Olive Fungal Epiphytic Communities Are Affected by Their Maturation Stage

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Olive Fruit Sampling

2.2. Preparation of DNA from Fungal Epiphytes

2.3. Fungal ITS2 Amplification and Sequencing

2.4. Processing of Sequencing Data

2.5. Diversity of Fungal Epiphytes

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Epiphytic Fungal Community Diversity in Olives from Different Conditions

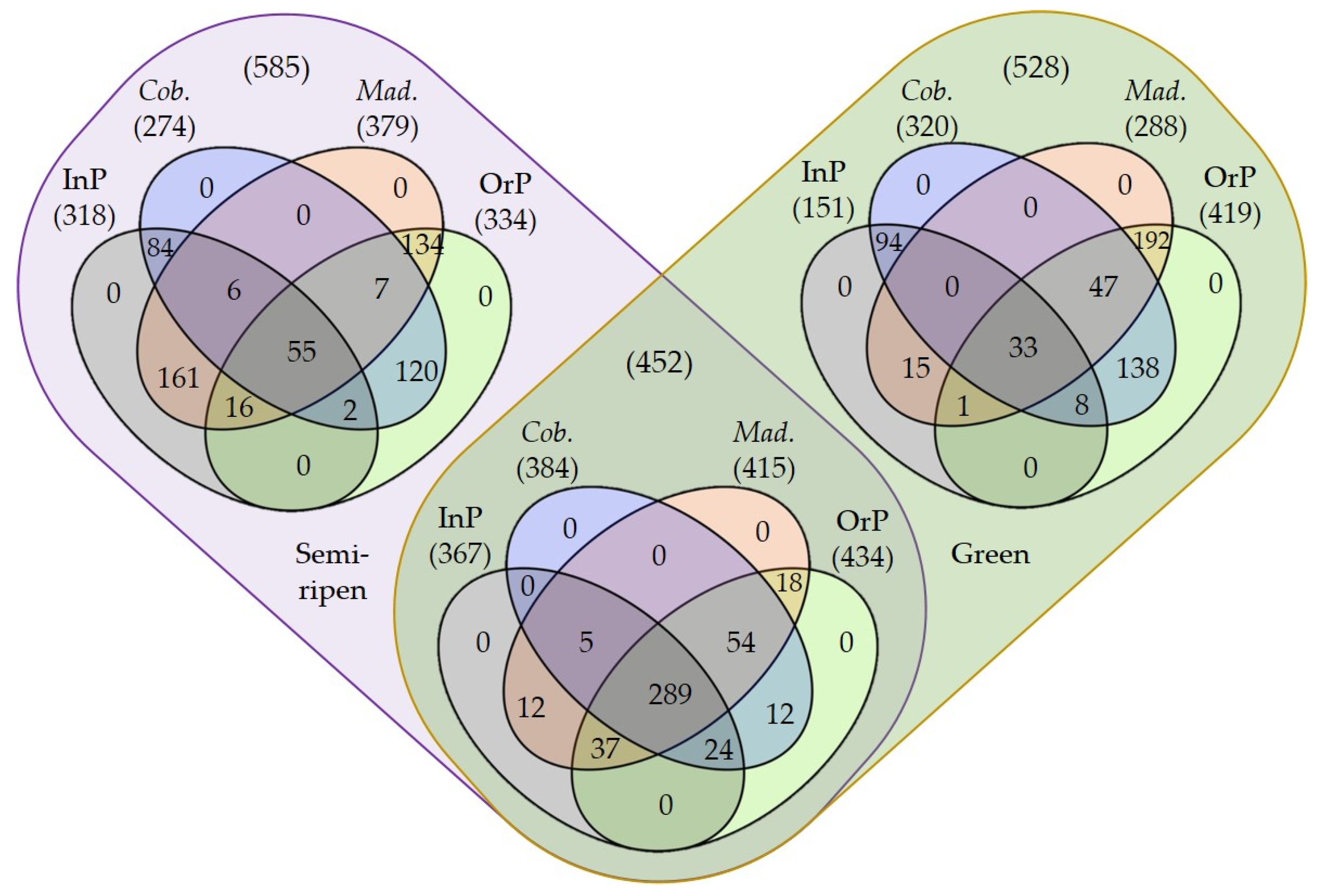

3.2. Epiphytic Fungal Community Structure in Olives from Different Conditions

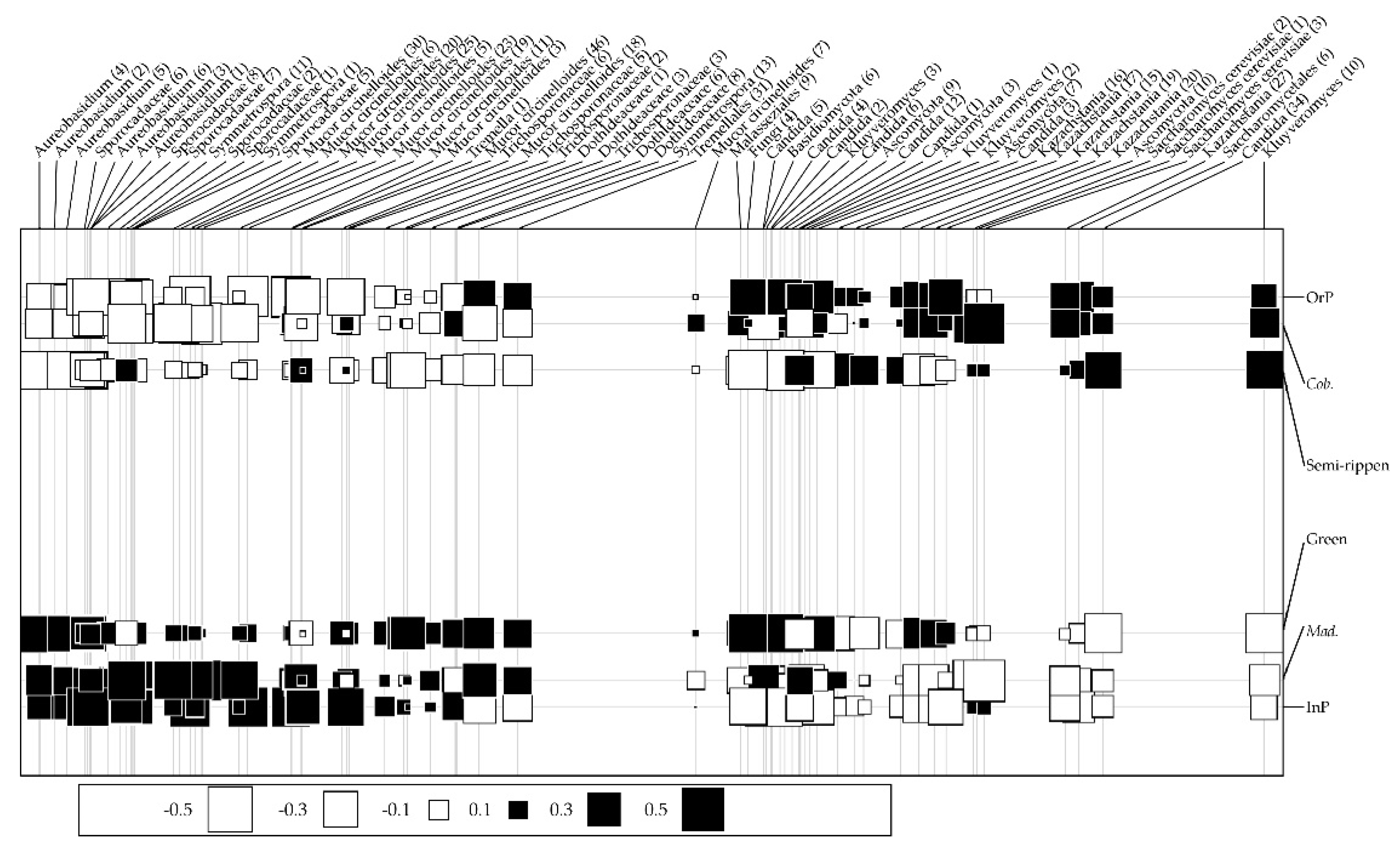

3.3. Discriminant Fungal Epiphytes in Olives from Different Conditions

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Torres, M.; Pierantozzi, P.; Searles, P.; Rousseaux, M.C.; García-Inza, G.; Miserere, A.; Bodoira, R.; Contreras, C.; Maestri, D. Olive cultivation in the southern hemisphere: Flowering, water requirements and oil quality responses to new crop environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Todde, G.; Murgia, L.; Deligios, P.A.; Hogan, R.; Carrelo, I.; Moreira, M.; Pazzona, A.; Ledda, L.; Narvarte, L. Energy and environmental performances of hybrid photovoltaic irrigation systems in Mediterranean intensive and super-intensive olive orchards. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2514–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montanaro, G.; Xiloyannis, C.; Nuzzo, V.; Dichio, B. Orchard management, soil organic carbon and ecosystem services in Mediterranean fruit tree crops. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 217, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Rang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Chen, W.; Tian, F.; Yin, H.; Dai, L. The succession pattern of soil microbial communities and its relationship with tobacco bacterial wilt. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berg, G.; Köberl, M.; Rybakova, D.; Müller, H.; Grosch, R.; Smalla, K. Plant microbial diversity is suggested as the key to future biocontrol and health trends. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusstatscher, P.; Cernava, T.; Harms, K.; Maier, J.; Eigner, H.; Berg, G.; Zachow, C. Disease incidence in sugar beet fields is correlated with microbial diversity and distinct biological markers. Phytobiomes J. 2019, 3, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gouvinhas, I.; Martins-Lopes, P.; Carvalho, T.; Barros, A.; Gomes, S. Impact of Colletotrichum acutatum pathogen on olive phenylpropanoid metabolism. Agriculture 2019, 9, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vorholt, J.A. Microbial life in the phyllosphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 828–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azabou, M.C.; Gharbi, Y.; Medhioub, I.; Ennouri, K.; Barham, H.; Tounsi, S.; Triki, M.A. The endophytic strain Bacillus velezensis OEE1: An efficient biocontrol agent against Verticillium wilt of olive and a potential plant growth promoting bacteria. Biol. Control 2020, 142, 104168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannaa, M.; Seo, Y.S. Plants under the attack of allies: Moving towards the plant pathobiome paradigm. Plants 2021, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacava, P.T.; Azevedo, J.L. Biological Control of Insect-Pest and Diseases by Endophytes. In Advances in Endophytic Research; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2014; pp. 231–256. [Google Scholar]

- Sergeeva, V.; Nair, N.G.; Spooner-Hart, R. Evidence of early flower infection in olives (Olea europaea) by Colletotrichum acutatum and C. gloeosporioides causing anthracnose disease. Australas. Plant Dis. Notes 2008, 3, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliveira, R.; Moral, J.; Bouhmidi, K.; Trapero, A. Caracterización morfológica y cultural de aislados de Colletotrichum spp. causantes de la Antracnosis del olivo. Boletín Sanid. Veg. Plagas 2005, 31, 531–548. [Google Scholar]

- Cacciola, S.O.; Sinatra, R.F.; Agosteo, G.E.; Schena, L.; Frisullo, S.; di San Lio, G.M. Olive anthracnose. J. Plant Pathol. 2012, 94, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Malavolta, C.; Perdikis, D. Crop Specific Technical Guidelines for Integrated Production of Olives. IOBC-WPRS Commission IP Guidelines. 2018. Available online: https://www.iobc-wprs.org/ip_practical_guidelines/index.html (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Beltrán, G.; Uceda, M.; Hermoso, M.; Frías, L. Maduración. In El Cultivo del Olivo, 6th ed.; Barranco, D., Fernández-Escobar, R., Rallo, L., Eds.; Ediciones Mundi-Prensa y Junta de Andalucía: Madrid, Spain, 2008; pp. 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, E.; Kowsari, M.; Azadfar, D.; Salehi Jouzani, G. Rapid and economical protocols for genomic and metagenomic DNA extraction from oak (Quercus brantii Lindl.). Ann. For. Sci. 2018, 75, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, J.I.; Zuccaro, A. Sequences, the environment and fungi. Mycologist 2006, 20, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Põlme, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Yorou, N.S.; Wijesundera, R.; Ruiz, L.V.; Vasco-Palacios, A.M.; Thu, P.Q.; Suija, A.; et al. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 2014, 346, 1256688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andrews, S. FastQC—A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data [Internet]. 2010. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Joshi, N.A.; Fass, J.N. Sickle: A Sliding-Window, Adaptive, Quality-Based Trimming Tool for FastQ Files [Internet]. 2011. Available online: https://github.com/najoshi/sickle (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Nurk, S.; Bankevich, A.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.; Korobeynikov, A.; Lapidus, A.; Prjibelsky, A.; Pyshkin, A.; Sirotkin, A.; Sirotkin, Y.; et al. Assembling genomes and mini-metagenomes from highly chimeric reads. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 158–170. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, R.C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2460–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aronesty, E. ea-utils: Command-Line Tools for Processing Biological Sequencing Data. 2011. Available online: https://expressionanalysis.github.io/ea-utils/ (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Albanese, D.; Fontana, P.; De Filippo, C.; Cavalieri, D.; Donati, C. MICCA: A complete and accurate software for taxonomic profiling of metagenomic data. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nilsson, R.H.; Larsson, K.H.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Jeppesen, T.S.; Schigel, D.; Kennedy, P.; Picard, K.; Glöckner, F.O.; Tedersoo, L.; et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: Handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D259–D264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Peña, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hughes, J.B.; Bohannan, B.J.M. Application of ecological diversity statistics in microbial ecology. In Molecular Microbial Ecology Manual, 2nd ed.; Kowalchuk, G.A., de Bruijn, F.J., Head, I.M., Akkermans, A.D., van Elsas, J.D., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, T.C.J.; Walsh, K.A.; Harris, J.A.; Moffett, B.F. Using ecological diversity measures with bacterial communities. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2003, 43, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. Past: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 178. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, P.A.; Seaby, R.M.H. Community Analysis Package; Pisces Conservation Ltd.: Lymington, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, D.R.; Edwards, T.C.; Beard, K.H.; Cutler, A.; Hess, K.T.; Gibson, J.; Lawler, J.J. Random forests for classification in ecology. Ecology 2007, 88, 2783–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dolédec, S.; Chessel, D. Co-inertia analysis: An alternative method for studying species–environment relationships. Freshw. Biol. 1994, 31, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dray, S.; Dufour, A.B. The ade4 package: Implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdelfattah, A.; Li Destri Nicosia, M.G.; Cacciola, S.O.; Droby, S.; Schena, L. Metabarcoding analysis of fungal diversity in the phyllosphere and carposphere of olive (Olea europaea). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fernández-González, A.J.; Villadas, P.J.; Gómez-Lama Cabanás, C.; Valverde-Corredor, A.; Belaj, A.; Mercado-Blanco, J.; Fernández-López, M. Defining the root endosphere and rhizosphere microbiomes from the World Olive Germplasm Collection. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costa, D.; Fernandes, T.; Martins, F.; Pereira, J.A.; Tavares, R.M.; Santos, P.M.; Baptista, P.; Lino-Neto, T. Illuminating Olea europaea L. endophyte fungal community. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 245, 126693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granado, J.; Thürig, B.; Kieffer, E.; Petrini, L.; Fließbach, A.; Tamm, L.; Weibel, F.P.; Wyss, G.S. Culturable fungi of stored “golden delicious” apple fruits: A one-season comparison study of organic and integrated production systems in Switzerland. Microb. Ecol. 2008, 56, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, G.; Vallance, J.; Mercier, A.; Albertin, W.; Stamatopoulos, P.; Rey, P.; Lonvaud, A.; Masneuf-Pomarède, I. Influence of the farming system on the epiphytic yeasts and yeast-like fungi colonizing grape berries during the ripening process. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 177, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, T.; Pereira, J.A.; Benhadi, J.; Lino-Neto, T.; Baptista, P. Endophytic and epiphytic phyllosphere fungal communities are shaped by different environmental factors in a mediterranean ecosystem. Microb. Ecol. 2018, 76, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Preto, G.; Martins, F.; Pereira, J.A.; Baptista, P. Fungal community in olive fruits of cultivars with different susceptibilities to anthracnose and selection of isolates to be used as biocontrol agents. Biol. Control 2017, 110, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taîbi, A.; Rivallan, R.; Broussolle, V.; Pallet, D.; Lortal, S.; Meile, J.C.; Constancias, F. Terroir is the main driver of the epiphytic bacterial and fungal communities of mango carposphere in Reunion Island. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, J.K.; Yuan, L.; Layeghifard, M.; Wang, P.W.; Guttman, D.S. Seasonal community succession of the phyllosphere microbiome. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2015, 28, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martins, F.; Cameirão, C.; Mina, D.; Benhadi-Marín, J.; Pereira, J.A.; Baptista, P. Endophytic fungal community succession in reproductive organs of two olive tree cultivars with contrasting anthracnose susceptibilities. Fungal Ecol. 2021, 49, 101003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Li, N.; Cao, M.; Huang, Q.; Chen, G.; Xie, S.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, G.; Li, W. Diversity of epiphytic fungi on the surface of Kyoho grape berries during ripening process in summer and winter at Nanning region, Guangxi, China. Fungal Biol. 2019, 123, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bill, M.; Chidamba, L.; Gokul, J.K.; Korsten, L. Mango endophyte and epiphyte microbiome composition during fruit development and post-harvest stages. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freimoser, F.M.; Rueda-Mejia, M.P.; Tilocca, B.; Migheli, Q. Biocontrol yeasts: Mechanisms and applications. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, F.; Bonthond, G.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Cai, L.; Crous, P.W. Sporocadaceae, a family of coelomycetous fungi with appendage-bearing conidia. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 92, 287–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, V.; Romboli, Y.; Barbato, D.; Mari, E.; Venturi, M.; Guerrini, S.; Granchi, L. Indigenous Aureobasidium pullulans strains as biocontrol agents of Botrytis cinerea on grape berries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, F.; Antelmi, I.; Labarile, R.; Sion, V.; Pentimone, I. Biological control of olive anthracnose. In Acta Horticulturae; International Society for Horticultural Science: Leuven, Belgium, 2018; pp. 439–444. [Google Scholar]

- López-Moral, A.; Agustí-Brisach, C.; Trapero, A. Plant biostimulants: New insights into the biological control of Verticillium wilt of olive. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Diversity Indexes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | 1-D | H’ | |||

| Green | Organic production | cv. Madural | 195 ± 79 * | 0.970 ± 0.008 | 4.261 ± 0.387 |

| cv. Cobrançosa | 147 ± 61 | 0.957 ± 0.019 | 3.909 ± 0.424 | ||

| Integrated production | cv. Madural | 75 ± 39 * | 0.917 ± 0.044 | 3.055 ± 0.630 | |

| cv. Cobrançosa | 77 ± 28 | 0.942 ± 0.042 | 3.480 ± 0.587 | ||

| Semi-ripen | Organic production | cv. Madural | 110 ± 61 | 0.945 ± 0.032 | 3.587 ± 0.697 |

| cv. Cobrançosa | 131 ± 53 | 0.957 ± 0.021 | 3.831 ± 0.524 | ||

| Integrated production | cv. Madural | 164 ± 45 | 0.966 ± 0.023 | 4.166 ± 0.470 | |

| cv. Cobrançosa | 97 ± 63 | 0.941 ± 0.026 | 3.430 ± 0.595 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castro, J.; Costa, D.; Tavares, R.M.; Baptista, P.; Lino-Neto, T. Olive Fungal Epiphytic Communities Are Affected by Their Maturation Stage. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10020376

Castro J, Costa D, Tavares RM, Baptista P, Lino-Neto T. Olive Fungal Epiphytic Communities Are Affected by Their Maturation Stage. Microorganisms. 2022; 10(2):376. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10020376

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro, Joana, Daniela Costa, Rui M. Tavares, Paula Baptista, and Teresa Lino-Neto. 2022. "Olive Fungal Epiphytic Communities Are Affected by Their Maturation Stage" Microorganisms 10, no. 2: 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10020376

APA StyleCastro, J., Costa, D., Tavares, R. M., Baptista, P., & Lino-Neto, T. (2022). Olive Fungal Epiphytic Communities Are Affected by Their Maturation Stage. Microorganisms, 10(2), 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10020376