Antimicrobial Effect of Oregano Essential Oil in Na-Alginate Edible Films for Shelf-Life Extension and Safety of Feta Cheese

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Microbial Cultures

2.3. Na-Alginate Edible Films

2.4. Inoculation and Preparation of Cheese Samples

2.5. Microbiological Analyses and pH Measurements

2.6. Sensory Assessment

2.7. Multispectral Imaging Analysis

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

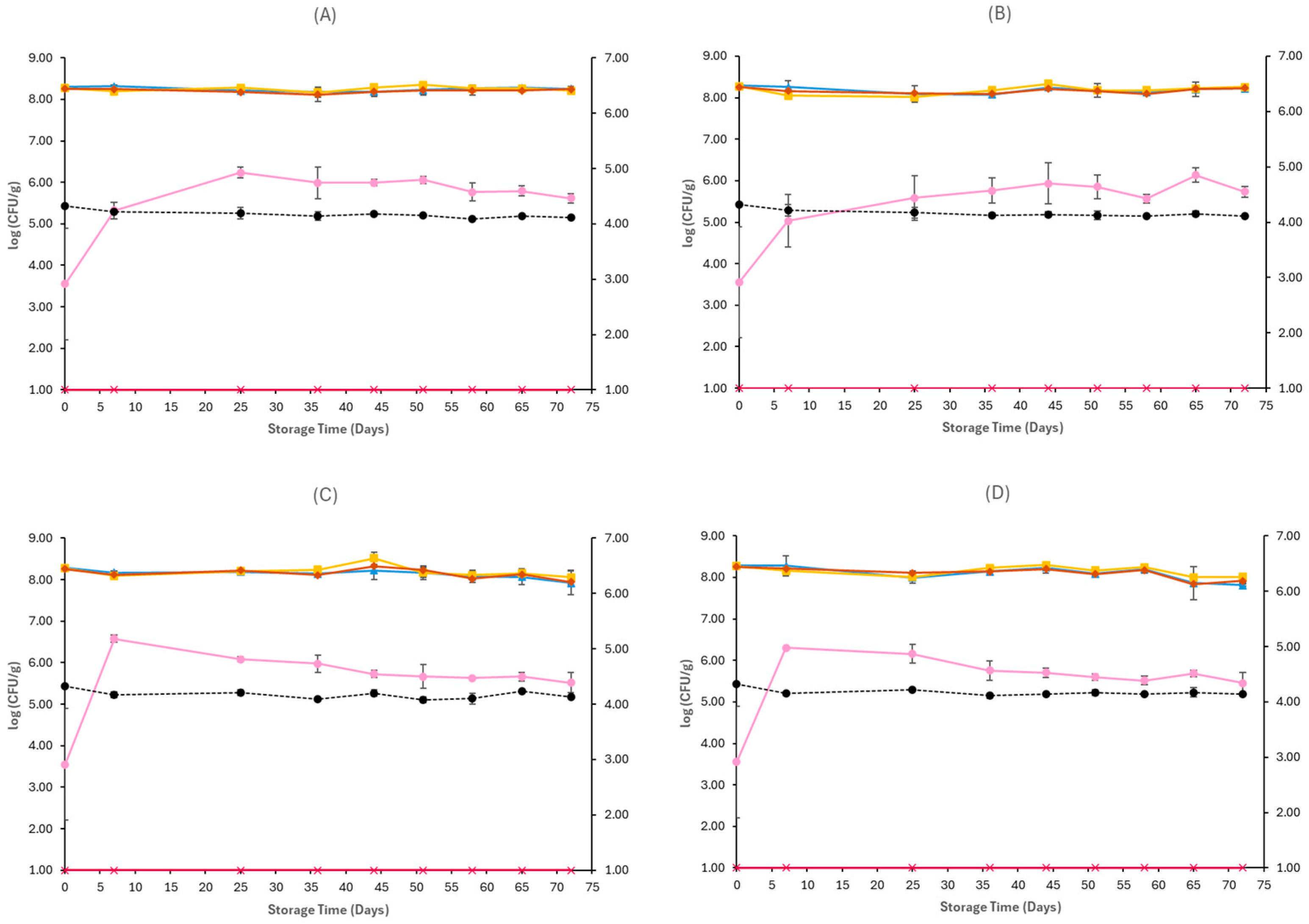

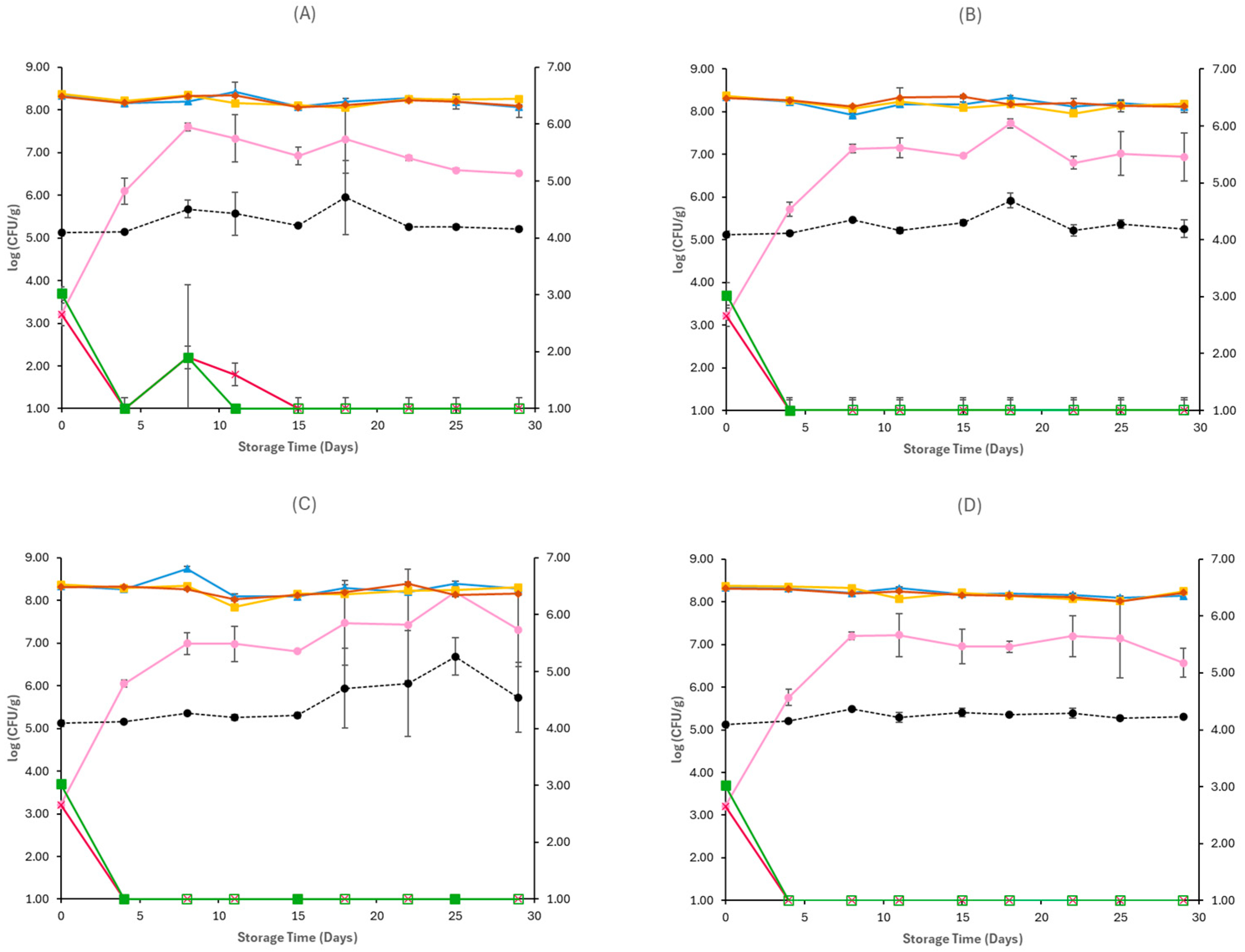

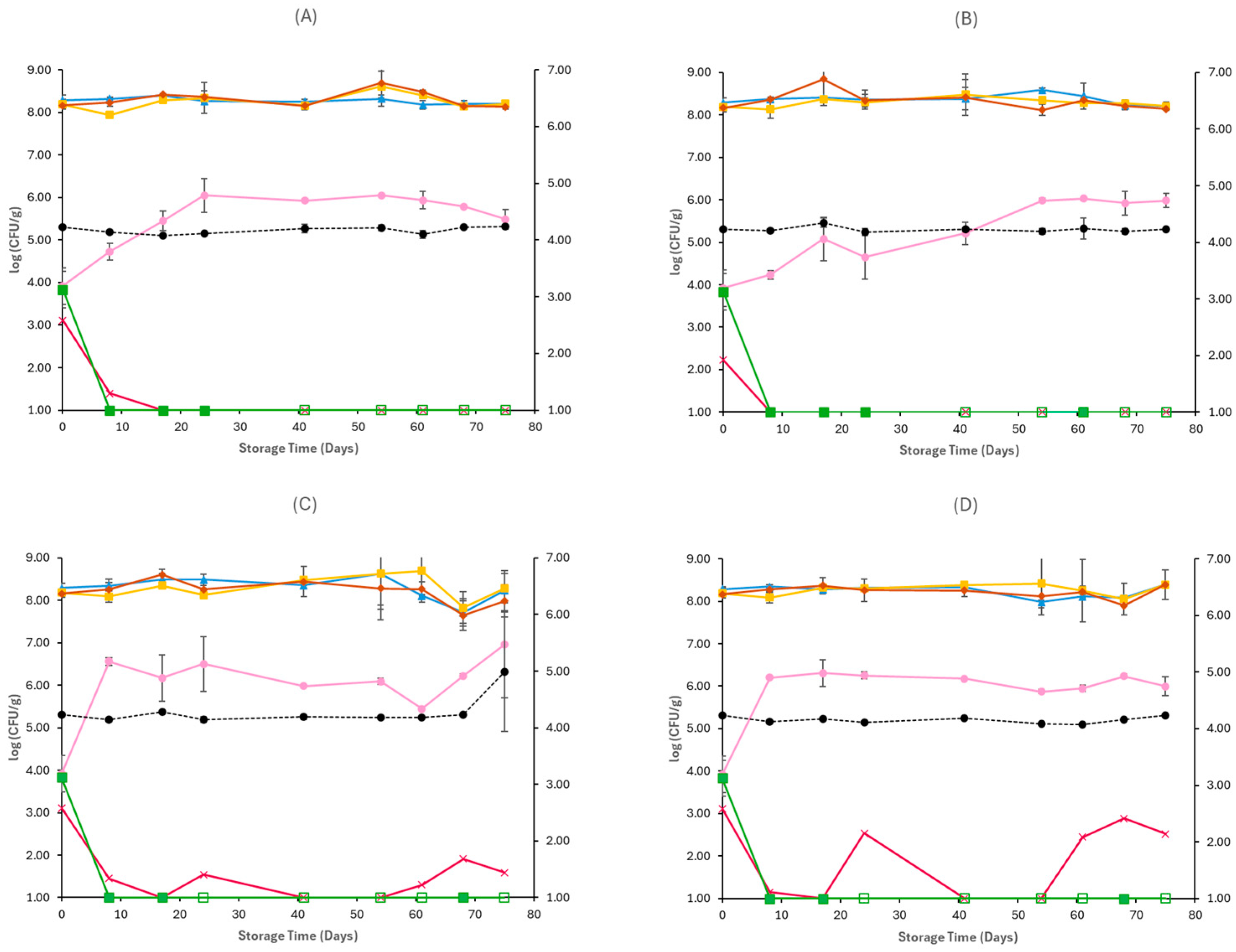

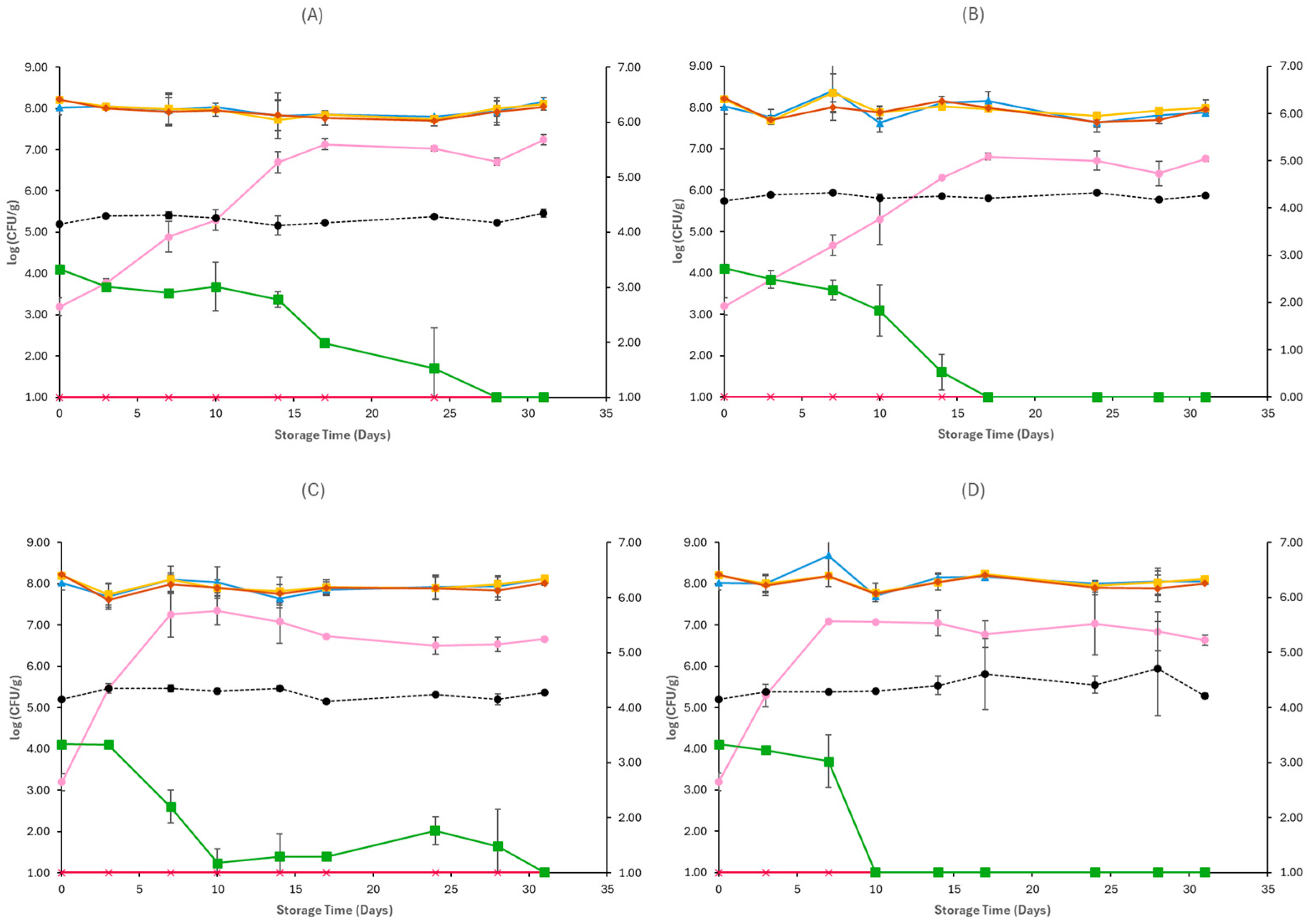

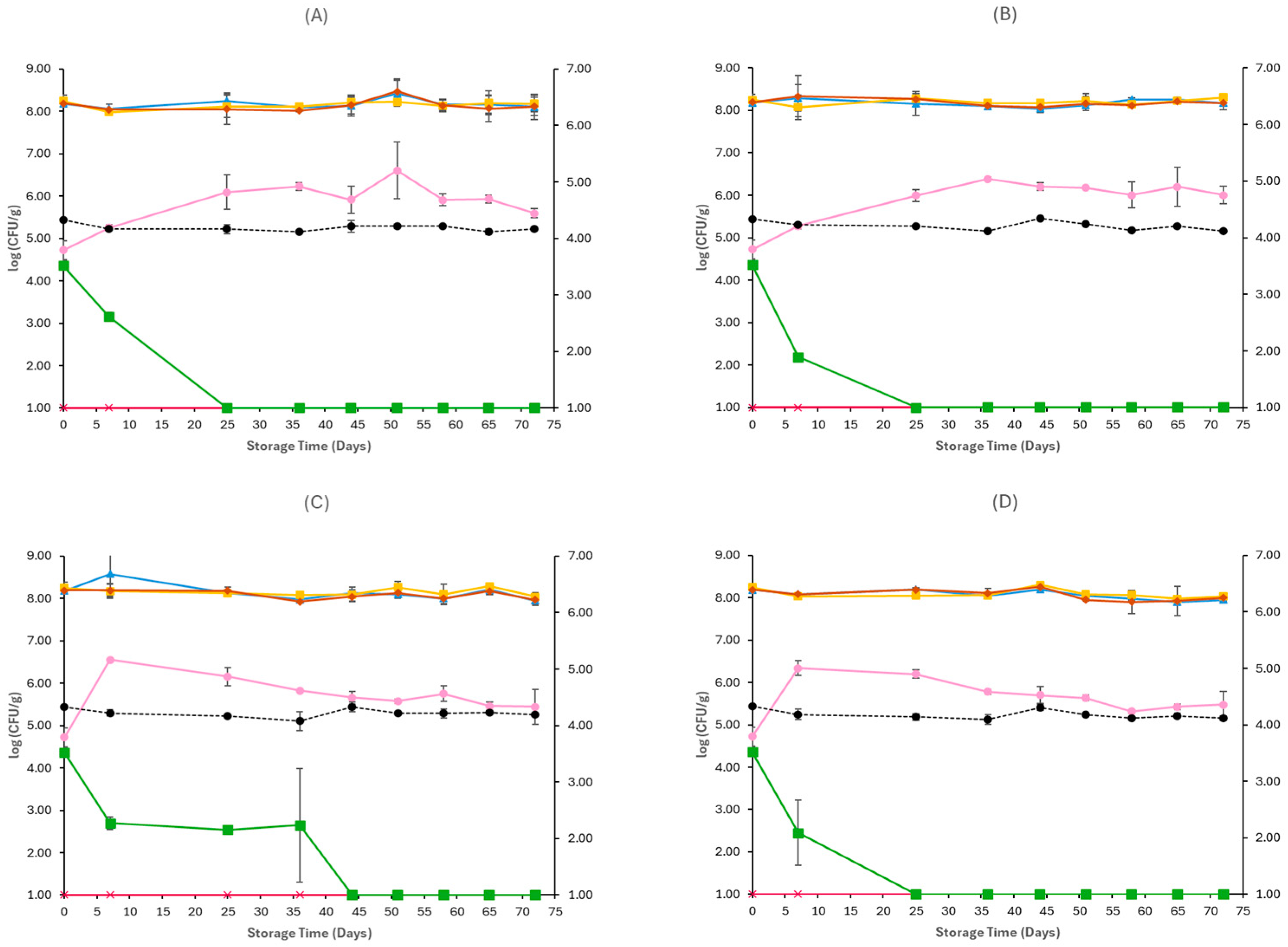

3.1. Microbiological Analyses and pH

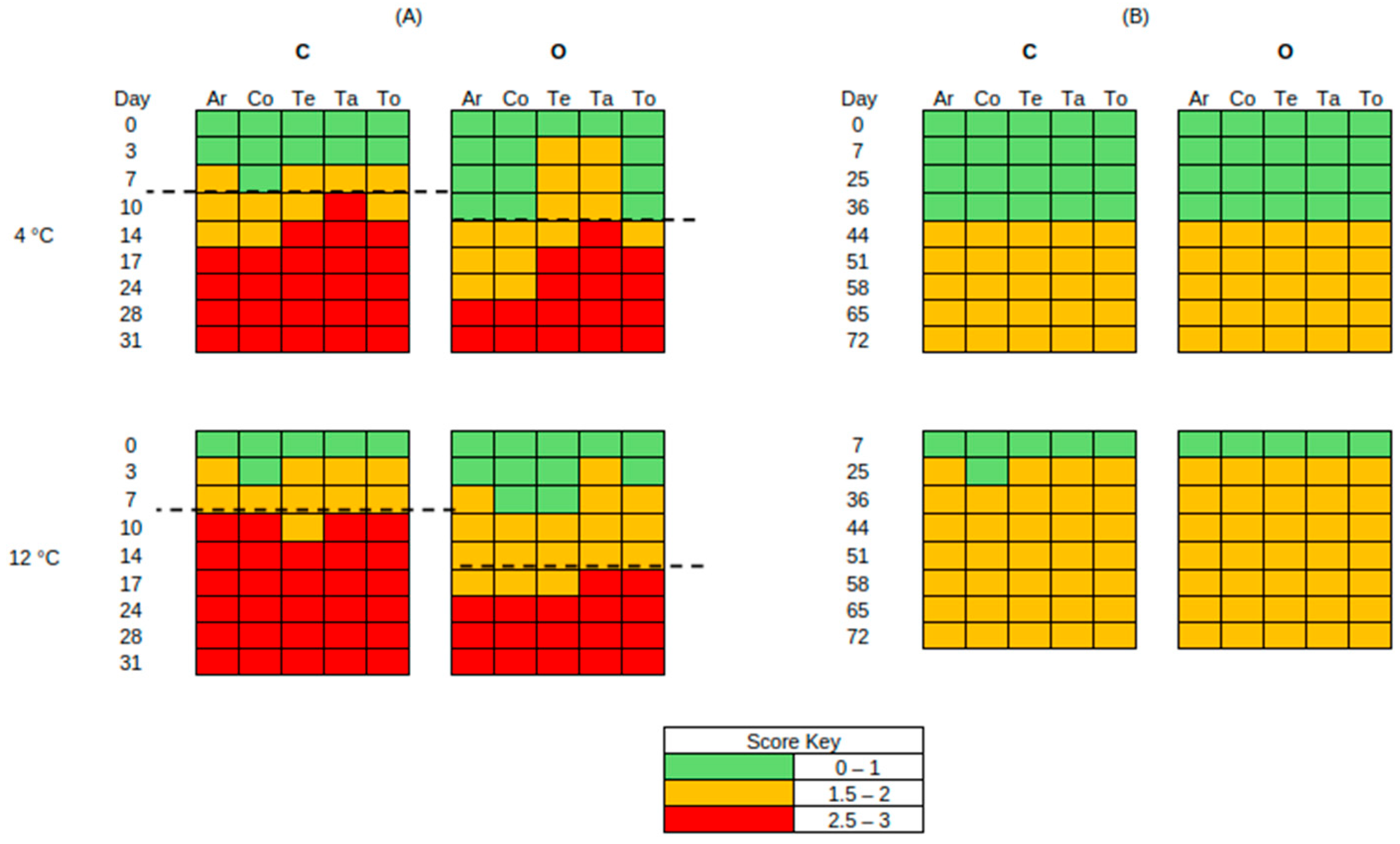

3.2. Sensory Analysis

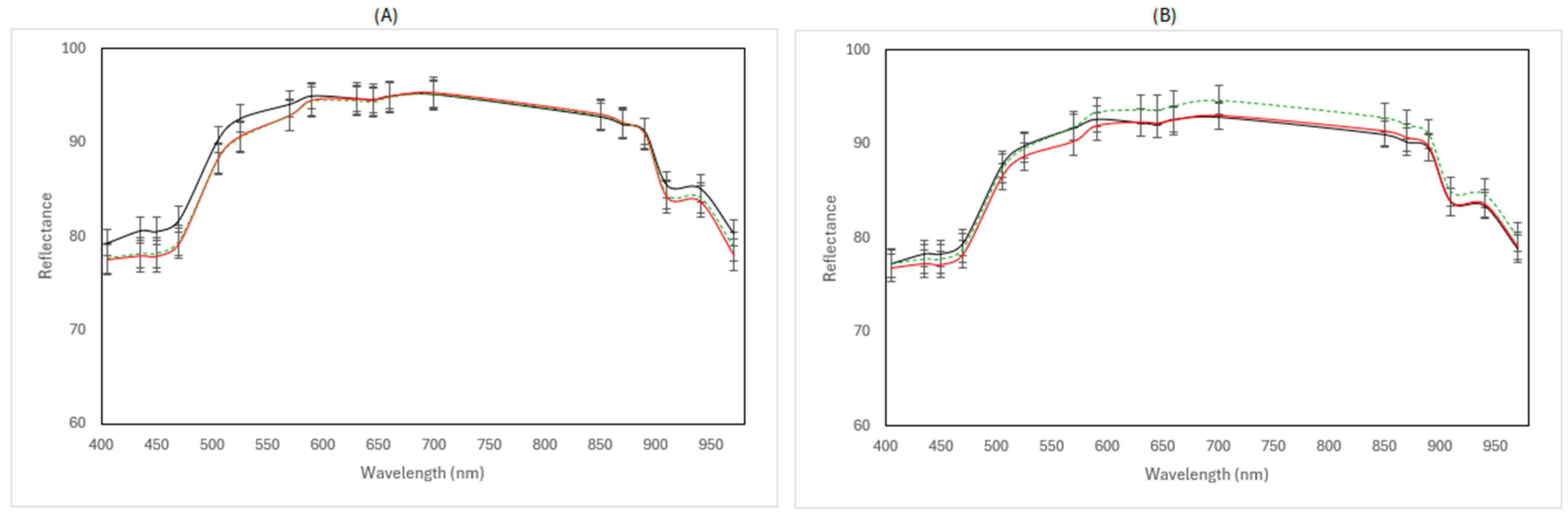

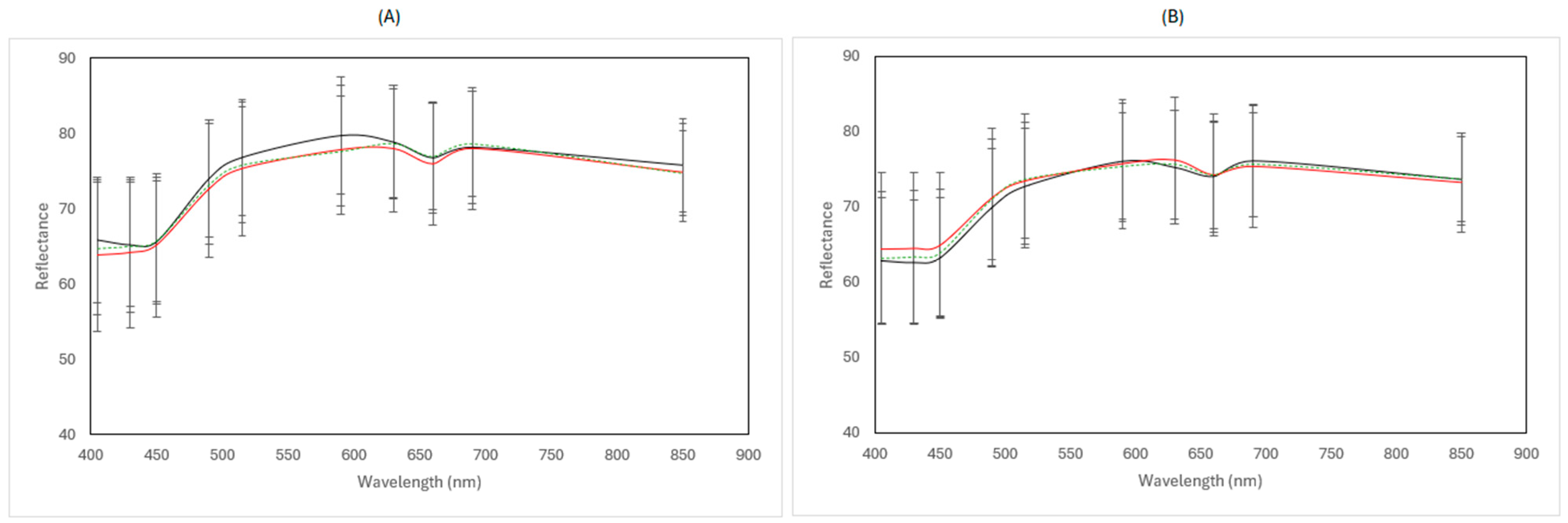

3.3. Multispectral Imaging Data

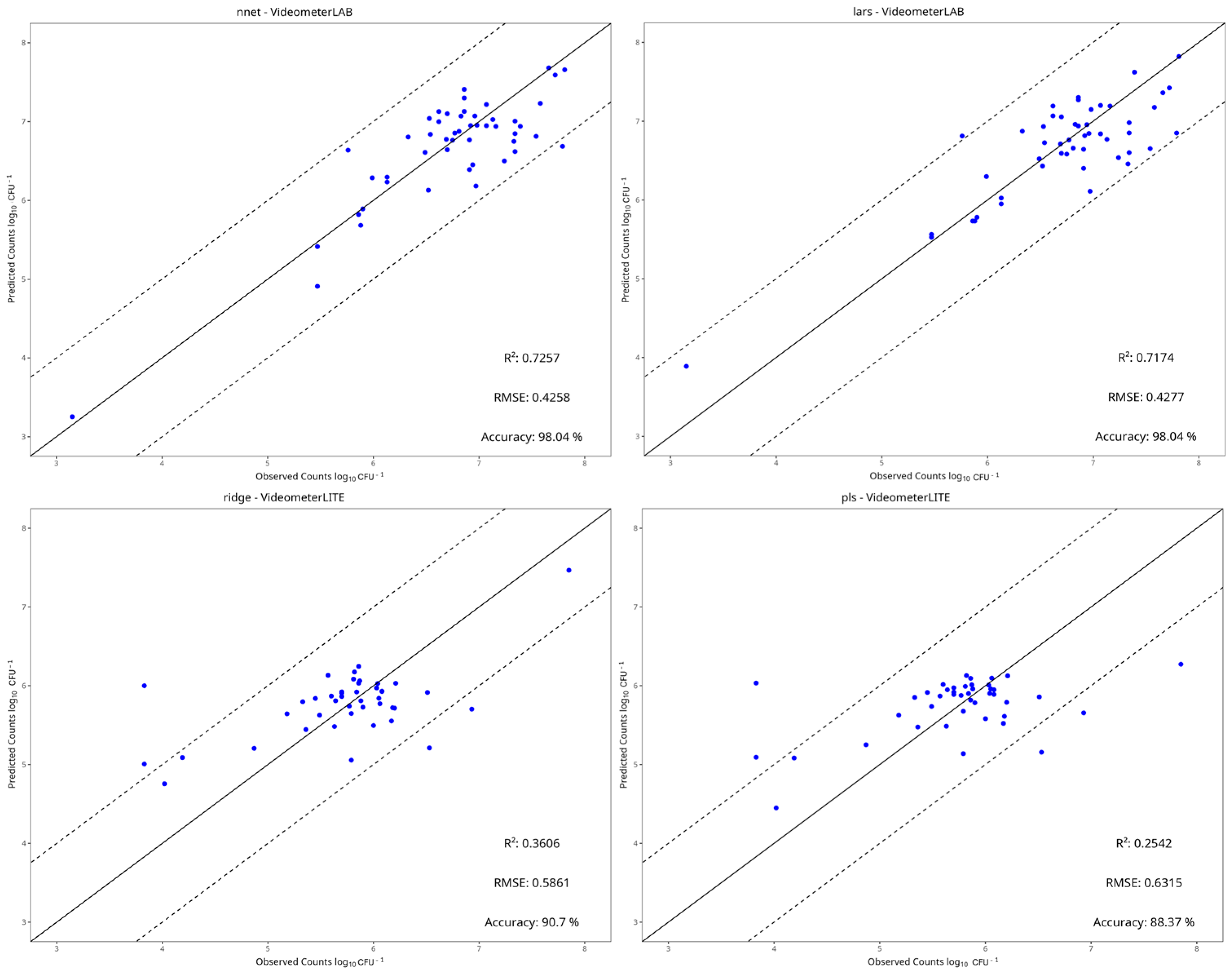

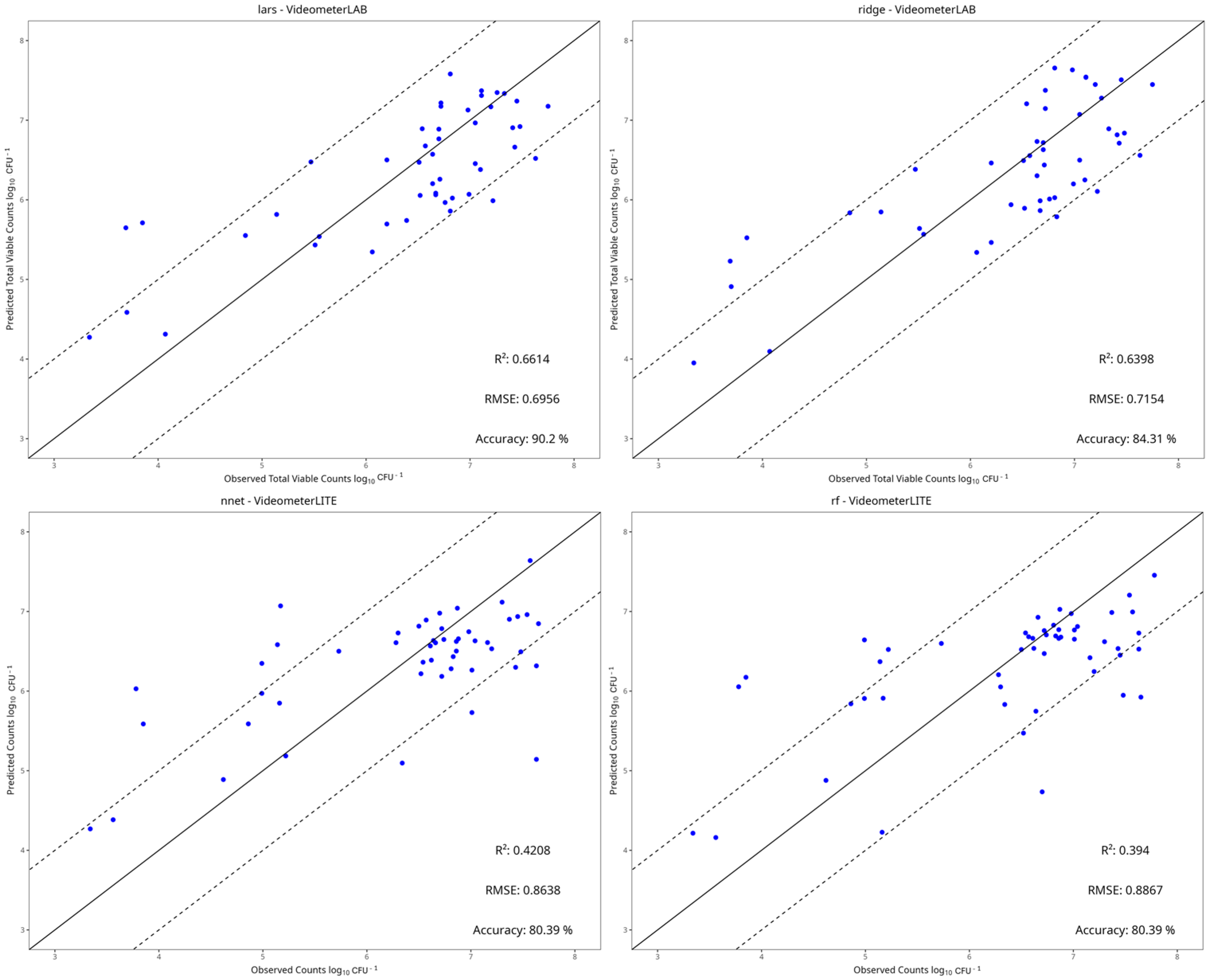

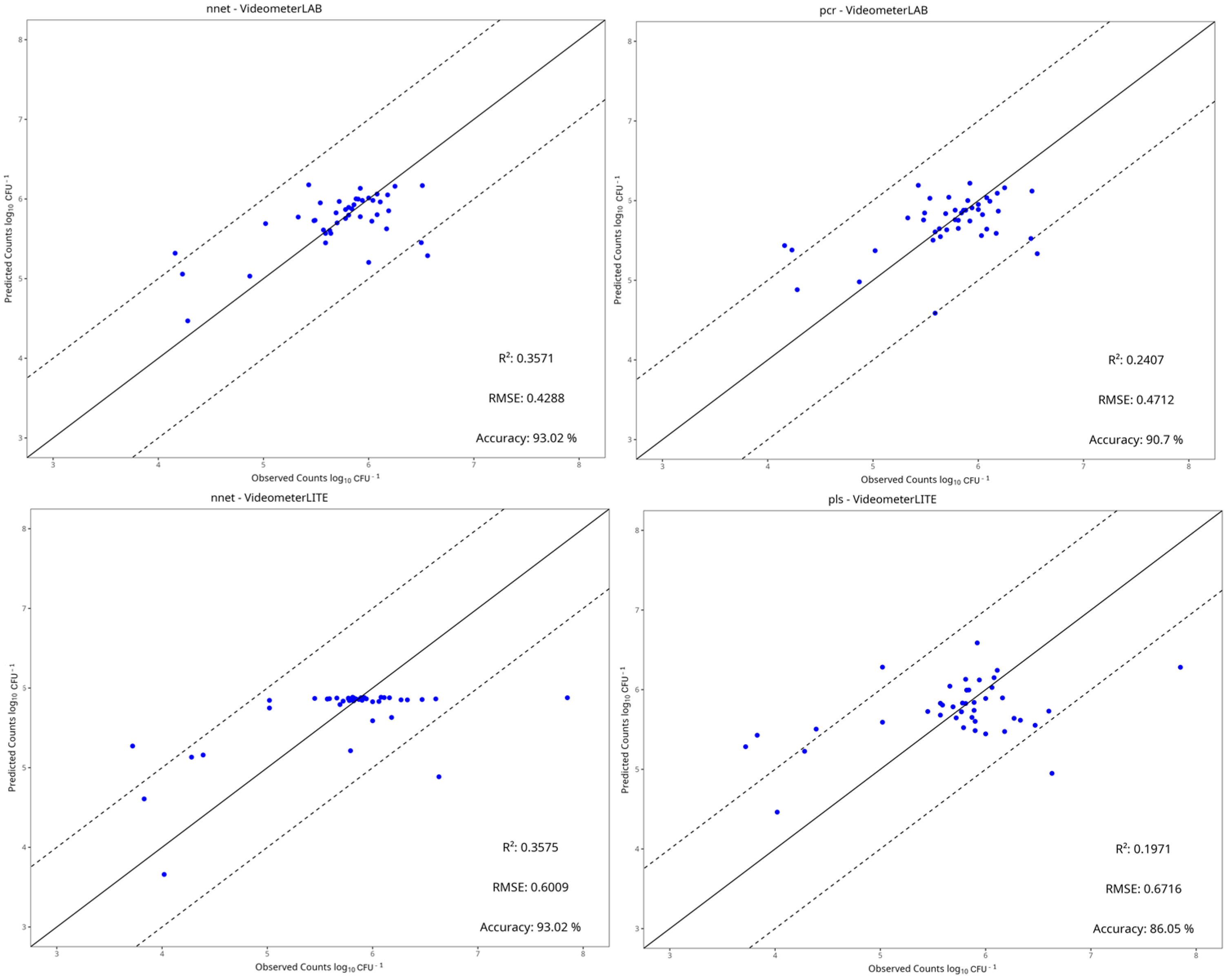

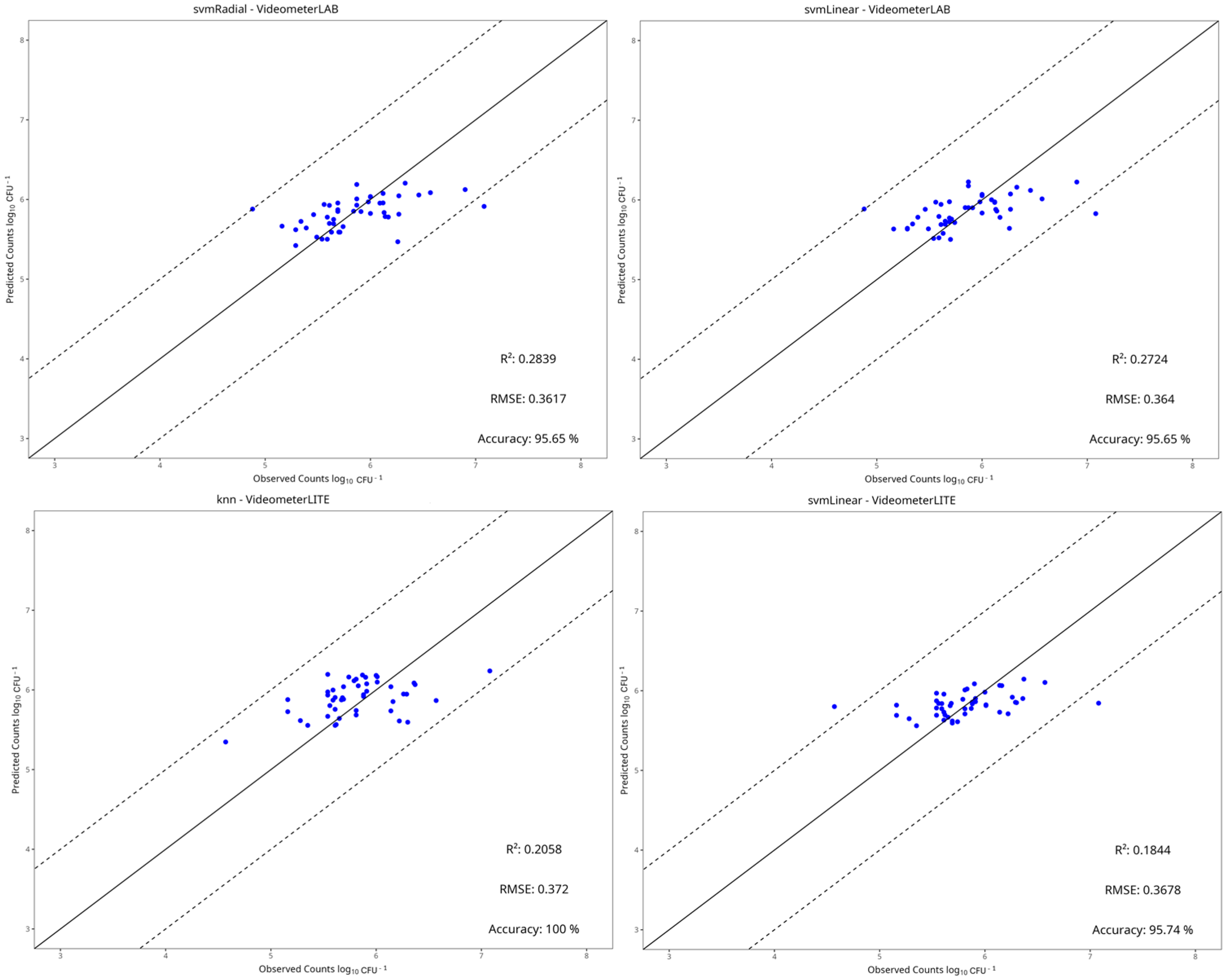

3.4. Machine Learning Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EO | Essential Oil |

| LAB | Lactic Acid Bacteria |

| TVC | Total Viable Counts |

| MSI | Multispectral Imaging |

| C | Control Samples with Na-alginate edible films |

| O | Samples with oregano EO in the Na-alginate edible films |

| CE | Control Na-alginate edible films samples inoculated with E. coli O157:H7 |

| CL | Control Na-alginate edible films samples inoculated with Listeria monocytogenes |

| OE | Na-alginate edible films with oregano EO samples inoculated with E. coli O157:H7 |

| OL | Na-alginate edible films with oregano EO samples inoculated with Listeria monocytogenes |

| SNV | Standard Normal Variate |

| PLSR | Partial Least Squares Regression |

| PCR | Principal Component Regression |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines Regression |

| kNN | k-Nearest Neighbours Regression |

| NNet | Neural Network Regression |

| LARs | Least Angle Regression |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

References

- Tzora, A.; Nelli, A.; Voidarou, C.; Fthenakis, G.; Rozos, G.; Theodorides, G.; Bonos, E.; Skoufos, I. Microbiota “Fingerprint” of Greek Feta Cheese through Ripening. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsouri, E.; Magriplis, E.; Zampelas, A.; Nychas, G.-J.; Drosinos, E.H. Nutritional Characteristics of Prepacked Feta PDO Cheese Products in Greece: Assessment of Dietary Intakes and Nutritional Profiles. Foods 2020, 9, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation (EC) No 1829/2002; Amending the Annex to Regulation (EC) No 1107/96 with Regard to the Name ‘Feta’ 2002. EUR-Lex: Luxembourg, 2002.

- Georgalaki, M.; Anastasiou, R.; Zoumpopoulou, G.; Charmpi, C.; Lazaropoulos, G.; Bounenni, R.; Papadimitriou, K.; Tsakalidou, E. Feta Cheese: A Pool of Non-Starter Lactic Acid Bacteria (NSLAB) with Anti-Hypertensive Potential. Int. Dairy J. 2025, 162, 106144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, P.; Konteles, S.; Batrinou, A.; Ouzounis, S.; Tsironi, T.; Halvatsiotis, P.; Tsakali, E.; Van Impe, J.F.M.; Vougiouklaki, D.; Strati, I.F.; et al. Characterization of Bacterial Microbiota of P.D.O. Feta Cheese by 16S Metagenomic Analysis. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolopoulou, E.; Sarantinopoulos, P.; Zoidou, E.; Aktypis, A.; Moschopoulou, E.; Kandarakis, I.G.; Anifantakis, E.M. Evolution of Microbial Populations during Traditional Feta Cheese Manufacture and Ripening. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 82, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrelli, E.; Stamatiou, A.; Tassou, C.; Nychas, G.-J.; Doulgeraki, A. Microbiological and Metagenomic Analysis to Assess the Effect of Container Material on the Microbiota of Feta Cheese during Ripening. Fermentation 2020, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayaloglu, A.A. Cheese Varieties Ripened Under Brine. In Cheese; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 997–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronikou, A.; Larsen, N.; Lillevang, S.K.; Jespersen, L. Occurrence and Identification of Yeasts in Production of White-Brined Cheese. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salustiano, V.C.; Andrade, N.J.; Brandão, S.C.C.; Azeredo, R.M.C.; Lima, S.A.K. Microbiological Air Quality of Processing Areas in a Dairy Plant as Evaluated by the Sedimentation Technique and a One-Stage Air Sampler. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2003, 34, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, K.; Nath, L.S. Studies on the Air Quality in a Dairy Processing Plant. Indian J. Vet. Anim. Sci. Res. 2014, 43, 346–353. [Google Scholar]

- Kousta, M.; Mataragas, M.; Skandamis, P.; Drosinos, E.H. Prevalence and Sources of Cheese Contamination with Pathogens at Farm and Processing Levels. Food Control 2010, 21, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.J.; Maciel, L.C.; Teixeira, J.A.; Vicente, A.A.; Cerqueira, M.A. Use of Edible Films and Coatings in Cheese Preservation: Opportunities and Challenges. Food Res. Int. 2018, 107, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bintsis, T.; Papademas, P. Microbiological Quality of White-Brined Cheeses: A Review. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2002, 55, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, K.; Anastasiou, R.; Georgalaki, M.; Bounenni, R.; Paximadaki, A.; Charmpi, C.; Alexandraki, V.; Kazou, M.; Tsakalidou, E. Comparison of the Microbiome of Artisanal Homemade and Industrial Feta Cheese through Amplicon Sequencing and Shotgun Metagenomics. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraiva, C.; Silva, A.C.; García-Díez, J.; Cenci-Goga, B.; Grispoldi, L.; Silva, A.F.; Almeida, J.M. Antimicrobial Activity of Myrtus communis L. and Rosmarinus officinalis L. Essential Oils against Listeria monocytogenes in Cheese. Foods 2021, 10, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapetanakou, A.E.; Gkerekou, M.A.; Vitzilaiou, E.S.; Skandamis, P.N. Assessing the Capacity of Growth, Survival, and Acid Adaptive Response of Listeria monocytogenes during Storage of Various Cheeses and Subsequent Simulated Gastric Digestion. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 246, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, J.; Andrew, P.W.; Faleiro, M.L. Listeria monocytogenes in Cheese and the Dairy Environment Remains a Food Safety Challenge: The Role of Stress Responses. Food Res. Int. 2015, 67, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schvartzman, M.S.; Maffre, A.; Tenenhaus-Aziza, F.; Sanaa, M.; Butler, F.; Jordan, K. Modelling the Fate of Listeria monocytogenes during Manufacture and Ripening of Smeared Cheese Made with Pasteurised or Raw Milk. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 145, S31–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Sánchez, L.A.; Van Tassell, M.L.; Miller, M.J. Invited Review: Hispanic-Style Cheeses and Their Association with Listeria monocytogenes. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 2421–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarruel-López, A.; Castro Rosas, J.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Nuño, K.; Torres-Vitela, R.T.; Martínez-Gonzáles, N.; Garay-Martínez, L.E. Indicator Microorganisms, Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcal Enterotoxin, and Physicochemical Parameters in Requeson Cheese. Afr. J. Food Sci. 2016, 10, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christaki, S.; Moschakis, T.; Kyriakoudi, A.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Mourtzinos, I. Recent Advances in Plant Essential Oils and Extracts: Delivery Systems and Potential Uses as Preservatives and Antioxidants in Cheese. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P.; Marin, J.M. Occurrence of Non-O157 Shiga Toxin-Encoding Escherichia coli in Artisanal Mozzarella Cheese in Brazil: Risk Factor Associated with Food Workers. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 37, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, C.; Arliguie, C.; Montel, M.-C. Control of Shigatoxin-Producing Escherichia coli in Cheese by Dairy Bacterial Strains. Food Microbiol. 2016, 53, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, K.A.; Loeffelholz, J.M.; Ford, J.P.; Doyle, M.P. Fate of Escherichia Coli O157:H7 as Affected by pH or Sodium Chloride and in Fermented, Dry Sausage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 2513–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira, N.V.B.; Holley, R.A.; Bordin, K.; de Macedo, R.E.F.; Luciano, F.B. Combination of Essential Oil Compounds and Phenolic Acids against Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Vitro and in Dry-Fermented Sausage Production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 260, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dineen, S.S.; Takeuchi, K.; Soudah, J.E.; Boor, K.J. Persistence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Dairy Fermentation Systems. J. Food Prot. 1998, 61, 1602–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biji, K.B.; Ravishankar, C.N.; Mohan, C.O.; Srinivasa Gopal, T.K. Smart Packaging Systems for Food Applications: A Review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 6125–6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, C.; Kurek, M.; Hayouka, Z.; Röcker, B.; Yildirim, S.; Antunes, M.D.C.; Nilsen-Nygaard, J.; Pettersen, M.K.; Freire, C.S.R. A Concise Guide to Active Agents for Active Food Packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 80, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, H.S.; El-Sayed, S.M.; Mabrouk, A.M.M.; Nawwar, G.A.; Youssef, A.M. Development of Eco-Friendly Probiotic Edible Coatings Based on Chitosan, Alginate and Carboxymethyl Cellulose for Improving the Shelf Life of UF Soft Cheese. J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 29, 1941–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta-Kubica, A.; Jamróz, E.; Kawecka, A.; Juszczak, L.; Krzyściak, P. Active Edible Furcellaran/Whey Protein Films with Yerba Mate and White Tea Extracts: Preparation, Characterization and Its Application to Fresh Soft Rennet-Curd Cheese. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saputra, E.; Pramono, H.; Abdillah, A.A.; Alamsjah, M.A. An Edible Film Characteristic of Chitosan Made from Shrimp Waste as a Plasticizer. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 2015, 5, 128743. [Google Scholar]

- Kurt, A.; Toker, O.S.; Tornuk, F. Effect of Xanthan and Locust Bean Gum Synergistic Interaction on Characteristics of Biodegradable Edible Film. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 102, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wei, Z.; Xue, C. Alginate-based Delivery Systems for Food Bioactive Ingredients: An Overview of Recent Advances and Future Trends. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 5345–5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atarés, L.; Chiralt, A. Essential Oils as Additives in Biodegradable Films and Coatings for Active Food Packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 48, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgano, F.; Condelli, N.; Favati, F.; Di Bianco, V.; Perretti, G.; Caruso, M.C. Biodegradable Packaging and Edible Coating for Fresh-Cut Fruits and Vegetables. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2015, 27, 1A. [Google Scholar]

- de Campos, A.C.L.P.; Saldanha Nandi, R.D.; Scandorieiro, S.; Gonçalves, M.C.; Reis, G.F.; Dibo, M.; Medeiros, L.P.; Panagio, L.A.; Fagan, E.P.; Takayama Kobayashi, R.K.; et al. Antimicrobial Effect of Origanum vulgare (L.) Essential Oil as an Alternative for Conventional Additives in the Minas Cheese Manufacture. LWT 2022, 157, 113063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zantar, S.; Yedri, F.; Mrabet, R.; Laglaoui, A.; Bakkali, M.; Zerrouk, M.H. Effect of Thymus vulgaris and Origanum compactum Essential Oils on the Shelf Life of Fresh Goat Cheese. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2014, 26, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Embuena, A.I.; Cháfer Nácher, M.; Chiralt Boix, A.; Molina Pons, M.P.; Borrás Llopis, M.; Beltran Martínez, M.C.; González Martínez, C. Quality of Goat′s Milk Cheese as Affected by Coating with Edible Chitosan-Essential Oil Films. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2016, 70, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiga-Artigas, M.; Acevedo-Fani, A.; Martín-Belloso, O. Improving the Shelf Life of Low-Fat Cut Cheese Using Nanoemulsion-Based Edible Coatings Containing Oregano Essential Oil and Mandarin Fiber. Food Control 2017, 76, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogianni, V.G.; Kasapidou, E.; Mitlianga, P.; Mataragas, M.; Pappa, E.; Kondyli, E.; Bosnea, L. Production, Characteristics and Application of Whey Protein Films Activated with Rosemary and Sage Extract in Preserving Soft Cheese. LWT 2022, 155, 112996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharbach, M.; Alaoui Mansouri, M.; Taabouz, M.; Yu, H. Current Application of Advancing Spectroscopy Techniques in Food Analysis: Data Handling with Chemometric Approaches. Foods 2023, 12, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, J.; Ouyang, Q. Recent Advances in Emerging Imaging Techniques for Non-Destructive Detection of Food Quality and Safety. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2013, 52, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrocka, A.; Lamorska, J. Determination of Food Quality by Using Spectroscopic Methods. In Advances in Agrophysical Research; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lytou, A.; Fengou, L.-C.; Koukourikos, A.; Karampiperis, P.; Zervas, P.; Schultz Carstensen, A.; Del Genio, A.; Michael Carstensen, J.; Schultz, N.; Chorianopoulos, N.; et al. Seabream Quality Monitoring throughout the Supply Chain Using a Portable Multispectral Imaging Device. J. Food Prot. 2024, 87, 100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthou, E.; Karnavas, A.; Fengou, L.-C.; Bakali, A.; Lianou, A.; Tsakanikas, P.; Nychas, G.-J.E. Spectroscopy and Imaging Technologies Coupled with Machine Learning for the Assessment of the Microbiological Spoilage Associated to Ready-to-Eat Leafy Vegetables. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 361, 109458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengou, L.-C.; Lytou, A.; Tsekos, G.; Tsakanikas, P.; Nychas, G.-J.E. Features in visible and Fourier transform infrared spectra confronting aspects of meat quality and fraud. Food Chem. 2024, 440, 138184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, J.M.; Hansen, M.E.; Lassen, N.K.; Allé, L. Creating Surface Chemistry Maps Using Multispectral Vision Technology. In Proceedings of the MICCAI (Medical Image Computing and Computer Aided Intervention) 2006 Workshop on Biophotonics Imaging, Copenhagen, Denmark, 1–6 October 2006; pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pavli, F.; Kovaiou, I.; Apostolakopoulou, G.; Kapetanakou, A.; Skandamis, P.; Nychas, G.-J.; Tassou, C.; Chorianopoulos, N. Alginate-Based Edible Films Delivering Probiotic Bacteria to Sliced Ham Pretreated with High Pressure Processing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, O.S.; Argyri, A.A.; Varzakis, E.E.; Tassou, C.C.; Chorianopoulos, N.G. Greek Functional Feta Cheese: Enhancing Quality and Safety Using a Lactobacillus plantarum Strain with Probiotic Potential. Food Microbiol. 2018, 74, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulou, O.; Panagou, E.Z.; Tassou, C.C.; Nychas, G.-J.E. Contribution of Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy Data on the Quantitative Determination of Minced Pork Meat Spoilage. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 3264–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukaki, A.; Papadopoulou, O.S.; Tzavara, C.; Mantzara, A.-M.; Michopoulou, K.; Tassou, C.; Skandamis, P.; Nychas, G.-J.; Chorianopoulos, N. Monitoring the Bioprotective Potential of Lactiplantibacillus pentosus Culture on Pathogen Survival and the Shelf-Life of Fresh Ready-to-Eat Salads Stored under Modified Atmosphere Packaging. Pathogens 2024, 13, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagou, E.Z.; Papadopoulou, O.; Carstensen, J.M.; Nychas, G.-J.E. Potential of Multispectral Imaging Technology for Rapid and Non-Destructive Determination of the Microbiological Quality of Beef Filets during Aerobic Storage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 174, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estelles-Lopez, L.; Ropodi, A.; Pavlidis, D.; Fotopoulou, J.; Gkousari, C.; Peyrodie, A.; Panagou, E.; Nychas, G.-J.; Mohareb, F. An Automated Ranking Platform for Machine Learning Regression Models for Meat Spoilage Prediction Using Multi-Spectral Imaging and Metabolic Profiling. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohareb, F.; Papadopoulou, O.; Panagou, E.; Nychas, G.-J.; Bessant, C. Ensemble-Based Support Vector Machine Classifiers as an Efficient Tool for Quality Assessment of Beef Fillets from Electronic Nose Data. Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 3711–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; Posit: Boston, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ahari, H.; Soufiani, S.P. Smart and Active Food Packaging: Insights in Novel Food Packaging. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 12, 657233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaraw, P.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Verma, A.K.; Barba, F.J.; Singh, V.P.; Kumar, P.; Lorenzo, J.M. Edible Films/Coating with Tailored Properties for Active Packaging of Meat, Fish and Derived Products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 98, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Shah, Y.A.; Jawad, M.; Al-Azri, M.S.; Ullah, S.; Anwer, M.K.; Aldawsari, M.F.; Koca, E.; Aydemir, L.Y. The Effect of Sage (Salvia sclarea) Essential Oil on the Physiochemical and Antioxidant Properties of Sodium Alginate and Casein-Based Composite Edible Films. Gels 2023, 9, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarinou, C.S.; Papadopoulou, O.S.; Doulgeraki, A.I.; Tassou, C.C.; Galanis, A.; Chorianopoulos, N.; Argyri, A.A. Application of Multi-Functional Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains in a Pilot Scale Feta Cheese Production. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1254598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcial, G.E.; Gerez, C.L.; de Kairuz, M.N.; Araoz, V.C.; Schuff, C.; de Valdez, G.F. Influence of Oregano Essential Oil on Traditional Argentinean Cheese Elaboration: Effect on Lactic Starter Cultures. Rev. Argent. De Microbiol. 2016, 48, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, R.J.; de Souza, G.T.; Honório, V.G.; de Sousa, J.P.; da Conceição, M.L.; Maganani, M.; de Souza, E.L. Comparative Inhibitory Effects of Thymus vulgaris L. Essential Oil against Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes and Mesophilic Starter Co-Culture in Cheese-Mimicking Models. Food Microbiol. 2015, 52, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, A.; Librán, C.M.; Berruga, M.I.; Carmona, M.; Zalacain, A. Dairy Matrix Effect on the Transference of Rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis) Essential Oil Compounds during Cheese Making. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 95, 1507–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atanassova, M.R.; Fernández-Otero, C.; Rodríguez-Alonso, P.; Fernández-No, I.C.; Garabal, J.I.; Centeno, J.A. Characterization of Yeasts Isolated from Artisanal Short-Ripened Cows’ Cheeses Produced in Galicia (NW Spain). Food Microbiol. 2016, 53, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshidian, N.; Yousefi, M.; Khanniri, E.; Mortazavian, A.M. Potential Application of Essential Oils as Antimicrobial Preservatives in Cheese. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 45, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osimani, A.; Garofalo, C.; Harasym, J.; Aquilanti, L. Use of Essential Oils against Foodborne Spoilage Yeasts: Advantages and Drawbacks. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 45, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S. Essential Oils: Their Antibacterial Properties and Potential Applications in Foods—A Review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, H.S.; El-Sayed, S.M. A Modern Trend to Preserve White Soft Cheese Using Nano-Emulsified Solutions Containing Cumin Essential Oil. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2021, 16, 100499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.P.; Devkota, H.P.; Nigam, M.; Adetunji, C.O.; Srivastava, N.; Saklani, S.; Shukla, I.; Azmi, L.; Shariati, M.A.; Melo Coutinho, H.D.; et al. Combination of Essential Oils in Dairy Products: A Review of Their Functions and Potential Benefits. LWT 2020, 133, 110116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvea, F.D.S.; Rosenthal, A.; Ferreira, E.H.D.R. Plant Extract and Essential Oils Added as Antimicrobials to Cheeses: A Review. Ciência Rural 2017, 47, e20160908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govaris, A.; Papageorgiou, D.K.; Papatheodorou, K. Behavior of Escherichia coli O157:H7 during the Manufacture and Ripening of Feta and Telemes Cheeses. J. Food Prot. 2002, 65, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgari, K.; Hatzikamari, M.; Delepoglou, A.; Georgakopoulos, P.; Litopoulou-Tzanetaki, E.; Tzanetakis, N. Antifungal Activity of Non-Starter Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolates from Dairy Products. Food Control 2010, 21, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scollard, J.; Francis, G.A.; O’beirne, D. Effects of Essential Oil Treatment, Gas Atmosphere, and Storage Temperature on Listeria monocytogenes in a Model Vegetable System. J. Food Prot. 2009, 72, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motelica, L.; Ficai, D.; Oprea, O.; Ficai, A.; Trusca, R.-D.; Andronescu, E.; Holban, A.M. Biodegradable Alginate Films with ZnO Nanoparticles and Citronella Essential Oil—A Novel Antimicrobial Structure. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govaris, A.; Botsoglou, E.; Sergelidis, D.; Chatzopoulou, P.S. Antibacterial Activity of Oregano and Thyme Essential Oils against Listeria monocytogenes and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Feta Cheese Packaged under Modified Atmosphere. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 1240–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, L.I.; Ibrahim, N.; Abdel-Salam, A.B.; Fahim, K.M. Potential Application of Ginger, Clove and Thyme Essential Oils to Improve Soft Cheese Microbial Safety and Sensory Characteristics. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritota, M.; Manzi, P. Natural Preservatives from Plant in Cheese Making. Animals 2020, 10, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benassila, S.; Boussif, K.; El Hizazi, S.; Mamouni, R.; Achemchem, F. Effects of Oregano and Rosemary Essential Oils on the Physicochemical, Microbiological and Organoleptic Characteristics of Fresh Cheese. Food Humanit. 2025, 4, 100609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucimar, M.; Moreira, L.; Madruga, M.S.; Rodríguez-Pulido, F.J.; Heredia, F.J.; Barbin, D.F. Comparison of Hyperspectral Imaging and Spectrometers for Prediction of Cheeses Composition. Food Res. Int. 2024, 183, 114242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stocco, G.; Gómez-Mascaraque, L.G.; Kr Deshwal, G.; Sanchez, J.C.; Molle, A.; Pizzamiglio, V.; Berzaghi, P.; Gergov, G.; Cipolat-Gotet, C. Exploring the Use of NIR and Raman Spectroscopy for the Prediction of Quality Traits in PDO Cheeses. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1327301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, L.; Koureas, M.; Pappas, C.S.; Manouras, A.; Kantas, D.; Malissiova, E. Chemometric Classification of Feta Cheese Authenticity via ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuelian, C.L.; Ghetti, M.; Lorenzi, C.D.; Pozza, M.; Franzoi, M.; Marchi, M.D. Feasibility of Pocket-Sized Near-Infrared Spectrometer for the Prediction of Cheese Quality Traits. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 105, 104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVey, C.; Elliott, C.T.; Cannavan, A.; Kelly, S.D.; Petchkongkaew, A.; Haughey, S.A. Portable Spectroscopy for High Throughput Food Authenticity Screening: Advancements in Technology and Integration into Digital Traceability Systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curto, B.; Moreno, V.; García-Esteban, J.A.; Blanco, F.J.; González, I.; Vivar, A.; Revilla, I. Accurate Prediction of Sensory Attributes of Cheese Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Based on Artificial Neural Network. Sensors 2020, 20, 3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisak Jakopović, K.; Barukčić Jurina, I.; Marušić Radovčić, N.; Božanić, R.; Jurinjak Tušek, A. Reduced Sodium in White Brined Cheese Production: Artificial Neural Network Modeling for the Prediction of Specific Properties of Brine and Cheese during Storage. Fermentation 2023, 9, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Storage Temperature | Packaging Conditions | Treatment | Abbreviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 °C/12 °C | Aerobic/Vacuum | Non- inoculated | Control edible films | C |

| Edible films with oregano EO | O | |||

| Pathogen inoculated | Control edible films with E. coli O157:H7 or L. monocytogenes | CE or CL, respectively | ||

| Edible films with oregano EO and E. coli O157:H7 or L. monocytogenes | OE or OL, respectively | |||

| Instrument | Preprocessing | Model | RMSE | MAE | R2 | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchtop-MSI | Centring and Scaling | PLS-R | 0.431 | 0.333 | 0.717 | 0.96 |

| Ridge | 0.447 | 0.360 | 0.681 | 0.96 | ||

| SVM-Linear | 0.453 | 0.322 | 0.673 | 0.96 | ||

| SVM-Radial | 0.487 | 0.371 | 0.622 | 0.96 | ||

| Random Forest | 0.598 | 0.462 | 0.431 | 0.92 | ||

| kNN | 0.600 | 0.469 | 0.426 | 0.88 | ||

| PCR | 0.451 | 0.344 | 0.676 | 0.92 | ||

| LARS | 0.428 | 0.327 | 0.717 | 0.98 | ||

| NNet | 0.426 | 0.328 | 0.726 | 0.98 | ||

| Portable-MSI | Centring and Scaling | PLS-R | 0.632 | 0.429 | 0.254 | 0.88 |

| Ridge | 0.586 | 0.415 | 0.361 | 0.91 | ||

| SVM-Linear | 0.655 | 0.431 | 0.197 | 0.88 | ||

| SVM-Radial | 0.707 | 0.436 | 0.063 | 0.86 | ||

| Random Forest | 0.650 | 0.411 | 0.207 | 0.88 | ||

| kNN | 0.716 | 0.449 | 0.039 | 0.86 | ||

| PCR | 0.634 | 0.441 | 0.249 | 0.88 | ||

| LARS | 0.643 | 0.427 | 0.225 | 0.86 | ||

| NNet | 0.655 | 0.436 | 0.196 | 0.88 |

| Instrument | Preprocessing | Model | RMSE | MAE | R2 | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchtop-MSI | SNV | PLS-R | 0.741 | 0.601 | 0.609 | 0.84 |

| Ridge | 0.715 | 0.586 | 0.640 | 0.84 | ||

| SVM-Linear | 0.721 | 0.571 | 0.636 | 0.88 | ||

| SVM-Radial | 0.928 | 0.711 | 0.386 | 0.73 | ||

| Random Forest | 0.903 | 0.665 | 0.419 | 0.69 | ||

| kNN | 1.345 | 0.895 | −0.290 | 0.67 | ||

| PCR | 0.849 | 0.659 | 0.487 | 0.71 | ||

| LARS | 0.696 | 0.555 | 0.661 | 0.90 | ||

| NNet | 0.827 | 0.624 | 0.513 | 0.80 | ||

| Portable-MSI | Centring and Scaling | PLS-R | 1.013 | 0.842 | 0.203 | 0.67 |

| Ridge | 1.039 | 0.849 | 0.162 | 0.69 | ||

| SVM-Linear | 1.003 | 0.748 | 0.219 | 0.71 | ||

| SVM-Radial | 0.890 | 0.682 | 0.385 | 0.71 | ||

| Random Forest | 0.887 | 0.658 | 0.394 | 0.80 | ||

| kNN | 0.906 | 0.694 | 0.362 | 0.75 | ||

| PCR | 0.949 | 0.760 | 0.301 | 0.75 | ||

| LARS | 1.028 | 0.839 | 0.179 | 0.69 | ||

| NNet | 0.864 | 0.648 | 0.421 | 0.80 |

| Instrument | Preprocessing | Model | RMSE | MAE | R2 | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchtop-MSI | Centring and Scaling | PLS-R | 0.481 | 0.312 | 0.188 | 0.93 |

| Ridge | 0.609 | 0.346 | −0.300 | 0.88 | ||

| SVM-Linear | 0.485 | 0.314 | 0.173 | 0.93 | ||

| SVM-Radial | 0.492 | 0.323 | 0.152 | 0.95 | ||

| Random Forest | 0.559 | 0.361 | −0.098 | 0.95 | ||

| kNN | 0.562 | 0.392 | −0.108 | 0.88 | ||

| PCR | 0.471 | 0.317 | 0.221 | 0.91 | ||

| LARS | 0.530 | 0.327 | 0.015 | 0.88 | ||

| NNet | 0.429 | 0.281 | 0.360 | 0.93 | ||

| Portable-MSI | None | PLS-R | 0.672 | 0.474 | 0.197 | 0.86 |

| Ridge | 0.684 | 0.510 | 0.165 | 0.84 | ||

| SVM-Linear | 0.687 | 0.483 | 0.157 | 0.84 | ||

| SVM-Radial | 0.721 | 0.463 | 0.072 | 0.84 | ||

| Random Forest | 0.692 | 0.442 | 0.145 | 0.84 | ||

| kNN | 0.702 | 0.450 | 0.120 | 0.84 | ||

| PCR | 0.673 | 0.474 | 0.190 | 0.86 | ||

| LARS | 0.687 | 0.463 | 0.155 | 0.86 | ||

| NNet | 0.601 | 0.393 | 0.356 | 0.93 |

| Instrument | Preprocessing | Model | RMSE | MAE | R2 | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchtop-MSI | Centring and Scaling | PLS-R | 0.389 | 0.315 | 0.161 | 0.98 |

| Ridge | 0.452 | 0.340 | −0.130 | 0.96 | ||

| SVM-Linear | 0.364 | 0.261 | 0.272 | 0.96 | ||

| SVM-Radial | 0.362 | 0.257 | 0.284 | 0.96 | ||

| Random Forest | 0.389 | 0.293 | 0.161 | 0.96 | ||

| kNN | 0.406 | 0.301 | 0.087 | 0.96 | ||

| PCR | 0.382 | 0.273 | 0.192 | 0.98 | ||

| LARS | 0.421 | 0.324 | 0.018 | 0.98 | ||

| NNet | 0.381 | 0.286 | 0.195 | 0.98 | ||

| Portable-MSI | None | PLS-R | 0.390 | 0.293 | 0.074 | 0.96 |

| Ridge | 0.380 | 0.300 | 0.122 | 0.98 | ||

| SVM-Linear | 0.368 | 0.259 | 0.184 | 0.96 | ||

| SVM-Radial | 0.389 | 0.285 | 0.079 | 0.96 | ||

| Random Forest | 0.395 | 0.299 | 0.051 | 0.96 | ||

| kNN | 0.372 | 0.307 | 0.206 | 0.96 | ||

| PCR | 0.390 | 0.290 | 0.073 | 0.96 | ||

| LARS | 0.394 | 0.289 | 0.056 | 0.96 | ||

| NNet | 0.375 | 0.281 | 0.143 | 0.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Doukaki, A.; Frantzi, A.; Xenou, S.; Schoina, F.; Katsimperi, G.; Nychas, G.-J.; Chorianopoulos, N. Antimicrobial Effect of Oregano Essential Oil in Na-Alginate Edible Films for Shelf-Life Extension and Safety of Feta Cheese. Pathogens 2026, 15, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010065

Doukaki A, Frantzi A, Xenou S, Schoina F, Katsimperi G, Nychas G-J, Chorianopoulos N. Antimicrobial Effect of Oregano Essential Oil in Na-Alginate Edible Films for Shelf-Life Extension and Safety of Feta Cheese. Pathogens. 2026; 15(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010065

Chicago/Turabian StyleDoukaki, Angeliki, Aikaterini Frantzi, Stamatina Xenou, Fotoula Schoina, Georgia Katsimperi, George-John Nychas, and Nikos Chorianopoulos. 2026. "Antimicrobial Effect of Oregano Essential Oil in Na-Alginate Edible Films for Shelf-Life Extension and Safety of Feta Cheese" Pathogens 15, no. 1: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010065

APA StyleDoukaki, A., Frantzi, A., Xenou, S., Schoina, F., Katsimperi, G., Nychas, G.-J., & Chorianopoulos, N. (2026). Antimicrobial Effect of Oregano Essential Oil in Na-Alginate Edible Films for Shelf-Life Extension and Safety of Feta Cheese. Pathogens, 15(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010065