HASEL Actuators Activated with a Multi-Channel Low-Cost High Voltage Power Supply

Abstract

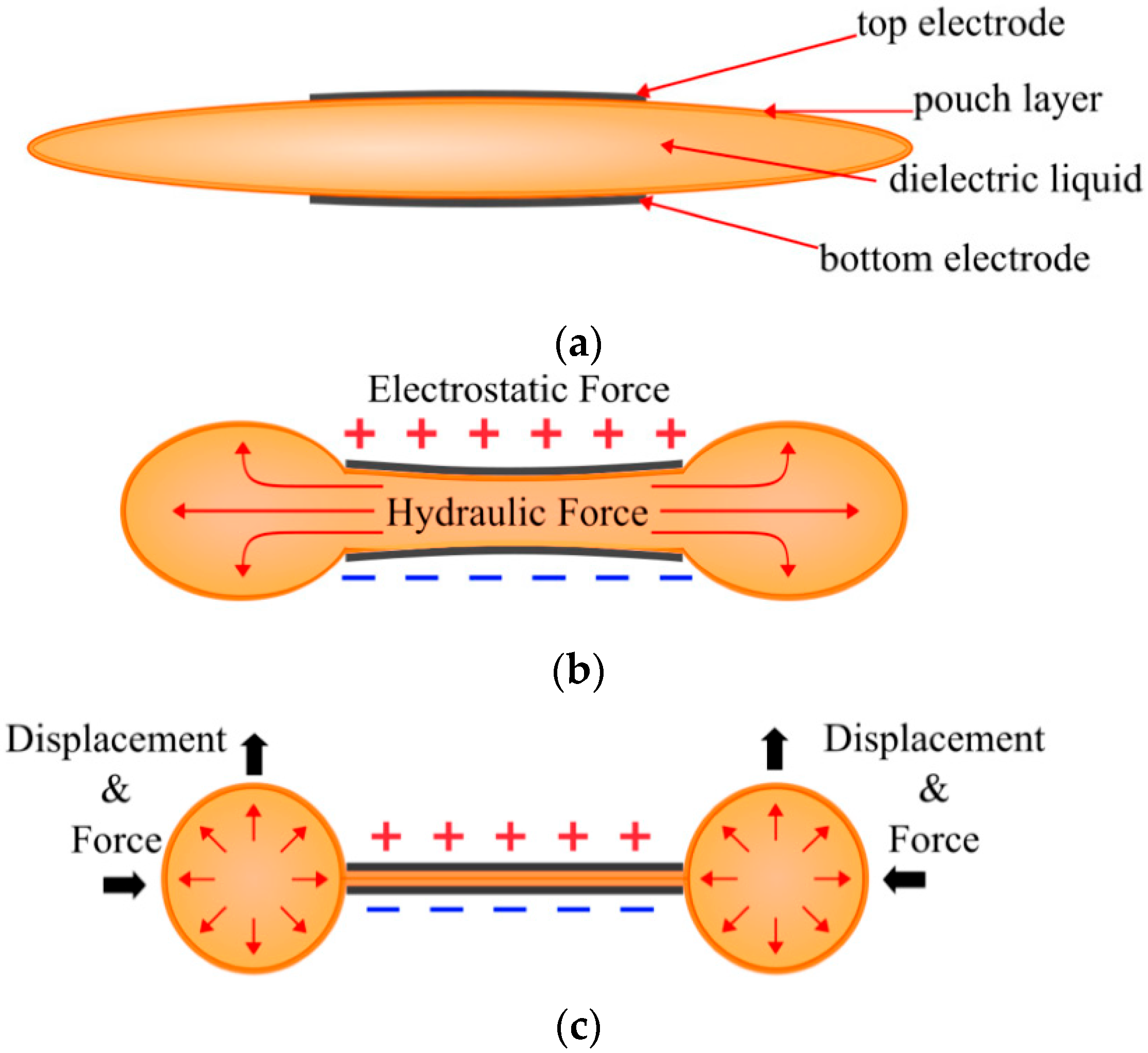

1. Introduction

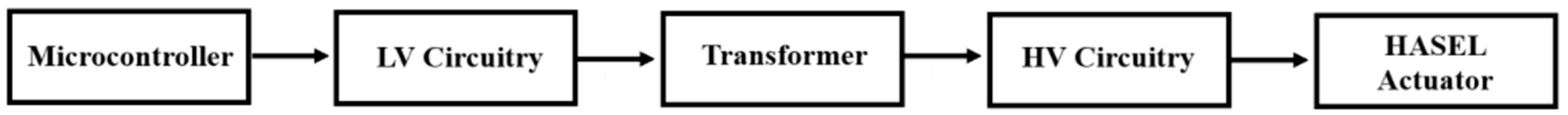

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. LV Design

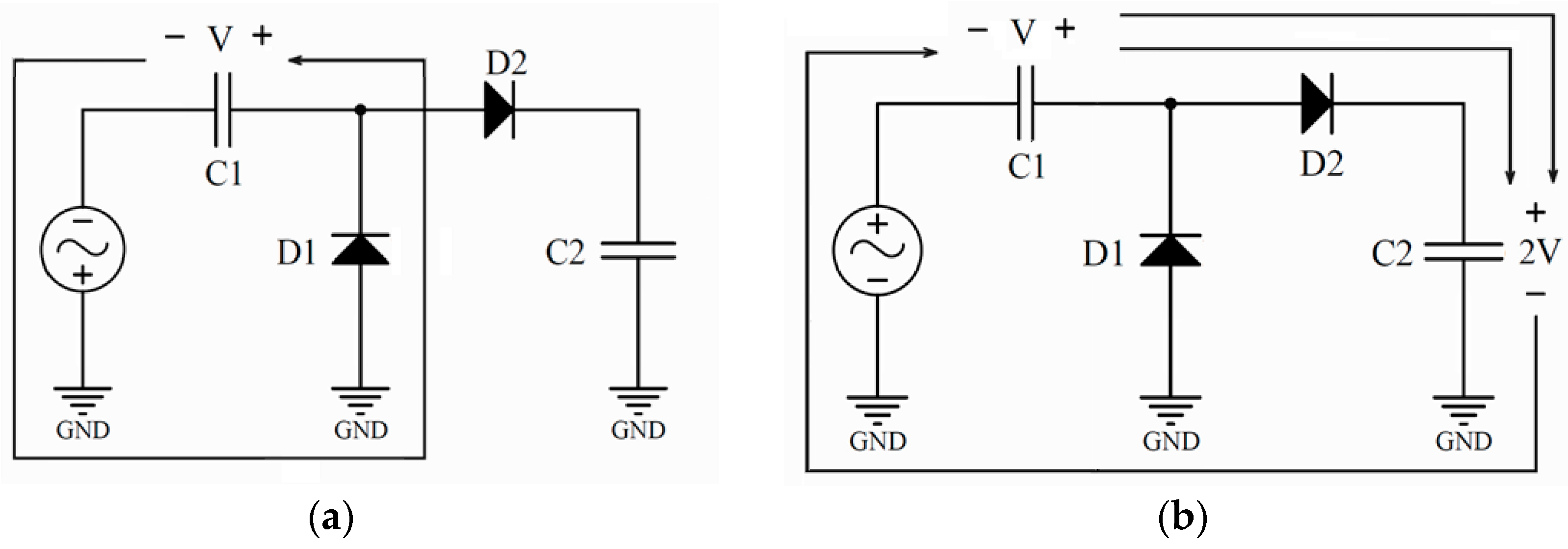

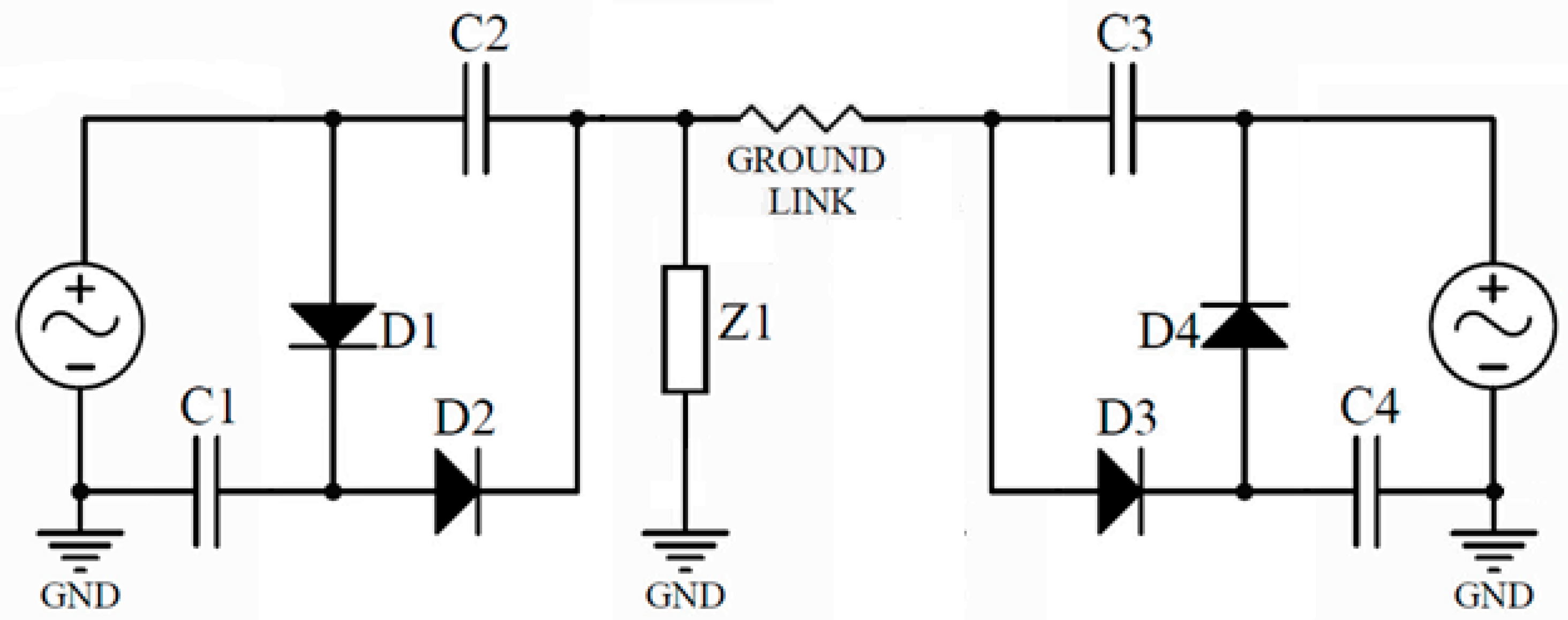

2.2. HV Design

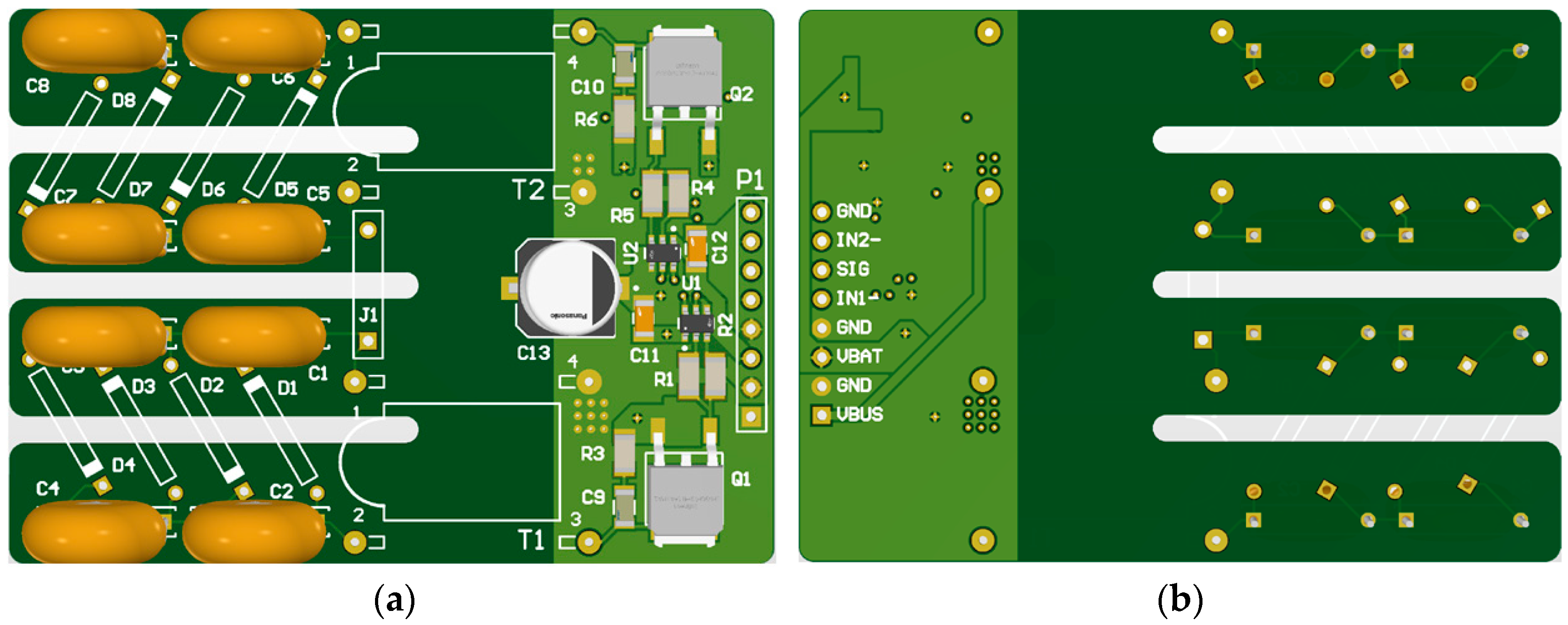

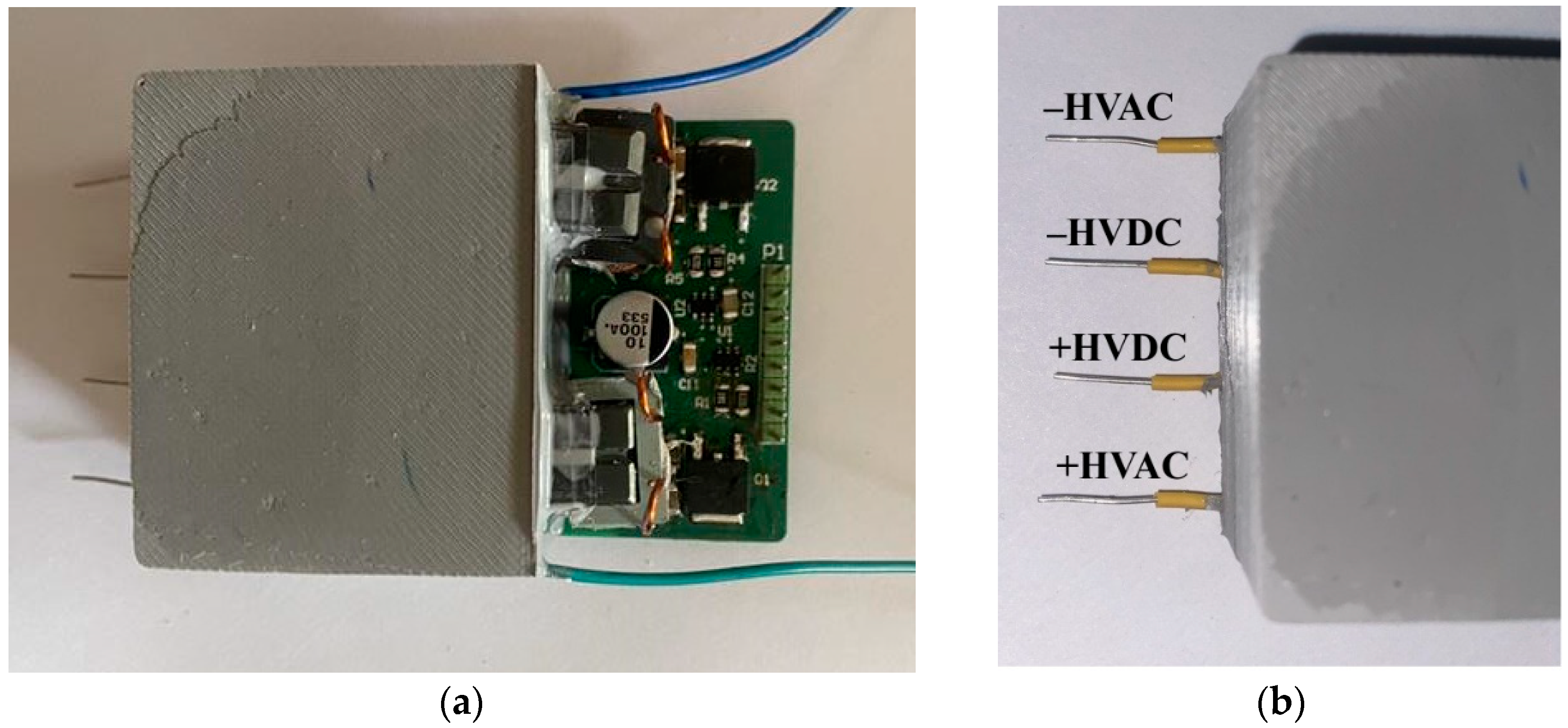

2.3. PCB Design and Assembly

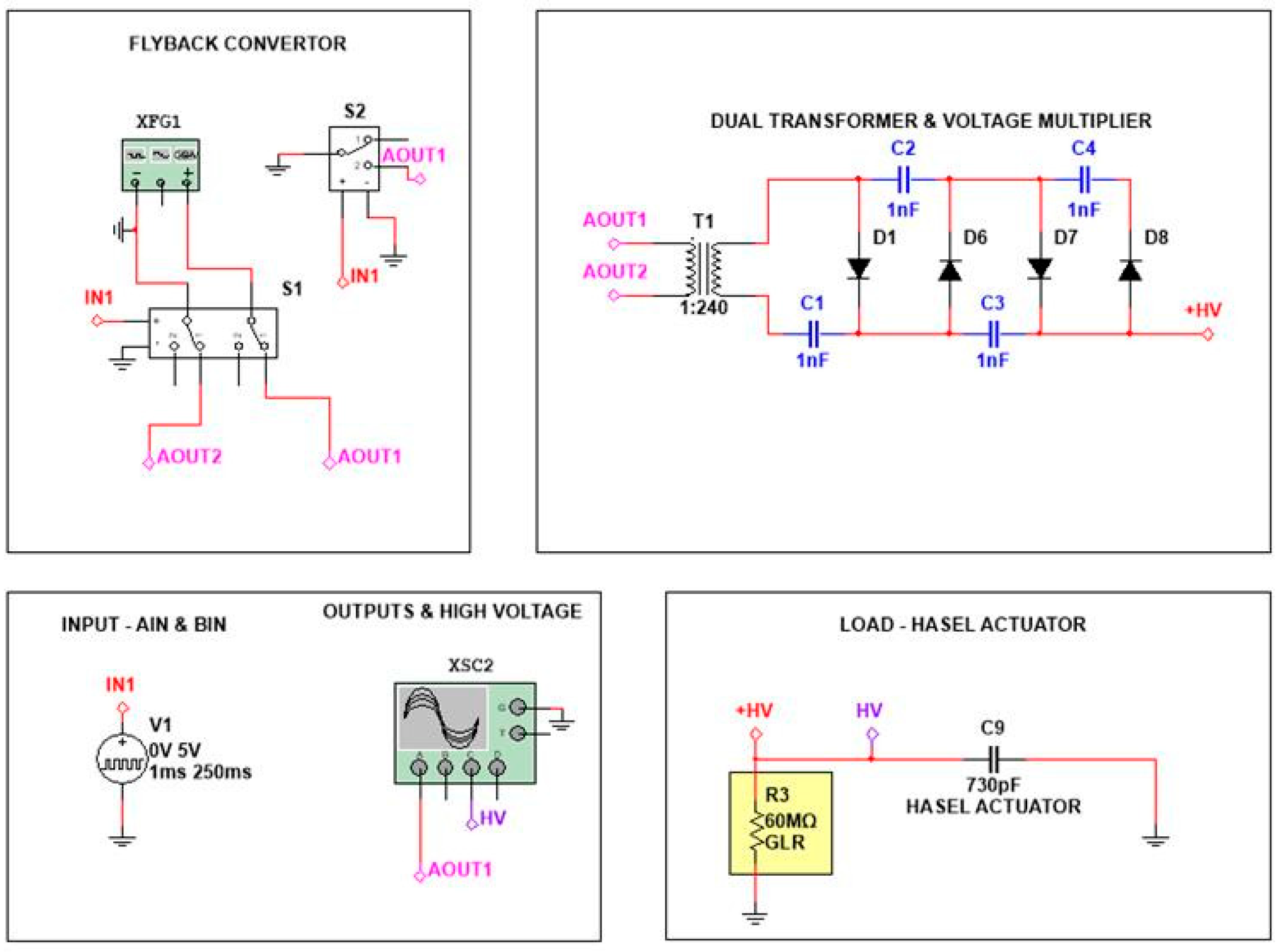

2.4. Simulation Setup

3. Results

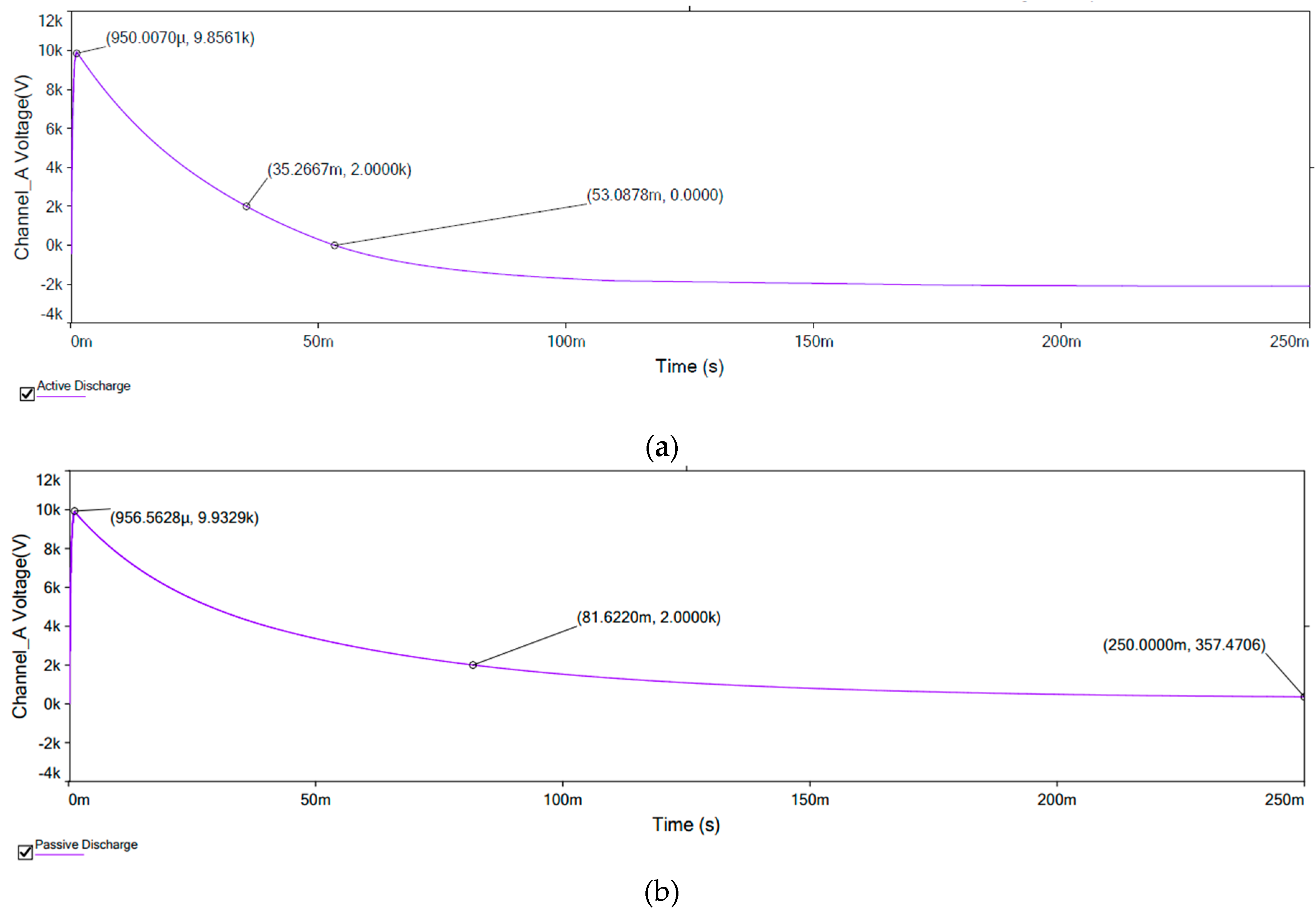

3.1. Simulated Results

3.2. Tested Results

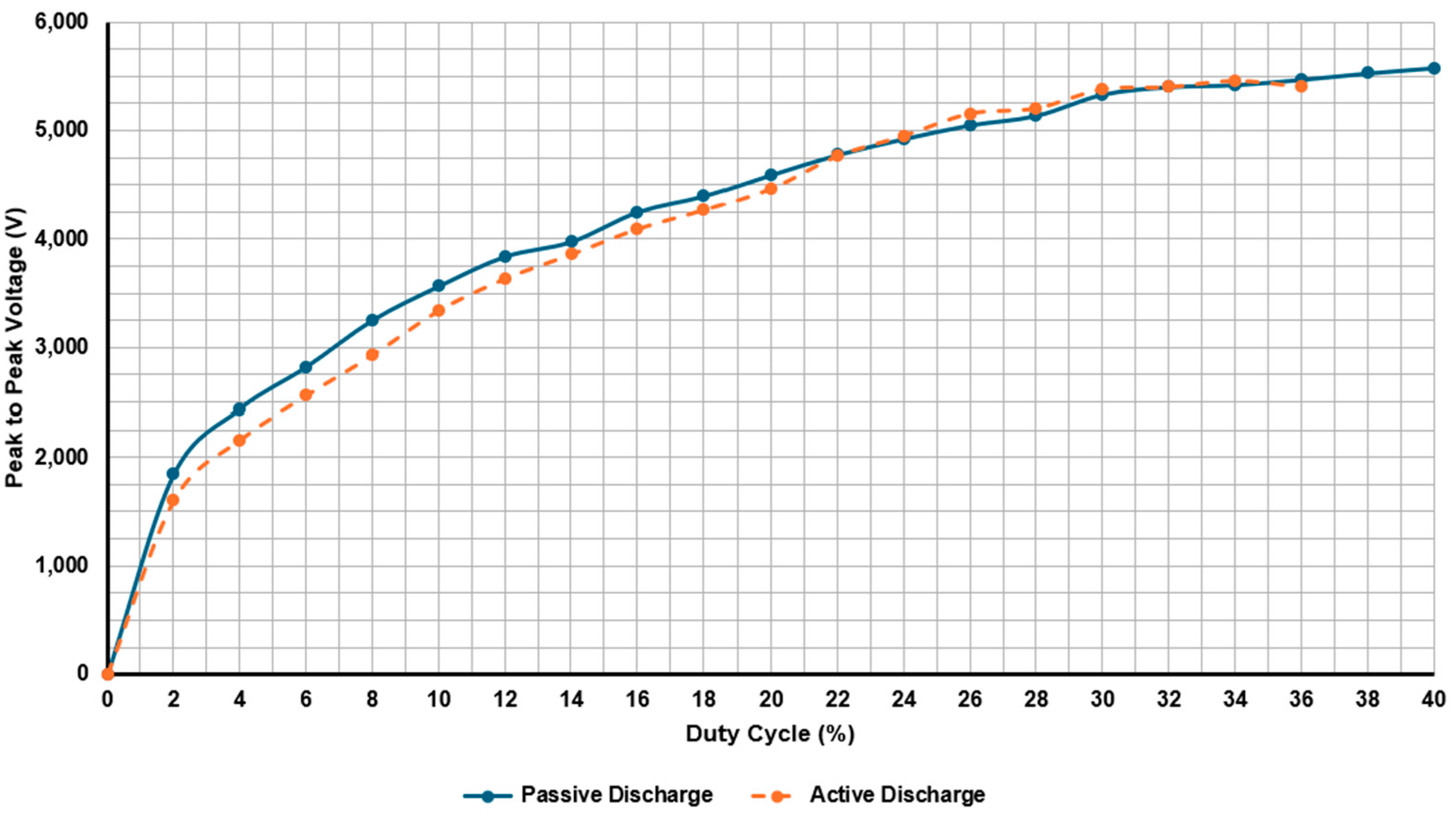

3.2.1. Positive HVDC Output

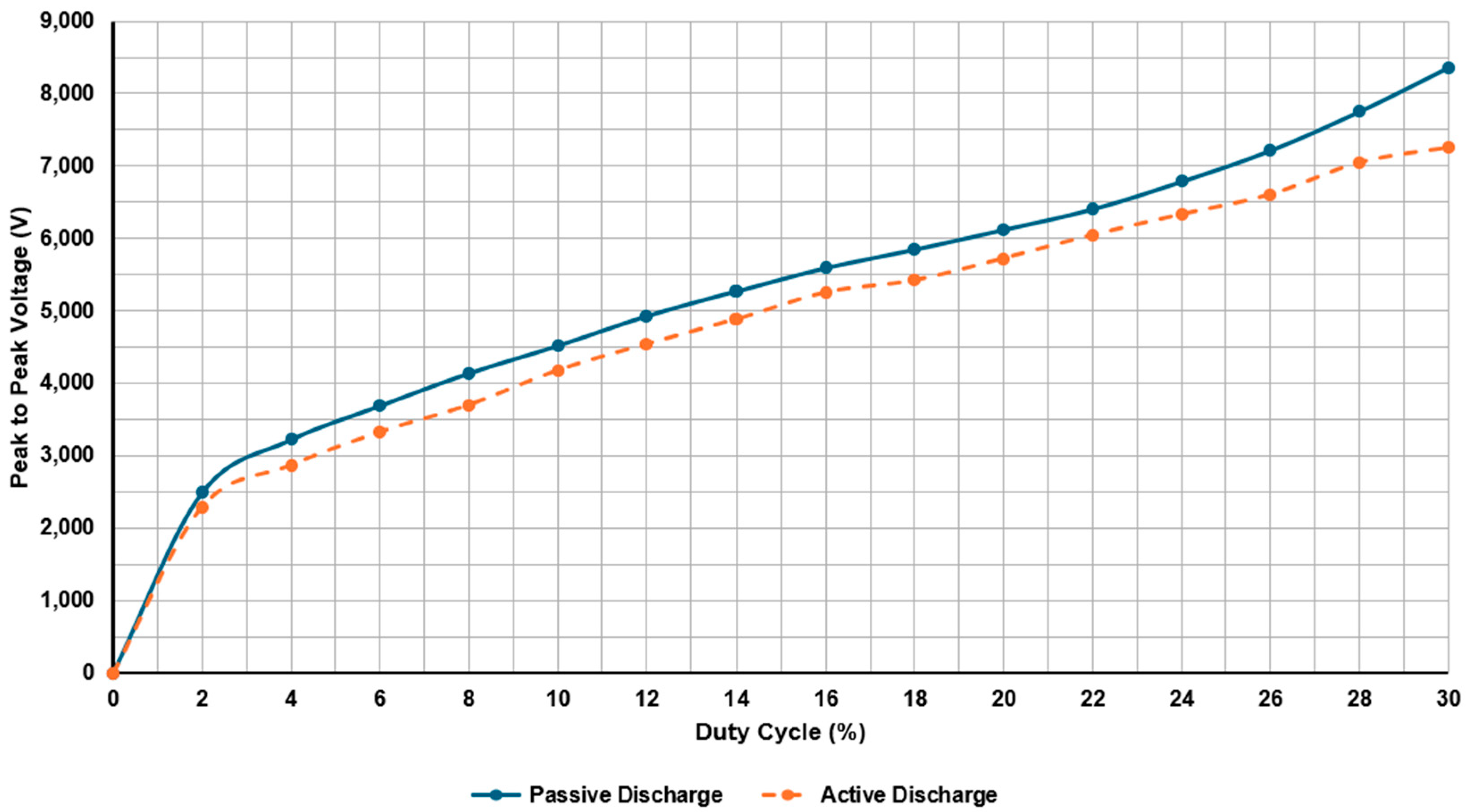

3.2.2. Negative HVDC Output

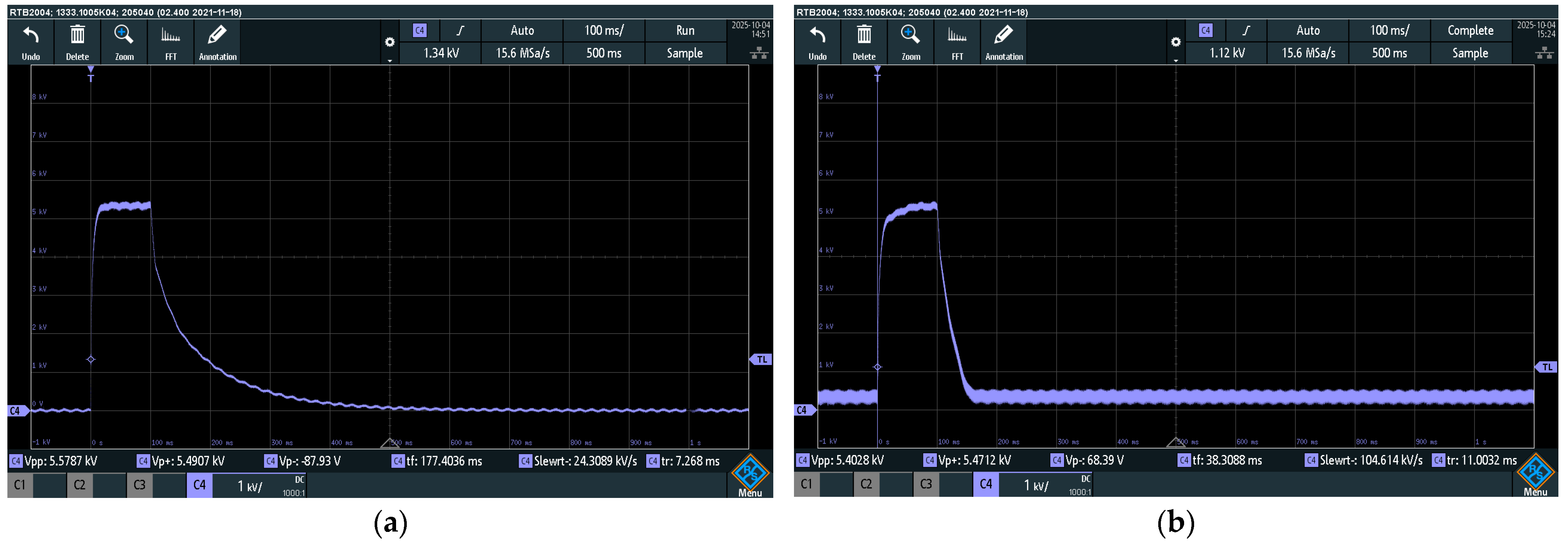

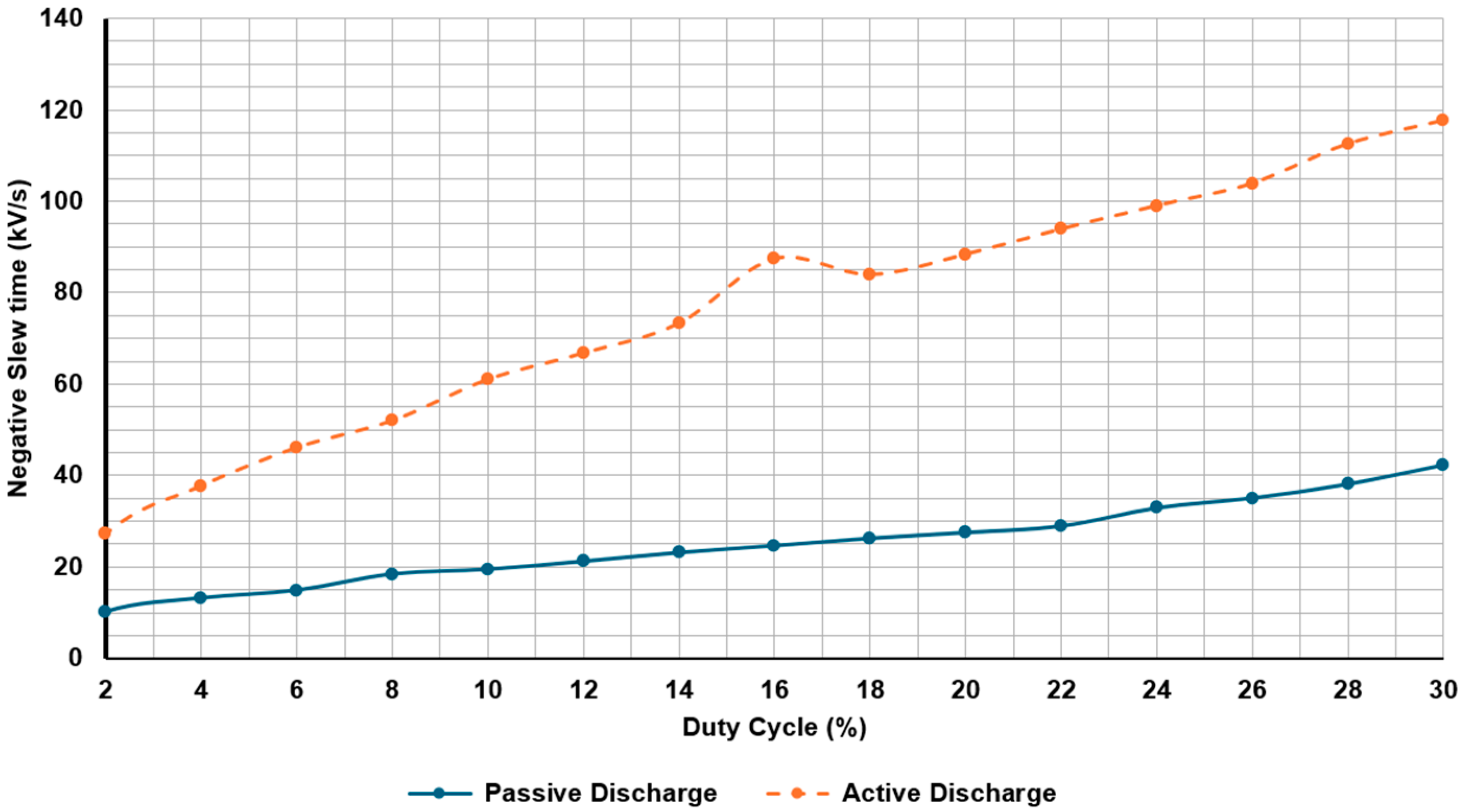

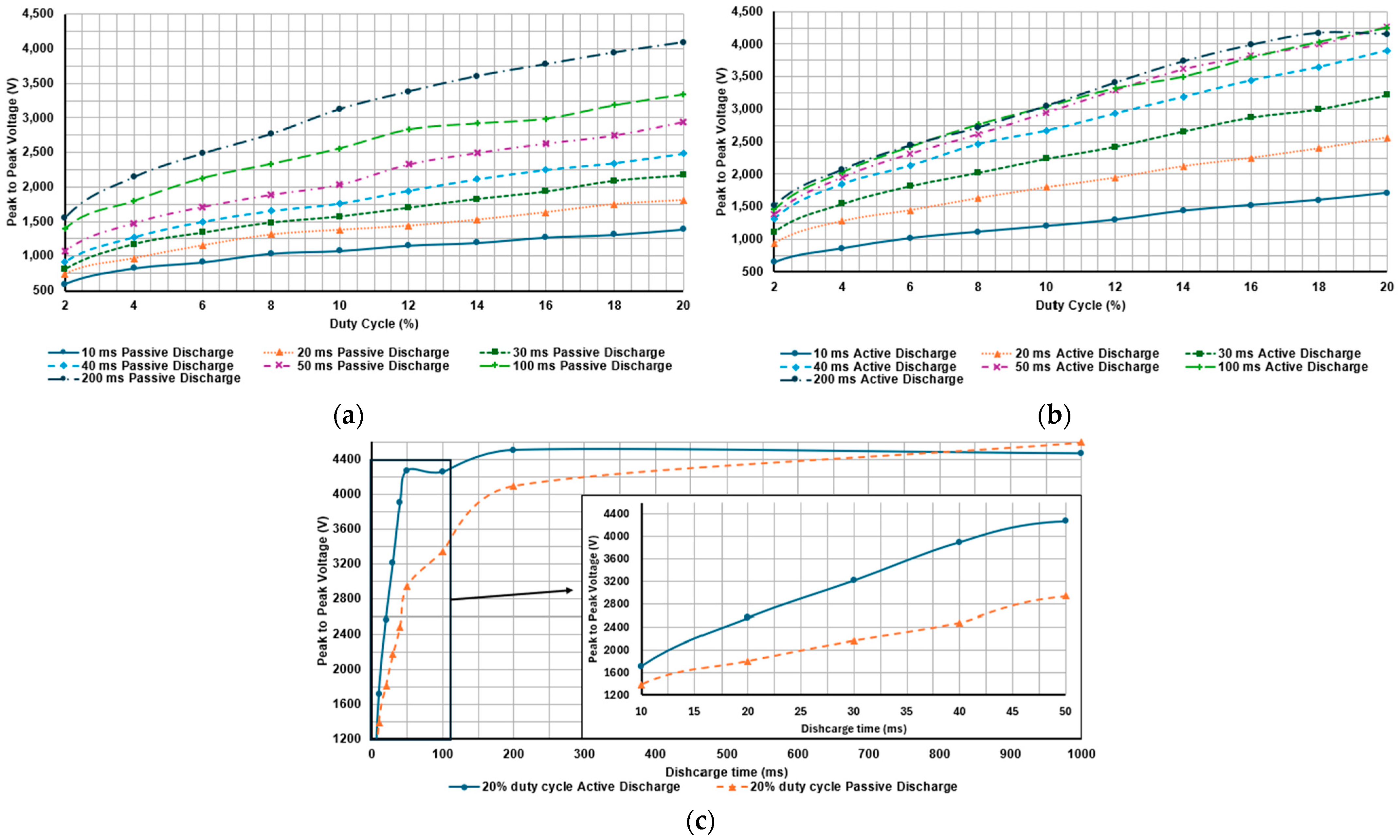

3.2.3. Discharge Recovery Time

3.2.4. HASEL Performance with the Low-Cost HVPS

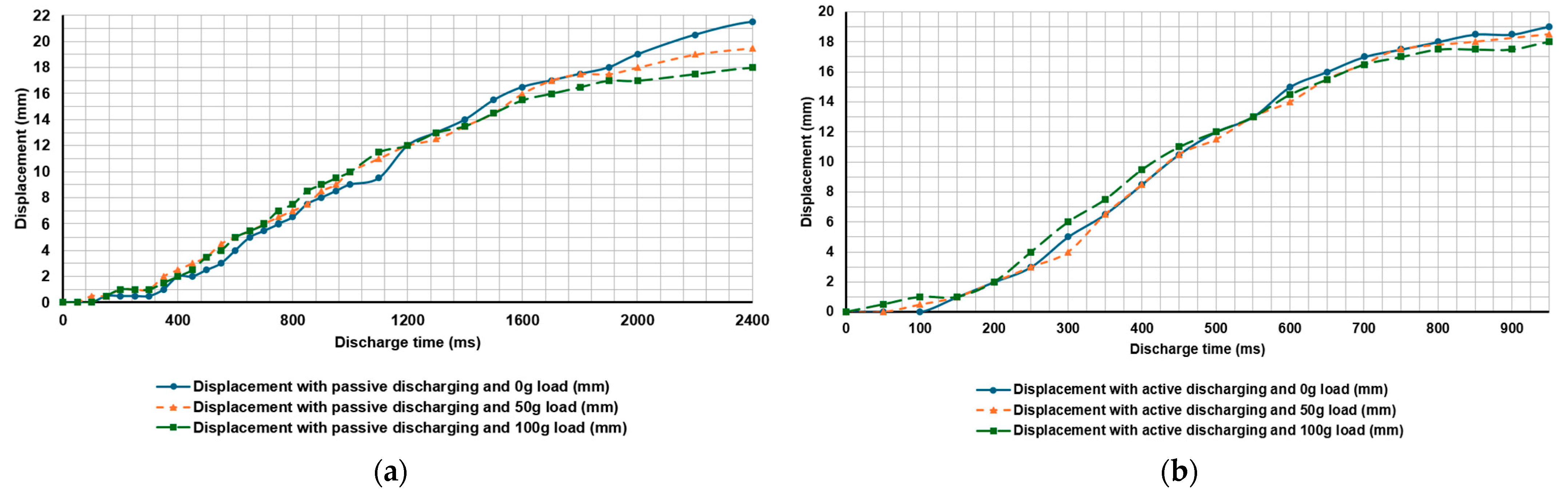

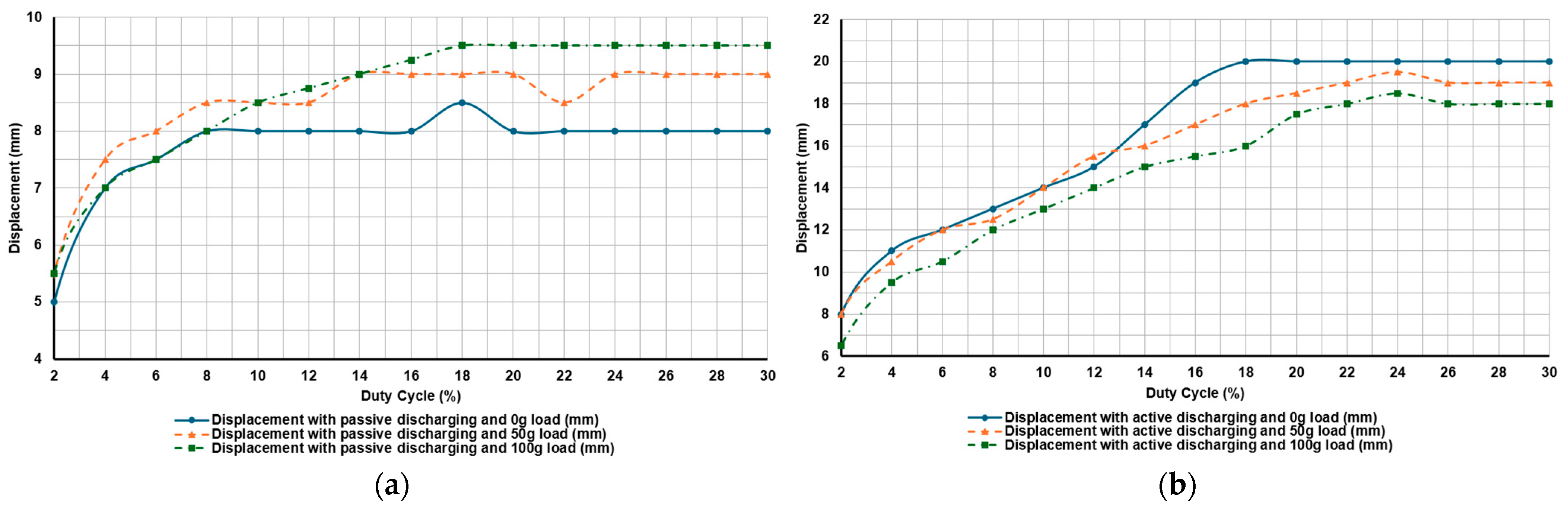

HASEL Displacement Results

HASEL Recovery Time

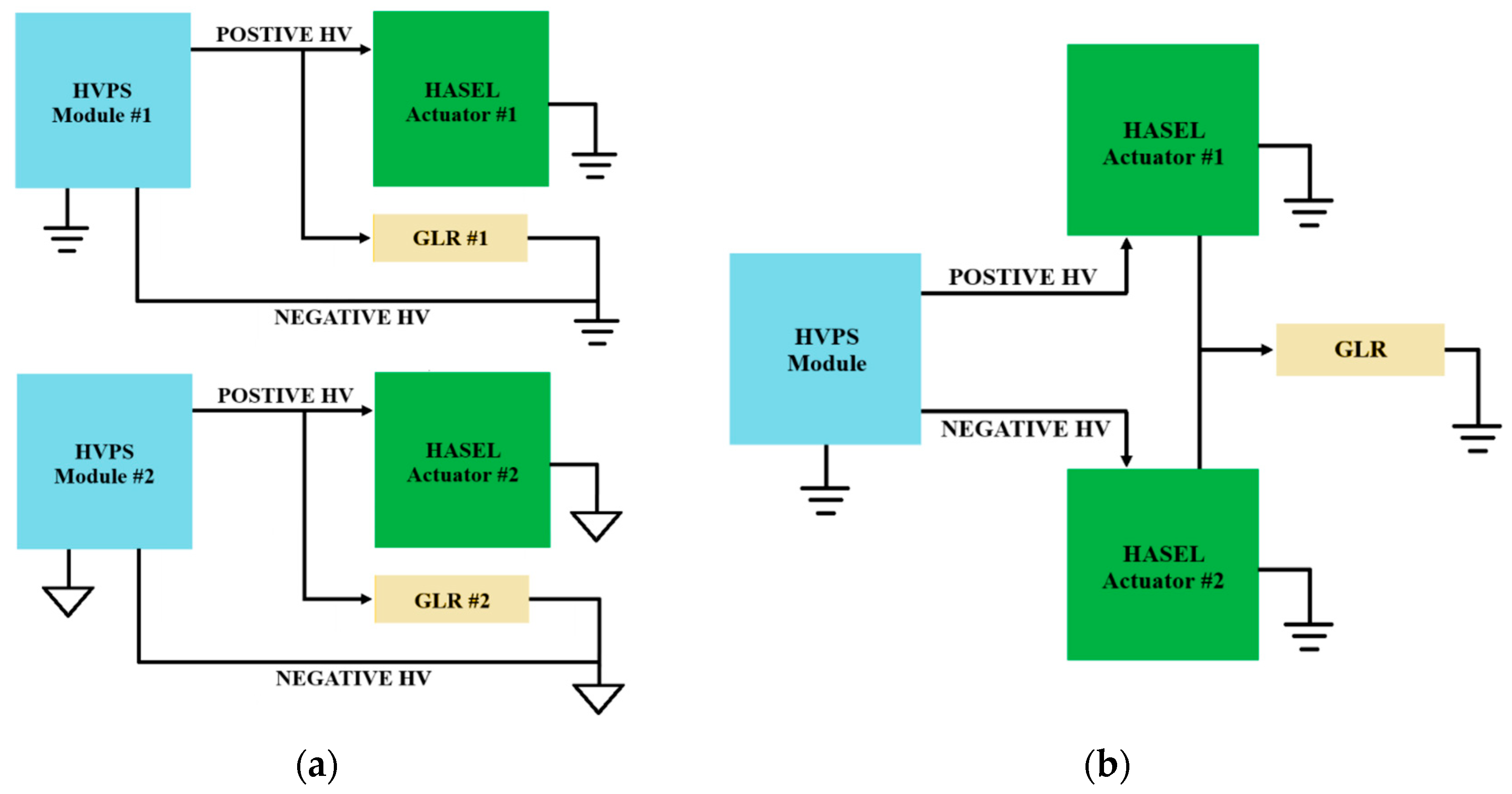

3.2.5. Operation Modes—Multi-Channel Operation

4. Discussion

4.1. Passive and Active Discharge Comparison—No Load

4.2. Passive and Active Discharge Comparison with the HASEL Actuator

4.3. Low-Cost Multi-Channel HVPS Specifications

4.4. Disadvantages of the Low-Cost HVPS

4.5. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acome, E.; Mitchell, S.K.; Morrissey, T.G.; Emmett, M.B.; Benjamin, C.; King, M.; Radakovitz, M.; Keplinger, C. Hydraulically amplified self-healing electrostatic actuators with muscle-like performance. Science 2018, 359, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellaris, N.; Gopaluni Venkata, V.; Smith, G.M.; Mitchell, S.K.; Keplinger, C. Peano-HASEL actuators: Muscle-mimetic, electrohydraulic transducers that linearly contract on activation. Sci. Robot. 2018, 3, eaar3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothemund, P.; Kellaris, N.; Mitchell, S.K.; Acome, E.; Keplinger, C. Hasel Actuators: HASEL Artificial Muscles for a New Generation of Lifelike Robots—Recent Progress and Future Opportunities. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2170149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.K.; Wang, X.; Acome, E.; Martin, T.; Ly, K.; Kellaris, N.; Venkata, V.G.; Keplinger, C. An Easy-to-Implement Toolkit to Create Versatile and High-Performance HASEL Actuators for Untethered Soft Robots. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1900178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellaris, N.; Rothemund, P.; Zeng, Y.; Mitchell, S.K.; Smith, G.M.; Jayaram, K.; Keplinger, C. Spider-Inspired Electrohydraulic Actuators for Fast, Soft-Actuated Joints. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2100916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ion-Dan, S.; Giacomo, M.; Sandra, D.; Luca, F.; Rocco, V.; Devid, M.; Marco, F. Electrostatic actuator for tactile display based on hydraulically coupled dielectric fluids and soft structures. In Proceedings of the SPIE, Denver, CO, USA, 19 March 2019; p. 109662D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sîrbu, I.D.; Moretti, G.; Bortolotti, G.; Bolignari, M.; Diré, S.; Fambri, L.; Vertechy, R.; Fontana, M. Electrostatic bellow muscle actuators and energy harvesters that stack up. Sci. Robot. 2021, 6, eaaz5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frediani, G.; Busfield, J.; Carpi, F. Enabling portable multiple-line refreshable Braille displays with electroactive elastomers. Med. Eng. Phys. 2018, 60, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, E.; Shea, H. Hydraulically Amplified Electrostatic Taxels (HAXELs) for Full Body Haptics. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2300242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, E.; Hinchet, R.; Shea, H. Multimode Hydraulically Amplified Electrostatic Actuators for Wearable Haptics. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2002564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, E.; Shea, H.; Gao, M. Hydraulically Amplified Dielectric Actuator Taxels. 2022. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US11372481B2/en (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Sanchez-Tamayo, N.; Yoder, Z.; Rothemund, P.; Ballardini, G.; Keplinger, C.; Kuchenbecker, K.J. Cutaneous Electrohydraulic (CUTE) Wearable Devices for Pleasant Broad-Bandwidth Haptic Cues. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2402461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Mitchell, S.K.; Rumley, E.H.; Rothemund, P.; Keplinger, C. High-Strain Peano-HASEL Actuators. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1908821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlatter, S.; Grasso, G.; Rosset, S.; Shea, H. Inkjet Printing of Complex Soft Machines with Densely Integrated Electrostatic Actuators. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2020, 2, 2000136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diteesawat, R.S.; Helps, T.; Taghavi, M.; Rossiter, J. Electro-pneumatic pumps for soft robotics. Sci. Robot. 2021, 6, eabc3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, T.J.K.; Fukushima, T.; Kazemipour, A.; Gravert, S.-D.; Prairie, M.; Romanescu, P.; Arm, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.L.; et al. Electrohydraulic musculoskeletal robotic leg for agile, adaptive, yet energy-efficient locomotion. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Yuan, Z.; Guo, J.; Bai, L.; Zhu, X.; Liu, F.; Pu, H.; Xin, L.; Peng, Y.; Luo, J.; et al. Legless soft robots capable of rapid, continuous, and steered jumping. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Kim, S.; Cha, Y. Soft origami tripod based on electrohydraulic actuator for multimodal motions. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 372, 115334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynan, L.; Gunawardana, U.; Liyanapathirana, R.; Perera, O.; Esposito, D.; Centracchio, J.; Gargiulo, G. Review of Electrohydraulic Actuators Inspired by the HASEL Actuator. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynan, L.; Gunawardana, U.; Liyanapathirana, R.; Perera, O.; Esposito, D.; Centracchio, J.; Gargiulo, G. Low-Cost High-Voltage Power Supply for Hydraulically Amplified Self-Healing Electrostatic Applications. Machines 2024, 12, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, M.; Helps, T.; Rossiter, J. Characterisation of Self-locking High-contraction Electro-ribbon Actuators. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 5856–5861. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder, Z.; Rumley, E.H.; Schmidt, I.; Rothemund, P.; Keplinger, C. Hexagonal electrohydraulic modules for rapidly reconfigurable high-speed robots. Sci. Robot. 2024, 9, eadl3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravert, S.-D.; Varini, E.; Kazemipour, A.; Michelis, M.Y.; Buchner, T.; Hinchet, R.; Katzschmann, R.K. Low-voltage electrohydraulic actuators for untethered robotics. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadi9319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Yang, M.; Fan, P.; Lu, T.; Wang, T. A new flexible electrostatic generator using dielectric fluid. J. Appl. Phys. 2023, 134, 105001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, Z.; Kellaris, N.; Chase-Markopoulou, C.; Ricken, D.; Mitchell, S.K.; Emmett, M.B.; Weir, R.F.F.; Segil, J.; Keplinger, C. Design of a High-Speed Prosthetic Finger Driven by Peano-HASEL Actuators. Front. Robot. AI 2020, 7, 586216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranti, M.; Righi, M.; Vertechy, R.; Fontana, M. A new class of variable capacitance generators based on the dielectric fluid transducer. Smart Mater. Struct. 2017, 26, 115014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlatter, S.; Illenberger, P.; Rosset, S. Peta-pico-Voltron: An open-source high voltage power supply. HardwareX 2018, 4, e00039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brei, Z.; Lim, C.W.; Ferguson, A.; Pradhan, A.A.; Sangeetha, V.V.; Bu, X.; Usui, B.; Johnson, D.B.; Vasudevan, R.; Moore, T.Y. HASEL Actuator Design for Out-of-Plane Bending: A Parametric Study of Planar Geometry. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft), San Diego, CA, USA, 14–17 April 2024; pp. 657–662. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, S.K.; Martin, T.; Keplinger, C. A Pocket-Sized Ten-Channel High Voltage Power Supply for Soft Electrostatic Actuators. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2022, 7, 2101469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manion, C.; Patel, D.; Fuge, M.; Bergbreiter, S. Modeling and Evaluation of Additive Manufactured HASEL Actuators. International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IEEE/RSJ), Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B.K.; Naris, M.; Sundaram, V.; Volchko, A.; Ly, K.; Mitchell, S.K.; Acome, E.; Kellaris, N.; Keplinger, C.; Correll, N.; et al. A multifunctional soft robotic shape display with high-speed actuation, sensing, and control. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, K.; Mayekar, J.V.; Aguasvivas, S.; Keplinger, C.; Rentschler, M.E.; Correll, N. Electro-Hydraulic Rolling Soft Wheel: Design, Hybrid Dynamic Modeling, and Model Predictive Control. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2022, 38, 3044–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robotics, A. Artimus Robotics. Available online: https://www.artimusrobotics.com/contracting-actuators (accessed on 15 August 2025).

| HV Components | Supplier | Unit Cost | Quantity Required | Total Cost AUD | Total Cost USD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 NF 10 KV HV Capacitors | AliExpress | AUD 0.236 | 8 | AUD 1.88 | USD 1.23 | ||

| 5 mA 20 kV HV Diode | AliExpress | AUD 0.39 | 8 | AUD 3.12 | USD 2.05 | ||

| Coil Arc Generator Step-up Boost Converter Power Transformer | AliExpress | AUD 0.64 | 2 | AUD 1.28 | USD 0.84 | ||

| Subtotal | AUD 6.28 | USD 4.12 | |||||

| LVComponents | Supplier | Part No. | Unit Cost | Quantity Required | Total Cost AUD | Total Cost USD | |

| DRV8841 Dual H-Bridge Driver IC | Texas Instruments | DRV8841P | AUD 2.705 | 1 | AUD 2.71 | USD 1.78 | |

| LM555 Timer | Texas Instruments | LM555CM | AUD 1.018 | 1 | AUD 1.02 | USD 0.67 | |

| Electrolytic Capacitor 470 UF 25 V | Mouser | EEE-FK1E471P | AUD 0.799 | 1 | AUD 0.80 | USD 0.52 | |

| Electrolytic Capacitor 220 UF 25 V | Mouser | EEE-1EA221UP | AUD 0.584 | 1 | AUD 0.54 | USD 0.35 | |

| Power Inductors | Mouser | 7447709221 | AUD 3.090 | 1 | AUD 3.09 | USD 2.03 | |

| Diodes 400 mW 100 Vrrm | Mouser | 1N4148W-13-F | AUD 0.126 | 1 | AUD 0.13 | USD 0.09 | |

| Schottky Diodes 2.0 Amp 40 V | Mouser | SSA24-E3/61T | AUD 0.436 | 1 | AUD 0.44 | USD 0.29 | |

| N-Ch MOSFET 60 Volt 35 Amp | Mouser | STD30NF06LT4 | AUD 1.960 | 1 | AUD 1.96 | USD 1.28 | |

| Trimmer Resistors | Mouser | 3361P-1-103GLF | AUD 1.480 | 1 | AUD 1.48 | USD 0.97 | |

| Ceramic Capacitor 100 V 100 pF | Mouser | C1206C101F1GAC TU | AUD 0.711 | 4 | AUD 2.84 | USD 1.86 | |

| 10 k Resistors 1/4 W | Mouser | CRCW120610K0JN EB | AUD 0.042 | 2 | AUD 0.08 | USD 0.05 | |

| FireBeetle ESP32 IOT Mi- crocontroller (Supports Wi-Fi and Bluetooth) | Core Electronics | AUD 17.80 | 1 | AUD 17.80 | USD 11.67 | ||

| Subtotal | AUD 32.45 | USD 21.27 | |||||

| Additional | Supplier | Purchase Cost | Quantity | Qty Re- quired | Qty Re- quired Cost | Total Cost AUD | Total Cost USD |

| 4-layer 66 × 111.8 FR-4 PCB | PCBWay | USD 100.14 * | 10 | 1 | USD 10.01 | AUD 15.26 | USD 10.01 |

| Potting Compound Silicone 1 kg PCT- 7000Y | Altronics | AUD 203.4 | 1 kg | 176 g | AUD 35.34 | AUD 35.34 | USD 23.17 |

| Subtotal | AUD 50.60 | USD 33.17 | |||||

| Total | AUD 83.05 * | USD 54.45 * | |||||

| LV Components | Supplier | Part No. | Unit Cost | Quantity Required | Total Cost AUD | Total Cost USD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrolytic Capacitor 470 UF 25 V | Mouser | EEE-FK1E471P | AUD 0.799 | 1 | AUD 0.80 | USD 0.52 | |

| N-Ch MOSFET 60 Volt 35 Amp | Mouser | STD30NF06LT4 | AUD 1.960 | 1 | AUD 1.96 | USD 1.28 | |

| Ceramic Capacitor 100 V 100 pF | Mouser | C1206C101F1GAC TU | AUD 0.711 | 4 | AUD 2.84 | USD 1.86 | |

| 10 k Resistors 1/4 W | Mouser | CRCW120610K0JN EB | AUD 0.042 | 2 | AUD 0.08 | USD 0.05 | |

| Gate Drivers DRIVER IC | Mouser | 1EDN8511BXUSA1 | AUD 0.615 | 2 | AUD 1.23 | USD 0.81 | |

| FireBeetle ESP32 IOT Mi- crocontroller (Supports Wi-Fi and Bluetooth) | Core Electronics | AUD 17.80 | 1 | AUD 17.80 | USD 11.67 | ||

| Subtotal | AUD 24.71 | USD 16.20 | |||||

| Additional | Supplier | Purchase Cost | Quantity | Qty Re- quired | Qty Re- quired Cost | Total Cost AUD | Total Cost USD |

| 4-layer 66 × 48.1 mm FR-4 PCB | PCBWay | USD 68.39 * | 20 | 1 | USD 3.42 | AUD 5.21 | USD 3.42 |

| Potting Compound Silicone 1 kg PCT- 7000Y | Altronics | AUD 203.4 | 1 kg | 61 g | AUD 12.4 | AUD 12.4 | USD 8.13 |

| Subtotal | AUD 17.61 | USD 11.55 | |||||

| Total | AUD 48.6 * | USD 31.86 * | |||||

| Passive Discharge Mode | Active Discharge Mode | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duty Cycle (%) | Rise Time (ms) | Fall Time (ms) | Rise Time (ms) | Fall Time (ms) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 17.995 | 166.308 | 29.734 | 34.160 |

| 4 | 18.934 | 175.407 | 23.377 | 37.113 |

| 6 | 20.709 | 172.758 | 34.426 | 37.959 |

| 8 | 18.934 | 182.086 | 33.368 | 39.652 |

| 10 | 18.354 | 179.308 | 31.022 | 41.464 |

| 12 | 17.811 | 176.41 | 27.720 | 41.409 |

| 14 | 15.493 | 176.64 | 29.817 | 40.066 |

| 16 | 16.045 | 175.564 | 26.330 | 40.25 |

| 18 | 16.201 | 175.637 | 27.517 | 39.505 |

| 20 | 16.247 | 174.726 | 26.082 | 38.907 |

| 22 | 16.146 | 175.987 | 31.906 | 38.760 |

| 24 | 15.64 | 175.702 | 30.654 | 38.162 |

| 26 | 13.598 | 178.084 | 27.122 | 38.327 |

| 28 | 12.604 | 178.977 | 24.214 | 38.014 |

| 30 | 10.957 | 176.171 | 20.571 | 37.113 |

| 32 | 10.01 | 170.688 | 20.507 | 36.708 |

| 34 | 9.255 | 176.143 | 38.005 | |

| 36 | 8.151 | 175.361 | 11.003 | 38.309 |

| 38 | 7.452 | 176.392 | ||

| 40 | 7.268 | 177.404 | ||

| Average | 14.390 | 175.767 | 26.787 | 38.549 |

| Passive Discharge Mode | Active Discharge Mode | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duty Cycle (%) | Fall Time (ms) | Rise Time (ms) | Fall Time (ms) | Rise Time (ms) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 21.960 | 182.316 | 27.214 | 62.376 |

| 4 | 19.053 | 178.37 | 24.970 | 56.221 |

| 6 | 18.501 | 178.71 | 26.80 | 53.038 |

| 8 | 20.663 | 166.686 | 26.514 | 51.695 |

| 10 | 20.516 | 170.918 | 28.658 | 50.664 |

| 12 | 19.964 | 171.47 | 27.158 | 49.974 |

| 14 | 19.154 | 170.117 | 25.751 | 49.459 |

| 16 | 17.158 | 168.737 | 24.306 | 48.53 |

| 18 | 15.907 | 166.87 | 22.558 | 48.778 |

| 20 | 15.41 | 166.741 | 19.90 | 48.254 |

| 22 | 15.309 | 166.759 | 18.961 | 47.914 |

| 24 | 15.548 | 157.642 | 19.053 | 47.812 |

| 26 | 15.060 | 155.379 | 20.406 | 47.730 |

| 28 | 15.852 | 153.290 | 20.452 | 47.058 |

| 30 | 15.272 | 146.298 | 22.5 | 46.405 |

| Average | 17.689 | 166.687 | 23.680 | 50.394 |

| Blocking Force (N) | Free Stroke (mm) | Length (mm) | Width (mm) | Height (mm) | Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18.5 | 6 | 150 | 60 | 1.5 | 11 |

| Passive Discharge Mode | Active Discharge Mode | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duty Cycle (%) | Maximum Positive Frequency (Hz) | Maximum Negative Frequency (Hz) | Maximum Positive Frequency (Hz) | Maximum Negative Frequency (Hz) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 5.426 | 4.895 | 15.651 | 11.162 |

| 4 | 5.146 | 5.065 | 16.532 | 12.317 |

| 6 | 5.169 | 5.071 | 13.815 | 12.525 |

| 8 | 4.975 | 5.338 | 13.695 | 12.786 |

| 10 | 5.059 | 5.224 | 13.796 | 12.607 |

| 12 | 5.149 | 5.224 | 14.466 | 12.965 |

| 14 | 5.205 | 5.283 | 14.310 | 13.296 |

| 16 | 5.219 | 5.379 | 15.019 | 13.729 |

| 18 | 5.213 | 5.471 | 14.920 | 14.018 |

| 20 | 5.236 | 5.490 | 15.387 | 14.673 |

| 22 | 5.205 | 5.492 | 14.151 | 14.953 |

| 24 | 5.226 | 5.774 | 14.532 | 14.955 |

| 26 | 5.217 | 5.867 | 15.279 | 14.677 |

| 28 | 5.220 | 5.912 | 16.070 | 14.813 |

| 30 | 5.344 | 6.189 | 17.336 | 14.513 |

| 32 | 5.534 | 17.478 | ||

| 34 | 5.394 | |||

| 36 | 5.449 | 20.279 | ||

| 38 | 5.439 | |||

| 40 | 5.415 | |||

| Average | 5.262 | 5.445 | 16.057 | 13.599 |

| Input Characteristics | Positive Output Characteristics | Negative Output Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage (VDC) | Maximum Current (A) | Continuous Current (A) | Voltage (VDC) | Maximum Current (mA) | Voltage (VDC) | Maximum Current (mA) |

| 3–6 * | 3 | 2 | 0–5578.7 ** | 3.23 | 0–8365.5 ** | 2.15 |

| Input Characteristics | Output Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage (VDC) | Maximum Current (A) | Continuous Current (A) | Voltage (VDC) | Maximum Current (mA) |

| 3–25 | 3 | 2 | 0–10,056 ** | 796 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tynan, L.; Gunawardana, U.; Esposito, D.; Centracchio, J.; Minucci, S.; Chiariello, A.G.; Gargiulo, G. HASEL Actuators Activated with a Multi-Channel Low-Cost High Voltage Power Supply. Actuators 2025, 14, 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120601

Tynan L, Gunawardana U, Esposito D, Centracchio J, Minucci S, Chiariello AG, Gargiulo G. HASEL Actuators Activated with a Multi-Channel Low-Cost High Voltage Power Supply. Actuators. 2025; 14(12):601. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120601

Chicago/Turabian StyleTynan, Levi, Upul Gunawardana, Daniele Esposito, Jessica Centracchio, Simone Minucci, Andrea Gaetano Chiariello, and Gaetano Gargiulo. 2025. "HASEL Actuators Activated with a Multi-Channel Low-Cost High Voltage Power Supply" Actuators 14, no. 12: 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120601

APA StyleTynan, L., Gunawardana, U., Esposito, D., Centracchio, J., Minucci, S., Chiariello, A. G., & Gargiulo, G. (2025). HASEL Actuators Activated with a Multi-Channel Low-Cost High Voltage Power Supply. Actuators, 14(12), 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120601