Route-Preview Adaptive Model Predictive Motion Cueing for Driving Simulators

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

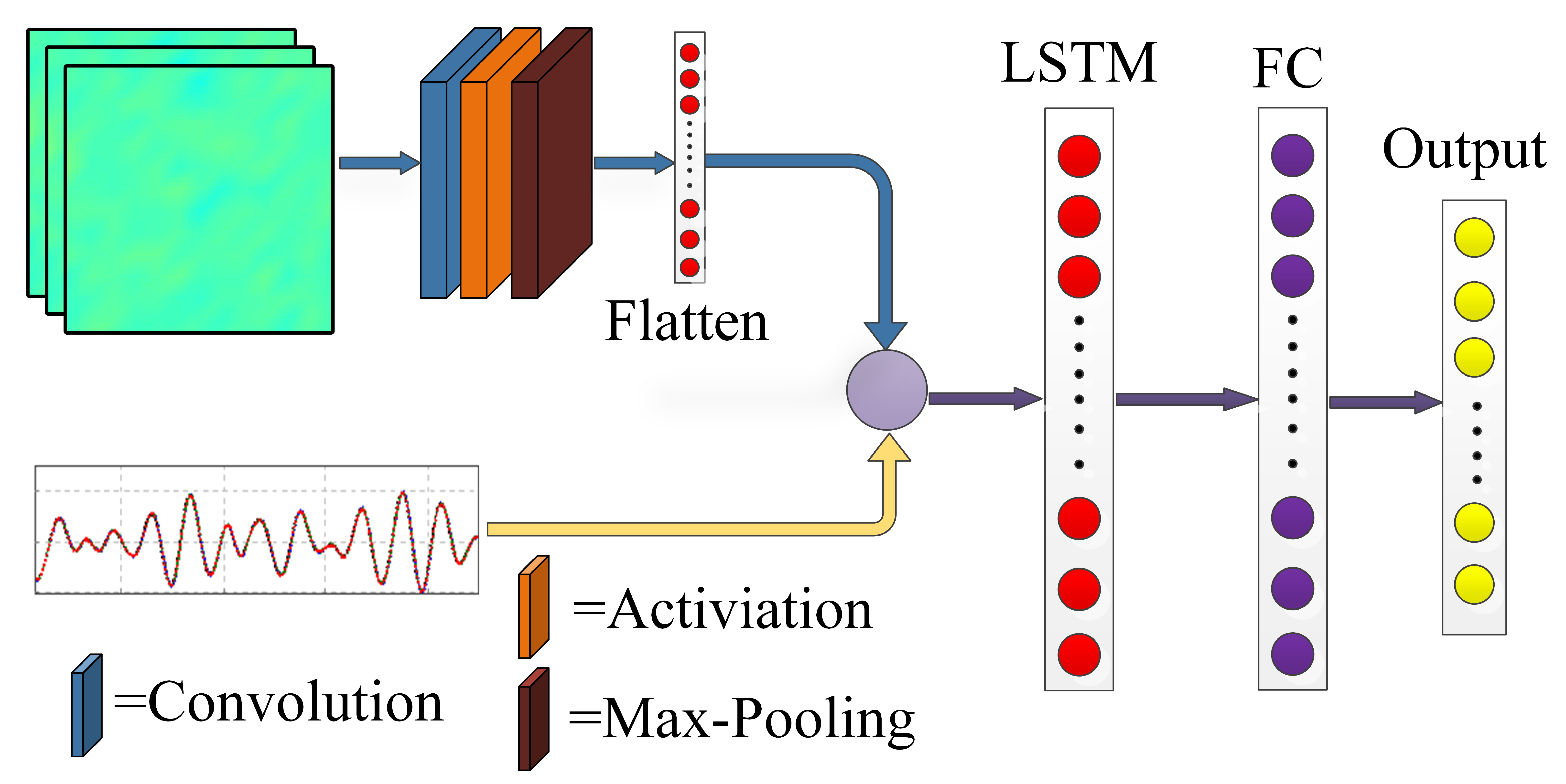

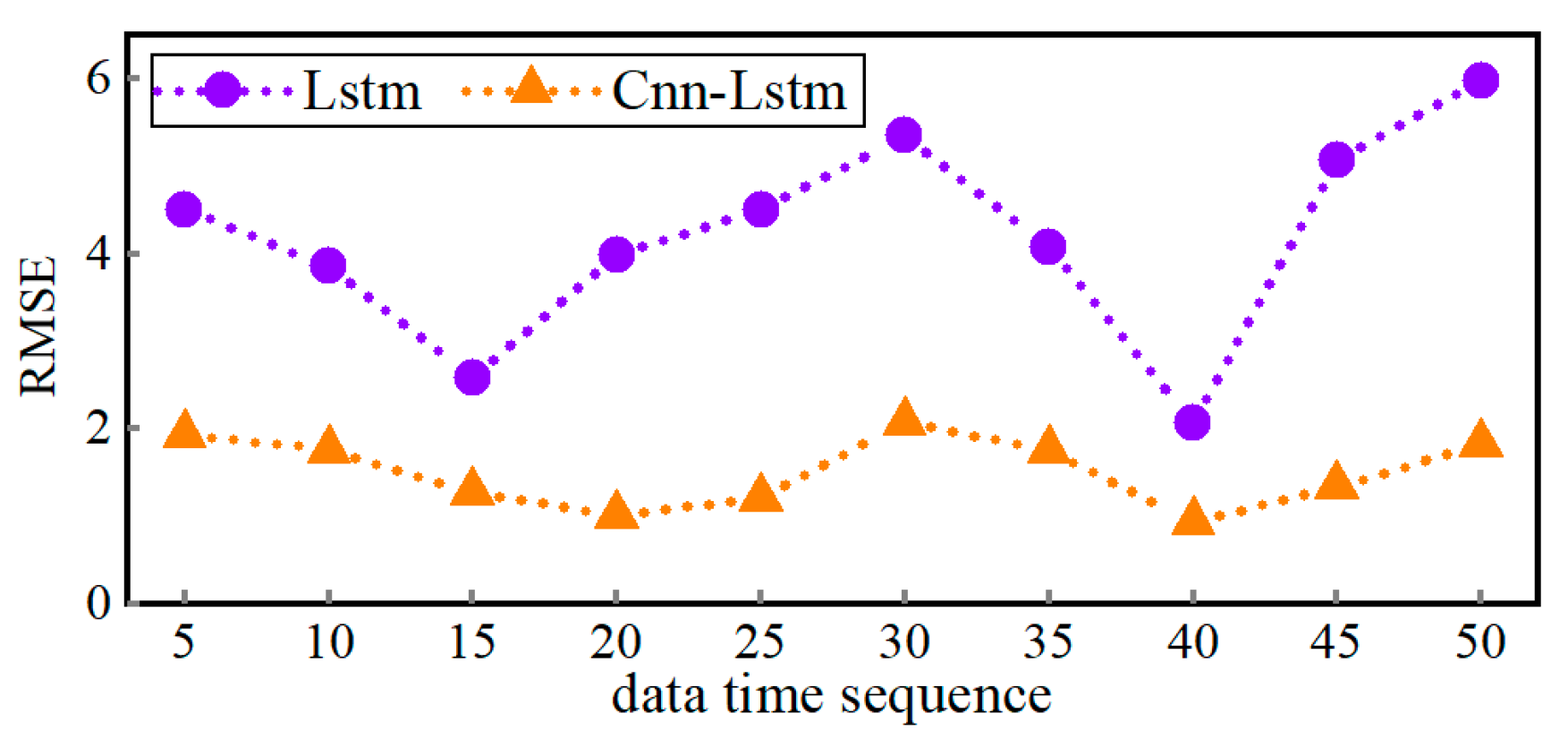

- A route-preview vehicle trajectory prediction framework is presented, in which forward terrain elevation maps are utilized as inputs to a CNN–LSTM deep network. By learning the nonlinear interactions among terrain features, vehicle dynamics, and driver operations, the network enables short-horizon prediction of future vehicle attitudes and accelerations under highly irregular road conditions.

- (2)

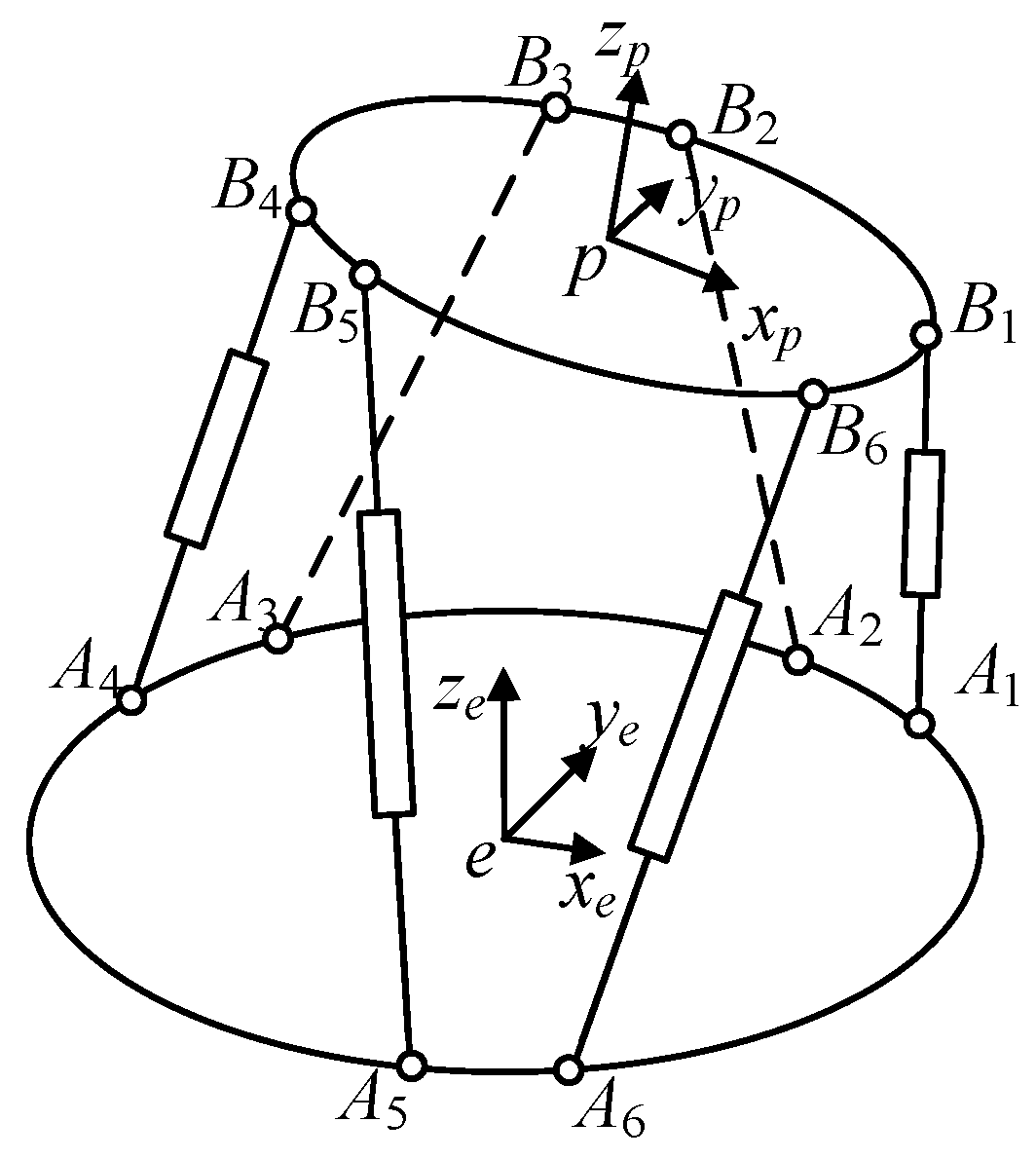

- A motion cueing prediction model is formulated, within which actuator stroke and velocity states are explicitly incorporated. Through the introduction of a dynamics-based platform model and the embedding of actuator stroke and velocity constraints into the prediction process, the physical feasibility of both reference trajectories and control solutions is ensured, thus addressing a key limitation of traditional MCA approaches that neglect actuator-level physical constraints.

- (3)

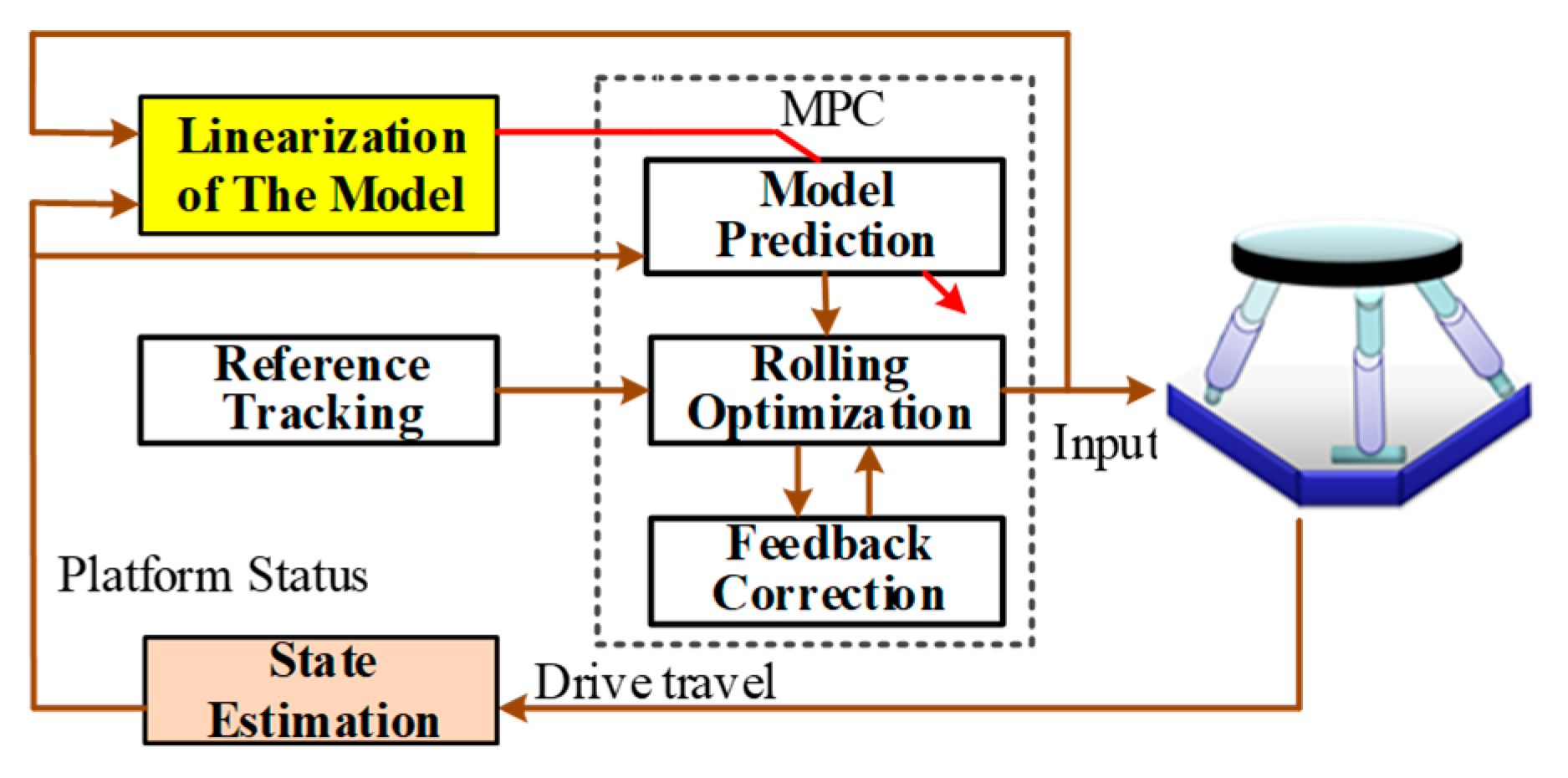

- An AMPC motion cueing algorithm integrated with EKF-based state estimation is developed, whereby real-time, filtered platform states are provided to enhance the consistency between the predictive model and the actual system dynamics. This integration enables a closed-loop prediction–estimation–optimization structure, leading to improved robustness and tracking performance under complex road excitations.

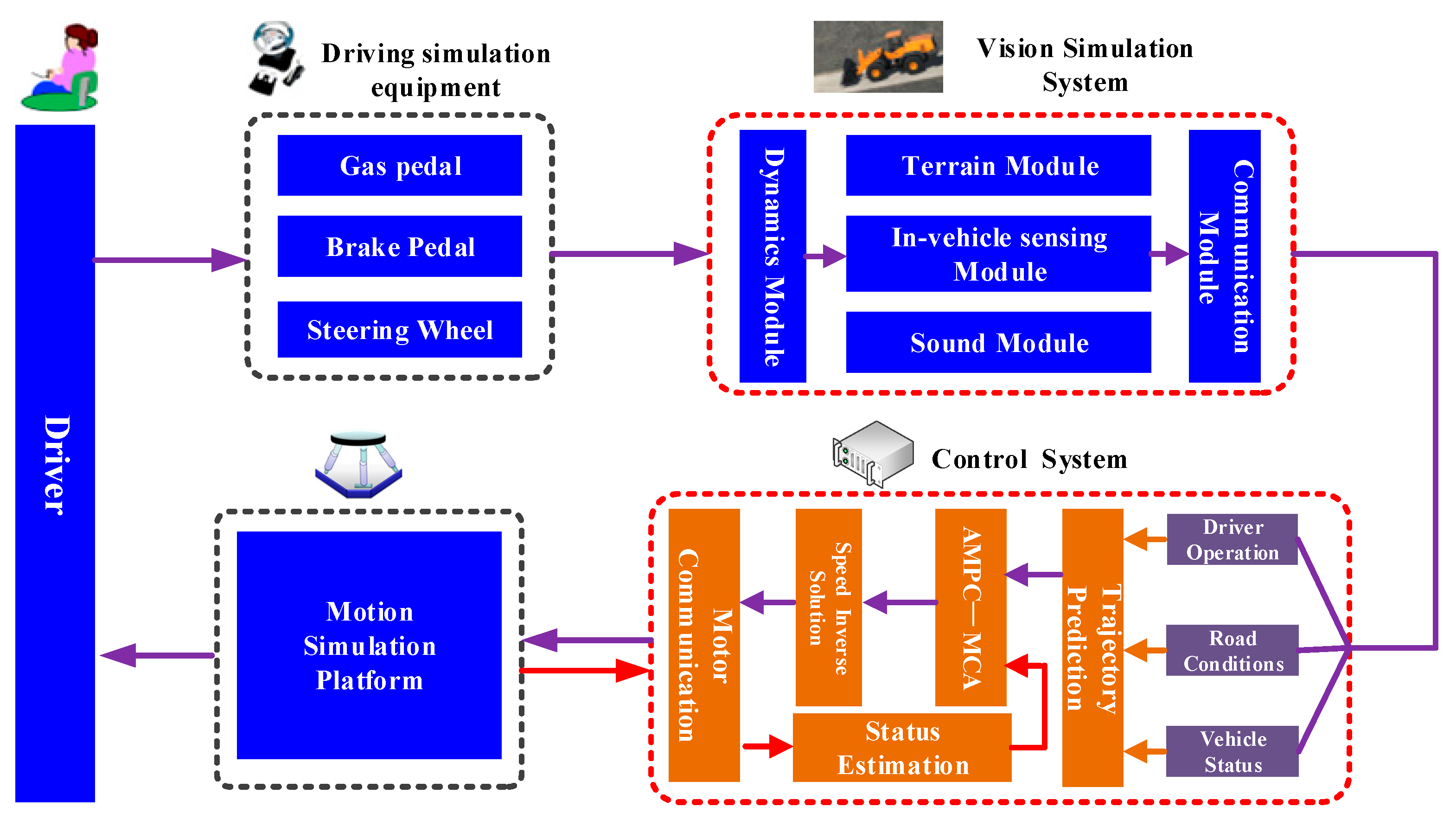

2. Vehicle Trajectory Prediction Model

2.1. Definition of Inputs and Outputs

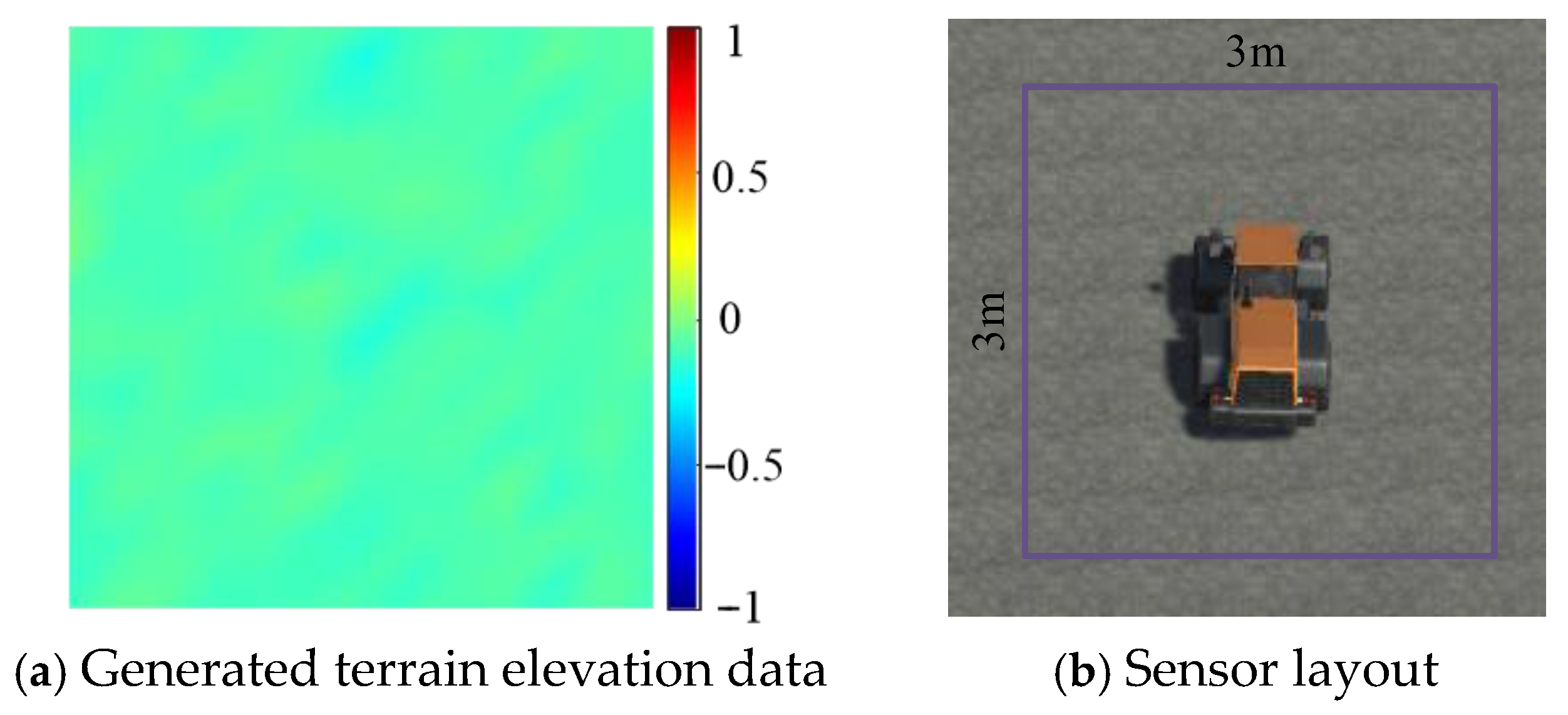

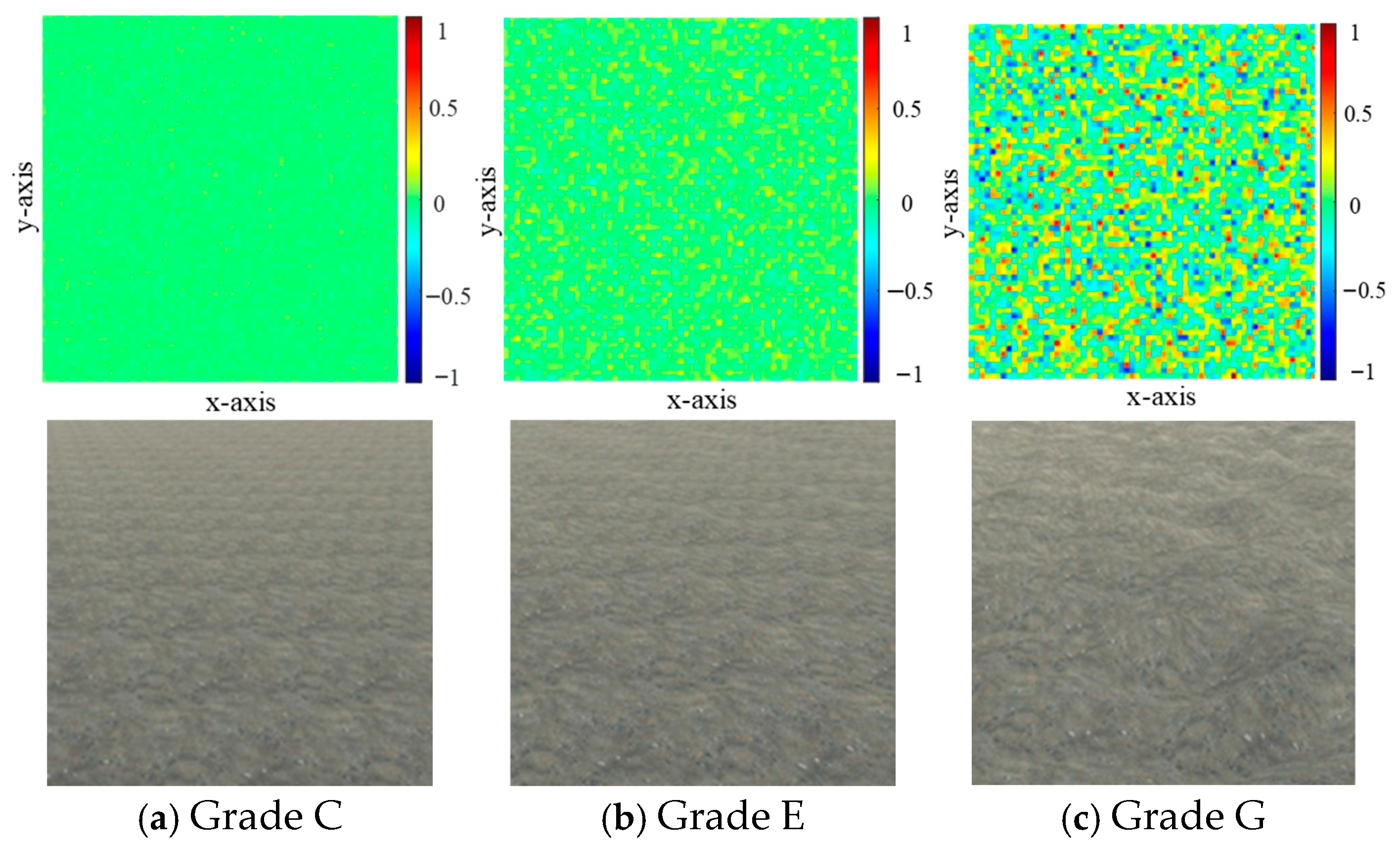

2.2. Driving Scenarios Creation

2.3. Architecture and Evaluation of Networks

3. AMPC-Based MCA

3.1. Motion Planning Model of the Platform

3.1.1. Human Vestibular System Model

3.1.2. Motion Simulation Platform State Model

3.2. Adaptive Model Predictive Control

3.2.1. State Estimation

3.2.2. Model Predictive Control

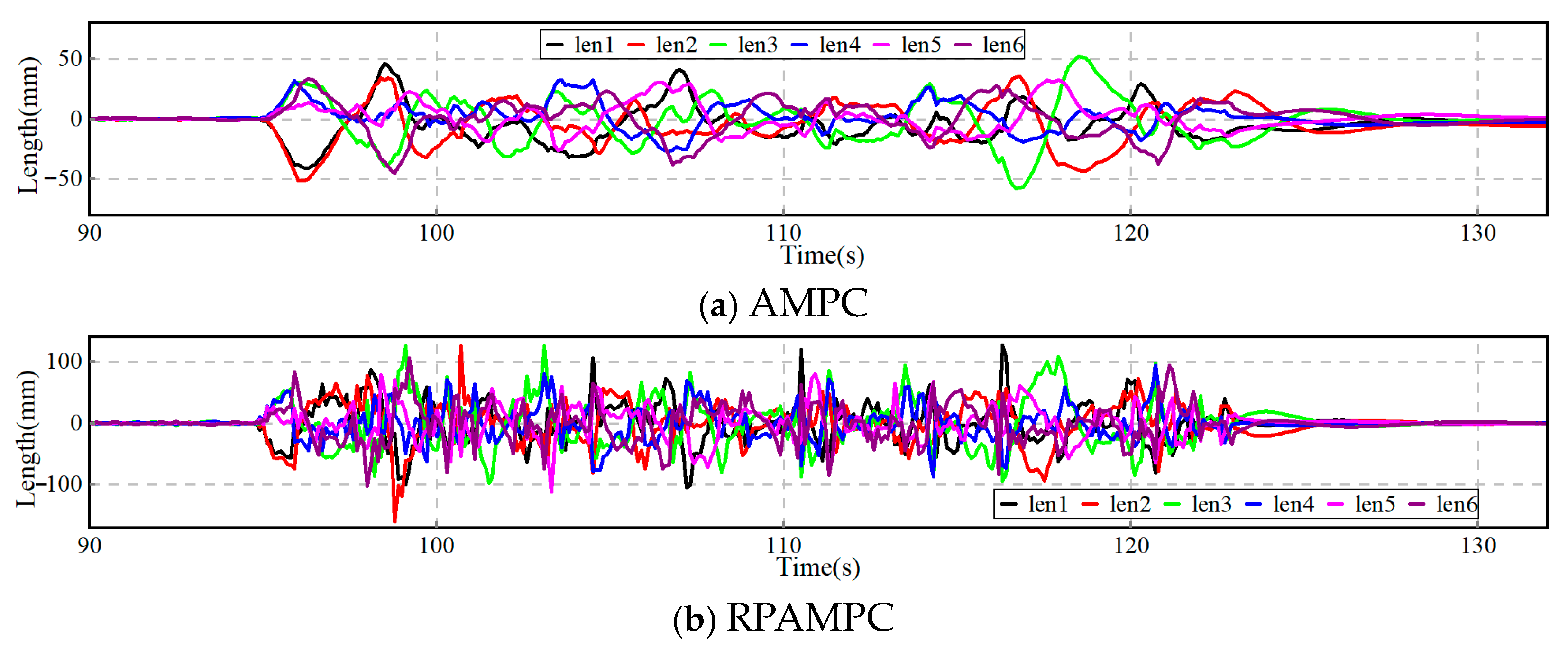

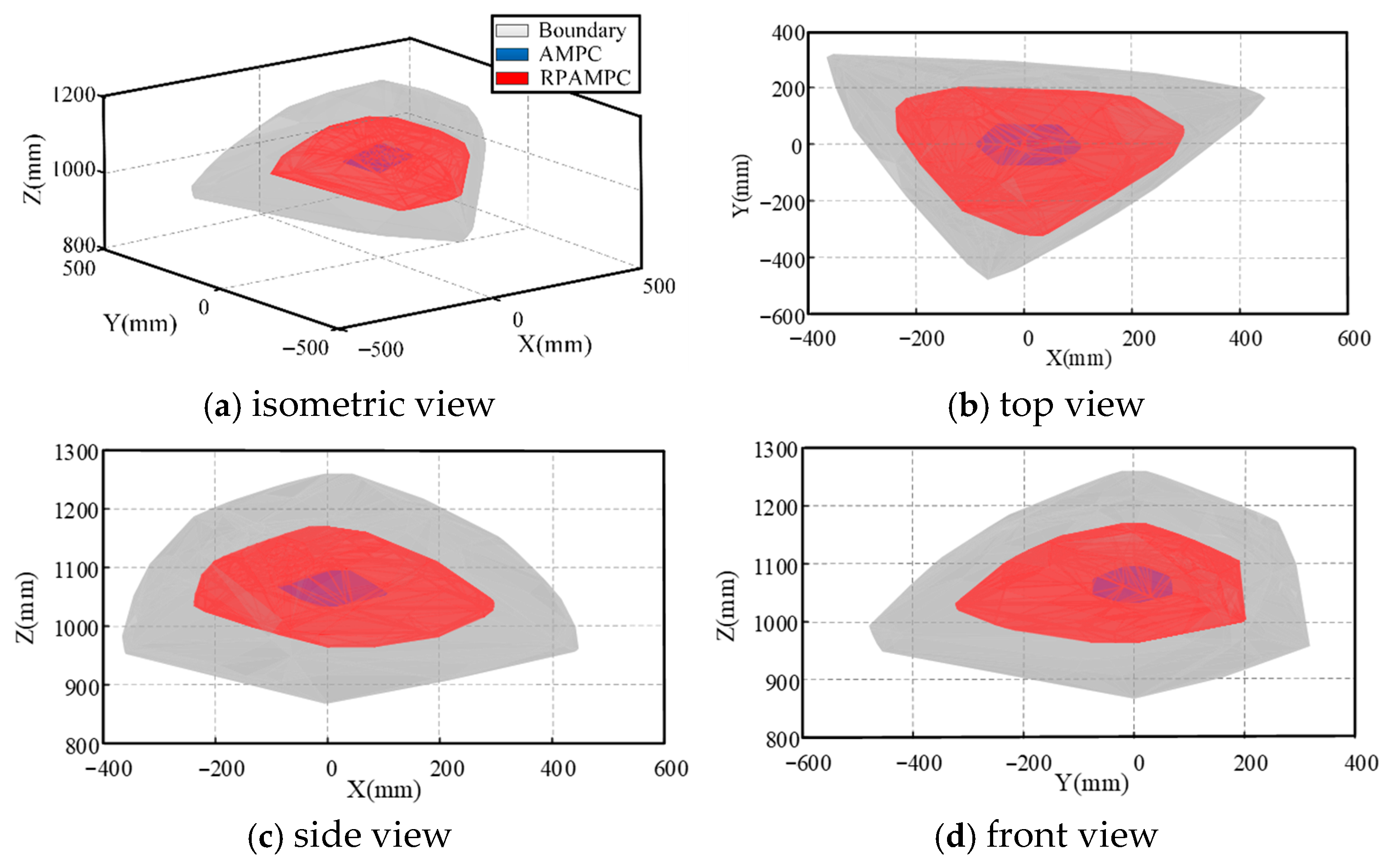

3.3. Objective Evaluation

4. Results and Discussions

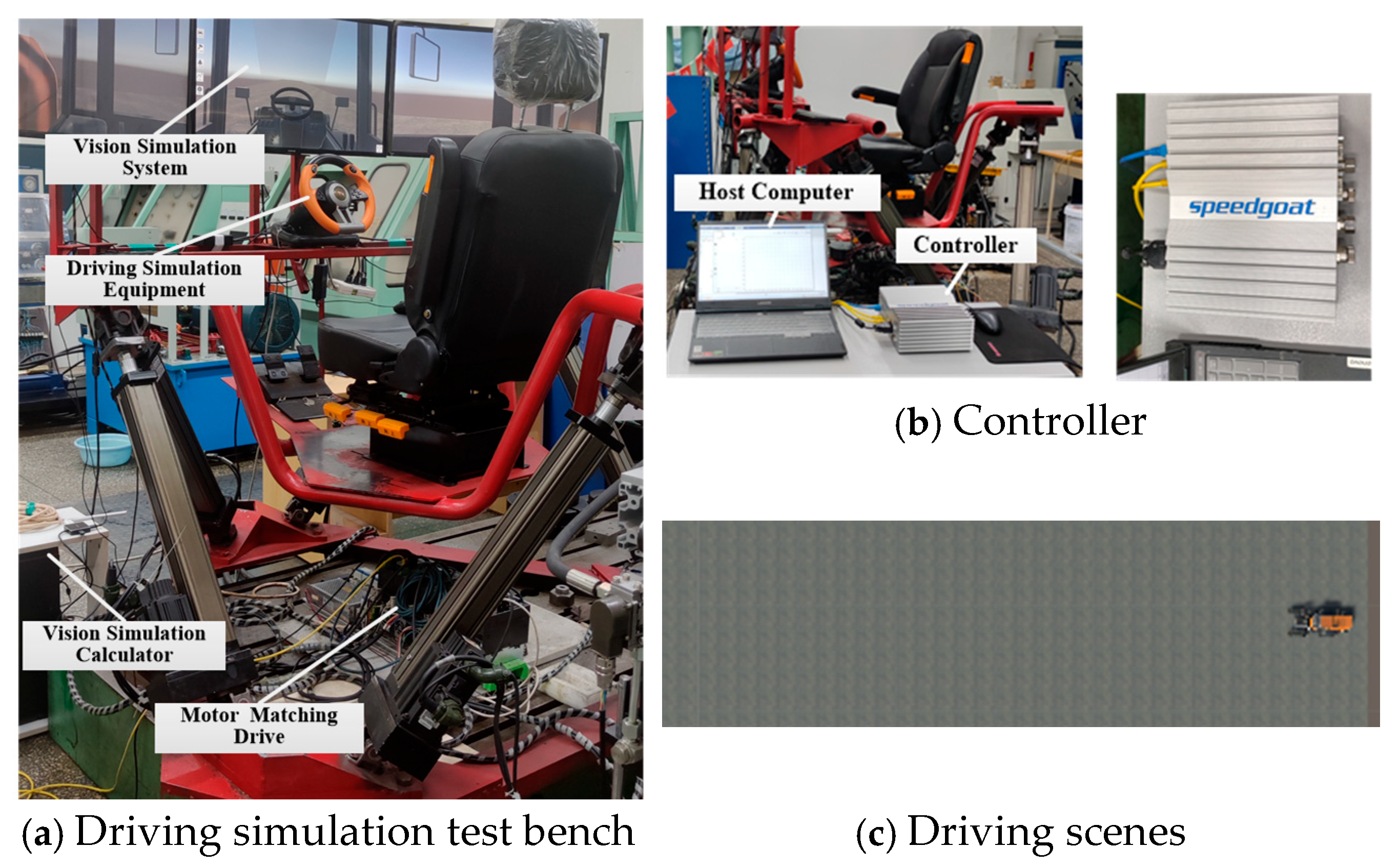

4.1. Design of the Experimental Scheme

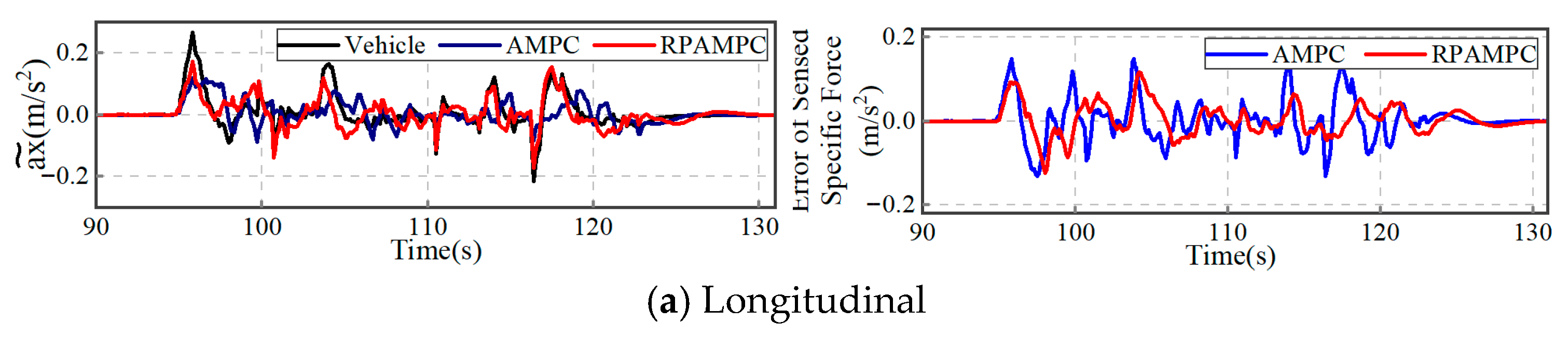

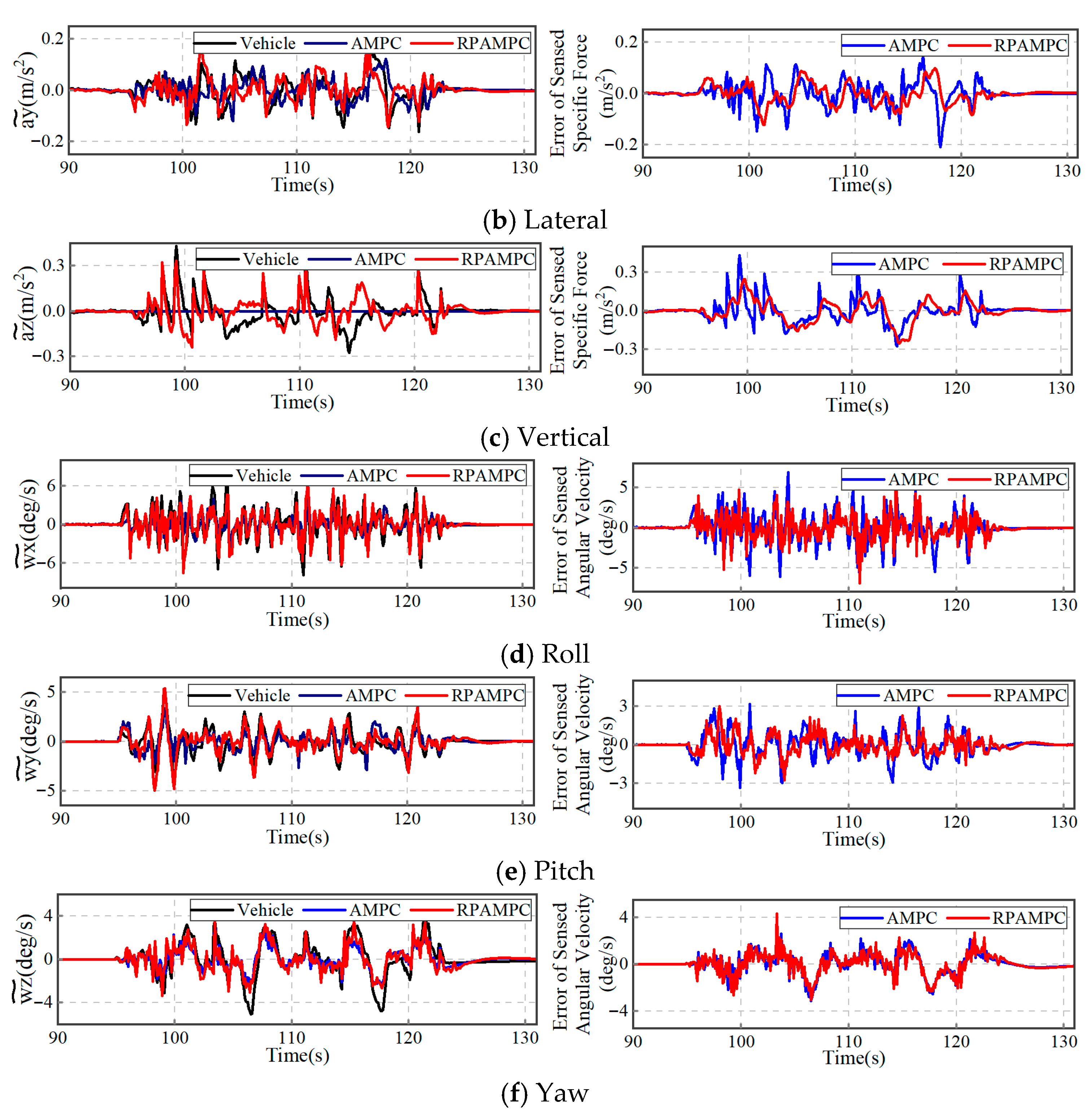

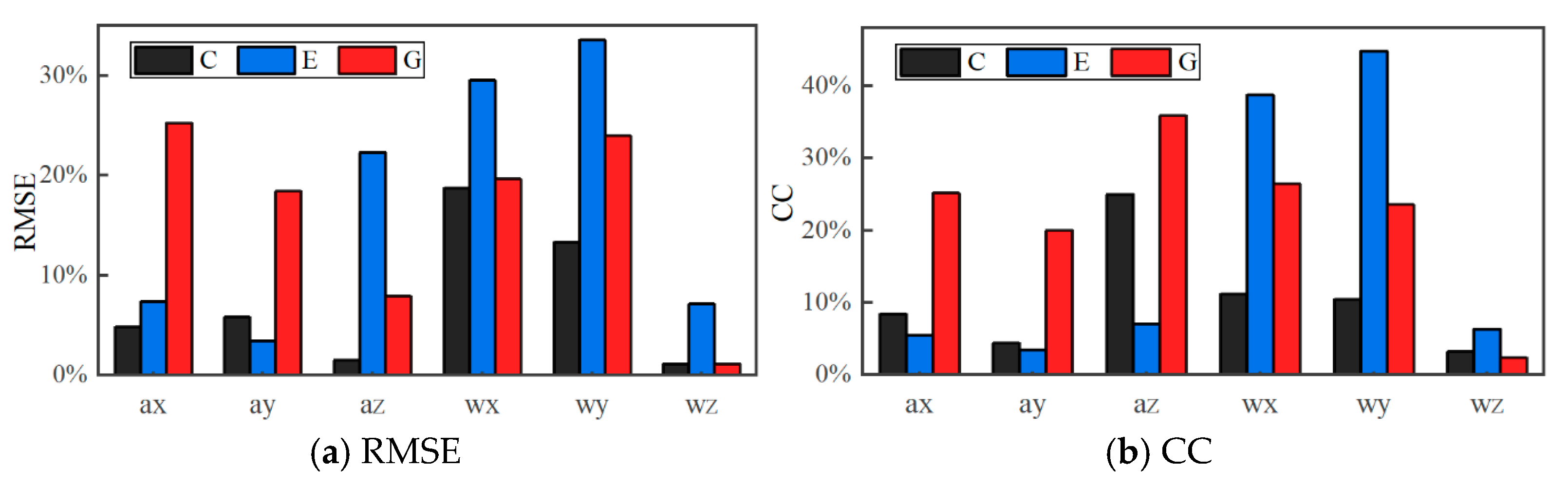

4.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olivari, M.; Pretto, P.; Venrooij, J.; Bülthoff, H. Defining the kinematic requirements for a theoretical driving simulator. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 61, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Chen, X.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, L. Objective Evaluation of Motion Cueing Algorithms for Vehicle Driving Simulator Based on Criteria Importance through Intercriteria Correlation (CRITIC) Weight Method Combined with Gray Correlation Analysis. Machines 2024, 12, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, S.-M.; Son, H.; Park, T. Effects of unlimited angular motion cue and cue discrepancy on simulator sickness. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 213, 119196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.-A.; Sauter, L.; Granrath, C.; Hadj-Amor, H.; Andert, J. Simulator Coupled with Distributed Co-Simulation Protocol for Automated Driving Tests. Automot. Innov. 2021, 4, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleij, D.; Venrooij, J.; Pretto, P.; Katliar, M.; Bülthoff, H.H.; Steffen, D.; Hoffmeyer, F.W.; Schöner, H.-P. Comparison between filter-and optimization-based motion cueing algorithms for driving simulation. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 61, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthoz, A.; Bles, W.; Bülthoff, H.H.; Grácio, B.C.; Feenstra, P.; Filliard, N.; Huhne, R.; Kemeny, A.; Mayrhofer, M.; Mulder, M.; et al. Motion scaling for high-performance driving simulators. IEEE Trans. Hum.-Mach. Syst. 2013, 43, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellensohn, F.; Venrooij, J.; Schwienbacher, M.; Rixen, D. Experimental evaluation of an optimization-based motion cueing algorithm. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 62, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.; Kumar, S.S.; Papaioannou, G.; Happee, R.; Shyrokau, B. Optimal trajectory planning for mitigated motion sickness: Simulator study assessment. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 10653–10664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschetta, M.; Cenedese, C.; Beghi, A. A real-time, MPC-based motion cueing algorithm with look-ahead and driver characterization. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 61, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, B.; Schmidt, S.F. A Study of Techniques for Calculating Motion Drive Signals for Flight Simulators; No. NASA-CR-114345; NASA Technical Reports Server: Hampton, VA, USA, 1971.

- Parrish, R.V.; Dieudonne, J.E.; Bowles, R.L.; Martin, D.J., Jr. Coordinated adaptive washout for motion simulators. J. Aircr. 1975, 12, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, H.; Mohamed, S.; Nahavandi, S. Incorporating human perception with the motion washout filter using fuzzy logic control. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2015, 20, 3276–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiyong, T.; Hu, M.; Zhongcai, P.; Jinhui, Z. Adaptive motion cueing algorithm based on fuzzy tuning for improving human sensation. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Chinese Guidance, Navigation and Control Conference (CGNCC), Nanjing, China, 12–14 August 2016; pp. 1200–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, N.J.; Best, M.C. Evaluation of a new body-sideslip-based driving simulator motion cueing algorithm. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2012, 226, 1433–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, A.V.; Wentink, M.; van Paassen, M.M.; Mulder, M. Comparison of three motion cueing algorithms for curve driving in an urban environment. Presence 2009, 18, 200–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazani, M.R.C.; Asadi, H.; Khoo, S.; Nahavandi, S. A linear time-varying model predictive control-based motion cueing algorithm for hexapod simulation-based motion platform. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2019, 51, 6096–6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazani, M.R.C.; Asadi, H.; Mohamed, S.; Lim, C.P.; Nahavandi, S. A time-varying weight MPC-based motion cueing algorithm for motion simulation platform. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 11767–11778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, H.; Bellmann, T.; Qazani, M.C.; Mohamed, S.; Lim, C.P.; Nahavandi, S. A novel decoupled model predictive control-based motion cueing algorithm for driving simulators. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 7024–7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biemelt, P.; Link, C.; Gausemeier, S.; Trächtler, A. A model-based online reference prediction strategy for model predictive motion cueing algorithms. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 6082–6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprecht, A.; Steffen, D.; Nagel, K.; Haecker, J.; Graichen, K. Online model predictive motion cueing with real-time driver prediction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 12414–12428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 8608:2016; Mechanical Vibration—Road Surface Profiles—Reporting of Measured Data. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Harrison, M.F. Low-Frequency Vibrations in Disk Braking Systems—Controlling the Creep-Groan Phenomenon in Road Vehicles; Professional Engineering Publishing Ltd.: Westminister, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriu, M. On the spectral representation method in simulation. Probabilistic Eng. Mech. 1993, 8, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Xiong, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Z. A Hierarchical LSTM-Based Vehicle Trajectory Prediction Method Considering Interaction Information. Automot. Innov. 2024, 7, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Song, Z.; Amini, M.R.; Hofmann, H. Internal Short Circuit Detection for Parallel-Connected Battery Cells Using Convolutional Neural Network. Automot. Innov. 2022, 5, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormsby, C.C. Model of Human Dynamic Orientation. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Qazani, M.R.C.; Asadi, H.; Bellmann, T.; Mohamed, S.; Lim, C.P.; Nahavandi, S. Adaptive washout filter based on fuzzy logic for a motion simulation platform with consideration of joints’ limitations. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 12547–12558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Chen, M.; He, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Diao, P. Research on state-parameter estimation of unmanned Tractor—A hybrid method of DEKF and ARBFNN. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 127, 107402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Index | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 64 | 256 | 1024 | 4096 | 16,384 | 65,536 | 262,144 |

| CC | RMSE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMPC | RPAMPC | AMPC | RPAMPC | ||

| C | 0.4888 | 0.5726 | 0.0657 | 0.0625 | |

| E | 0.641 | 0.6949 | 0.0544 | 0.0504 | |

| G | 0.4928 | 0.7539 | 0.0230 | 0.0172 | |

| C | 0.3106 | 0.3543 | 0.0342 | 0.0322 | |

| E | 0.5739 | 0.6077 | 0.05 | 0.0483 | |

| G | 0.4959 | 0.6958 | 0.0223 | 0.0182 | |

| C | 0.2061 | 0.4557 | 0.046 | 0.0453 | |

| E | 0.6077 | 0.6782 | 0.0381 | 0.0296 | |

| G | 0.1777 | 0.5359 | 0.043 | 0.0396 | |

| C | 0.4972 | 0.6082 | 1.2752 | 1.0362 | |

| E | 0.3608 | 0.7473 | 1.5705 | 1.1072 | |

| G | 0.4711 | 0.7354 | 0.8706 | 0.6997 | |

| C | 0.1821 | 0.2861 | 0.7694 | 0.6670 | |

| E | 0.2377 | 0.6852 | 0.9968 | 0.6623 | |

| G | 0.5741 | 0.8092 | 0.4534 | 0.3448 | |

| C | 0.6359 | 0.6391 | 0.7356 | 0.7219 | |

| E | 0.8723 | 0.8786 | 2.0270 | 1.8828 | |

| G | 0.8249 | 0.8014 | 0.4436 | 0.4386 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, X.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, L. Route-Preview Adaptive Model Predictive Motion Cueing for Driving Simulators. Actuators 2025, 14, 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120588

Jiang X, Zhang B, Chen X, Zeng H, Zhang L. Route-Preview Adaptive Model Predictive Motion Cueing for Driving Simulators. Actuators. 2025; 14(12):588. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120588

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Xue, Binghao Zhang, Xiafei Chen, Hai Zeng, and Lijie Zhang. 2025. "Route-Preview Adaptive Model Predictive Motion Cueing for Driving Simulators" Actuators 14, no. 12: 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120588

APA StyleJiang, X., Zhang, B., Chen, X., Zeng, H., & Zhang, L. (2025). Route-Preview Adaptive Model Predictive Motion Cueing for Driving Simulators. Actuators, 14(12), 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120588