.J.; Grimm, N.L.; Jimenez, A.E.; Shea, K.P.; Mazzocca, A.D. Is There Value in the Routine Practice of Discarding the Incision Scalpel from the Surgical Field to Prevent Deep Wound Contamination with Cutibacterium Acnes? J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2021, 30, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleri, J.; Petkar, H.M.; Husain, A.A.M.; Almaslamani, M.A.; Omrani, A.S. Moraxella osloensis Bacteremia, a Case Series and Review of the Literature. IDCases 2022, 27, e01450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, G.D.; Simpson, W.A.; Younger, J.J.; Baddour, L.M.; Barrett, F.F.; Melton, D.M. Adherence of coagulase-negative staphylococci to plastic tissue culture plates: A quantitative model for the adherence of staphylococci to medical devices. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1985, 22, 996–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccioni, C.B.; Woodbridge, A.B.; Balestro, J.-C.Y.; Figtree, M.C.; Hudson, B.J.; Cass, B.; Young, A.A. Low Rate of Propionibacterium Acnes in Arthritic Shoulders Undergoing Primary Total Shoulder Replacement Surgery Using a Strict Specimen Collection Technique. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2015, 24, 1206–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauzenberger, L.; Grieb, A.; Hexel, M.; Laky, B.; Anderl, W.; Heuberer, P. Infections Following Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair: Incidence, Risk Factors, and Prophylaxis. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2017, 25, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsen, F.A.; Whitson, A.; Hsu, J.E. Preoperative Skin Cultures Predict Periprosthetic Infections in Revised Shoulder Arthroplasties: A Preliminary Report. JBJS Open Access 2020, 5, e20.00095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudek, R.; Brobeil, A.; Brüggemann, H.; Sommer, F.; Gattenlöhner, S.; Gohlke, F. Cutibacterium Acnes Is an Intracellular and Intra-Articular Commensal of the Human Shoulder Joint. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2021, 30, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajita, Y.; Iwahori, Y.; Harada, Y.; Takahashi, R.; Deie, M. Incidence of Cutibacterium Acnes in Open Shoulder Surgery. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 2021, 83, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmens, L.; Geelen, H.; Depypere, M.; Munter, P.D.; Verhaegen, F.; Zimmerli, W.; Nijs, S.; Debeer, P.; Metsemakers, W.-J. Management of Periprosthetic Infection after Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2021, 30, 2514–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchman, A.L.; Pickett, M.J.; Mann, L.; Ament, M.E. Central Venous Catheter Infection Caused by Moraxella osloensis in a Patient Receiving Home Parenteral Nutrition. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1993, 17, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.S.; Ruth, A.; Coffin, S.E. Infection Due to Moraxella osloensis: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 30, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuori-Holopainen, E.; Salo, E.; Saxen, H.; Vaara, M.; Tarkka, E.; Peltola, H. Clinical “Pneumococcal Pneumonia” Due to Moraxella osloensis: Case Report and a Review. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, 625–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Camarasa, C.; Fernández-Parra, J.; Navarro-Marí, J.M.; Gutiérrez-Fernández, J. Moraxella osloensis emerging infection. Visiting to genital infection. Rev. Esp. Quim. 2018, 31, 178–181. [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama, Y.; Shigemura, T.; Aoyama, K.; Nagano, N.; Nakazawa, Y. Bacteremia Due to Moraxella osloensis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 22, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, A.; Kasahara, K.; Ogawa, Y.; Samejima, K.; Eriguchi, M.; Yano, H.; Mikasa, K.; Tsuruya, K. Peritonitis Due to Moraxella osloensis: A Case Report and Literature Review. J. Infect. Chemother. 2019, 25, 1050–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kim, M.; Lee, W.; Kang, S. Bacteremia Caused by Moraxella osloensis: A Fatal Case of an Immunocompromised Patient and Literature Review. Clin. Lab. 2021, 67, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabbuso, T.; Defourny, L.; Lali, S.E.; Pasdermadjian, S.; Gilliaux, O. Moraxella osloensis Infection among Adults and Children: A Pediatric Case and Literature Review. Arch. Pédiatrie 2021, 28, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Xia, J.; Jiang, L.; Tan, Y.; An, Y.; Zhu, X.; Ruan, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhen, H.; Ma, Y.; et al. Characterization of the Human Skin Resistome and Identification of Two Microbiota Cutotypes. Microbiome 2021, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, K.; Saeki, T.; Arikawa, K.; Yoda, T.; Endoh, T.; Matsuhashi, A.; Takeyama, H.; Hosokawa, M. Exploring Strain Diversity of Dominant Human Skin Bacterial Species Using Single-Cell Genome Sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 955404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Li, Z.; Zhong, Q.; Wei, Q.; Jiang, L.; Duan, C.; Jia, H.; Tan, Y.; Han, L.; Wang, J.; et al. Integration of Skin Phenome and Microbiome Reveals the key Role of Bacteria in Human Skin Agin. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işeri, L.; Apan, T.; Şahin, E. The Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Moraxella Species Other Than Moraxella Catarrhalis. Turk. Klin. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 35, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ganzorig, M.; Lim, J.Y.; Hwang, I.; Lee, K. Complete Genome Sequence of Multidrug-Resistant Moraxella osloensis NP7 with Multiple Plasmids Isolated from Human Skin. Microbiol. Soc. Korea 2018, 54, 286–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi Ghaffoori Kanaan, M.; Riyadh Al-abodi, H.; Saad Abdullah, S.; Memariani, M.; Kohansal, M.; Ghasemian, A. Biofilm Formation and Drug Resistance Determinants of Moraxella Catarrhalis, Moraxella osloensis and Moraxella Lacunata from Clinical Samples in Iraq. Health Biotechnol. Biopharma (HBB) 2024, 7, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.; Hänsch, G.M. Pathophysiologie der implantatassoziierten Infektion. Orthopäde 2015, 44, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustyniak, D.; Seredyński, R.; McClean, S.; Roszkowiak, J.; Roszniowski, B.; Smith, D.L.; Drulis-Kawa, Z.; Mackiewicz, P. Virulence Factors of Moraxella Catarrhalis Outer Membrane Vesicles Are Major Targets for Cross-Reactive Antibodies and Have Adapted during Evolution. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| OD Value | Adhesion | Biofilm Production |

|---|---|---|

| OD ≤ ODc | Not adherent | Biofilm not producer |

| ODc < OD ≤ 2xODc | Weakly adherent | |

| 2xODc < OD ≤ 4xODc | Moderately adherent | Biofilm producer |

| 4xODc < OD | Strongly adherent |

| Strain | Antimicrobial Drugs (MICs as µg/mL) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | AMC | CFT | CIP | CFP | ERY | TET | TMP/SMX | |

| 1 | 0.023 | ≤0.016 | 0.004 | 0.032 | ≤0.016 | 0.38 | 1.5 | 0.064 |

| 2 | 0.032 | ≤0.016 | 0.004 | 0.19 | ≤0.016 | 0.75 | 1.5 | 0.125 |

| 3 | 0.19 | ≤0.016 | 0.016 | 0.094 | 0.032 | 0.38 | 0.75 | 0.094 |

| 4 | 0.094 | ≤0.016 | 0.032 | 0.125 | ≤0.016 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.19 |

| 5 | 0.094 | ≤0.016 | 0.012 | 0.016 | ≤0.016 | 0.125 | 1.5 | 0.125 |

| Strain | OD (Mean ± SD) | Biofilm Production |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.169 ± 0.047 | Not detected |

| 2 | 0.220 ± 0.149 | Not detected |

| 3 | 0.199 ± 0.121 | Not detected |

| 4 | 0.324 ± 0.166 | Detected |

| 5 | 0.546 ± 0.075 | Detected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bellato, E.; Longo, F.; Menotti, F.; Pagano, C.; Curtoni, A.; Bondi, A.; Castoldi, F.; Banche, G.; Allizond, V. Moraxella osloensis Isolated from the Intraoperative Field After Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2699. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122699

Bellato E, Longo F, Menotti F, Pagano C, Curtoni A, Bondi A, Castoldi F, Banche G, Allizond V. Moraxella osloensis Isolated from the Intraoperative Field After Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2699. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122699

Chicago/Turabian StyleBellato, Enrico, Fabio Longo, Francesca Menotti, Claudia Pagano, Antonio Curtoni, Alessandro Bondi, Filippo Castoldi, Giuliana Banche, and Valeria Allizond. 2025. "Moraxella osloensis Isolated from the Intraoperative Field After Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2699. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122699

APA StyleBellato, E., Longo, F., Menotti, F., Pagano, C., Curtoni, A., Bondi, A., Castoldi, F., Banche, G., & Allizond, V. (2025). Moraxella osloensis Isolated from the Intraoperative Field After Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2699. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122699