Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals Novel and Differential Long-Noncoding RNA Responses Underlying Interferon-Mediated Antiviral Regulation in Porcine Alveolar Macrophages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Ethics Statement and Animal Cell Sources

2.2. Virus Infection and IFN Treatment

2.3. RNA Transcriptomic Library Construction

2.4. RNA Transcriptomic Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

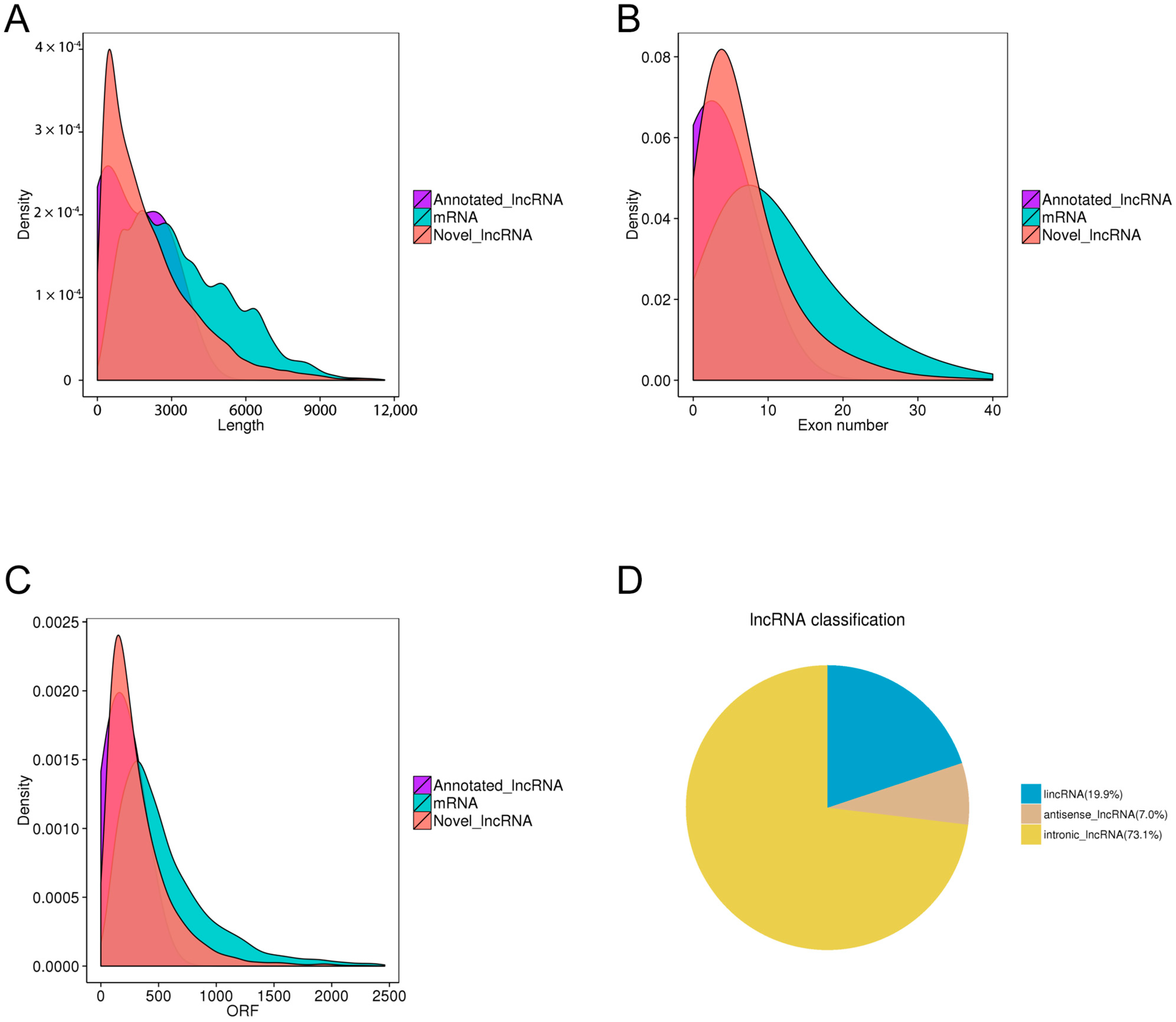

3.1. LncRNA Compositions and Identification Across the PAM Samples

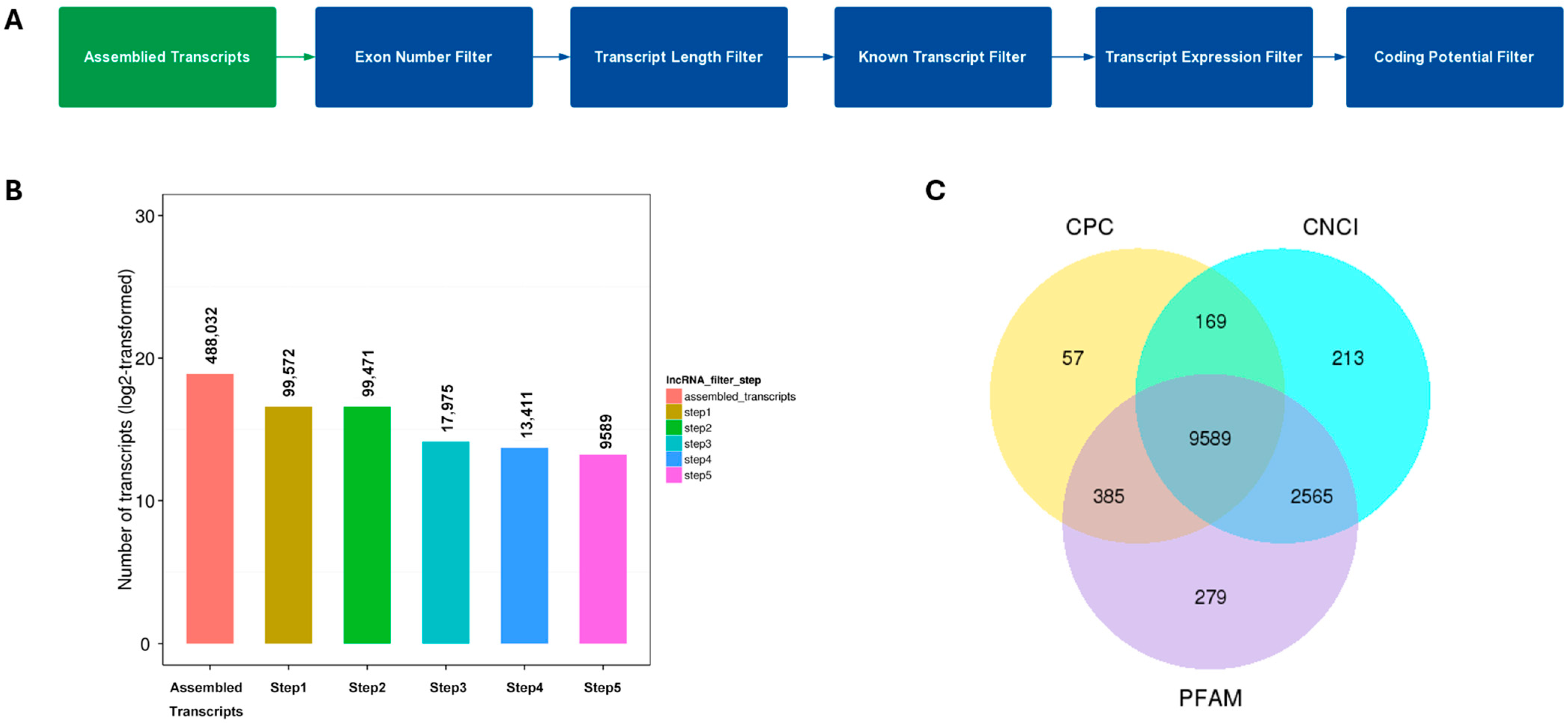

3.2. Filtering of Candidate lncRNAs

3.3. Quantification of lncRNAs, mRNA and TUCP

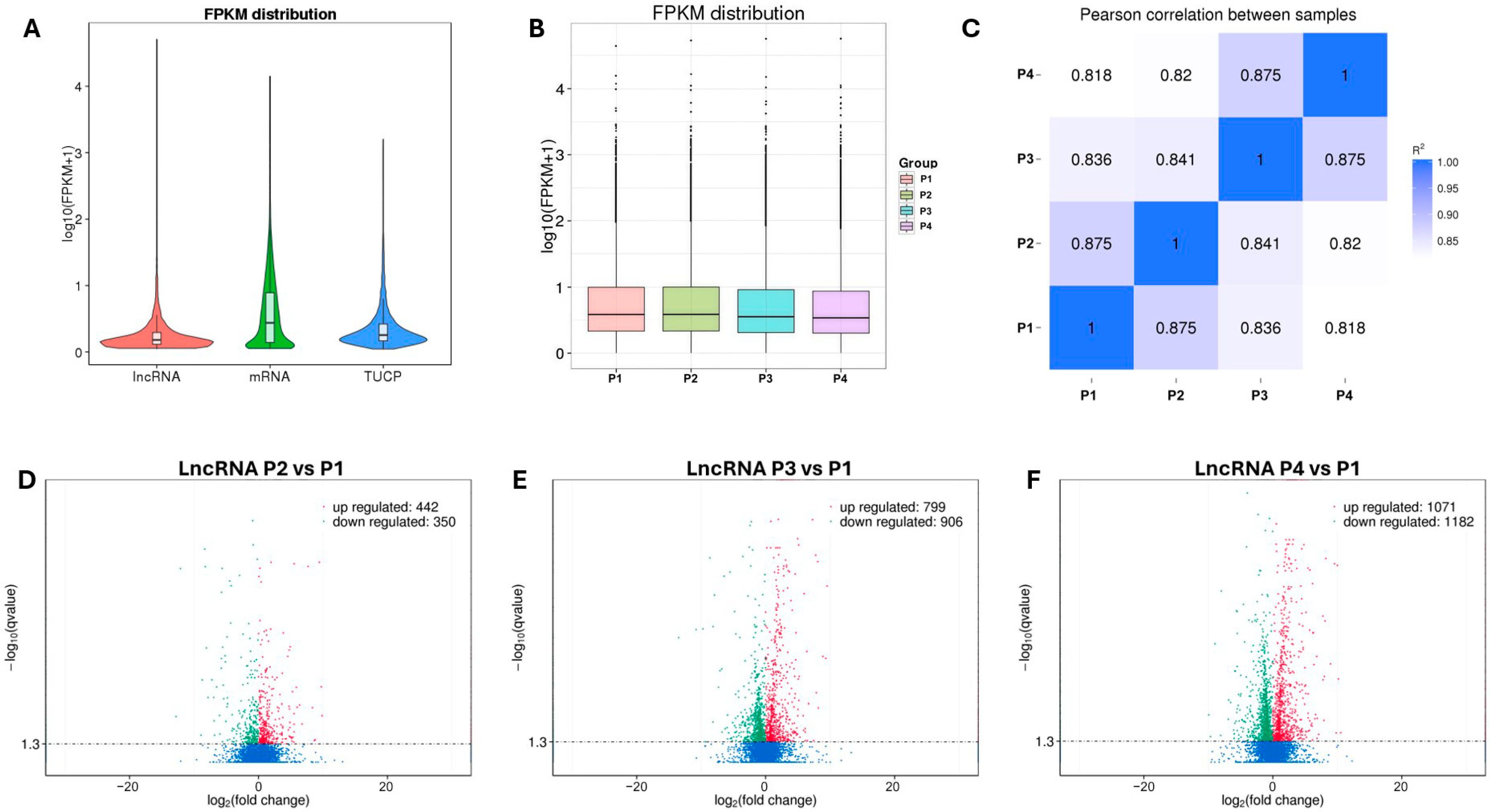

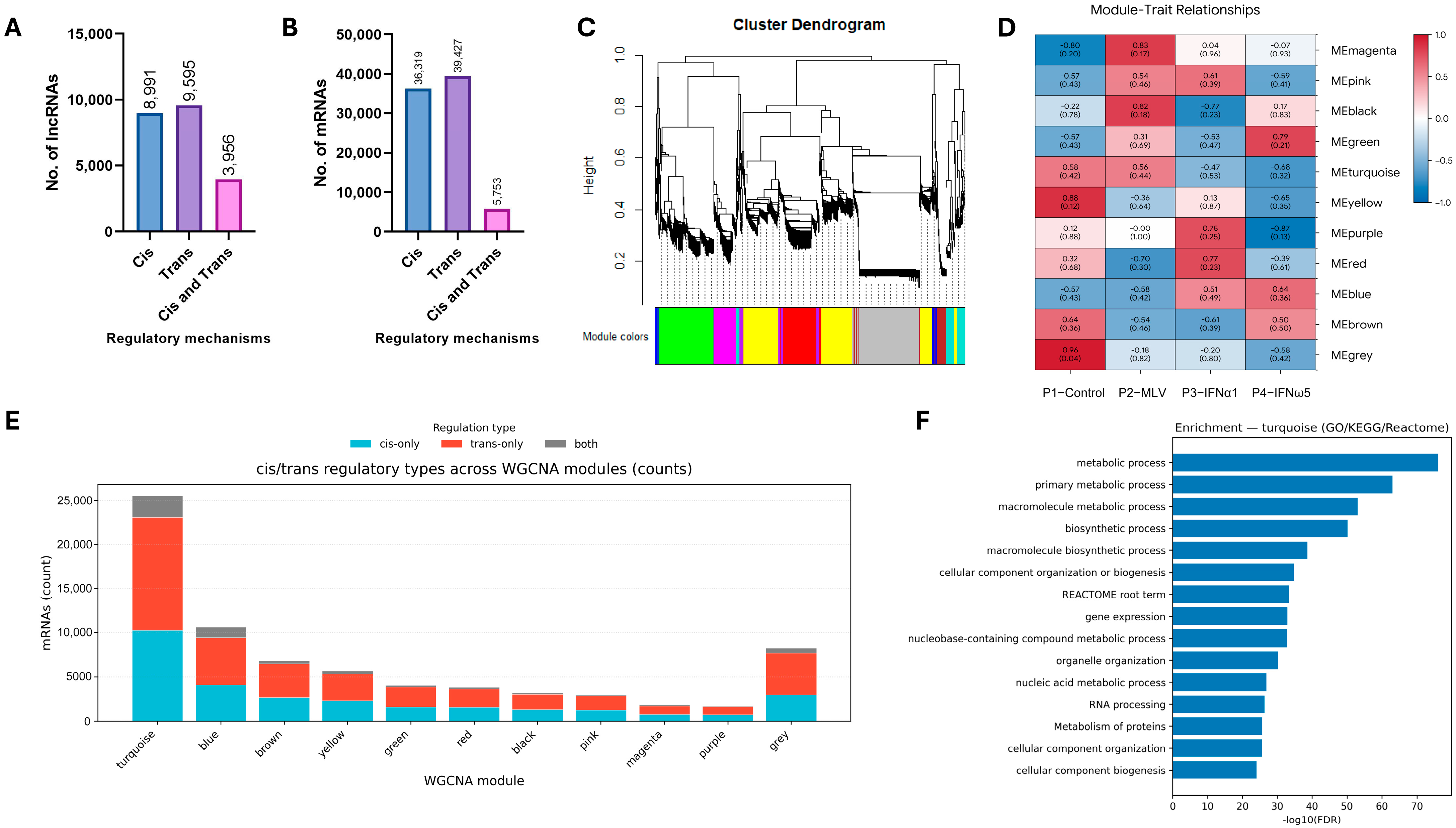

3.4. Identification of Interferon-Associated lncRNA–mRNA Co-Expression Modules and Regulatory Patterns

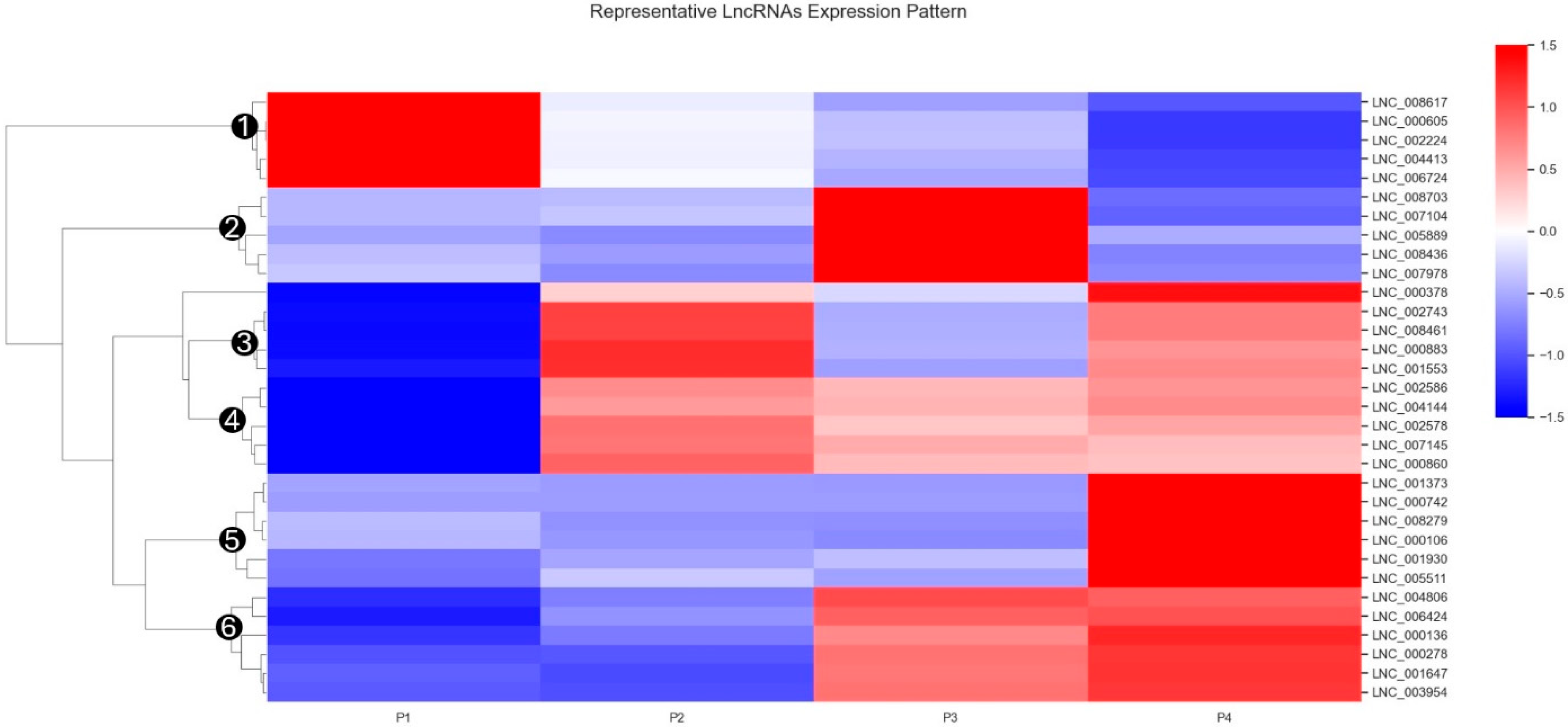

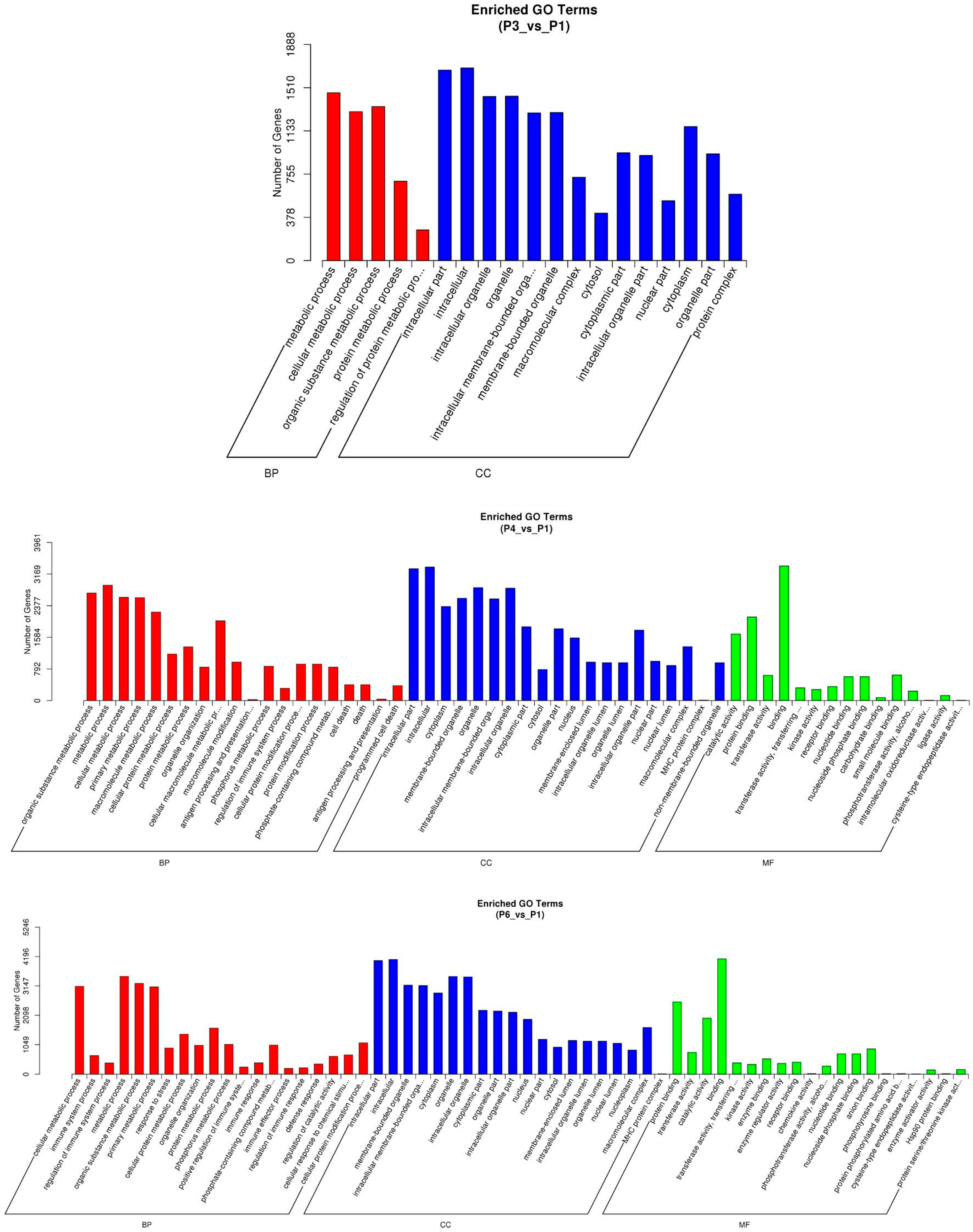

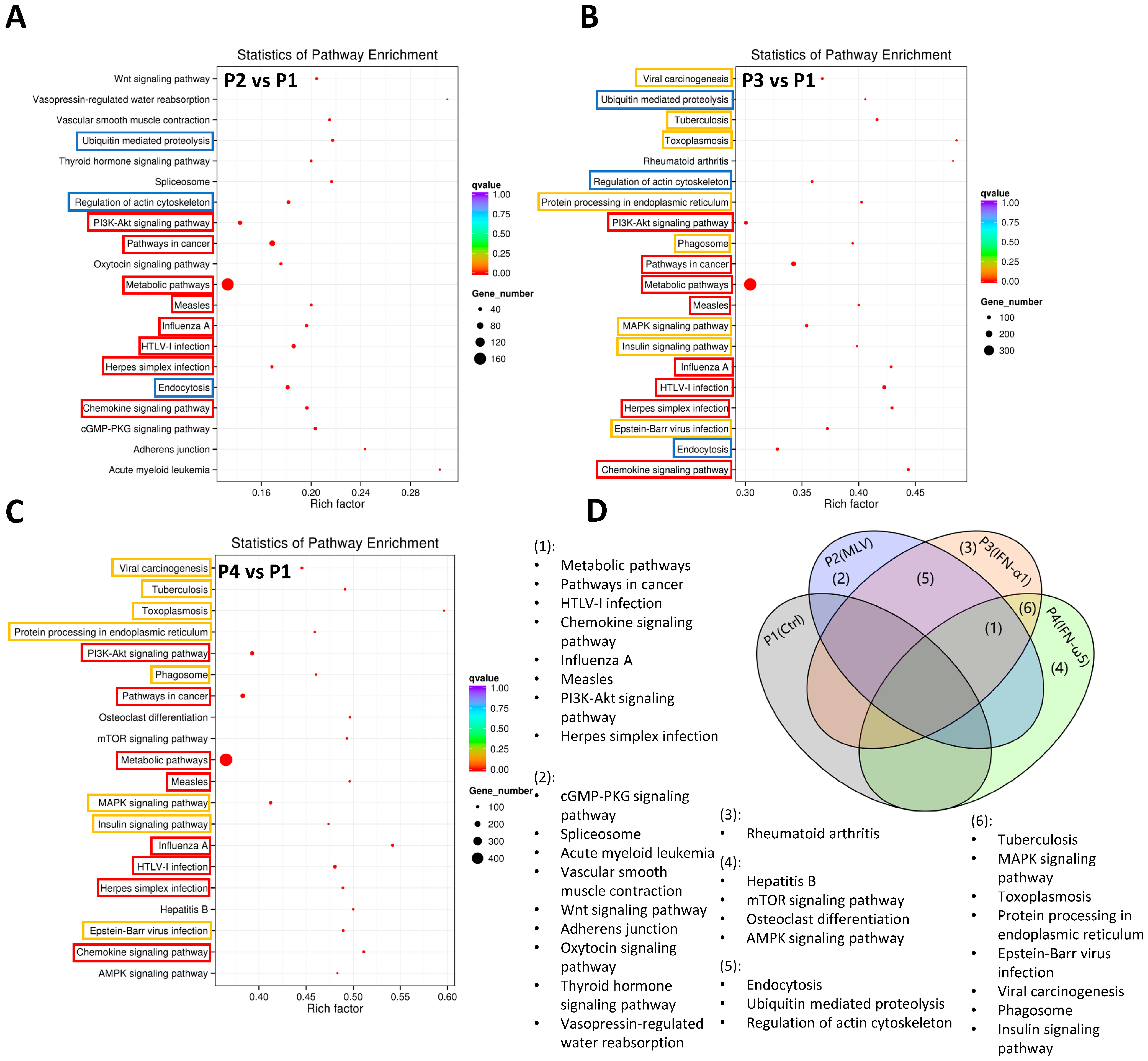

3.5. Gene Ontology and KEGG Analysis of LncRNA-Targeted Genes

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meulenberg, J.J. PRRSV, the virus. Vet. Res. 2000, 31, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbalenya, A.E.; Enjuanes, L.; Ziebuhr, J.; Snijder, E.J. Nidovirales: Evolving the largest RNA virus genome. Virus Res. 2006, 117, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokland, T. The structural biology of PRRSV. Virus Res. 2010, 154, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanin, D.E.; Ge, Y.; Marinkovic, E.; Kabat, A.M.; Castoldi, A.; Caputa, G.; Grzes, K.M.; Curtis, J.D.; Thompson, E.A.; Willenborg, S.; et al. A common framework of monocyte-derived macrophage activation. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eabl7482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Adeyemi, O.; Miller, L.C.; Sang, Y. Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals Novel and Differential Circular RNA Responses Underlying Interferon-Mediated Antiviral Regulation in Porcine Alveolar Macrophages. Viruses 2025, 17, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Gao, N.; Xu, Z.; Guo, C.; He, S.; Zhang, G.; Chen, Y.; et al. Unveiling Shared Immune Responses in Porcine Alveolar Macrophages during ASFV and PRRSV Infection Using Single-Cell RNA-seq. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netea, M.G.; Joosten, L.A.; Latz, E.; Mills, K.H.; Natoli, G.; Stunnenberg, H.G.; O’Neill, L.A.; Xavier, R.J. Trained immunity: A program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science 2016, 352, aaf1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, J.S.; Amaral, P.P.; Carninci, P.; Carpenter, S.; Chang, H.Y.; Chen, L.L.; Chen, R.; Dean, C.; Dinger, M.E.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs: Definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowel, W.K.; Kotzin, J.J.; McCright, S.J.; Neal, V.D.; Henao-Mejia, J. Control of Immune Cell Homeostasis and Function by lncRNAs. Trends Immunol. 2018, 39, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Concha, M.; Onate, A.A. Long Non-coding RNAs in the Regulation of the Immune Response and Trained Immunity. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Bi, J.; Yang, C.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Deng, J.; Wang, L.; Gao, X.; Lin, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Long non-coding RNA LOC103222771 promotes infection of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in Marc-145 cells by downregulating Claudin-4. Vet. Microbiol. 2023, 286, 109890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez, B.; Prats-Mari, L.; Unfried, J.P.; Fortes, P. LncRNAs in the Type I Interferon Antiviral Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Peng, J.; Song, S.; Xu, G.; Yang, N.; Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; et al. Genome-Wide mRNA and Long Non-Coding RNA Analysis of Porcine Trophoblast Cells Infected with Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Associated with Reproductive Failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Ge, L.; Dong, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhou, C.; Ma, C.; Wang, Y.; Su, F.; Jiang, Y. Global miRNA, lncRNA, and mRNA Transcriptome Profiling of Endometrial Epithelial Cells Reveals Genes Related to Porcine Reproductive Failure Caused by Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, K.; Xia, Y.; Wu, Q.; Yin, M.; Zhao, H.; Chen, X.W. Analysis of whole transcriptome reveals the immune response to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection and tylvalosin tartrate treatment in the porcine alveolar macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1506371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, N.; Wang, C.; Liu, S.; Miao, Q.; Zhou, L.; Ge, X.; Han, J.; Guo, X.; Yang, H. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Dynamic Gene Expression Profiles in Porcine Alveolar Macrophages in Response to the Chinese Highly Pathogenic Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1538127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yu, H.; Qi, A.; Zhang, T.; Huo, Y.; Tu, Q.; Qi, C.; Wu, H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; et al. Regulatory Non-Coding RNAs during Porcine Viral Infections: Potential Targets for Antiviral Therapy. Viruses 2024, 16, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sang, E.R.; Adeyemi, O.; Miller, L.C.; Sang, Y. Comparative transcriptomics reveals small RNA composition and differential microRNA responses underlying interferon-mediated antiviral regulation in porcine alveolar macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1016268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Luo, H.; Bu, D.; Zhao, G.; Yu, K.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhao, Y. Utilizing sequence intrinsic composition to classify protein-coding and long non-coding transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, Z.Q.; Liu, X.Q.; Zhao, S.Q.; Wei, L.; Gao, G. CPC: Assess the protein-coding potential of transcripts using sequence features and support vector machine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W345–W349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.D.; Wakefield, M.J.; Smyth, G.K.; Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: Accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, D.S.; Miller, L.C.; Li, J.; Van Geelen, A.; Sang, Y. Transcriptomic Analysis of Liver Indicates Novel Vaccine to Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Virus Promotes Homeostasis in T-Cell and Inflammatory Immune Responses Compared to a Commercial Vaccine in Pigs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 791034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Miller, L.C.; Sang, Y. Current Status of Vaccines for Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome: Interferon Response, Immunological Overview, and Future Prospects. Vaccines 2024, 12, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarroux, J.; Morillon, A.; Pinskaya, M. History, Discovery, and Classification of lncRNAs. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 1008, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, Y.B.; Kleinman, C.L.; Landry-Voyer, A.M.; Majewski, J.; Bachand, F. Polyadenylation-dependent control of long noncoding RNA expression by the poly(A)-binding protein nuclear 1. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1003078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilusz, J.E.; JnBaptiste, C.K.; Lu, L.Y.; Kuhn, C.D.; Joshua-Tor, L.; Sharp, P.A. A triple helix stabilizes the 3’ ends of long noncoding RNAs that lack poly(A) tails. Genes. Dev. 2012, 26, 2392–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, P.; Luo, S.; Lu, J.Y.; Shen, X. Cis- and trans-acting lncRNAs in pluripotency and reprogramming. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2017, 46, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Chen, J.; Yin, X.; Zhou, J. Current understanding on long non-coding RNAs in immune response to COVID-19. Virus Res. 2023, 323, 198956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Lin, F.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, M.; Luo, M. Long noncoding RNAs as emerging regulators of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 700184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Qi, X.; Xie, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, S.; Sun, M.A.; Bao, W. LncRNA446 Regulates Tight Junctions by Inhibiting the Ubiquitinated Degradation of Alix after Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Infection. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0188422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Tao, J.; Li, B.; Shi, Y.; Liu, H. The lncRNA HCG4 regulates the RIG-I-mediated IFN production to suppress H1N1 swine influenza virus replication. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1324218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, B.; Kim, S.C.; Kim, W.I.; Kim, J.M. Integrative time-serial networks for genome-wide lncRNA-mRNA interactions reveal interferon-inducible antiviral and T-cell receptor regulations against PRRSV infection. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2023, 147, 104759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ma, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, R.; Luo, C.; Zeshan, B.; Yang, Z.; Qiu, L.; Wang, J.; et al. The transcriptional characteristics of NADC34-like PRRSV in porcine alveolar macrophages. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1022481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Pan, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Tian, Z.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y. Unveiling the long non-coding RNA profile of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus-infected porcine alveolar macrophages. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, O.; Xia, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zeng, S.; Zou, C.; Hu, F.; Xu, Q.; Huang, Y.; Geng, R.; Hu, G.; et al. Integrative transcriptomic profiling of mRNA, miRNA, circRNA, and lncRNA in alveolar macrophages isolated from PRRSV-infected porcine. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1258778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, L.C.; Anderson, S.J.; Buckley, A.C.; Schirtzinger, E.E.; Hasan, M.; Sarlo Davila, K.M.; Fleming, D.S.; Lager, K.M.; Li, J.; Sang, Y. Replication-competent recombinant porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus expressing antiviral cytokine interferon-omega5 as a modified live virus vaccine. Vet. Microbiol. 2025, 301, 110366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.C.; Anderson, S.J.; Buckley, A.C.; Schirtzinger, E.E.; Hasan, M.; Sarlo Davila, K.M.; Fleming, D.S.; Lager, K.M.; Li, J.; Sang, Y. Vaccine Efficacy of a Replication-Competent Interferon-Expressing Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) Virus Against NADC-34 Challenge. Vaccines 2025, 13, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.X.; Jin, X.; Chen, J.; Peng, L.; Wang, D.L.; Li, Y.; Yao, X.Y.; Liao, J.Y.; He, J.H.; et al. Overexpression of lncRNAs with endogenous lengths and functions using a lncRNA delivery system based on transposon. J. Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, E.; Erman, B. Long noncoding RNA (lincRNA), a new paradigm in gene expression control. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2017, 17, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample Name | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total reads | 88,711,244 | 81,698,196 | 83,905,840 | 90,253,536 |

| Total mapped | 77,138,322 (86.95%) | 70,481,620 (86.27%) | 74,412,691 (88.69%) | 80,391,522 (89.07%) |

| Multiple mapped | 3,705,473 (4.18%) | 3,832,386 (4.69%) | 3,838,200 (4.57%) | 4,078,578 (4.52%) |

| Uniquely mapped | 73,432,849 (82.78%) | 66,649,234 (81.58%) | 70,574,491 (84.11%) | 76,312,944 (84.55%) |

| Read-1 | 36,746,731 (41.42%) | 33,426,675 (40.91%) | 35,279,472 (42.05%) | 38,240,953 (42.37%) |

| Read-2 | 36,686,118 (41.35%) | 33,222,559 (40.66%) | 35,295,019 (42.07%) | 38,071,991 (42.18%) |

| Reads map to ‘+’ | 36,693,528 (41.36%) | 33,290,907 (40.75%) | 35,265,462 (42.03%) | 38,129,368 (42.25%) |

| Reads map to ‘−’ | 36,739,321 (41.41%) | 33,358,327 (40.83%) | 35,309,029 (42.08%) | 38,183,576 (42.31%) |

| Non-splice reads | 46,432,078 (52.34%) | 42,026,077 (51.44%) | 44,658,740 (53.22%) | 48,409,573 (53.64%) |

| Splice reads | 27,000,771 (30.44%) | 24,623,157 (30.14%) | 25,915,751 (30.89%) | 27,903,371 (30.92%) |

| Reads mapped in proper pairs | 70,997,620 (80.03%) | 64,459,008 (78.9%) | 68,346,900 (81.46%) | 73,800,280 (81.77%) |

| Proper-paired reads map to different chromosome | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Adeyemi, O.; Miller, L.C.; Sang, Y. Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals Novel and Differential Long-Noncoding RNA Responses Underlying Interferon-Mediated Antiviral Regulation in Porcine Alveolar Macrophages. Pathogens 2026, 15, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010035

Li J, Adeyemi O, Miller LC, Sang Y. Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals Novel and Differential Long-Noncoding RNA Responses Underlying Interferon-Mediated Antiviral Regulation in Porcine Alveolar Macrophages. Pathogens. 2026; 15(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jiuyi, Oluwaseun Adeyemi, Laura C. Miller, and Yongming Sang. 2026. "Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals Novel and Differential Long-Noncoding RNA Responses Underlying Interferon-Mediated Antiviral Regulation in Porcine Alveolar Macrophages" Pathogens 15, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010035

APA StyleLi, J., Adeyemi, O., Miller, L. C., & Sang, Y. (2026). Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals Novel and Differential Long-Noncoding RNA Responses Underlying Interferon-Mediated Antiviral Regulation in Porcine Alveolar Macrophages. Pathogens, 15(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010035