Recent Advances in the Role of Bacteriophages in the Aetiology and Therapy of Vaginal Dysbiosis in the Form of Bacterial Vaginosis and the Prevention of Preterm Birth

Abstract

1. Background

The Importance of Bacteriophages

2. Vaginal Eubiosis and Dysbiosis

2.1. Vaginal Eubiosis

2.2. Vaginal Dysbiosis

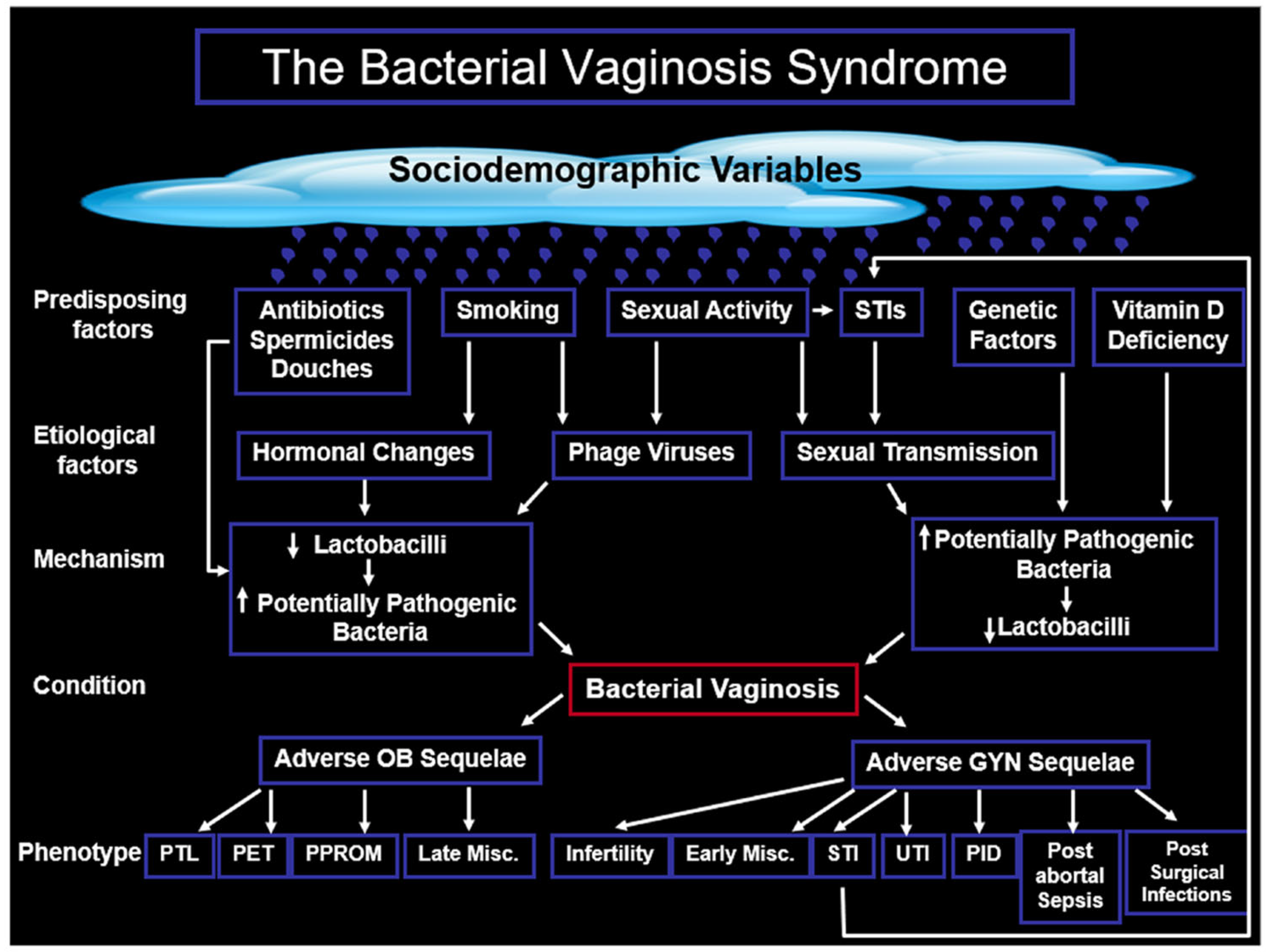

3. Bacterial Vaginosis

3.1. The Importance of BV

3.2. The Microbiology of Bacterial Vaginosis

3.3. Communication Between the Gut and the Vaginal Microbiome

3.4. The Biochemistry of Bacterial Vaginosis

3.5. Molecular Methods of Diagnosing Bacterial Vaginosis

3.6. Sexual Association or Sexual Transmission of BV

4. The Role of Bacteriophages in the Aetiology of Bacterial Vaginosis

4.1. Potential Beneficial Effects of Bacteriophages

4.2. Bacteriophage Protection of Lactobacillus spp.

5. Cost of Preterm Birth

5.1. The Importance of Preterm Birth

5.2. The Human Impact of PTB at the Extremes of Viability

5.3. The Financial Cost of PTB

5.4. The Psychosocial Cost of PTB

5.5. The Aetiology of Preterm Birth

6. The Prediction and Prevention of Preterm Birth

6.1. Bacterial Vaginosis in the Prediction of Preterm Birth

6.2. Treatment of BV in the Prevention of PTB

7. Bacteriophages in the Treatment of Bacterial Vaginosis and the Prevention of Preterm Birth

7.1. The Vaginal Virome

7.2. The Vaginal Virome in Health and Disease

7.2.1. The Indirect Role of Phages in Preterm Birth

7.2.2. Phage Viruses in Infertility

7.2.3. Viruses in Cervical Cancer

8. Therapeutic Interventions to Induce Vaginal Eubiosis

8.1. Probiotics

8.2. Antibiofilm Agents

8.3. Oleic Acid Treatment

8.4. Phage Lysins

8.5. Vaginal Microbiota Transplantation

9. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| BV | Bacterial vaginosis |

| BVAB | Bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria |

| CDC | Centres for disease control |

| CE-IVD | Conformité Européenne—in vitro diagnostic |

| CI | Confidence intervals |

| CST | Community state types |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FMT | Faecal microbiome transplantation |

| GAIN(Act) | Generating Antibiotic Innovation Now |

| GBS | Group B streptococcus |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HMP | Human microbiome project |

| HPV | Human papilloma virus |

| HR-HPV | High-risk human papilloma virus |

| HSV | Herpes simplex virus |

| IOM | Institute of Medicine |

| IUCD | Intrauterine contraceptive device |

| LM | Late miscarriage |

| MGD | Millenium development goals |

| MoD | March of Dimes |

| NSV | Non-specific vaginitis |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PPROM | Preterm prelabour rupture of the membranes |

| PTB | Preterm birth |

| SPTL | Spontaneous preterm labour |

| Preterm | Labour |

| STI | Sexually transmitted infections |

| VMT | Vaginal microbiome transplantation |

| WSW | Women who have sex with women |

References

- Gasanov, U.; Hughes, D.; Hansbro, P.M. Methods for the isolation and identification of Listeria spp. and Listeria monocytogenes: A review. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 851–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, W.C. Bacteriophage therapy. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001, 55, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górski, A.; Miedzybrodzki, R.; Borysowski, J.; Weber-Dabrowska, B.; Lobocka, M.; Fortuna, W.; Letkiewicz, S.; Zimecki, M.; Filby, G. Bacteriophage therapy for the treatment of infections. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2009, 10, 766–774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Principi, N.; Silvestri, E.; Esposito, S. Advantages and Limitations of Bacteriophages for the Treatment of Bacterial Infections. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.; Romero, E.; Garrido-Sanchez, L.; Alcaín-Martínez, G.; Andrade, R.J.; Taminiau, B.; Daube, G.; García-Fuentes, E. Microbiota Insights in Clostridium Difficile Infection and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1725220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wang, C.; Zhou, X.; Guo, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhao, R.; Song, H. Bacteriophage therapy for drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1336821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C. Where will new antibiotics come from? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2003, 1, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brives, C.; Pourraz, J. Phage therapy as a potential solution in the fight against AMR: Obstacles and possible futures. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirnay, J.P. Phage Therapy in the Year 2035. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swidsinski, A.; Guschin, A.; Corsini, L.; Loening-Baucke, V.; Tisakova, L.P.; Swidsinski, S.; Sobel, J.D.; Dörffel, Y. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Microbiota in Bacterial Vaginosis Using Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization. Pathogens 2022, 11, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swidsinski, A.; Amann, R.; Guschin, A.; Swidsinski, S.; Loening-Baucke, V.; Mendling, W.; Sobel, J.D.; Lamont, R.F.; Vaneechoutte, M.; Baptista, P.V.; et al. Polymicrobial consortia in the pathogenesis of biofilm vaginosis visualized by FISH. Historic review outlining the basic principles of the polymicrobial infection theory. Microbes Infect. 2024, 26, 105403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Jørgensen, J.S.; Lamont, R.F. The contribution of bacteriophages to the aetiology and treatment of the bacterial vaginosis syndrome. Fac. Rev. 2022, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Hamady, M.; Fraser-Liggett, C.M.; Knight, R.; Gordon, J.I. The human microbiome project. Nature 2007, 449, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraf, V.S.; Sheikh, S.A.; Ahmad, A.; Gillevet, P.M.; Bokhari, H.; Javed, S. Vaginal microbiome: Normalcy vs dysbiosis. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 3793–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, W.J.Y.; Chew, S.Y.; Than, L.T.L. Vaginal microbiota and the potential of Lactobacillus derivatives in maintaining vaginal health. Microb. Cell Fact. 2020, 19, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendharkar, S.; Skafte-Holm, A.; Simsek, G.; Haahr, T. Lactobacilli and Their Probiotic Effects in the Vagina of Reproductive Age Women. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heczko, P.B.; Giemza, M.; Ponikiewska, W.; Strus, M. Importance of Lactobacilli for Human Health. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Lopez, V.; Cook, R.L.; Sobel, J.D. Emerging role of lactobacilli in the control and maintenance of the vaginal bacterial microflora. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1990, 12, 856–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, R.F.; Sobel, J.D.; Akins, R.A.; Hassan, S.S.; Chaiworapongsa, T.; Kusanovic, J.P.; Romero, R. The vaginal microbiome: New information about genital tract flora using molecular based techniques. BJOG 2011, 118, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravel, J.; Gajer, P.; Abdo, Z.; Schneider, G.M.; Koenig, S.S.; McCulle, S.L.; Karlebach, S.; Gorle, R.; Russell, J.; Tacket, C.O.; et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 108 (Suppl. S1), 4680–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouioui, I.; Carro, L.; García-López, M.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Woyke, T.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Pukall, R.; Klenk, H.P.; Goodfellow, M.; Göker, M. Genome-Based Taxonomic Classification of the Phylum Actinobacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, L.M.; Marroquin, S.M.; Thorstenson, J.C.; Joyce, L.R.; Fuentes, E.J.; Doran, K.S.; Horswill, A.R. Genome-wide mutagenesis identifies factors involved in MRSA vaginal colonization. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.F.; Hua, C.Z.; Sun, L.Y.; Chao, F.; Zhou, M.M. Microbiological Findings of Symptomatic Vulvovaginitis in Chinese Prepubertal Girls. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2021, 34, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhuri, M.; Chatterjee, B.D.; Banerjee, M. A clinicobacteriological study on leucorrhoea. J. Indian Med. Assoc. 1998, 96, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lamont, R.F.; van den Munckhof, E.H.; Luef, B.M.; Vinter, C.A.; Jørgensen, J.S. Recent advances in cultivation-independent molecular-based techniques for the characterization of vaginal eubiosis and dysbiosis. Fac. Rev. 2020, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocomazzi, G.; De Stefani, S.; Del Pup, L.; Palini, S.; Buccheri, M.; Primiterra, M.; Sciannamè, N.; Faioli, R.; Maglione, A.; Baldini, G.M.; et al. The Impact of the Female Genital Microbiota on the Outcome of Assisted Reproduction Treatments. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntuli, L.; Mtshali, A.; Mzobe, G.; Liebenberg, L.J.; Ngcapu, S. Role of Immunity and Vaginal Microbiome in Clearance and Persistence of Human Papillomavirus Infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 927131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwebke, J.R. Gynecologic consequences of bacterial vaginosis. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2003, 30, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.R.; Duerr, A.; Pruithithada, N.; Rugpao, S.; Hillier, S.; Garcia, P.; Nelson, K. Bacterial vaginosis and HIV seroprevalence among female commercial sex workers in Chiang Mai, Thailand. AIDS 1995, 9, 1093–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.R.; Lingappa, J.R.; Baeten, J.M.; Ngayo, M.O.; Spiegel, C.A.; Hong, T.; Donnell, D.; Celum, C.; Kapiga, S.; Delany, S.; et al. Bacterial vaginosis associated with increased risk of female-to-male HIV-1 transmission: A prospective cohort analysis among African couples. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, R.F. Bacterial Vaginosis. In Preterm Birth; Critchley, H., Bennett, P., Thornton, S., Eds.; RCOG Press: London, UK, 2004; pp. 163–180. [Google Scholar]

- Piddock, L.J. The crisis of no new antibiotics—What is the way forward? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Workowski, K.A.; Bachmann, L.H.; Chan, P.A.; Johnston, C.M.; Muzny, C.A.; Park, I.; Reno, H.; Zenilman, J.M.; Bolan, G.A. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2021, 70, 1–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, H.L.; Dukes, C.D. Haemophilus vaginalis vaginitis: A newly defined specific infection previously classified non-specific vaginitis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1955, 69, 962–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vodstrcil, L.A.; Muzny, C.A.; Plummer, E.L.; Sobel, J.D.; Bradshaw, C.S. Bacterial vaginosis: Drivers of recurrence and challenges and opportunities in partner treatment. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabebe, E.; Anumba, D.O.C. Female Gut and Genital Tract Microbiota-Induced Crosstalk and Differential Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids on Immune Sequelae. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyn, L.A.; Krohn, M.A.; Hillier, S.L. Rectal colonization by group B Streptococcus as a predictor of vaginal colonization. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 201, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenchington, A.L.; Lamont, R.F. Group B streptococcal immunisation of pregnant women for the prevention of early and late onset Group B streptococcal infection of the neonate as well as adult disease. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2017, 16, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklaim, J.M.; Clemente, J.C.; Knight, R.; Gloor, G.B.; Reid, G. Changes in vaginal microbiota following antimicrobial and probiotic therapy. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2015, 26, 27799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, M.A.; Hawes, S.E.; Hillier, S.L. The identification of vaginal Lactobacillus species and the demographic and microbiologic characteristics of women colonized by these species. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 180, 1950–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachedjian, G.; Aldunate, M.; Bradshaw, C.S.; Cone, R.A. The role of lactic acid production by probiotic Lactobacillus species in vaginal health. Res. Microbiol. 2017, 168, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochu, H.N.; Zhang, Q.; Song, K.; Wang, L.; Deare, E.A.; Williams, J.D.; Icenhour, C.R.; Iyer, L.K. Characterization of vaginal microbiomes in clinician-collected bacterial vaginosis diagnosed samples. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0258224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osei Sekyere, J.; Oyenihi, A.B.; Trama, J.; Adelson, M.E. Species-Specific Analysis of Bacterial Vaginosis-Associated Bacteria. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0467622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, T.; Song, X.; Liao, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X. Best among the key molecular diagnostic markers of bacterial vaginosis. AMB Express 2025, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrazzo, J.M.; Koutsky, L.A.; Eschenbach, D.A.; Agnew, K.; Stine, K.; Hillier, S.L. Characterization of vaginal flora and bacterial vaginosis in women who have sex with women. J. Infect. Dis. 2002, 185, 1307–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzny, C.A.; Sobel, J.D. Bacterial Vaginosis—Time to Treat Male Partners. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1026–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodstrcil, L.A.; Plummer, E.L.; Fairley, C.K.; Hocking, J.S.; Law, M.G.; Petoumenos, K.; Bateson, D.; Murray, G.L.; Donovan, B.; Chow, E.P.F.; et al. Male-Partner Treatment to Prevent Recurrence of Bacterial Vaginosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, M.; Filardo, S.; Sessa, R. Cervicovaginal microbiota in Chlamydia trachomatis and other preventable sexually transmitted infections of public health importance: A systematic umbrella review. New Microbiol. 2025, 48, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Alisoltani, A.; Manhanzva, M.T.; Potgieter, M.; Balle, C.; Bell, L.; Ross, E.; Iranzadeh, A.; du Plessis, M.; Radzey, N.; McDonald, Z.; et al. Microbial function and genital inflammation in young South African women at high risk of HIV infection. Microbiome 2020, 8, 165, Correction in Microbiome, 2022, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.C.; Hart, A.L.; Kamm, M.A.; Stagg, A.J.; Knight, S.C. Mechanisms of action of probiotics: Recent advances. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villion, M.; Moineau, S. Bacteriophages of Lactobacillus. Front. Biosci. 2009, 14, 1661–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Wijgert, J.; Verwijs, M.C.; Agaba, S.K.; Bronowski, C.; Mwambarangwe, L.; Uwineza, M.; Lievens, E.; Nivoliez, A.; Ravel, J.; Darby, A.C. Intermittent Lactobacilli-containing Vaginal Probiotic or Metronidazole Use to Prevent Bacterial Vaginosis Recurrence: A Pilot Study Incorporating Microscopy and Sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, E.; Isenberg, H.D.; Alperstein, P.; France, K.; Borenstein, M.T. Ingestion of yogurt containing Lactobacillus acidophilus as prophylaxis for candidal vaginitis. Ann. Intern. Med. 1992, 116, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiliç, A.O.; Pavlova, S.I.; Ma, W.G.; Tao, L. Analysis of Lactobacillus phages and bacteriocins in American dairy products and characterization of a phage isolated from yogurt. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 2111–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlova, S.I.; Kiliç, A.O.; Mou, S.M.; Tao, L. Phage infection in vaginal lactobacilli: An in vitro study. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 5, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, R.R.; Haahr, T.; Humaidan, P.; Jensen, J.S.; Kot, W.P.; Castro-Mejia, J.L.; Deng, L.; Leser, T.D.; Nielsen, D.S. Characterization of the Vaginal DNA Virome in Health and Dysbiosis. Viruses 2020, 12, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklaim, J.M.; Gloor, G.B.; Anukam, K.C.; Cribby, S.; Reid, G. At the crossroads of vaginal health and disease, the genome sequence of Lactobacillus iners AB-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108 (Suppl. S1), 4688–4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verwijs, M.C.; Agaba, S.K.; Darby, A.C.; van de Wijgert, J. Impact of oral metronidazole treatment on the vaginal microbiota and correlates of treatment failure. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 157.E1–157.E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, A.L. Vaginal bacterial phaginosis? Sex. Transm. Infect. 1999, 75, 352–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, A.O.; Pavlova, S.I.; Alpay, S.; Kilic, S.S.; Tao, L. Comparative study of vaginal Lactobacillus phages isolated from women in the United States and Turkey: Prevalence, morphology, host range, and DNA homology. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2001, 8, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrazzo, J.M.; Antonio, M.; Agnew, K.; Hillier, S.L. Distribution of genital Lactobacillus strains shared by female sex partners. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 199, 680–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, S.I.; Tao, L. Induction of vaginal Lactobacillus phages by the cigarette smoke chemical benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide. Mutat. Res. 2000, 466, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on the Use of Phthalates as Excipients in Human Medicinal Products; European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kurilovich, E.; Geva-Zatorsky, N. Effects of bacteriophages on gut microbiome functionality. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2481178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garneau, J.E.; Moineau, S. Bacteriophages of lactic acid bacteria and their impact on milk fermentations. Microb. Cell Fact. 2011, 10 (Suppl. S1), S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federici, S.; Nobs, S.P.; Elinav, E. Phages and their potential to modulate the microbiome and immunity. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, J.; Slack, E.; Foster, K.R. Host control of the microbiome: Mechanisms, evolution, and disease. Science 2024, 385, eadi3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Ananthaswamy, N.; Jain, S.; Batra, H.; Tang, W.C.; Lewry, D.A.; Richards, M.L.; David, S.A.; Kilgore, P.B.; Sha, J.; et al. A Universal Bacteriophage T4 Nanoparticle Platform to Design Multiplex SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Candidates by CRISPR Engineering. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira-Baptista, P.; De Seta, F.; Verstraelen, H.; Ventolini, G.; Lonnee-Hoffmann, R.; Lev-Sagie, A. The Vaginal Microbiome: V. Therapeutic Modalities of Vaginal Microbiome Engineering and Research Challenges. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2022, 26, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, R.F. Spontaneous preterm labour that leads to preterm birth: An update and personal reflection. Placenta 2019, 79, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March of Dimes Foundation. March of Dimes White Paper on Preterm Birth: The Global and Regional Toll 2009 [updated 2009/12/16]. Available online: http://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/white-paper-on-preterm-birth.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Costeloe, K.; Hennessy, E.; Gibson, A.T.; Marlow, N.; Wilkinson, A.R. The EPICure study: Outcomes to discharge from hospital for infants born at the threshold of viability. Pediatrics 2000, 106, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellman, V.; Hellstrom-Westas, L.; Norman, M.; Westgren, M.; Kallen, K.; Lagercrantz, H.; Marsal, K.; Serenius, F.; Wennergren, M. One-year survival of extremely preterm infants after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA 2009, 301, 2225–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, S.; Abangma, G.; Johnson, S.; Wolke, D.; Marlow, N. Costs and Health Utilities Associated with Extremely Preterm Birth: Evidence from the EPICure Study. Value Health 2009, 12, 1124–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention; Behrman, R.E., Butler, A.S., Eds.; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lettieri, L.; Vintzileos, A.M.; Rodis, J.F.; Albini, S.M.; Salafia, C.M. Does “idiopathic” preterm labor resulting in preterm birth exist? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1993, 168, 1480–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.; McGregor, J.A.; French, J.I. Preterm birth is associated with increased risk of maternal and neonatal infection. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992, 79, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hay, P.E.; Lamont, R.F.; Taylor-Robinson, D.; Morgan, D.J.; Ison, C.; Pearson, J. Abnormal bacterial colonisation of the genital tract and subsequent preterm delivery and late miscarriage. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1994, 308, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, P.E.; Morgan, D.J.; Ison, C.A.; Bhide, S.A.; Romney, M.; McKenzie, P.; Pearson, J.; Lamont, R.F.; Taylor-Robinson, D. A longitudinal study of bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1994, 101, 1048–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamont, R.F. Advances in the Prevention of Infection-Related Preterm Birth. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstein, I.J.; Morgan, D.J.; Lamont, R.F.; Sheehan, M.; Dore, C.J.; Hay, P.E.; Taylor-Robinson, D. Effect of intravaginal clindamycin cream on pregnancy outcome and on abnormal vaginal microbial flora of pregnant women. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 8, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, R.F.; Nhan-Chang, C.L.; Sobel, J.D.; Workowski, K.; Conde-Agudelo, A.; Romero, R. Treatment of abnormal vaginal flora in early pregnancy with clindamycin for the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 205, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnstrom, O.; Olausson, P.O.; Sedin, G.; Serenius, F.; Svenningsen, N.; Thiringer, K.; Tunell, R.; Wennergren, M.; Wesstrom, G. The Swedish national prospective study on extremely low birthweight (ELBW) infants. Incidence, mortality, morbidity and survival in relation to level of care. Acta Paediatr. 1997, 86, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekki, M.; Kurki, T.; Pelkonen, J.; Kurkinen-Raty, M.; Cacciatore, B.; Paavonen, J. Vaginal clindamycin in preventing preterm birth and peripartal infections in asymptomatic women with bacterial vaginosis: A randomized, controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 97 Pt 1, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosmann, C.; Anahtar, M.N.; Handley, S.A.; Farcasanu, M.; Abu-Ali, G.; Bowman, B.A.; Padavattan, N.; Desai, C.; Droit, L.; Moodley, A.; et al. Lactobacillus-Deficient Cervicovaginal Bacterial Communities Are Associated with Increased HIV Acquisition in Young South African Women. Immunity 2017, 46, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Costa, A.C.; Moron, A.F.; Forney, L.J.; Linhares, I.M.; Sabino, E.; Costa, S.F.; Mendes-Correa, M.C.; Witkin, S.S. Identification of bacteriophages in the vagina of pregnant women: A descriptive study. BJOG 2021, 128, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.T.; Wang, H.; Wu, H.S.; Zeng, J.; Yang, Y. Comparison of viromes in vaginal secretion from pregnant women with and without vaginitis. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happel, A.U.; Balle, C.; Maust, B.S.; Konstantinus, I.N.; Gill, K.; Bekker, L.G.; Froissart, R.; Passmore, J.A.; Karaoz, U.; Varsani, A.; et al. Presence and Persistence of Putative Lytic and Temperate Bacteriophages in Vaginal Metagenomes from South African Adolescents. Viruses 2021, 13, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madere, F.S.; Sohn, M.; Winbush, A.K.; Barr, B.; Grier, A.; Palumbo, C.; Java, J.; Meiring, T.; Williamson, A.L.; Bekker, L.G.; et al. Transkingdom Analysis of the Female Reproductive Tract Reveals Bacteriophages form Communities. Viruses 2022, 14, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelin, E.A.; Skidmore, P.T.; Łaniewski, P.; Holland, L.A.; Chase, D.M.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M.M.; Lim, E.S. Cervicovaginal DNA Virome Alterations Are Associated with Genital Inflammation and Microbiota Composition. mSystems 2022, 7, e0006422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiao, L.; Xiao, B.; Zhang, B.; Zuo, Z.; Ji, P.; Zheng, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, F. Maternal and neonatal viromes indicate the risk of offspring’s gastrointestinal tract exposure to pathogenic viruses of vaginal origin during delivery. mLife 2022, 1, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cao, L.; Han, X.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhang, C. Altered vaginal eukaryotic virome is associated with different cervical disease status. Virol. Sin. 2023, 38, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, A.M.A.; Siqueira, J.D.; Curty, G.; Goes, L.R.; Policarpo, C.; Meyrelles, A.R.; Furtado, Y.; Almeida, G.; Giannini, A.L.M.; Machado, E.S.; et al. Microbiome analysis of Brazilian women cervix reveals specific bacterial abundance correlation to RIG-like receptor gene expression. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1147950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, A.C.; Bortoletto, P.; Spandorfer, S.D.; Tozetto-Mendoza, T.R.; Linhares, I.M.; Mendes-Correa, M.C.; Witkin, S.S. Association between torquetenovirus in vaginal secretions and infertility: An exploratory metagenomic analysis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2023, 90, e13788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugerth, L.W.; Krog, M.C.; Vomstein, K.; Du, J.; Bashir, Z.; Kaldhusdal, V.; Fransson, E.; Engstrand, L.; Nielsen, H.S.; Schuppe-Koistinen, I. Defining Vaginal Community Dynamics: Daily microbiome transitions, the role of menstruation, bacteriophages, and bacterial genes. Microbiome 2024, 12, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Jin, S.; Lv, O.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, W.; Long, F.; Shen, Z.; Bai, S.; et al. Comparative analysis of the vaginal bacteriome and virome in healthy women living in high-altitude and sea-level areas. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Guo, R.; Li, S.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, S.; Lv, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Kang, J.; Meng, J.; et al. A multi-kingdom collection of 33,804 reference genomes for the human vaginal microbiome. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 2185–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaelin, E.A.; Mitchell, C.; Soria, J.; Rosa, A.; Ticona, E.; Coombs, R.W.; Frenkel, L.M.; Bull, M.E.; Lim, E.S. Longitudinal cervicovaginal microbiome and virome alterations during ART and discordant shedding in women living with HIV. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orton, K.L.; Monaco, C.L. The Vaginal Virome in Women’s Health and Disease. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madere, F.S.; Monaco, C.L. The female reproductive tract virome: Understanding the dynamic role of viruses in gynecological health and disease. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2022, 52, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldor, M.K. Bacteriophage biology and bacterial virulence. Trends Microbiol. 1998, 6, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sausset, R.; Petit, M.A.; Gaboriau-Routhiau, V.; De Paepe, M. New insights into intestinal phages. Mucosal Immunol. 2020, 13, 205–215, Correction in Mucosal Immunol. 2020, 13, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Félix, J.; Villicaña, C. The impact of quorum sensing on the modulation of phage-host interactions. J. Bacteriol. 2021, 203, e00687-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erez, Z.; Steinberger-Levy, I.; Shamir, M.; Doron, S.; Stokar-Avihail, A.; Peleg, Y.; Melamed, S.; Leavitt, A.; Savidor, A.; Albeck, S.; et al. Communication between viruses guides lysis-lysogeny decisions. Nature 2017, 541, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damelin, L.H.; Paximadis, M.; Mavri-Damelin, D.; Birkhead, M.; Lewis, D.A.; Tiemessen, C.T. Identification of predominant culturable vaginal Lactobacillus species and associated bacteriophages from women with and without vaginal discharge syndrome in South Africa. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 60 Pt 2, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudnadottir, U.; Debelius, J.W.; Du, J.; Hugerth, L.W.; Danielsson, H.; Schuppe-Koistinen, I.; Fransson, E.; Brusselaers, N. The vaginal microbiome and the risk of preterm birth: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, K.M.; Wylie, T.N.; Cahill, A.G.; Macones, G.A.; Tuuli, M.G.; Stout, M.J. The vaginal eukaryotic DNA virome and preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 219, 189.E1–189.E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racicot, K.; Cardenas, I.; Wünsche, V.; Aldo, P.; Guller, S.; Means, R.E.; Romero, R.; Mor, G. Viral infection of the pregnant cervix predisposes to ascending bacterial infection. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardenas, I.; Means, R.E.; Aldo, P.; Koga, K.; Lang, S.M.; Booth, C.J.; Manzur, A.; Oyarzun, E.; Romero, R.; Mor, G. Viral infection of the placenta leads to fetal inflammation and sensitization to bacterial products predisposing to preterm labor. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 1248–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, E.B.; Pinto, A.R.; Fongaro, G. Bacteriophages as Potential Clinical Immune Modulators. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogokhia, L.; Round, J.L. Immune-bacteriophage interactions in inflammatory bowel diseases. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2021, 49, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champagne-Jorgensen, K.; Luong, T.; Darby, T.; Roach, D.R. Immunogenicity of bacteriophages. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 1058–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Belleghem, J.D.; Dąbrowska, K.; Vaneechoutte, M.; Barr, J.J.; Bollyky, P.L. Interactions between Bacteriophage, Bacteria, and the Mammalian Immune System. Viruses 2018, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fettweis, J.M.; Serrano, M.G.; Brooks, J.P.; Edwards, D.J.; Girerd, P.H.; Parikh, H.I.; Huang, B.; Arodz, T.J.; Edupuganti, L.; Glascock, A.L.; et al. The vaginal microbiome and preterm birth. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroven, K.; Aertsen, A.; Lavigne, R. Bacteriophages as drivers of bacterial virulence and their potential for biotechnological exploitation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 45, fuaa041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskew, A.M.; Stout, M.J.; Bedrick, B.S.; Riley, J.K.; Omurtag, K.R.; Jimenez, P.T.; Odem, R.R.; Ratts, V.S.; Keller, S.L.; Jungheim, E.S.; et al. Association of the eukaryotic vaginal virome with prophylactic antibiotic exposure and reproductive outcomes in a subfertile population undergoing in vitro fertilisation: A prospective exploratory study. BJOG 2020, 127, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosado-Rodríguez, E.; Alvarado-Vélez, I.; Romaguera, J.; Godoy-Vitorino, F. Vaginal Microbiota and HPV in Latin America: A Narrative Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, E.; Milani, A.; Seyedinkhorasani, M.; Bolhassani, A. HPV co-infections with other pathogens in cancer development: A comprehensive review. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e29236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebeau, A.; Bruyere, D.; Roncarati, P.; Peixoto, P.; Hervouet, E.; Cobraiville, G.; Taminiau, B.; Masson, M.; Gallego, C.; Mazzucchelli, G.; et al. HPV infection alters vaginal microbiome through down-regulating host mucosal innate peptides used by Lactobacilli as amino acid sources. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolò, S.; Antonelli, A.; Tanturli, M.; Baccani, I.; Bonaiuto, C.; Castronovo, G.; Rossolini, G.M.; Mattiuz, G.; Torcia, M.G. Bacterial Species from Vaginal Microbiota Differently Affect the Production of the E6 and E7 Oncoproteins and of p53 and p-Rb Oncosuppressors in HPV16-Infected Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Gu, Y.; Xian, Y.; Li, Q.; He, Y.; Chen, K.; Yu, H.; Deng, H.; Xiong, L.; Cui, Z.; et al. Efficacy and safety of different drugs for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1402346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, M.A.; Meyn, L.A.; Murray, P.J.; Busse, B.; Hillier, S.L. Vaginal colonization by probiotic Lactobacillus crispatus CTV-05 is decreased by sexual activity and endogenous Lactobacilli. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 199, 1506–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngugi, B.M.; Hemmerling, A.; Bukusi, E.A.; Kikuvi, G.; Gikunju, J.; Shiboski, S.; Fredricks, D.N.; Cohen, C.R. Effects of bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria and sexual intercourse on vaginal colonization with the probiotic Lactobacillus crispatus CTV-05. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2011, 38, 1020–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Wang, W.; Su, Y.; Sun, W.; Ma, L. Antibiotics therapy combined with probiotics administered intravaginally for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Med. 2023, 18, 20230644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abavisani, M.; Sahebi, S.; Dadgar, F.; Peikfalak, F.; Keikha, M. The role of probiotics as adjunct treatment in the prevention and management of gynecological infections: An updated meta-analysis of 35 RCT studies. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 63, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, F.; Chen, J.; Luo, J.; Wu, C.; Chen, T. Effectiveness of vaginal probiotics Lactobacillus crispatus chen-01 in women with high-risk HPV infection: A prospective controlled pilot study. Aging 2024, 16, 11446–11459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, K.; Wooten, D.; Annepally, S.; Burke, L.; Edi, R.; Morris, S.R. Impact of (recurrent) bacterial vaginosis on quality of life and the need for accessible alternative treatments. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, A.; Parvaiz, F.; Manzoor, S. Bacterial vaginosis: An insight into the prevalence, alternative treatments regimen and it’s associated resistance patterns. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 127, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Manos, J.; Whiteley, G.; Zablotska-Manos, I. Antibiofilm Agents for the Treatment and Prevention of Bacterial Vaginosis: A Systematic Narrative Review. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 230, e508–e517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, J.; Sousa, L.G.V.; França, Â.; Podpera Tisakova, L.; Corsini, L.; Cerca, N. Exploiting the Anti-Biofilm Effect of the Engineered Phage Endolysin PM-477 to Disrupt In Vitro Single- and Dual-Species Biofilms of Vaginal Pathogens Associated with Bacterial Vaginosis. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.G.V.; Pereira, S.A.; Cerca, N. Fighting polymicrobial biofilms in bacterial vaginosis. Microb. Biotechnol. 2023, 16, 1423–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Frank, M.W.; Radka, C.D.; Jeanfavre, S.; Xu, J.; Tse, M.W.; Pacheco, J.A.; Kim, J.S.; Pierce, K.; Deik, A.; et al. Vaginal Lactobacillus fatty acid response mechanisms reveal a metabolite-targeted strategy for bacterial vaginosis treatment. Cell 2024, 187, 5413–5430.E29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischetti, V.A. Novel method to control pathogenic bacteria on human mucous membranes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003, 987, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, A.; Diene, S.M.; Courtier-Martinez, L.; Gaillard, J.B.; Gbaguidi-Haore, H.; Mereghetti, L.; Quentin, R.; Francois, P.; Van Der Mee-Marquet, N. 12/111phiA Prophage Domestication Is Associated with Autoaggregation and Increased Ability to Produce Biofilm in Streptococcus agalactiae. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocanova, L.; Psenko, M.; Barák, I.; Halgasova, N.; Drahovska, H.; Bukovska, G. A novel phage-encoded endolysin EN534-C active against clinical strain Streptococcus agalactiae GBS. J. Biotechnol. 2022, 359, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yockey, L.J.; Hussain, F.A.; Bergerat, A.; Reissis, A.; Worrall, D.; Xu, J.; Gomez, I.; Bloom, S.M.; Mafunda, N.A.; Kelly, J.; et al. Screening and characterization of vaginal fluid donations for vaginal microbiota transplantation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, G. Vaginal microbiota transplantation is a truly opulent and promising edge: Fully grasp its potential. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1280636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuniyazi, M.; Zhang, N. Possible Therapeutic Mechanisms and Future Perspectives of Vaginal Microbiota Transplantation. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadegar, A.; Bar-Yoseph, H.; Monaghan, T.M.; Pakpour, S.; Severino, A.; Kuijper, E.J.; Smits, W.K.; Terveer, E.M.; Neupane, S.; Nabavi-Rad, A.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation: Current challenges and future landscapes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 37, e0006022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, V.; Vincent, C.; Edens, T.J.; Miller, M.; Manges, A.R. Antimicrobial Resistance Gene Acquisition and Depletion Following Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2018, 66, 456–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFilipp, Z.; Bloom, P.P.; Torres Soto, M.; Mansour, M.K.; Sater, M.R.A.; Huntley, M.H.; Turbett, S.; Chung, R.T.; Chen, Y.B.; Hohmann, E.L. Drug-Resistant E. coli Bacteremia Transmitted by Fecal Microbiota Transplant. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2043–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happel, A.U.; Kullin, B.R.; Gamieldien, H.; Jaspan, H.B.; Varsani, A.; Martin, D.; Passmore, J.S.; Froissart, R. In Silico Characterisation of Putative Prophages in Lactobacillaceae Used in Probiotics for Vaginal Health. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, J.; Zborowsky, S.; Debarbieux, L.; Weitz, J.S. The dynamic interplay of bacteriophage, bacteria and the mammalian host during phage therapy. iScience 2023, 26, 106004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliken, S.; Allen, R.M.; Lamont, R.F. The Role of Antimicrobial Treatment During Pregnancy on the Neonatal Gut Microbiome and the Development of Atopy, Asthma, Allergy and Obesity in Childhood. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2019, 18, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furfaro, L.L.; Chang, B.J.; Payne, M.S. Applications for Bacteriophage Therapy during Pregnancy and the Perinatal Period. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NuSwab ** | SureSwab | BD MAX Vaginal Panel *** | MDL BV Panel | AmpliSens * | Hologic Aptima BV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Predictors of BV | ||||||

| Atopobium vaginae # | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Gardnerella vaginalis | − | + | + | + | + * | + |

| Megasphaera spp. (types 1 or 2) | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| BVAB-2 ## | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| Negative Predictors of BV | ||||||

| Lactobacillus acidophilus | − | + | _ | − | * | − |

| Lactobacillus crispatus | + | + | + | − | * | + |

| Lactobacillus jensenii | − | + | + | − | * | + |

| Lactobacillus gasseri | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Region | Number of PTBs Annually | PTB Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Asia | 6,907,000 | 9.1 |

| Africa | 4,047,000 | 11.9 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | 933,000 | 8.1 |

| North America | 480,000 | 10.6 |

| Europe | 466,000 | 6.2 |

| Oceania | 20,000 | 6.4 |

| World Total | 12,870,000 | 9.6 |

| (a) | ||||||

| Outcome | 22 w | 23 w | 24 w | 25 w | 26 w | Total |

| Delivery Room Death | 55% | 16% | 6.9% | 2% | 0% | 8.2% |

| Early NND (<7 d) | 80% | 39% | 21% | 11% | 9.2% | 22% |

| NND (<28 d) | 88% | 46% | 29% | 14% | 13% | 26% |

| Infant Death (0–365 d) | 90% | 48% | 33% | 19% | 15% | 30% |

| (b) | ||||||

| Morbidity | 22 w | 23 w | 24 w | 25 w | 26 w | Total |

| IVH (>grade 2) | 20% | 19% | 10% | 12% | 5.2% | 10% |

| ROP (>grade 2) | 80% | 62% | 48% | 32% | 19% | 34% |

| Severe BPD | 40% | 26% | 31% | 29% | 17% | 25% |

| PVL | 0% | 9.4% | 6.2% | 5.4% | 4.5% | 5.6% |

| NEC | 0% | 1.9% | 9.4% | 6.0% | 5.1% | 5.8% |

| No Major Morbidity @ 365 days | 2% | 8.9% | 21% | 37% | 54% | 32% |

| Factors | % |

|---|---|

| Faulty placentation | 50 |

| Intrauterine infection | 38 |

| Immunological factors | 30 |

| Cervical incompetence | 16 |

| Uterine factors | 14 |

| Maternal factors | 10 |

| Trauma and surgery | 8 |

| Foetal anomalies | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lamont, R.F.; Ali, A.; Jørgensen, J.S. Recent Advances in the Role of Bacteriophages in the Aetiology and Therapy of Vaginal Dysbiosis in the Form of Bacterial Vaginosis and the Prevention of Preterm Birth. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102410

Lamont RF, Ali A, Jørgensen JS. Recent Advances in the Role of Bacteriophages in the Aetiology and Therapy of Vaginal Dysbiosis in the Form of Bacterial Vaginosis and the Prevention of Preterm Birth. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(10):2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102410

Chicago/Turabian StyleLamont, Ronald F., Amaan Ali, and Jan Stener Jørgensen. 2025. "Recent Advances in the Role of Bacteriophages in the Aetiology and Therapy of Vaginal Dysbiosis in the Form of Bacterial Vaginosis and the Prevention of Preterm Birth" Microorganisms 13, no. 10: 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102410

APA StyleLamont, R. F., Ali, A., & Jørgensen, J. S. (2025). Recent Advances in the Role of Bacteriophages in the Aetiology and Therapy of Vaginal Dysbiosis in the Form of Bacterial Vaginosis and the Prevention of Preterm Birth. Microorganisms, 13(10), 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102410