Babesia and Bartonella Species DNA in Blood and Enrichment Blood Cultures from People with Chronic Fatigue and Concurrent Neurological Symptoms

Abstract

1. Introduction

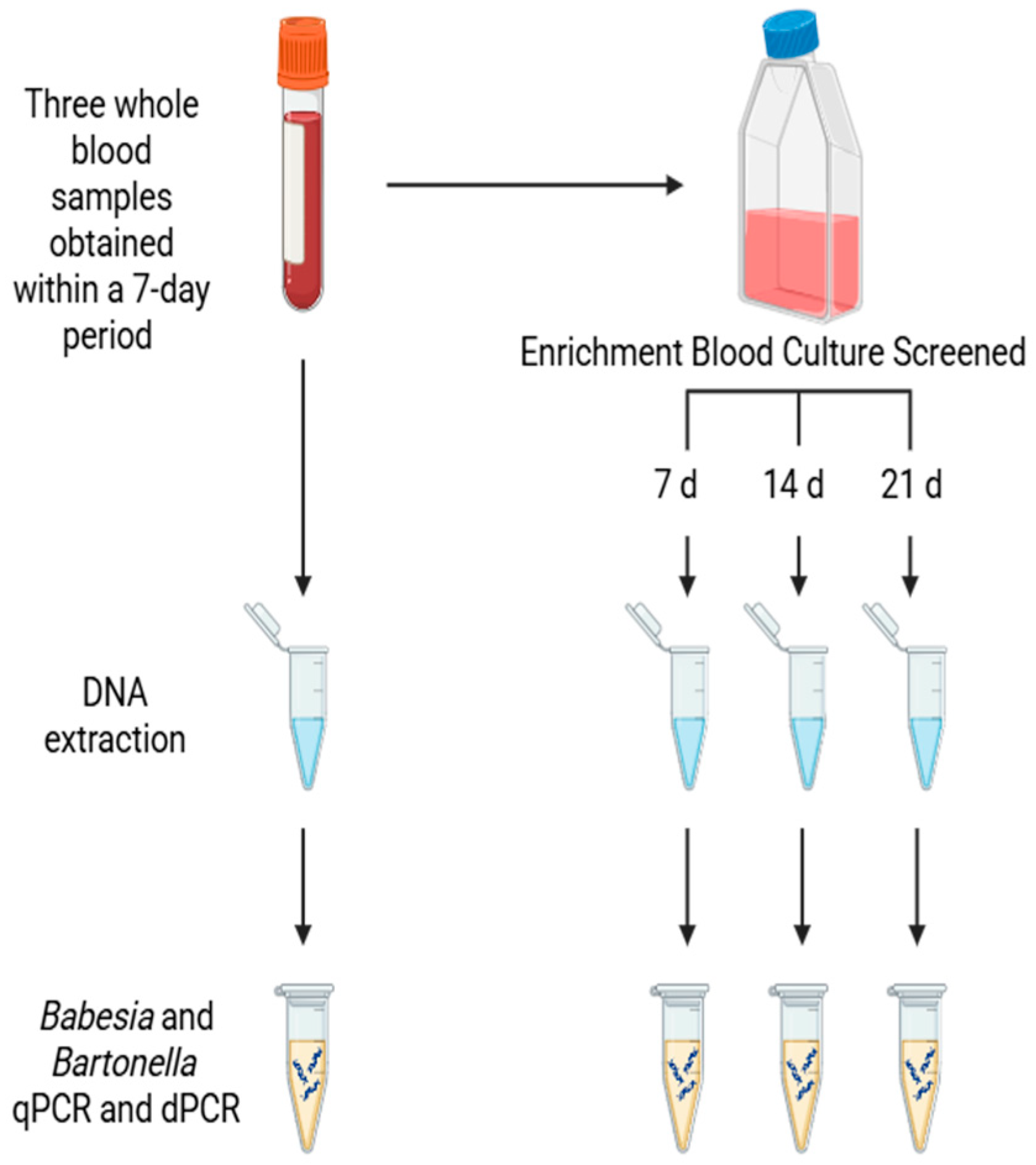

2. Patients and Methods

Study Population

3. Results

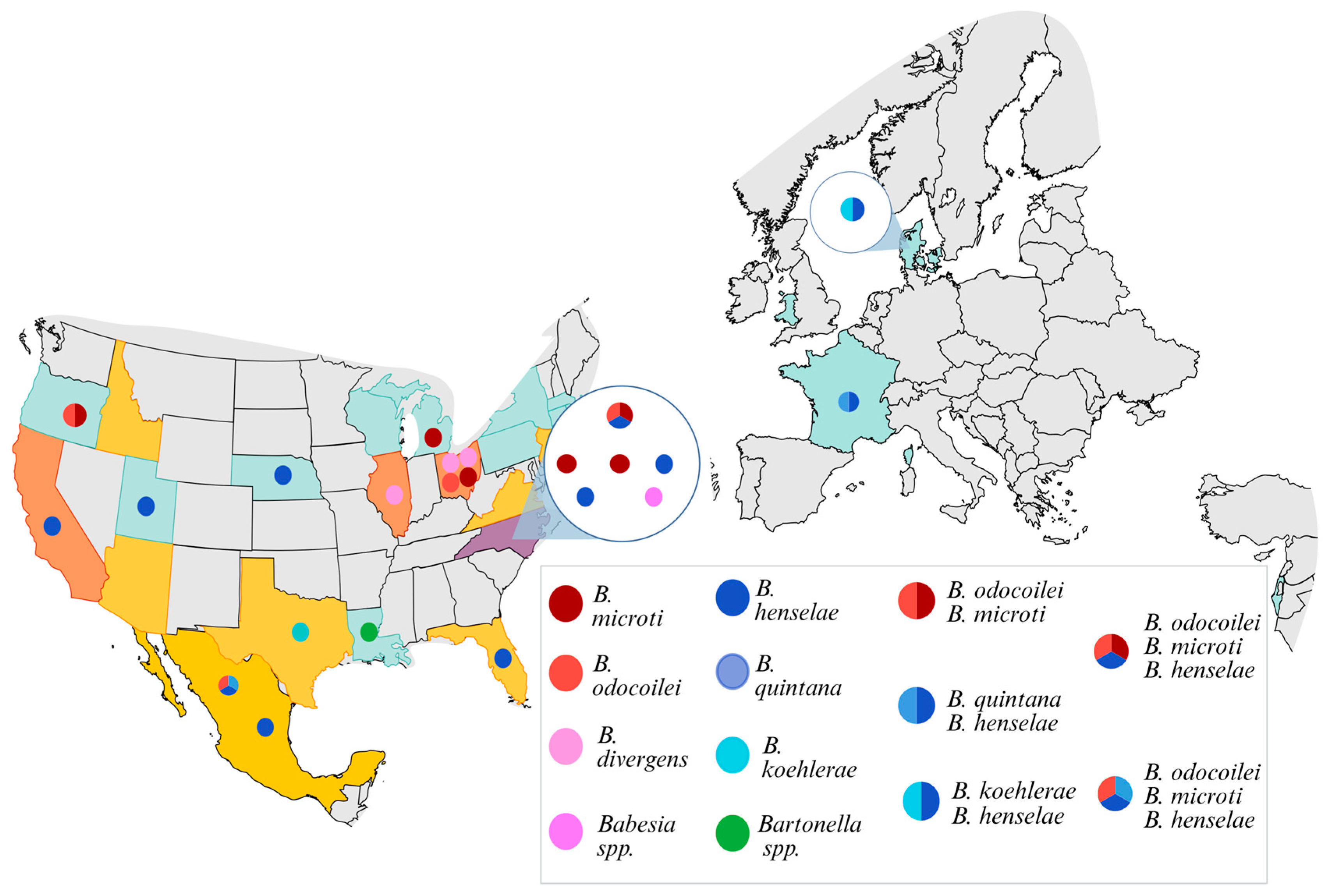

Molecular Testing Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Symptomatology and Pathogen Framework

4.2. Diagnostic Considerations in Pathogen Detection

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Maggi, R.G.; Robveille, C.; Kingston, E. Bartonella henselae, Babesia odocoilei and Babesia divergens-like MO-1 infection in the brain of a child with seizures, mycotoxin exposure and suspected Rasmussen’s encephalitis. J. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Dis. 2025, 17, 11795735251322456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Maggi, R.G.; Moore, C.O.; Robveille, C.; Greenberg, R.; Kingston, E. A One Health Zoonotic Vector Borne Infectious Disease Family Outbreak Investigation. Pathogens 2025, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, R.G.; Calchi, A.C.; Moore, C.O.; Kingston, E.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Human Babesia odocoilei and Bartonella spp. co-infections in the Americas. Parasites Vectors 2024, 17, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, E.D.; Winton, C.S.; Johnson, S.T.; Krysztof, D.E.; Townsend, R.L.; Foster, G.A.; Devine, P.; Molloy, P.; Brissette, E.; Berardi, V.P.; et al. Investigational screening for Babesia microti in a large repository of blood donor samples from nonendemic and endemic areas of the United States. Transfusion 2014, 54, 2226–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, R.F.; Cintra, M.L.; Barjas-Castro, M.L.; Del Negro, G.M.; Okay, T.S.; Velho, P.E. Blood donor infected with Bartonella henselae. Transfus. Med. 2010, 20, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.T.; Van Tassell, E.R.; Tonnetti, L.; Cable, R.G.; Berardi, V.P.; Leiby, D.A. Babesia microti real-time polymerase chain reaction testing of Connecticut blood donors: Potential implications for screening algorithms. Transfusion 2013, 53, 2644–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitassi, L.H.; de Paiva Diniz, P.P.; Scorpio, D.G.; Drummond, M.R.; Lania, B.G.; Barjas-Castro, M.L.; Gilioli, R.; Colombo, S.; Sowy, S.; Breitschwerdt, E.B.; et al. Bartonella spp. bacteremia in blood donors from Campinas, Brazil. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calchi, A.C.; Moore, C.O.; Bartone, L.; Kingston, E.; André, M.R.; Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Maggi, R.G. Development of Multiplex Assays for the Identification of Zoonotic Babesia Species. Pathogens 2024, 13, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.D.; Sajid, M.S.; Pascoe, E.L.; Foley, J.E. Detection of Babesia odocoilei in Humans with Babesiosis Symptoms. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todhunter-Brown, A.; Campbell, P.; Broderick, C.; Cowie, J.; Davis, B.; Fenton, C.; Markham, S.; Sellers, C.; Thomson, K. Recent research in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: An evidence map. Health Technol. Assess. 2025, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapra, A.; Bhandari, P. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Portillo, A.; Maggi, R.; Oteo, J.A.; Bradley, J.; Garcia-Alvarez, L.; San-Martin, M.; Roura, X.; Breitschwerdt, E. Bartonella spp. Prevalence (Serology, Culture, and PCR) in Sanitary Workers in La Rioja Spain. Pathogens 2020, 9, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazra, A. Using the confidence interval confidently. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, 4125–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantos, P.M.; Maggi, R.G.; Ferguson, B.; Varkey, J.; Park, L.P.; Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Woods, C.W. Detection of Bartonella species in the blood of veterinarians and veterinary technicians: A newly recognized occupational hazard? Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014, 14, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnittger, L.; Rodriguez, A.E.; Florin-Christensen, M.; Morrison, D.A. Babesia: A world emerging. Infect. Genet. Evol. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Evol. Genet. Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 1788–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Zheng, Y.C.; Jiang, J.F.; Jiang, R.R.; Jiang, B.G.; Wei, R.; Liu, H.B.; Huo, Q.B.; Sun, Y.; Chu, Y.L.; et al. Human Babesiosis Caused by a Babesia crassa-Like Pathogen: A Case Series. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2018, 67, 1110–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doderer-Lang, C.; Filisetti, D.; Badin, J.; Delale, C.; Clavier, V.; Brunet, J.; Gommenginger, C.; Abou-Bacar, A.; Pfaff, A.W. Babesia crassa-Like Human Infection Indicating Need for Adapted PCR Diagnosis of Babesiosis, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahfari, S.; Hofhuis, A.; Fonville, M.; van der Giessen, J.; van Pelt, W.; Sprong, H. Molecular Detection of Tick-Borne Pathogens in Humans with Tick Bites and Erythema Migrans, in the Netherlands. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0005042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssentongo, P.; Venugopal, N.; Zhang, Y.; Chinchilli, V.M.; Ba, D.M. Beyond Human Babesiosis: Prevalence and Association of Babesia Coinfection with Mortality in the United States, 2015–2022: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, ofae504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, S.; O’Bryan, J.; Zubair, A.S.; Rethana, M.; Moffarah, A.S.; Krause, P.J.; Farhadian, S.F. Neurologic Complications of Babesiosis, United States, 2011–2021. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, H.H.; Tanowitz, H.B.; Brutto, O.H.d. Neuroparasitology and Tropical Neurology; Elsevier: Edinburgh, UK; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aikawa, M.; Pongponratn, E.; Tegoshi, T.; Nakamura, K.; Nagatake, T.; Cochrane, A.; Ozaki, L.S. A study on the pathogenesis of human cerebral malaria and cerebral babesiosis. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1992, 87, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani-Brown, S.; Halperin, J.J.; Krause, P.J. Neurological manifestations of human babesiosis. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2013, 114, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, J.C.; Robveille, C.; Maggi, R.G.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Neurobartonelloses: Emerging from obscurity! Parasites Vectors 2024, 17, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guirguis, V.; Pupillo, F.; Rodrigues, S.; Walker, N.; Roth, H.; Liedig, C.E.; Maggi, R.G.; Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Frohlich, F. Bartonella spp. infection in people with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A pilot study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, S.; Robveille, C.; Maggi, R.G.; Lashnits, E.; Kingston, E.; Liedig, C.; Murray, L.; Fallon, B.A.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Bartonella species bacteremia in association with adult psychosis. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1388442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashnits, E.; Maggi, R.; Jarskog, F.; Bradley, J.; Breitschwerdt, E.; Frohlich, F. Schizophrenia and Bartonella spp. Infection: A Pilot Case-Control Study. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2021, 21, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheslock, M.A.; Embers, M.E. Human Bartonellosis: An Underappreciated Public Health Problem? Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedig, C.; Neupane, P.; Lashnits, E.; Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Maggi, R.G. Blood Supplementation Enhances Bartonella henselae Growth and Molecular Detection of Bacterial DNA in Liquid Culture. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0512622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukina, I.V.; Zelya, O.P. Extraordinary high level of propagation of Babesia divergens in severe human babesiosis. Parasitology 2022, 149, 1160–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, V.; Pal, A.C.; Singh, P.; Mamoun, C.B. Babesia duncani in Culture and in Mouse (ICIM) Model for the Advancement of Babesia Biology, Pathogenesis and Therapy. Bio Protoc. 2022, 12, e4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, L. Continuous in vitro propagation of Babesia microti. Infect. Immun. 2024, 92, e0048123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, R.G.; Mozayeni, B.R.; Pultorak, E.L.; Hegarty, B.C.; Bradley, J.M.; Correa, M.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Bartonella spp. bacteremia and rheumatic symptoms in patients from Lyme disease-endemic region. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, R.G.; Richardson, T.; Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Miller, J.C. Development and validation of a droplet digital PCR assay for the detection and quantification of Bartonella species within human clinical samples. J. Microbiol. Methods 2020, 176, 106022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Babesia ITS1 Target | Primers/Probe Designation | DNA Sequences |

|---|---|---|

| Babesia genus ITS1 region (550–650 bp) | Api18S rRNA-1690s | 5′ CTCCTACCGATCGAGTGATCCGGT 3′ |

| Api5.8S rRNA-20as | 5′ GCTGCGTCCTTCATCGTTGTGTGAG 3′ | |

| B. divergens ITS1 region (225 bp) | Bdivergens ITS1-25s | 5′ CTCGGCTTCGACATTTACGTTGTGTAAGCT 3′ |

| Bdivergens ITS1-150as | 5′ CAACTACAGTAGTTACACCGYAGTAARCATAC 3′ | |

| Probe Bdivergens ITS1-70 | 5′ HEX CTTTTKGTGGTTTCGTATTTGYCGTTG BHQ2 3′ | |

| B. duncani ITS1 region (170 bp) | Bduncani ITS1-1s | 5′ GTGTTTAAACCGCGCTTATGCGCAGGTC 3′ |

| Bduncani ITS1-130as | 5′ CTGCACTGGCGGGGTGAAAAGTAAC 3′ | |

| Probe Bduncani ITS1-80 | 5′ Cy5-TGGCTTTGCGGTTCGCCGTACGGCCCC-BHQ3 3′ | |

| B. microti TS1 region (185 bp) | Bmicroti ITS1-25s | 5′ TATCAGAGTTCTTTGTATCCCATTTGGGTTA 3′ |

| Bmicroti ITS1-160as | 5′ GAAAATACCTTGGGAGTGAGAACGCCCCGT 3′ | |

| Probe Bmicroti ITS1-70 | 5′ CalFluoRed590-AGAAGAGTGGCCTTGGACGTAG-BHQ2 3′ | |

| B. odocoilei ITS1 region (150 bp) | Bodoco ITS1-100s | 5′ CTGTTGCACTTTTGTGCTTGACGTTGT 3′ |

| Bodoco ITS1-255as | 5′ CAAGCGCAGGGATGGAAACGGA 3′ | |

| Probe Bodoco ITS1-200 | 5′ FAM-GGCCTCGTCATGGCGACGTGGT-BHQ1 3′ |

| Characteristic | Overall Study Population No. (%) | Babesia ONLY PCR Positive No. (%) | Bartonella PCR ONLY Positive No. (%) | Co-Infection No. (%) | Negative PCR No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 50 (100) | 10 (20) | 11 (22) | 2 (4) | 27 (54) | ||

| Sex | F | 36 (72) | 8 (80) | 7 (64) | 2 (100) | 19 (70) | |

| M | 14 (28) | 2 (20) | 4 (36) | 0 (0) | 8 (30) | ||

| Region of Residence | NE USA | 7 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (26) | |

| SE USA | 15 (30) | 3 (30) | 4 (36) | 1 (50) | 7 (26) | ||

| MW USA | 11 (22) | 6 (60) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 4 (15) | ||

| SW USA | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 2 (7) | ||

| W USA | 8 (16) | 1 (10) | 2 (18) | 0 (0) | 5 (19) | ||

| Other countries | 6 (12) | 0 (0) | 3 (27) | 1 (50) | 2 (7) | ||

| Duration of Illness | ≥6 months | 20 (40) | 4 (40) | 5 (45) | 0 (0) | 11 (41) | |

| ≥5 Years | 13 (26) | 2 (20) | 3 (27) | 1 (50) | 7 (26) | ||

| ≥10 Years | 17 (34) | 4 (40) | 3 (27) | 1 (50) | 9 (33) | ||

| Specialty Physician Visits | Y | 42 (84) | 5 (50) | 10 (91) | 2 (100) | 25 (93) | |

| N | 8 (16) | 5 (50) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 2 (7) | ||

| Type | ID | 22 (44) | 2 (20) | 5 (45) | 0 (0) | 15 (56) | |

| GI | 25 (50) | 3 (30) | 7 (64) | 0 (0) | 15 (56) | ||

| RH | 22 (44) | 1 (10) | 6 (54) | 0 (0) | 15 (56) | ||

| NE | 33 (66) | 4 (40) | 9 (82) | 2 (100) | 18 (67) | ||

| HE | 6 (12) | 1 (10) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 4 (15) | ||

| Total DNA Positive and Negative Participants | Difficulty Remembering | Headache | Insomnia | Anxiety | Irritability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Babesia (n = 10) | 8 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Bartonella (n = 11) | 10 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 9 |

| Babesia and Bartonella (n = 2) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Test Negative (n = 27) | 17 | 19 | 18 | 14 | 15 |

| Characteristic | Overall Study Population No. (%) | Babesia ONLY PCR Positive No. (%) | Bartonella PCR ONLY Positive No. (%) | Co-Infection No. (%) | Negative PCR No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Contact | Y | 47 (94) | 10 (100) | 11 (100) | 2 (100) | 24 (89) | |

| N | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (11) | ||

| Animal bites/scratches | Y | 39 (78) | 9 (90) | 8 (73) | 2 (100) | 20 (74) | |

| N | 11 (22) | 1 (10) | 3 (27) | 0 (0) | 7 (26) | ||

| Type | Dog | 31 (62) | 8 (80) | 5 (45) | 2 (100) | 16 (59) | |

| Cat | 34 (68) | 8 (80) | 7 (64) | 2 (100) | 17 (63) | ||

| Bird | 12 (24) | 4 (40) | 2 (18) | 2 (100) | 4 (15) | ||

| Horse | 6 (12) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 3 (11) | ||

| Rodent | 17 (34) | 5 (50) | 2 (18) | 1 (50) | 9 (33) | ||

| Insect exposure | Mosquitos | 47 (94) | 10 (100) | 10 (91) | 2 (100) | 26 (96) | |

| Tick | 41 (82) | 9 (90) | 9 (82) | 1 (50) | 22 (81) | ||

| Flea | 39 (78) | 10 (100) | 7 (64) | 2 (100) | 20 (74) | ||

| Biting Fly | 32 (64) | 7 (70) | 7 (64) | 1 (50) | 17 (63) | ||

| Lice | 23 (46) | 4 (40) | 4 (36) | 1 (50) | 14 (52) | ||

| Spiders | 36 (72) | 8 (80) | 7 (64) | 2 (100) | 19 (70) | ||

| Scabies | 6 (12) | 1 (10) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 5 (19) | ||

| Bedbugs | 6 (12) | 0 (0) | 2 (18) | 0 (0) | 4 (15) | ||

| Outdoor exposure | Hiking | 38 (76) | 9 (90) | 8 (73) | 1 (50) | 20 (74) | |

| Wildlife Rescue | 6 (12) | 3 (30) | 2 (18) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | ||

| Hunting | 5 (10) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 3 (11) | ||

| Other | 39 (78) | 9 (90) | 8 (73) | 1 (50) | 21 (78) | ||

| Participant | Species | Homology and Reference Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | B. odocoilei | 376/385 bp (97.7%) B. odocoilei AY339756 |

| 5 | B. odocoilei | 101/105 bp (96.2%) B. odocoilei AY339756 |

| B. microti | 103/103 bp (100%) B. microti GU230755 | |

| 8 | B. microti | 520/524 bp (99.2%) B. microti GU230755 |

| 11 | B. microti | 453/455 bp (99.6%) B. microti GU230755 |

| 19 | B. divergens MO-1 | 475/477 bp (99.6%) B. divergens PQ184854 |

| 22 | B. odocoilei | 123/124 bp (99.2%) B. odocoilei AY158711 |

| 24 | B. microti | 473/476 bp (99.4%) B. microti GU230755 |

| 25 | B. divergens MO-1 | 564/567 bp (99.5%) B. divergens PQ184854 |

| 27 | B. divergens MO-1 | 564/567 bp (99.5%) B. divergens PQ184854 |

| 30 | B. odocoilei | Probe based ^ |

| B. microti | Probe based ^ | |

| 40 | Babesia sp. * | 50/50 bp * (100%) B. odocoilei AY339756 |

| 41 | B. microti | 119/121 bp (98.4%) B. microti GU230755 |

| Participant | Species | Homology and Reference Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | B. henselae | 126/127 bp (99.2%) B. henselae SA2 AF369529 |

| 4 | B. henselae | 138/138 bp (100%) B. henselae SA2 AF369529 |

| B. quintana | 128/128 (100%) B. quintana Oklahoma AF368391 | |

| 5 | B. henselae | 140/140 bp (100%) B. henselae SA2 AF369529 |

| 6 | B. henselae | 135/135 bp (100%) B. henselae SA2 AF369529 |

| 14 | B. quintana | 129/129 bp (100%) B quintana Oklahoma AF368391 |

| 15 | B. henselae | Probe based ^ |

| 17 | B. henselae | 128/128 bp (100%) B. henselae SA2 AF369529 |

| 18 | B. koehlerae | 110/110 bp (100%) B. koehlerae AF312490 |

| 31 | B. henselae | 122/123 bp (99.2%) B. henselae SA2 AF369529 |

| 43 | B. henselae | Probe-based ^ |

| 44 | B. henselae | Probe-based ^ |

| 45 | B. henselae | 135/135 bp (100%) B. henselae SA2 AF369529 |

| 46 | B. spp. * | 87/87 (100%) Bartonella spp. |

| Sample Source | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | Blood Cult 7 Days | Blood Cult 14 Days | Blood Cult 21 Days | |

| B. odocoilei | 4 | - | - | - |

| B. microti | 1 | 5 | - | 1 |

| B. divergens | 1 | - | 2 | 1 |

| Babesia spp. | - | - | 1 | - |

| Sample Source | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | Blood Cult 7 Days | Blood Cult 14 Days | Blood Cult 21 Days | |

| B. henselae | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| B. quintana | - | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| B. koehlerae | 1 | - | - | - |

| Bartonella new spp. | 1 | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Maggi, R.G.; Bush, J.C.; Kingston, E. Babesia and Bartonella Species DNA in Blood and Enrichment Blood Cultures from People with Chronic Fatigue and Concurrent Neurological Symptoms. Pathogens 2026, 15, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010002

Breitschwerdt EB, Maggi RG, Bush JC, Kingston E. Babesia and Bartonella Species DNA in Blood and Enrichment Blood Cultures from People with Chronic Fatigue and Concurrent Neurological Symptoms. Pathogens. 2026; 15(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleBreitschwerdt, Edward B., Ricardo G. Maggi, Janice C. Bush, and Emily Kingston. 2026. "Babesia and Bartonella Species DNA in Blood and Enrichment Blood Cultures from People with Chronic Fatigue and Concurrent Neurological Symptoms" Pathogens 15, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010002

APA StyleBreitschwerdt, E. B., Maggi, R. G., Bush, J. C., & Kingston, E. (2026). Babesia and Bartonella Species DNA in Blood and Enrichment Blood Cultures from People with Chronic Fatigue and Concurrent Neurological Symptoms. Pathogens, 15(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010002