1. Introduction

As a primary medium for the existence, transmission, and expression of information, sound serves as an important tool for social interaction and the exchange of ideas in various scenarios. Voice data contains a significant amount of sensitive information. The development of effective security measures for protecting this sensitive sound information, particularly in critical scenarios involving national security and commercial confidentiality, constitutes a persistent challenge [

1,

2]. Preventing voice data leakage remains a critical and unsolved problem.

Acoustic eavesdropping is a surveillance technique that acquires sound by directly capturing it or by obtaining vibration information [

3]. According to the differences in the types of devices used, acoustic eavesdropping technology that captures the vibration information of objects can be classified into the following three categories: acoustic eavesdropping based on accelerometers or piezoelectric sensors, acoustic eavesdropping based on optical sensors, and acoustic eavesdropping based on radio frequency [

4]. The first type of technology uses sensors to capture the slight vibrations of objects caused by sound, converting mechanical vibration signals into analyzable electrical signals to restore voice information. It has the characteristics of being non-contact and capable of remote monitoring [

5]. The second type of technology uses optical devices to capture the optical changes caused by the vibrations on the surface of objects induced by sound. The results obtained using this method are more accurate and suitable for long-distance acoustic eavesdropping [

6]. The third type of technology uses the reflection characteristics of radio waves to obtain the vibration information of objects, offering advantages such as strong penetration and long detection range [

7]. In conclusion, the fundamental principle of these three types of technologies is to capture the minute vibrations generated by the target object under the influence of the sound field, and then restore the captured vibration signals into sound after amplification and filtering.

For example, a laser eavesdropper is a typical application of acoustic eavesdropping technology. Its working principle is as follows: a laser beam is emitted to the target object (such as window glass or the surface of the table). Vibrations cause changes in the phase or intensity of the reflected light. The receiver analyzes these changes in the reflected light to obtain the vibration signals of the target object under the influence of sound waves. The sound is then restored through decoding, thus achieving the purpose of eavesdropping [

8]. Xu et al. developed a laser eavesdropping technology that can listen remotely. By installing a miniature signal amplifier inside the laser cavity, it is possible to capture the faint vibration signals of target objects from over 200 m away, thereby enabling the restoration and recognition of sound [

9]. In addition, the effective distance for recognizing and restoring speech information can be extended to the kilometer range, making it an advanced eavesdropping method with strong concealment, ease of operation, and difficulty in being detected [

10,

11]. Therefore, preventing the vibration generated by the target object under the influence of the sound field from being detected has become an urgent problem that needs to be solved.

With the widespread application and continuous development of laser eavesdropping technology, corresponding interference methods have also gradually developed. Depending on operational scenarios and implementation mechanisms, interference technologies can be divided into two main categories: active and passive. Passive interference technology is mainly implemented through the following methods: increasing the thickness of objects such as walls and glass, changing the material properties of objects, and optimizing the structure of objects. For example, using materials with absorption and scattering properties to cover an object can effectively reduce the reflected light signal received by the laser eavesdropping equipment [

12]. Zeng et al. studied the effects of glass thickness, size, and number of layers on glass vibration. The results showed that when the size and thickness are the same, hollow double-layer glass can effectively reduce glass vibration compared to single-layer glass [

13]. However, the above methods require modifications to the structure of the building or object, or require time and resources to implement, making them unsuitable for scenarios that require rapid deployment or portable facilities. Active interference technology mainly includes sound masking technology. Sound masking technology is based on the auditory masking effect of the human ear, which refers to the phenomenon where the presence of one sound raises the auditory threshold of another sound, making it harder to hear [

14,

15]. By applying air sound masking or vibration sound masking to structures like doors, windows, and pipes, thereby improving the confidentiality performance of the facilities and spaces [

16]. For example, Kim et al. studied a sound masking actuator. By analyzing the impact of the vibration interference generated by the exciter on the clarity of the restored sound, the results showed that the vibration interference produced by this exciter can effectively prevent the restoration of sound [

17]. By installing sound masking speakers on the ceiling or beneath the floor, noise with a masking effect can be generated within a certain area. This method effectively interferes with the acquisition of the target object’s vibration signals, thereby achieving the effect of protecting privacy [

18]. Active interference technology is a method that can take effect quickly, but directly using speakers for sound masking can affect indoor comfort. In addition, existing technologies that utilize vibration and anti-acoustic methods for eavesdropping are difficult to meet the requirements for rapid deployment. Therefore, sound masking structures with the characteristics of portability and the ability to achieve rapid deployment have become the key focus of current research.

Among the various methods using vibration interference for anti-acoustic eavesdropping, conventional exciters often struggle to achieve high-frequency excitation, and the size of electromagnetic actuators is usually too large [

19]. However, as a type of smart material, piezoelectric materials have been widely used in fields such as precision driving and vibration control due to their lightweight, wide frequency response, and ease of integration [

20,

21,

22]. In recent years, researchers have begun to explore the integration of piezoelectric materials into flexible substrates to construct lightweight, deformable, and low-power active vibration control devices, providing a new technological pathway for anti-acoustic eavesdropping [

23,

24]. For example, Wang et al. designed a PVDF piezoelectric film that is lightweight and has good mechanical flexibility, addressing the fragility of piezoelectric ceramic sheets, and it has been successfully applied in the field of hydrophones [

25]. However, such piezoelectric film actuators have low output force and perform poorly when used for active vibration interference. Additionally, many studies have designed acoustic eavesdropping systems that respond to sound pressure changes using the piezoelectric effect of piezoelectric materials, and this system can effectively recover indoor human voices [

26,

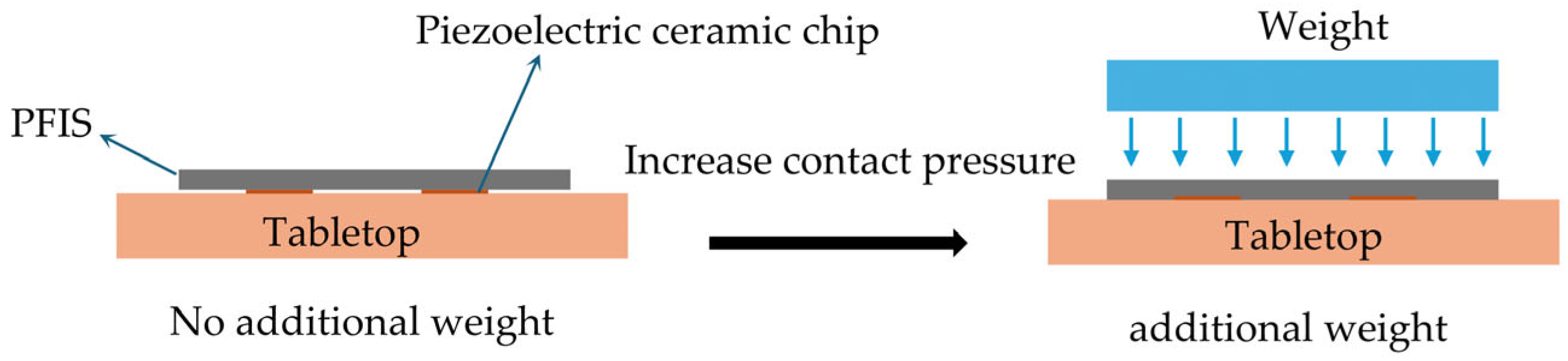

27]. However, there are a few cases of using piezoelectric materials for anti-vibration acoustic eavesdropping. Therefore, the major contribution of this paper lies in the design of a piezoelectric flexible interference structure (PFIS), providing a novel and practical technical solution for active interference technology against anti-vibration acoustic eavesdropping. Compared to the traditional approach of directly adhering piezoelectric elements to the structure, this paper enhances the contact pressure of the PFIS by adding weight to achieve effective vibration transmission while also enabling rapid deployment and recovery. In addition, this paper experimentally studied the vibration interference capability of PFIS on a wooden board under three different sound signals compared to a human voice, and analyzed the recognizability of the speech content obtained from the vibration information of the wooden board.

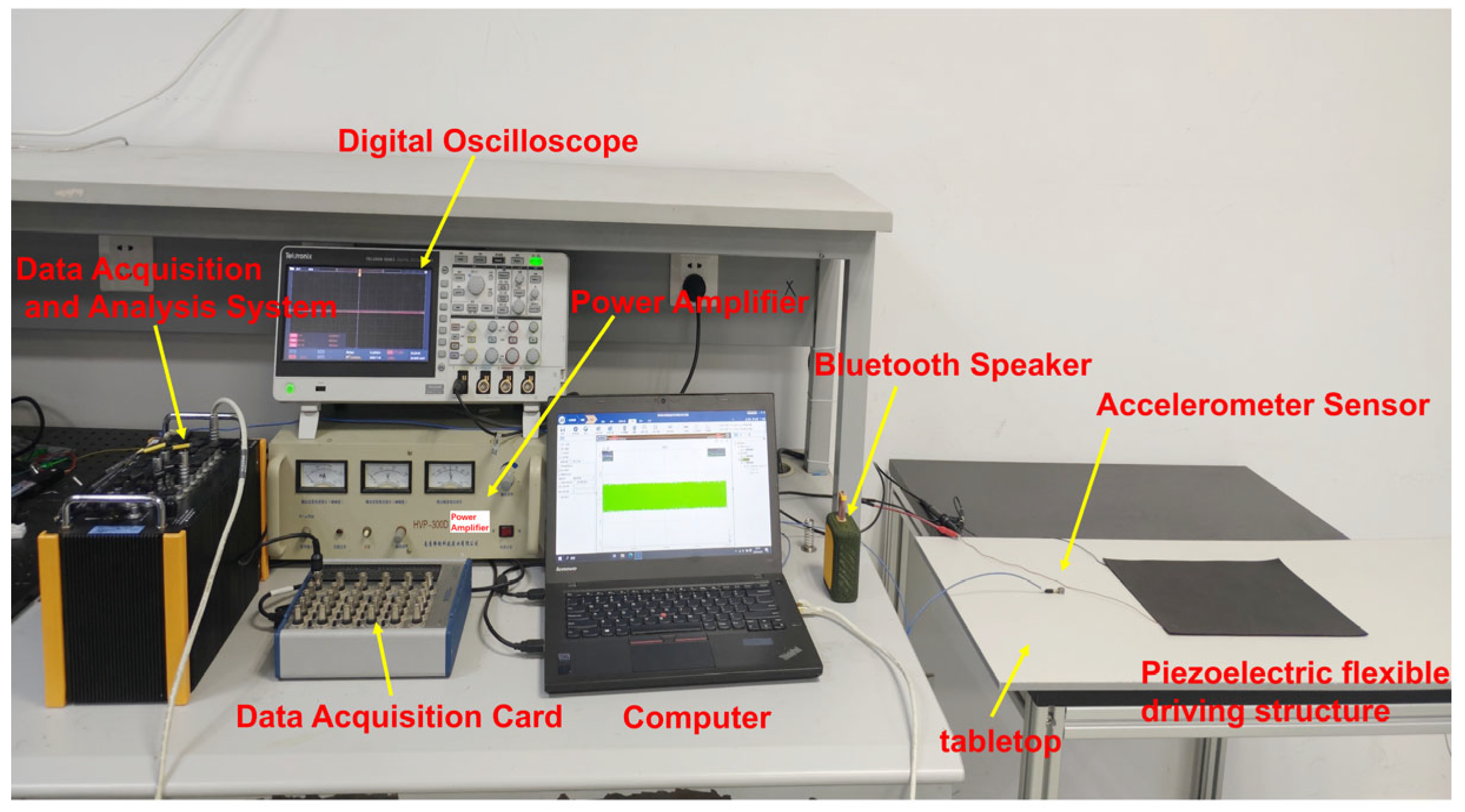

2. Design and Principle of the PFIS

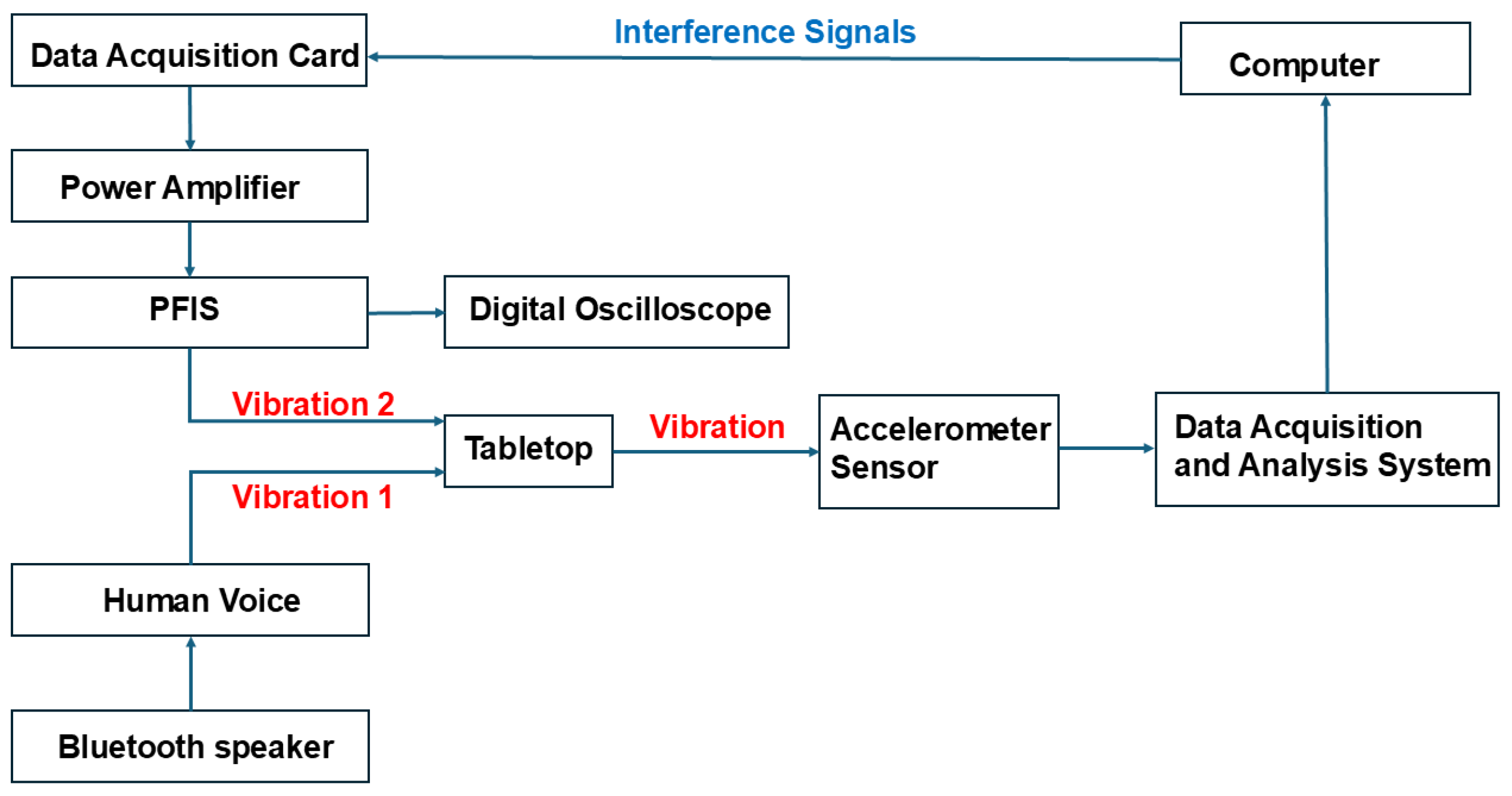

Typically, in some rapidly deployed temporary meeting venues, information security measures are often ignored. The PFIS in this paper features excellent flexibility and lightweight characteristics, providing information security protection measures in rapidly deployed facilities. The PFIS consists of a signal output system, a power amplification system, and a piezoelectric actuator structure. The working principle of using PFIS for active vibration interference to achieve anti-laser eavesdropping is shown in

Figure 1. Firstly, the signal output system generates interference signals with different sounds. Then, the interference signals are amplified by the power amplification system and output as the corresponding driving voltage. Next, the piezoelectric actuator structure generates vibration interference on target objects such as the tabletop. Finally, the vibration generated by PFIS masks the vibrations caused by a human voice on the target object, making the voice content restored from the vibrations unrecognizable.

The active vibration generated by the PFIS comes from its four piezoelectric ceramic plates. When a driving voltage is applied, the ceramic plates produce strain in the thickness direction due to the inverse piezoelectric effect, thereby exciting vibrations. The main excitation mode of the piezoelectric ceramic plates is the thickness vibration mode. To describe its electromechanical response process, we use a linear piezoelectric constitutive equation for simplified analysis. For vibrations in the thickness direction, the constitutive relationship can be expressed as

where

is the strain in the thickness direction,

is the stress in the thickness direction,

is the electric field strength in the thickness direction, and

is the electric displacement.

is the short-circuit elastic compliance constant,

is the piezoelectric strain constant, and

is the free dielectric constant.

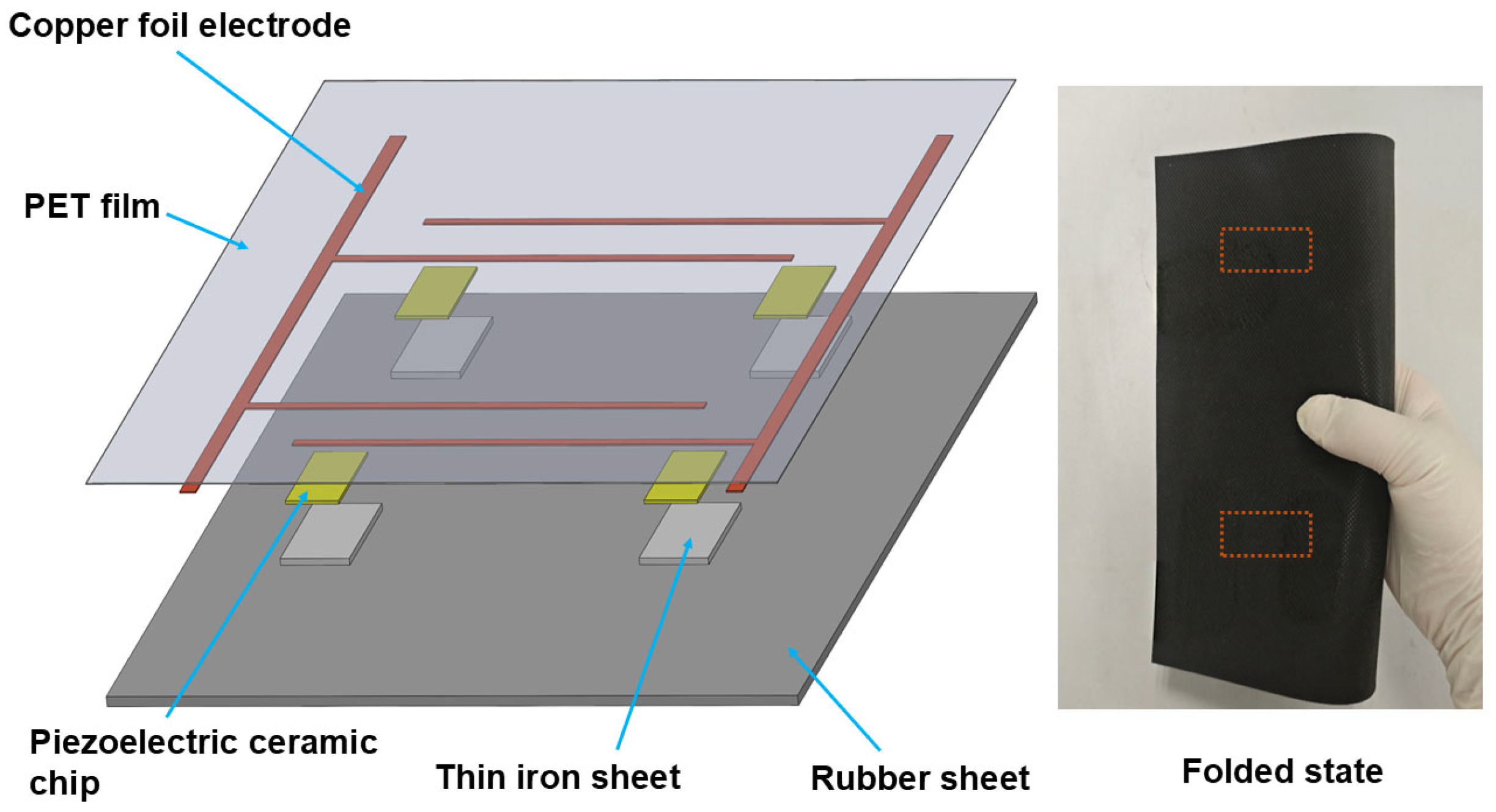

The composition of the piezoelectric actuator structure designed in this paper and its schematic in the folded state are shown in

Figure 2. It is composed of a rectangular rubber plate, a thin iron sheet, a piezoelectric ceramic sheet, a copper foil electrode, and a PET film, arranged from bottom to top.

Table 1 shows the geometric parameters of each component of the PFIS. PFIS has a rubber at the bottom, which provides certain flexibility. It can be folded or bent during transportation, serving a portable function. The thin iron sheet compensates for the deficiencies of the piezoelectric ceramic in terms of strength and brittleness, significantly enhancing its resistance to damage when folded or bent. The PET film serves as the encapsulation layer, covering the surface of the piezoelectric actuator structure, further enhancing the overall structure’s applicability and durability. The PFIS is directly placed on the floor or in the pipeline during use, without being adhered to the structure. This method facilitates quick deployment and retrieval, increasing the possibility of reuse. Additionally, a layer of PET protective film is added over the piezoelectric chip and copper foil electrode to protect the key components inside, thereby preventing damage to these components during dragging and movement, which enhances the durability of the structure. After multiple uses and folding, the PFIS can also maintain its good working performance by replacing the rubber base and the PET protective film. The type of piezoelectric ceramic used in the PFIS is PZT-5, with a free dielectric constant

and a piezoelectric strain constant

. Its supplier is Harbin Core Tomorrow Technology Co., Ltd. in Harbin, China, and the overall capacitance of the PFIS made from this piezoelectric ceramic is 264 nF.

4. Performance Analysis of Vibration Interference

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is an important parameter for measuring signal quality, representing the ratio of the power of the useful signal to the power of the noise signal [

28]. SNR has wide applications in signal processing fields such as communication, audio processing, and video processing. SNR is defined as the ratio of signal power to noise power, typically expressed in decibels (dB). Its formula is

where

represents the signal power, which is the signal data measured in an environment without noise.

represents the noise power, which is the signal data measured in the presence of noise. If the signal and noise sampling values are

and

, respectively, the signal and noise power can be calculated using the following formulas:

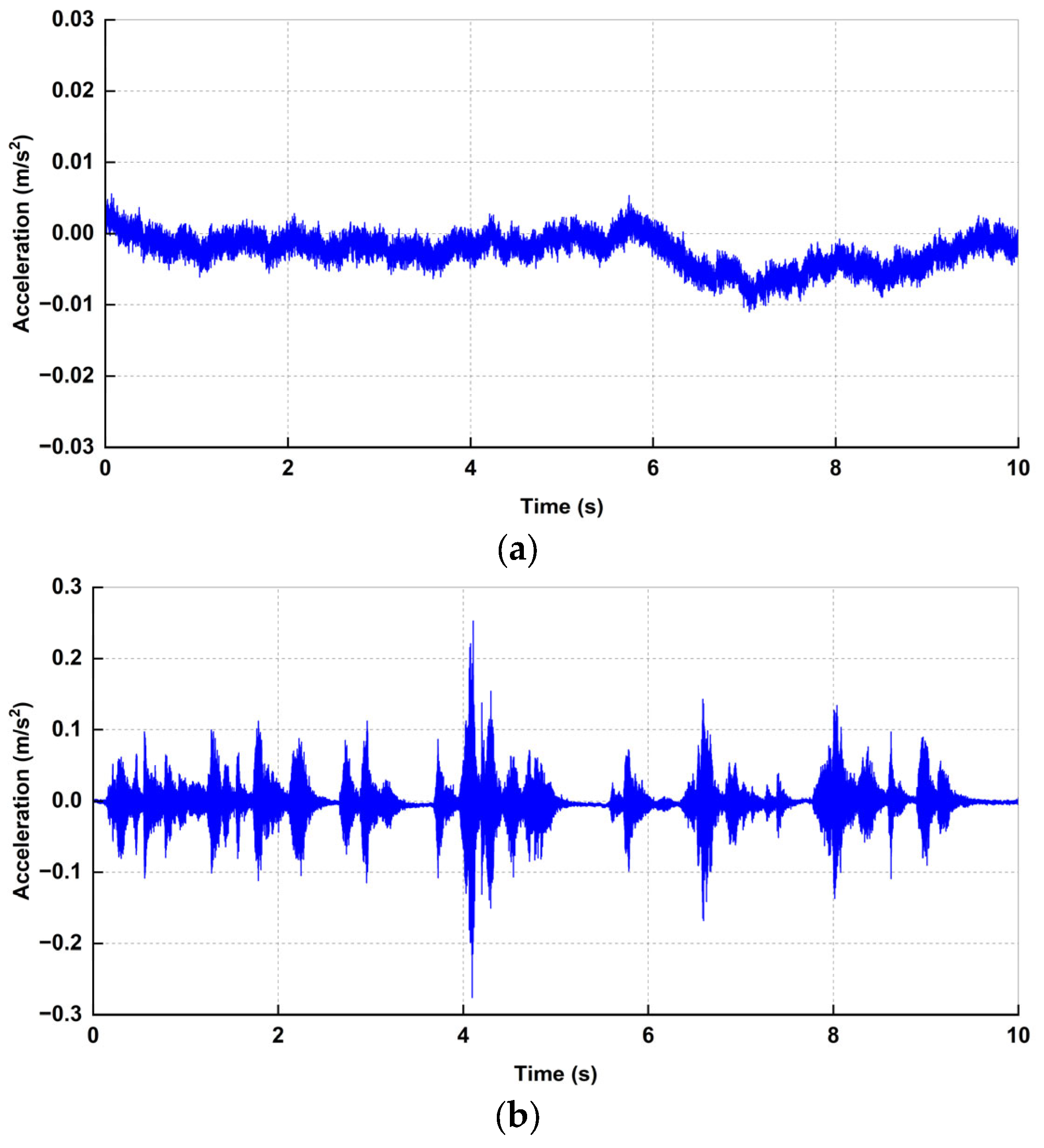

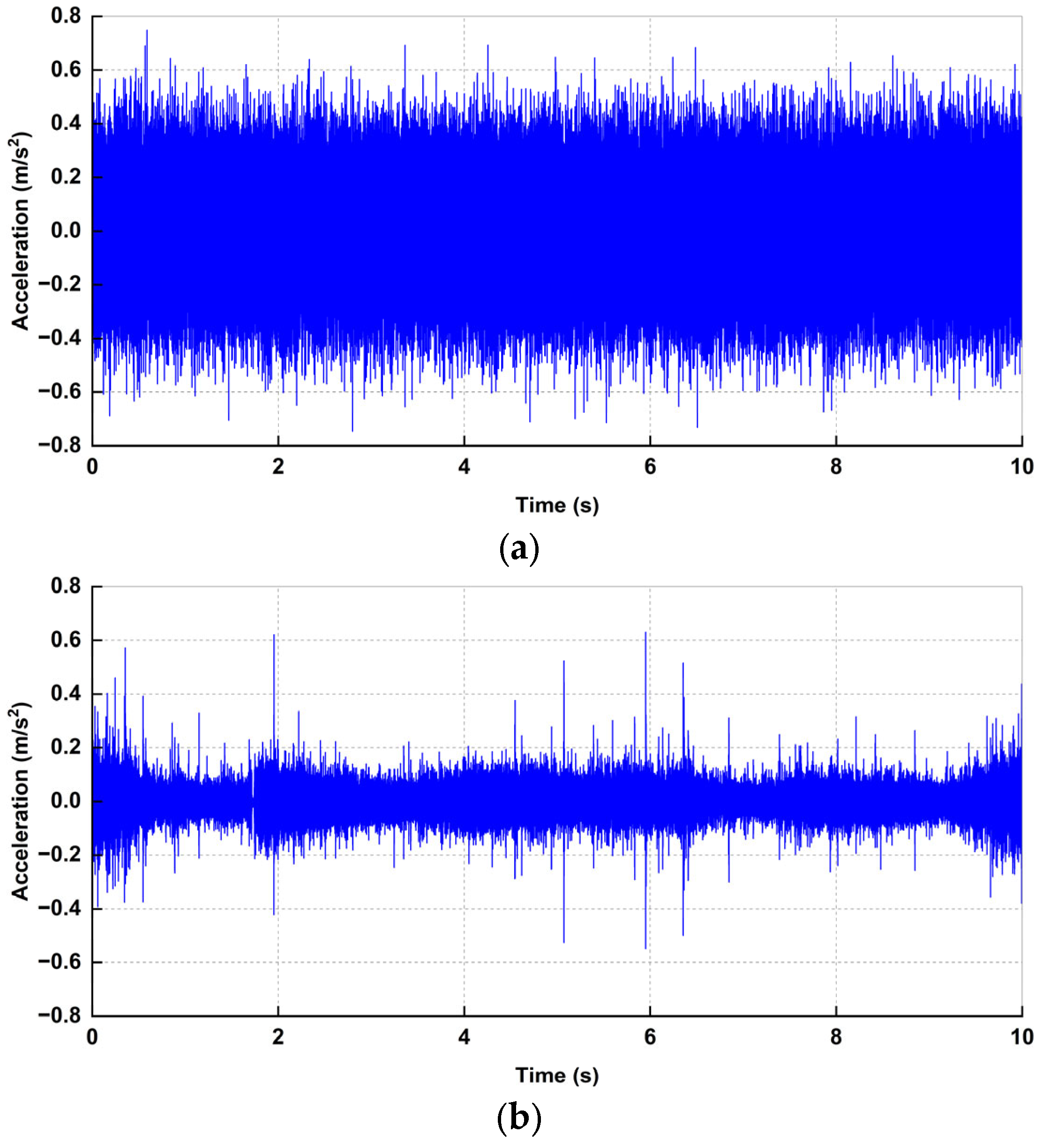

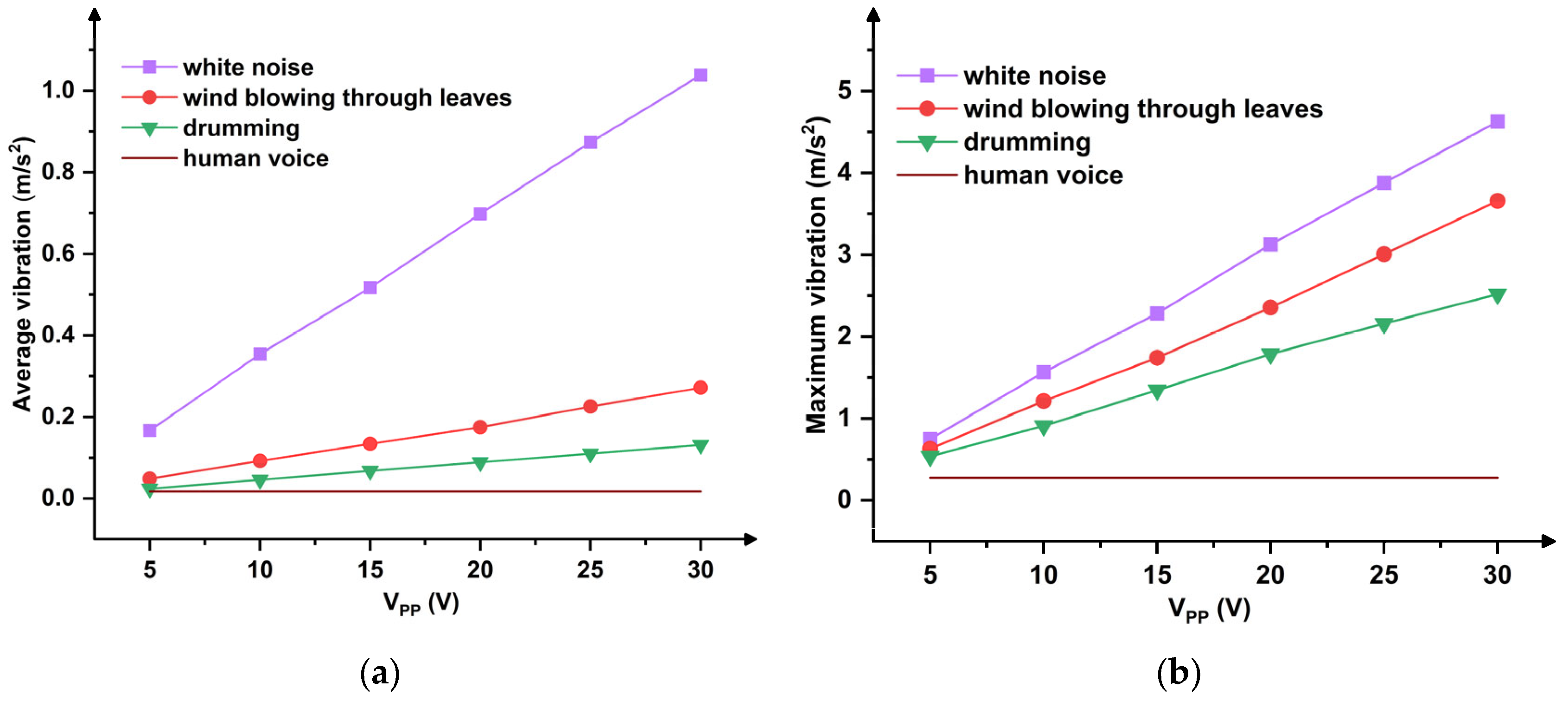

By analyzing the vibration interference generated by the PFIS on the surface of the table, the sound masking performance of the PFIS is explored. First, with no interference, the Bluetooth speaker is turned on to play human voices. The vibration acceleration of the surface of the table caused by the human voice at this moment is measured and recorded as the reference signal. Then, sound signals with different driving voltages are applied under the conditions of 3.5 kg of additional weight and no additional weight. The vibration acceleration of the surface of the table caused by the PFIS at this moment is measured and recorded as the interference signal. In this experiment, the calculated SNR ≤ 0 indicates that the power of the interference signal exceeds the power of the reference signal, indicating that the generated vibration interference is effective. Moreover, the smaller the SNR, the stronger the vibration interference effect.

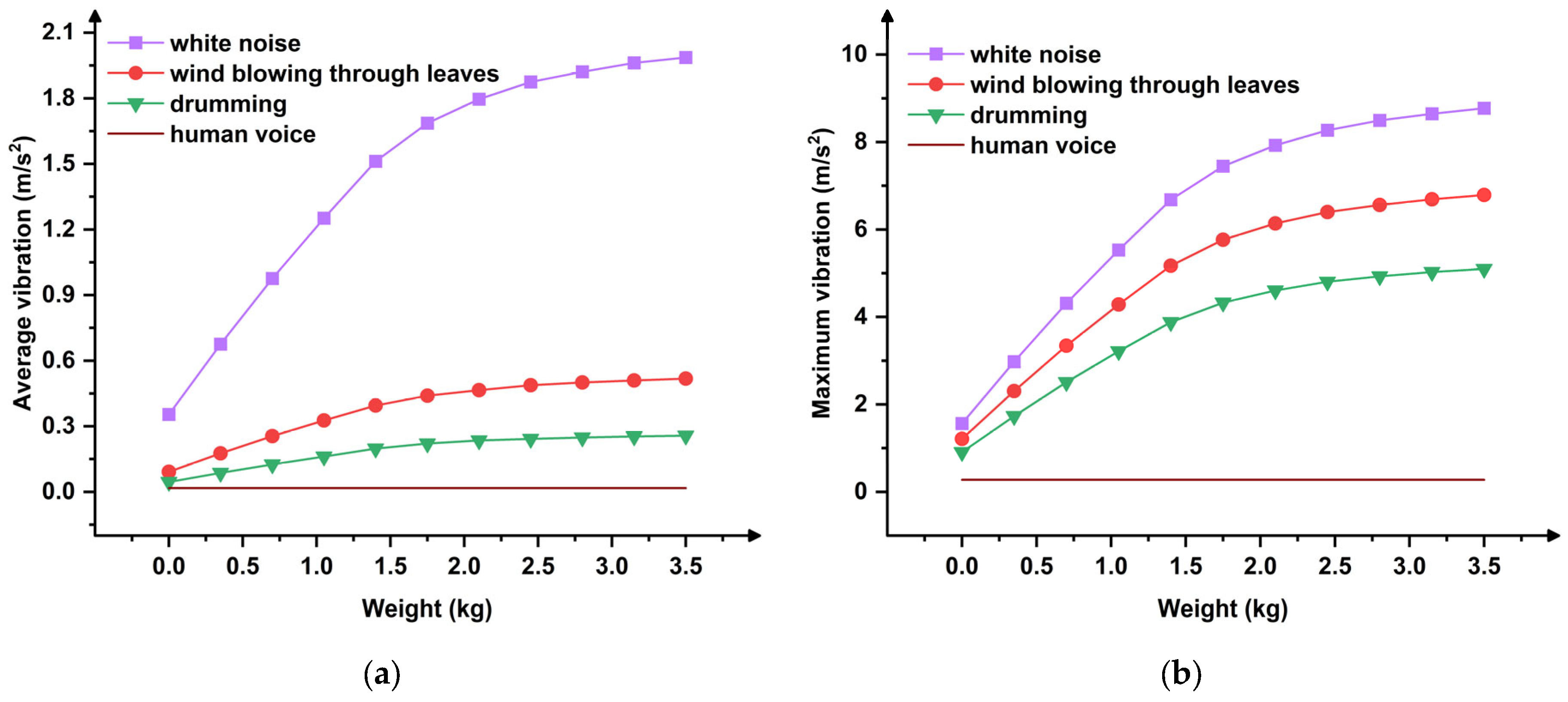

Under two conditions, without additional weight and with an additional weight of 3.5 kg, the SNR for different interference and reference signals at various voltages is calculated based on the experimentally measured data.

Figure 13 shows the SNR with different interference and reference signals applied under different voltages, both with and without an additional weight of 3.5 kg.

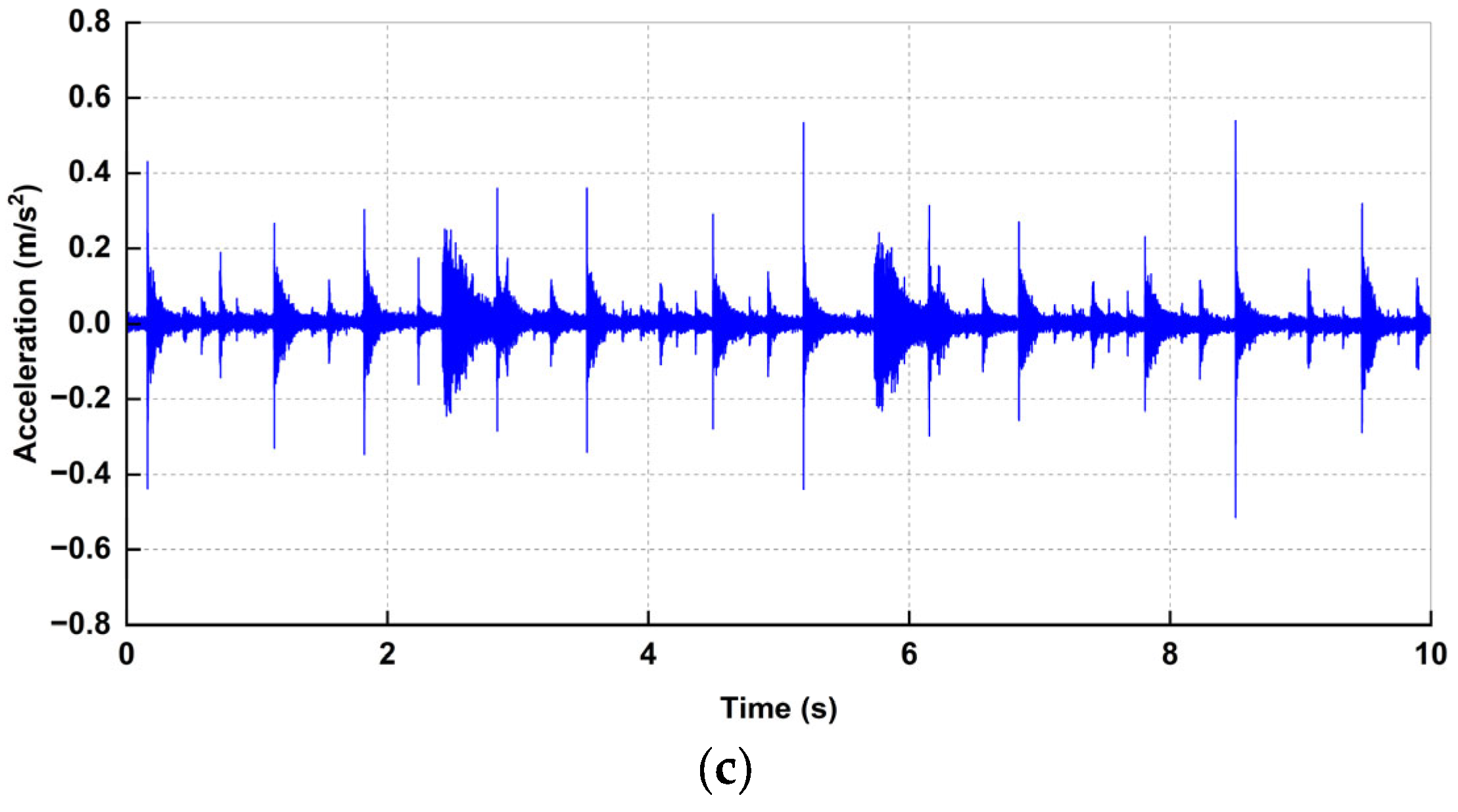

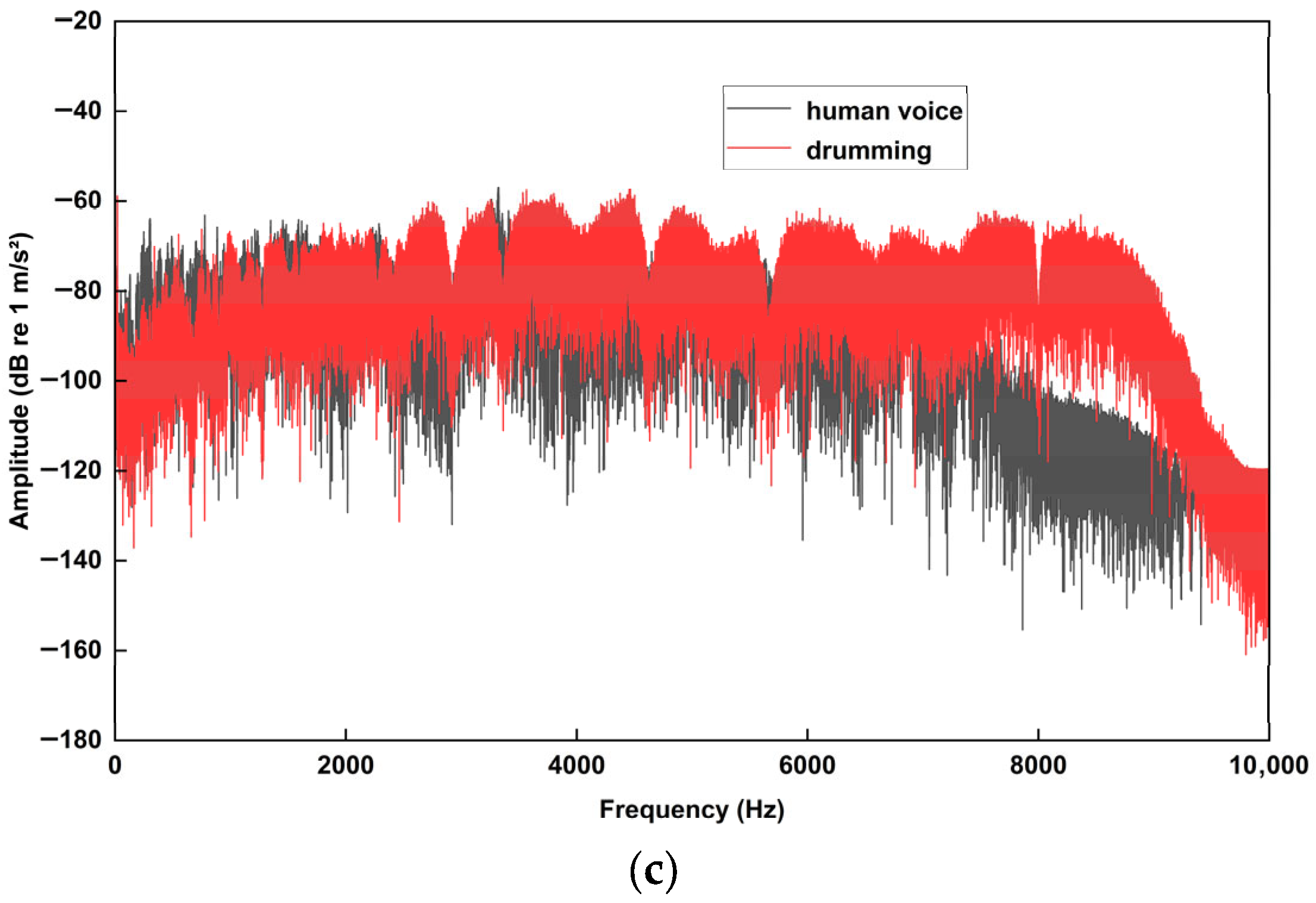

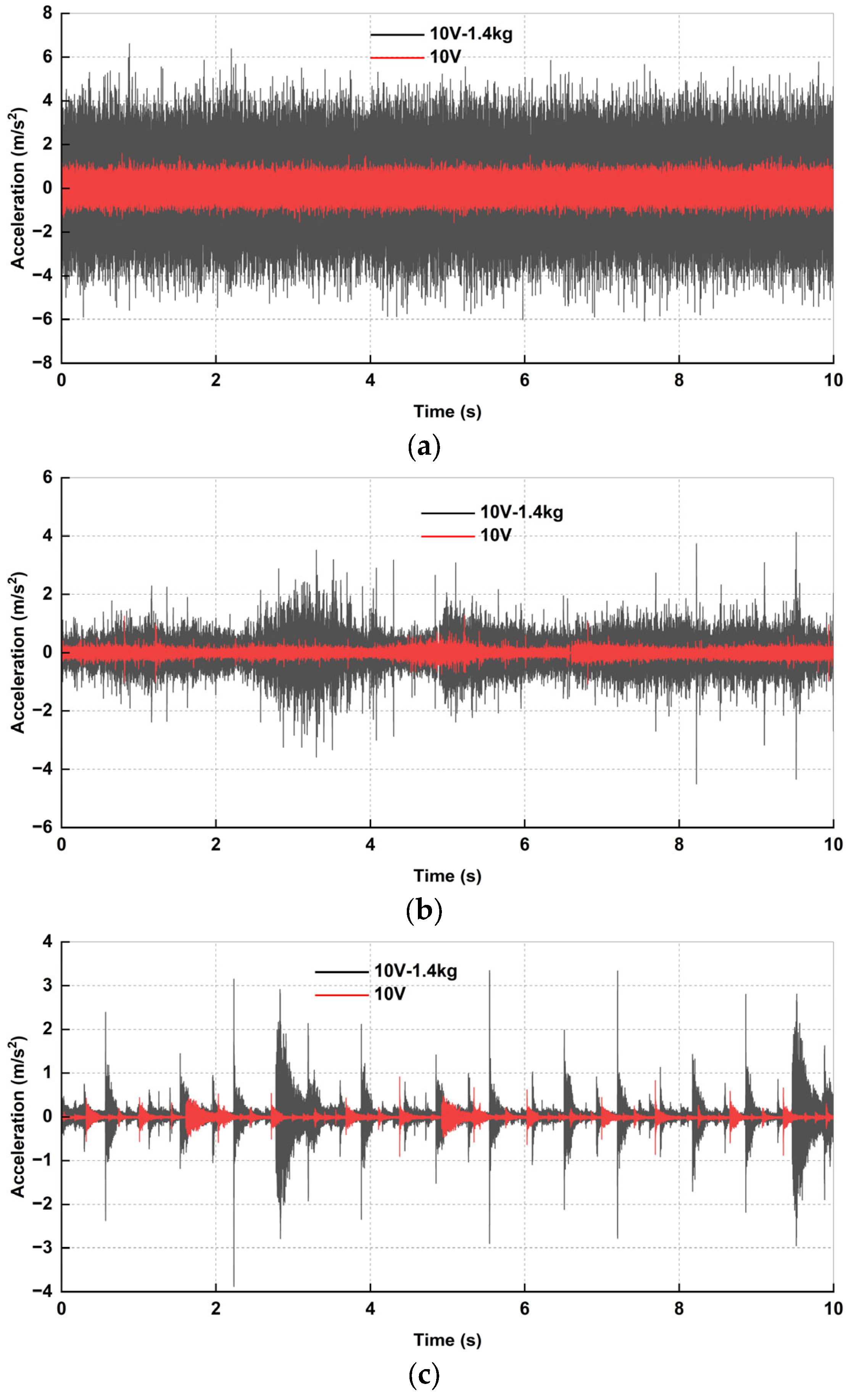

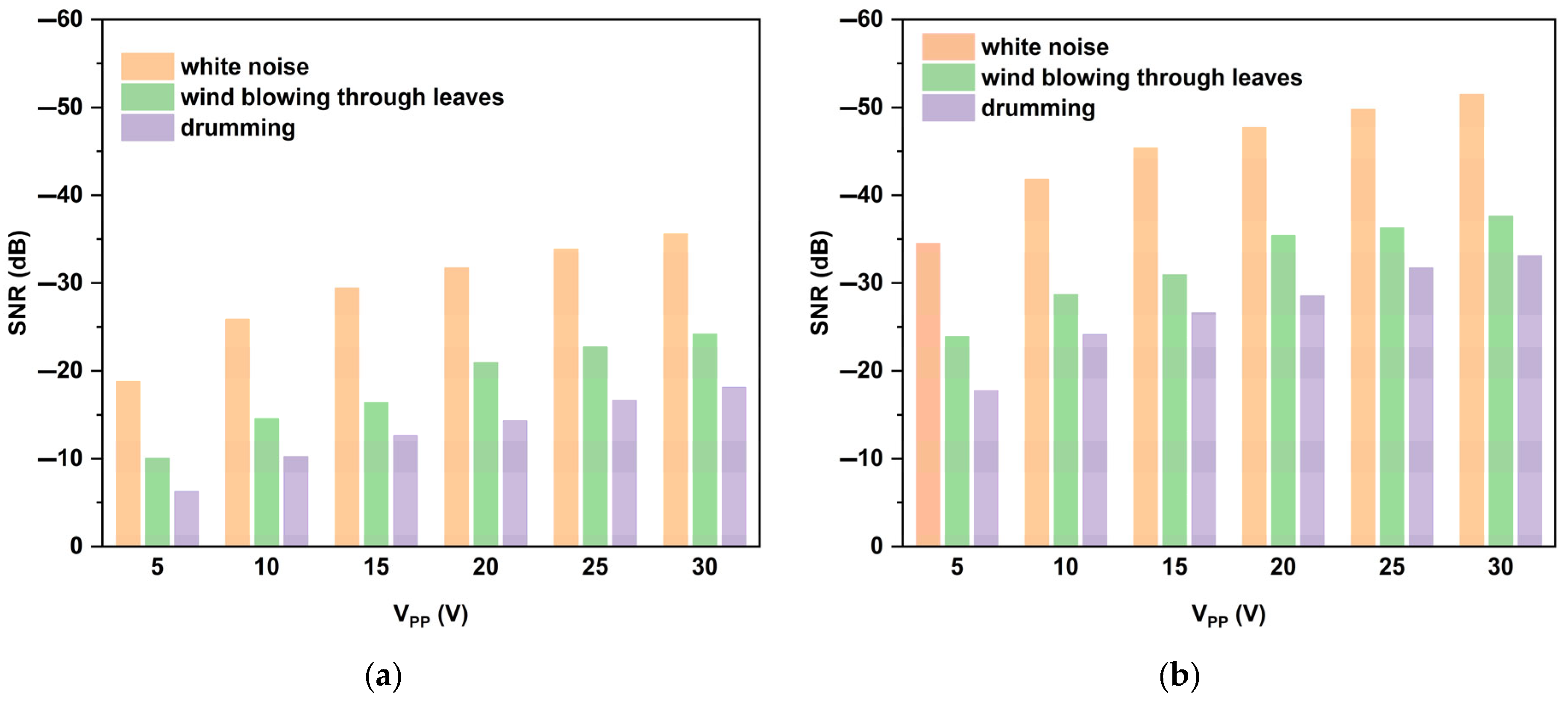

The results showed that under different experimental conditions, the noise power of each interference signal exceeds the power of the reference signal, indicating that the vibration interference of the PFIS plays a role in sound masking. However, the SNR cannot reveal the impact of the driving voltage and added weight on vibration interference performance across different frequency ranges. To explore the relationship between noise and signal in terms of frequency, the Welch method is used to estimate the power spectral density (PSD) of the interference signal and the reference signal. For example, in the case of no additional weight and with an additional weight of 3.5 kg, the PSD comparison of different interference signals and reference signals is obtained under the peak-to-peak voltage of 5 V and 30 V, as shown in

Figure 14. Here, the white noise, the sound of wind blowing through leaves, and the sound of drumming are referred to as interference signal 1, interference signal 2, and interference signal 3, respectively. The PSD is computed using Welch’s method and is expressed in decibels (dB) relative to 1 (m/s

2)

2/Hz.

It can be seen from

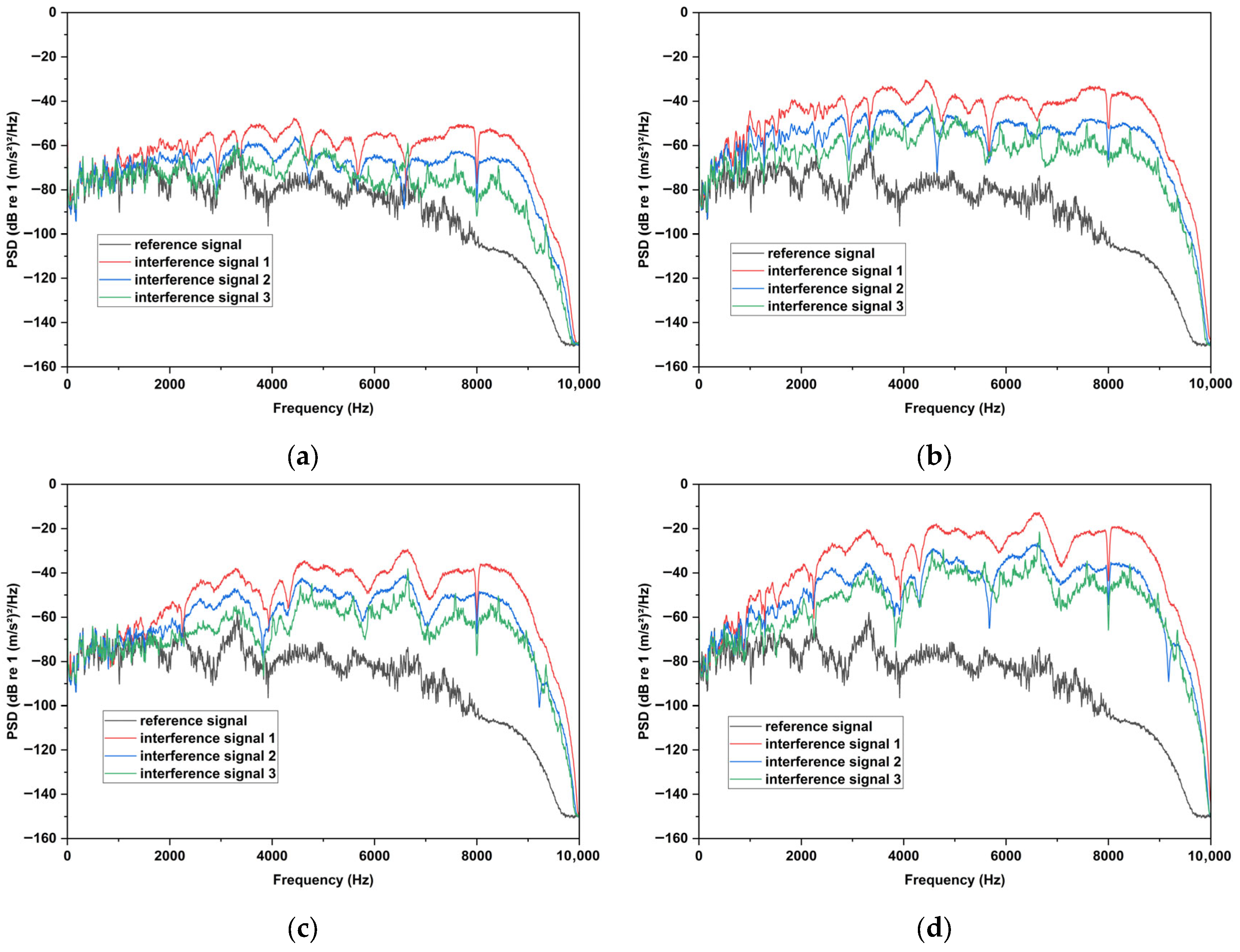

Figure 14 that, after the frequency exceeds 2500 Hz, both increasing the voltage and adding weight to the surface of the piezoelectric actuator structure can significantly improve the vibration interference performance of PFIS. However, when the frequency is below 2500 Hz, the discrepancy in power between the interference signal noise and the reference signal power is not significant. In some frequency ranges, the PSD of the reference signal is even greater than that of the interference signal. In order to better study the vibration interference performance in the low-frequency stage,

Figure 15 analyzes the comparison of the PSD of the reference signal and the interference signal in the frequency range of 0–3500 Hz. The results showed that when the voltage increases, the vibration interference performance of the PFIS under the interference signal can be significantly improved in the low-frequency range. When the frequency is below 2500 Hz, the added weight does not significantly improve the vibration interference performance of the PFIS. However, after 2500 Hz, the added weight can significantly enhance the vibration interference performance of the PFIS. In conclusion, increasing the driving voltage can improve the vibration interference performance of the PFIS across the entire frequency range. After adding the weight, the vibration interference performance of the PFIS can be significantly improved when the frequency is greater than 2500 Hz.

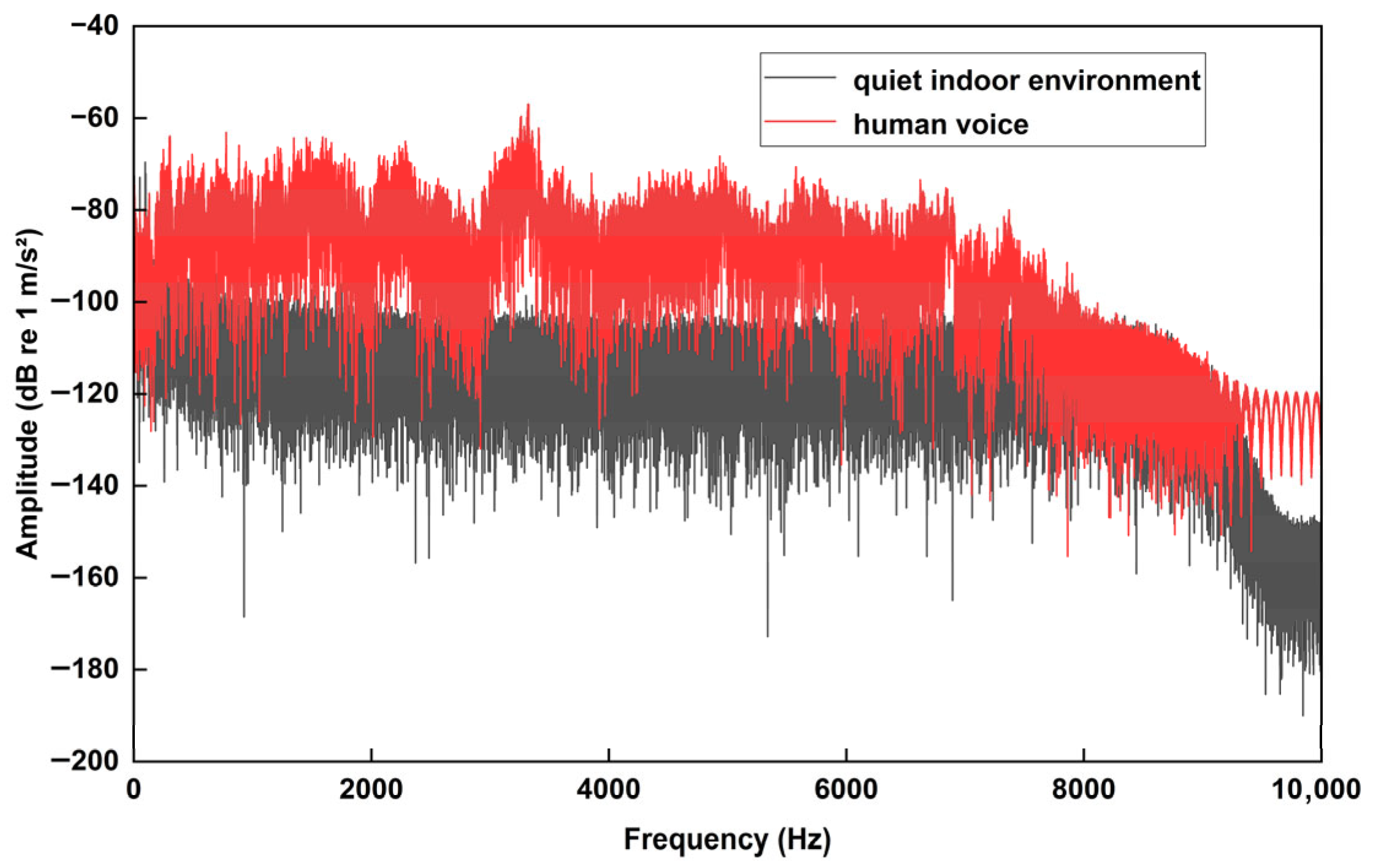

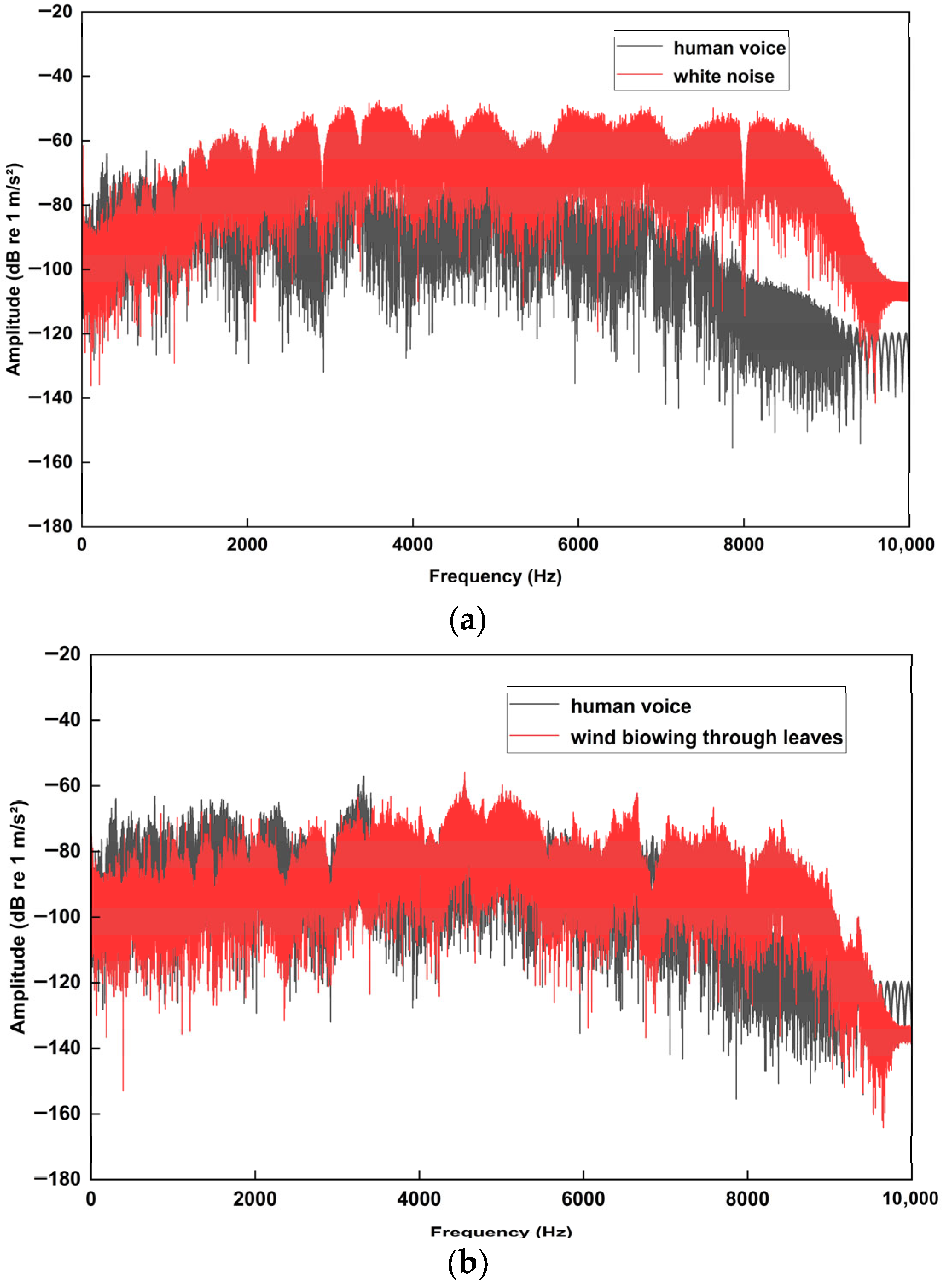

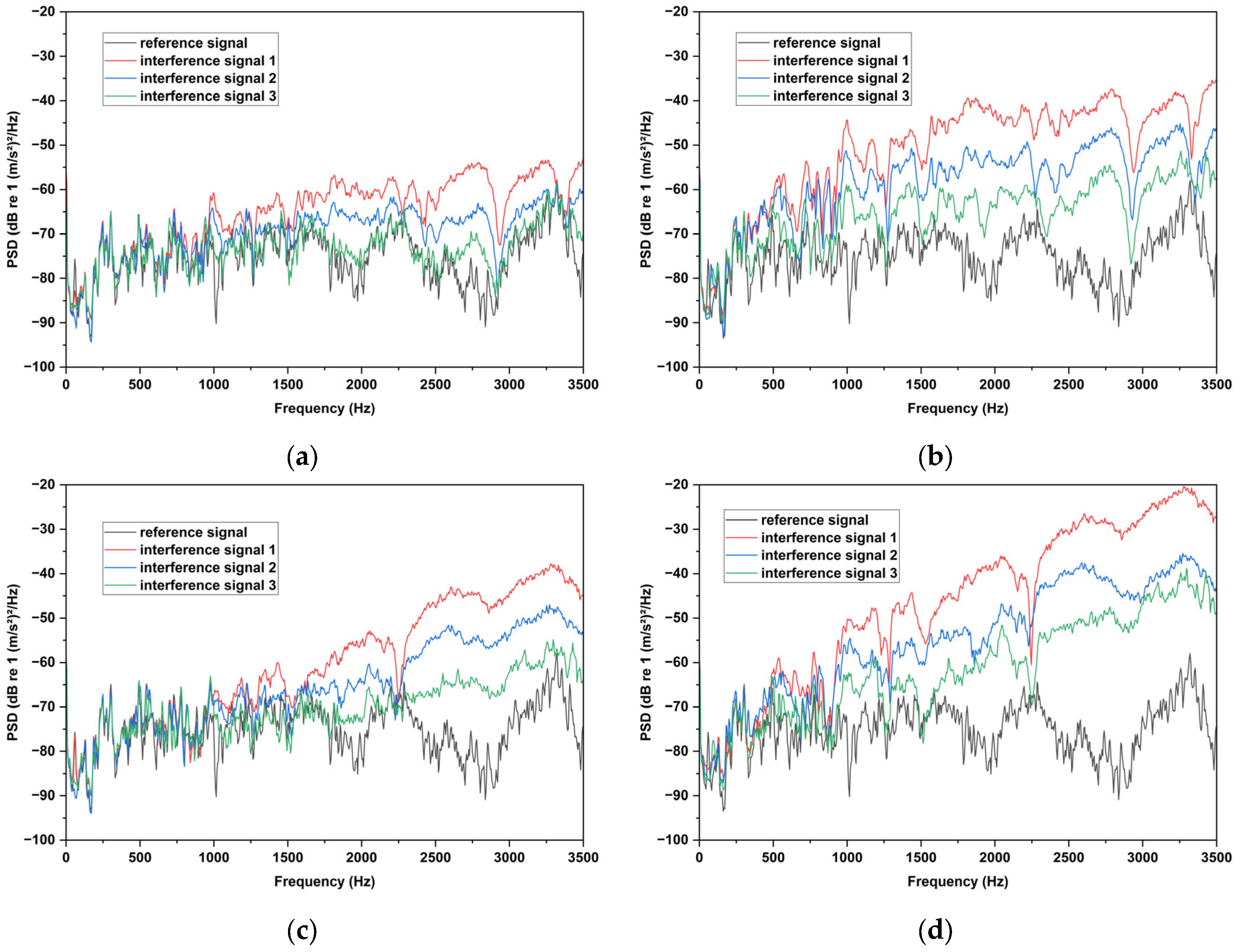

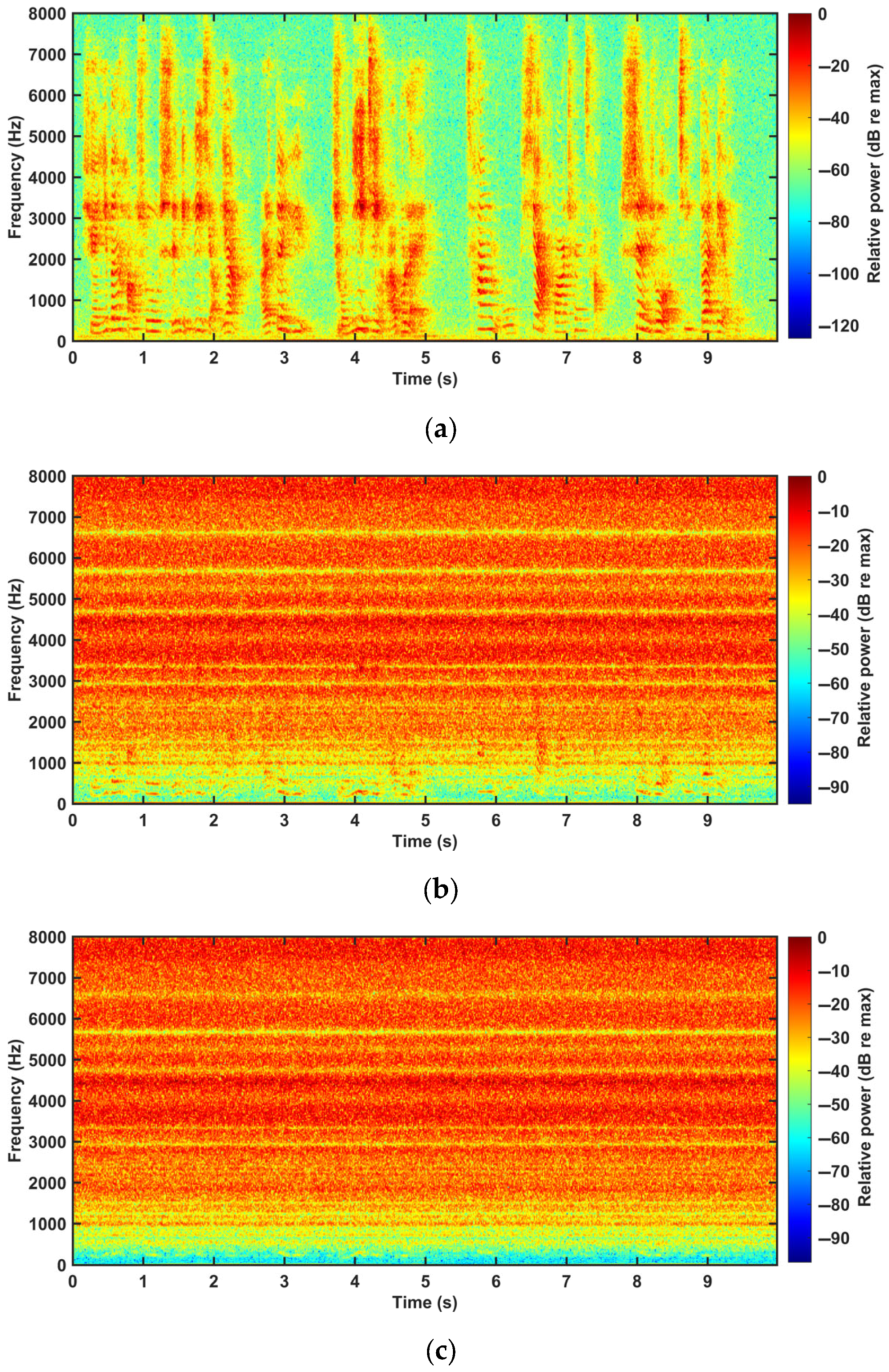

Next, analyze the masking effect of PFIS on vibration restoration sounds from the perspective of the speech spectrum. First, in the previous experiment, the Bluetooth speaker was set to loop a 10 s audio of a person speaking. Measure the 20 s vibration data on the surface of the table under the condition of human voice. Then, decode the measured vibration information to restore it to audio. Finally, use Adobe Audition to edit the audio, obtaining a 10 s human voice audio with the timeline aligned. The processed audio has a frequency of 16,000 Hz and is output in mono. Similarly, the Bluetooth speaker continues to play the human voice. Under the conditions of peak-to-peak voltage of 5 V and 30 V, the PFIS uses white noise signals to induce vibration interference on the surface of the table. Then, the 10 s interference audio with time axis alignment is obtained. Finally, the speech spectrograms for the three cases are shown in

Figure 16. From the analysis of the speech spectrogram, it can be observed that in the case where only human voice is present, the voiceprint of the human sound can be clearly seen in the restored speech spectrogram, and the speech content is fully discernible. Under the condition of a 5 V peak-to-peak voltage with white noise signal interference, it can be seen that most of the voiceprint of the human sound is masked. However, within the frequency range of 0–2500 Hz, some of the voiceprint still remains. Under the conditions of a peak-to-peak voltage of 30 V with white noise signal interference, the voiceprint of the human voice is almost completely covered. This is consistent with the results obtained using the PSD method for analysis. When the driving voltage increases, it can improve the vibration interference performance of the interference structure across the entire frequency range, including at lower frequencies. However, when the frequency is below 2500 Hz, the addition of weight does not significantly improve the vibration interference performance of the PFIS. According to the conclusion, below 2500 Hz, the vibration interference performance of the PFIS is limited. To address this issue, subsequent optimization of the interference can be achieved by altering the amplitude of the interference signal below 2500 Hz or by adjusting the amplitude of the interference signal at different frequencies.