Fuzzy Active Disturbance Rejection Control for Electro-Mechanical Actuator Based on Feedback Linearization

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A feedback linearization-based model transformation method is proposed to decouple uncertain disturbances into the same channel as control inputs, enabling effective compensation through control law design.

- An ESO is designed to estimate uncertainties in EMAs with its stability rigorously proven via Lyapunov stability theory.

- An ADRC control law based on the transformed model is developed, which is complemented by a fuzzy logic system featuring membership functions and rule bases. This system dynamically adjusts control gains according to EMA position-tracking errors and their derivatives, thereby enhancing tracking precision.

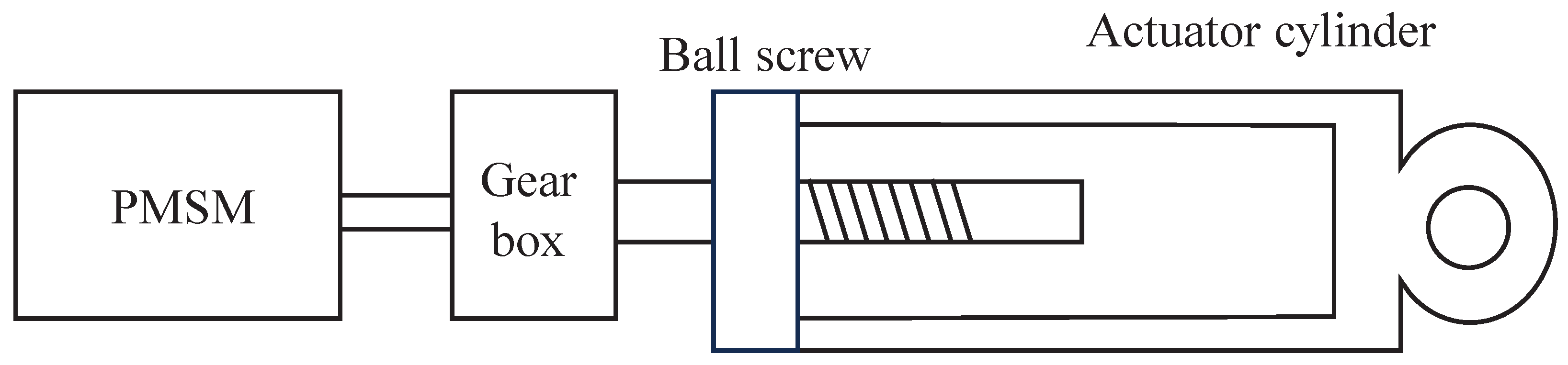

2. Electromechanical Actuator Model Development

2.1. Model of PMSM

2.2. Model of Mechanical Transmission Component

2.3. Model of Electromechanical Actuator

2.4. Feedback Linearization-Based Model Transform

3. Fuzzy ADRC Algorithm Design

- In the inner loop, two proportional–integral (PI) control methods regulate both d-axis and q-axis currents to achieve reference tracking, thereby boosting the current-loop bandwidth for stringent dynamic performance specifications. Exploiting the decoupling between the d-axis and q-axis current loops controller in an FOC, the control scheme adopts to streamline implementation while maintaining torque regulation via .

- In the outer loop, an active disturbance rejection control (ADRC) strategy is proposed based on feedback linearization, where the desired command current input is calculated using the state feedback of a PMSM and the estimation of disturbance from an ESO, with control law gains adaptively optimized via a fuzzy logic inference mechanism.

3.1. ESO for Uncertain External Torque Estimation

3.2. Fuzzy ADRC Based on Transformed Model

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Displacement Step Tracking Results

- Method 1: PID control method.

- Method 2: Feedback linearization method without fuzzy adaption.

- Proposed: The fuzzy ADRC method based on feedback linearization.

4.1.1. Step Torque Disturbance Results

4.1.2. Sinusoidal Torque Disturbance Results

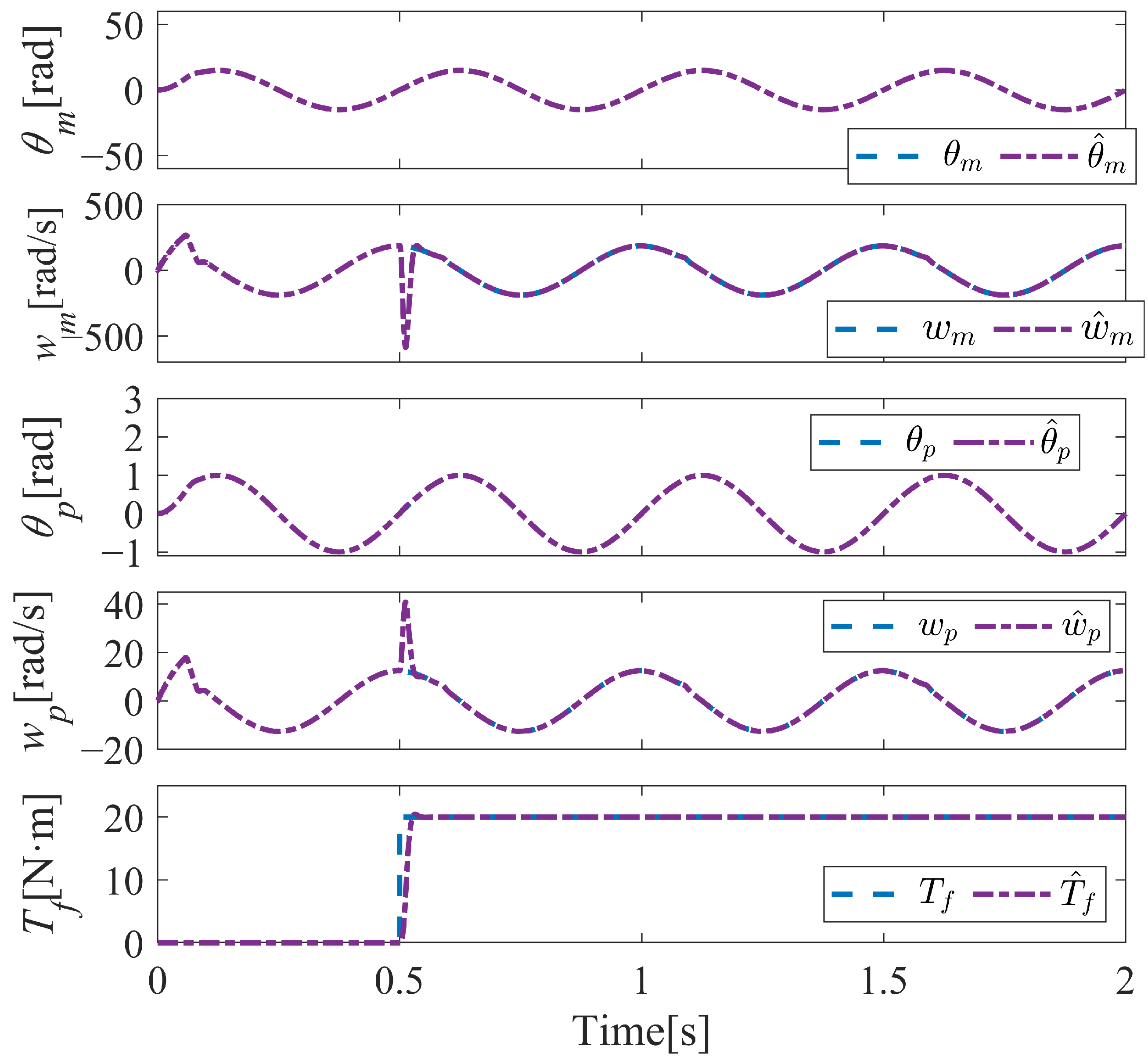

4.2. Displacement Sine Curve Tracking Results

4.2.1. Constant Torque Disturbance Results

4.2.2. Sine Torque Disturbance Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Shang, Y.; Jiao, Z.; Lin, Y.; Wu, S.; Li, X. Analysis of the dynamic performance of an electro-hydrostatic actuator and improvement methods. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2018, 31, 2312–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Cheng, X.; Ouyang, Q.; Lv, C.; Xu, W.; Wang, Z. Disturbance compensation-based feedback linearization control for air rudder electromechanical servo systems. Asian J. Control. 2025, 27, 2255–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Su, H. Research on Compound Sliding Mode Control of a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor in Electromechanical Actuators. Energies 2021, 14, 7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Shi, Z.; Yu, B.; Qi, H. Research on the EMA Control Method Based on Transmission Error Compensation. Energies 2024, 17, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Du, J. Adaptive Position Control Strategy of SRM-Based EMA System for Precision Position Tracking. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 4680–4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Xiong, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, D. Research on improved control method of electromechanical actuation. J. Eng. 2018, 2018, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Ali, A.W.; Abdul Razak, F.A.; Hayima, N. A Review on The AC Servo Motor Control Systems. ELEKTRIKA-J. Electr. Eng. 2020, 19, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, S.; Hu, H. PID Controller for PMSM Speed Control Based on Improved Quantum Genetic Algorithm Optimization. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 61091–61102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, Y.K.; Bhandari, P. Control of the BLDC Motor Using Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm for Tuning PID Parameters. Arch. Adv. Eng. Sci. 2023, 2, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Duan, J.; Ouyang, Q. Control strategy of electro-mechanical actuator based on deep reinforcement learning-PI control. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2022, 49, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Wu, Y.; Guo, J.; Chen, Q. Adaptive control and disturbance compensation for gear transmission servo systems with large-range inertia variation. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2022, 44, 700–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, Z.; Jia, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, J.G. Global position tracking control of PMSM servo system via internal model approach and experimental validations. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2022, 32, 9017–9033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Shao, J.; Yang, X. A compound control strategy combining velocity compensation with ADRC of electro-hydraulic position servo control system. ISA Trans. 2014, 53, 1910–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Cui, C.; Gu, S.; Wang, T.; Zhao, L. Trajectory Tracking Control of Pneumatic Servo System: A Variable Gain ADRC Approach. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 53, 6977–6986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Z.; Shi, W.; Duan, J.; Xu, L.; Zhou, M. Double-loop compensated active disturbance rejection control of electromechanical servo system based on composite disturbance observer. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 266, 126155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Luo, G.; Chen, Z.; Tu, W.; Qiu, C. A linear ADRC-based robust high-dynamic double-loop servo system for aircraft electro-mechanical actuators. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2019, 32, 2174–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Luo, G.; Duan, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, C. Adaptive LADRC-Based Disturbance Rejection Method for Electromechanical Servo System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2020, 56, 876–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, Q. A Compound Scheme Based on Improved ADRC and Nonlinear Compensation for Electromechanical Actuator. Actuators 2022, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.K. Nonlinear Systems; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Slotine, J.J.E.; Li, W.P. Applied Nonlinear Control; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

| NB | NM | NS | ZE | PS | PM | PB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB | PB | PB | PM | PM | PB | ZE | NS |

| NM | PB | PB | PM | PB | PB | NS | NS |

| NS | PM | PM | PM | PB | ZE | NM | NM |

| ZE | PM | PM | PS | ZE | NS | NM | NM |

| PS | PS | PS | ZE | NS | NS | NM | NB |

| PM | PS | ZE | NS | NM | NM | NB | NB |

| PB | ZE | ZE | NM | NM | NM | ZE | NM |

| NB | NM | NS | ZE | PS | PM | PB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB | PS | NS | NB | NB | NB | NS | ZE |

| NM | PS | NS | NB | NM | NB | NS | ZE |

| NS | ZE | NS | NM | NM | NS | NS | ZE |

| ZE | ZE | NS | NS | NS | NS | ZE | ZE |

| PS | ZE | ZE | ZE | ZE | ZE | PS | PB |

| PM | PB | PS | PS | PS | PS | PS | PB |

| PB | PB | PM | PM | PM | NM | PS | PS |

| Parameters | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| n | 15 | |

| N/m | ||

| P |

| Disturbance Types | Methods | MAE | IAE | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | Method 1 | 0.28791 | 0.1009 | 0.1294 |

| Method 2 | 0.20551 | 0.03990 | 0.05886 | |

| Proposed | 0.19158 | 0.01365 | 0.03645 | |

| Sinusoidal | Method 1 | 0.30145 | 0.1606 | 0.1635 |

| Method 2 | 0.20551 | 0.0158 | 0.04167 | |

| Proposed | 0.19158 | 0.01361 | 0.03629 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, H.; Jiang, J.; Xiao, X. Fuzzy Active Disturbance Rejection Control for Electro-Mechanical Actuator Based on Feedback Linearization. Actuators 2026, 15, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010018

Sun H, Jiang J, Xiao X. Fuzzy Active Disturbance Rejection Control for Electro-Mechanical Actuator Based on Feedback Linearization. Actuators. 2026; 15(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Huanyu, Ju Jiang, and Xi Xiao. 2026. "Fuzzy Active Disturbance Rejection Control for Electro-Mechanical Actuator Based on Feedback Linearization" Actuators 15, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010018

APA StyleSun, H., Jiang, J., & Xiao, X. (2026). Fuzzy Active Disturbance Rejection Control for Electro-Mechanical Actuator Based on Feedback Linearization. Actuators, 15(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010018