Abstract

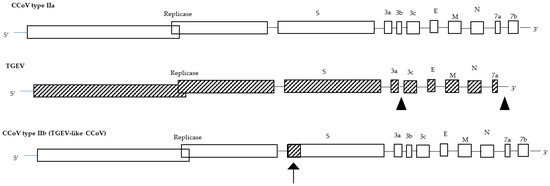

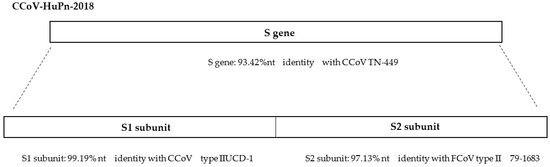

Canine coronavirus (CCoV) is a positive-strand RNA virus generally responsible for mild-to-severe gastroenteritis in dogs. In recent years, new CCoVs with acquired pathogenic characteristics have emerged, turning the spotlight on the evolutionary potential of CCoVs. To date, two genotypes are known, CCoV type I and CCoV type II, sharing up to 96% nucleotide identity in the genome but highly divergent in the spike gene. In 2009, the detection of a novel CCoV type II, which likely originated from a double recombination event with transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), led to the proposal of a new classification: CCoV type IIa, including classical CCoVs and CCoV type IIb, including TGEV-like CCoV. Recently, a virus strictly correlated to CCoV was isolated from children with pneumonia in Malaysia. The HuPn-2018 strain, classified as a novel canine–feline-like recombinant virus, is supposed to have jumped from dogs into people. A novel CoV of canine origin, HuCCoV_Z19Haiti, closely related to the Malaysian strain was also detected in a man with fever after travel to Haiti, suggesting that infection with Malaysian-like strains may occur. These data and the emergence of highly pathogenic CoVs in humans underscore the significant threat that CoV spillovers pose to humans and how we should mitigate this hazard.

1. Introduction

Canine coronavirus (CCoV) is an enveloped virus within the Coronaviridae family with a single-strand positive-sense RNA genome, approximately 27–32kb in size. Based on phylogenetic analyses and genomic structures, CoVs are currently classified within family four genera, Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Gammacoronavirus, which is the largest known RNA genome, and Deltacoronavirus, which recognises bats, birds, and likely rodents as natural reservoirs [1]. CCoV belongs to the genus Alphacoronavirus, which also includes the prototype viruses: feline coronaviruses (FCoVs), transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), mink coronavirus (MinkCoV), ferret coronavirus (FRCoV), and alpaca respiratory coronavirus [2]. Two thirds of the CCoV genome from the 5′ end consists of two large overlapping open reading frames (ORFs), ORF1a and ORF1b, encoding the replicase protein, the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and viral proteases. The remaining genome from the 3′ end contains ORFs encoding the four major structural proteins, spike (S), membrane (M), envelope (E), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins, and for the non-structural proteins ORF3a, ORF3b, ORF3c, ORF7a, and ORF7b [3]. The spike protein, which assembles into trimers on the virion surface to form the distinctive “crown” appearance, is the main inducer of neutralizing antibodies and plays an important role during viral entry, mediating the viral attachment to specific host cell receptors and the fusion between the envelope and the plasma membrane [4]. The S protein ectodomain shares the same organization in all CoVs and is organized in two distinct domains: S1, the N-terminal domain (NTD) responsible for receptor binding, and S2, the C-terminal domain (CTD) responsible for fusion. A notable difference between the S proteins of different CoVs is whether they are cleaved during viral replication. Most Alphacoronaviruses and Betacoronaviruses, with some exceptions, share an uncleaved protein, but the S protein of Gammacoronaviruses and some Betacoronaviruses is cleaved into S1 and S2 domains by a Golgi-resident protease [5]. The most represented and abundant viral structural protein is the M protein, a type III glycoprotein consisting of a short amino-terminal ectodomain, a triple-spanning transmembrane domain, and a long carboxyl-terminal inner domain [6]. It contributes to core stability and can play a role in neutralizing viral infectivity in the presence of complement [7]. The small E protein was recognised as a structural component of the CoVs and is thought to be important for viral envelope assembly [8]. The N protein is a basic phosphoprotein that forms the helical nucleocapsid that binds to the viral RNA and modulates RNA synthesis [4]. The additional ORFs encoding non-structural proteins vary among different CoVs in number, nucleotide sequence, and gene order [9]. Their role is sometimes unknown and most of them are not essential for viral replication but may play a role in virulence [10].

3. Pathobiology of CCoV Infection in Dogs

3.1. Clinical Signs

Clinical disease caused by CCoV in dogs is extremely varied, still not fully understood, and with a clinical evolution influenced by many factors, especially by the genetic characteristics of the strains. The virus is responsible for mild-to-moderate enteritis but young pups may develop severe clinical signs, especially when infections with other pathogens occur simultaneously. In addition, coinfections with intestinal viruses that increase the pathogenicity of CCoV, such as canine adenovirus type 1 (CAdV-1) or canine distemper virus (CDV), have been reported [38,39]. Dual infections with canine parvovirus type 2 (CPV2) are often detected and are especially severe, but CCoV can also enhance the severity of a subsequent CPV2 infection [3]. The main source of infection is represented by faeces, and infection is characterized by oronasal transmission. Clinical signs appear after a short incubation period and are characterized by vomiting, which usually subsides after the first day of illness, and diarrhoea. The elective site of virus replication is the villus tips of the enterocytes of the small intestine, where CCoV is responsible for lytic infection followed by desquamation and shortening of the villi. Virus replication results in malabsorption and the deficiency of digestive enzymes, and consequently in diarrhoea which may already arise 18–72 h post infection and generally persist for 6–9 days when the production of local IgA antibodies restricts both CCoV diffusion within the intestine and the clinical evolution of the disease. However, sometimes, infected dogs may shed the virus intermittently for as long as 6 months after the disappearance of clinical signs [16]. The faeces may be mucous or watery but it is rarely haemorrhagic, except if poor hygienic conditions and coinfection exist; in puppies, the clinical signs can be characterized by dehydration, sensory depression, and anorexia, even in the absence of hyperthermia and leukopenia [3]. Mixed infections with both genotypes (CCoV type I and CCoV type II) are commonly reported, but failure to isolate CCoV type I in cell cultures hampers the acquisition of key information on the pathogenetic role of CCoV infections in dogs and makes it difficult to evaluate the epidemiological and immunological characteristics of CCoV infection [40]. Although serological investigations on the spread of CCoV have widely demonstrated that the virus is present throughout the world, few reports of gastroenteritis in dogs clearly attributable to CCoV are reported and few strains have been cultivated in cell culture [28]. The low detection rate is mostly attributable to the low viral titre excreted in the faeces, especially in long-shedding infected pups, to the low stability of the enveloped virus in the environment, and to the low stability of the RNA [41].

3.2. Emerging CCoV Strains and Associated Diseases

In addition to the classic (mild) enteric CCoVs, several outbreaks of infection characterized by severe clinical signs followed by fatal outcomes are reported. The pantropic CB/05 CCoV type IIa strain isolated in 2005 in Italy caused a systemic disease characterized by high fever, anorexia, lethargy, haemorrhagic diarrhoea, vomiting, leukopenia, and neurological signs with ataxia and seizures. This virulent strain was unexpectedly detected at high titres in the lungs, spleen, liver, kidney, and brain, in addition to the intestinal content [28]. Moreover, the detection of TGEV-like CCoV in 2008 in Italy corroborated the observations on the ability of CCoVs to cause more serious infections than the classic enteric forms. TGEV-like CCoV strains were detected in the faecal samples, in the intestinal contents, and in the internal organs of pups which died with gastrointestinal signs [33]. Despite the fact that infected pups were coinfected with CPV2 that could have played a relevant role in TGEV-like CCoV spreading to the internal organs, this must be a wake-up call on CCoV’s pathogenetic evolutionary ability. The detection of virulent CCoV strains associated with the ability to spread from the enteric tract to other internal organs strongly corroborates the ability of CoVs to modify their virulence and organ tropisms, suggesting the importance of an investigation of the molecular basis of these mechanisms through the assessment of a reverse-genetics system similar to that established for feline infectious peritonitis virus [28,42]. The meaning of all these data is not yet fully understood, but they certainly raise several questions on the pathobiology of CCoVs, both in terms of virus evolution and immunization plans. The genetic differences observed in the spike protein between classical enteric strains and recombinant CCoVs may have particular implications for the efficacy of vaccines. Common vaccines are set up with reference CCoV type IIa strains, and dogs vaccinated with these vaccines might be susceptible to infection or disease caused by TGEV-like CCoVs. Only a vaccination trial with a commercial vaccine and the subsequent challenge with recombinant TGEV-like CCoV could confirm and/or assess the level of cross-reactivity between CCoV type IIa and TGEV-like CCoV type IIb, since a single previous study showed a poor cross-reactivity [33]. Therefore, despite these recombinant viruses being detected in many countries, few data are available in the literature on the clinical features of infection caused by this virus and only some aspects have been clarified. It is nevertheless worthwhile to carefully monitor these viruses to better understand the clinical, pathogenetic, and epidemiological implications of these different genotypes. As a result of the relatively high mutation frequency of RNA viruses, CCoVs are able to rapidly adjust to negative pressures such as those presented by the immune system. Recombination events affecting CCoVs could clarify the evolutionary processes leading to the onset of new strains, as has been observed for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-II and for CCoV type IIa (CB/05) and CCoV type IIb (TGEV-like CCoV). Many aspects of the pathobiology and evolutionary features of CoVs remain to be clarified, among which are the meaning of simultaneous infection by CCoV type I and CCoV type II, the pathogenetic role of these viruses, the immune response, and the efficacy of the currently used vaccines against emerging CCoV strains.

5. Conclusions

Almost 60% of human pathogens and approximately 60% emerging infectious diseases are zoonoses, and zoonoses transmitted from animals to humans represent an increasingly global public health problem since, despite the fact that animal-to-human transmission has always occurred in the past, its frequency has increased in recent years [46,51]. CoVs possess a strong ability to overcome species barriers and to jump from reservoirs to humans, especially from bats which are considered the primary carrier and reservoir for CoVs and other several viruses. Considering the large diffusion and genetic diversity of bat CoVs, the large number of bats living in communities, and their ability to travel long distances, it cannot be excluded that new viruses may emerge in the future. This is a worrying hypothesis which, despite its impact, has not seen the implementation of any contrasting action to limit human–animal cohabitation (especially with wildlife animals). In alignment with the concept of “One Health”, the detection of Malaysian and Haitian CoVs in humans not only confirms the genetic plasticity of CoVs but should cause alarm and induce the scientific community to carry out continuous genomic surveillance both in wildlife and in companion animals to avoid the next possible spillovers (species jumps) from animals to humans and future severe heath emergencies [12,16,52]. In conclusion, the recent reports of human infections caused by canine coronavirus-like strains could be a meaningful warning: CCoVs, generally considered not particularly aggressive for dogs, could assume a relevant and non-negligible pathobiological role leading to the image of “a wolf in sheep’s clothing”.

Author Contributions

.Conceptualization, A.B. and A.P.; validation, N.D.; formal analysis, F.P.; investigation, M.G.; resources, N.D.; data curation, F.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; writing—review and editing, A.P.; visualization, N.D.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, N.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

CCoVs research was supported by EU funding within the MUR PNRR Extended Partnership Initiative on Emerging Infectious Diseases (Project no. PE00000007, INF-ACT).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Decaro, N.; Martella, V.; Saif, L.J.; Buonavoglia, C. COVID-19 from Veterinary Medicine and One Health Perspectives: What Animal Coronaviruses Have Taught Us. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 131, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.J.; Lefkowitz, E.J.; King, A.M.Q.; Bamford, D.H.; Breitbart, M.; Davison, A.J.; Ghabrial, S.A.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Knowles, N.J.; Krell, P.; et al. Ratification Vote on Taxonomic Proposals to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 1837–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratelli, A. The Evolutionary Processes of Canine Coronaviruses. Adv. Virol. 2011, 2011, 562831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enjuanes, L.; Brian, D.; Cavanagh, D.; Holmes, K.; Lai, M.M.C.; Laude, H.; Masters, P.; Rottier, P.; Siddell, S.; Spaan, W.J.M.; et al. Virus Taxonomy; Murphy, F.A., Fauquet, C.M., Bishop, D.H.L., Ghabrial, S.A., Jarvis, A.W., Martelli, G.P., Mayo, M.A., Summers, M.D., et al., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1995; ISBN 978-3-211-82594-5. [Google Scholar]

- Belouzard, S.; Millet, J.K.; Licitra, B.N.; Whittaker, G.R. Mechanisms of Coronavirus Cell Entry Mediated by the Viral Spike Protein. Viruses 2012, 4, 1011–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rottier, P.J.M. The Coronavirus Membrane Glycoprotein. In The Coronaviridae; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 115–139. [Google Scholar]

- Escors, D.; Ortego, J.; Laude, H.; Enjuanes, L. The Membrane M Protein Carboxy Terminus Binds to Transmissible Gastroenteritis Coronavirus Core and Contributes to Core Stability. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 1312–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vennema, H.; Godeke, G.J.; Rossen, J.W.; Voorhout, W.F.; Horzinek, M.C.; Opstelten, D.J.; Rottier, P.J. Nucleocapsid-Independent Assembly of Coronavirus-like Particles by Co-Expression of Viral Envelope Protein Genes. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-J.; Shieh, C.-K.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Koonin, E.v.; la Monica, N.; Tuler, J.; Bagdzhadzhyan, A.; Lai, M.M.C. The Complete Sequence (22 Kilobases) of Murine Coronavirus Gene 1 Encoding the Putative Proteases and RNA Polymerase. Virology 1991, 180, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decaro, N.; Buonavoglia, C. An Update on Canine Coronaviruses: Viral Evolution and Pathobiology. Vet. Microbiol. 2008, 132, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, B.; Zhang, X.; Bai, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, C.; Lin, W. Epidemiological Investigation of Canine Coronavirus Infection in Chinese Domestic Dogs: A Systematic Review and Data Synthesis. Prev. Vet. Med. 2022, 209, 105792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratelli, A.; Buonavoglia, A.; Lanave, G.; Tempesta, M.; Camero, M.; Martella, V.; Decaro, N. One World, One Health, One Virology of the Mysterious Labyrinth of Coronaviruses: The Canine Coronavirus Affair. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, e646–e647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binn, L.N.; Lazar, E.C.; Keenan, K.P.; Huxsoll, D.L.; Marchwicki, R.H.; Strano, A.J. Recovery and Characterization of a Coronavirus from Military Dogs with Diarrhea. In Proceedings: Annual Meeting; United States Animal Health Association: St. Joseph, MO, USA, 1974; pp. 359–366. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.-J.; Zhang, W.; Liang, J.; Lu, M.; Wang, R.; Li, G.; He, J.-W.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Xing, G.; et al. Etiology and Genetic Evolution of Canine Coronavirus Circulating in Five Provinces of China, during 2018–2019. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 145, 104209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, C.; Guo, D.; Wang, X.; Wei, S.; Geng, Y.; Wang, E.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Su, M.; et al. Co-Circulation of Canine Coronavirus I and IIa/b with High Prevalence and Genetic Diversity in Heilongjiang Province, Northeast China. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratelli, A.; Tempesta, M.; Elia, G.; Martella, V.; Decaro, N.; Buonavoglia, C. The Knotty Biology of Canine Coronavirus: A Worrying Model of Coronaviruses’ Danger. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 144, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratelli, A.; Martella, V.; Elia, G.; Decaro, N.; Aliberti, A.; Buonavoglia, D.; Tempesta, M.; Buonavoglia, C. Variation of the Sequence in the Gene Encoding for Transmembrane Protein M of Canine Coronavirus (CCV). Mol. Cell. Probes 2001, 15, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratelli, A.; Martella, V.; Pistello, M.; Elia, G.; Decaro, N.; Buonavoglia, D.; Camero, M.; Tempesta, M.; Buonavoglia, C. Identification of Coronaviruses in Dogs That Segregate Separately from the Canine Coronavirus Genotype. J. Virol. Methods 2003, 107, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratelli, A.; Martella, V.; Decaro, N.; Tinelli, A.; Camero, M.; Cirone, F.; Elia, G.; Cavalli, A.; Corrente, M.; Greco, G.; et al. Genetic Diversity of a Canine Coronavirus Detected in Pups with Diarrhoea in Italy. J. Virol. Methods 2003, 110, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, A.; Decaro, N.; Schellen, P.; Rottier, P.J.M.; Buonavoglia, C.; Haijema, B.-J.; de Groot, R.J. Gain, Preservation, and Loss of a Group 1a Coronavirus Accessory Glycoprotein. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 10312–10317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilbag, K.; Yilmaz, Z.; Torun, S.; Pratelli, A. Canine Coronavirus Infection in Turkish Dog Population. J. Vet. Med. Ser. B 2004, 51, 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Martella, V.; Ricci, D.; Elia, G.; Desario, C.; Campolo, M.; Cavaliere, N.; di Trani, L.; Tempesta, M.; Buonavoglia, C. Genotype-Specific Fluorogenic RT-PCR Assays for the Detection and Quantitation of Canine Coronavirus Type I and Type II RNA in Faecal Samples of Dogs. J. Virol. Methods 2005, 130, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley, R.D. The S Gene of Canine Coronavirus, Strain UCD-1, Is More Closely Related to the S Gene of Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus than to That of Feline Infectious Peritonitis Virus. Virus Res. 1999, 61, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, M.J.; Harrison, G.A.; Monckton, R.P.; McOrist, S.; Lehrbach, P.R.; Deane, E.M. Identification of Canine Coronavirus Strains from Feces by S Gene Nested PCR and Molecular Characterization of a New Australian Isolate. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 1036–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Morgado, J.M.; Poynter, S.; Morris, T.H. Molecular Characterization of a Virulent Canine Coronavirus BGF Strain. Virus Res. 2004, 104, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escutenaire, S.; Isaksson, M.; Renström, L.H.M.; Klingeborn, B.; Buonavoglia, C.; Berg, M.; Belák, S.; Thorén, P. Characterization of Divergent and Atypical Canine Coronaviruses from Sweden. Arch. Virol. 2007, 152, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decaro, N.; Cordonnier, N.; Demeter, Z.; Egberink, H.; Elia, G.; Grellet, A.; le Poder, S.; Mari, V.; Martella, V.; Ntafis, V.; et al. European Surveillance for Pantropic Canine Coronavirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonavoglia, C.; Decaro, N.; Martella, V.; Elia, G.; Campolo, M.; Desario, C.; Castagnaro, M.; Tempesta, M. Canine Coronavirus Highly Pathogenic for Dogs. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 492–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.D.; Barros, I.N.; Budaszewski, R.F.; Weber, M.N.; Mata, H.; Antunes, J.R.; Boabaid, F.M.; Wouters, A.T.B.; Driemeier, D.; Brandão, P.E.; et al. Characterization of Pantropic Canine Coronavirus from Brazil. Vet. J. 2014, 202, 659–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, F.; Fusco, G.; Mari, V.; Occhiogrosso, L.; Miletti, G.; Brunetti, R.; Galiero, G.; Desario, C.C.; Cirilli, M.; Decaro, N. Circulation of Pantropic Canine Coronavirus in Autochthonous and Imported Dogs, Italy. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 1991–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Martella, V.; Elia, G.; Campolo, M.; Desario, C.; Cirone, F.; Tempesta, M.; Buonavoglia, C. Molecular Characterisation of the Virulent Canine Coronavirus CB/05 Strain. Virus Res. 2007, 125, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrewegh, A.A.P.M.; Smeenk, I.; Horzinek, M.C.; Rottier, P.J.M.; de Groot, R.J. Feline Coronavirus Type II Strains 79-1683 and 79-1146 Originate from a Double Recombination between Feline Coronavirus Type I and Canine Coronavirus. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 4508–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Mari, V.; Campolo, M.; Lorusso, A.; Camero, M.; Elia, G.; Martella, V.; Cordioli, P.; Enjuanes, L.; Buonavoglia, C. Recombinant Canine Coronaviruses Related to Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus of Swine Are Circulating in Dogs. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 1532–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Mari, V.; Elia, G.; Addie, D.D.; Camero, M.; Lucente, M.S.; Martella, V.; Buonavoglia, C. Recombinant Canine Coronaviruses in Dogs, Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010, 16, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regan, A.D.; Millet, J.K.; Tse, L.P.v.; Chillag, Z.; Rinaldi, V.D.; Licitra, B.N.; Dubovi, E.J.; Town, C.D.; Whittaker, G.R. Characterization of a Recombinant Canine Coronavirus with a Distinct Receptor-Binding (S1) Domain. Virology 2012, 430, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corapi, W.v.; Olsen, C.W.; Scott, F.W. Monoclonal Antibody Analysis of Neutralization and Antibody-Dependent Enhancement of Feline Infectious Peritonitis Virus. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 6695–6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Song, X.; Zhang, B. Detection and Molecular Characteristics of Canine Coronavirus in Chengdu City, Southwest China from 2020 to 2021. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 166, 105548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decaro, N.; Camero, M.; Greco, G.; Zizzo, N.; Elia, G.; Campolo, M.; Pratelli, A.; Buonavoglia, C. Canine Distemper and Related Diseases: Report of a Severe Outbreak in a Kennel. New Microbiol. 2004, 27, 177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Pratelli, A.; Martella, V.; Elia, G.; Tempesta, M.; Guarda, F.; Capucchio, M.T.; Carmichael, L.E.; Buonavoglia, C. Severe Enteric Disease in an Animal Shelter Associated with Dual Infections by Canine Adenovirus Type 1 and Canine Coronavirus. J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health 2001, 48, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratelli, A.; Decaro, N.; Tinelli, A.; Martella, V.; Elia, G.; Tempesta, M.; Cirone, F.; Buonavoglia, C. Two Genotypes of Canine Coronavirus Simultaneously Detected in the Fecal Samples of Dogs with Diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 1797–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavisky, J.; Pinchbeck, G.L.; German, A.J.; Dawson, S.; Gaskell, R.M.; Ryvar, R.; Radford, A.D. Prevalence of Canine Enteric Coronavirus in a Cross-Sectional Survey of Dogs Presenting at Veterinary Practices. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 140, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haijema, B.J.; Volders, H.; Rottier, P.J.M. Switching Species Tropism: An Effective Way to Manipulate the Feline Coronavirus Genome. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 4528–4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolja, V.V.; Carrington, J.C. Evolution of Positive-Strand RNA Viruses. Semin. Virol. 1992, 3, 315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Vlasova, A.N.; Kenney, S.P.; Saif, L.J. Emerging and Re-emerging Coronaviruses in Pigs. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2019, 34, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. A Pneumonia Outbreak Associated with a New Coronavirus of Probable Bat Origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, B.J.; Morand, S.; Gray, J.S. Ecosystem Change and Zoonoses in the Anthropocene. Zoonoses Public Health 2018, 65, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlasova, A.N.; Diaz, A.; Damtie, D.; Xiu, L.; Toh, T.-H.; Lee, J.S.-Y.; Saif, L.J.; Gray, G.C. Novel Canine Coronavirus Isolated from a Hospitalized Patient with Pneumonia in East Malaysia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lednicky, J.A.; Tagliamonte, M.S.; White, S.K.; Blohm, G.M.; Alam, M.M.; Iovine, N.M.; Salemi, M.; Mavian, C.; Morris, J.G. Isolation of a Novel Recombinant Canine Coronavirus from a Visitor to Haiti: Further Evidence of Transmission of Coronaviruses of Zoonotic Origin to Humans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, e1184–e1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domańska-Blicharz, K.; Woźniakowski, G.; Konopka, B.; Niemczuk, K.; Welz, M.; Rola, J.; Socha, W.; Orłowska, A.; Antas, M.; Śmietanka, K.; et al. Animal Coronaviruses in the Light of COVID-19. J. Vet. Res. 2020, 64, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lednicky, J.A.; Tagliamonte, M.S.; White, S.K.; Elbadry, M.A.; Alam, M.M.; Stephenson, C.J.; Bonny, T.S.; Loeb, J.C.; Telisma, T.; Chavannes, S.; et al. Independent Infections of Porcine Deltacoronavirus among Haitian Children. Nature 2021, 600, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolhouse, M.E.J.; Gowtage-Sequeria, S. Host Range and Emerging and Reemerging Pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 1842–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, F.; Omar, A.H.; Buonavoglia, C.; Pratelli, A. SARS-CoV-2 and Animals: From a Mirror Image to a Storm Warning. Pathogens 2023, 11, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).