Autonomic Dysfunction in Patients with Acute Infection with Coxiella burnetii

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Enrollment

2.2. Ethnic Approval

2.3. Study Protocol

2.3.1. Cardiovascular Autonomic Reflex Tests (CART)

2.3.2. Short-Term Beat-to-Beat Analysis

2.3.3. 24 h Holter ECG Monitoring

2.3.4. Head-Up Tilt Test (HUTT)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Loscalzo, J.; Fauci, A.S.; Kasper, D.L.; Hauser, S.L.; Longo, D.L.; Jameson, J.L. (Eds.) Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 21st ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2022; 1p. [Google Scholar]

- España, P.P.; Uranga, A.; Cillóniz, C.; Torres, A. Q Fever (Coxiella burnetii). Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 41, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunette, G.W. Q Fever [Internet]. Medscape. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/227156-overview (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Lim, J.A.; Kim, J.M.; Lee, S.T.; Jung, K.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, S.K.; Chu, K. Brainstem encephalitis caused by Coxiella burnetii. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 21, 699–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernit, E.; Pouget, J.; Janbon, F.; Dutronc, H.; Martinez, P.; Brouqui, P.; Raoult, D. Neurological involvement in acute Q fever: A report of 29 cases and review of the literature. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002, 162, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofteridis, D.P.; Mazokopakis, E.E.; Tselentis, Y.; Gikas, A. Neurological complications of acute Q fever infection. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 19, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, L.; Dyer, A.H.; Jones, K.; Dunne, J.; Mooney, A.; Gaffney, F.; O’Connor, L.; Leavy, D.; O’Brien, K.; Dowds, J.; et al. Persistent fatigue following SARS-CoV-2 infection is common and independent of severity of initial infection. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, L.; Valencia, I.J.; Garvert, D.W.; Montoya, J.G. Onset Patterns and Course of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes Rivera, M.; Mastronardi, C.; Silva-Aldana, C.T.; Arcos-Burgos, M.; Lidbury, B.A. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics 2019, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Słomko, J.; Estévez-López, F.; Kujawski, S.; Zawadka-Kunikowska, M.; Tafil-Klawe, M.; Klawe, J.J.; Morten, K.J.; Szrajda, J.; Murovska, M.; Newton, J.L.; et al. Autonomic Phenotypes in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) Are Associated with Illness Severity: A Cluster Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milovanovic, B.; Markovic, N.; Petrovic, M.; Zugic, V.; Ostojic, M.; Rankovic-Nicic, L.; Bojic, M. Assessment of Autonomic Nervous System Function in Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Post-COVID-19 Syndrome Presenting with Recurrent Syncope. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorowski, A.; Fanciulli, A.; Raj, S.R.; Sheldon, R.; Shibao, C.A.; Sutton, R. Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in post-COVID-19 syndrome: A major health-care burden. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, B.L.; Chung, T.; Rowe, P.C.; Aucott, J. Dysautonomia following Lyme disease: A key component of post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome? Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1344862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, P.; Felsenstein, D.; Mao, C.; Octavien, N.R.; Zubcevik, N. Association of small fiber neuropathy and post treatment Lyme disease syndrome. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanovic, B.; Markovic, N.; Petrovic, M.; Zugic, V.; Ostojic, M.; Bojic, M. Cross-Sectional Study Evaluating the Role of Autonomic Nervous System Functional Diagnostics in Differentiating Post-Infectious Syndromes: Post-COVID Syndrome, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and Lyme Disease. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, R.W.; Notkins, A.L. Viral infections of the autonomic nervous system and its target organs: Pathogenetic mechanisms. Med. Hypotheses 1977, 3, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, R.W.; Katz, B.J.; Notkins, A.L. Latent infection of the peripheral ANS with herpes simplex virus. Nature 1975, 257, 686–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasmani, R.; Elkambergy, H.; Okoli, K. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infect. Dis. Clin. Pract. 2009, 17, 342–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieknik, J.R.; Bertke, A.S.; Krause, P.R. Herpes Simplex Virus 2 in Autonomic Ganglia: Evidence for Spontaneous Reactivation. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00227-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanriverdi, O.; Askin, L.; Askin, H.S.; Turkmen, S. Investigation of Heart Rate Variability and Ventricular Repolarization Indexes in Brucella Patients with Palpitations. Cor Vasa 2024, 66, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (or Encephalopathy)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Diagnosis and Management (NG206); NICE: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng206 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Brignole, M.; Moya, A.; de Lange, F.J.; Deharo, J.C.; Elliott, P.M.; Fanciulli, A.; Fedorowski, A.; Furlan, R.; Kenny, R.A.; Martín, A.; et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 1883–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.R.; Fedorowski, A.; Sheldon, R.S. Diagnosis and management of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2022, 194, E378–E385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.R.; Guzman, J.C.; Harvey, P.; Richer, L.; Schondorf, R.; Seifer, C.; Thibodeau-Jarry, N.; Sheldon, R.S. Canadian Cardiovascular Society Position Statement on Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) and Related Disorders of Chronic Orthostatic Intolerance. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020, 36, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 Condition (Long COVID). Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Ewing, D.J.; Clarke, B.F. Diagnosis and management of diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1982, 285, 916–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavere, F.; Bosello, G.; Fedele, D.; Cardone, C.; Ferri, M. Diagnosis and management of diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1983, 287, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratze, G.; Fortin, J.; Holler, A.; Grasenick, K.; Pfurtscheller, G.; Wach, P.; Schönegger, J.; Kotanko, P.; Skrabal, F. A software package for non-invasive, real-time beat-to-beat monitoring of stroke volume, blood pressure, total peripheral resistance and for assessment of autonomic function. Comput. Biol. Med. 1998, 28, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parati, G.; Frattola, A.; Di Rienzo, M.; Castiglioni, P.; Pedotti, A.; Mancia, G. Effects of aging on 24-h dynamic baroreceptor control of heart rate in ambulant subjects. Am. J. Physiol. 1995, 268, H1606–H1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, A.P.; Theodorakis, G.; Vardas, P.; Sutton, R. Methodology of head-up tilt testing in patients with unexplained syncope. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1991, 17, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pape, M.; Mandraveli, K.; Arvanitidou-Vagiona, M.; Nikolaidis, P.; Alexiou-Daniel, S. Q fever in northern Greece: Epidemiological and clinical data from 58 acute and chronic cases. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2009, 15, 150–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartzell, J.D.; Wood-Morris, R.N.; Martinez, L.J.; Trotta, R.F. Q fever: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2008, 83, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Jang, S.Y.; Yim, H.R.; On, Y.K.; Huh, J.; Shin, D.H.; Kim, J.H. Gender Difference in Patients with Recurrent Neurally Mediated Syncope. Yonsei Med. J. 2010, 51, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faro, M.; Sàez-Francás, N.; Castro-Marrero, J.; Aliste, L.; Fernández De Sevilla, T.; Alegre, J. Diferencias de género en pacientes con síndrome de fatiga crónica. Reumatol. Clínica 2016, 12, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raijmakers, R.P.H.; Koeken, V.A.C.M.; Jansen, A.F.M.; Keijmel, S.P.; Roerink, M.E.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Netea, M.G.; van der Meer, J.W.M.; Bleeker-Rovers, C.P. Cytokine profiles in patients with Q fever fatigue syndrome. J. Infect. 2019, 78, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellocchi, C.; Carandina, A.; Montinaro, B.; Targetti, E.; Furlan, L.; Rodrigues, G.D.; Tobaldini, E.; Montano, N. The Interplay between Autonomic Nervous System and Inflammation across Systemic Autoimmune Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanovic, B.; Markovic, N.; Petrovic, M.; Zugic, V.; Ostojic, M.; Dragicevic-Antonic, M.; Bojic, M. A New Approach to the Etiology of Syncope: Infection as a Cause. Viruses 2025, 17, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.S.; Bae, P.K.; Jeong, H.W.; Son, B.R.; Shin, K.S. Serological Evidence of Coxiella burnetii and SARS-CoV-2 Co-infection: A Case Report. Ann. Lab. Med. 2021, 41, 510–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalak, K.P.; Michalak, A.Z.; Brenk-Krakowska, A. Acute COVID-19 and Long COVID syndrome–molecular implications for therapeutic strategies—Review. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1582783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygmunt, A.; Stanczyk, J. Methods of evaluation of autonomic nervous system function. Arch. Med. Sci. 2010, 6, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilz, M.L.; Dütsch, M. Quantitative studies of autonomic function. Muscle Nerve 2006, 33, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körei, A.E.; Kempler, M.; Istenes, I.; Vági, O.E.; Putz, Z.; Horváth, V.J.; Keresztes, K.; Lengyel, C.; Tabák, Á.; Spallone, V.; et al. Why not to use the handgrip test in the assessment of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy among patients with diabetes mellitus? Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2017, 15, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Jin, H.; Wang, M.; Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; He, Q.; Chang, J.; Hong, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, D.; et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, K.C.; Silva, C.C.; Trindade, S.D.S.; Santos, M.C.S.; Rocha, R.S.B.; Vasconcelos, P.F.D.C.; Quaresma, J.A.S.; Falcão, L.F.M. Reduction of Cardiac Autonomic Modulation and Increased Sympathetic Activity by Heart Rate Variability in Patients with Long COVID. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 862001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian, M.; Golchoobian, R. Potential autonomic nervous system dysfunction in COVID-19 patients detected by heart rate variability is a sign of SARS-CoV-2 neurotropic features. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 8131–8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanovic, B.; Djajic, V.; Bajic, D.; Djokovic, A.; Krajnovic, T.; Jovanovic, S.; Verhaz, A.; Kovacevic, P.; Ostojic, M. Assessment of Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction in the Early Phase of Infection with SARS-CoV-2 Virus. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 640835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, B.K.; Shah, M.; Monro, J.A.; Kingston, M.C.; Julu, P.O. Respiratory modulation of cardiac vagal tone in Lyme disease. World J. Cardiol. 2014, 6, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Gao, Z.; Blaha, C.; Herr, M.D.; Mast, J.; Sinoway, L.I. Distension of central great vein decreases sympathetic outflow in humans. Am. J. Physiol-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2013, 305, H378–H385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, P.A.; Benarroch, E.E. Clinical Autonomic Disorders, 3rd ed.; Wolters Kluwer Health: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008; 808p. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.P.; Koenig, J.; Carnevali, L.; Sgoifo, A.; Jarczok, M.N.; Sternberg, E.M.; Thayer, J.F. Heart rate variability and inflammation: A meta-analysis of human studies. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 80, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausenloy, D.J.; Arhi, C.; Chandra, N.; Franzen-McManus, A.-C.; Meyer, A.; Sutton, R. Blood pressure oscillations during tilt testing as a predictive marker of vasovagal syncope. Europace 2009, 11, 1696–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narasimhan, B.; Calambur, A.; Moras, E.; Wu, L.; Aronow, W. Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome in COVID-19: A Contemporary Review of Mechanisms, Clinical Course and Management. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2023, 19, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Circulation 1996, 93, 1043–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwalm, T. Modern Tilt Table Testing and Non-Invasive Monitoring: Traditional and Innovative Applications in Theory and Practice; ABW Wissenschaftsverlag: Berlin, Germany, 2006; 151p. [Google Scholar]

- Mooren, F.C.; Böckelmann, I.; Waranski, M.; Kotewitsch, M.; Teschler, M.; Schäfer, H.; Schmitz, B. Autonomic dysregulation in long-term patients suffering from Post-COVID-19 Syndrome assessed by heart rate variability. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, K.J. The inflammatory reflex. Nature 2002, 420, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaz, B.; Sinniger, V.; Pellissier, S. Anti-inflammatory properties of the vagus nerve: Potential therapeutic implications of vagus nerve stimulation. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 5781–5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komaroff, A.L.; Lipkin, W.I. Insights from myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome may help unravel the pathogenesis of postacute COVID-19 syndrome. Trends Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlov, V.A.; Tracey, K.J. Neural regulation of immunity: Molecular mechanisms and clinical translation. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Coxiella Group N = 100 | Control Group N = 56 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs.) (mean ± SD) | 45 ± 15.3 | 41 ± 10.7 | 0.084 a |

| Female (n, %) | 80 (80%) | 37 (66.1%) | 0.054 b |

| ME/CFS (n, %) | 35 (35%) | / | |

| PCS (n, %) | 5 (5%) | / | |

| Previous syncope (n, %) | 59 (59%) | / | |

| HTA (n, %) | 2 (2%) | / | |

| DM (n, %) | 0 | / | |

| GERD (n, %) | 4 (4%) | / | |

| Pneumonia in the previous year (n, %) | 3 (3%) | / |

| Coxiella Group N = 100 | Control Group N = 56 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

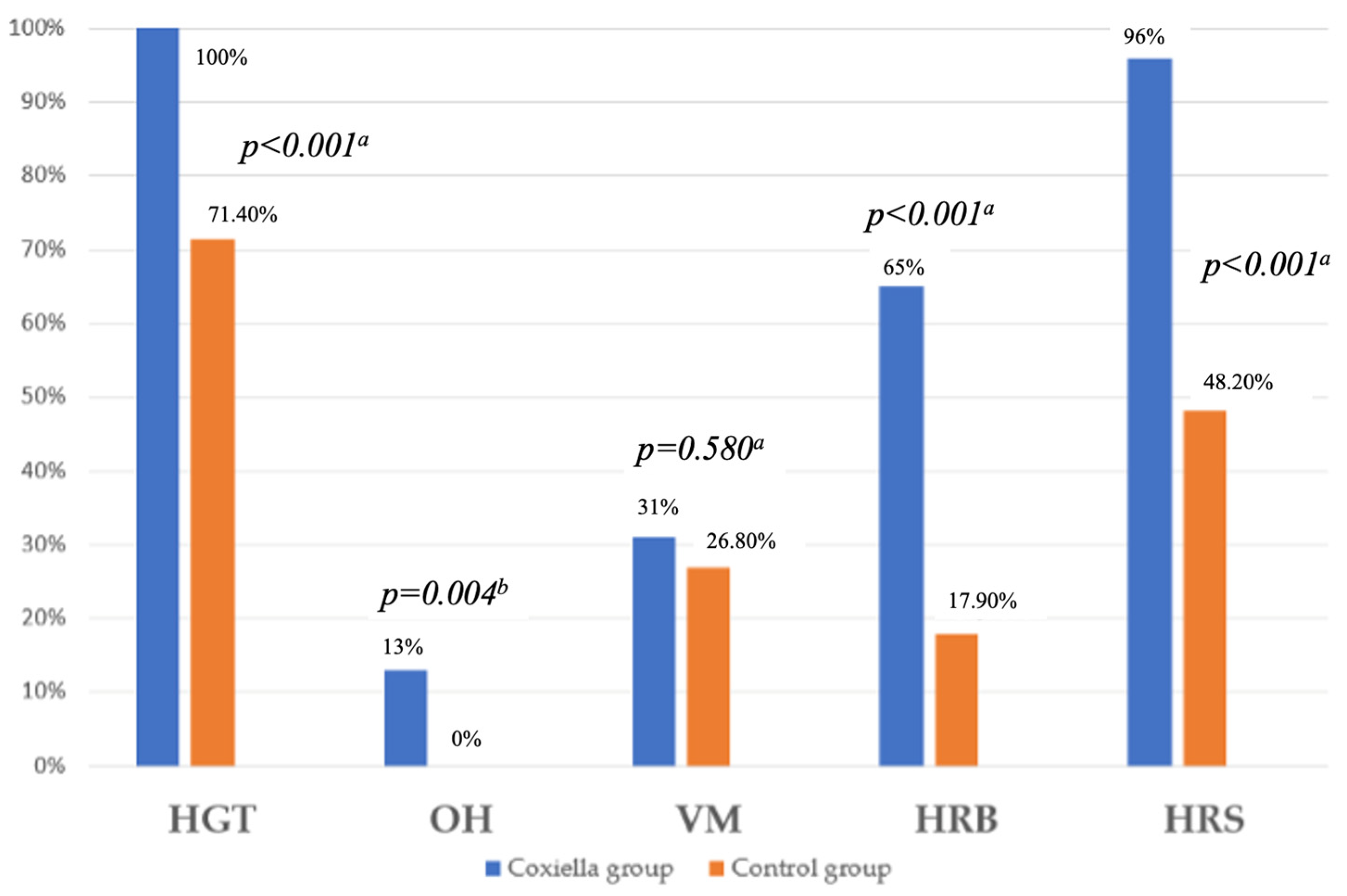

| HGT (n, %) | 100 (100%) | 40 (71.4%) | <0.001 a |

| OH (n, %) | 13 (13%) | 0 | 0.004 b |

| DS (n, %) | 100 (100%) | 40 (71.4%) | <0.001 a |

| VM (n, %) | 31 (31%) | 15 (26.8%) | 0.580 a |

| HRB (n, %) | 65 (65%) | 10 (17.9%) | <0.001 a |

| HRS (n, %) | 96 (96%) | 27 (48.2%) | <0.001 a |

| Definite DP (n, %) | 72 (72%) | 10 (17.9%) | <0.001 a |

| Score of AN (mead ± SD) | 6.5 ± 1.5 | 4.3 ± 1.6 | <0.001 c |

| Coxiella Group N = 100 | Control Group N = 56 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (bpm) (Mdn (IQR)) | 80.3 (58.9–96) | 69.9 (63.8–75.4) | 0.015 a |

| SBP (mmHg) (mean ± SD) | 110.2 ± 14.1 | 113.5 ± 11.7 | 0.399 b |

| DBP (mmHg) (mean ± SD) | 71.7 ± 9.2 | 75.8 ± 9.1 | 0.167 b |

| LF (nu) (mean ± SD) | 59.9 ± 16.8 | 60.6 ± 16.5 | 0.908 b |

| PSD (ms2) (Mdn (IQR)) | 499 (249–2502) | 1378 (649–3356) | 0.106 b |

| VLF (ms2) (Mdn (IQR)) | 117 (64–396) | 300 (152–734) | 0.058 b |

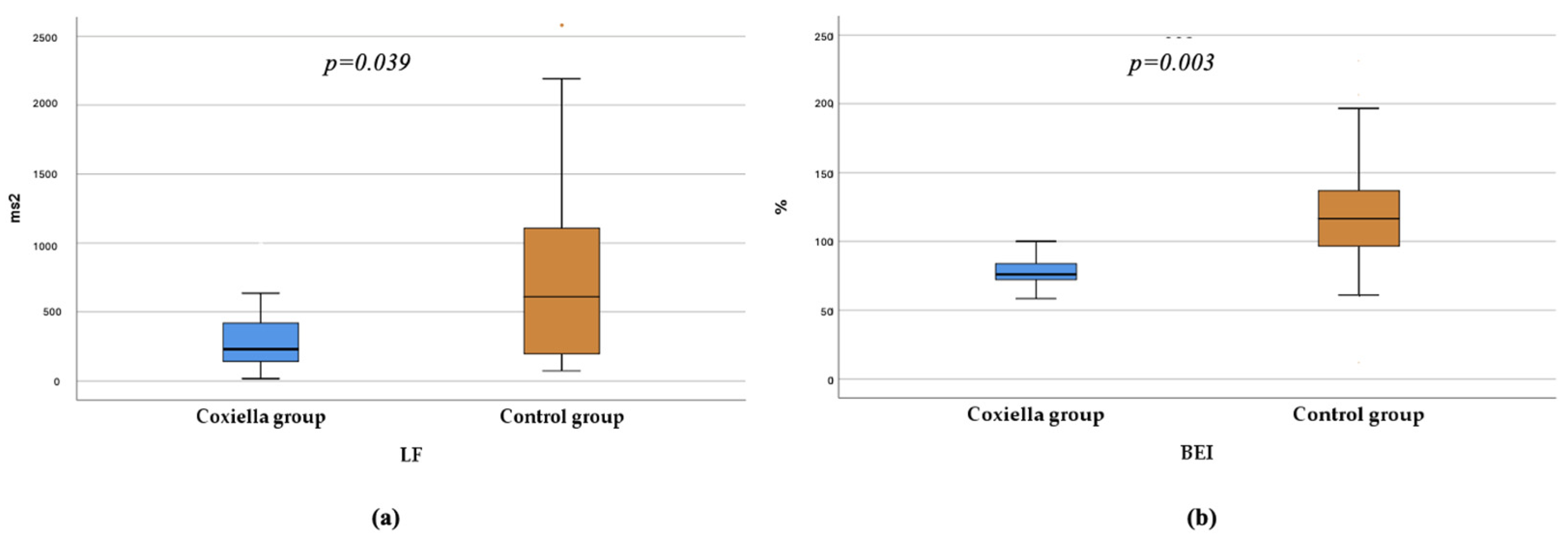

| LF (ms2) (Mdn (IQR)) | 230 (128–450) | 611 (195–1134) | 0.039 b |

| HF (ms2) (Mdn (IQR)) | 170 (33–445) | 310 (122–736) | 0.194 b |

| LF/HF (nu) (Mdn (IQR)) | 1.5 (1.2–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.641 b |

| LF/HF (ms2) (Mdn (IQR)) | 1.2 (0.6–1.7) | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) | 0.415 b |

| BRS (ms/mmHg) (Mdn (IQR)) | 11.4 (7–16.1) | 15.3 (11.5–20.1) | 0.080 b |

| BEI (%) (Mdn (IQR)) | 76 (65.3–91.99) | 116.5 (95.6–137.9) | 0.003 b |

| Coxiella Group N = 100 | Control Group N = 56 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (bpm) (mean ± SD) | 77.2 ± 6.8 | 75.8 ± 7.5 | 0.421 a |

| SDNN (ms) (mean ± SD) | 145.2 ± 32.1 | 152.6 ± 36.4 | 0.397 a |

| RMSSD (ms) (Mdn (IQR)) | 35 (31–58.5) | 33.5 (25.8–46) | 0.167 b |

| PNN50 (%)(Mdn (IQR)) | 10 (3.5–16.5) | 10 (5.5–18) | 0.908 b |

| TP (ms2) (Mdn (IQR)) | 2979 (2259.3–4008.3) | 3676 (2778.7–5085.2) | 0.106 b |

| VLF (ms2) (Mdn (IQR)) | 2009.9 (1432.8–2553.6) | 2436.5 (1741.5–3471.5) | 0.058 b |

| LF (ms2) (Mdn (IQR)) | 846.6 (452.2–1086.5) | 878.8 (649.8–1137.8) | 0.360 b |

| HF (ms2) (Mdn (IQR)) | 264 (158.9–335.9) | 265.1 (179–429.4) | 0.194 b |

| LF/HF (ms2) (Mdn (IQR)) | 3.4 (2.4–4.6) | 2.9 (2.1–4.5) | 0.641 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Milovanović, B.; Marković, N.; Ristanović, E.; Atanasievska Kujović, S.; Đorđevski, N.; Petrovic, M.; Milošević, M.; Bulatovic, S.; Bojić, M. Autonomic Dysfunction in Patients with Acute Infection with Coxiella burnetii. Pathogens 2026, 15, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010003

Milovanović B, Marković N, Ristanović E, Atanasievska Kujović S, Đorđevski N, Petrovic M, Milošević M, Bulatovic S, Bojić M. Autonomic Dysfunction in Patients with Acute Infection with Coxiella burnetii. Pathogens. 2026; 15(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilovanović, Branislav, Nikola Marković, Elizabeta Ristanović, Sonja Atanasievska Kujović, Nikoleta Đorđevski, Masa Petrovic, Milica Milošević, Sulin Bulatovic, and Milovan Bojić. 2026. "Autonomic Dysfunction in Patients with Acute Infection with Coxiella burnetii" Pathogens 15, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010003

APA StyleMilovanović, B., Marković, N., Ristanović, E., Atanasievska Kujović, S., Đorđevski, N., Petrovic, M., Milošević, M., Bulatovic, S., & Bojić, M. (2026). Autonomic Dysfunction in Patients with Acute Infection with Coxiella burnetii. Pathogens, 15(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010003