Concurrent Leydig and Sertoli Cell Tumors Associated with Testicular Mycosis in a Dog: A Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Discussion and Conclusions

- –

- Clinical analysis and laboratory test results: Morphological, biochemical, serological, and other;

- –

- Collection of various biological materials from patients for mycological evaluation: Blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and fluids from the pleural cavity, peritoneum, and joints; material from cysts, abscesses, and puncture of the paranasal sinuses; samples from the lower respiratory tract (e.g., sputum); samples obtained during surgical procedures, endoscopy, or fine-needle aspiration biopsy; swabs from the oral cavity, pharynx, nasal cavities, and larynx; content from the genital organs, for example, from the urethra, urine, and others;

- –

- Direct techniques are the simplest diagnostic method, and sometimes, they are decisive, such as in Pneumocystis carinii or Rhinosporidium seeberi infections;

- –

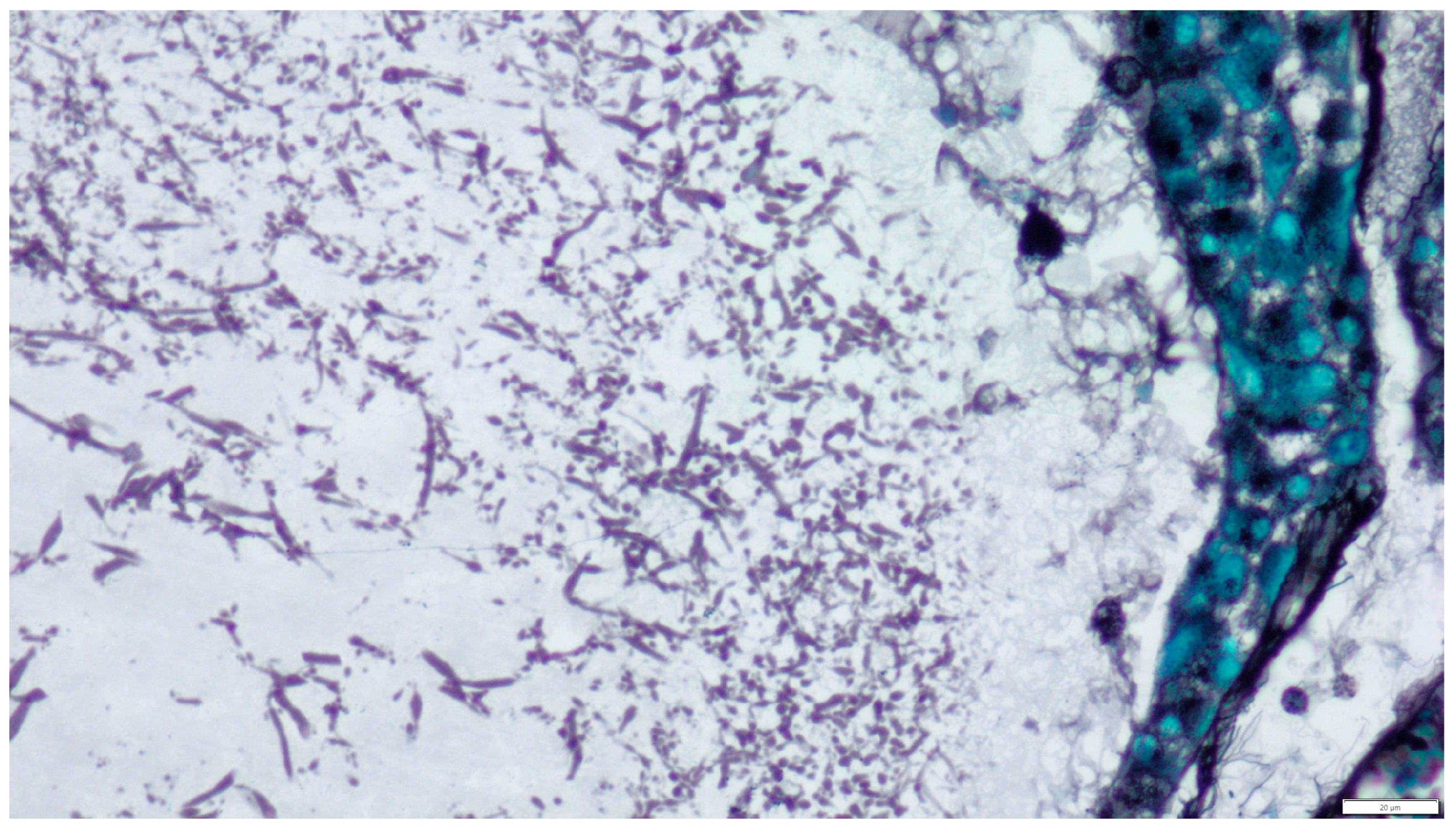

- Stained preparations: smears, histopathological preparations;

- –

- Cultures—Material collected for testing for the presence of fungi is inoculated onto liquid or solid media—containing protein, carbohydrates, and other components—directly in the amount of 0.5–1.5 cm3. Tissues or biopsy specimens are homogenized or ground by shaking with sterile beads; materials collected during biopsy are simultaneously inoculated onto solid or liquid Sabouraud media or broth agar;

- –

- Other techniques include fluorescence, immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, and in situ hybridization. Immunohistochemical tests with monoclonal antibodies (WF-AF-1, EB-A1), immunofluorescence, and in situ hybridization are also used in diagnostics to determine the genus and species, especially in cases where it is not possible to culture fungi [3,13,14,16].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HE | Hematoxylin and eosin (stain) |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HPF | High-power field |

| ICT | Interstitial cell tumor |

| SCT | Sertoli cell tumor |

| SEM | Seminoma |

References

- Singer, A.J.; Kubak, B.; Anders, K.H. Aspergillosis of the Testis in a Renal Transplant Recipient. Urology 1998, 51, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosejl-Kajtna, M.; Kandus, A.; Rott, T.; Zer, S.; Zupan, I.; Kosejl, M.; Bren, A. Aspergillus infection in immunocompromised patients. Transplant. Proc. 2001, 33, 2176–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D.W. Aspergillosis: Diagnosis and treatement. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 1996, 6, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczek, W.; Ratajczak, K.; Janeczek, M. Treatment of canine nasal aspergillosis with postoperative application of itraconasol. Med. Weter. 2004, 60, 1303–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Salas, A.J.; Aquino-Matus, J.E. Cesar Emmanuel-Guadarrama CE. Localized genitourinary tract Aspergillus infection in an immunocompetent patient: Bladder and epidydimal aspergillosis. Urol. Case Rep. 2022, 42, 102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Hernández, C.J.; Jesús-Silva, A.; Toussaint-Caire, S.; Arenas, R. Disseminated Sporotrichosis With Cutaneous and Testicular Involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014, 105, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klett, D.E.; Hong, Y.M. Coccidioidomycosis of the Testis and Epididymis. Open J. Urol. 2013, 3, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lin, C.Y.; Jwo, S.C.; Lin, C.C. Primary testicular actinomycosis mimicking metastatic tumor. Int. J. Urol. 2005, 12, 519–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrik, D.; Hoare, D.; MacGillivray, M.; Ricciuto, D. Blastomycosis of the scrotum: Not a fun guy. Urol. Case Rep. 2025, 58, 102907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totten, A.K.; Ridgway, M.D.; Sauberli, D.S. Blastomyces dermatitidis prostatic and testicular infection in eight dogs (1992–2005). J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2011, 47, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tell, L.A. Aspergillosis in mammals and birds: Impact on veterinary medicine. Med. Mycol. 2005, 43 (Suppl. S1), S71–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capilla, J.; Clemons, K.V.; Stevens, D.A. Animal models: An important tool in mycology. Med. Mycol. 2007, 45, 657–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venyo, A.K. Aspergillosis of the Genito-Urinary tract and Kidney Including: The Penis, Scrotum, Testis, Urinary Bladder, Ureter, Renal Pelvis, Vulva, Vagina, Uterus, Fallopian Tubes, the Ovaries, as well as the Kidney: A Review and Update. Int. J. Clin. Case Stud. 2023, 2, 3. Available online: https://www.clinicsearchonline.org/article/aspergillosis-of-the-genito-urinary-tract-and-kidney-including-the-penis-scrotum-testis-urinary-bladder-ureter-renal-pelvis-vulva-vagina-uterus-fallopian-tubes-the-ovaries-as-well-as-the-kidney-a-review-and-update (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Wise, G.J.; Silver, D.A. Fungal infections of the genitourinary system. J. Urol. 1993, 149, 1377–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemieniuch, M.; Skarzyński, D.J.; Kozdrowski, R. Aspergillosis of a dog genital tract—Case reports. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2009, 112, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.T.; Frazho, J.K.; Randell, S.C. A novel case of canine disseminated aspergillosis following mating. Can. Vet. J. 2012, 53, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ando, T.; Naito, M. First case of synchronous Leydig cell tumor and spermatocytic tumor in the unilateral testis. Urol. Case Rep. 2024, 53, 102648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, C.; Bertolotto, M.; Hawthorn, B.R.; Antonelli, C.T.; Sidhu, P.S.; Ascenti, G.; Nikolaidis, P.; Dudea, S.; Toncini, C.; Derchi, L.E. Multiple, Synchronous Lesions of Differing Histology Within the Same Testis: Ultrasonographic and Pathologic Correlations. Urology 2018, 121, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrlich, Y.; Konichezky, M.; Yossepowitch, O.; Baniel, J. Multifocality in Testicular Germ Cell Tumors. J. Urol. 2009, 181, 114–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favilla, V.; Russo, G.I.; Spitaleri, F.; Urzì, D.; Garau, M.; Madonia, M.; Saita, A.; Pirozzi Farina, F.; La Vignera, S.; Condorelli, R.; et al. Multifocality in testicular germ cell tumor (TGCT): What is the significance of this finding? Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2014, 46, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, C.M.; Metcalfe, C.; Murray, N.; Black, P.C. Three primary testicular tumours: Trials and tribulations of testicular preservation. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2013, 7, E630–E633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Obiorah, I.E.; Kyrillos, A.; Ozdemirli, M. Synchronous Leydig Cell Tumor and Seminoma in the Ipsilateral Testis. Urol. Case Rep. 2018, 2018, 8747131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzimira, S.; Kandefer-Gola, M.; Kubiak-Nowak, D. A case report: Multiple primary testicular tumors in the dog. Acta Vet. Brno 2017, 86, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Grieco, V.; Riccardi, E.; Greppi, G.F.; Teruzzi, F.; Iermano, V.; Finazzi, M. Canine Testicular Tumours: A Study on 232 Dogs. J. Comp. Pathol. 2008, 138, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, H.H.L.; dos Santos, A.; Prante, A.L.; Lamego, E.C.; Tondo, L.A.S.; Flores, M.M.; Fighera, R.A.; Kommers, G.D. Testicular tumors in 190 dogs: Clinical, macroscopic and histopathological aspects. Pesqui. Vet. Bras. 2020, 40, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuali, E.; Forte, C.; Porcellato, I.; Brachelente, C.; Sforna, M.; Pavone, S.; Ranciati, S.; Morgante, R.; Crescio, I.M.; Ru, G.; et al. A five-year cohort study on testicular tumors from a population-based canine cancer registry in central Italy (Umbria). Prev. Vet. Med. 2020, 185, 105201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Švara, T.; Gombač, M.; Pogorevc, E.; Plavec, T.; Zrimšek, P.; Pogačnik, M. A retrospective study of canine testicular tumours in Slovenia. Slov. Vet. Res. 2014, 51, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxon, C.; Slack, J.; Bender, S.; Burns, H.; Turner, R. Multiple Sex Cord-stromal Tumors in a Standardbred Stallion Testis. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2023, 123, 104246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, A.T.; Chu, P.Y.; Yeh, L.S.; Lin, C.T.; Liu, C.H. A 12-year retrospective study of canine testicular tumors. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2009, 71, 919–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuberka, M.; Prządka, P.; Dzimira, S. Concurrent Leydig and Sertoli Cell Tumors Associated with Testicular Mycosis in a Dog: A Case Report and Literature Review. Pathogens 2025, 14, 752. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14080752

Kuberka M, Prządka P, Dzimira S. Concurrent Leydig and Sertoli Cell Tumors Associated with Testicular Mycosis in a Dog: A Case Report and Literature Review. Pathogens. 2025; 14(8):752. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14080752

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuberka, Mirosław, Przemysław Prządka, and Stanisław Dzimira. 2025. "Concurrent Leydig and Sertoli Cell Tumors Associated with Testicular Mycosis in a Dog: A Case Report and Literature Review" Pathogens 14, no. 8: 752. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14080752

APA StyleKuberka, M., Prządka, P., & Dzimira, S. (2025). Concurrent Leydig and Sertoli Cell Tumors Associated with Testicular Mycosis in a Dog: A Case Report and Literature Review. Pathogens, 14(8), 752. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14080752