Clinical, Immunological and Pathological Characteristics of Ischemic Dermatopathy in Dogs with Leishmaniosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Selection

2.2. Data and Sample Collection

2.3. Histopathology Evaluation

2.4. Leishmania Infantum Immunohistochemistry

2.5. IgG Immunohistochemistry

3. Results

3.1. Clinicopathological Data and Treatment Response

3.2. Histopathological Evaluation

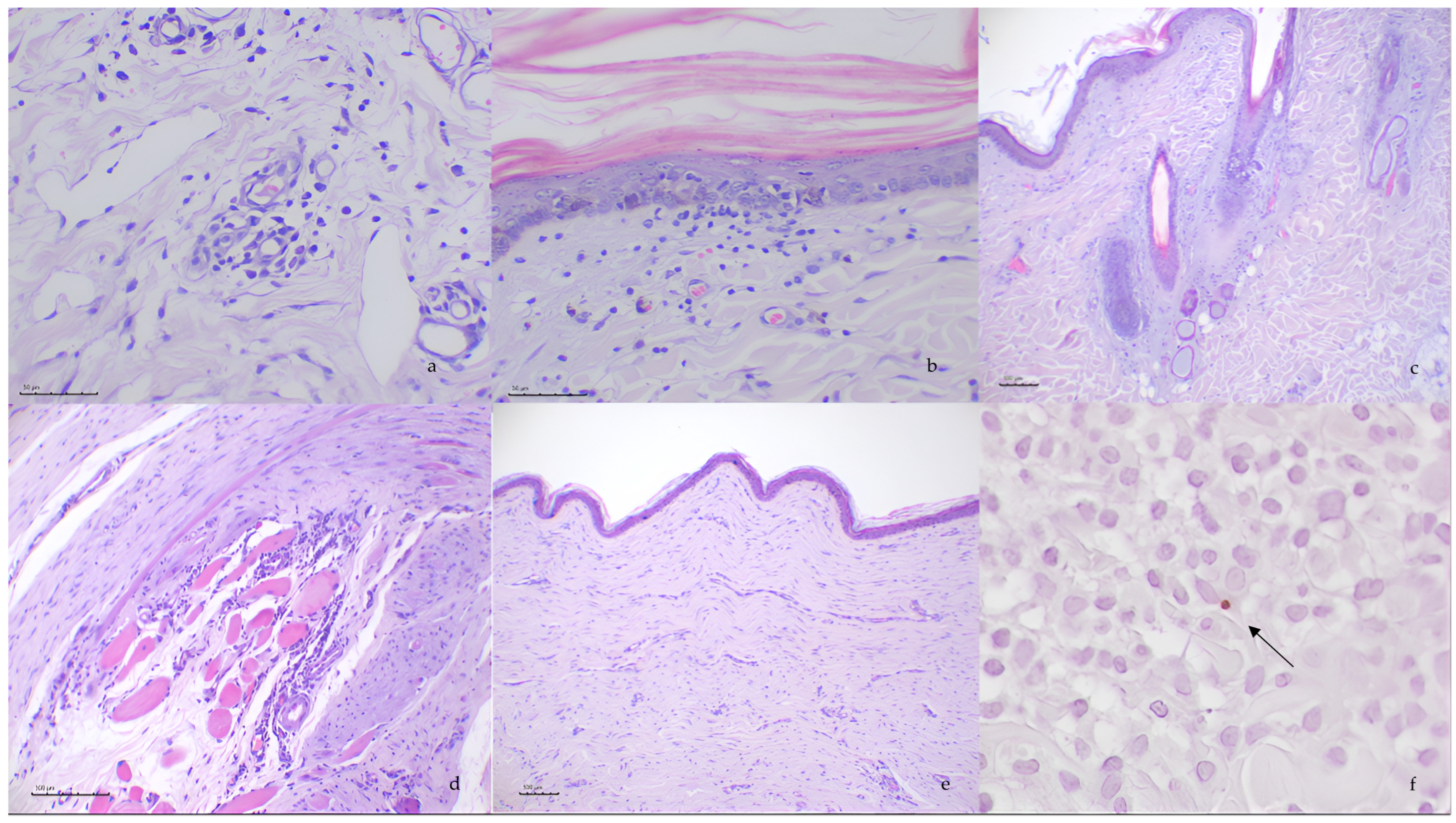

3.3. Histochemical and Immunohistochemical Evaluation

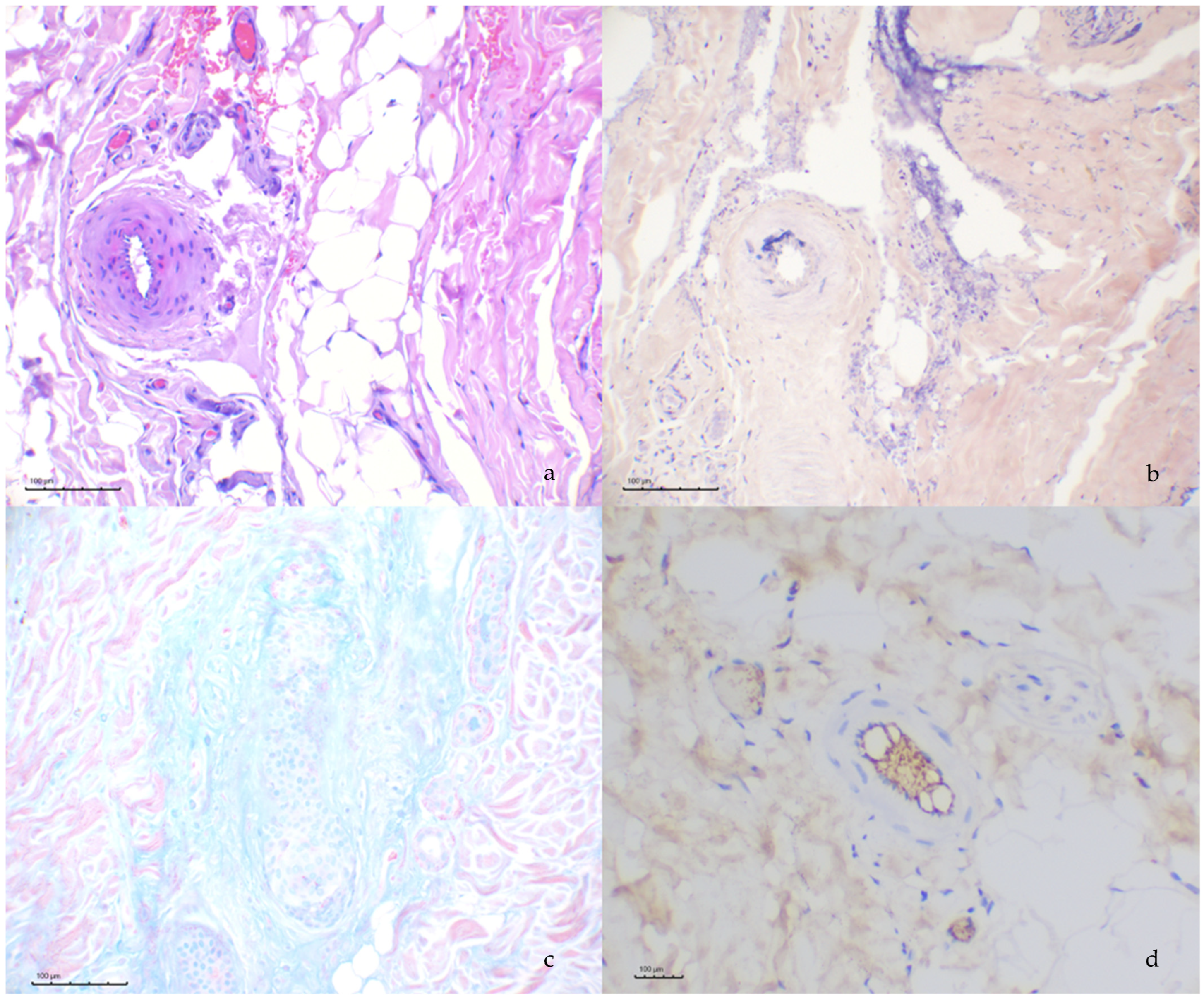

3.4. Leishmania spp. Immunohistochemistry

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ID | Ischemic dermatopathy. |

| CanL | Canine leishmaniosis. |

| CIC | Circulating immune complexes. |

| PAS | Periodic acid–Schiff. |

| PTAH | Phosphotungstic acid–haematoxylin. |

| UPC | Urinary protein creatinine ratio. |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin. |

References

- Morris, D.O. Ischemic dermatopathies. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2013, 43, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cousandier, G.; Scholten, A.D.; Scotton, G.; Stefanello, C. Juvenile-onset ischemic dermatopathy in a dog. Acta Sci. Vet. 2021, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.H.; Griffin, C.E.; Campbell, K.L. Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vitale; Gross; Magro. Vaccine-induced ischemic dermatopathy in the dog. Vet. Dermatol. 1999, 10, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, B.J.; Linder, K.E.; Olivry, T. The role of oclacitinib in the management of ischaemic dermatopathy in four dogs. Vet. Dermatol. 2019, 30, 201-e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saridomichelakis, M.N.; Koutinas, A.F. Cutaneous involvement in canine leishmaniosis due to Leishmania infantum (syn. L. chagasi). Vet. Dermatol. 2014, 25, 61-e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, L.; Rabanal, R.; Fondevila, D.; Ramos, J.A.; Domingo, M. Skin lesions in canine leishmaniasis. J. Small Anim. Pract. 1988, 29, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacheiro-Llaguno, C.; Parody, N.; Escutia, M.R.; Carnés, J. Role of circulating immune complexes in the pathogenesis of canine leishmaniasis: New players in vaccine development. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano-Gallego, L.; Miró, G.; Koutinas, A.; Cardoso, L.; Pennisi, M.G.; Ferrer, L.; Bourdeau, P.; Oliva, G.; Baneth, G. LeishVet guidelines for the practical management of canine leishmaniosis. Parasites Vectors 2011, 4, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano-Gallego, L.; Cardoso, L.; Pennisi, M.G.; Petersen, C.; Bourdeau, P.; Oliva, G.; Miró, G.; Ferrer, L.; Baneth, G. Diagnostic challenges in the era of canine Leishmania infantum vaccines. Trends Parasitol. 2017, 33, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteve, L.O.; Saz, S.V.; Hosein, S.; Solano-Gallego, L. Histopathological findings and detection of Toll-like receptor 2 in cutaneous lesions of canine leishmaniosis. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 209, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, T.L.; Ihrke, P.J.; Walder, E.J.; Verena, K.A. Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat: Clinical and Histopathologic Diagnosis, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Backel, K.A.; Bradley, C.W.; Cain, C.L.; Morris, D.O.; Goldschmidt, K.H.; Mauldin, E.A. Canine ischaemic dermat-opathy: A retrospective study of 177 cases (2005–2016). Vet. Dermatol. 2019, 30, 403-e122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargis, A.M.; Haupt, K.H.; Hegreberg, G.A.; Prieur, D.J.; Moore, M.P. Familial canine dermatomyositis. Initial characterization of the cutaneous and muscular lesions. Am. J. Pathol. 1984, 116, 234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hargis, A.M.; Prieur, D.J.; Haupt, K.H.; Collier, L.L.; Evermann, J.F.; Ladiges, W.C. Postmortem findings in four litters of dogs with familial canine dermatomyositis. Am. J. Pathol. 1986, 123, 480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gizzarelli, M.; Fiorentino, E.; Ben Fayala, N.E.H.; Montagnaro, S.; Torras, R.; Gradoni, L.; Oliva, G.; Manzillo, V.F. Assessment of circulating immune complexes during natural and experimental canine leishmaniasis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pumarola, M.; Brevik, L.; Badiola, J.; Vargas, A.; Domingo, M.; Ferrer, L. Canine leishmaniasis associated with systemic vasculitis in two dogs. J. Comp. Pathol. 1991, 105, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrent, E.; Leiva, M.; Segalés, J.; Franch, J.; Peña, T.; Cabrera, B.; Pastor, J. Myocarditis and generalised vasculitis associated with leishmaniosis in a dog. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2005, 46, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrus, S.; Day, M.J.; Waner, T.; Bark, H. Presence of immune-complexes, and absence of antinuclear antibodies, in sera of dogs naturally and experimentally infected with Ehrlichia canis. Vet. Microbiol. 2001, 83, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumura, K.; Kazuta, Y.; Endo, R.; Tanaka, K.; Inoue, T. Detection of circulating immune complexes in the sera of dogs infected with Dirofilaria immitis, by Clq-binding enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J. Helminthol. 1986, 60, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano-Gallego, L.; Di Filippo, L.; Ordeix, L.; Planellas, M.; Roura, X.; Altet, L.; Martínez-Orellana, P.; Montserrat, S. Early reduction of Leishmania infantum-specific antibodies and blood parasitemia during treatment in dogs with moderate or severe disease. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, H.; Kim, C.H.; Lee, Y.J. Bullous pemphigoid diagnosis: The role of routine formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded skin tissue immunochemistry. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García, N.; Cobos, À.; Solano-Gallego, L.; García, M.; Ordeix, L. Clinical, Immunological and Pathological Characteristics of Ischemic Dermatopathy in Dogs with Leishmaniosis. Pathogens 2025, 14, 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14030246

García N, Cobos À, Solano-Gallego L, García M, Ordeix L. Clinical, Immunological and Pathological Characteristics of Ischemic Dermatopathy in Dogs with Leishmaniosis. Pathogens. 2025; 14(3):246. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14030246

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía, Nuria, Àlex Cobos, Laia Solano-Gallego, Marina García, and Laura Ordeix. 2025. "Clinical, Immunological and Pathological Characteristics of Ischemic Dermatopathy in Dogs with Leishmaniosis" Pathogens 14, no. 3: 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14030246

APA StyleGarcía, N., Cobos, À., Solano-Gallego, L., García, M., & Ordeix, L. (2025). Clinical, Immunological and Pathological Characteristics of Ischemic Dermatopathy in Dogs with Leishmaniosis. Pathogens, 14(3), 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14030246