A Two-Phase Switching Adaptive Sliding Mode Control Achieving Smooth Start-Up and Precise Tracking for TBM Hydraulic Cylinders

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

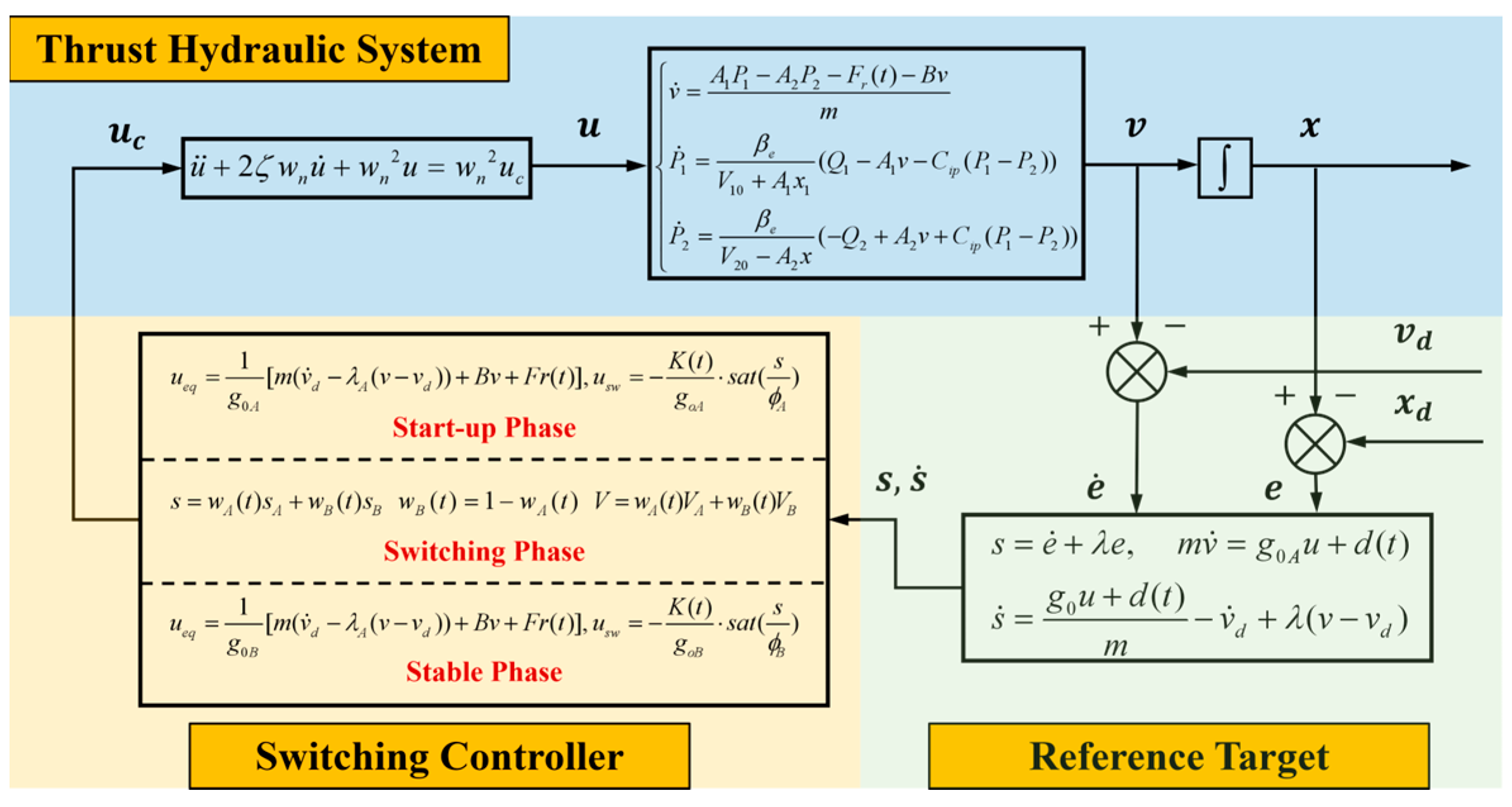

- We formulate a precise state-space model of the thrust hydraulic system, and experimentally obtain the cylinder’s external load conditions and system parameters.

- (2)

- We propose an ASMC-based switching controller that under load fluctuations simultaneously achieves high tracking accuracy and enhanced start-up velocity stability.

2. Introduction to the Hydraulic System and Modeling

2.1. Hydraulic System and Components

2.2. Establishment of State Space Model

2.3. Determination of the Periodic Load Curve

2.4. Determination of Unknown Parameters

3. Design of the ASMC Controller

3.1. Design of the Controller A

3.2. Design of the Controller B

3.3. Stability Analysis

3.4. Control Performance Analysis

4. Design and Analysis of the Switching Controller

4.1. Design of the Switching Controller

4.2. Analysis of the Switching Controller

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, B.; Li, Q.; Xu, Z.; Niu, S.; Nie, X. A Safety Risk Assessment Method for TBM Tunnel Construction Based on Attribute Interval Identification Theory. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Xu, B.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, Z. Performance Optimization of Hard Rock Tunnel Boring Machine Using Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleş, S. Cutting Performance Assessment of a Medium Weight Roadheader at Çayırhan Coal Mine. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Türkiye, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Xie, M.; Wang, H. Prediction Method of Cutting Stability of Roadheader Based on the Newton-Lagrange Mixed Discrete Method. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y. Vibration Characteristics Analysis of Roadheader Rotary Cutting Process. Results Eng. 2023, 19, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Yao, J.; Hu, J.; Feng, G. Output Feedback Active Disturbance Rejection Control of an Electro-Hydraulic Servo System Based on Command Filter. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 38, 103169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Dong, X.; Li, J. Cross-Coupled Sliding Mode Synchronous Control for a Double Lifting Point Hydraulic Hoist. Sens. 2023, 23, 9387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qiu, C.; Huang, J.; Tan, Q.; Sun, S.; Gong, Z. Terminal Sliding Mode Force Control Based on Modified Fast Double-Power Reaching Law for Aerospace Electro-Hydraulic Load Simulator of Large Loads. Actuators 2024, 13, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, K.; Qian, W.; Shen, W.; Yuan, X. Adaptive Backstepping Sliding Mode Control of Electro-Hydraulic Servo System Based on Extended State Observer. Mach. Tool Hydraul. 2023, 51, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.D.; Do, T.C.; Truong, H.V.A. Output Feedback-Based Neural Network Sliding Mode Control for Electro-Hydrostatic Systems with Unknown Uncertainties. Machines 2024, 12, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.; Zhang, R.; Liu, M.; Yu, J. Nonlinear disturbance observer-based sliding mode controller for underwater vehicles. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Signal Processing Systems (ICSPS), Zhenjiang, China, 18–20 November 2022; pp. 547–550. [Google Scholar]

- Ruderman, M.; Fridman, L.; Pasolli, P. Virtual sensing of load forces in hydraulic actuators using second- and higher-order sliding modes. Control Eng. Pract. 2019, 92, 104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Song, X. Improved Nonlinear Extended State Observer-Based Sliding-Mode Rotary Control for the Rotation System of a Hydraulic Roofbolter. Entropy 2022, 24, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Jin, B.; Dong, J.; Yao, Q.; Jin, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, B. Sliding Mode Repetitive Control Based on the Unknown Dynamics Estimator of a Two-Stage Supply Pressure Hydraulic Hexapod Robot. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.X.; Li, Z.; Xiao, J. Compensation Function Observer-Based Backstepping Sliding-Mode Control of Uncertain Electro-Hydraulic Servo System. Machines 2024, 12, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.-W.; Ni, T.; Zhang, Z.-X. Parameter Adaptive Sliding Mode Trajectory Tracking Strategy with Initial Value Identification for the Swing in a Hydraulic Construction Robot. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.S.; Kim, W. Robust Nonlinear Position Control with Extended State Observer for Single-Rod Electro-Hydrostatic Actuator. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Lao, Z.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y.; Sun, X.; Tang, J.; Chen, Z. Disturbance Observer-Based Sliding Mode Controller for Underwater Electro-Hydrostatic Actuator Affected by Seawater Pressure. Machines 2022, 10, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zheng, X. Sliding Mode Control of Electro-Hydraulic Servo System Based on Double Observers. Mech. Sci. 2024, 15, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmat, M.F.; Zulfatman; Husain, A.R.; Ishaque, K.; Sam, Y.M.; Ghazali, R.; Rozali, S.M. Modeling and Controller Design of an Industrial Hydraulic Actuator System in the Presence of Friction and Internal Leakage. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2011, 6, 3502–3517. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, J.; Gan, M.; Zong, H.; Wang, X.; Huang, H.; Su, Q.; Xu, B. Modeling and Parameter Sensitivity Analysis of Valve-Controlled Helical Hydraulic Rotary Actuator System. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2022, 35, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stosiak, M.; Karpenko, M.; Skačkauskas, P.; Deptuła, A. Identification of Pressure Pulsation Spectrum in a Hydraulic System with a Vibrating Proportional Valve. J. Vib. Control 2024, 30, 4917–4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Vedova, M.D.L.; Berri, P.C. A New Simplified Fluid Dynamic Model for Digital Twins of Electrohydraulic Servovalves. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. Int. J. 2021, 94, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gong, G.; Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Chen, G. Towards Autonomous and Optimal Excavation of Shield Machine: A Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Approach. J. Zhejiang Univ.-SCI. A 2022, 23, 458–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nápoles-Báez, Y.; González-Yero, G.; Martínez, R.; Valeriano, Y.; Nuñez-Alvarez, J.R.; Llosas-Albuerne, Y. Modeling and Control of the Hydraulic Actuator in a Ladle Furnace. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Su, X. An Adaptive Sliding Mode Controller for Electro-hydraulic Servo Systems Combining Offline Training and Online Estimation. Asian J. Control 2024, 26, 1204–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Penetration Depth | Mean | Max | Min | Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 mm | 29,037.16 | 40,994.91 | 18,162.57 | 4.96 |

| 6 mm | 29,314.81 | 40,904.33 | 20,248.69 | 4.94 |

| Parameters | Values | Units | Physical Meanings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | kg | equivalent load mass | |

| 0.015 | m2 | rodless side area | |

| 0.008 | m2 | rod side area | |

| 0.010 | m3 | rodless side initial volume | |

| 0.025 | m3 | rod side initial volume | |

| 20 | MPa | supply pressure | |

| 870 | kg/m3 | oil density | |

| 0.65 | - | discharge coefficient | |

| 200 | rad/s | natural frequency | |

| 0.8 | - | damping ratio | |

| 0.50 | mm | upper limit of valve |

| Unknown Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Range of Values | 0.8 × 109~1.6 × 109 | 1.0 × 10−13~5.0 × 10−12 | 2000~8000 |

| Units | Pa | m3/(s·Pa) | (N·s)/m |

| Identified Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Values | 1.4 × 109 | 7.2 × 10−13 | 3200 |

| Units | Pa | m3/(s·Pa) | (N·s)/m |

| Controllers | Parameters | Values | Parameter Meanings |

|---|---|---|---|

| PID Controller | 800 | proportional gain | |

| 0.1 | integral gain | ||

| 0.0005 | derivative gain | ||

| Controller A | 10 | adaptation gain | |

| 30 | base gain | ||

| 0.01 | boundary-layer thickness | ||

| 1.0 × 108 | linear gain | ||

| Controller B | 4.0 × 103 | adaptation gain | |

| 1.75 × 103 | base gain | ||

| 0.05 | forgetting factor | ||

| 0.008 | boundary-layer thickness | ||

| 7.5 × 108 | linear gain |

| Performance Metrics | Switching Controller | Controller A | Controller B | PID Controller | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Stage | Maximum Displacement Error | 6.944 mm | 23.619 mm | 10.320 mm | 36.122 mm |

| Velocity Peak-to-Peak Fluctuation | 0.138 m/s | 0.138 m/s | 0.878 m/s | 0.050 m/s | |

| Spool-Displacement Peak-to-Peak Fluctuation | 0.202 mm | 0.202 mm | 0.811 mm | 0.360 mm | |

| Stable Stage | Maximum Displacement Error | 7.599 mm | 201.86 mm | 6.455 mm | 38.756 mm |

| Velocity Peak-to-Peak Fluctuation | 0.011 m/s | 0.017 m/s | 0.017 m/s | 0.011 m/s | |

| Spool-Displacement Peak-to-Peak Fluctuation | 0.028 mm | 0.200 mm | 0.045 mm | 0.029 mm | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, S.; Han, D.; Jiang, L.; Jia, L.; Zheng, Z.; Tan, X.; Yang, H.; Hu, D. A Two-Phase Switching Adaptive Sliding Mode Control Achieving Smooth Start-Up and Precise Tracking for TBM Hydraulic Cylinders. Actuators 2026, 15, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010057

Yang S, Han D, Jiang L, Jia L, Zheng Z, Tan X, Yang H, Hu D. A Two-Phase Switching Adaptive Sliding Mode Control Achieving Smooth Start-Up and Precise Tracking for TBM Hydraulic Cylinders. Actuators. 2026; 15(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Shaochen, Dong Han, Lijie Jiang, Lianhui Jia, Zhe Zheng, Xianzhong Tan, Huayong Yang, and Dongming Hu. 2026. "A Two-Phase Switching Adaptive Sliding Mode Control Achieving Smooth Start-Up and Precise Tracking for TBM Hydraulic Cylinders" Actuators 15, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010057

APA StyleYang, S., Han, D., Jiang, L., Jia, L., Zheng, Z., Tan, X., Yang, H., & Hu, D. (2026). A Two-Phase Switching Adaptive Sliding Mode Control Achieving Smooth Start-Up and Precise Tracking for TBM Hydraulic Cylinders. Actuators, 15(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010057