Distinct Gut and Skin Microbiomes of a Carnivorous Caecilian Larva (Ichthyophis bannanicus) Show Ecological and Phylogenetic Divergence from Anuran Tadpoles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification and Sequencing

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

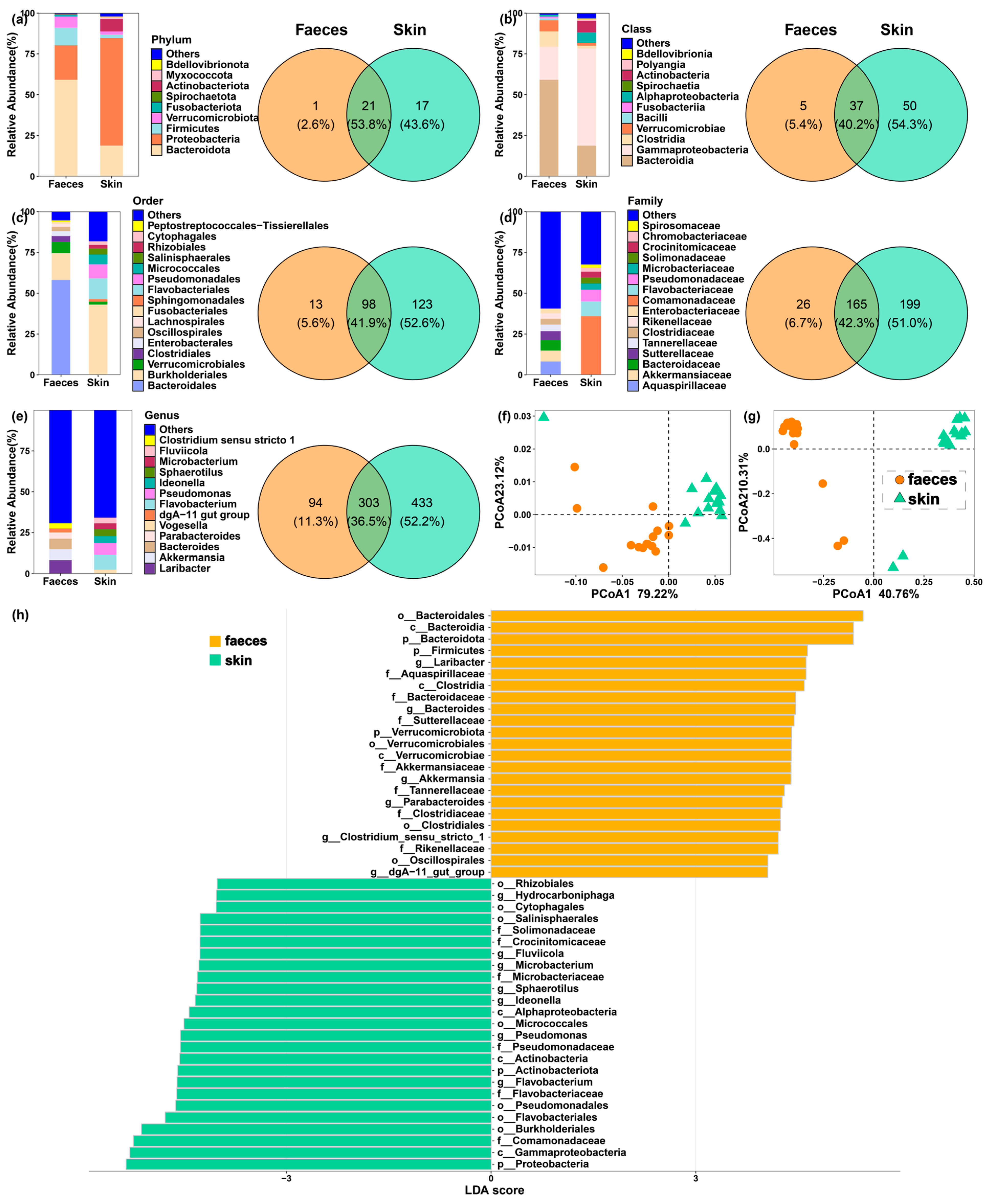

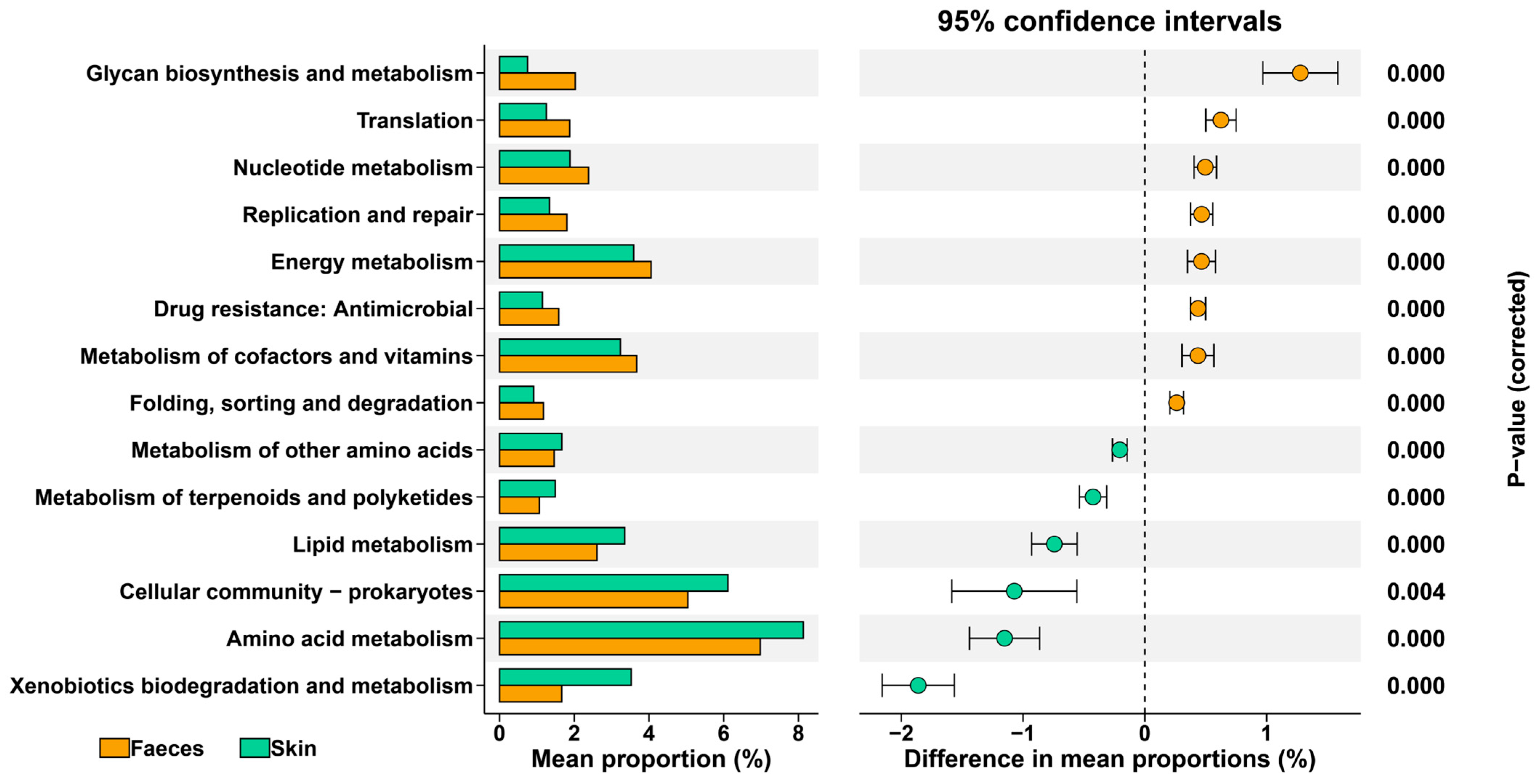

3.1. Distinct Gut and Skin Bacterial Communities in I. bannanicus

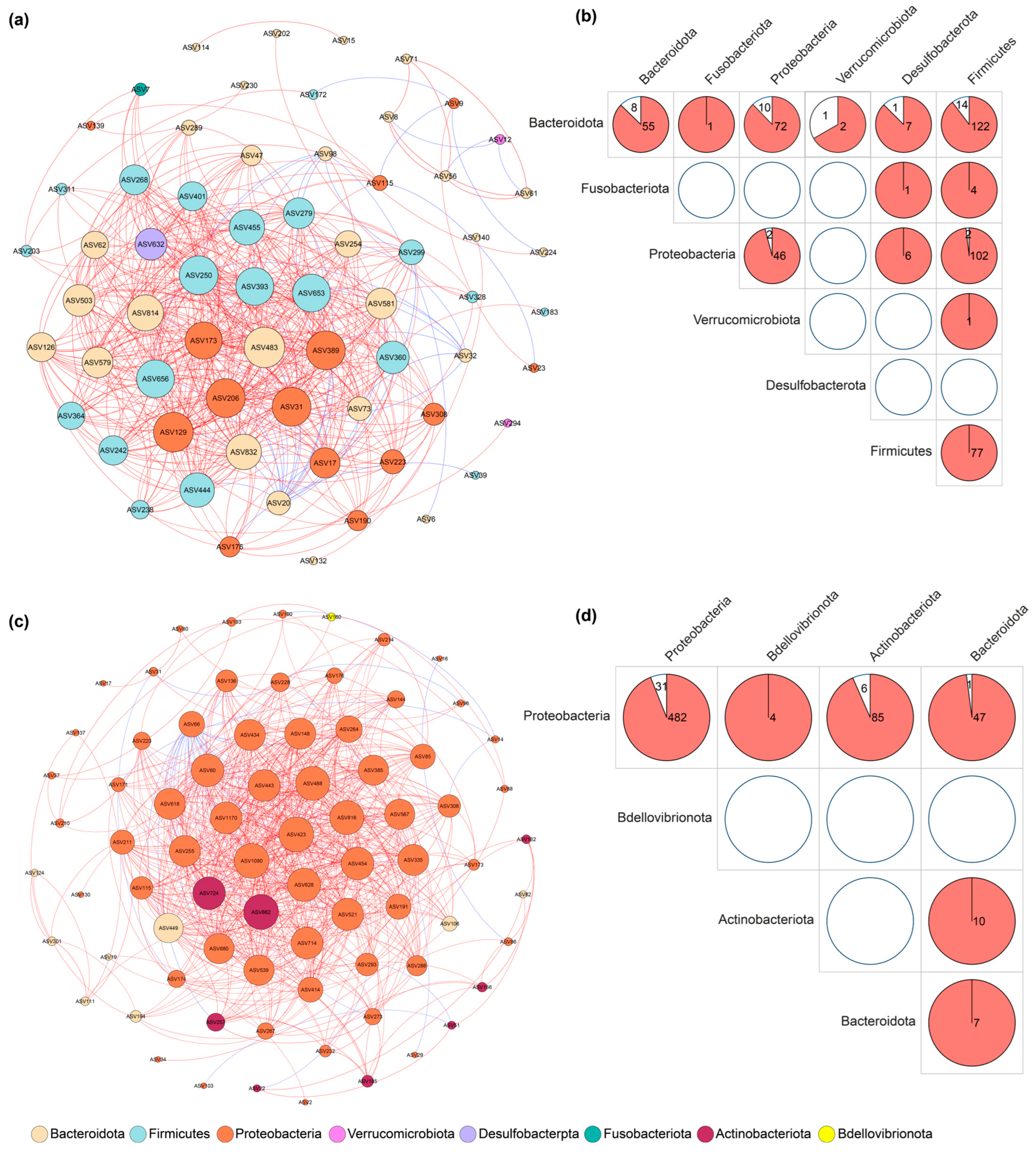

3.2. Core Microbiome and Co-Occurrence Networks

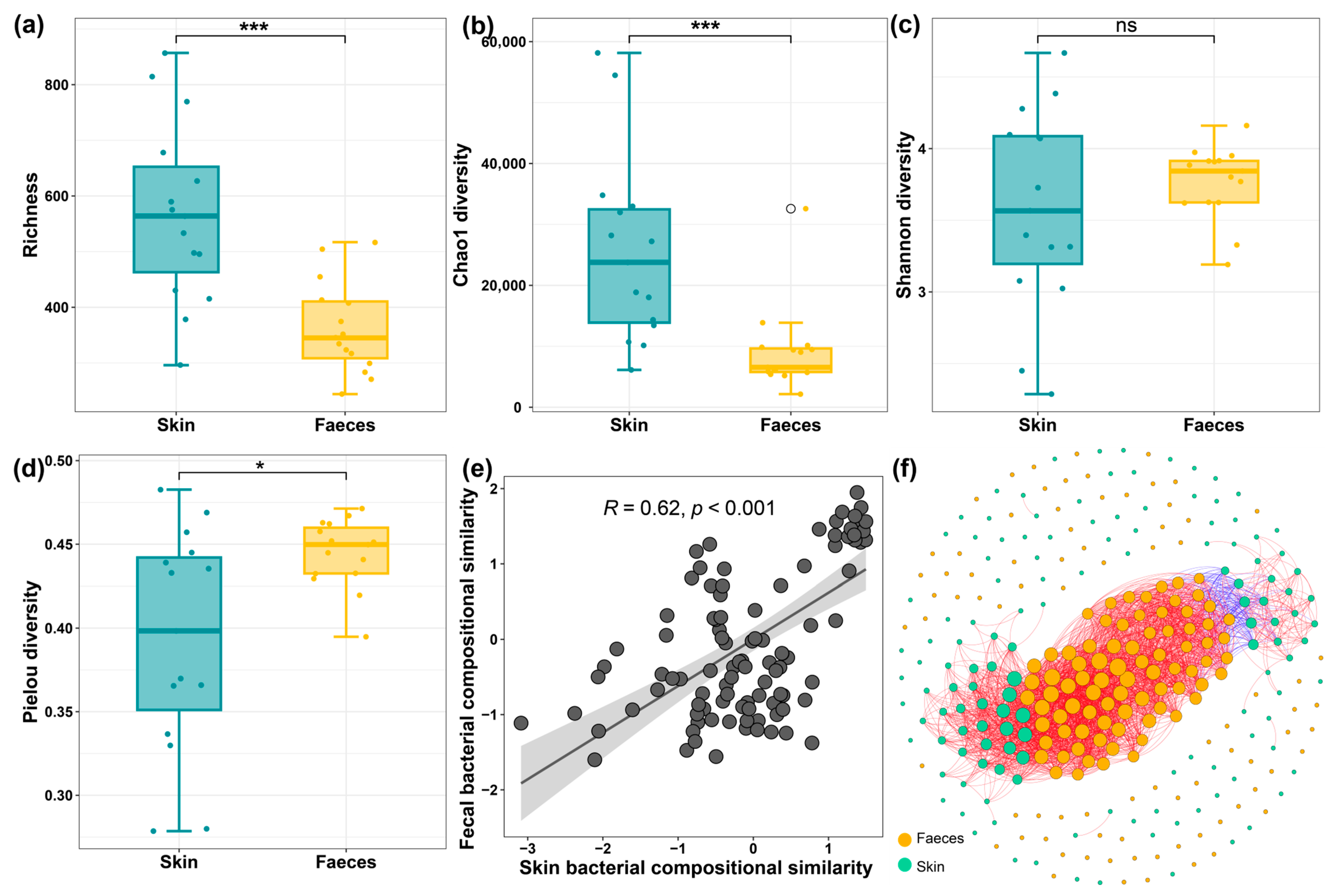

3.3. The Diversity of Skin and Faecal Microbiome and Their Relationships

3.4. Comparison with Anuran Larval Microbiomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.X.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, E.R.; Sanders, J.G.; Song, S.J.; Amato, K.R.; Clark, A.G.; Knight, R. The human microbiome in evolution. BMC Biol. 2017, 15, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanning, I.; Diaz-Sanchez, S. The functionality of the gastrointestinal microbiome in non-human animals. Microbiome 2015, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilbur, H.M. Complex life cycles. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1980, 11, 67–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duellman, W.E.; Trueb, L. Biology of Amphibians; John Hopkins Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, I.; Ramser, A.; Isham, N.; Ghannoum, M.A. The gut microbiome as a major regulator of the gut-skin axis. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kueneman, J.G.; Parfrey, L.W.; Woodhams, D.C.; Archer, H.M.; Knight, R.; McKenzie, V.J. The amphibian skin-associated microbiome across species, space and life history stages. Mol. Ecol. 2014, 23, 1238–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, R.R.; Sommer, S. The amphibian microbiome: Natural range of variation, pathogenic dysbiosis, and role in conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2017, 26, 763–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Herath, J.; Zhou, S.; Ellepola, G.; Meegaskumbura, M. Associations of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis with skin bacteria and fungi on Asian amphibian hosts. ISME Commun. 2023, 3, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.H. The Caecilians of the World: A Taxonomic Review; University of Kansas Press: Lawrence, KS, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Bei, Y.; Tan, Y.; Meng, S.; Xie, W.; Li, J. Observations of the reared caecilian, Ichthyophis bannanica. Sichuan J. Zool. 2010, 29, 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Luo, X.; Meng, S.; Bei, Y.; Song, T.; Meng, T.; Li, G.; Zhang, B. The phylogeography and population demography of the Yunnan caecilian (Ichthyophis bannanicus): Massive rivers as barriers to gene flow. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Long, J.; Xiang, J.; He, T.; Zhang, N.; Pan, W. Gut microbiota differences during metamorphosis in sick and healthy giant spiny frogs (Paa spinosa) tadpoles. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.A.; Rodrigues Hoffmann, A.; Neufeld, J.D. The skin microbiome of vertebrates. Microbiome 2019, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warne, R.W.; Kirschman, L.; Zeglin, L. Manipulation of gut microbiota reveals shifting community structure shaped by host developmental windows in amphibian larvae. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2017, 57, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bletz, M.C.; Goedbloed, D.J.; Sanchez, E.; Reinhardt, T.; Tebbe, C.C.; Bhuju, S.; Geffers, R.; Jarek, M.; Vences, M.; Steinfartz, S. Amphibian gut microbiota shifts differentially in community structure but converges on habitat-specific predicted functions. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebollar, E.A.; Martínez-Ugalde, E.; Orta, A.H. The amphibian skin microbiome and its protective role against chytridiomycosis. Herpetologica 2020, 76, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bletz, M.C.; Loudon, A.H.; Becker, M.H.; Bell, S.C.; Woodhams, D.C.; Minbiole, K.P.C.; Harris, R.N.; Gaillard, J.M. Mitigating amphibian chytridiomycosis with bioaugmentation: Characteristics of effective probiotics and strategies for their selection and use. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Chang, L.; Chang, Q.; Lu, G.; Jiang, J.; Zhu, L. The changes in the frog gut microbiome and its putative oxygen-related phenotypes accompanying the development of gastrointestinal complexity and dietary shift. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M.R.; Akter, S.; Tamanna, S.K.; Mazumder, L.; Esti, I.Z.; Banerjee, S.; Akter, S.; Hasan, M.R.; Acharjee, M.; Hossain, M.S.; et al. Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: Gut-skin axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, e2096995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, C.A.; Monteleone, G.; McLaughlin, J.T.; Paus, R. The gut-skin axis in health and disease: A paradigm with therapeutic implications. BioEssays 2016, 38, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.Q.; Dong, W.J.; Long, X.Z.; Yang, X.M.; Han, X.Y.; Kou, Y.H.; Tong, Q. Skin ulcers and microbiota in Rana dybowskii: Uncovering the role of the gut-skin axis in amphibian health. Aquaculture 2024, 585, 740724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; Hu, Z.F.; Du, X.P.; Bie, J.; Wang, H.B. Effects of seasonal hibernation on the similarities between the skin microbiota and gut microbiota of an amphibian (Rana dybowskii). Microb. Ecol. 2019, 79, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Subramanian, S.; Faith, J.J.; Gevers, D.; Gordon, J.I.; Knight, R.; Mills, D.A.; Caporaso, J.G. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C.; Haas, B.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Quince, C.; Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.; O’Hara, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.6-6.1. 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; Du, X.P.; Hu, Z.F.; Cui, L.Y.; Bie, J.; Zhang, Q.Z.; Xiao, J.H.; Lin, Y.; Wang, H.B. Comparison of the gut microbiota of Rana amurensis and Rana dybowskii under natural winter fasting conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2019, 366, fnz241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faust, K.; Sathirapongsasuti, J.F.; Izard, J.; Segata, N.; Gevers, D.; Raes, J.; Huttenhower, C. Microbial co-occurrence relationships in the human microbiome. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, e1002606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, M.; Heymann, S.; Jacomy, M. Gephi an Open Source Software for Exploring. 2009. Available online: https://gephi.org/publications/gephi-bastian-feb09.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Montoya, J.M.; Pimm, S.L.; Solé, R.V. Ecological networks and their fragility. Nature 2006, 442, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouete, M.T.; Bletz, M.C.; LaBumbard, B.C.; Woodhams, D.C.; Blackburn, D.C. Parental care contributes to vertical transmission of microbes in a skin-feeding and direct-developing caecilian. Anim. Microbiome 2023, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, K.A.; Friesen, J.; Loyau, A.; Butler, H.; Vredenburg, V.T.; Laufer, J.; Chatzinotas, A.; Schmeller, D.S. Environmental and anthropogenic factors shape the skin bacterial communities of a semi-arid amphibian species. Microb. Ecol. 2022, 86, 1393–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; Cui, L.Y.; Hu, Z.F.; Du, X.P.; Abid, H.M.; Wang, H.B. Environmental and host factors shaping the gut microbiota diversity of brown frog Rana dybowskii. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, J.M.; Bascompte, J.; Dupont, Y.L.; Jordano, P. The modularity of pollination networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19891–19896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szántó, M.; Dózsa, A.; Antal, D.; Szabó, K.; Kemény, L.; Bai, P. Targeting the gut-skin axis—Probiotics as new tools for skin disorder management? Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 1210–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Teng, J.L.L.; Que, T.-l.; Yung, R.W.H.; Luk, W.-k.; Lai, R.W.M.; Hui, W.-T.; Wong, S.S.Y.; Yau, H.-H.; et al. Association of Laribacter hongkongensis in community-acquired gastroenteritis with travel and eating fish: A multicentre case-control study. Lancet 2004, 363, 1941–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohl, K.D.; Cary, T.L.; Karasov, W.H.; Dearing, M.D. Restructuring of the amphibian gut microbiota through metamorphosis. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2013, 5, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Nelson, T.M.; Rodriguez Lopez, C.; Sarma, R.R.; Zhou, S.J.; Rollins, L.A. A comparison of nonlethal sampling methods for amphibian gut microbiome analyses. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Feature ID | Taxon | Relative Abundance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASV9 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Burkholderiales; f__Aquaspirillaceae; g__Laribacter | 7.71 | |

| ASV10 | p__Bacteroidota; c__Bacteroidia; o__Bacteroidales; f__Unclassified; g__Unclassified | 6.72 | |

| ASV12 | p__Verrucomicrobiota; c__Verrucomicrobiae; o__Verrucomicrobiales; f__Akkermansiaceae; g__Akkermansia | 6.25 | |

| ASV15 | p__Bacteroidota; c__Bacteroidia; o__Bacteroidales; f__Unclassified; g__Unclassified | 5.19 | |

| Faeces | ASV39 | p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Clostridiaceae; g__Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1 | 1.75 |

| ASV59 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Burkholderiales; f__Sutterellaceae; g__Unclassified | 1.07 | |

| ASV73 | p__Bacteroidota; c__Bacteroidia; o__Bacteroidales; f__Rikenellaceae; g__dgA-11_gut_group | 0.92 | |

| ASV90 | p__Bacteroidota; c__Bacteroidia; o__Bacteroidales; f__Tannerellaceae; g__Parabacteroides | 0.72 | |

| ASV114 | p__Bacteroidota; c__Bacteroidia; o__Bacteroidales; f__Unclassified; g__Unclassified | 0.58 | |

| ASV115 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Enterobacterales; f__Enterobacteriaceae; g__Escherichia-Shigella | 0.18 | |

| ASV254 | p__Bacteroidota; c__Bacteroidia; o__Bacteroidales; f__Bacteroidaceae; g__Bacteroides | 0.16 | |

| ASV268 | p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Oscillospirales; f__Butyricicoccaceae; g__Unclassified | 0.14 | |

| ASV6 | p__Bacteroidota; c__Bacteroidia; o__Flavobacteriales; f__Flavobacteriaceae; g__Flavobacterium | 8.7 | |

| ASV16 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Burkholderiales; f__Comamonadaceae; g__Unclassified | 3.82 | |

| ASV17 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Burkholderiales; f__Comamonadaceae; g__Ideonella | 4.06 | |

| ASV29 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Salinisphaerales;f__Solimonadaceae; g__Hydrocarboniphaga; g__Unclassified | 2.06 | |

| ASV49 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Burkholderiales; f__Comamonadaceae; g__Unclassified | 1.11 | |

| ASV103 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Alphaproteobacteria; o__Rhizobiales; f__Rhizobiaceae; g__Unclassified | 0.51 | |

| Skin | ASV115 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Enterobacterales; f__Enterobacteriaceae; g__Escherichia-Shigella | 0.25 |

| ASV124 | p__Bacteroidota; c__Bacteroidia; o__Cytophagales; f__Spirosomaceae; g__Emticicia | 0.48 | |

| ASV129 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Burkholderiales;f__Rhodocyclaceae; g__Methyloversatilis; g__Unclassified | 0.49 | |

| ASV136 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Pseudomonadales;f__Moraxellaceae; g__Perlucidibaca | 0.48 | |

| ASV137 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Salinisphaerales; f__Solimonadaceae; g__Nevskia | 0.37 | |

| ASV173 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Burkholderiales; f__Comamonadaceae; g__Paucibacter | 0.21 | |

| ASV174 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Alteromonadales; f__Alteromonadaceae; g__Rheinheimera | 0.28 | |

| ASV176 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Burkholderiales; f__Comamonadaceae; g__Acidovorax | 0.17 | |

| ASV228 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Alphaproteobacteria; o__Caulobacterales; f__Caulobacteraceae; g__Brevundimonas | 0.16 | |

| ASV255 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Burkholderiales; f__Comamonadaceae; g__Hydrogenophaga | 0.14 | |

| ASV293 | p__Proteobacteria; c__Alphaproteobacteria; o__Rhizobiales; f__Rhizobiaceae; g__Unclassified | 0.12 |

| Nodes | Edges | Average Degree | Average Path Length | Graph Diameter | Graph Density | Clustering Coefficient | Betweenness Centralization | Degree Centralization | Modularity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faeces | 79 | 303 | 7.6709 | 1.8680 | 5 | 0.0983 | 0.6218 | 0.0321 | 0.2863 | 0.2342 |

| Skin | 81 | 437 | 10.7901 | 3.2509 | 11 | 0.1349 | 0.8069 | 0.1145 | 0.2276 | 0.2521 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rajput, A.P.; Sun, D.; Zhou, S.; Meegaskumbura, M. Distinct Gut and Skin Microbiomes of a Carnivorous Caecilian Larva (Ichthyophis bannanicus) Show Ecological and Phylogenetic Divergence from Anuran Tadpoles. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2405. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102405

Rajput AP, Sun D, Zhou S, Meegaskumbura M. Distinct Gut and Skin Microbiomes of a Carnivorous Caecilian Larva (Ichthyophis bannanicus) Show Ecological and Phylogenetic Divergence from Anuran Tadpoles. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(10):2405. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102405

Chicago/Turabian StyleRajput, Amrapali Prithvisingh, Dan Sun, Shipeng Zhou, and Madhava Meegaskumbura. 2025. "Distinct Gut and Skin Microbiomes of a Carnivorous Caecilian Larva (Ichthyophis bannanicus) Show Ecological and Phylogenetic Divergence from Anuran Tadpoles" Microorganisms 13, no. 10: 2405. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102405

APA StyleRajput, A. P., Sun, D., Zhou, S., & Meegaskumbura, M. (2025). Distinct Gut and Skin Microbiomes of a Carnivorous Caecilian Larva (Ichthyophis bannanicus) Show Ecological and Phylogenetic Divergence from Anuran Tadpoles. Microorganisms, 13(10), 2405. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102405