1. Introduction

Echinococcus granulosus is a zoonotic cestode whose larval stage is the causative agent of cystic echinococcosis (CE), a severe parasitic disease affecting both livestock and humans [

1]. The parasite has a global distribution, with endemic foci predominantly located in the Northern Hemisphere, including extensive regions of Asia, Europe, and North America [

2,

3]. In these endemic areas, the annual human incidence of CE ranges from less than 1 to 200 cases per 100,000 individuals [

4]. This disease imposes a substantial burden on public health, accounting for an estimated global loss of 285,500 disability-adjusted life years annually (DALYs) [

5,

6]. China has an estimated 30 million livestock infected with CE and 7 million new annual infections, over 70% of which occur in sheep. These infections result in annual economic losses of approximately 1 billion CNY (RMB), primarily due to decreased body weight, reduced milk production, and deteriorated meat and wool quality [

7]. In response to its significant impact, the World Health Organization (WHO) has classified echinococcosis as a neglected tropical disease (NTD) [

8]. Since 2005, China has intensified its national echinococcosis control efforts through central government funding and policies, with the goal of controlling and eliminating the disease by 2030 [

8].

China is a highly endemic area for both alveolar echinococcosis (AE) and CE, with CE having a higher prevalence [

9]. The disease is hyperendemic in western and northwestern pastoral regions [

10]. Humans and livestock acquire

E. granulosus infection by ingesting eggs from environments contaminated by feces of infected definitive hosts (e.g., dogs) [

11]. Following ingestion, the released oncospheres form metacestode cysts in internal organs, primarily the liver (~90%) and lungs (~10%) [

11,

12]. The interconnected transmission cycle among animals, humans, and the environment underscores the importance of the One Health approach for effective control [

13].

Sheep husbandry constitutes a primary economic pillar in these pastoral areas. Despite their importance, the epidemiology of

E. granulosus infection in sheep remains poorly characterized, with existing studies being sporadic and geographically limited. Conducting continuous monitoring of

E. granulosus in sheep provides insights into the control status of echinococcosis in China. In Xinjiang, Guo et al. [

14,

15] reported infection rates of 3.5% (44/1270) in northern Xinjiang and 4.5% (131/2898) in the Altai region, identifying two genotypes (G1 and G3). A higher prevalence was reported by Lan et al. [

16], who found the prevalence of

E. granulosus in sheep in Xinjiang to be as high as 17.1% (58/340), and two genotypes (G1 and G3) were detected. A comparative serosurvey by Zhang et al. [

17] employing ELISA revealed a significantly higher seroprevalence in sheep from Qinghai Province than from Xinjiang. Similarly, an examination of cysts from slaughtered livestock by Su et al. [

18] found that 56.2% (41/73) of

E. granulosus cysts were from sheep and yaks, and genetic analysis detected three genotypes (sheep strains G1 and G3, and camel strain G6). Furthermore, Yang et al. [

19] demonstrated an age-associated increase in prevalence in sheep and goats in western Sichuan Province, from 38% in 1–6-year-olds to 70% in 10–12-year-olds, with only the G1 genotype identified in the region.

However, comprehensive epidemiological data on E. granulosus infection in sheep within Yili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture (Yili Prefecture) remain scarce. Since CE infections in sheep are predominantly asymptomatic and reliable antemortem diagnostic techniques are lacking, direct postmortem inspection of the liver represents a more accurate method for determining the true prevalence of the disease. Therefore, the objectives of this study were twofold: (i) to conduct the first comprehensive assessment of E. granulosus prevalence in slaughterhouse-sampled sheep from nine counties across Yili Prefecture between 2020 and 2024 and (ii) to genetically characterize the circulating strains of E. granulosus using morphological and molecular analyses. Our findings provide critical baseline data to inform and refine future CE control strategies in this highly endemic region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

This study was conducted in Yili Prefecture, located between 40°14′–49°10′ N and 80°09′–91°01′ E. The prefecture encompasses a total area of 56,500 km

2, which includes 47.26 million acres of grassland and 9.67 million acres of forest land, making it the largest pastoral region in Xinjiang. According to official government statistics, the total mutton production from 2020 to 2024 was 370,700 tons, with an annual average of 74,140 tons. Production ranged from 55,300 tons in 2020 to a peak of 81,700 tons in 2023. From 2022 to 2024, the sheep inventory was 6.4 million, 5.9 million, and 5.2 million, respectively, while the number of sheep slaughtered was 4.3 million, 4.6 million, and 4.4 million, respectively (

Supplementary Table S1).

2.2. Sample Collection and Visual Inspection

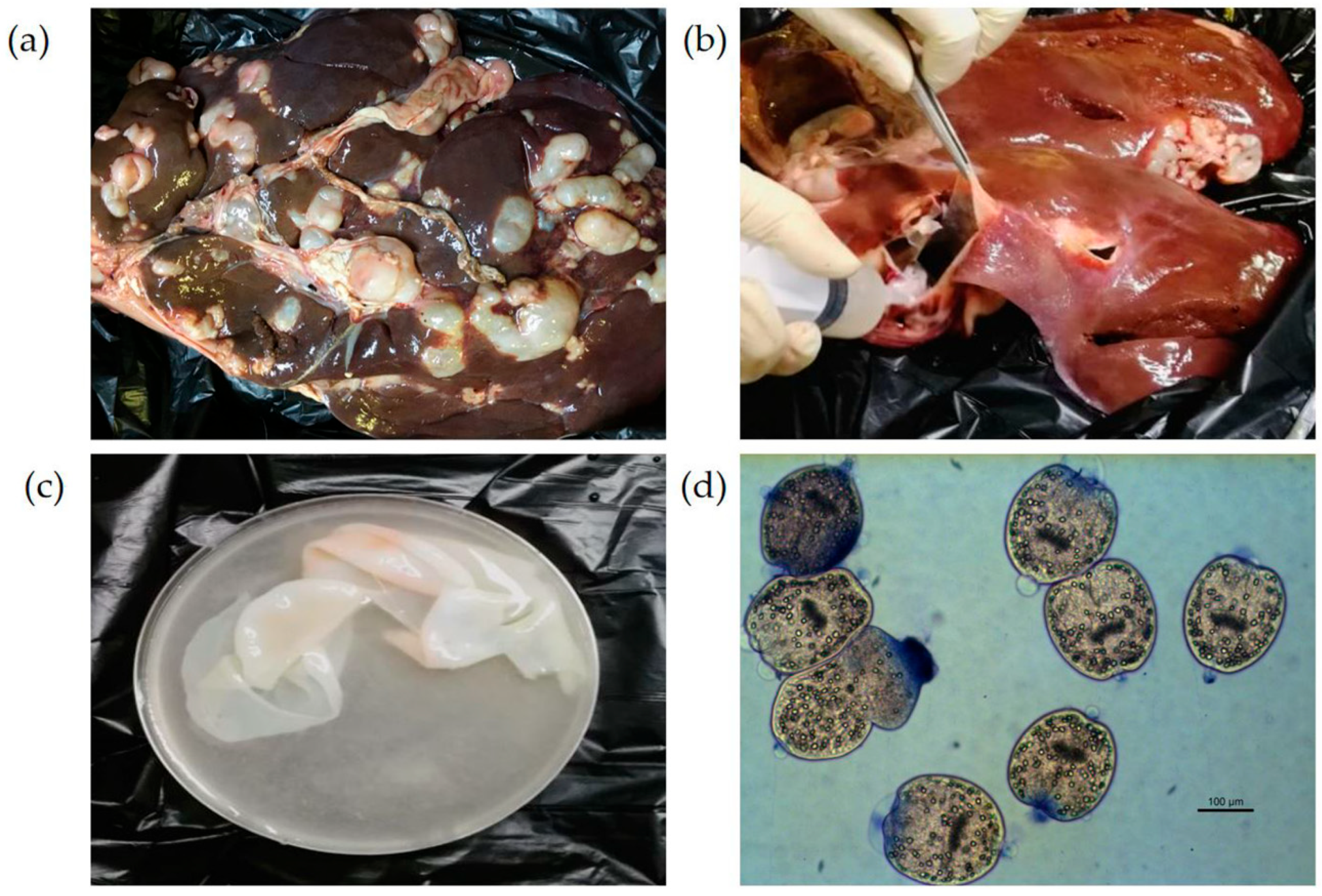

Sample collection was conducted uniformly across all counties in October each year. Inspections took place at slaughterhouses with a daily throughput exceeding 100 animals. Between fifty and eighty samples were inspected in each slaughterhouse, and the number of E. granulosus positive cases was recorded. Liver samples showing severe lesions-especially those with prominent surface cysts (including calcified cysts)-were transported to the laboratory for molecular testing.

During visual inspection, E. granulosus infection was diagnosed based on the presence of characteristic spherical cysts with thick, laminated, whitish walls and clear fluid or daughter cysts within. These features allow for a clear distinction from the biliary fibrosis and calcification caused by Fasciola hepatica and from the thin-walled, transparent vesicles attached to the hepatic surface caused by Cysticercus tenuicollis. Liver samples showing severe lesions (cysts larger than 5 cm) were transported to the laboratory for molecular testing.

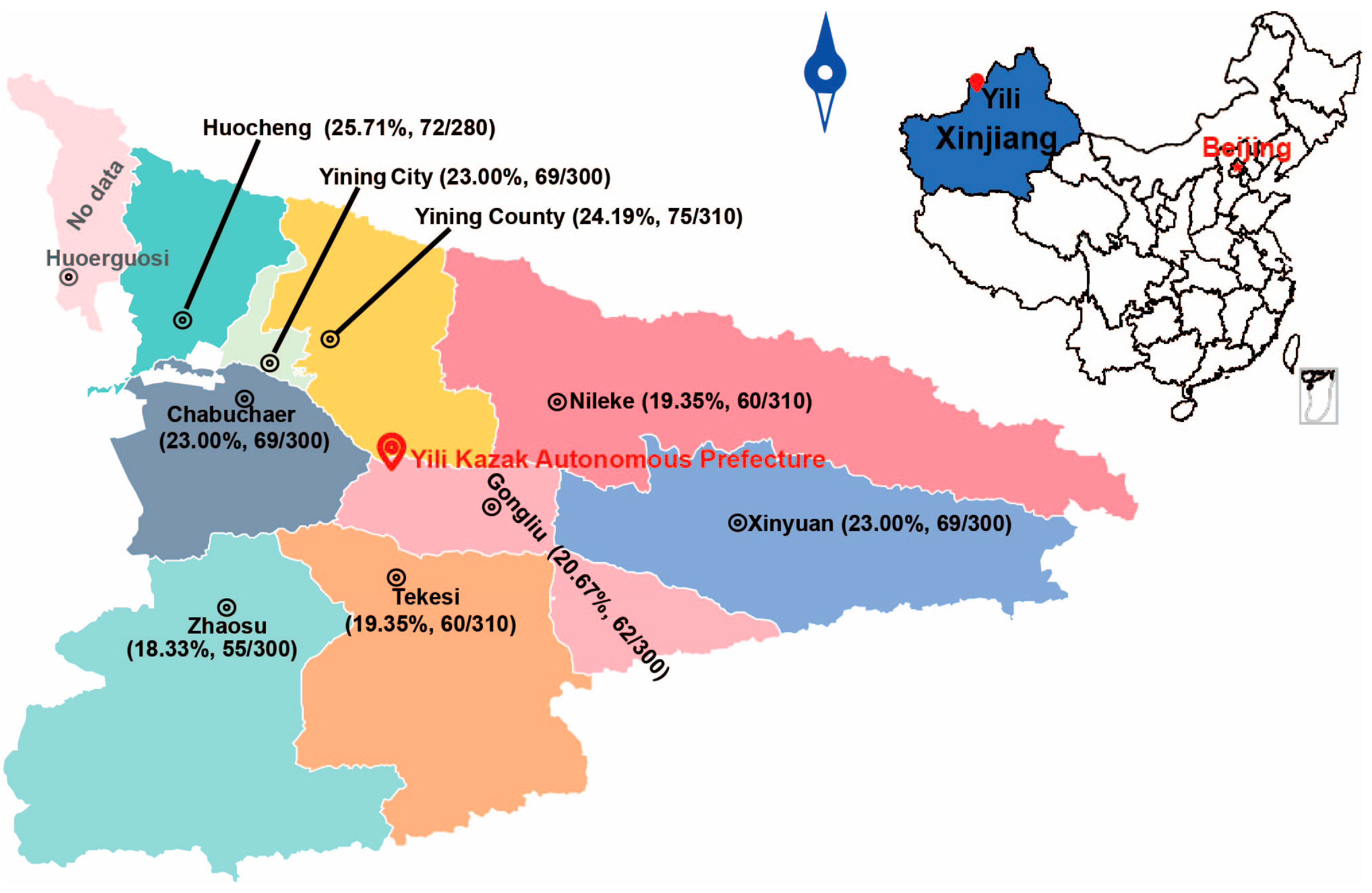

From 2020 to 2024, a total of 2700 sheep livers were visually inspected for cystic lesions during slaughterhouse surveillance across 9 counties in Yili Prefecture of Xinjiang. The surveyed counties included Chabuchaer Xibo Autonomous County (Chabuchaer;

n = 300), Gongliu County (

n = 300), Huocheng County (

n = 280), Nileke County (

n = 310), Tekesi County (

n = 300), Xinyuan County (

n = 300), Yining City (

n = 300), Yining County (

n = 310), and Zhaosu County (

n = 300) (

Figure 1).

2.3. Morphological Characterization

Ninety severely infected cystic liver samples (including calcified cysts) were first washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and their surfaces were carefully wiped with 75% alcohol. Hydatid fluid was aseptically aspirated from the cysts using a 10 mL sterile syringe and then transferred to a 50 mL centrifuge tube for natural sedimentation. The protoscolices (PSCs) were pelleted via centrifugation at 500× g for 5 min, washed three times with PBS, and finally resuspended in 30 mL of PBS. For viability assessment, a 100 μL aliquot of the PSC suspension was stained with 1% methylene blue for 1 min and examined under a light microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). For molecular analysis, 1 mL aliquots of the PSC suspension were stored at −20 °C until DNA extraction.

2.4. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

The frozen PSC suspensions were thawed and homogenized using an orbital shaker (Jingxin Biotech, Shanghai, China). The samples were then centrifuged at 5000× g for 10 min, and the supernatant was carefully discarded. Genomic DNA was extracted using the TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit (TianGen Biotech, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA was eluted in 100 μL of preheated (55 °C) elution buffer and stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

The NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (

nad2) gene (~1500 bp) of

E. granulosus was amplified using primers previously described by Guo et al. [

20]: forward 5′-ATTTTGCGGTCGTCTCTGAT-3′ and reverse 5′-TCCACGAGACCAAGGATACC-3′. PCR was performed in a 25 μL reaction mixture containing 12.5 μL of 2× PCR buffer mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 8.5 μL of nuclease-free water, 1 μL of each primer (10 μM), and 2 μL of template DNA. Amplification was carried out in a thermal cycler (Bio-Rad T100™, Hercules, CA, USA) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 56 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 2 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Each PCR run included both positive (genomic DNA from a confirmed

E. granulosus sample) and negative (nuclease-free water instead of template DNA) controls.

2.5. Phylogenetic Analyses

PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.0% agarose gels. Amplicons that yielded a band of the expected size were purified and sent for Sanger sequencing (Sunny Biotech, Shanghai, China). The obtained

nad2 sequences were compared to known sequences in the GenBank database using the BLAST algorithm (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) (accessed on 28 May 2025). Multiple sequence alignment was performed using Clustal W with default parameters, and the alignments were manually refined using MEGA X (version 10.2.6). A phylogenetic tree was reconstructed based on the aligned sequences using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method. All phylogenetic analyses employed the Kimura 2-parameter model, and the robustness of the inferred topology was assessed with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

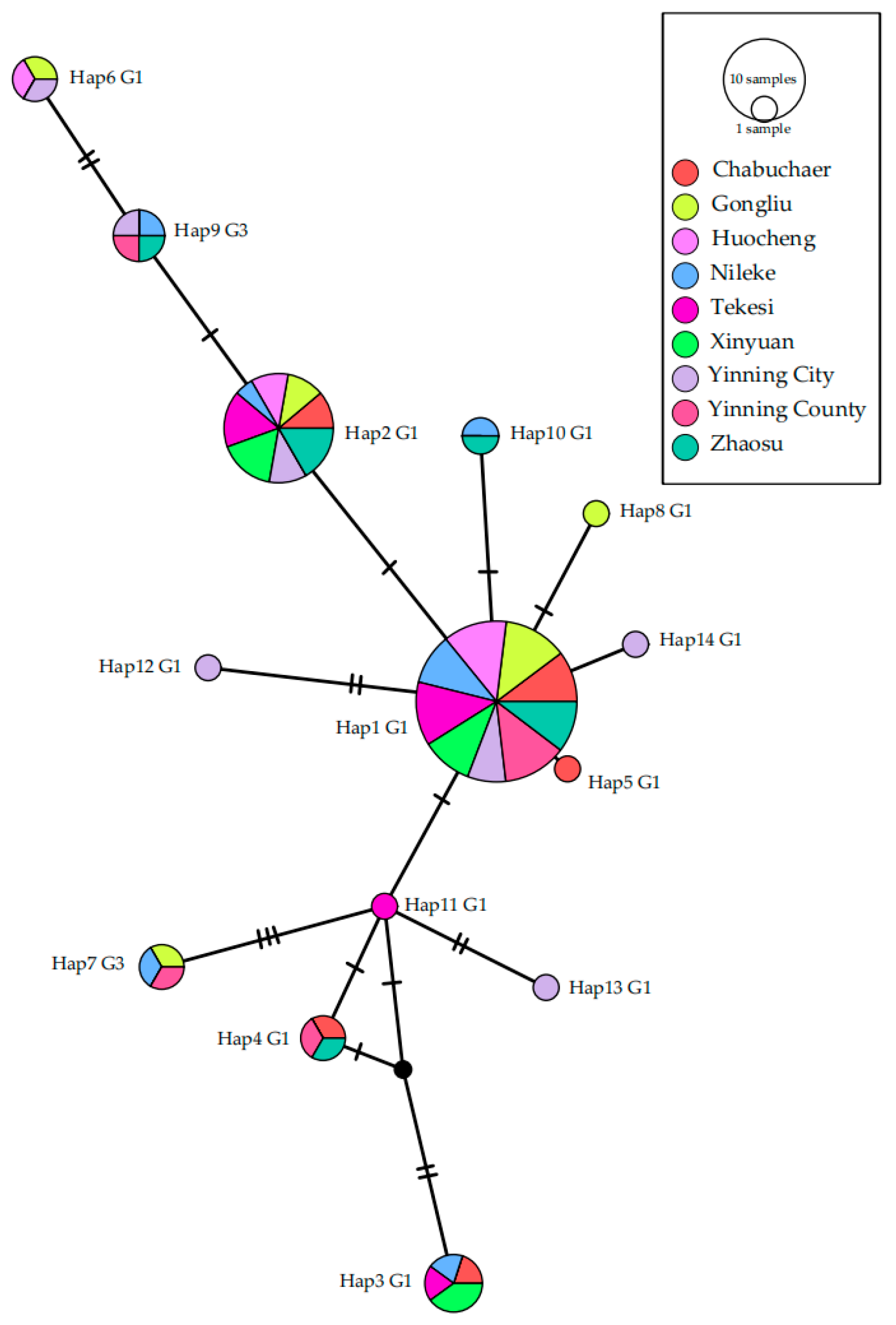

A median-joining haplotype network was constructed using PopArt software (version 1.7) to visualize the relationships among mitochondrial DNA haplotypes (Haps). Genetic diversity indices, including the number of Haps, haplotype diversity (Hd), and nucleotide diversity (π), were calculated using DnaSP software (v6). Neutrality tests, including Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs, were performed to detect deviations from population equilibrium. Population genetic structure was evaluated by calculating pairwise fixation indices (Fst) in Arlequin software (version 3.5.2.2). All unique nad2 sequences generated in this study were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers PX430486 to PX430498.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The prevalence of E. granulosus infection in sheep livers, expressed as a percentage with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), was calculated for each of the nine study counties. Differences in prevalence across counties and years were assessed using Pearson’s chi-square test (χ2), while year and county as risk factors were assessed by multivariable logistic regression. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The statistical analyses for Tajima’s D, Fu’s Fs, and Fst values across different counties were performed automatically by the respective software modules. Specifically, Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs were evaluated using repeated data simulations, while the Fst values were assessed via a permutation test. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

4. Discussion

The Yili River Valley is a pivotal sheep breeding base in Xinjiang and a nationally significant livestock hub, possessing exceptional natural conditions for pastoralism. Despite this, the region has consistently documented persistently high rates of echinococcosis. This endemicity is likely driven by a confluence of factors, including a harsh climate, extensive pastoral systems, suboptimal veterinary public health infrastructure, and frequent cross-border livestock movements. Previous localized studies have reported

E. granulosus infection rates in sheep that exceed the national average by two to six-fold [

16,

21]. Nonetheless, comprehensive, longitudinal surveillance data at a prefecture-wide scale have been lacking. This knowledge gap has obscured the dynamic epidemiological trends of CE and hindered an accurate assessment of transnational transmission risks, underscoring the critical need for the present study.

Our findings address a significant gap in the epidemiological surveillance of

E. granulosus in sheep. While many previous studies have focused primarily on genotyping and genetic polymorphism using PCR-confirmed samples, our approach integrated large-scale, longitudinal monitoring with macroscopic examination. Through a five-year surveillance program across nine counties in Yili Prefecture, we documented a consistently high overall prevalence of 22.0% (95% CI: 20.5–23.6). This prevalence is markedly higher than infection rates previously reported in northern Xinjiang. For instance, it substantially exceeds the 3.9% (14/361) reported in Yili Prefecture and 4.5% (131/2898) in the Altai Region by Guo et al. [

14,

15], as well as the 2.3% (390/17,215) documented in Emin County of Tacheng Region by Yang et al. [

22]. The higher prevalence observed in our study is likely attributable to the inclusion of early and mild infections that were detected macroscopically but are often missed by PCR. This is supported by our practical experience: when we attempted molecular genotyping on a subset of our macroscopically positive samples, PCR amplification was consistently unsuccessful in samples with minimal pathological changes, suggesting a low parasitic DNA load below the assay’s detection limit.

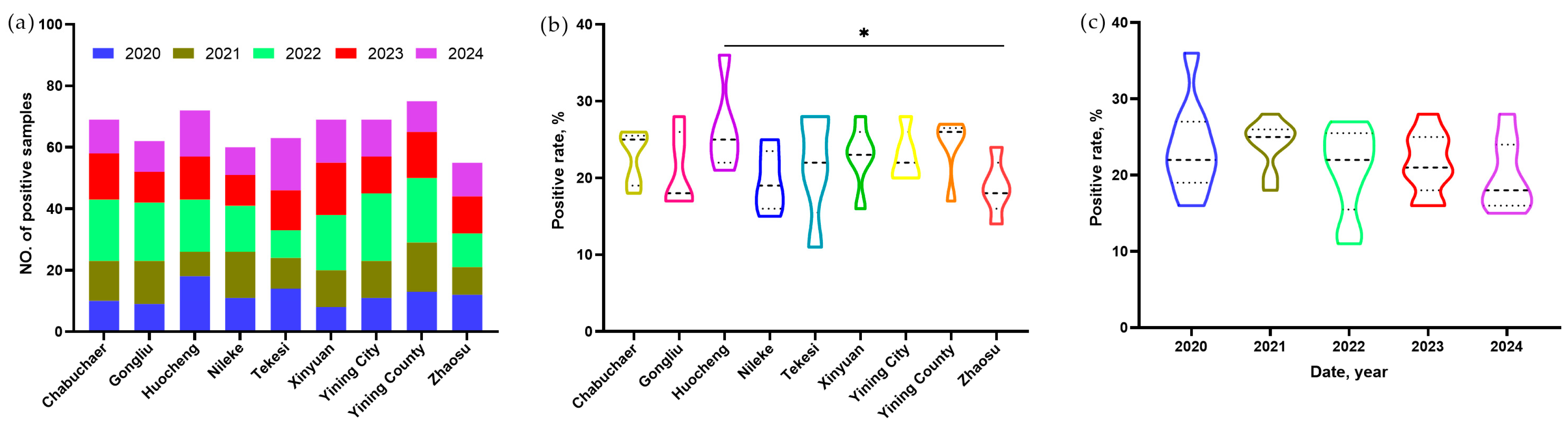

Previous studies have indicated that the infection rate of

E. granulosus in sheep is generally higher in pastoral areas than in agricultural regions of Xinjiang [

23]. However, our investigation in the Yili Prefecture revealed no significant difference in sheep infection rates across its various counties (the total infection rates fluctuating from 18.3% to 25.7%). This homogeneity may be attributed to the prefecture’s distinctive topography and mixed farming–pastoral landscape. Located in northwestern Xinjiang and bordering Kazakhstan, Yili Prefecture is surrounded by mountains on three sides, with the Yili River Valley serving as its core geographical unit [

24]. Agricultural and pastoral areas are interwoven and indistinctly demarcated throughout the prefecture, often exhibiting a mixed “agro-pastoral” pattern, which may explain the relatively uniform spatial distribution of

E. granulosus infections. On the other hand, significant year-to-year variations were observed in some areas, with prevalence rates ranging from, for example, 11.3% in Tekesi County (2022) to 36.0% in Huocheng County (2020). A potential explanation for this disparity lies in the heterogeneous origins of the sheep, given that control strategies likely vary from one pasture to another. On the contrary, five years of surveillance data from 2020 to 2024 revealed no significant differences in annual prevalence rates (

p > 0.05). This may be attributed to the relative stability of the annual CE control strategies in the Yili region, as the prevention and control measures were strictly implemented in accordance with the annual guidelines issued by the Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of Xinjiang, primarily consisting of dog deworming and lamb vaccination. However, this study primarily focused on adult sheep (mostly aged 1–4 years) from slaughterhouses, in which the protective immunity from earlier vaccination may have waned or diminished. Furthermore, the vast grasslands in the Yili region are frequented by wildlife such as foxes and wolves, which serve as significant reservoirs of infection. Relying solely on deworming domestic dogs may therefore be insufficient to disrupt the transmission cycle at its source. The persistently high prevalence can seriously affect sheep health, leading to issues such as sheep death, slow growth, prolonged time to slaughter, organ discards and increased rearing costs [

25]. Given that multiple factors, such as livestock farming scale and annual climatic variations, can influence the transmission of CE, it is necessary to develop control strategies through multi-sectoral collaboration [

26,

27].

Furthermore, a notably higher infection rate was observed in Yining City (23.0%), and the highest genetic diversity (Hd = 0.911, π = 0.00277) was also found in this city, likely associated with its unique geographical and socioeconomic role. As the capital and most populous city of Yili Prefecture, Yining City has the highest daily sheep slaughter volume in the region. Although it is not a major agricultural or pastoral production area itself, most of the sheep slaughtered in the city are sourced from various counties across Yili Prefecture. This influx of animals from multiple origins may contribute to the higher observed infection rate and genetic diversity in Yining City.

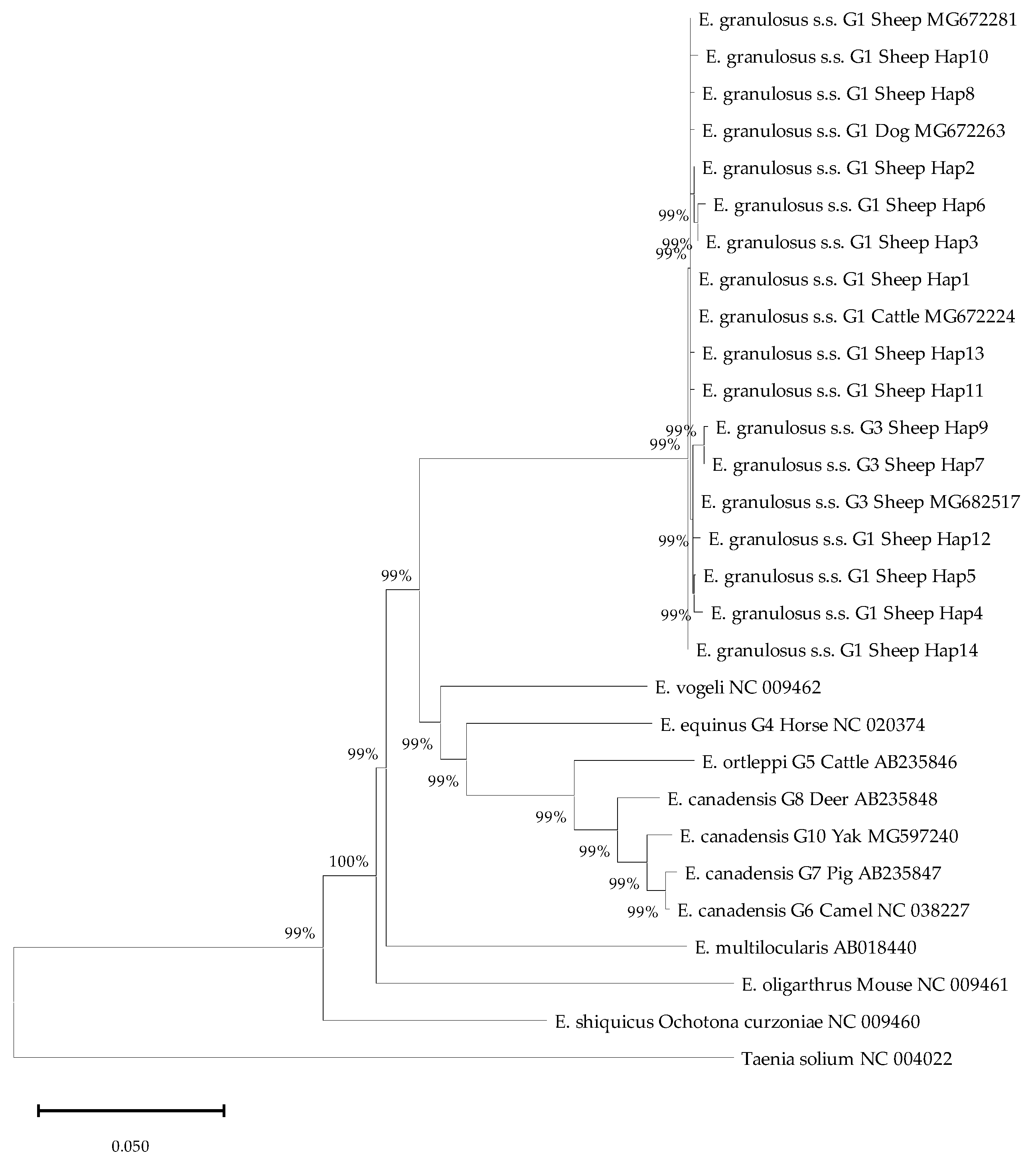

Molecular genotyping of hydatid cysts, targeting the

nad2 gene, confirmed the exclusive circulation of the

E. granulosus s. s. G1 genotype in our samples. This finding is consistent with the global predominance of this livestock-adapted strain. The dominance of G1 aligns with recent reports from the East Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang [

28] and is well-documented across other endemic provinces in China, including the Altai region of northern Xinjiang [

15], Xizang Autonomous Region [

18,

29,

30,

31], Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region [

32], and Sichuan Province [

19]. Globally, the G1 genotype is notorious for its pronounced zoonotic potential, constituting a major public health threat from the Mediterranean Basin [

33] to Pakistan [

34], Kenya [

35], and North Africa [

36]. The shared global genotype profile suggests the possibility of cross-border transmission pathways. However, validating the direction and intensity of such transmission requires future high-resolution population genetic studies (e.g., using microsatellite or SNP-based haplotyping). Furthermore, as this study primarily analyzed samples with more severe lesions (including calcified cysts), the findings may be subject to selection bias. Future studies should therefore include and successfully analyze samples with mild lesions to comprehensively validate the present results.

The dominance of the G1 genotype in sheep reservoirs directly amplifies the human health risk within a One Health framework. This is critically relevant to Yili, as human CE cases in Xinjiang are mainly caused by the G1 genotype [

23,

37], and the prevalence of

Echinococcus in dogs can reach 5.8% (5557/200,165) in Xinjiang [

38]. These factors sustain a pernicious transmission cycle involving dogs (definitive hosts), the environment (eggs), and both sheep and humans (intermediate hosts) [

39]. This cycle is profoundly amplified by traditional slaughter practices, where infected offal is routinely fed to dogs. This dangerous feedback loop mirrors transmission dynamics observed in other endemic regions such as Kenya and Pakistan [

35,

40,

41], highlighting a universal challenge in CE control [

42]. However, this study did not examine environmental or canine fecal samples. Therefore, it remains unclear whether the persistently high prevalence of ovine CE in Yili is associated with dogs. Future studies are needed to investigate

E. granulosus infections in dogs in Yili.

Our study identified 14 Haps of

E. granulosus s.s. circulating in sheep across Yili Prefecture. This level of haplotype diversity is broadly consistent with several previous reports from Xinjiang and other endemic regions in China. For instance, studies targeting the

cox1 gene identified 12 Haps in Hejing County [

16] and 16 Haps in the Altai region [

15], while 13 Haps were reported in sheep from Xizang [

43]. In contrast, other studies have reported lower haplotype diversity within Xinjiang. Guo et al. [

14] found only seven Haps across a wide geographical area encompassing Urumqi, Yili, Tacheng, and Altai. Similarly, Yan et al. [

44] documented 10 Haps in Yili Prefecture and 9 Haps in Changji Hui Autonomous Prefecture of Xinjiang. The discrepancies in reported haplotype diversity across studies are likely multifactorial. Key influencing variables include the sample size (with larger, more comprehensive surveys like ours capturing greater diversity), the geographical scale and sampling strategy (targeting a single prefecture vs. multiple pooled regions), the choice of genetic marker (

nad2 in our study vs. cox1 in others), and potential temporal fluctuations in parasite population structure.

The F

st values, which were all negligible and not significantly different from zero (range: −0.09964 to 0.01099;

p > 0.05), indicate a pronounced lack of genetic differentiation among

E. granulosus populations across the nine counties of Yili Prefecture. Notably, the lowest F

st value was observed between Nileke and Yining County (F

st = −0.09964), suggesting particularly frequent genetic exchange between these two populations. Actually, the two counties are adjacent (

Figure 1), which is likely the reason for the minimal genetic variation in

E. granulosus between them. Similarly, pairwise comparisons involving the central hub of Yining City (e.g., with Xinyuan and Yining County) and other counties (e.g., Xinyuan with Zhaosu) yielded values asymptotically approaching zero, further reinforcing the genetic homogeneity of the parasite population throughout the region. This panmixia is most parsimoniously explained by the extensive movement of infected intermediate hosts (sheep) through regional livestock trade and pastoral migration patterns.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the reliance on animals presented for slaughter means the sample may not be fully representative of the general sheep population in the region, as factors such as age, health, and management practices of slaughtered animals could introduce a potential selection bias. Second, the absence of age and sex-stratified data prevented the analysis of associated risk factors, which is crucial for understanding transmission dynamics. For future research, serological surveys in farms, combined with environmental sampling and the testing of feces from definitive host dogs, are recommended to enable a comprehensive assessment of CE in Yili, Xinjiang.