Extenics Coordinated Torque Distribution Control for Distributed Drive Electric Vehicles Considering Stability and Energy Efficiency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

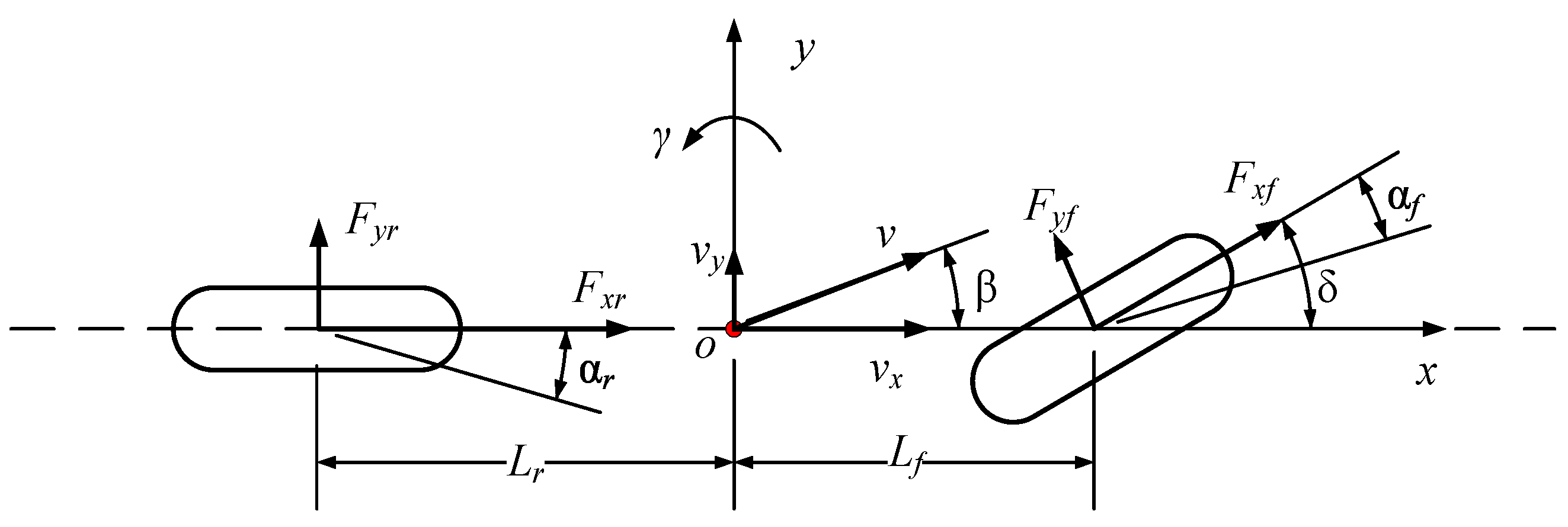

2.1. Two-Degree-of-Freedom Mathematical Model of Vehicle Dynamics

2.1.1. Nonlinear Two-Degree-of-Freedom Vehicle Dynamics Model

2.1.2. Two-Degree-of-Freedom Linear Vehicle Dynamics Model

2.1.3. Reference Model

2.2. Research on Vehicle Motion Control Methods

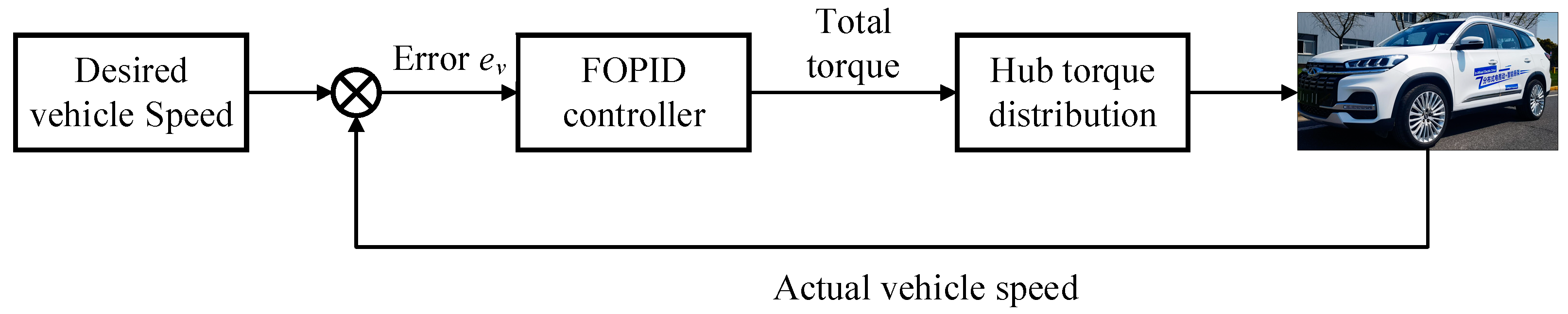

2.2.1. Longitudinal Speed Tracking Control

2.2.2. Vehicle Lateral Stability Control

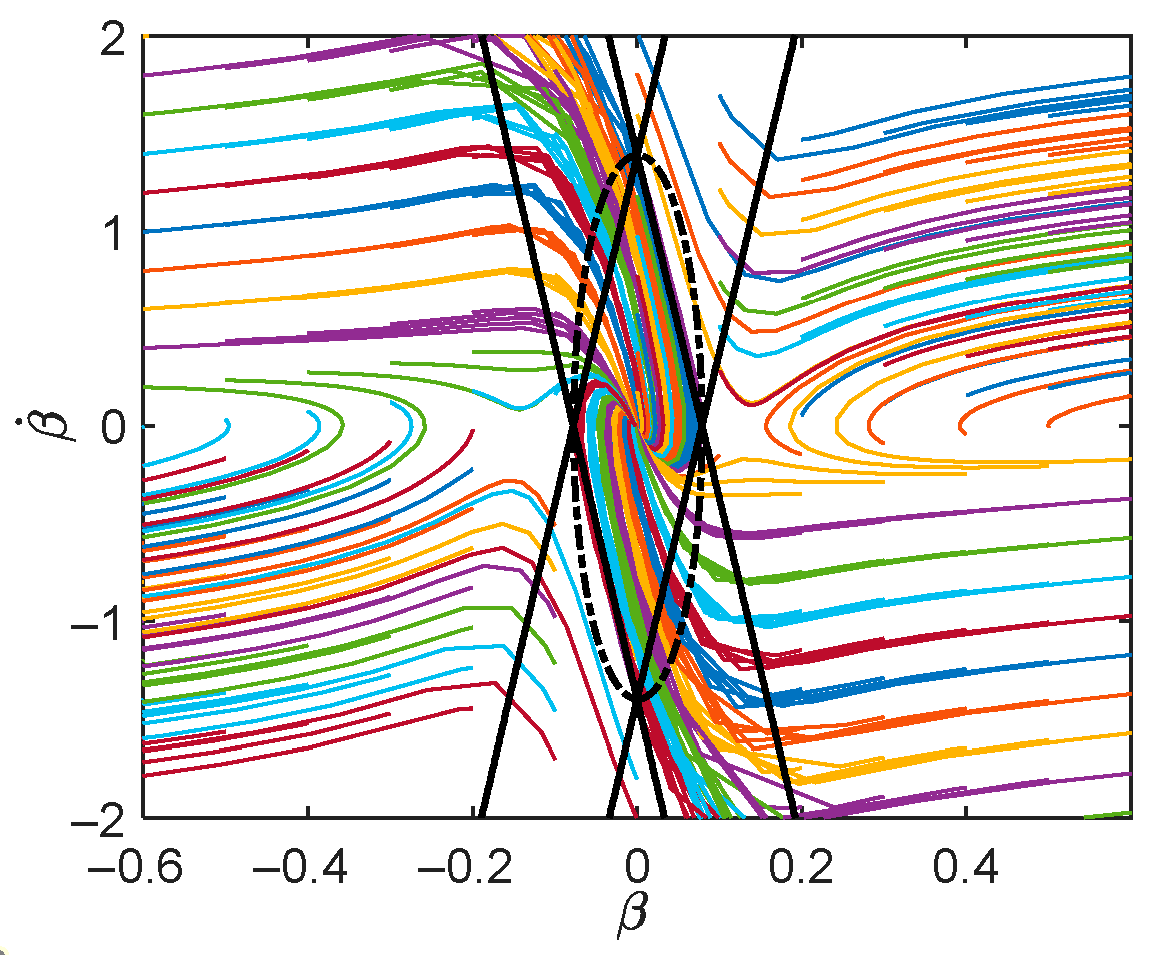

2.3. Vehicle Stability Judgment Based on Extenics Control Theory

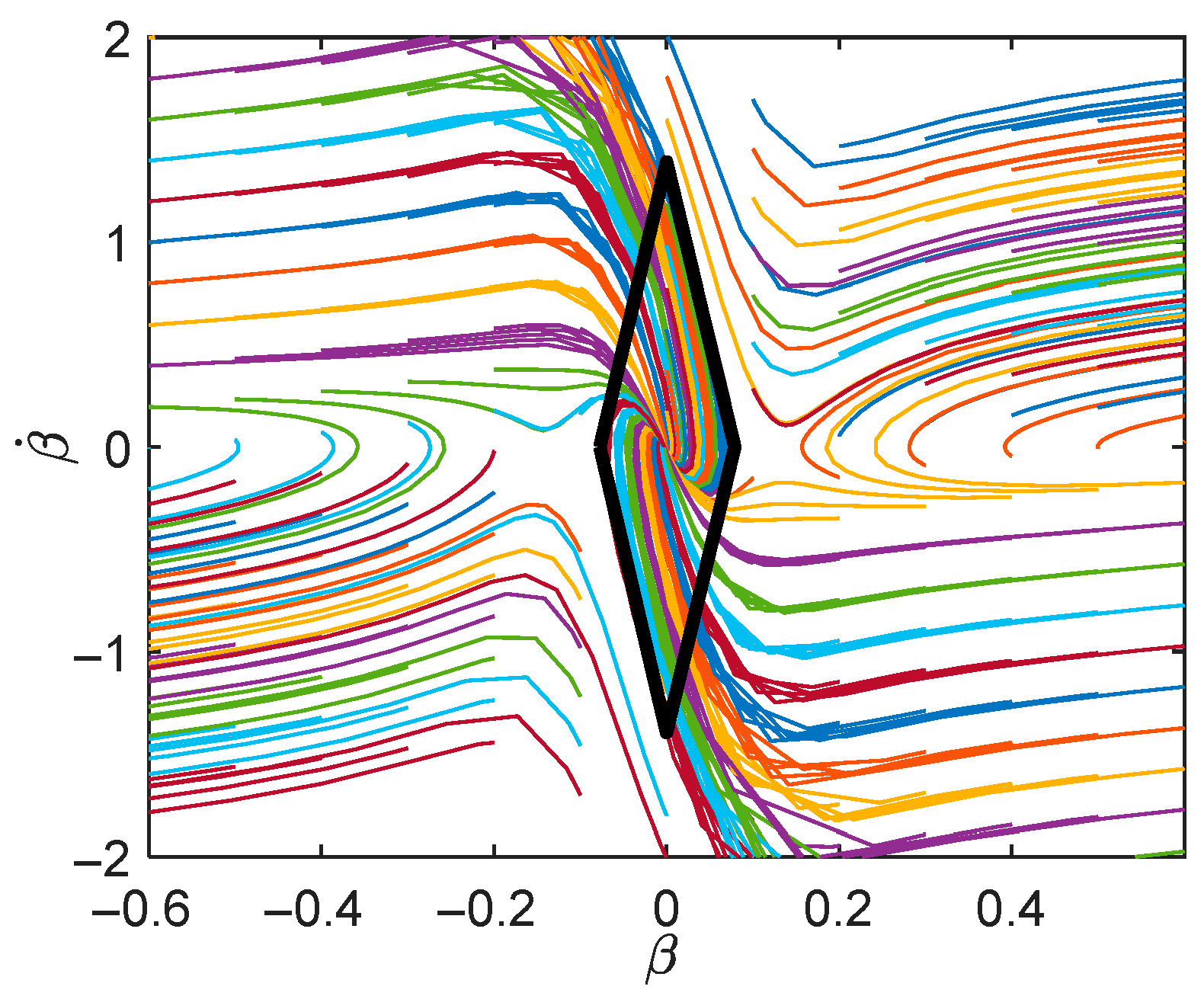

2.3.1. Determination of the Linear Boundary Parameters for the Phase Plane Stability Region

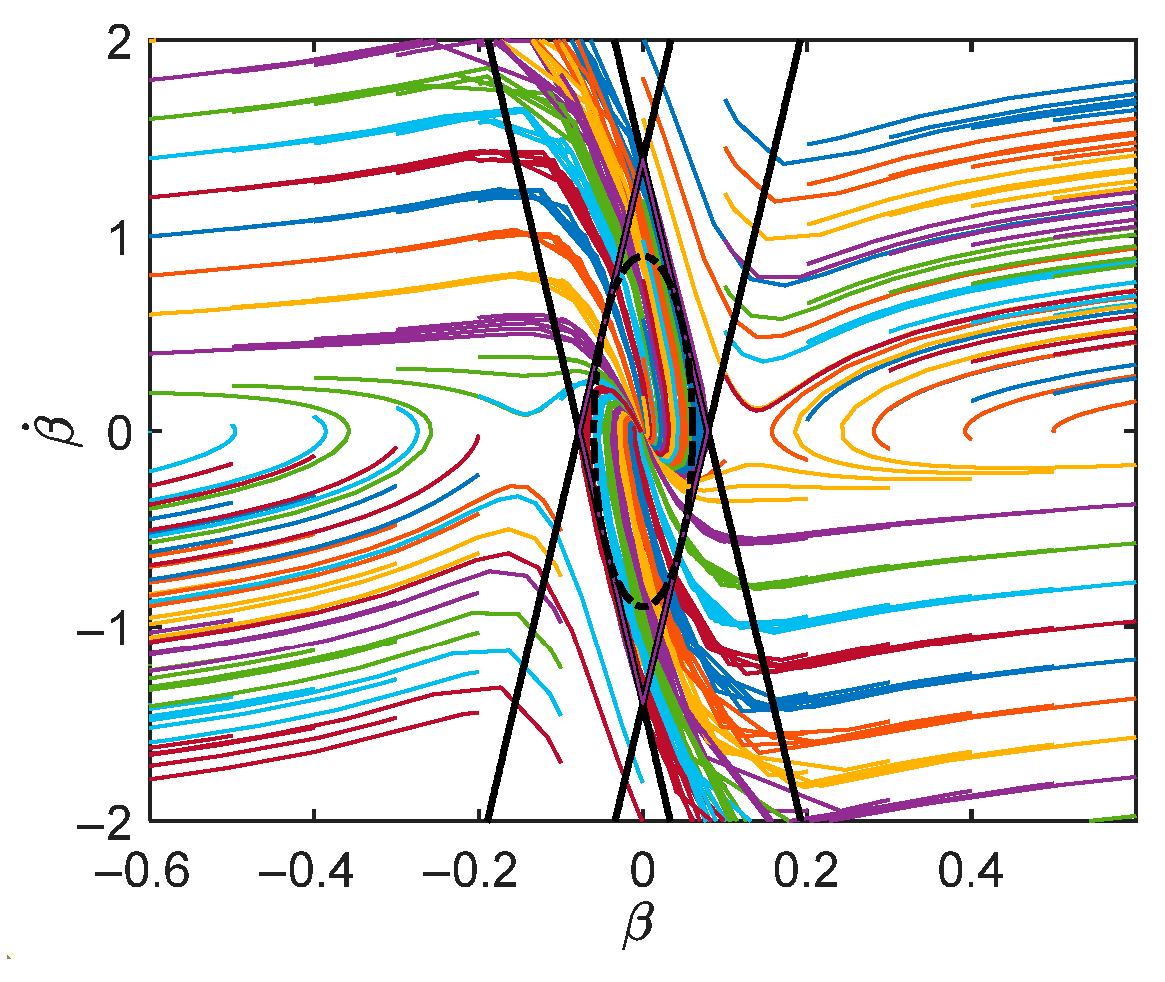

2.3.2. Acquisition of Stability Region Boundary Based on Extenics Control Theory

- (1)

- Determination of the classical domain boundary

- (2)

- Acquisition of extension domain boundaries

- (3)

- Acquisition of extension sets

2.4. Extenics Coordinated Torque Distribution Control Method Based on Energy Efficiency Optimization and Stability

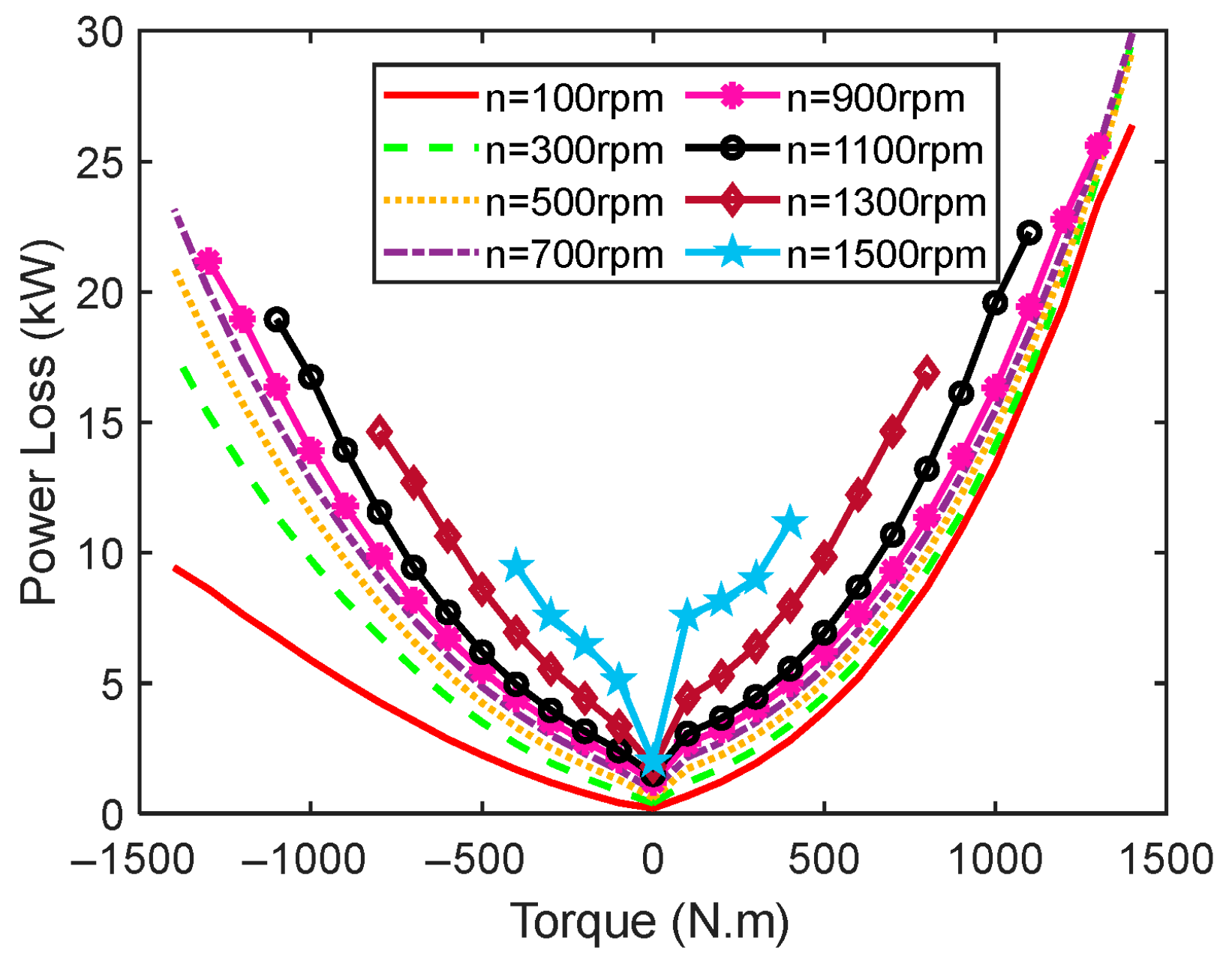

2.4.1. Objective Function and Constraints Based on Energy-Optimal Distribution

2.4.2. Objective Function and Constraints Based on Stability-Oriented Distribution

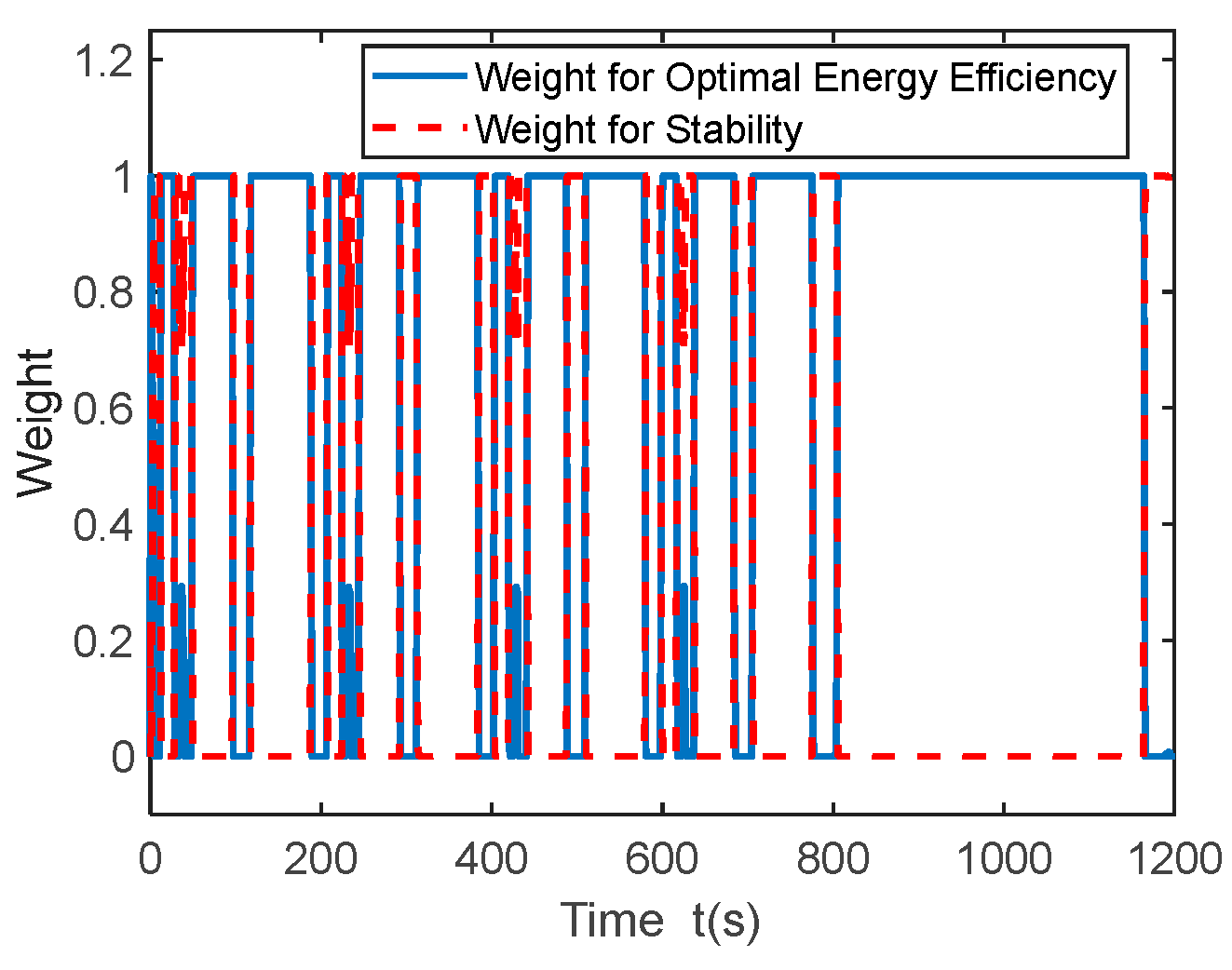

2.4.3. Determination of Weighting Coefficients

- (1)

- Computation of the correlation function

- (2)

- Measurement mode partition and weighting coefficients

2.4.4. Objective Function and Constraints for Extenics Coordinated Control

3. Results and Discussion

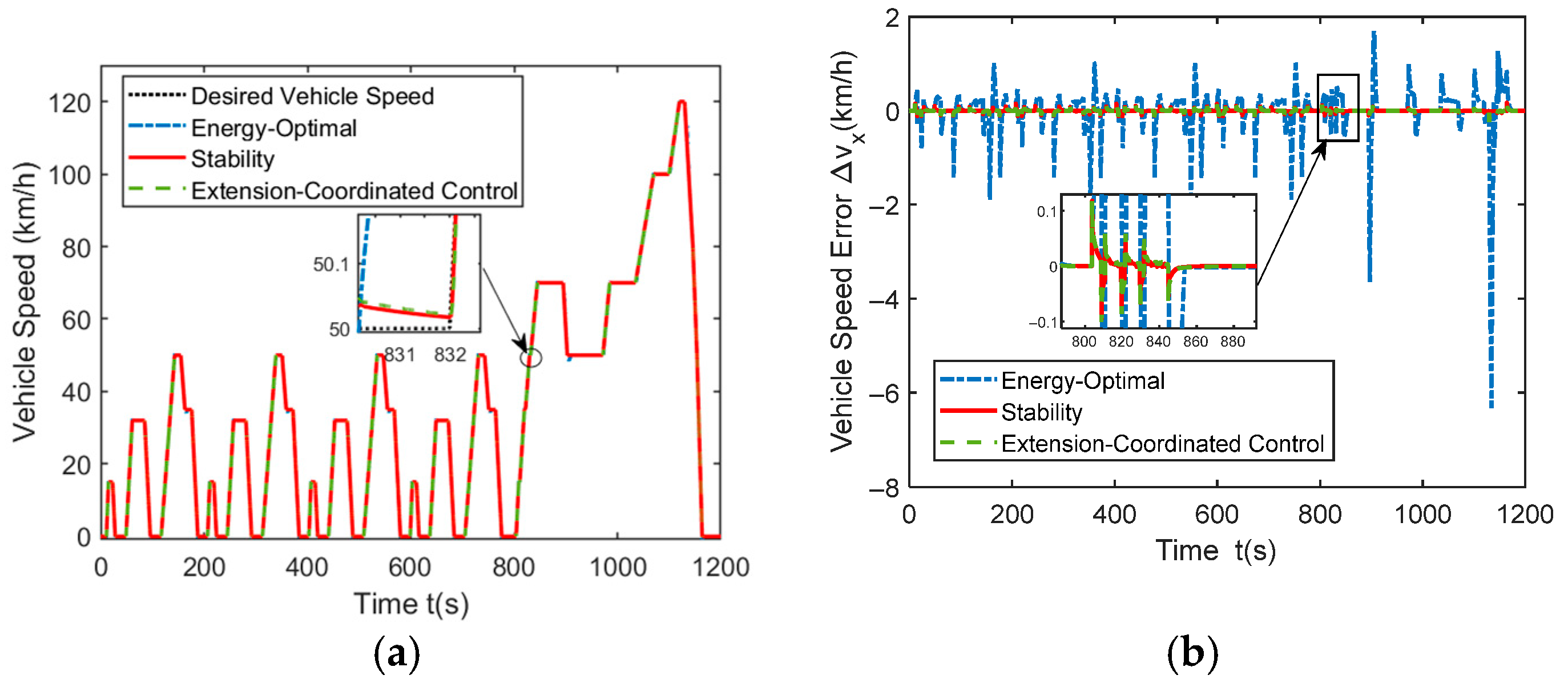

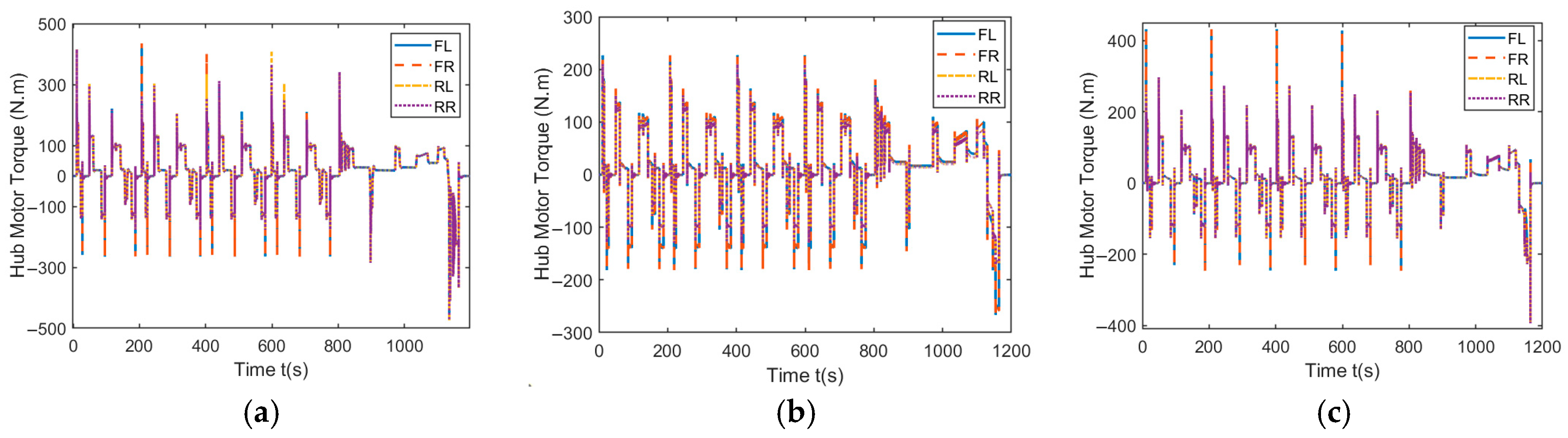

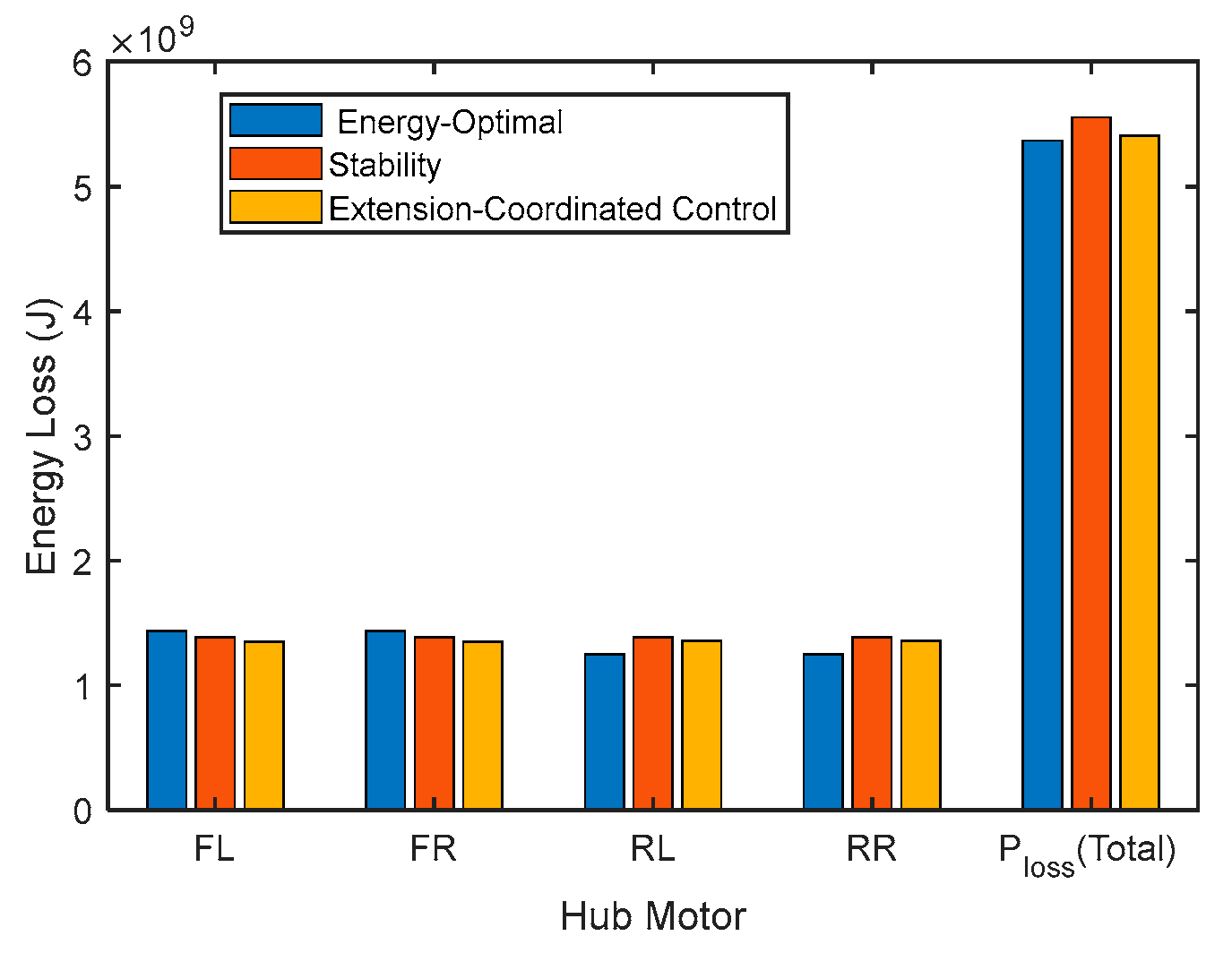

3.1. NEDC Urban Driving Cycle

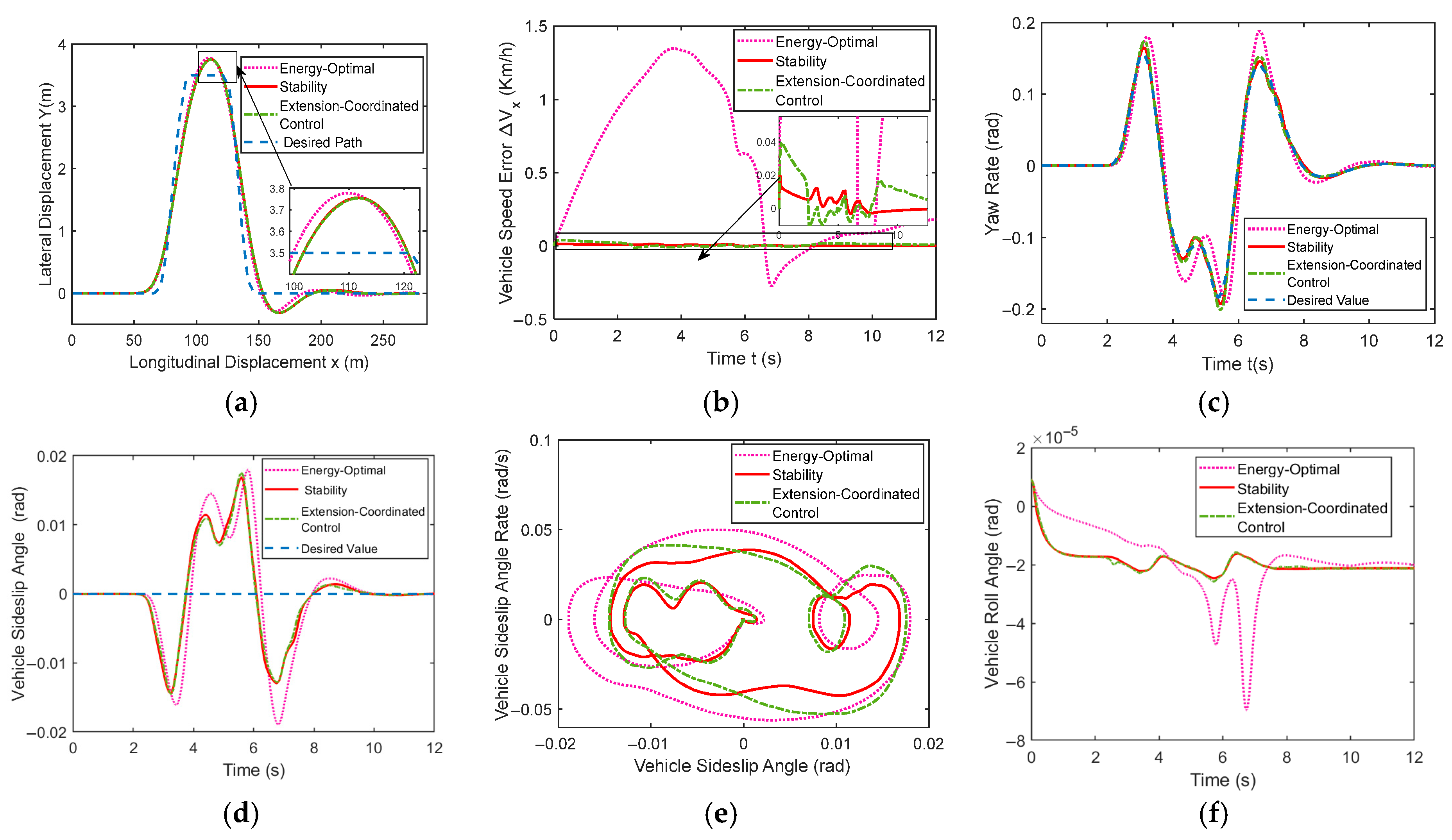

3.2. Double-Lane-Change Maneuver Driving Conditions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, Y.; Zhou, T. Vehicle stability control based on steering angle compensation and torque distribution. Mach. Des. Manuf. Eng. 2020, 49, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Ge, P.; Sun, D. Torque distribution algorithm for stability control of electric vehicle driven by four in wheel motors under emergency conditions. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 104737–104748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, S.; Li, Z.; Guo, L. An energy conservation strategy based on drive mode switching for multi-axle in-wheel motor driven vehicle. Energy Proc. 2019, 158, 2580–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, M.; Chen, G.; Zhang, B.; Huang, Y. A hierarchical energy efficiency optimization control strategy for distributed drive electric vehicles. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. 2019, 233, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Sun, T.; Wang, J. Electronic stability control based on motor driving and braking torque distribution for a four in-wheel motor drive electric vehicle. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2016, 65, 4726–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wang, J.; Guan, C.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Z. Wheel torque distribution control strategy for electric vehicles dynamic performance with an electric torque vectoring drive axle. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 1692–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Huang, H.; Liu, S.; Liu, R.; Liang, C. Coordinated control of stability and anti-slip torque distribution for distributed electric vehicles under extreme operating conditions. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yan, C.; Zhao, L.; Ling, X.; Xie, Y. Torque distribution in distributed drive electric vehicles under steering conditions. China J. Highw. Transp. 2020, 33, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Asiabar, A.; Kazemi, R. A direct yaw moment controller for a four in-wheel motor drive electric vehicle using adaptive sliding mode control. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part K J. Multi-Body Dyn. 2019, 233, 549–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Hong, C.; Zhao, H.; Yuan, L. MPC-based yaw stability control in in-wheel-motored EV via active front steering and motor torque distribution. Mechatronics 2016, 38, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Fan, Y. Hierarchical direct yaw-moment control system design for in-wheel motor driven electric vehicle. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2018, 19, 695–703. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Wang, Z.; Chen, C. Torque vectoring control system for distributed drive electric bus under complicated driving conditions. Assem. Autom. 2022, 42, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Ye, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L. Torque distribution and stability control of distributed drive electric vehicles considering torque loss and wheel slip. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Wu, X.; Wu, C.; Wang, J.; Shu, X. Rule-based torque vectoring distribution strategy combined with slip ratio control to improve the handling stability of distributed drive electric vehicles. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. 2025, 239, 1311–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzo, B.; Filippis, G.; Dizqah, A.; Sorniotti, A.; Gruber, P.; Fallah, S.; Nijs, W. Torque distribution strategies for energy-efficient electric vehicles with multiple drivetrains. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 2017, 139, 121004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H. Torque Allocation Control of Four-Wheel Drive EVs Considering Energy Efficiency Optimization. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, B.; Deng, W.; Chen, H. An energy-efficient torque distribution strategy for in-wheel-motored EVs based on model predictive control. Int. J. Veh. Des. 2020, 82, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Kuang, C.; Chen, P. Economical optimal torque distribution control for distributed four-wheel-drive electric buses. Automob. Technol. 2022, 1, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Adeleke, O.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, W.; Xu, X.; Cui, X. Torque distribution based on dynamic programming algorithm for four in-wheel motor drive electric vehicle considering energy efficiency optimization. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Tao, J.; Xiao, F.; Niu, X.; Fu, C. An optimal torque distribution control strategy for four-wheel independent drive electric vehicles considering energy economy. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 141825–141837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Hu, M.; Wang, D.; Qiao, S.; Guo, C.; Fu, C.; Zhou, A. All-wheel-drive torque distribution strategy for electric vehicle optimal efficiency considering tire slip. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 25245–25257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, L. Research on TVD control of cornering energy consumption for distributed drive electric vehicles based on PMP. Energies 2022, 15, 2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, J.; Yue, M.; Qi, H.; Fang, C. Coordinated control of path tracking and energy optimization for in-wheel motor drive electric buses with velocity estimation. Eur. J. Control 2022, 65, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, N.; Luo, T.; Pan, B.; Li, S.; Cui, X. Energy-efficient torque allocation strategy for autonomous distributed drive electric vehicle. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 8275–8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Zhu, S.; Liu, D.; Xiang, Z.; Fu, H.; Chen, H. Research on the torque control strategy of a distributed 4WD electric vehicle based on economy and stability control. Electronics 2022, 11, 3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Zhao, X. Hierarchical torque vectoring control strategy of distributed driving electric vehicles considering stability and economy. Sensors 2025, 25, 3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, Y. Lane changing enabled eco-driving control for plug-in hybrid electric vehicle under consecutive signalized intersection conditions. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2026, 5, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacejka, H.B. Tyre and Vehicle Dynamics, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, M.; Mallawi, F.; Baleanu, D.; Alshomrani, A. A new fractional study on the chaotic vibration and state-feedback control of a nonlinear suspension system. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 132, 109530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Prasad, A. Fractional delayed feedback for semi-active suspension control of nonlinear jumping quarter car model. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 199, 116973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, H.; Salarieh, H.; Alasty, A.; Meghdari, A. On the control of chaos via fractional delayed feedback method. Comput. Math. Appl. 2011, 62, 1482–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, X.; Tan, D.; Lin, S.; Sun, X.; Xie, Y. Study on the grey predictive extension control of yaw stability of electric vehicle based on the minimum energy consumption. J. Mech. Eng. 2019, 55, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Cong, G.; Xie, Y. Research on steering-by-wire control strategy based on extension sliding mode control. J. Mech. Eng. 2019, 55, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Xia, Q. Automobile Theory; China Machine Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzikomis, C.; Zanchetta, M.; Gruber, P.; Sorniotti, A.; Modic, B.; Motaln, T.; Blagotinsek, L.; Gotovac, G. An energy-efficient torque-vectoring algorithm for electric vehicles with multiple motors. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 128, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Notation | Physical Quantity |

|---|---|

| Y | Output variable, representing the tire longitudinal force Fx, lateral force Fy, or aligning moment Mz |

| X | Input variable, representing the wheel slip angle or longitudinal slip ratio |

| B | Stiffness factor, determining the slope at the origin |

| C | Shape factor, influencing the form of the curve and defining the effective range of the sine function |

| D | Peak factor, controlling the maximum value of the curve |

| E | Curvature factor, adjusting the curvature near the peak and influencing the horizontal position of the maximum value |

| SV | Vertical shift in the curve relative to the origin |

| SH | Horizontal shift in the curve relative to the origin |

| Parameter | Abscissa /(Rad) | Ordinate /(Rad/s) |

|---|---|---|

| Left endpoint | 0 | |

| Right endpoint | 0 | |

| Top vertex | 0 | |

| Bottom vertex | 0 | |

| Stable point | 0 | 0 |

| Parameters | Unit | Value | Parameters | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | kg | 1750 | Bf | m | 1.55 |

| Iz | kg·m2 | 2954 | Br | m | 1.55 |

| Lf | m | 1.27 | Rij | m | 0.357 |

| Lr | m | 1.4 | hg | m | 0.54 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Shu, Q.; Zhou, D.; Ti, Y. Extenics Coordinated Torque Distribution Control for Distributed Drive Electric Vehicles Considering Stability and Energy Efficiency. Actuators 2026, 15, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010003

Wang L, Shu Q, Zhou D, Ti Y. Extenics Coordinated Torque Distribution Control for Distributed Drive Electric Vehicles Considering Stability and Energy Efficiency. Actuators. 2026; 15(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Liang, Qiuxia Shu, Dashuang Zhou, and Yan Ti. 2026. "Extenics Coordinated Torque Distribution Control for Distributed Drive Electric Vehicles Considering Stability and Energy Efficiency" Actuators 15, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010003

APA StyleWang, L., Shu, Q., Zhou, D., & Ti, Y. (2026). Extenics Coordinated Torque Distribution Control for Distributed Drive Electric Vehicles Considering Stability and Energy Efficiency. Actuators, 15(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010003