Prevalence of Rickettsia spp. Infection in Ticks Collected from Shelter Dogs in Tulcea County, Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tick Collection, Morphological Identification and Pooling Procedure

2.2. DNA Extraction

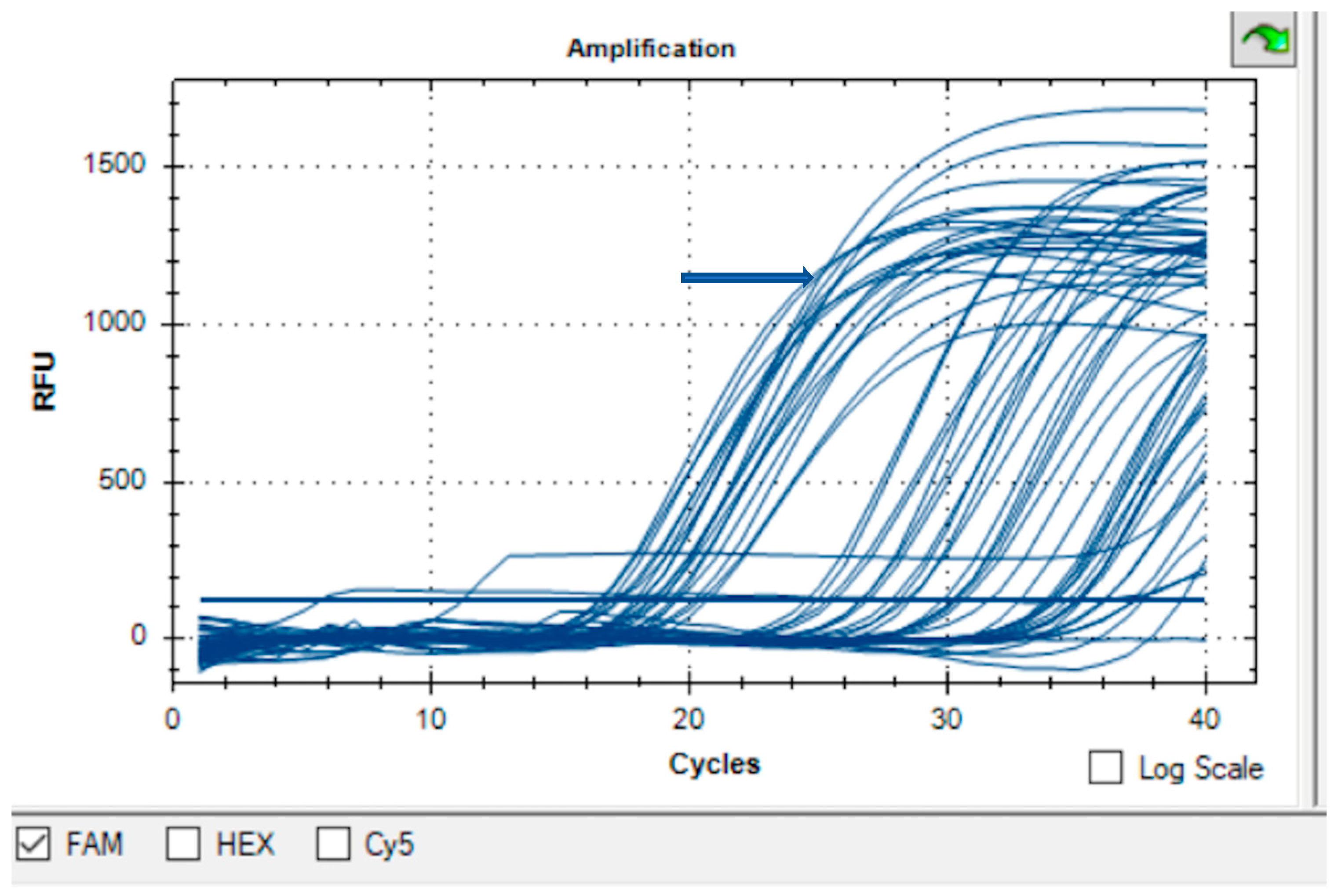

2.3. Molecular Detection: Real-Time Polymerase Chain-Reaction (qPCR)

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

- Rhipicephalus sanguineus s.l.: 88/94 pools (93.6%)

- Ixodes ricinus: 15/17 pools (88.2%)

- Dermacentor marginatus: 7/8 pools (87.5%)

- Dermacentor reticulatus: 13/13 pools (100%)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| MIR | Minimum Infection Rate |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PPR | Pool Positivity Rate |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| SFG | Spotted Fever Group |

| TBDs | Tick-borne Diseases |

References

- Martinescu, G.; Roman, C.; Acatrinei, D.; Ivãnescu, L.; Iacob, O.; Miron, L.D.; Maurelli, M.P.; Ciucã, L. Detection of the co-infections with Borrelia, Anaplasma, and Ehrlichia species in dogs with babesiosis in North-Eastern Romania. Rev. Rom. Med. Vet. 2022, 32, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ionita, M.; Silaghi, C.; Mitrea, I.L.; Edouard, S.; Parola, P.; Pfister, K. Molecular detection of Rickettsia conorii and other zoonotic spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks, Romania. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2016, 7, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Fuente, J.; Estrada-Pena, A.; Venzal, J.M.; Kocan, K.M.; Sonenshine, D.E. Overview: Ticks as vectors of pathogens that cause disease in humans and animals. Front. Biosci. 2008, 13, 6938–6946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, T.; Matei, I.A.; Novac, C.Ș.; Kalmár, Z.; Borșan, S.-D.; Panait, L.-C.; Gherman, C.M.; Ionică, A.M.; Papuc, I.; Mihalca, A.D. Spotted fever group Rickettsia spp. diversity in ticks and the first report of Rickettsia hoogstraalii in Romania. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Dortz, L.L.; Rouxel, C.; Polack, B.; Boulouis, H.-J.; Lagrée, A.-C.; Deshuillers, P.L.; Haddad, N. Tick-borne diseases in Europe: Current prevention, control tools and the promise of aptamers. Vet. Parasitol. 2024, 328, 110190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivănescu, L.; Miron, L.D.; Martinescu, G. Influența Schimbărilor Climatice Asupra Vectorilor și Bolilor Vectoriale; Editura Ion Ionescu de la Brad: Iași, Romania, 2023; ISBN 978-973-147-480-9. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, M.O.; Tolf, C.; Tamba, P.; Stefanache, M.; Waldenström, J.; Dobler, G.; Chițimia-Dobler, L. Canine tick-borne diseases in pet dogs from Romania. Parasites Vectors 2017, 10, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coipan, E.; Vladimirescu, A.; Ciolpan, O.; Teodorescu, I. Tick species (Acari: Ixodoidea) distribution, seasonality and host associations in Romania. Trav. Mus. Natl. Hist. Nat. “Grigore Antipa” 2011, 54, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raileanu, C.; Moutailler, S.; Porea, D.; Oslobanu, L.; Anita, D.; Anita, A.; Vayssier-Taussat, M.; Savuta, G. Molecular evidence of Rickettsia spp., Anaplasma phagocytophilum and “Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis” in ticks from natural and urban habitats in Eastern Romania. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2018, 18, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Peña, A.; Mihalca, A.D.; Petney, T.N. (Eds.) Ticks of Europe and North Africa; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalca, A.D.; Gherman, C.M.; Magdaş, C.; Dumitrache, M.O.; Györke, A.; Sándor, A.D.; Domșa, C.; Oltean, M.; Mircean, V.; Mărcuțan, D.I.; et al. Ixodes ricinus is the dominant questing tick in forest habitats in Romania: Results from a countrywide dragging campaign. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2012, 58, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, I.A.; Kalmár, Z.; Lupşe, M.; D’Amico, G.; Ionică, A.M.; Dumitrache, M.O.; Gherman, C.M.; Mihalca, A.D. Risk of exposure to rickettsial infections and human granulocytic anaplasmosis associated with Ixodes ricinus tick bites in humans in Romania: A multiannual study. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2017, 8, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otranto, D.; Testini, G.; Dantas-Torres, F.; Latrofa, M.S.; Diniz, P.P.V.D.P.; De Caprariis, D.; Lia, R.P.; Mencke, N.; Stanneck, D.; Capelli, G.; et al. Diagnosis of canine vector-borne diseases in young dogs: A longitudinal study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 3316–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, J.J.; Williams, K.; Shukla, M.; Snyder, E.E.; Nordberg, E.K.; Ceraul, S.M.; Dharmanolla, C.; Rainey, D.; Soneja, J.; Shallom, J.M.; et al. Rickettsia phylogenomics: Unwinding the intricacies of obligate intracellular life. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanton, L.S. The rickettsioses. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 33, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoult, D. Introduction to rickettsioses, ehrlichioses, and anaplasmosis. In Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015; pp. 2194–2197. ISBN 978-1-4557-4801-3. [Google Scholar]

- Portillo, A.; Santibáñez, S.; García-Álvarez, L.; Palomar, A.M.; Oteo, J.A. Rickettsioses in Europe. Microbes Infect. 2015, 17, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mărcuțan, I.-D.; Kalmár, Z.; Ionică, A.M.; D’Amico, G.; Mihalca, A.D.; Vasile, C.; Sándor, A.D. Spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks of migratory birds in Romania. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borșan, S.-D.; Ionică, A.M.; Galon, C.; Toma-Naic, A.; Peștean, C.; Sándor, A.D.; Moutailler, S.; Mihalca, A.D. High diversity, prevalence, and co-infection rates of tick-borne pathogens in ticks and wildlife hosts in an urban area in Romania. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 645002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, A.-T.; Yun, B.-R.; Yoo, M.-S.; Lim, J.; Min, S.; Yoon, S.-S.; Yun, Y.-M.; Kim, J.-T.; Cho, Y.S. Utility of ultra-rapid real-time PCR for detection and prevalence of Rickettsia spp. in ticks. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, P.; Paddock, C.D.; Socolovschi, C.; Labruna, M.B.; Mediannikov, O.; Kernif, T.; Abdad, M.Y.; Stenos, J.; Bitam, I.; Fournier, P.-E.; et al. Update on tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: A geographic approach. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 26, 657–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfving, K.; Olsen, B.; Bergström, S.; Waldenström, J.; Lundkvist, Å.; Sjöstedt, A.; Mejlon, H.; Nilsson, K. Dissemination of spotted fever Rickettsia agents in Europe by migrating birds. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteo, J.A.; Portillo, A. Tick-borne rickettsioses in Europe. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2012, 3, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionita, M.; Mitrea, I.L.; Pfister, K.; Hamel, D.; Silaghi, C. Molecular evidence for bacterial and protozoan pathogens in hard ticks from Romania. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 196, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharia, M.; Popescu, C.P.; Florescu, S.A.; Ceausu, E.; Raoult, D.; Parola, P.; Socolovschi, C. Rickettsia massiliae infection and SENLAT syndrome in Romania. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2016, 7, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheran, C.A.; Panciu, A.M.; Riciu, C.D.; Nedelcu, I.M.; Iacob, D.G.; Hristea, A. Identifying new areas of endemicity and risk factors for Rickettsia conorii subsp. conorii infection: Serosurvey in rural areas of Romania. Pathogens 2024, 13, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambrea, S.C.; Badiu, D.; Ionescu, C.; Penciu, R.; Pazara, L.; Mihai, C.M.; Cambrea, M.A.; Mihai, L. Boutonneuse fever in Southeastern Romania. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Peña, A. Ticks of Domestic Animals in the Mediterranean Region: A Guide to Identification of Species; University of Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2004; ISBN 978-84-96214-18-7. [Google Scholar]

- Dantas-Torres, F.; Latrofa, M.S.; Annoscia, G.; Giannelli, A.; Parisi, A.; Otranto, D. Morphological and genetic diversity of Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato from the New and Old Worlds. Parasites Vectors 2013, 6, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Peña, A.; Gray, J.S.; Kahl, O.; Lane, R.S.; Nijhoff, A.M. Research on the ecology of ticks and tick-borne pathogens—Methodological principles and caveats. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2013, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roux, V.; Rydkina, E.; Eremeeva, M.; Raoult, D. Citrate synthase gene comparison, a new tool for phylogenetic analysis and its application for the rickettsiae. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1997, 47, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenos, J.; Graves, S.R.; Unsworth, N.B. A highly sensitive and specific real-time PCR assay for the detection of spotted fever and typhus group rickettsiae. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005, 73, 1083–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omeragić, J.; Kapo, N.; Goletić, Š.; Softić, A.; Terzić, I.; Šabić, E.; Škapur, V.; Klarić Soldo, D.; Goletić, T. Investigation of tick-borne pathogens in Ixodes ticks from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Animals 2024, 14, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracasso, G.; Grillini, M.; Grassi, L.; Gradoni, F.; Rold, G.D.; Bertola, M. Effective methods of estimation of pathogen prevalence in pooled ticks. Pathogens 2023, 12, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bella, S.; Gambino, D.; Pepe, D.; Gentile, A.; Blanda, V.; Valenti, A.; Santangelo, F.; Ballatore, A.; Spina, G.; Barbaccia, G.; et al. Serosurvey of Rickettsia spp. and Ehrlichia canis in dogs from shelters in Sicily (Southern Italy). Pathogens 2024, 13, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backus, L.; Foley, J.; Chung, C.; Virata, S.; Zazueta, O.E.; López-Pérez, A. Tick-borne pathogens detected in sheltered dogs during an epidemic of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, a One Health challenge. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2023, 261, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randolph, S.E.; Gern, L.; Nuttall, P.A. Co-feeding ticks: Epidemiological significance for tick-borne pathogen transmission. Parasitol. Today 1996, 12, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tick Species | No. of Ticks | Females | Female Pools | Males | Male Pools | Nymphs | Nymph Pools |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. sanguineus s.l. | 585 | 232 | 58 | 324 | 32 | 29 | 4 |

| I. ricinus | 73 | 63 | 15 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| D. marginatus | 12 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| D. reticulatus | 60 | 30 | 9 | 30 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 730 | 333 | 88 | 368 | 40 | 29 | 4 |

| Tick Species | Pools Tested (n) | Positive Pools (n) | PPR (%) | Females (Pos/Total) | PPR (%) | Males (Pos/Total) | PPR(%) | Nymphs (Pos/Total) | PPR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. sanguineus s.l. | 94 | 88 | 93.6% | 54/58 | 93.1% | 30/32 | 93.8% | 4/4 | 100% |

| I. ricinus | 17 | 15 | 88.2% | 14/15 | 93.3% | 1/2 | 50% | - | |

| D. marginatus | 8 | 7 | 87.5% | 5/6 | 83.3% | 2/2 | 100% | - | |

| D. reticulatus | 13 | 13 | 100% | 9/9 | 100% | 4/4 | 100% | - | |

| Total | 132 | 123 | 93.2% | 82/88 | 93.2% | 37/40 | 92.5% | 4/4 | 100% |

| Tick Species | No. of Ticks | Pools Tested | Positive Pools | PPR (%) | PPR 95% CI | MIR (%) | MIR 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. sanguineus s.l. | 585 | 94 | 88 | 93.6 | 86.6–97.6 | 15.0 | 12.2–18.2 |

| I. ricinus | 73 | 17 | 15 | 88.2 | 63.6–98.5 | 20.5 | 12.0–31.6 |

| D. marginatus | 12 | 8 | 7 | 87.5 | 47.3–99.7 | 58.3 | 27.7–84.8 |

| D. reticulatus | 60 | 13 | 13 | 100 | 75.3–100 | 21.7 | 12.1–34.2 |

| Total | 730 | 132 | 123 | 93.2 | - | 16.8 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Andronic, B.-L.; Ivănescu, L.-M.; Martinescu, G.-V.; Mîndru, R.; Miron, L. Prevalence of Rickettsia spp. Infection in Ticks Collected from Shelter Dogs in Tulcea County, Romania. Pathogens 2026, 15, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010036

Andronic B-L, Ivănescu L-M, Martinescu G-V, Mîndru R, Miron L. Prevalence of Rickettsia spp. Infection in Ticks Collected from Shelter Dogs in Tulcea County, Romania. Pathogens. 2026; 15(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndronic, Bianca-Lavinia, Larisa-Maria Ivănescu, Gabriela-Victoria Martinescu, Raluca Mîndru, and Liviu Miron. 2026. "Prevalence of Rickettsia spp. Infection in Ticks Collected from Shelter Dogs in Tulcea County, Romania" Pathogens 15, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010036

APA StyleAndronic, B.-L., Ivănescu, L.-M., Martinescu, G.-V., Mîndru, R., & Miron, L. (2026). Prevalence of Rickettsia spp. Infection in Ticks Collected from Shelter Dogs in Tulcea County, Romania. Pathogens, 15(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010036