Variable Control Period Model Predictive Current Control with Current Hysteresis for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Models of PMSM

3. Comparison of the Conventional FCS-MPCC and the Proposed HBVCP-MPCC

3.1. Conventional FCS-MPCC

3.2. Proposed HBVCP-MPCC

4. Implementation of Predictive Current Control with Variable Control Period

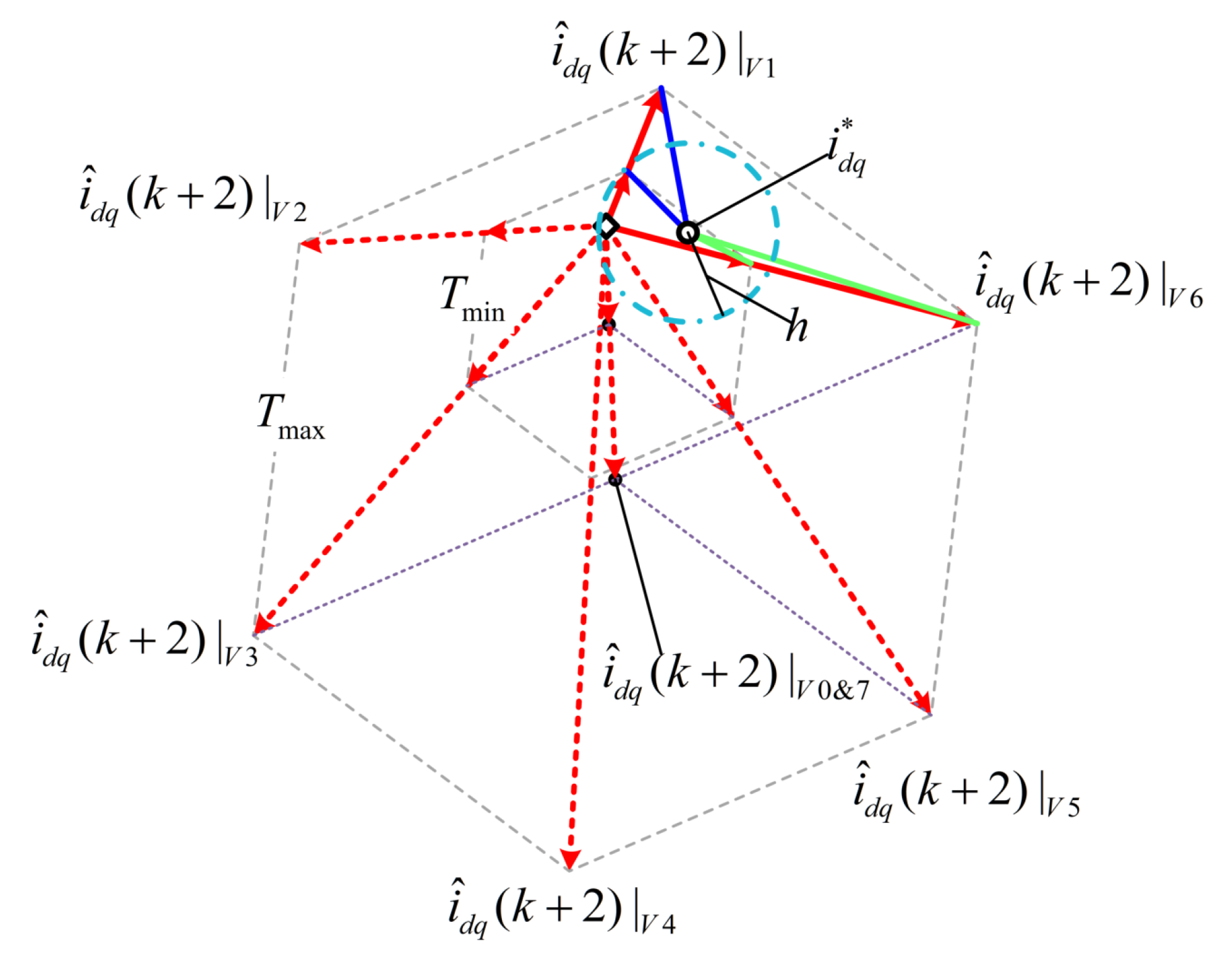

4.1. Width of Current Hysteresis and Range of Control Period

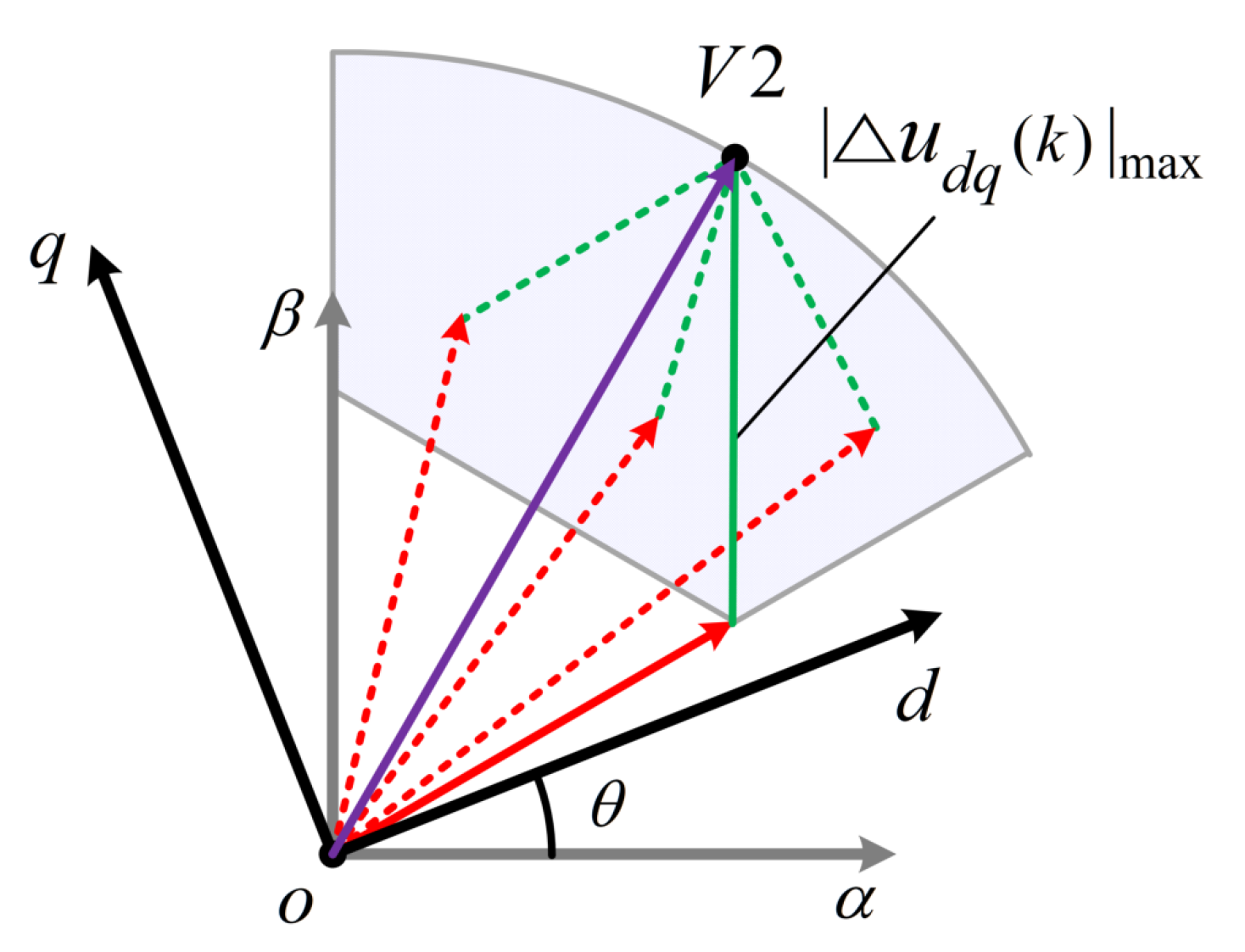

4.2. Determination of Optimal VV

4.3. Regulation of Optimal Control Period

5. Experimental Verification

5.1. Steady-State Performance Comparison

5.2. Dynamic Performance Comparison

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, H.; Lin, H. High Power Density PMSM With Lightweight Structure and High-Performance Soft Magnetic Alloy Core. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2019, 29, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouro, S.; Perez, M.; Rodriguez, J.; Llor, A.; Young, H. Model Predictive Control MPC’s Role in the Evolution of Power Electronics. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2015, 9, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, X.; Lu, S.; Guo, Y.; Song, L.; Zhao, Z. Research on Actuator Control System Based on Improved MPC. Actuators 2025, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arahal, M.; Martin, C.; Barrero, F.; Gonzalez-Prieto, I.; Duran, M. Model-Based Control for Power Converters with Variable Sampling Time: A Case Example Using Five-Phase Induction Motor Drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 5800–5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Peretti, L.; Wu, L. Model-Free Current Predictive Control for PMSMs with Ultralocal Model Employing Fixed-Time Observer and Extremum-Seeking Method. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 10682–10693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, S.; Ning, B.; Li, Y. Robust Model Predictive Control With Simplified Repetitive Control for Electrical Machine Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 4524–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Hua, W.; Chen, F.; Hu, M.; Zhu, J. Model Predictive Torque Control With SVM for Five-Phase PMSM Under Open-Circuit Fault Condition. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 5531–5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Tian, W.; Karamanakos, P.; Heldwein, M.; Kennel, R. A Direct Model Predictive Control Strategy With an Implicit Modulator for Six-Phase PMSMs. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2023, 11, 1291–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Shen, X.; Lin, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, D.; Liu, J. Robust Model Predictive Control of Position Sensorless-Driven IPMSM Based on Cascaded EKF-LESO. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 8824–8832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, C. Virtual-Vector-Based Robust Predictive Current Control for Dual Three-Phase PMSM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 2048–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Song, W.; Huang, L.; Yu, B. Double-Vector-Based Finite Control Set Model Predictive Control for Five-Phase PMSMs With High Tracking Accuracy and DC-Link Voltage Utilization. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 15234–15244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, A. FCS-MPC for Three-Level NPC Inverter-Fed SPMSM Drives Without Information of Motor Parameters and DC Capacitor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 3504–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; He, Y. Direct Voltage-Selection Based Model Predictive Direct Speed Control for PMSM Drives Without Weighting Factor. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 7838–7851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanakos, P.; Geyer, T. Guidelines for the Design of Finite Control Set Model Predictive Controllers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 7434–7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hang, J.; Ding, S.; Wang, Q. Common Predictive Model for PMSM Drives With Interturn Fault Considering Torque Ripple Suppression. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 4071–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, F.; Xu, W.; Kennel, R.; Gerling, D.; Lorenz, R. Finite-Control-Set Model Predictive Torque Control with a Deadbeat Solution for PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 5402–5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.; Shi, D.; Chen, X.; Gao, G. Ultra-Local Model-Based Adaptive Enhanced Model-Free Control for PMSM Speed Regulation. Machines 2025, 13, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Niu, S.; Li, X. A Simplified Multivector-Based Model Predictive Current Control for PMSM with Enhanced Performance. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 4032–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Bao, G. A Novel Low-Complexity Cascaded Model Predictive Control Method for PMSM. Actuators 2023, 12, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Tian, H.; Zhang, Z. Dual-Vector Predictive Current Control Strategy for PMSM Based on Voltage Phase Angle Decision and Improved Sliding Mode Controller. Machines 2025, 13, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, N.; Xing, H.; Xie, W.; Lee, C. A Novel Double-Vector Model-Predictive Current Control for PMSM With Low Computational Burden and Switching Frequency. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 11283–11295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkar, S.; Thippiripati, V. Enhanced Predictive Current Control of PMSM Drive with Virtual Voltage Space Vectors. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Ind. Electron. 2022, 3, 834–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanakos, P.; Stolze, P.; Kennel, R.; Manias, S.; Mouton, H. Variable Switching Point Predictive Torque Control of Induction Machines. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2014, 2, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, M.; Gu, X.; Yan, Y.; Xia, C. VSP predictive torque control of PMSM. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2019, 13, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Hu, S.; Bao, Z. Variable Action Period Predictive Flux Control Strategy for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 6185–6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Cui, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T. Flux-Trajectory-Optimization-Based Predictive Flux Control of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2021, 9, 4364–4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, T.; Papafotiou, G.; Morari, M. Model Predictive Direct Torque Control-Part I: Concept, Algorithm, and Analysis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2009, 56, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, T. Model Predictive Direct Current Control Formulation of the stator current bounds and the concept of the switching horizon. IEEE Ind. Appl. Mag. 2012, 18, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walz, S.; Liserre, M. Hysteresis Model Predictive Current Control for PMSM With LC Filter Considering Different Error Shapes. IEEE Open J. Power Electron. 2020, 1, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamim, W.; Jlassi, I.; Cardoso, A. A Computationally Efficient Model Predictive Current Control of Synchronous Reluctance Motors Based on Hysteresis Comparators. Electronics 2022, 11, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Song, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, C. Improved Zero-Sequence Current Hysteresis Control-Based Space Vector Modulation for Open-End Winding PMSM Drives With Common DC Bus. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 10755–10760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Rated Power | 1.6 kW | |

| Pole Pairs | 4 | |

| Inductance in Nameplate | 1.515 mH | |

| Tested Inductance in d-axis | 1.4115 mH | |

| Tested Inductance in q-axis | 1.6313 mH | |

| Stator Resistance | 0.338 | |

| Magnet Flux Amp. | 0.1105 Wb | |

| Rated Speed | 3000 rpm | |

| Rated Torque | 6 Nm | |

| Rated Current | 8 A |

| Scheme | THD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCS-MPCC (76 s) | 100 | 1000 | 37.5% | 1.99 | 3.21 | 3.49 | 24.99% |

| FCS-MPCC (40 s) | 100 | 1000 | 37.5% | 1.98 | 2.79 | 3.23 | 21.44% |

| HBVCP-MPCC | 100 | 1000 | 37.5% | 2.01 | 2.03 | 2.39 | 15.66% |

| FCS-MPCC (76 s) | 180 | 1000 | 37.5% | 2.05 | 5.75 | 6.04 | 46.67% |

| FCS-MPCC (40 s) | 180 | 1000 | 37.5% | 2.05 | 4.62 | 5.12 | 43.31% |

| HBVCP-MPCC | 180 | 1000 | 37.5% | 2.09 | 3.75 | 4.18 | 35.24% |

| FCS-MPCC (76 s) | 180 | 2500 | 75.0% | 1.83 | 6.07 | 6.50 | 37.45% |

| FCS-MPCC (40 s) | 180 | 2500 | 75.0% | 1.85 | 5.25 | 5.56 | 28.92% |

| HBVCP-MPCC | 180 | 2500 | 75.0% | 1.85 | 3.91 | 4.45 | 19.80% |

| Scheme | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCS-MPCC (76 s) | 37.5% | 2.15 | 3.16 | 3.56 |

| FCS-MPCC (40 s) | 37.5% | 2.17 | 2.66 | 3.18 |

| HBVCP-MPCC | 37.5% | 2.13 | 1.97 | 2.41 |

| FCS-MPCC (76 s) | 75.0% | 2.21 | 3.19 | 3.58 |

| FCS-MPCC (40 s) | 75.0% | 2.23 | 2.74 | 3.23 |

| HBVCP-MPCC | 75.0% | 2.27 | 2.04 | 2.37 |

| Scheme | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCS-MPCC (76 s) | 100 | 2.01 | 3.27 | 3.57 |

| FCS-MPCC (40 s) | 100 | 2.00 | 2.80 | 3.16 |

| HBVCP-MPCC | 100 | 2.03 | 2.13 | 2.52 |

| FCS-MPCC (76 s) | 180 | 2.27 | 6.04 | 6.54 |

| FCS-MPCC (40 s) | 180 | 2.23 | 4.71 | 5.42 |

| HBVCP-MPCC | 180 | 2.29 | 3.68 | 4.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, Y.; Jiang, F.; Wang, S.; Cheng, S.; Hu, Z. Variable Control Period Model Predictive Current Control with Current Hysteresis for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives. Actuators 2025, 14, 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14110517

Guo Y, Jiang F, Wang S, Cheng S, Hu Z. Variable Control Period Model Predictive Current Control with Current Hysteresis for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives. Actuators. 2025; 14(11):517. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14110517

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Yuhao, Fuxi Jiang, Siqi Wang, Shanmei Cheng, and Zuoqi Hu. 2025. "Variable Control Period Model Predictive Current Control with Current Hysteresis for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives" Actuators 14, no. 11: 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14110517

APA StyleGuo, Y., Jiang, F., Wang, S., Cheng, S., & Hu, Z. (2025). Variable Control Period Model Predictive Current Control with Current Hysteresis for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives. Actuators, 14(11), 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14110517