A Review of Robot-Assisted Needle-Insertion Approaches in Corneal Surgeries

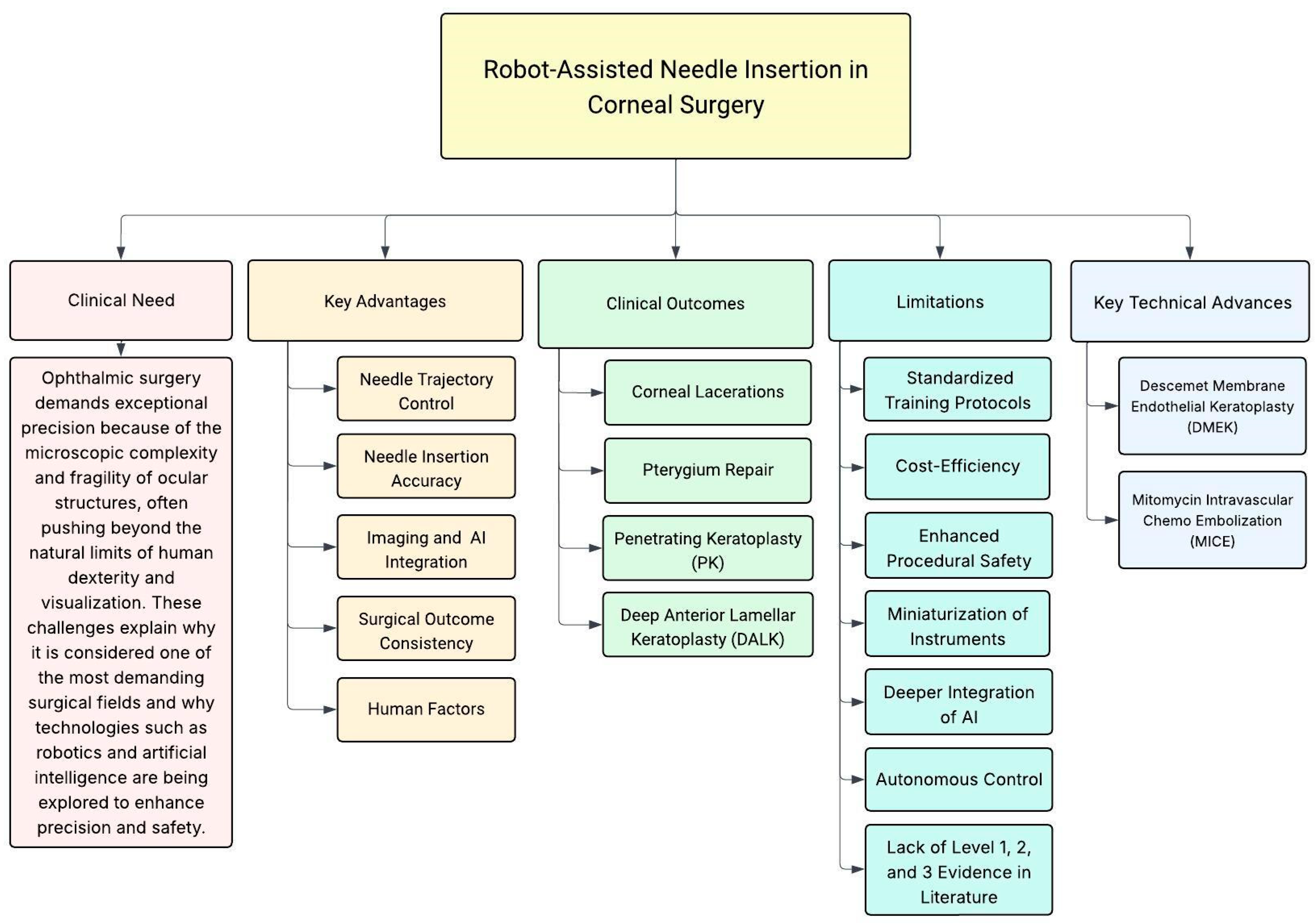

Abstract

1. Introduction

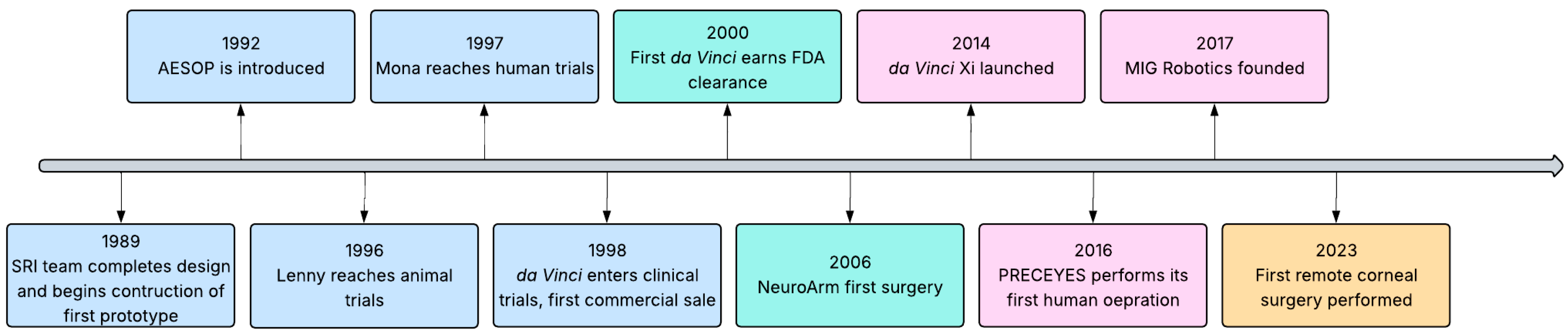

1.1. History

1.2. Clinical Need

1.3. Related Studies and Rationale

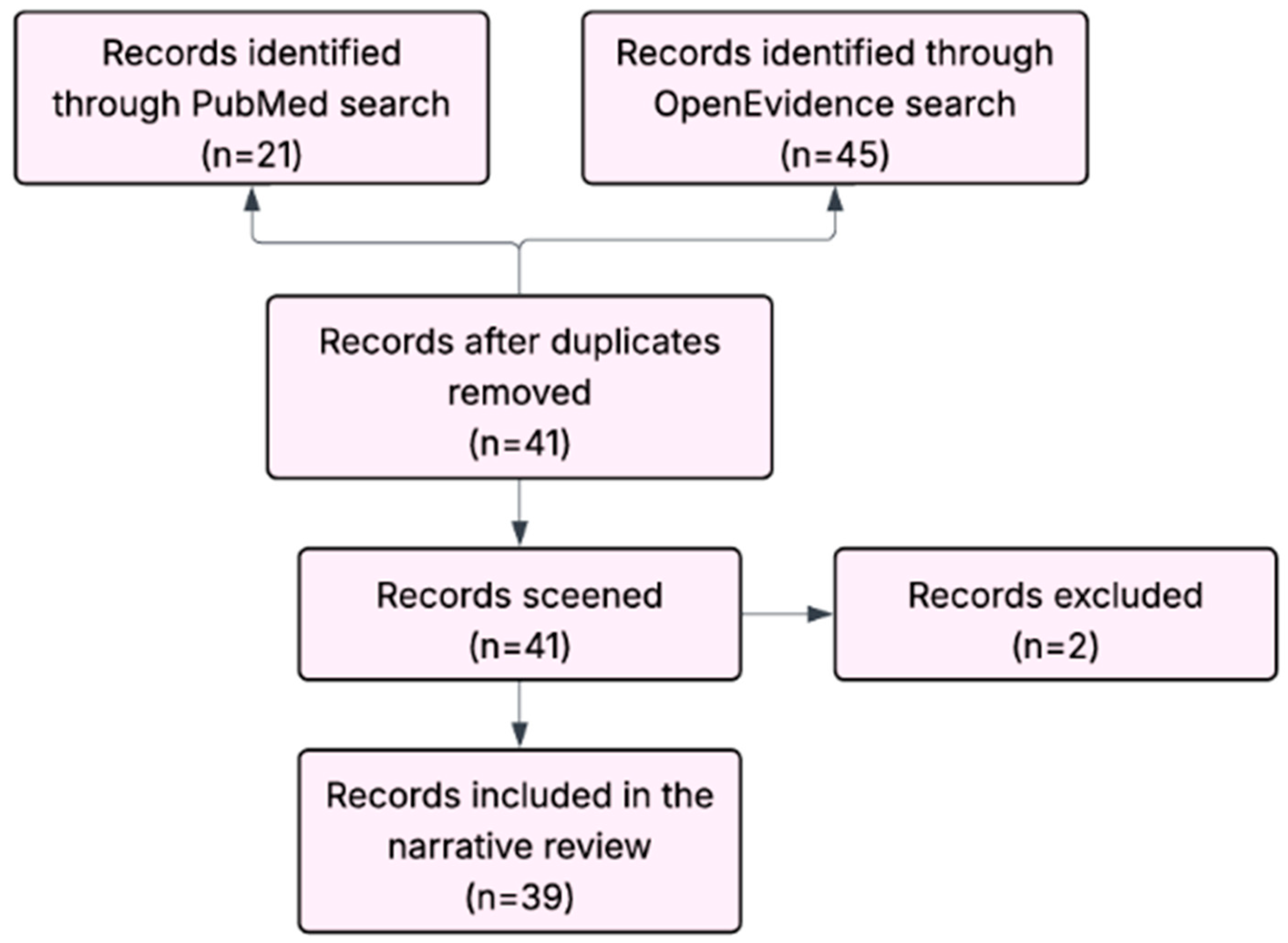

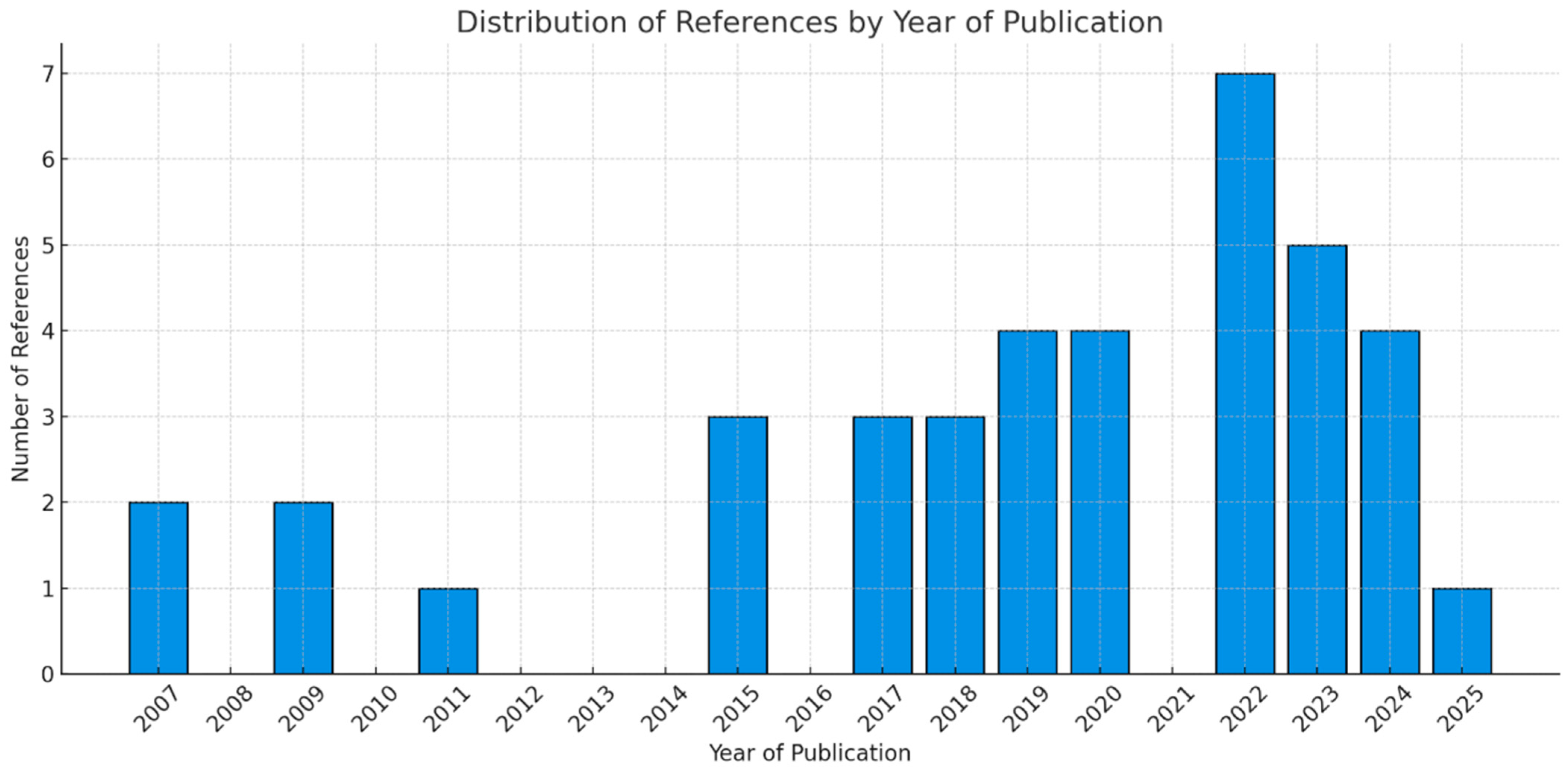

2. Methodology

2.1. Review Objective

2.2. Review Method

2.3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

- Focused on robotic assistance in ophthalmology with relevance to corneal surgery.

- Addressed needle insertion techniques, whether in ex vivo, animal, or clinical studies.

- Included either experimental validation, clinical applications, or authoritative re-views of technological advancements (e.g., from human trials, case series, or clinical evaluations).

- Literature was published in English.

- 5.

- Studies unrelated to robotic systems.

- 6.

- Studies that focused exclusively on non-corneal ophthalmic procedures.

- 7.

- Conceptual, simulation-only and digital prototyping works lacking experimental or clinical evaluation. Conference abstracts, theses, and preprints were also excluded.

2.4. Data Synthesis

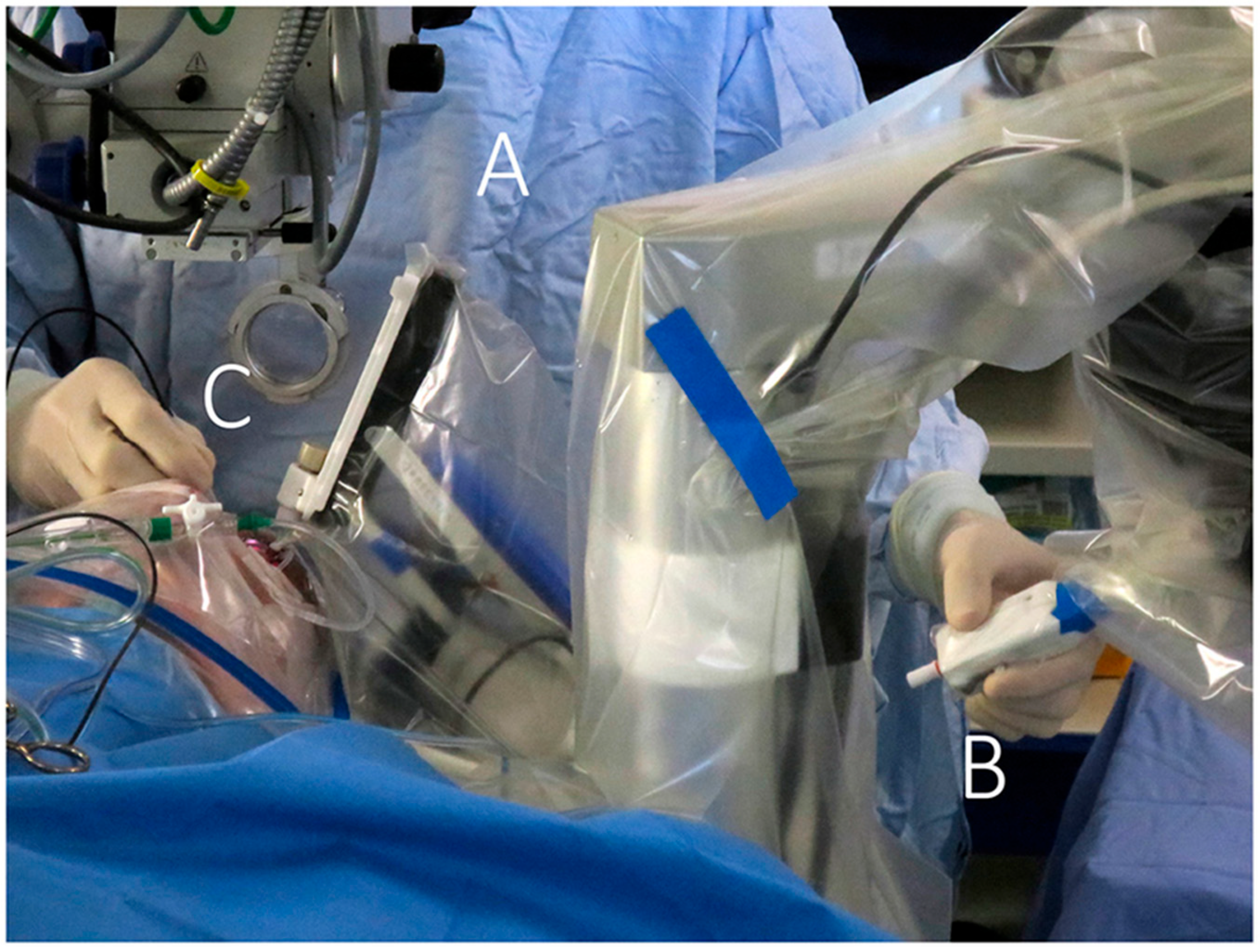

3. Robotic Technology Advancements in Corneal Procedures

3.1. Needle Trajectory Control

3.2. Needle Insertion Accuracy

3.3. Imagine Modalities and AI Integration

3.4. Surgical Outcomes Consistency

3.5. Human Factors

4. Clinical Outcomes

4.1. Corneal Lacerations

4.2. Pterygium Repair

4.3. Penetrating Keratoplasty

4.4. Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty

5. Limitations

5.1. Limitations of the Starte-of-the-Art

5.2. Limitations of Current Studies

5.3. Limitations of This Review

6. Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| DALK | Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty |

| DM | Descemet Membrane |

| DMEK | Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty |

| iOCT | Intraoperative Optical Coherence Tomography |

| KP | Penetrating Keratoplasty |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| MICE | Mitomycin Intravascular Chemo Embolization |

| MMC | Mitomycin-C |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| RAMSES | Robotic Assisted Microsurgical and Endoscopic Society |

| SC-OCT | Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography |

References

- Gerber, M.J.; Pettenkofer, M.; Hubschman, J.P. Advanced robotic surgical systems in ophthalmology. Eye 2020, 34, 1554–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Smet, M.D.; Naus, G.J.L.; Faridpooya, K.; Mura, M. Robotic-assisted surgery in ophthalmology. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 29, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourla, D.H.; Hubschman, J.P.; Culjat, M.; Tsirbas, A.; Gupta, A.; Schwartz, S.D. Feasibility study of intraocular robotic surgery with the da Vinci surgical system. Retina 2008, 28, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladha, R.; Caspers, L.E.; Willermain, F.; de Smet, M.D. Subretinal Therapy: Technological Solutions to Surgical and Immunological Challenges. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 846782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alafaleq, M. Robotics and cybersurgery in ophthalmology: A current perspective. J. Robot. Surg. 2023, 17, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzimichail, E.; Feltgen, N.; Motta, L.; Empeslidis, T.; Konstas, A.G.; Gatzioufas, Z.; Panos, G.D. Transforming the future of ophthalmology: Artificial intelligence and robotics’ breakthrough role in surgical and medical retina advances: A mini review. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1434241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, H.; MacLaren, R.E.; Cehajic-Kapetanovic, J. Robotising vitreoretinal surgeries. Eye 2025, 39, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.I.; Brand, T.C.; LaPorta, A.; Marescaux, J.; Satava, R.M. Origins of Robotic Surgery: From Skepticism to Standard of Care. JSLS J. Soc. Laparoendosc. Surg. 2018, 22, e2018.00039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, G.M.; Lindfield, D.; Sim, D.; Tsesmetzoglou, E.; Gauba, V.; Gartry, D.S.; Ghoussayni, S. Kinematic analysis of surgical dexterity in intraocular surgery. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2009, 127, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordachita, I.I.; de Smet, M.D.; Naus, G.; Mitsuishi, M.; Riviere, C.N. Robotic Assistance for Intraocular Microsurgery: Challenges and Perspectives. Proceedings of the IEEE. Inst. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2022, 110, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesthuis, R.J.; van Veen, Y.R.J.; Jahya, A.; Misra, S. Mechanics of needle-tissue interaction. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Francisco, CA, USA, 25–30 September 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 2557–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

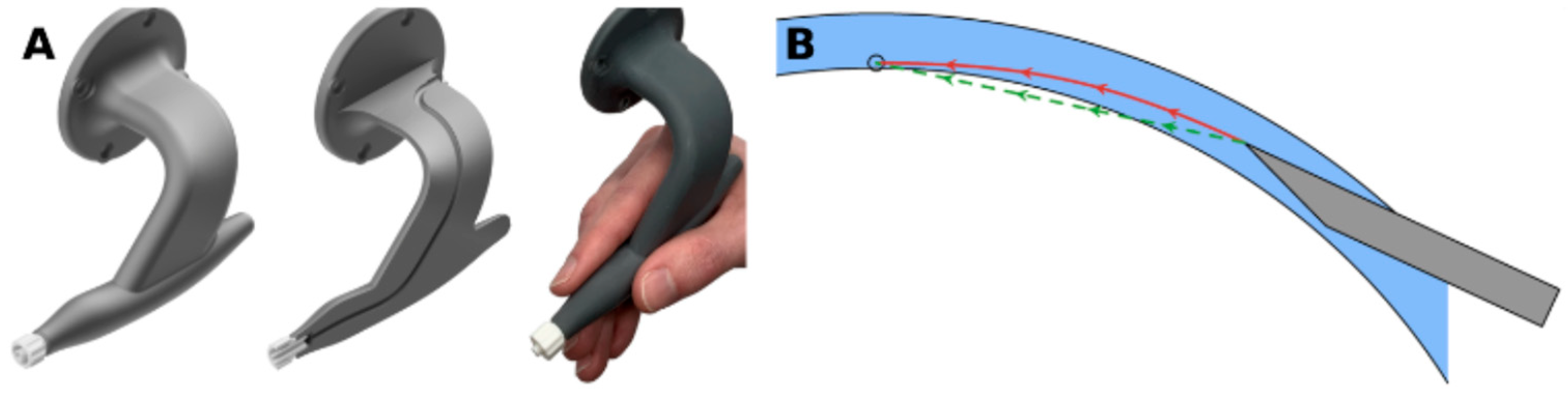

- Tsirbas, A.; Mango, C.; Dutson, E. Robotic ocular surgery. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourges, J.L.; Hubschman, J.P.; Burt, B.; Culjat, M.; Schwartz, S.D. Robotic microsurgery: Corneal transplantation. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2009, 93, 1672–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.; Misra, S. Biomechanics-Based Curvature Estimation for Ultrasound-Guided Flexible Needle Steering in Biological Tissues. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 43, 1716–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourcier, T.; Nardin, M.; Sauer, A.; Gaucher, D.; Speeg, C.; Mutter, D.; Marescaux, J.; Liverneaux, P. Robot-Assisted Pterygium Surgery: Feasibility Study in a Nonliving Porcine Model. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2015, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourcier, T.; Chammas, J.; Becmeur, P.H.; Danan, J.; Sauer, A.; Gaucher, D.; Liverneaux, P.; Mutter, D. Robotically Assisted Pterygium Surgery: First Human Case. Cornea 2015, 34, 1329–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Bae, J.K.; Ahn, Y.; Kim, H.; Choi, G.; Yoo, Y.S.; Joo, C.K.; Moon, S.; Jung, W. Lamellar keratoplasty using position-guided surgical needle and M-mode optical coherence tomography. J. Biomed. Opt. 2017, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.; Zhong, Y.; Gu, C. Master-slave robotic system for needle indentation and insertion. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2017, 22 (Suppl. S1), 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chammas, J.; Sauer, A.; Pizzuto, J.; Pouthier, F.; Gaucher, D.; Marescaux, J.; Mutter, D.; Bourcier, T. Da Vinci Xi Robot-Assisted Penetrating Keratoplasty. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2017, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.L.; Xue, K.; Meenink, H.C.M.; Beelen, M.J.; Naus, G.J.L.; Simunovic, M.P.; Latasiewicz, M.; Farmery, A.D.; de Smet, M.D.; MacLaren, R.E. First-in-human study of the safety and viability of intraocular robotic surgery. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirunavukarasu, A.J.; Hu, M.L.; Foster, W.P.; Xue, K.; Cehajic-Kapetanovic, J.; MacLaren, R.E. Robot-Assisted Eye Surgery: A Systematic Review of Effectiveness, Safety, and Practicality in Clinical Settings. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-J.; Lu, J.-L.; Zhang, Y.-D.; Zhang, H.; Pei, Y.-Y. Structural design and puncture control of insertion robot for FBG embedded cannula flexible needle. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 79295–79304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, G. Ultrasound Probe and Hand-Eye Calibrations for Robot-Assisted Needle Biopsy. Sensors 2022, 22, 9465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

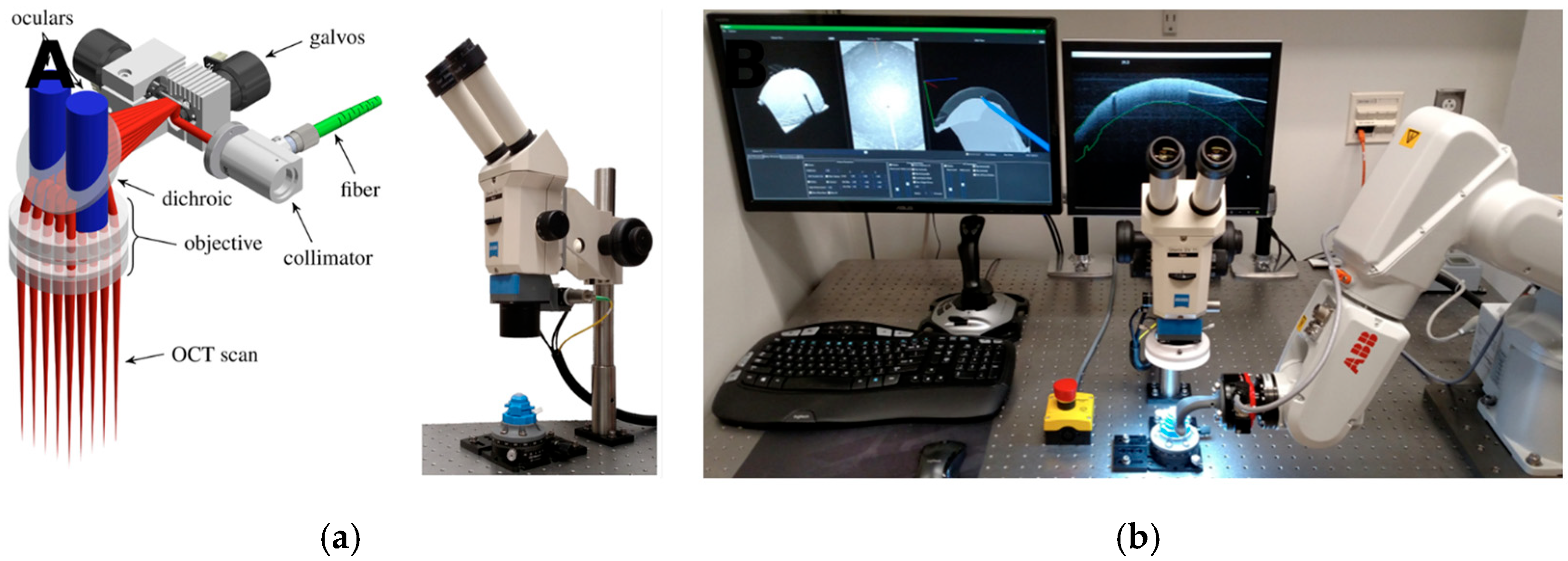

- Tian, Y.; Draelos, M.; McNabb, R.P.; Hauser, K.; Kuo, A.N.; Izatt, J.A. Optical coherence tomography refraction and optical path length correction for image-guided corneal surgery. Biomed. Opt. Express 2022, 13, 5035–5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Sarfaraz, N.R.; Gensheimer, W.G.; Krieger, A.; Kang, J.U. Demonstration of Optical Coherence Tomography Guided Big Bubble Technique for Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty (DALK). Sensors 2020, 20, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldebasi, T.; Gangadharan, S.; Alshammari, Y.S.; Alruhaimi, S.S.; Alrashid, S.O.; Ardah, H.; Shahrani, J.A.; Shahrani, S.A.; Badri, M.; Alfardan, F. Comparison of clinical outcomes, complications and patient satisfaction following deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024, 24, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, W.; Tang, G.; Tian, Y.; Draelos, M.; Izatt, J.; Kuo, A.; Hauser, K. Data-Driven Modelling and Control for Robot Needle Insertion in Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Jablonka, A.M.; Maierhofer, N.A.; Roodaki, H.; Eslami, A.; Maier, M.; Nasseri, M.A.; Zapp, D. Comparison of Robot-Assisted and Manual Cannula Insertion in Simulated Big-Bubble Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

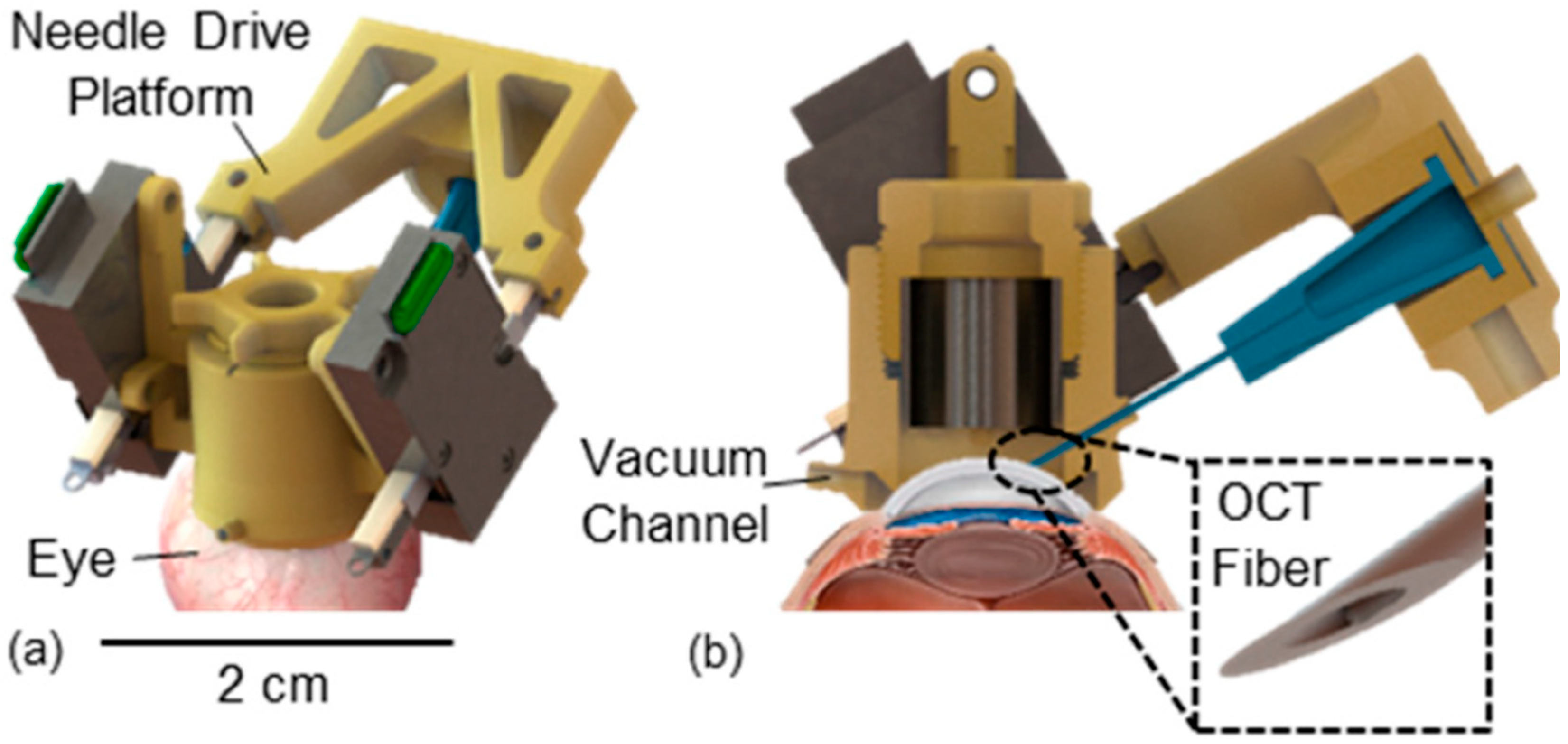

- Opfermann, J.D.; Wang, Y.; Kaluna, J.; Suzuki, K.; Gensheimer, W.; Krieger, A.; Kang, J.U. Design and Evaluation of an Eye Mountable AutoDALK Robot for Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty. Micromachines 2024, 15, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faridpooya, K.; van Romunde, S.H.M.; Manning, S.S.; van Meurs, J.C.; Naus, G.J.L.; Beelen, M.J.; Meenink, T.C.M.; Smit, J.; de Smet, M.D. Randomised controlled trial on robot-assisted versus manual surgery for pucker peeling. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 50, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, F.; Somfai, G.M.; Heussen, F.M.; Eberle, A.; de Smet, M.D.; Becker, M.D. Robot-Assisted Epiretinal Membrane Peeling: A Prospective Assessment of Pre- and Intra-Operative Times and of Surgeons’ Subjective Perceptions. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarmatori, N.; Pellegrini, M.; Nasini, F.; Talli, P.M.; Sarti, L.; Mura, M. The State of Intraoperative OCT in Vitreoretinal Surgery: Recent Advances and Future Challenges. Tomography 2023, 9, 1649–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.K.; Sharma, V. Robotics and ophthalmology: Are we there yet? Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 67, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, B.; Draelos, M.; Zhou, K.; Qian, R.; Kuo, A.; Konidaris, G.; Hauser, K.; Izatt, J. Optical Coherence Tomography-Guided Robotic Ophthalmic Microsurgery via Reinforcement Learning from Demonstration. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2020, 36, 1207–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draelos, M.; Tang, G.; Keller, B.; Kuo, A.; Hauser, K.; Izatt, J.A. Optical Coherence Tomography Guided Robotic Needle Insertion for Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty. IEEE Trans. Bio-Med. Eng. 2020, 67, 2073–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.; Patel, N.; He, C.; Gehlbach, P.; Kobilarov, M.; Iordachita, I. Adaptive Control of Sclera Force and Insertion Depth for Safe Robot-Assisted Retinal Surgery. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; Volume 2019, pp. 9073–9079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takács, B.; Haidegger, T. Autonomous applied robotics: Ultrasound-based robot-assisted needle insertion system concept and development. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 15th International Conference of System of Systems Engineering (SoSE), Budapest, Hungary, 2–4 June 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hos, D.; Matthaei, M.; Bock, F.; Maruyama, K.; Notara, M.; Clahsen, T.; Hou, Y.; Le, V.N.H.; Salabarria, A.C.; Horstmann, J.; et al. Immune reactions after modern lamellar (DALK, DSAEK, DMEK) versus conventional penetrating corneal transplantation. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2019, 73, 100768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeil, A.; Cazzato, R.L.; Barbé, L.; De Marini, P.; Chiang, J.B.; Garnon, J.; Renaud, P.; Gangi, A. Robotically Assisted CBCT-Guided Needle Insertions: Preliminary Results in a Phantom Model. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2019, 42, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 230-2:2014; Test Code for Machine Tools—Part 2: Determination of Accuracy and Repeatability of Positioning of Numerically Controlled Axes. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Hohmann, E.; Feldman, M.; Hunt, T.J.; Cote, M.P.; Brand, J.C. Research Pearls: How Do We Establish the Level of Evidence? Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2018, 34, 3271–3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poh, S.S.J.; Sia, J.T.; Yip, M.Y.T.; Tsai, A.S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Tan, G.S.W.; Weng, C.Y.; Kadonosono, K.; Kim, M.; Yonekawa, Y.; et al. Artificial Intelligence, Digital Imaging, and Robotics Technologies for Surgical Vitreoretinal Diseases. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2024, 8, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blavakis, E.; Kecik, M.; Panos, G.D.; Thumann, G.; Massa, H. Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty Graft Preparation Using the Liquid Bubble Technique with Subtrabecular Hydrodissection: A Retrospective Real-Life Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullayev, E.; Gorovoy, M.; Sprehe, N. Descemet’s membrane (DM) grafts preparations for DMEK with a liquid ‘blister’ separation method. In Proceedings of the Fall Education Symposium, Tampa, FL, USA, 14 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Solley, K.D.; Berges, A.J.; Phillips, E.; Ding, A.S.; Diaz, C.M.; Pramanik, S.; Yazdi, Y.; Parikh, K.S. DescePrep Significantly Increases Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty Processing Efficiency and Success Rate in Diabetic Human Donor Corneas in Comparison with Manual Dissection. Cornea 2022, 41, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szurman, P.; Januschowski, K.; Rickmann, A.; Damm, L.J.; Boden, K.T.; Opitz, N. Novel liquid bubble dissection technique for DMEK lenticule preparation. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2016, 254, 1819–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, M.; Borroni, D.; Ruzza, A.; Levis, H.J.; Ferrari, S.; Ponzin, D.; Romano, V. A comparative study on different Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty graft preparation techniques. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018, 96, e718–e726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhogal, M.; Balda, M.S.; Matter, K.; Allan, B.D. Global cell-by-cell evaluation of endothelial viability after two methods of graft preparation in Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 100, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimouni, M.; Ouano, D. Initial outcomes of mitomycin intravascular chemoembolization (MICE) for corneal neovascularization. Int. Ophthalmol. 2022, 42, 2407–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velazquez, D.C.; Ortiz-Morales, G.; Vera-Duarte, G.R.; Navas, A.; Ramirez-Miranda, A.; Graue-Hernandez, E.O. Mitomycin Intravascular Chemoembolization for Corneal Neovascularization. Cornea 2024, 44, 965–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, S.; Cheung, A.Y. Treatment of Corneal Neovascularization Before Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty. Cornea 2024, 44, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangu, N.; Riaz, K.M. Mitomycin intravascular chemoembolization (MICE) to treat corneal vascularization prior to penetrating keratoplasty. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2024, 33, 101993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addeen, S.Z.; Oyoun, Z.; Alfhaily, H.; Anbari, A. Outcomes of mitomycin C intravascular chemoembolization (MICE) in refractory corneal neovascularization after failed keratoplasty. Digit. J. Ophthalmol. DJO 2023, 29, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Review | Focus | Limitations for Corneal Surgery |

|---|---|---|

| de Smet (2018) [2] | Broad overview of robotic-assisted ophthalmology; transition from general-purpose to specialized systems | Emphasis on vitreoretinal surgery; corneal procedures mentioned only in passing |

| Gerber (2020) [1] | Advanced robotic surgical systems across ophthalmology | Highlighted clinical integration in posterior segment; little detail on corneal applications |

| Iordachita (2022) [10] | Technical challenges in intraocular microsurgery (force sensing, tremor elimination, control strategies) | Engineering-oriented; not subspecialty-specific; corneal surgery not systematically addressed |

| Alafaleq (2023) [5] | Robotics and cybersurgery in ophthalmology | Focused on a general perspective; lacked procedure-specific analysis, especially in the cornea |

| Chatzimichail (2024) [6] | AI and robotics in medical retina | Posterior segment—focused; no coverage of corneal needle-based interventions |

| Review | Procedure | Setting | Robot | Outcomes | Findings | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsirbas 2007 [12] | Corneal laceration repair | 5 ex vivo porcine corneas | DaVinci | Feasibility of robotic corneal suturing, improved visualization of needle trajectory. | Demonstrated precision, but instruments were too large for optimal corneal handling. | IV |

| Bourcier 2015 [16] | Pterygium pair | 12 ex vivo ocular models | DaVinci Si HD | Mean operative time 36 min, precise ocular maneuvers, no complications. | Feasibility confirmed; robotic system enabled stable and precise needle control. | IV |

| Bourcier 2015 [16] | Pterygium Repair | 2 procedures in 1 in vivo human corneas | DaVinci Si HD | No complications, uneventful recovery. | First human case of robotic-assisted pterygium repair; precision and dexterity confirmed. | IV |

| Bourges 2009 [13] | Penetrating Keratoplasty | 3 ex vivo porcine and 2 ex vivo human corneas | DaVinci Si HD | Demonstrated feasibility but poor visualization and limited maneuverability. | Identified limitations of Da Vinci for ophthalmic tasks. | IV |

| Chammas 2017 [19] | Penetrating Keratoplasty | 12 ex vivo human cornea transplant models | DaVinci Xi | Demonstrate feasibility with precise suture placement confirmed with OCT, operative time 43.4 min. | Improved visualization and ergonomics, feasible for PK. | IV |

| Draelos 2020 [35] | DALK | 120 insertions spread across 5 ex vivo human corneas | Cooperative and automated robot with volumetric OCT | Automated mode error 37 μm vs. 108 μm manual; 0% vs. 20% perforation. | Robotics + OCT significantly improved safety and accuracy. | IV |

| Edwards 2022 [27] | DALK | 48 insertions across 6 ex vivo human corneas | 20 model-based robot and 20 open-loop robot | Mean error of model-based robot vs. open-loop robot: 27 μm vs. 76 μm. | Model-based robot had significantly lower error. | IV |

| Zhao 2023 [28] | DALK | 48 ex vivo porcine corneas | Robot assisted insertion with OCT-guided cannula | Robot-assisted vs. manual method insertion depth of corneal thickness: 89.3% ± 2.1 vs. 81.7% ± 6.8. Robot-assisted vs. manual method perforation rate: 0% vs. 20%. | Robot showed a more consistent performance and lower rate of perforation. | IV |

| Opfemann 2024 [29] | DALK | 9 ex vivo porcine corneas | AutoDALK | AutoDALK vs. manual method insertion depth of corneal thickness: 84.8% ± 1.5 vs. 87.0% ± 7.0. AutoDALK vs. manual method perforation rate: 0% vs. 25%. | Autonomous approach is feasible; robot showed a more consistent performance and lower rate of perforation. | IV |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, E.-R.; Ramos, A.C.; Beschi, G.; Rocha, G.; Hooshiar, A. A Review of Robot-Assisted Needle-Insertion Approaches in Corneal Surgeries. Actuators 2025, 14, 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120587

Zhang E-R, Ramos AC, Beschi G, Rocha G, Hooshiar A. A Review of Robot-Assisted Needle-Insertion Approaches in Corneal Surgeries. Actuators. 2025; 14(12):587. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120587

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Eliana-Ruobing, Andres C. Ramos, Giacomo Beschi, Guillermo Rocha, and Amir Hooshiar. 2025. "A Review of Robot-Assisted Needle-Insertion Approaches in Corneal Surgeries" Actuators 14, no. 12: 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120587

APA StyleZhang, E.-R., Ramos, A. C., Beschi, G., Rocha, G., & Hooshiar, A. (2025). A Review of Robot-Assisted Needle-Insertion Approaches in Corneal Surgeries. Actuators, 14(12), 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120587