Abstract

This study presents a spiral pipeline robot designed for detecting and preventing oil and gas pipeline leakages. A comprehensive analysis of factors such as spiral angle, normal force, pipe material, and operating attitude is conducted based on the robot’s mechanical model in a straight pipe. This in-depth investigation determines the optimal spiral angle, normal force, pipeline material, and operating attitude to enhance the robot’s motion stability and traction performance. Using virtual prototype technology, the robot’s traction performance is simulated under various working conditions, normal forces, and attitude angles within the pipeline. An experimental platform is established to verify the impact of deflection angle, normal force, and pipeline material on traction performance. The experimental results and simulation analysis mutually validate each other, providing a reliable reference for robot design and optimization. The spiral pipeline robot and its motion strategy proposed in this study possess both theoretical value and practical application prospects in the field of oil and gas pipeline inspection and maintenance.

1. Introduction

As industrialization accelerates, nations’ demand for oil and gas resources continues to grow [1]. In this context, oil and gas pipelines, serving as essential means of energy transportation, hold a pivotal strategic position and economic value in national industrial development [2]. However, over time, various defects may gradually emerge inside these pipelines, such as leakage points, pits, and corrosion [3].

Oil and gas pipeline inspections currently rely heavily on manual methods, which have limitations and are inefficient in promptly detecting pipeline leaks [4]. In recent years, pipeline robots have emerged as effective tools to improve the accuracy and efficiency of inspections and prevent pipeline leakage accidents. These specialized devices are designed for narrow spaces and offer strong adaptability and reliability [5,6]. They can be equipped with various sensors, such as ultrasonic, infrared, and magnetic flux leakage sensors, to detect defects such as leakage points, corrosion, and pits in pipelines [7]. Additionally, pipeline robots possess data analysis and storage capabilities, allowing them to process and analyze collected information in real time and provide accurate and reliable results to maintenance personnel [8].

Researchers including Shao et al. have categorized pipeline robots into three structural types: wheeled, tracked, and non-wheeled [9]. Wheeled robots refer to robots that have drive wheels installed on their main body, creating a sealed contact with the inner wall of the pipeline, allowing the robot to move within the pipeline [10,11]. Miao et al. developed a wheeled pipeline isolation and plugging robot and investigated its dynamic characteristics during the traversal of weld seams [12]. Wheeled robots can be further classified based on their mode of motion, namely direct-wheel drive and spiral drive. Spiral drive robots are characterized as having the axis of their drive wheels at a certain angle with respect to the central axis of the pipeline, resulting in a spiral trajectory along the inner wall. A spiral pipeline robot was designed by Yonsei University in South Korea, capable of operating within branch pipelines with zero curvature radius and varying diameters [13].

Tracked pipeline robots, unlike wheeled robots, feature tracks that provide a larger contact area with the pipeline. This design offers increased friction and superior traction, resulting in more reliable operation compared to wheeled robots. Zhang et al. developed a tracked pipeline inspection robot that allows for the individual speed adjustment of each track. This enables the robot to achieve posture adjustments within the pipeline and adapt to geometric constraints present in the pipeline environment [14].

Non-wheeled pipeline robots, such as snake-like robots, utilize complex motion control algorithms to navigate and operate within pipelines [15]. Gao and other researchers proposed a multi-link magnetic wheel pipeline robot that demonstrates good control performance in linear movement, turning, wall climbing, and obstacle crossing, among other aspects. This robot can adapt to various terrains effectively [16].

In certain scenarios, robots employ tethered cable connections for their operations. In other operational environments, robots utilize wireless communication methods [17]. However, wireless communication and positioning between robots and ground base stations face technical challenges in the context of buried oil and gas pipelines. The underground environment, consisting of soil, rock, concrete, and other materials, significantly weakens communication signals, reducing their transmission distance. Moreover, communication signals in underground environments may encounter reflection, refraction, and scattering within pipelines, resulting in delays, distortions, and interference. The complexity of the pipeline environment further hinders accurate signal localization [18]. To address these challenges, researchers have proposed several solutions, such as the Kalman filter, an efficient linear optimal estimation algorithm that predicts system states based on incomplete and noisy measurement data [19,20,21]. By integrating data from various sensors such as inertial measurement units (IMU), odometers, magnetometers, and optical sensors, the Kalman filter eliminates noise and provides accurate position and attitude estimation for robots within the pipeline [22,23]. Another solution is simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), a technology that enables robots to estimate their location within an unknown environment while constructing a map of that environment. SLAM assists pipeline robots in creating a map that contains pipeline geometry, running trajectories, and other relevant information. The SLAM algorithm continuously updates the robot’s position within the map [24,25,26]. Wireless communication is also essential, and it is facilitated through radio frequency (RF) signals between robots and ground workstations. Common approaches include outdoor positioning based on relay nodes placed along a straight path [27] and utilizing the radio frequency signal of the robot within a metal pipe, eliminating the need for ground operators to possess knowledge of the pipeline map. In the latter case, a radio frequency signal transmitter and receiver capture periodic received signal fading, which is then used to establish the robot’s positioning system based on the periodic signal fading [28,29].

Spiral pipeline robots have been widely utilized in specialized operations due to their simple structure and excellent performance in bending pipelines. However, these robots still face challenges related to insufficient traction and limited load capacity. To address these issues, this study presents a spiral pipeline robot designed with environmental detection and motion control capabilities. By examining multiple factors that affect the robot’s traction performance, this research aims to enhance the work efficiency and safety of the spiral pipeline robot.

2. Pipeline Inspection Robot System Design

Figure 1 shows the main unit of the pipeline inspection robot. The external structure of the robot is composed of the robot spiral motion unit, the motor drive unit, the support unit, the battery box, the front detection and control unit, the rear detection and control unit and the upper unit. The robot specifications are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Pipeline inspection robot prototype.

Table 1.

Main technical parameters of the pipeline inspection robot.

2.1. Structure Design of Pipeline Robot

Figure 2 describes the structure of a spiral motion unit, which is an engineering component designed to operate in a pipe or similar cylindrical environment. The unit consists of three drive modules that are equidistantly positioned at 120° intervals around the circumference. Each module has a built-in spring and steering gear that both connect to a wheel frame. A driving wheel is attached to this frame using specialized bolts. The steering gear is fastened to a mounting frame with bolts, and four springs are evenly placed at the base of this frame, allowing the drive module to adapt to varying pipe diameters. The spiral motion unit has three battery compartments arranged circumferentially, and the module can be connected to a drive motor module through a coupling. The spiral motion unit features driving wheels on each module that are positioned at a specific angle, known as the spiral angle, with respect to the axis of the pipeline. This orientation enables the generation of a driving force along the pipeline through a mechanism.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of spiral motion unit structure.

Figure 3 illustrates the central motor module positioned at the center of the robot. The central motor is connected to the large bevel gears via the output end, while the three small bevel gears are evenly distributed circumferentially, with a separation of 120 degrees between each gear. The small bevel gears are securely affixed to the lead screw, and upon driving the large bevel gears, the three small bevel gears commence rotation. This rotational motion is transmitted to the synchronous belt and the lead screw, thereby inducing movement of the lead screw nut. By compressing the spring around the smooth rod, the screw nut propels the entire drive module along the pipe’s diameter. Consequently, this motion instigates a variation in the positive pressure between the driving wheel and the inner wall of the pipe. To monitor the contact pressure between the driving wheels and the inner wall of the pipeline, pressure sensors are strategically placed between each driving module and its corresponding spring. By adjusting the spring compression of the central motor, it is possible to control the positive pressure exerted by the driving wheel, ensuring optimal performance and adaptability to various pipeline conditions.

Figure 3.

Structure diagram of the central motor.

The motor driving unit is a crucial component of the system and primarily consists of a stepper motor, connecting rod, round nut, and battery box. As illustrated in Figure 4, the battery housing serves as the primary support for the motor drive unit, with front and rear baffles connected by connecting rods. These rods are secured with four nuts on each side. The stepper motor is attached to one side baffle, and it powers the front and side spiral motion units to move circularly around the pipeline axis, enabling the robot to travel in a helical pattern within the pipeline. To supply the necessary power, the battery box is designed with four compartments to accommodate four lithium batteries.

Figure 4.

Structure diagram of motor drive unit with battery box.

The support module, an essential component of the system, is composed of a support wheel, lifting column, support seat, spring, and smooth bolt. Figure 5 illustrates the structure of the support module. The support seat serves as the main structural support, with three supporting units connected to the support frame by welding at 120° intervals around the circumference. The support module is designed to adapt to varying pipe diameters, ensuring that the support wheel maintains vertical contact with the inner wall of the pipe, providing effective support. Connected to the drive motor module through the rear support body, the support module can balance reverse torque generated during rotation. The support wheel is mounted on the wheel frame using child and mother bolts. The lifting column, equipped with a built-in spring, can move up and down to enable the support module to adapt to changes in pipe diameter, ensuring its effectiveness in providing the necessary support under different pipeline conditions.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of support unit structure.

2.2. Control System Design

Figure 6 presents the control system of the pipeline inspection robot. The robot’s CPU is an STM32-F103 chip, while the console utilizes an embedded industrial computer. The pipeline inspection robot communicates with the industrial computer via wireless communication, and the robot CPU directs the robot to operate within the pipeline based on the commands provided by the operator using the industrial computer. Additionally, the robot performs defect detection and information collection functions within the pipeline.

Figure 6.

Control system diagram.

The robot control system encompasses the robot motion control unit, the pipeline information acquisition unit, and the wireless communication unit. The pipeline information acquisition unit collects images and environmental data from within the pipeline. Image information includes defects such as cracks, leakages, pits, and corrosion. Image acquisition is achieved through two infrared night vision cameras with autofocus capabilities, positioned at the front and rear of the robot.

The front camera rotates and continuously scans around the pipeline’s axis during the robot’s spiral advancement, capturing defect information in the dark pipeline environment and fulfilling the 360° detection requirements for the pipeline’s inner wall. The rear camera supports the robot’s navigation and positioning functions within the pipeline, continuously outputting and storing images in real time. The collected environmental information encompasses gas concentrations, pipe diameters, and pipe temperatures.

The robot motion control unit governs the deflection angle of the three steering motors and the speed of the stepper motor and the central motor, adjusting the robot’s posture, speed, and bending mode while operating in the pipeline. Pressure sensors measure the pressure between the driving wheel and the pipeline’s inner wall, and the error value between the current pressure and the target pressure for the specific application is calculated. This error signal serves as the output signal for PID control, directing the central motor to adjust the positive pressure in order to achieve the desired robot traction force and improve the robot’s working efficiency within the pipeline.

Pipeline robots employ visual positioning methods within pipelines, utilizing images and point cloud data gathered by front and rear cameras, as well as laser ranging sensors, to ascertain the robot’s position and orientation within the pipeline. The process involves several specific steps: (1) data collection: images and point cloud data are collected by the robot’s cameras and laser ranging sensors; (2) feature extraction: the scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT) algorithm is employed to extract relevant features conducive to positioning, such as pipeline defects; (3) feature matching: the extracted features in the current image or point cloud data are matched with previously collected data or features in a pre-constructed map; (4) motion estimation: by matching pairs of feature points, the relative motion of the robot between two instances can be estimated; and (5) fusion and optimization: the estimated motion information is integrated into the robot’s positioning system, along with data from other sensors, such as odometers and inertial navigation systems.

Wireless communication leverages radio frequency (RF) technology to facilitate data transmission between pipeline robots and ground control centers. Utilizing specific frequency bands and modulation modes, low-frequency RF signals can minimize signal attenuation in underground environments. Low-frequency signals experience relatively less loss when penetrating underground structures, thereby enhancing communication distances. In the communication between pipeline robots and ground control centers, multiple antennas are installed on both the robots and the control stations to transmit signals simultaneously across multiple channels. This can counteract, to some extent, the multipath effect (where communication signals in underground environments may reflect, refract, and scatter within the pipe) and signal attenuation (as wireless signals experience attenuation when passing through underground structures). Signal attenuation is particularly pronounced when traversing metal, water, or other high-density materials, resulting in limited communication distances. Employing relay nodes for segmental signal transmission can increase communication distances and signal coverage. In pipeline robot-to-ground communication, multiple relay nodes are deployed to enable multi-hop transmission. When direct communication is hindered by signal attenuation and environmental obstacles, signals can be transmitted sequentially through relay nodes, allowing for longer-distance and more reliable communication.

2.3. Design of PID System for Pressure Regulation

The PID control principle is shown in Figure 7. The PID control system comprises the following components: a stepper motor, a lead screw nut, a spring, and a pressure sensor. The stepper motor controls the movement of the lead screw nut by adjusting the number of steps, thereby altering the compression of the spring and generating the corresponding elastic force. Simultaneously, the pressure sensor is utilized to measure the actual level of elastic force exerted by the spring. Assuming that the spring stiffness is k, the damping coefficient is b, the lead of the screw nut is , and the angle of the stepper motor is , then the displacement of the screw nut can be expressed as:

Figure 7.

PID control schematic diagram.

The spring force F(t) can be expressed as:

The transfer function of the system composed of a screw nut and a spring can be obtained by means of the Laplace transform:

The stepper motor transfer function is simplified to a first-order inertial system, Km is the angle coefficient of the stepper motor, T is the time constant of the stepper motor, and the transfer function is:

The whole system transfer function is:

The transfer function of the PID controller is:

By repeatedly adjusting the parameters , and of the three links, the PID control system with a fast response and small steady-state error can be obtained.

3. Robot Motion Characteristic Analysis and Mechanical Model Establishment

3.1. Analysis of Robot Traction Characteristics

As shown in Figure 8, in the given context, represents the traction force of the robot, while denotes the driving force acting on the driving wheel during the rotation process of the driving module. is the lateral force generated by the side-sliding of the driving wheel as the robot spirals through the pipeline. denotes the positive pressure of the driving wheel, and signifies the spiral angle. Additionally, represents the angle between the actual and expected running direction of the robot. The deflection stiffness coefficient of the driving wheel is represented by , and the dynamic friction coefficient is denoted by . is the sideslip rate.

Figure 8.

Traction analysis model.

The sideslip rate can be expressed as:

The sideslip force can be expressed as:

The robot can generate traction under the following conditions:

Under ideal conditions, where the driving wheel supplies enough friction force and no slipping takes place, the traction force of the robot can be described as a function of the variables discussed earlier. Assuming that (where is the spiral angle and represents the ideal angle for effective traction),

Based on this analysis, the traction force and spiral angle of the robot operating within the pipe are related to the positive pressure exerted by the robot, the contact between the driving wheel and the inner wall of the pipe, and the pipe material. As the spiral angle increases, the robot’s traction force also increases, reaching a maximum value at an optimal angle. Beyond this point, the traction force begins to decrease gradually. Thus, it is essential to find the optimal spiral angle to maximize the traction force and ensure efficient robot performance within the pipeline.

3.2. Robot Positive Pressure Analysis in Pipeline

When it comes to pipeline operations, robots are required to not only move forward and backward, but also to rotate around the axis of the pipeline. This necessitates that the driving wheels of the robot exert appropriate normal forces against the inner wall of the pipeline while maintaining an optimal operational posture angle, as shown in Figure 9a. The posture angle, denoted as , is defined as the angle between the support module and the XZ plane. The total enclosed force between the driving wheels and the inner wall of the pipeline is represented by . The slope of the pipeline with respect to the horizontal plane is defined as .

Figure 9.

(a) Normal force distribution diagram. (b) Relationship between driving factor and attitude angle.

The parameter is defined as the driving factor, which represents the ratio of the robot’s weight to the enclosed force. It serves as a measure of the contribution of the robot’s own weight to the traction force.

From the above equation, it can be observed that the robot’s pose angle affects the driving factor. Therefore, in order to maximize the utilization of the driving factor and enhance the robot’s traction performance, it is beneficial to increase the normal force and select the optimal pose angle. When operating in a horizontal straight pipe, as shown in Figure 9b, it is evident that the optimal pose angles for the robot are 0°, 120°, and 240°, where the robot achieves the maximum driving factor.

3.3. The Trajectory of the Robot’s Spiral Motion in the Pipe

An XYZ coordinate system is established along the running direction of the robot, as illustrated in Figure 10a. As the pipeline robot moves within the pipeline, smooth movement can be achieved by ensuring that the spiral angle of the driving wheel is consistent across all driving modules. The cross-section of the pipeline robot is circular, and the parametric equation for this circle can be expressed as follows:

Figure 10.

(a) Theoretical running trajectory of the robot within the pipeline. (b) Actual running trajectory of the robot as it moves through the pipeline.

Rp represents the radius of the circle (in mm); considering that the radius of the driving wheel can be ignored, it can be replaced by the length of the pipeline robot’s driving arm. denotes the rotation angle (in degrees) of the pipeline robot’s driving arm around its center.

The spiral angle is formed between the driving wheel and the pipeline axis, causing the driving wheel’s path along the inner wall of the pipeline to form a helical trajectory. Based on the geometric relationship, the linear displacement of the helix along the Z-axis is , and the trajectory line Hs(α) of the helical motion can be expressed as follows:

Mathematica software was employed to validate the Hs(α) trajectory. With Rp set to 200 mm, at 30°, and ranging from 0° to 360°, the actual running trajectory curve of the robot was obtained, as depicted in Figure 10b.

4. Influencing Factors and Simulation Analysis of Robot Traction Performance

A prototype model was created using ADAMS simulation software. The robot was imported into ADAMS, and its structure was simplified by retaining only the components associated with the transmission. This process led to the final establishment of the virtual prototype model for the pipeline robot.

4.1. Influence of Different Materials on Traction Performance of Robot in Straight Pipe Operation

The material used for oil pipelines is typically stainless-steel composite steel pipe, which is generally coated with an anti-corrosive layer on the inside, providing good corrosion resistance. Gas pipelines, on the other hand, are primarily made from steel, aluminum, or plastic pipes. Consequently, the traction force exerted by the pipeline robot varies depending on factors such as the transportation medium, transportation pressure, and pipe material. As demonstrated earlier, the traction force of the pipeline robot relies on the friction force between the driving wheel and the inner wall of the pipeline. This study investigates the difference in traction force for the pipeline robot under various working conditions and analyzes the magnitude of the traction force by simulating and altering its contact friction coefficient.

The traction force acting under different working conditions was simulated in ADAMS. First, the optimal spiral angle was set to 40°, and the contact force parameters between the driving wheel and the inner wall of the pipeline were established. The working condition refers to the operating state of the robot in various environments. Material 1 and Material 2 represent the materials of the driving wheel and the pipeline, respectively, and the stiffness coefficient K is 2855. The force index e is 1.1; the damping c is 0.57; the penetration depth d is 0.1; mus denotes the coefficient of static friction, while mud represents the coefficient of dynamic friction; vs is the static translation velocity; and vd corresponds to the friction translation velocity. Additional simulation parameters for different working conditions are presented in Table 2 below. The pipe diameter is set at 200 mm, and the robot’s running time is 5 s.

Table 2.

Contact parameters of robot and pipeline simulation.

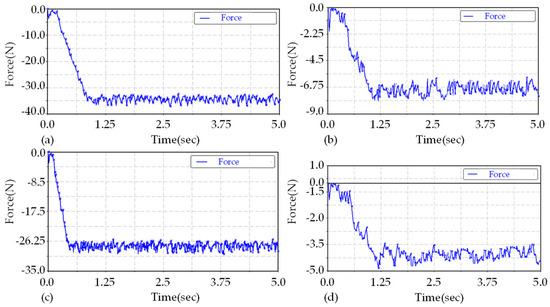

In the ADAMS simulation process, the traction force of the robot in operation can be simulated by placing a tension spring between the pipeline robot and the pipeline. The tension and compression spring is positioned on the pipeline axis. One end is connected to the robot’s center, and the other end is connected to the center of the vertical plane passing through the pipeline axis. The spring’s stiffness coefficient is set to 800, and the damping coefficient is set to 0.5. The simulation results of traction force in a straight pipe are shown in Figure 11 below.

Figure 11.

(a–d) Traction forces of the robot in the straight pipe under working conditions 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

According to the simulation results, the tension of the tension spring in the four simulated operating conditions in the straight pipe will slip as the robot accelerates to its maximum speed. The maximum traction of the robot will fluctuate within a small range, and the traction will increase with the friction coefficient. The difference in the transportation medium within the pipe made from the same material will also impact the traction force. The tractive force of the robot running in a pipeline without a transport medium is significantly greater than that in a pipeline containing a medium.

4.2. Influence of Positive Pressure on Traction Performance of Robot Support Wheel

The pipeline robot is designed with three groups of supporting wheels, distributed at a 120-degree circumference, and each supporting wheel has a normal pressure with the inner wall of the pipeline. The appropriate normal pressure is crucial for the robot’s performance. Excessive normal pressure will result in high power consumption, while insufficient positive pressure will prevent the robot’s driving wheel from generating enough friction with the pipeline’s inner wall. In the analysis of normal force, the pipeline was set with no medium transport, the material was plexiglass, the coefficient of static friction was 0.2, the coefficient of dynamic friction was 0.15, and the simulation time was 10 s.

The normal force of the driving wheel was set at 100 N, 110 N, 120 N, and 130 N, respectively, and the simulation results met the requirement of traction force greater than 30 N, as shown in Figure 12 below. The tractive forces were 33 N, 36 N, 38 N, and 38 N, respectively. The traction of the driving wheel increases with the increase in positive pressure. However, when the positive pressure reaches a certain value, the traction will no longer increase, because the robot’s maximum load capacity has an upper limit, ultimately causing the robot to become stuck in the pipeline and unable to function normally. Consequently, the normal force should be controlled between 100 N and 120 N, ensuring that the robot can run smoothly in the pipeline while consuming less power.

Figure 12.

Tractive forces of the pipeline robot under different positive pressure settings. (a–d) Tractive forces when the positive pressures are 100 N, 110 N, 120 N, and 130N, respectively.

4.3. Analysis of the Influence of Robot Attitude Angle on the Rotation of the Support Unit

When the spiral pipeline robot travels within a pipeline, its spiral module rotates around the pipeline axis, while the support module serves to balance the counter torque generated by the spiral module. Consequently, the robot not only moves forward and backward inside the pipeline but also rotates around the pipeline axis, resulting in a change in the robot’s motion posture that deviates from its initial position. The support module is distributed circumferentially at 120-degree intervals. Although deviations in the robot’s motion posture do not impact its operation, it must maintain the optimal posture for entering bends as it navigates them. Furthermore, during the operation of the robot’s towing cable module, posture deviations can cause the cable to become entangled, necessitating limits and corrections to the robot’s posture deflection.

Based on the analysis in Section 3.2, different attitude angles affect the robot’s torque. Therefore, four representative attitude angles of 0°, 30°, 60°, and 90° were selected for further examination. The simulation results are shown in Figure 13. In the 0–90° attitude angle range, the support module’s rotational torque increases gradually with the rising attitude angle. When the attitude angle reaches 90°, the torque is at its maximum, and when the angle is 0°, the torque approaches zero. By adjusting the robot’s attitude angle to 0 degrees and maximizing the positive pressure between the support unit and the pipeline’s inner wall, the torque of the robot’s support unit can be reduced, effectively restraining the support unit’s rotation along the pipeline axis.

Figure 13.

Robot torque of different attitude angles.

5. Traction Experiment Verification and Analysis

An experimental platform was constructed for the pipeline robot. As shown in Figure 14, one end of the spring is attached to the pipeline robot, while the other end is connected to a force sensor. The sensor remains fixed in a specific position, and the robot initiates its operation within the pipeline. This setup enables researchers to systematically analyze the performance of the robot under various conditions, optimizing its design for maximum efficiency and functionality.

Figure 14.

Robot traction experiment test environment.

In this experiment, steel and plexiglass pipes are utilized as materials. Industrial lubricating oil is applied to simulate the conditions of a medium under actual operation. During the robot’s operation, when a slip occurs, the force sensor will cease data collection. The tractive force of the robot is influenced by factors such as normal force, spiral angle, pipe contact, and motor driving force. The spiral angle, pipe material, and driving wheel normal force were chosen as variables, with the peak value collected by the sensor being considered as valid data. A 42-series motor (the drive motor in the drive module of the robot) was employed as the driving motor for the robot prototype, and the torque was set at 10 Nm.

The test results are displayed in Figure 15a, and the trend of traction force variation is generally consistent with the theoretical analysis. The traction force initially increases and then decreases with the increase in the spiral angle; however, there is a significant deviation from the theoretical analysis under conditions with small spiral angles. In sections with small spiral angles, the pipe wall cannot provide sufficient friction, making it prone to slippage and unsmooth operation. As the spiral angle increases, the slippage gradually disappears.

Figure 15.

(a) Experiment involving the robot under various working conditions; (b) experiment with the robot operating under different normal forces.

Among the four experimental working conditions, the steel pipe (dry) has the largest friction factor, and the optimal spiral angle is approximately 40°, followed by the plexiglass pipe (dry), with its optimal spiral angle at around 50°. Therefore, the optimal spiral angle for robot traction tends to increase as the friction factor decreases. Consequently, the robot’s spiral angle should be set based on different working conditions and varying spiral angles. The tractive force of running in a steel pipe (dry) is greater than that of running in a plexiglass (dry) pipe.

In the steel pipe (dry) condition, the robot operates with a large traction force due to its relatively high friction factor. The higher the friction factor, the greater the traction force. In pipelines made from the same material, the tractive force of the robot’s operation in a pipeline with a transport medium is significantly lower than in a pipeline without a transport medium.

In the experiment, the robot’s experimental working condition was set as a plexiglass pipe, and three different values of 100 N, 110 N, and 120 N were established by adjusting the normal force of the driving wheel. The normal force was monitored using a drive wheel pressure sensor, and each peak traction was recorded as a data collection point during the test. The test results, shown in Figure 15b, exhibit the same variation trend as the simulation, although they are smaller than the simulation value. Under the same working conditions, the optimal spiral angle of the robot is approximately 40 degrees, and the optimal spiral angle does not change as the normal force increases.

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- In this study, a spiral pipeline robot designed for oil and gas pipeline detection is presented, and a corresponding mechanical model is constructed. The robot’s traction performance is investigated through dynamic simulations, and the simulation results are verified by experiments. It is found that the tractive force is closely related to the normal force, helix angle, contact between the driving wheel and the pipe, and the pipe material. In the small helix angle range, the robot is prone to skidding. As the helix angle increases, the skidding phenomenon gradually decreases, and the tractive force initially increases before decreasing. When the helix angle reaches 90°, the tractive force becomes zero.

- (2)

- Under different working conditions, the robot’s traction force displays an increasing trend with the rise in the friction coefficient, but the optimal helix angle decreases. Therefore, it is necessary to adjust the appropriate deflection angle based on the actual working condition. In pipelines of the same material, the presence or absence of a transport medium affects the tractive force, with the force in dry pipelines being significantly higher than that in pipelines containing a transport medium. The variable helix angle bending strategy enables the robot to exhibit good passing performance in bending pipes and offers better stability than a fixed helix angle bending.

- (3)

- Under the same working conditions, the robot’s traction force can be improved by adjusting the normal force of the driving wheel. The greater the normal force, the greater the traction. When the normal force changes, the optimal helix angle for traction remains at approximately 40° without significant change. Moreover, the motion stability of the robot is a critical issue affected by various factors, such as the center of gravity’s position and inertial force. To enhance motion stability and traction, the robot structure and control algorithm should be optimized, and a balance between various factors should be achieved.

Author Contributions

Equipment design and manufacturing process, H.Y.; Prototype processing and manufacturing, P.Z. and H.Y.; Control systems and software development, P.Z. and C.X.; Writing and review, H.Y. and S.J.; Simulation analysis, P.Z. and X.W.; Experimental support, D.Z. and H.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is part of a project that has received funding from the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province: “Research on the Kinematics Characteristics of the Driving Mechanism for Leakage Blocking Repair in Multi-point Dispersed Sections of Pipelines (20210302123038)” and the special project of scientific and technological cooperation and exchange in Shanxi Province: “Intelligent equipment technology for defect detection and emergency prevention and control in dangerous source pipe” (202104041101001) and a research project supported by Shanxi Scholarship Council of China ”Research on screw driven pipeline robot for leakage plugging and repairing technology ”(2020–110) and North University of China Science and Technology project “Research on Circumferential Welding Robot Technology of Pipeline Internal weld” (20221817). The authors would like to express their gratitude for the support for this study. Moreover, the authors sincerely thank Professor Wu Wenge of North University of China for his critical discussion and Dr. Dahua Xie of Silicon Valley, USA for linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This research was generously supported by the following organizations, to which we express our sincere gratitude: Shanxi Provincial Key Laboratory of Advanced Manufacturing, North University of China; Taiyuan University of Technology National and Local Joint Engineering Laboratory of Mine Fluid Control; Shanxi Datong University Coal Mine Electromechanical Technology Institute; Shanxi Coal Import and Export Group Science and Technology Research Institute Co., Ltd.; and Shanxi Honganxiang Science and Technology Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yan, H.; Wang, L.; Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Hou, X. Research on Passing Ability and Climbing Performance of Pipeline Plugging Robots in Curved Pipelines. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 173666–173680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, F.; Tu, C.; Tian, M.; Wang, X. Elastic Obstacle-Surmounting Pipeline-Climbing Robot with Composite Wheels. Machines 2022, 10, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, X.; Jiang, X.; Ma, R. Construction of fluid-solid coupling model of flexible multibody system for pipeline robots driven by differential pressure. Nongye Gongcheng Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, F. Inspection Robot for Submarine Pipeline Based on Machine Vision. In Proceedings of the 2021 Asia-Pacific Conference on Image Processing, Electronics and Computers, IPEC 2021, Dalian, China, 14–16 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Torajizadeh, H.; Asadirad, A.; Mashayekhi, E.; Dabiri, G. Design and manufacturing a novel screw-in-pipe inspection robot with steering capability. J. Field Robot. 2022, 40, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Sang, H.; Xing, Y.; Lu, Y. Design of wireless in-pipe inspection robot for image acquisition. Ind. Robot.-Int. J. Robot. Res. Appl. 2023, 50, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Yang, S.U.; Choi, Y.S.; Mun, H.M.; Park, C.M.; Choi, H.R. Design of back-drivable joint mechanism for in-pipe robot. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, IROS 2015, Hamburg, Germany, 28 September–2 October 2015; pp. 3779–3784. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Li, J.; Kou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, L. Research on the Traction and Obstacle-Surmounting Performance of an Adaptive Pipeline-Plugging Robot. Stroj. Vestn.-J. Mech. Eng. 2022, 68, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Wang, Y.; Guo, B.; Chen, X. A review over state of the art of in-pipe robot. In Proceedings of the 12th IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation, ICMA 2015, Beijing, China, 2–5 August 2015; pp. 2180–2185. [Google Scholar]

- Kazeminasab, S.; Aghashahi, M.; Katherine Banks, M. Development of an Inline Robot for Water Quality Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Robotics and Automation Engineering, ICRAE 2020, Singapore, 20–22 November 2020; pp. 106–113. [Google Scholar]

- Waleed, D.; Mustafa, S.H.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Abdel-Hafez, M.F.; Jaradat, M.A.K.; Dias, K.R.; Arif, F.; Ahmed, J.I. An In-Pipe Leak Detection Robot with a Neural-Network-Based Leak Verification System. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 1153–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Zhao, H.; Gao, B.; Ma, Y.; Hou, Y.; Song, F. Motion analysis and control of the pipeline robot passing through girth weld and inclination in natural gas pipeline. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 104, 104662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Park, J.; Hyun, D.; Yook, G.; Yang, H.-s. Novel mechanisms and simple locomotion strategies for an in-pipe robot that can inspect various pipe types. Mech. Mach. Theory 2012, 56, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, L.; Kim, J. Design and Analysis of Independently Adjustable Large In-Pipe Robot for Long-Distance Pipeline. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljebck, P.; Pettersen, K.Y.; Stavdahl, O.; Gravdahl, J.T. A review on modelling, implementation, and control of snake robots. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2012, 60, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Huang, M.; Tang, K.; Lang, X.; Gao, J. Design, Analysis, and Control of a Multilink Magnetic Wheeled Pipeline Robot. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 67168–67180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. Data Collection in MI-Assisted Wireless Powered Underground Sensor Networks: Directions, Recent Advances, and Challenges. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2021, 59, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worley, R.; Yu, Y.; Anderson, S. Acoustic Echo-Localization for Pipe Inspection Robots. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Multisensor Fusion and Integration for Intelligent Systems, MFI 2020, Karlsruhe, Germany, 14–16 September 2020; pp. 160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Maneewarn, T.; Thung-Od, K. ICP-EKF localization with adaptive covariance for a boiler inspection robot. In Proceedings of the 7th IEEE International Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent Systems, CIS 2015 and the 7th IEEE International Conference on Robotics, Automation and Mechatronics, RAM 2015, Siem Reap, Cambodia, 15–17 July 2015; pp. 216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira, E.; Azzolin, R.; Botelho, S.; Oliveira, V. Sensors data fusion to navigate inside pipe using Kalman Filter. In Proceedings of the 21st IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation, ETFA 2016, Berlin, Germany, 6–9 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Mittmann, E.; Winston, C.; Youcef-Toumi, K. A practical minimalism approach to in-pipe robot localization. In Proceedings of the 2019 American Control Conference, ACC 2019, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 10–12 July 2019; pp. 3180–3187. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Krys, D. The use of laser range finder on a robotic platform for pipe inspection. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2012, 31, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirandish, M.; Yazdi, E.A.; Mohammadi, H.; Mohammadi, M. A fault-tolerant sensor fusion in mobile robots using multiple model Kalman filters. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 161, 104343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Schirru, M.; Zahraee, A.H.; Dwyer-Joyce, R.; Boxall, J.; Dodd, T.J.; Collins, R.; Anderson, S.R. PipeSLAM: Simultaneous Localisation and Mapping in Feature Sparse Water Pipes using the Rao-Blackwellised Particle Filter. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics, AIM 2017, Munich, Germany, 3–7 July 2017; pp. 1459–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Aitken, J.M.; Evans, M.H.; Worley, R.; Edwards, S.; Zhang, R.; Dodd, T.; Mihaylova, L.; Anderson, S.R. Simultaneous Localization and Mapping for Inspection Robots in Water and Sewer Pipe Networks: A Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 140173–140198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, T.-Y.; Sung, C.-C. Learning and SLAM based decision support platform for sewer inspection. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chatzigeorgiou, D.; Youcef-Toumi, K.; Ben-Mansour, R. Node Localization in Robotic Sensor Networks for Pipeline Inspection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2016, 12, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, C.; Kumar, V.; Lera, F.; Villarroel, J.L. RF odometry for localization in pipes based on periodic signal fadings. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, IROS 2014, Chicago, IL, USA, 14–18 September 2014; pp. 4577–4583. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, C.; Seco, T.; Espelosin, J.; Lera, F.; Villarroel, J.L. An alternative approach for robot localization inside pipes using RF spatial fadings. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2021, 136, 103702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).