Bionic Design Based on McKibben Muscles and Elbow Flexion and Extension Assist Device

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Review of McKibben Pneumatic Muscle Research

2.1. Development History of McKibben Pneumatic Muscles

2.2. Progress of McKibben Pneumatic Muscles

3. System Design and Concept

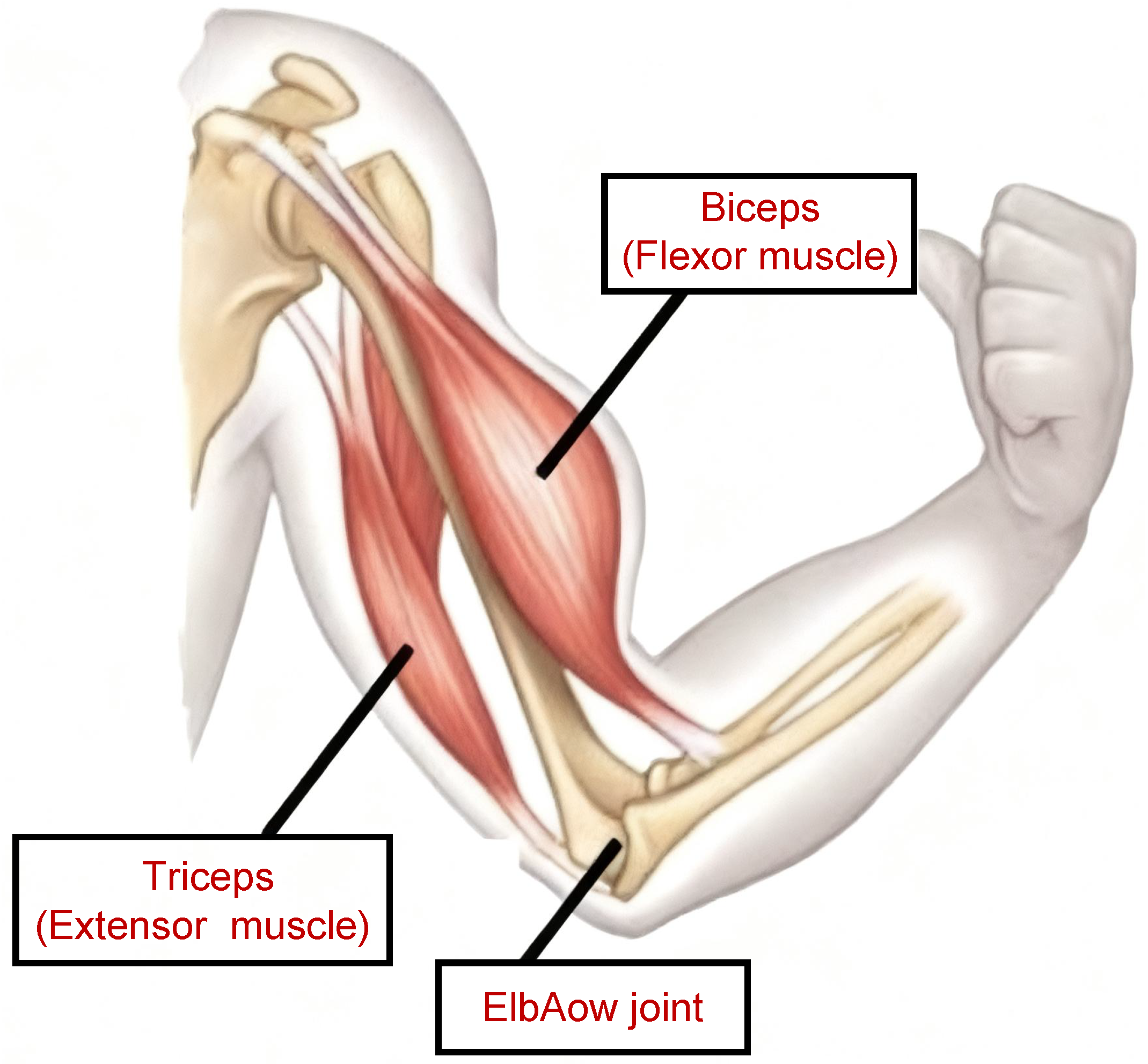

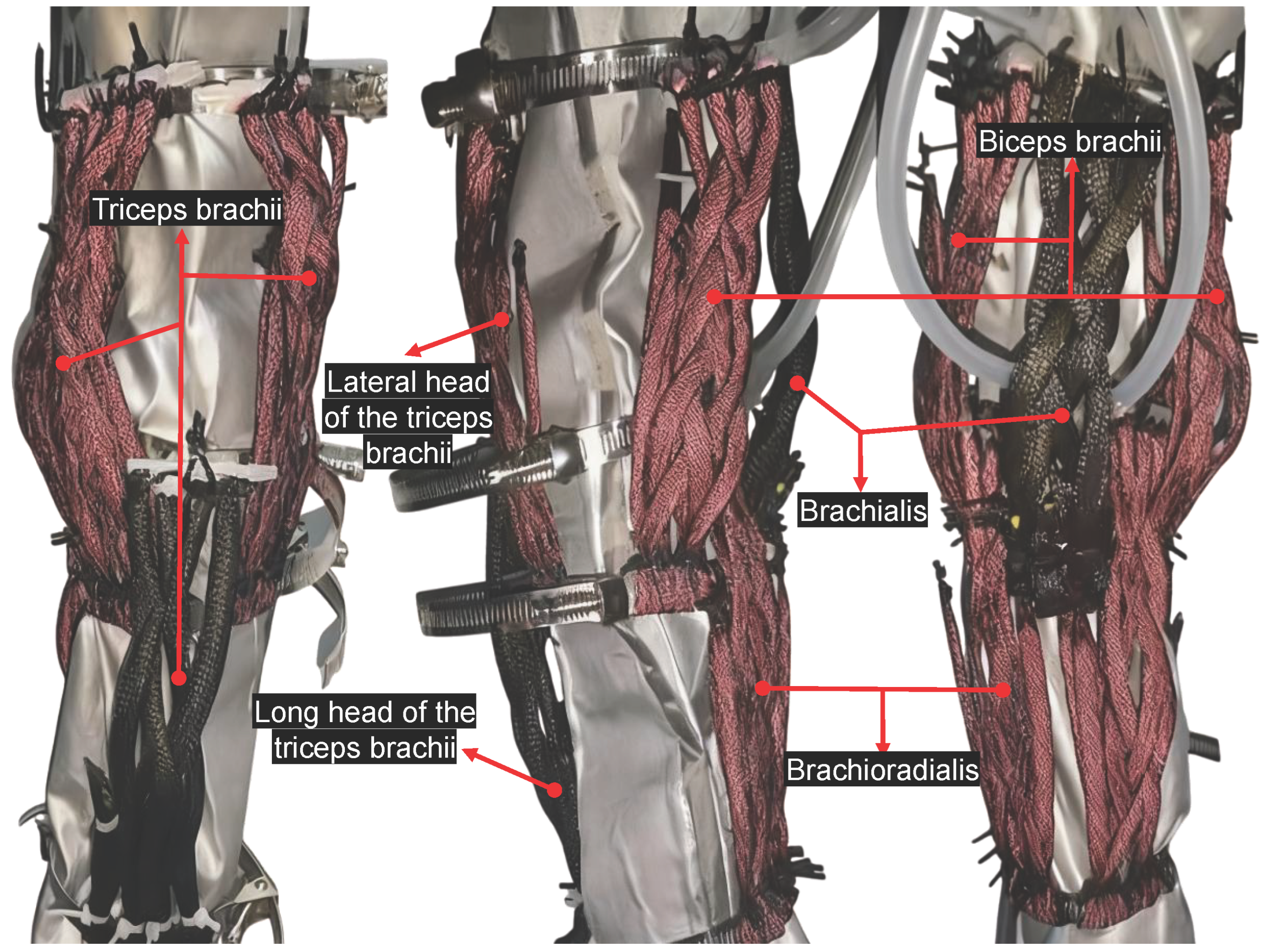

3.1. Overall Structural Design Concept

Antagonistic McKibben Tendon Design

3.2. Mathematical Model

3.2.1. Modeling of the McKibben Pneumatic Muscle Actuator

3.2.2. Kinematic Modeling of the Entire Exoskeleton Robot

4. Prototype Fabrication

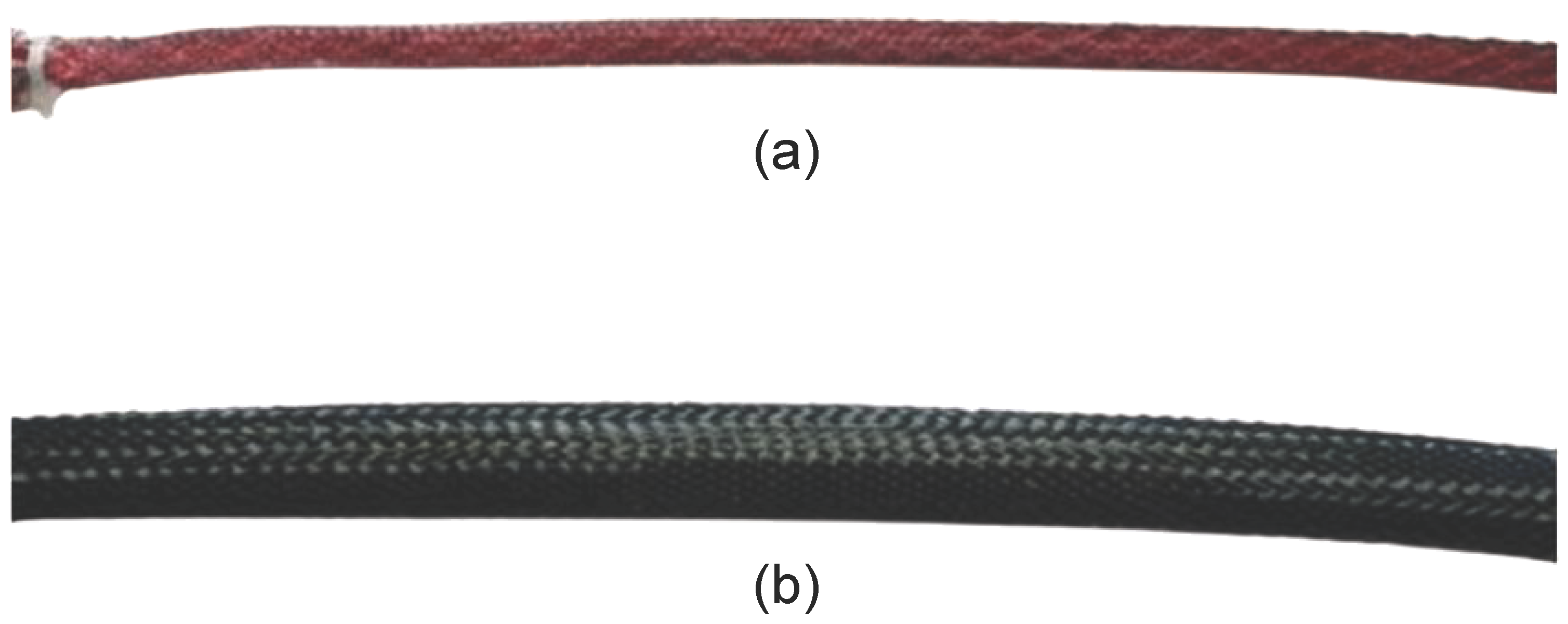

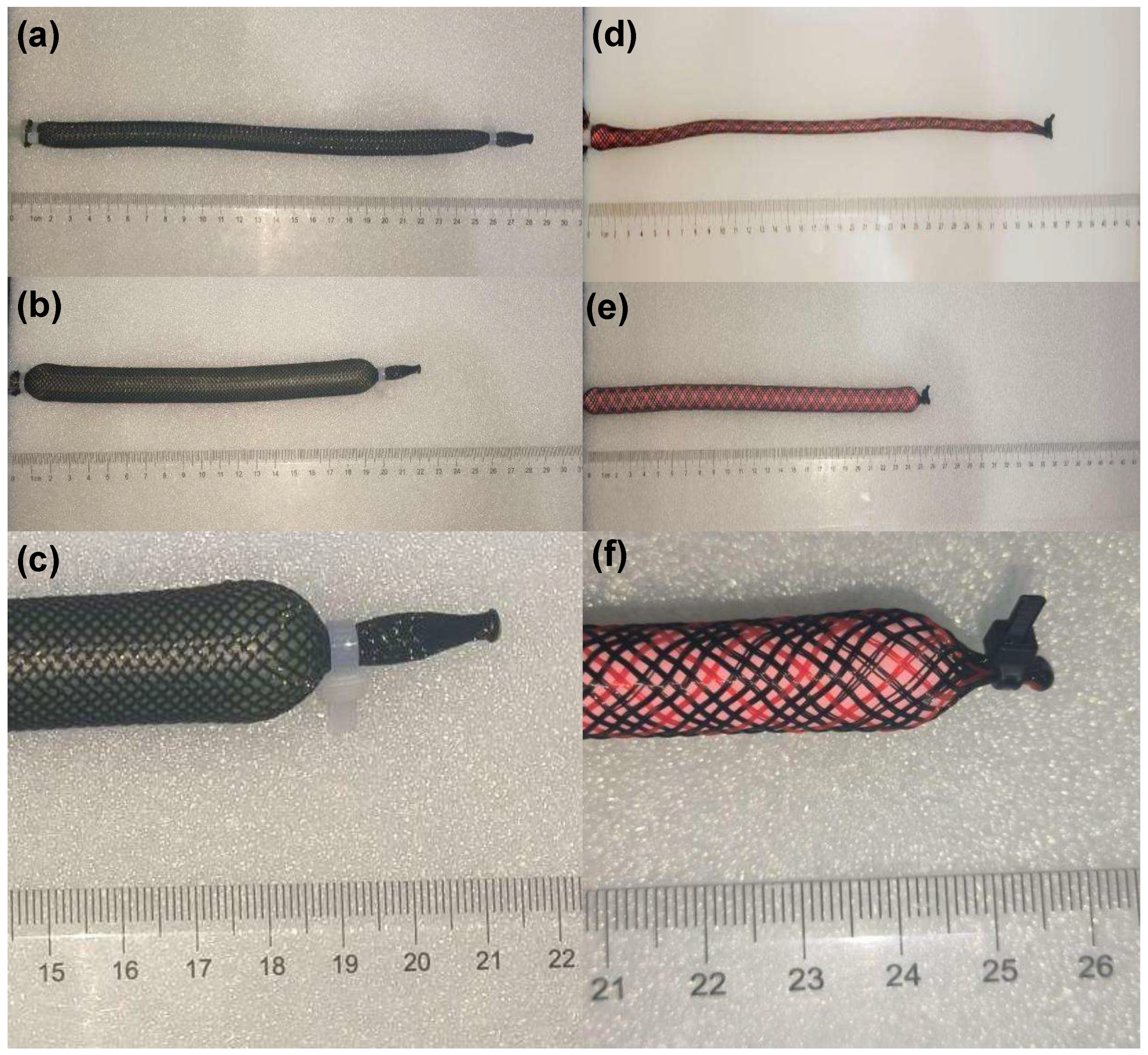

4.1. Design and Fabrication of a Single Pneumatic Muscle

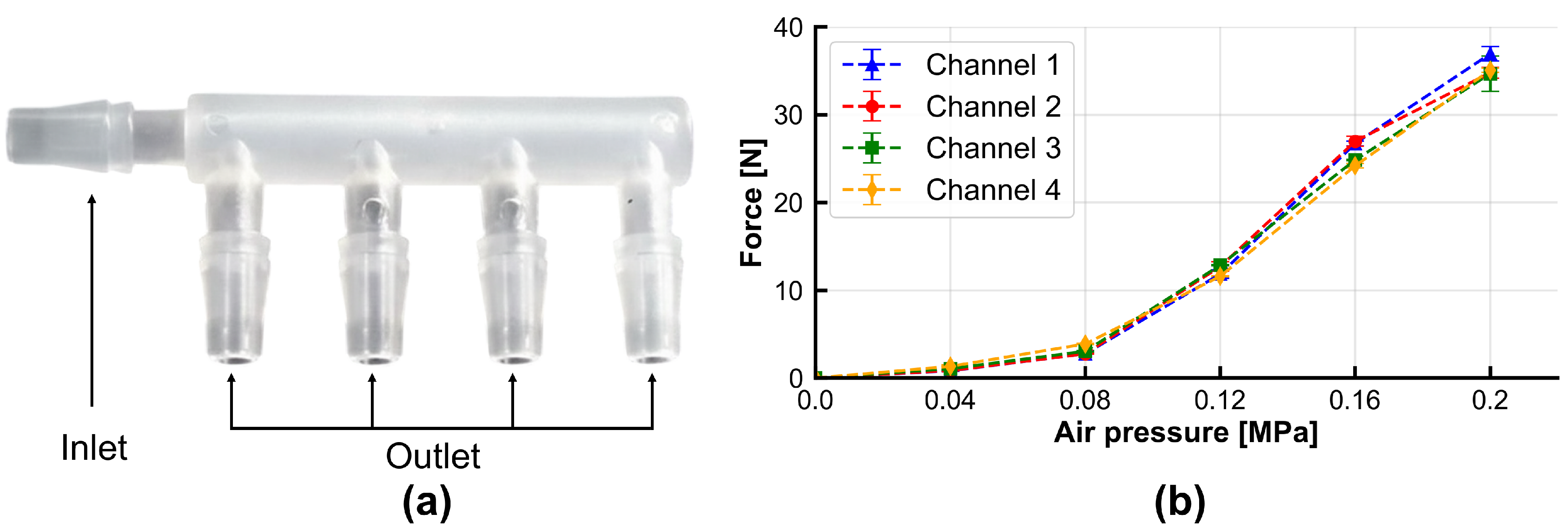

4.1.1. Sealed Connection Design for Pneumatic Muscle

4.1.2. Selection of Constraint Layer and Expanding Bladder Materials

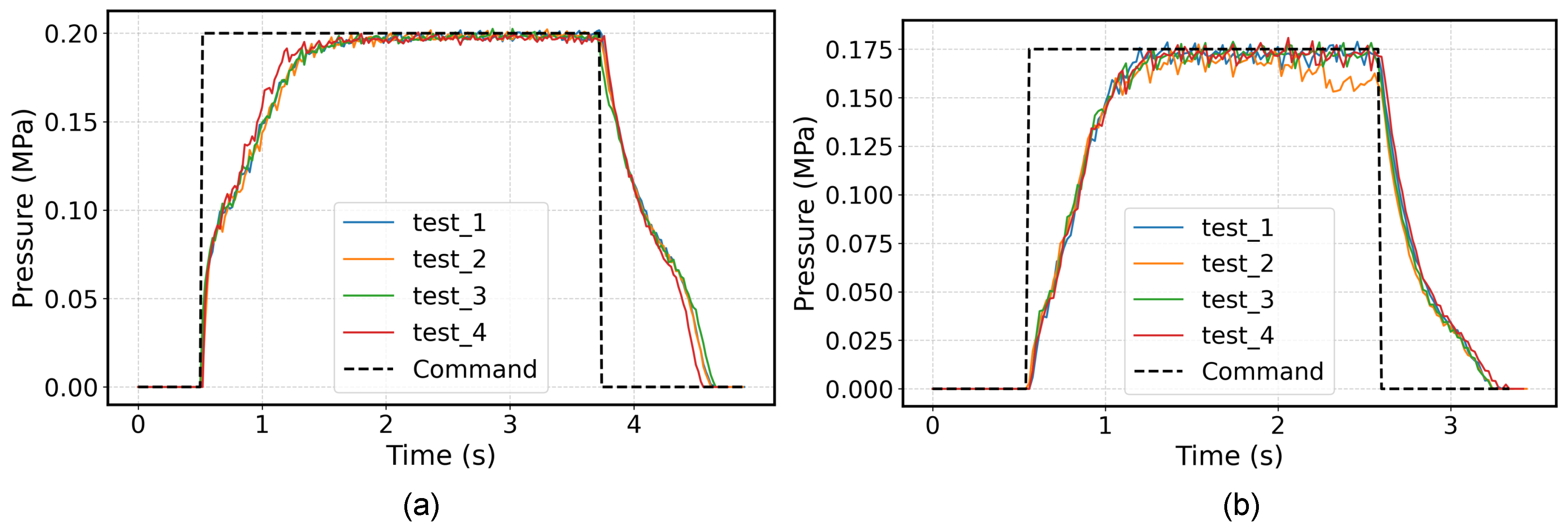

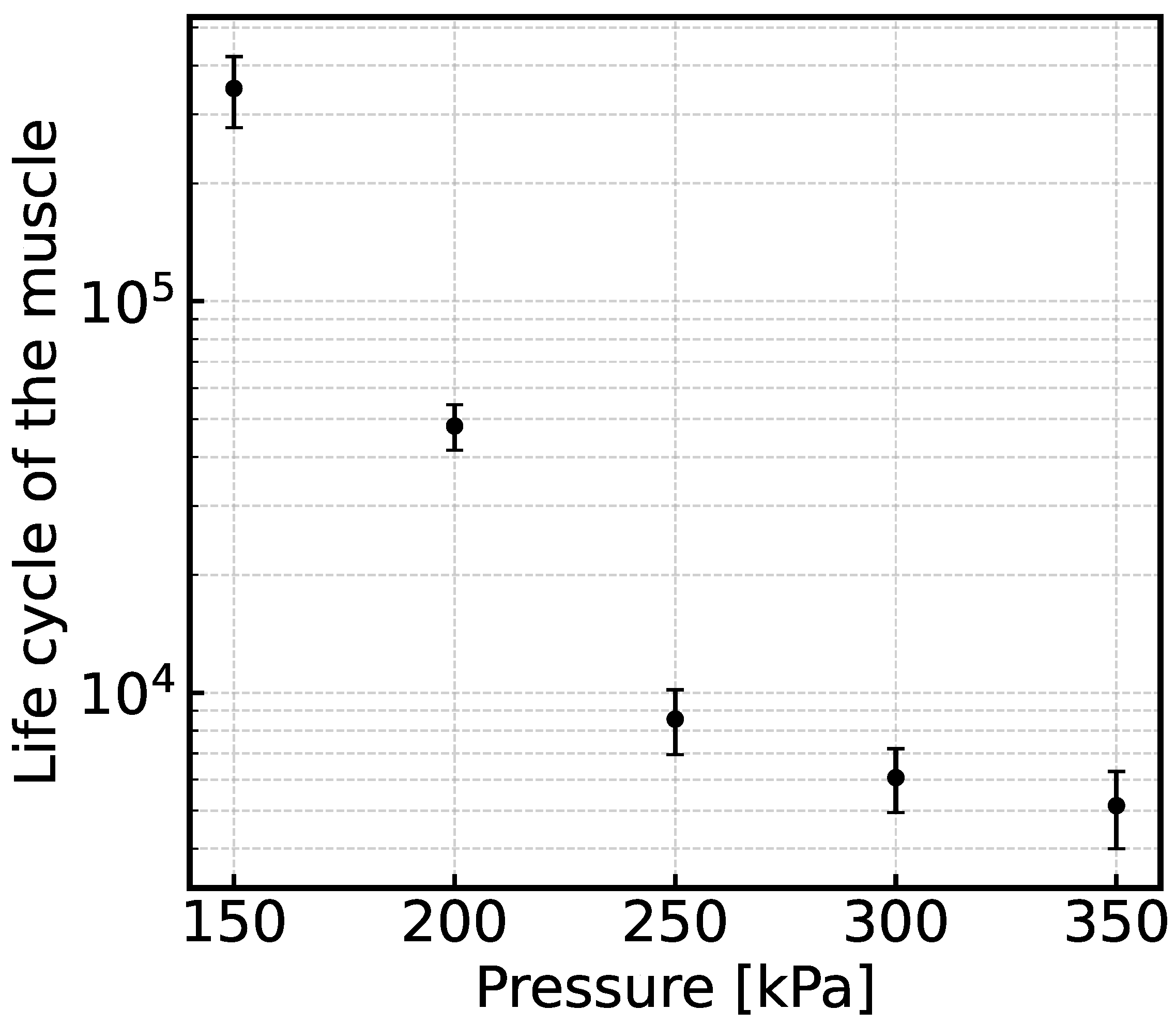

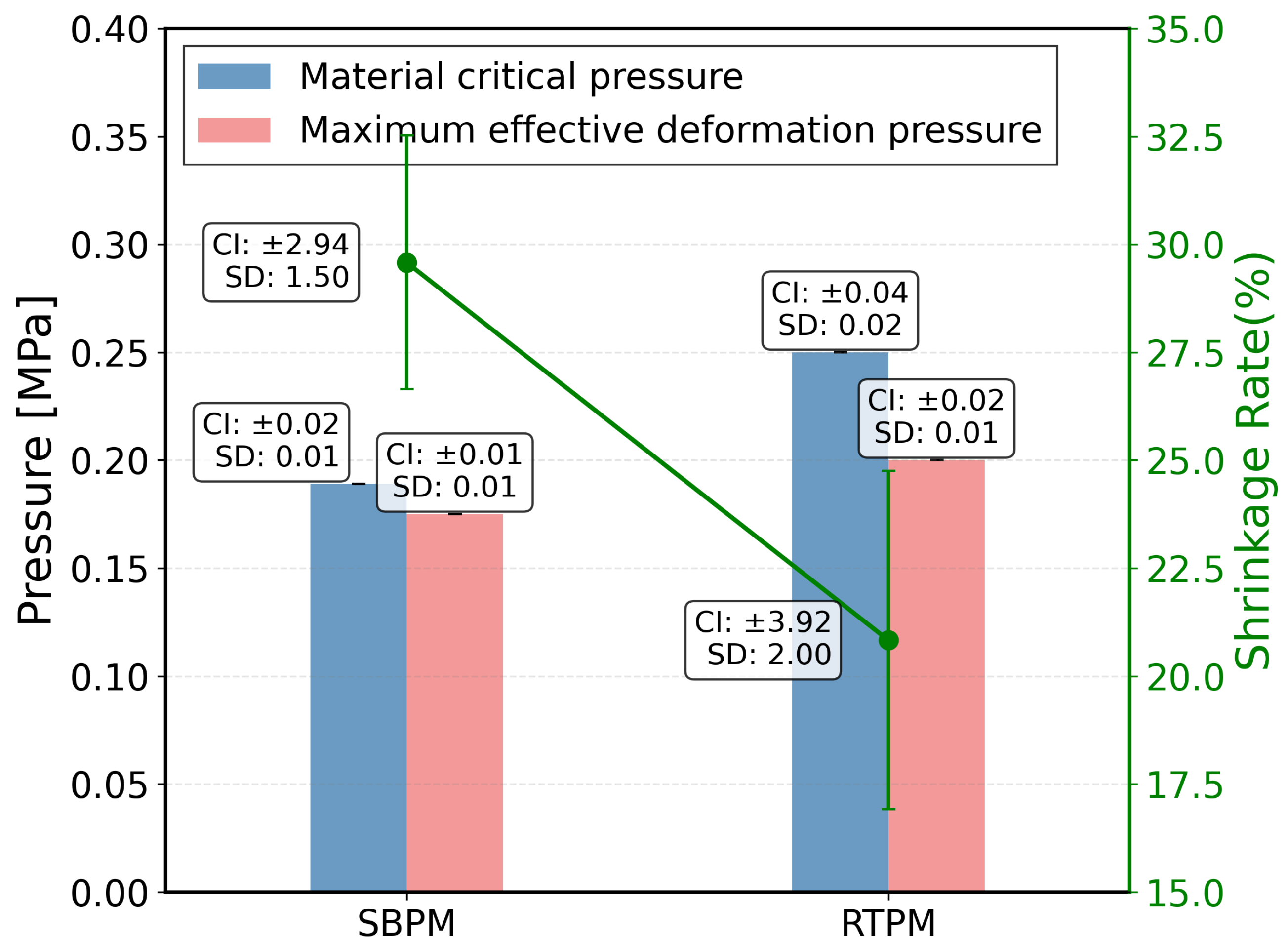

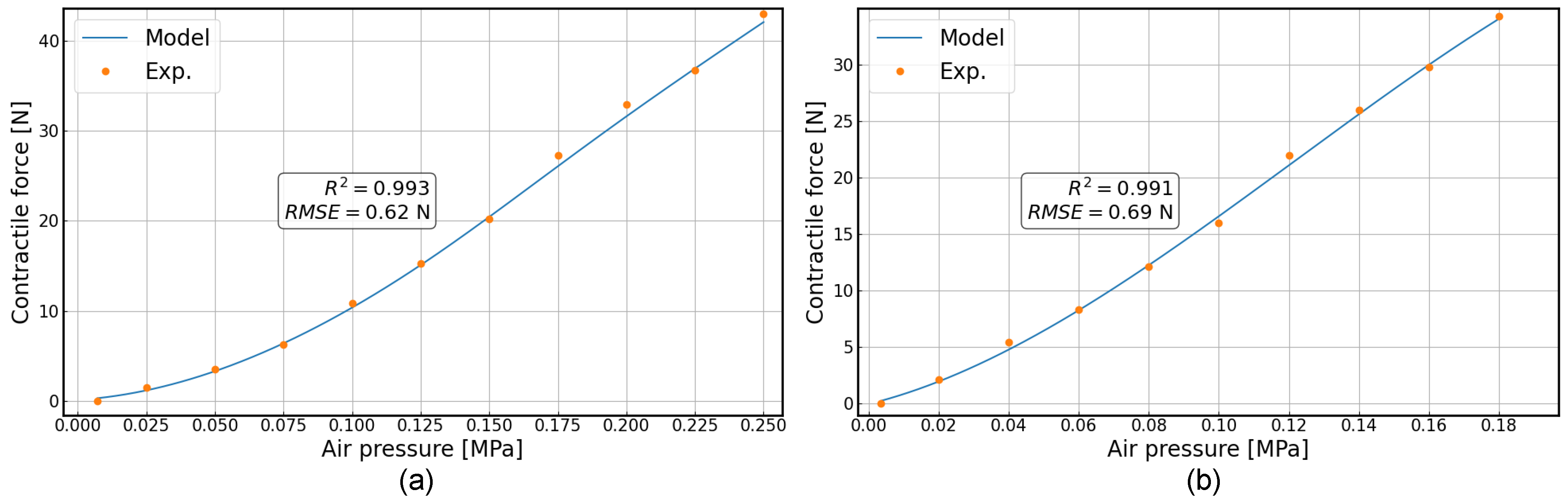

4.1.3. Single Pneumatic Muscle Contraction Experiment

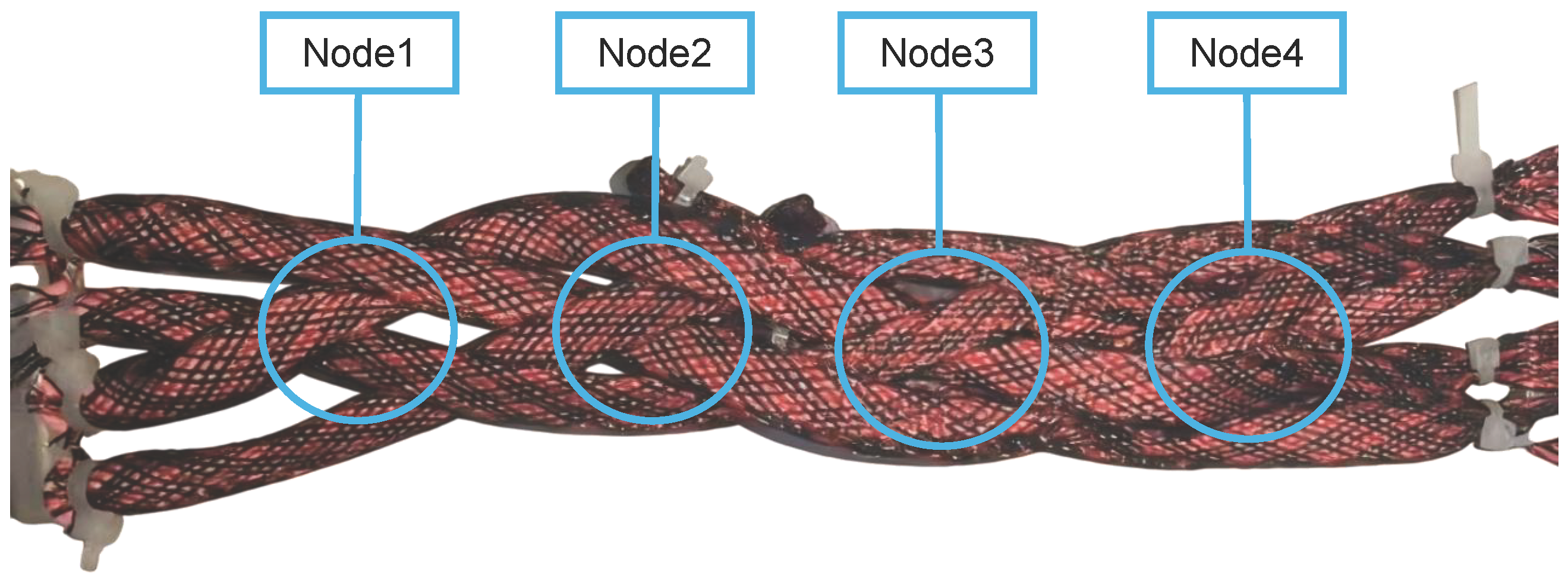

4.2. Design and Fabrication of the McKibben Pneumatic Muscle Fabric Assembly

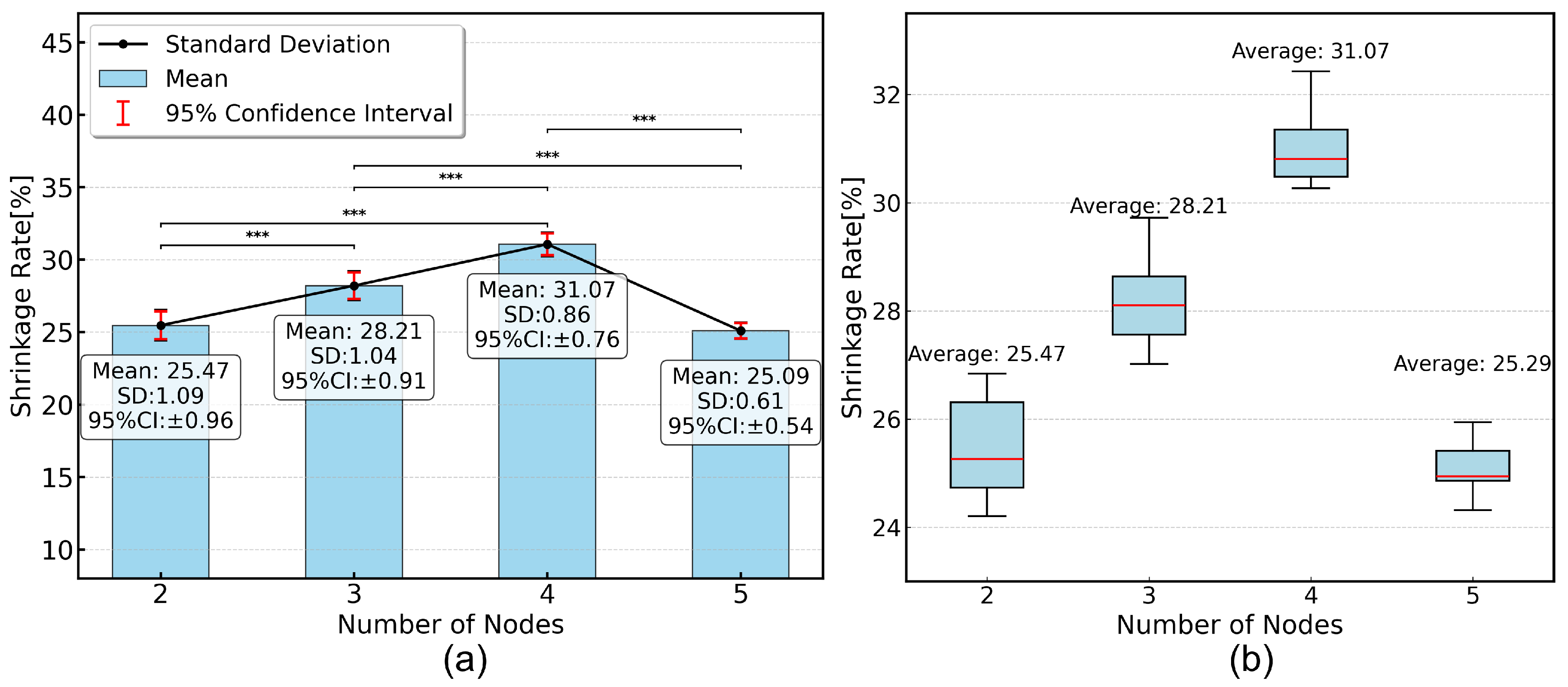

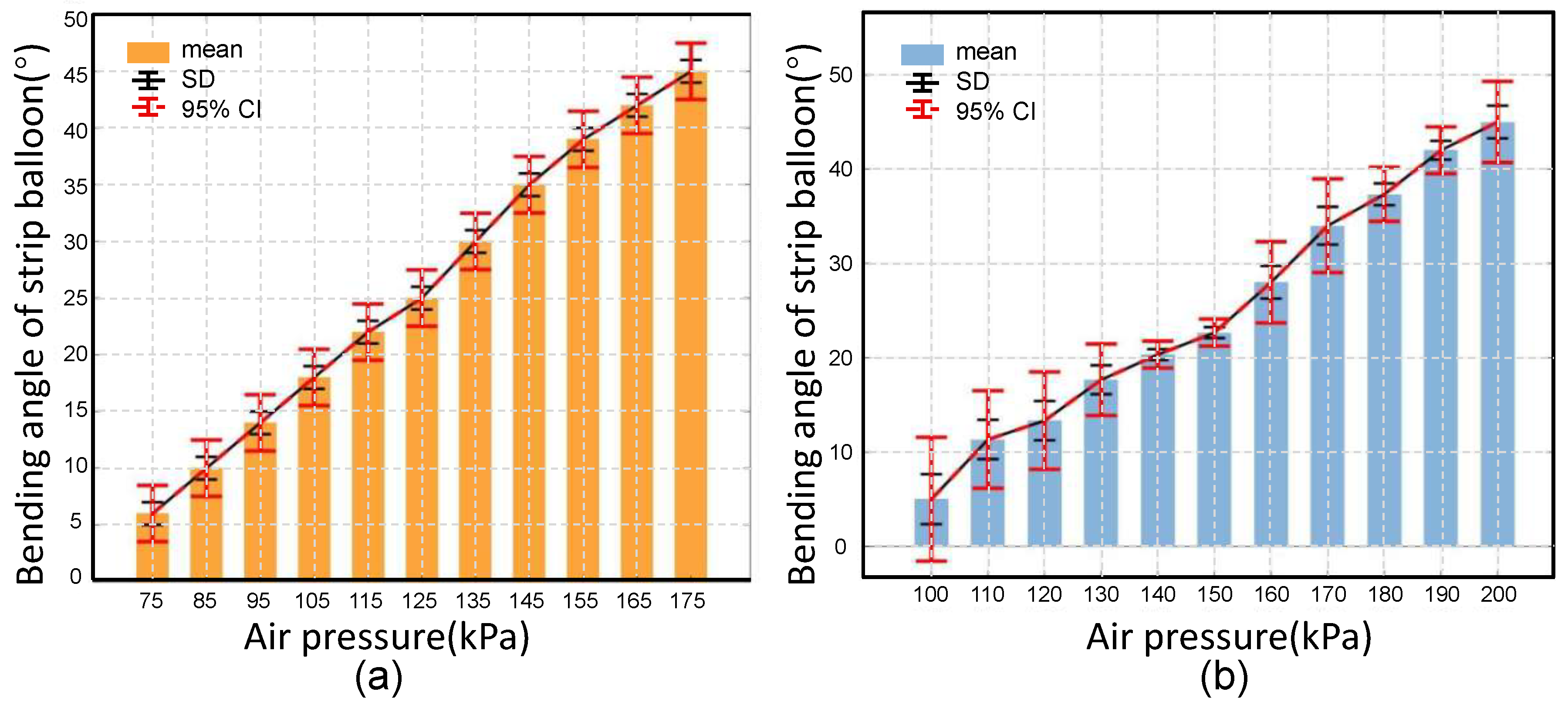

Fabric Group Performance Testing Experiment

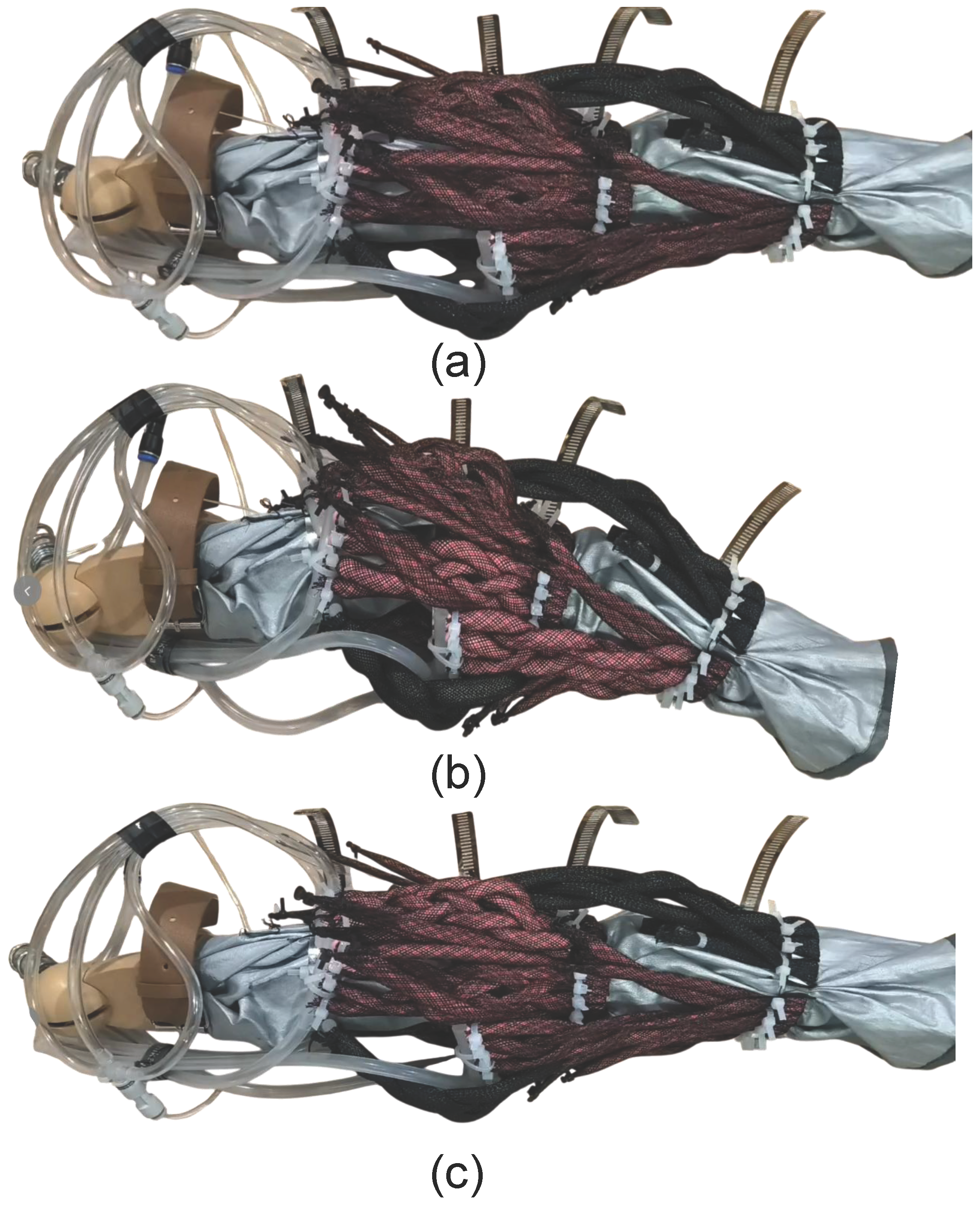

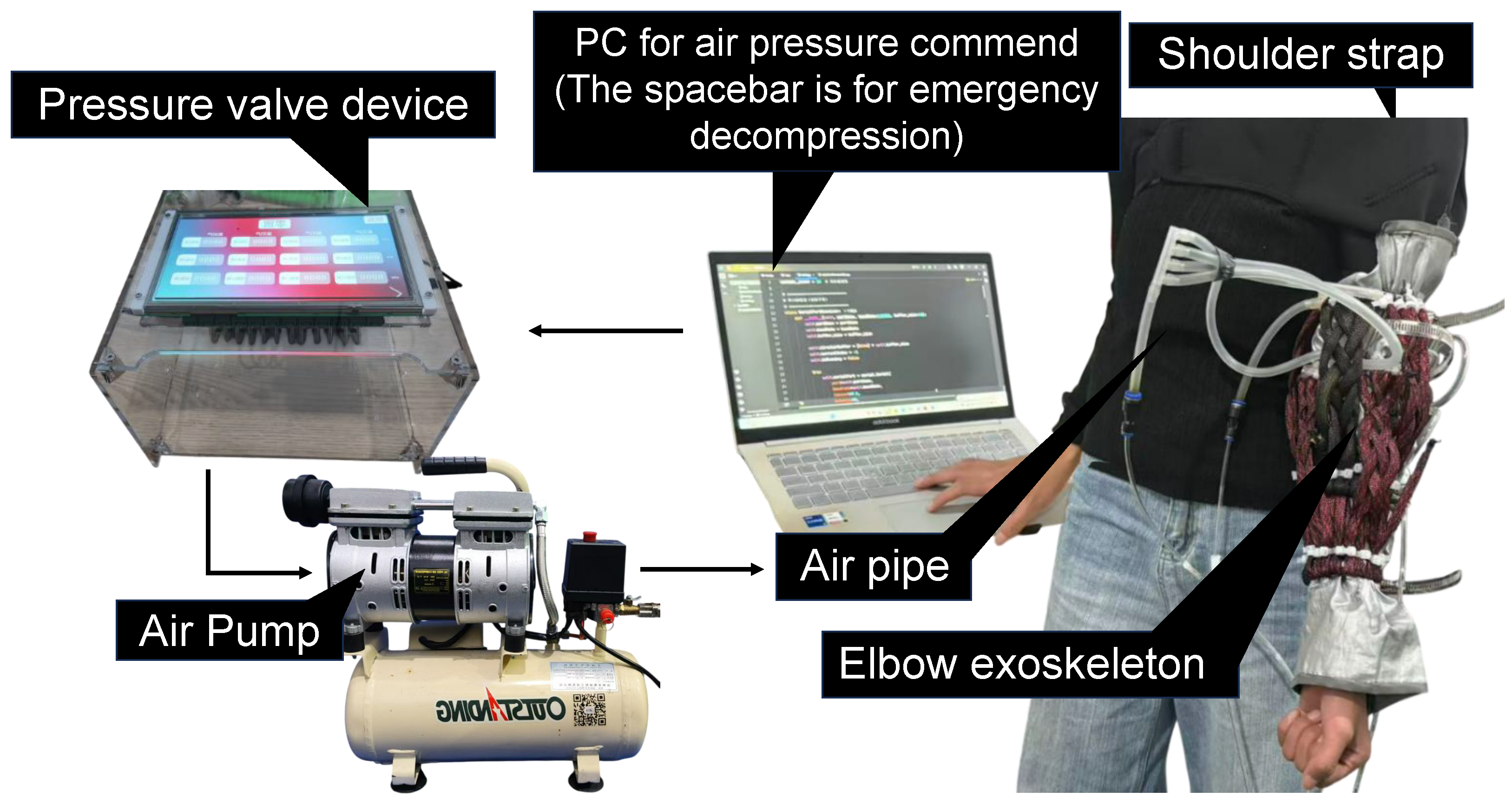

5. Complete System Assembly

6. Physical Experiments

6.1. Model Tests

6.1.1. Experimental Design

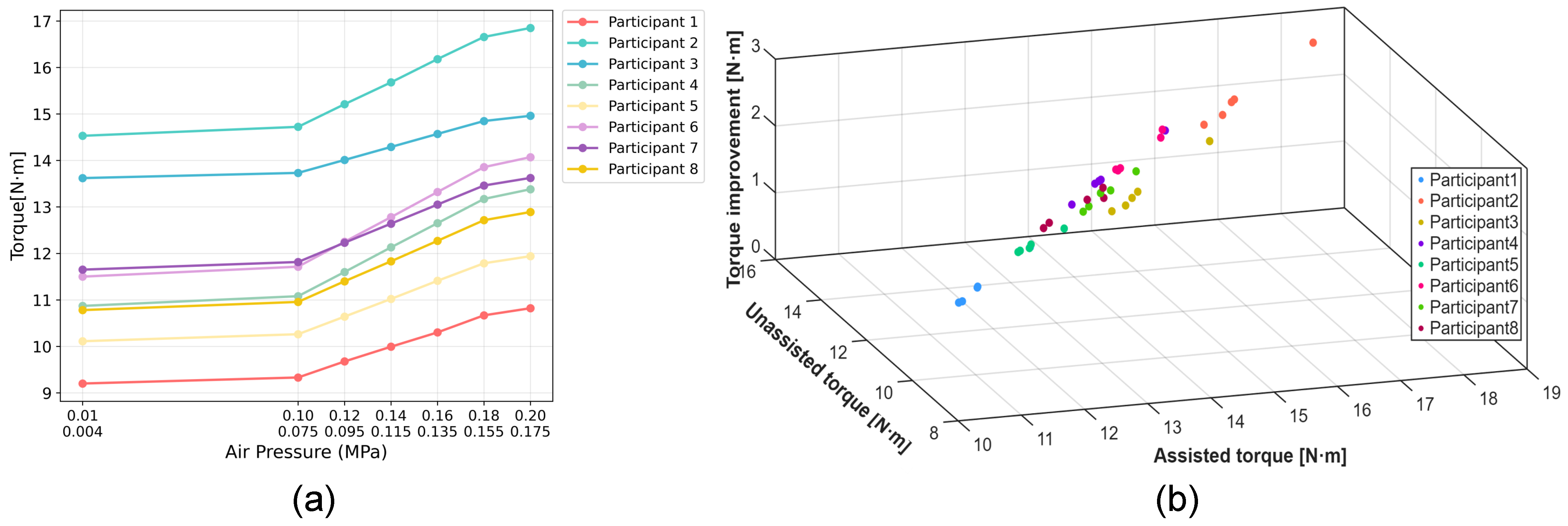

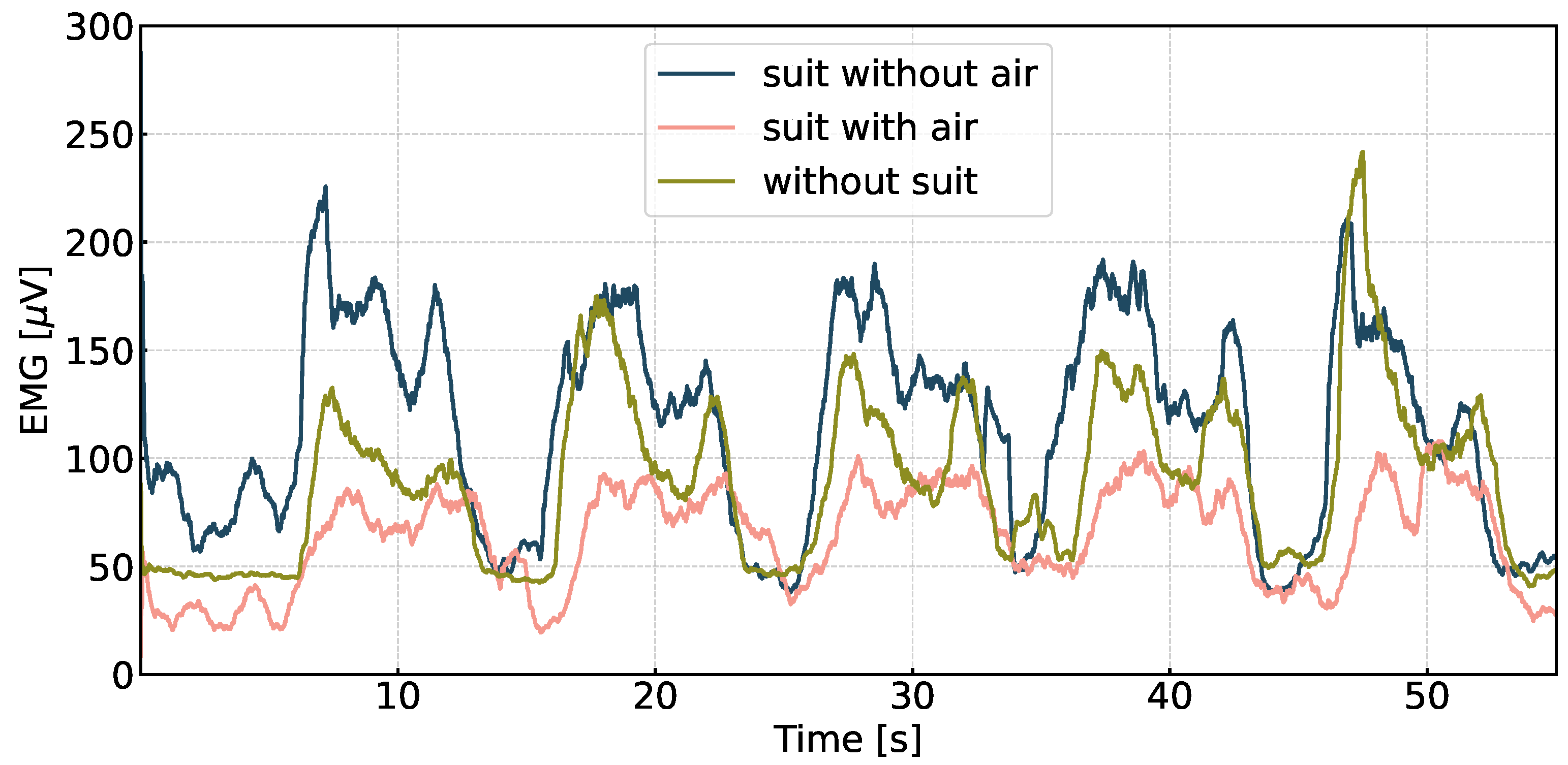

6.1.2. Characterization Results and Discussion

6.2. User Trials

6.2.1. Experimental Design with Human Participants

6.2.2. Functional Performance Results and Discussion

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rocha, C.D.; Carneiro, I.; Torres, M.; Oliveira, H.P.; Pires, E.J.S.; Silva, M.F. Post-stroke upper limb rehabilitation: Clinical practices, compensatory movements, assessment, and trends. Prog. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 7, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wen, T.R.; Yang, L.J.; Sun, X.H.; Lin, P.F.; Liu, S.W. Post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and its correlation with clinical symptoms. Healthc. Rehabil. 2025, 1, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.; Jeong, S.; Herrin, K.R.; Desai, J.P. Hand exoskeleton systems, clinical rehabilitation practices, and future prospects. IEEE Trans. Med. Robot. Bionics 2021, 3, 606–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Suzuki, S.; Nabae, H.; Miyagawa, S.; Suzumori, K.; Maeda, S. Machine learning-enhanced soft robotic system inspired by rectal functions to investigate fecal incontinence. Bio-Des. Manuf. 2025, 8, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Suzuki, S.; Wiranata, A.; Zheng, Y.; Miyagawa, S. Bio-inspired circular soft actuators for simulating defecation process of human rectum. J. Artif. Organs 2025, 28, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Du, S.; Zhong, W.; Xu, Y.; Pu, C.; Páez, L.M.R.; Qian, P. Linear active disturbance rejection motion control of a novel pneumatic actuator with linear-rotary compound motion. Int. J. Hydromechatron. 2024, 7, 382–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Hu, X. Robust active disturbance rejection control for modular fluidic soft actuators. Int. J. Hydromechatron. 2024, 7, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurumaya, S.; Nabae, H.; Endo, G.; Suzumori, K. Design of thin McKibben muscle and multifilament structure. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2017, 261, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, S.; Kurumaya, S.; Nabae, H.; Endo, G.; Suzumori, K. Braiding thin McKibben muscles to enhance their contracting abilities. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 3240–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Koizumi, S.; Nabae, H.; Endo, G.; Suzumori, K.; Sato, N.; Adachi, M.; Takamizawa, F. Fabrication of “18 weave” muscles and their application to soft power support suit for upper limbs using thin mckibben muscle. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 2532–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, G.; Nabae, H.; Suzumori, K. Braided thin mckibben muscles for musculoskeletal robots. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2023, 357, 114381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, R.; Khajehsaeid, H. A mechanical model for McKibben pneumatic artificial muscles based on limiting chain extensibility and 3D application of the network alteration theories. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2020, 202, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-P.; Hannaford, B. Measurement and modeling of McKibben pneumatic artificial muscles. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1996, 12, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, M.G.; Beomonte Zobel, P.; D’Ambrogio, W.; Durante, F.; Raparelli, T. An analytical formula for designing McKibben pneumatic muscles. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 320–337. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.; Hyeon, K.; Jang, S.-Y.; Chung, C.; Hussain, S.; Ahn, S.-Y.; Bok, S.-K.; Kyung, K.-U. Soft wearable robot with shape memory alloy (SMA)-based artificial muscle for assisting with elbow flexion and forearm supination/pronation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 6028–6035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.H.; Sakai, Y.; Funabora, Y.; Yokoe, K.; Aoyama, T.; Doki, S. Funabot-Sleeve: A Wearable Device Employing McKibben Artificial Muscles for Haptic Sensation in the Forearm. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 1944–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Sakai, Y.; Nakagawa, K.; Funabora, Y.; Aoyama, T.; Yokoe, K.; Doki, S. Funabot-Suit: A bio-inspired and McKibben muscle-actuated suit for natural kinesthetic perception. Biomim. Intell. Robot. 2023, 3, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschiersky, M.; Hekman, E.G.; Brouwer, D.M.; Herder, J.L.; Suzumori, K. A compact McKibben muscle based bending actuator for close-to-body application in assistive wearable robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 3042–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; Yu, J. Design and control of the McKibben artificial muscles actuated humanoid manipulator. In Rehabilitation of the Human Bone-Muscle System; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hocking, E.G.; Wereley, N.M. Analysis of nonlinear elastic behavior in miniature pneumatic artificial muscles. Smart Mater. Struct. 2012, 22, 014016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothera, C.S.; Jangid, M.; Sirohi, J.; Wereley, N.M. Experimental characterization and static modeling of McKibben actuators. In Proceedings of the ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Chicago, IL, USA, 5–10 November 2006; pp. 357–367. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, B.T.; Scherzinger, W.M. Trust-region based return mapping algorithm for implicit integration of elastic-plastic constitutive models. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2017, 112, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, B.K.S.; Kothera, C.S.; Wereley, N.M. Wind tunnel testing of a helicopter rotor trailing edge flap actuated via pneumatic artificial muscles. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2011, 22, 1513–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, B.; Laloy, J.; Rotinat-Libersa, C. Compact and lightweight hydraulic actuation system for high performance millimeter scale robotic applications: Modeling and experiments. In Proceedings of the Smart Materials, Adaptive Structures and Intelligent Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 28 February–4 March 2010; pp. 405–411. [Google Scholar]

- Xiloyannis, M.; Cappello, L.; Khanh, D.B.; Yen, S.-C.; Masia, L. Modelling and design of a synergy-based actuator for a tendon-driven soft robotic glove. In Proceedings of the 2016 6th IEEE International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob), Singapore, 26–29 June 2016; pp. 1213–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, A.; Dvali, G.; Majorovits, B.; Millar, A.; Raffelt, G.; Redondo, J.; Reimann, O.; Simon, F.; Steffen, F. MADMAX Working Group. Dielectric haloscopes: A new way to detect axion dark matter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 091801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Fahaam, H.; Davis, S.; Nefti-Meziani, S. The design and mathematical modelling of novel extensor bending pneumatic artificial muscles (EBPAMs) for soft exoskeletons. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2018, 99, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Liang, Y.; Lin, X. A bionic cerebellar motion control model and its application in arm control. Sheng Xue Gong Cheng Xue Zhi J. Biomed. Eng. Shengwu Yixue Gongchengxue Zazhi 2020, 37, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar]

| Type of Pneumatic Muscle Actuator | Average Measured Critical Pressure (kPa) | Average Maximum Effective Deformation Pressure (kPa) | Average Contraction Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strip Balloon McKibben | |||

| Pneumatic Muscle Actuator | 189 | 175 | 29.58 |

| Rubber Hose McKibben | |||

| Pneumatic Muscle Actuator | 250 | 200 | 20.83 |

| Number of Nodes | Contraction Ratio in i-th Trial (%) | Average Contraction Ratio (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 26.31 | 25.26 | 24.73 | 24.21 | 26.84 | 25.47 |

| 3 | 29.72 | 27.56 | 28.10 | 28.64 | 27.02 | 28.21 |

| 4 | 30.27 | 30.48 | 31.35 | 32.43 | 30.81 | 31.07 |

| 5 | 25.94 | 25.41 | 24.32 | 24.86 | 24.94 | 25.29 |

| Bending Angle (°) | 4 | 12 | 14 | 18 | 20 | 23 | 29 | 36 | 38 | 42 | 46 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strip Balloon Pneumatic Muscle Inflation Pressure (kPa) | 75 | 85 | 95 | 105 | 115 | 125 | 135 | 145 | 155 | 165 | 170 |

| Rubber Hose Pneumatic Muscle Inflation Pressure (kPa) | 100 | 110 | 120 | 130 | 140 | 150 | 160 | 170 | 180 | 190 | 200 |

| Subject | Subject 1 | Subject 2 | Subject 3 | Subject 4 | Subject 5 | Subject 6 | Subject 7 | Subject 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forearm Length (cm) | 23.7 | 27.4 | 26.8 | 24.1 | 23.9 | 25.3 | 26.1 | 24.6 |

| Subject ID | Unassisted Torque (N·m) | Assisted Torque (N·m) | Torque Enhancement (N·m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.20 | 10.80 | 1.60 |

| 2 | 14.53 | 16.85 | 2.32 |

| 3 | 13.62 | 14.96 | 1.34 |

| 4 | 10.87 | 13.38 | 2.51 |

| 5 | 10.11 | 11.94 | 1.83 |

| 6 | 11.50 | 14.07 | 2.57 |

| 7 | 11.65 | 13.62 | 1.97 |

| 8 | 10.78 | 12.89 | 2.11 |

| Wearable Devices | Application | Actuation | Contraction (%) | Weight (kg) | Response Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xiloyannis et al. [25] | Wearable/Exoskeleton | PAM | ∼25 | ∼1.5 | 2 s |

| Caldwell et al. [26] | Wearable assist | PAM | 20–30 | – | 2 s |

| Al-Fahaam et al. [27] | Joint actuator | PAM | 20–25 | ∼1.0 | 2 s |

| Zhang et al. [28] | Soft joint system | PAM | ∼30 | – | 2 s |

| This work | Joint prototype | Braided PAM | 30.81 | 0.59 | 1.5 s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, H.; Zeng, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Zuo, Z.; Peng, Y. Bionic Design Based on McKibben Muscles and Elbow Flexion and Extension Assist Device. Actuators 2026, 15, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010021

Jiang H, Zeng Q, Jiang Y, Zuo Z, Peng Y. Bionic Design Based on McKibben Muscles and Elbow Flexion and Extension Assist Device. Actuators. 2026; 15(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Hong, Qingyi Zeng, Yang Jiang, Zihao Zuo, and Yanhong Peng. 2026. "Bionic Design Based on McKibben Muscles and Elbow Flexion and Extension Assist Device" Actuators 15, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010021

APA StyleJiang, H., Zeng, Q., Jiang, Y., Zuo, Z., & Peng, Y. (2026). Bionic Design Based on McKibben Muscles and Elbow Flexion and Extension Assist Device. Actuators, 15(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010021